Abstract

Background

Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) survivors are at increased risk for the metabolic syndrome (MS). To establish the trajectory of development during active treatment, we followed patients longitudinally over the first year of maintenance therapy.

Procedure

In a prospective cohort of 34 pediatric ALL patients, followed over the first 12 months of ALL maintenance, we evaluated changes in body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, fasting insulin and glucose, lipids, homeostatic metabolic assessment (HOMA), leptin and adiponectin.

Results

Over the study time period, the median BMI z-score increased from 0.29 to 0.66 (p=0.001), median fasting insulin levels increased from 2.9 μU/ml to 3.1 μU/ml (p=0.023), and the proportion of patients with insulin resistance by HOMA (>3.15) increased from 3% to 24% (p=0.016). Median leptin increased from 2.5 ng/ml to 3.5 ng/ml (p=0.001), with levels correlated with BMI z-score. Median adiponectin level decreased from 18.0 μg/ml to 14.0 μg/ml (p=0.009), with levels inversely correlated to BMI z-score. No change in median total cholesterol and LDL levels was observed. Median triglycerides decreased (p<0.001) and there was a trend to increase in HDL (p=0.058). Blood pressure did not significantly change, although overall prevalence of systolic and diastolic hypertension was high (23.5% and 26.4%, respectively).

Conclusions

Following patients over the first year of ALL maintenance therapy demonstrated that components of the MS significantly worsen over time. Preventive interventions limiting increases in BMI and insulin resistance during maintenance therapy should be targeted during this time period to avoid long-term morbidity associated with the MS in long-term survivors.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, metabolic syndrome, obesity, insulin resistance, pediatrics, long-term side effects

Introduction

Cure rates for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) now exceed 85% (1). Coincident with improved survival are adverse long-term sequelae of treatment, including components of the metabolic syndrome (obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension), which are associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes (2-4). Obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance have been reported in long-term survivors (3, 5-8), leading investigators to better examine the onset and trajectory of these outcomes during active therapy, a time period that has been less well studied. Recent studies have demonstrated significant weight gain during the 2-3 year period of maintenance chemotherapy, when patients are exposed monthly to pulses of high-dose corticosteroids (9-11). It has also been reported that hypertension is prevalent during the maintenance period (9, 10). Chow et al. recently demonstrated the development of insulin resistance in pediatric patients undergoing maintenance therapy, as measured prior to and during or soon after a 5-day course of corticosteroids (12).

Despite the available retrospective and cross-sectional data regarding the metabolic syndrome, there is a paucity of prospective longitudinal data detailing the trajectory of metabolic abnormalities during active therapy, together with biologic correlates (3, 8, 12, 13). We therefore performed a prospective study to document the prevalence and trajectory of change in components of the metabolic syndrome over the first year of maintenance ALL therapy, together with an analysis of serum leptin and adiponectin levels. We hypothesized that dyslipidemia and insulin resistance, related to periodic pulses of corticosteroids, would persist and worsen over the course of this first year of maintenance and would correlate with BMI changes. Furthermore, as leptin and adiponectin are biomarkers associated with adiposity, we hypothesized that the trajectory of change in these biomarkers would also correlate with BMI and insulin resistance (14).

Methods

Study Design

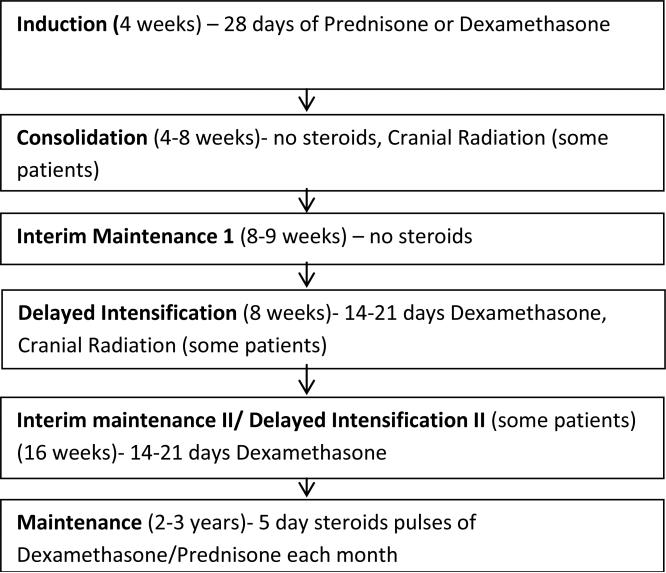

This was an observational cohort study, where data was captured retrospectively from induction through start of maintenance and then prospectively over the first year of maintenance. All patients with standard or high risk ALL between 2-20 years treated at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt who were within the first 3 months of maintenance therapy were eligible for study inclusion. After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board, an approach letter was mailed to all potential participants at the time of eligibility, followed by a consent conference conducted during their clinic visit. Thirty-six eligible patients who consecutively entered maintenance therapy were approached between November 2008 and February 2010, of whom 35 consented to participate. One enrolled participant died prior to the start of the study, resulting in a study population of 34 patients. All patients were treated on or according to Children's Oncology Group (COG) protocols. A basic schema for COG ALL trials is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schema for Children's Oncology Group Protocols (treated on or according to AALL0331 or AALL0232) with notation as to when corticosteroids and cranial radiation is given.

Data collection

From diagnosis until the start of maintenance chemotherapy, height, weight, and blood pressure measurements were abstracted retrospectively from medical records prior to each stage of therapy. These measurements were then obtained monthly and followed longitudinally throughout the first year of maintenance therapy to assess changes with ongoing therapeutic exposures, particularly corticosteroids. Height and weight were converted to BMI by [(weight in kilograms) / (height in centimeters)2], and the BMI was then converted to gender-specific z-scores using the Epi info nutrition module based on the CDC 2000 growth charts (ages 2-20 years) (15). For patients under 2 years of age, height for weight z-scores were used, and in patients over 20 years of age, gender-specific z-scores for a 20 year-old were used. Using established criteria, we defined overweight as BMI z-score ≥85th percentile and obese as ≥ 95th percentile (15). Both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were converted to z-scores using formulas developed by the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents (16). Hypertension was defined as 3 or more z-score measurements separated at least one month apart > 95th percentile adjusted for height, sex, and age (16). Parents completed a questionnaire that included self-report of parental height/weight as well as family history of myocardial infarction, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and insulin requirement in first- and second-degree relatives.

A fasting glucose, insulin, lipid profile, leptin, and adiponectin were drawn at the start of maintenance chemotherapy and at the conclusion of one year from study entry. Homeostasis Metabolic Assessment (HOMA) was calculated by [glucose (mg/dl) × insulin (μU/m1)/405], with levels >3.15 defined as insulin resistance (17).

Statistical considerations

Changes in continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon-signed rank test, and paired nominal variables were compared using McNemar's test. Spearman's correlations were used to test association between two continuous variables. Fisher's exact test was used to compare unpaired, nominal variables. All p values were 2-sided using <0.05 as the measure of significance. R 2.15 and SPSS version 20 were used for statistical analyses (18).

Results

Study population

The cohort of 34 participants was 64.7% male and 88.2% Caucasian, with a median age of 6 years (2-21 range) at the start of maintenance therapy, with baseline characteristics summarized in Table I. Twenty-one subjects (61.8%) had standard risk Pre-B cell ALL, 7 (20.6%) had high risk Pre-B cell ALL and 6 (17.6%) had T cell ALL. Nine subjects received cranial radiation (doses 12 – 18.6 Gy).

Table I.

Characteristics of the Cohort (N=34)

| Measurement | Baseline |

|---|---|

| Age at maintenance course 1# | 6 (3, 11) |

| Male gender* | 22 (64.7) |

| Race* | |

| White | 30 (88.2) |

| African American | 3 (8.8) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3.0) |

| ALL risk strataStandard risk versus high risk | |

| ALL* | |

| Standard risk | 21 (61.8) |

| High risk | 13 (38.2) |

| T cell versus Pre B ALL* | 6 (17.6) |

| Received cranial radiation* | 9 (26.5) |

| BMI z-score at cancer diagnosis# | 0.52 (−0.16, 1.47) |

| Maternal body mass index, n=31# | 26.6 (22.8, 31.7) |

| Paternal body mass index, n=31# | 28.8 (26.1, 31.2) |

| Family history of myocardial infarction, n=31* | 18 (58.1) |

| Family history of hypertension, n=30* | 27 (90.0) |

| Family history of hypercholesterolemia, n=25* | 16 (64.0) |

| Family history of diabetes, n=31* | 16 (51.6) |

| Family history of insulin dependence, n=29* | 6 (20.7) |

Median (quartiles)

N (%)

BMI changes

At diagnosis, the median BMI z-score for the cohort was elevated at 0.52 (quartiles −0.16, 1.47). The median z-score then increased at start of consolidation to 1.61 (quartiles 0.48, 1.98), then decreased to 0.29 (−0.27, 1.10) by the start of maintenance. The median z-score then gradually increased over the first year of maintenance to 0.66 (quartiles −0.25, 1.85, p=0.002). The change in BMI z-score paralleled the weight increases during the ALL treatment course. At diagnosis, 35.3% of the cohort was overweight and 17.6% obese, increasing to 64.7% overweight and 50.0% obese at the start of consolidation and subsequently decreasing to 29.4% overweight and 14.7% obese at the start of maintenance therapy. Weight then gradually increased, such that at the end of the first year of maintenance, 47.1% of the patients were overweight and 29.4% obese.

Parental BMI and Family History

As shown in Table I, parental BMI levels calculated from parental self-report of height and weight at study entry were elevated, with the median BMI of both parents meeting overweight criteria (maternal 26.6, paternal 28.8), and with the 75th quartile of the parents’ BMI being obese (maternal 31.7, paternal 31.2). Maternal and paternal BMI levels were not significantly correlated with each other (ρ=0.23 p=0.23). Neither maternal nor paternal BMI scores at study entry correlated with the subject's BMI z-score at cancer diagnosis (maternal ρ=0.30 p=0.10, paternal ρ=0.27 p=0.15) or at the end of one year of maintenance therapy (maternal ρ=−0.02 p=0.93, paternal ρ=0.20 p=0.29). BMI z-scores did not correlate with family history of cardiac risk factors.

Insulin resistance changes

Fasting insulin levels significantly increased over the first year of maintenance with the median increasing from 2.9 μU/ml to 3.1 μU/ml (p=0.023). Fasting glucose levels remained unchanged (p=0.63). At the start of maintenance therapy, only a single patient met criteria for insulin resistance by HOMA. In contrast, one year later, after 12 five-day cycles of corticosteroids, there were 8 such patients (p=0.023). HOMA levels at the start of maintenance were correlated with BMI z-score at the start of maintenance (ρ= 0.42 p=0.013) and again at one year, HOMA levels correlated with BMI z-score (ρ=0.54 p=0.001). HOMA did not correlate with a family history of diabetes or insulin dependence (Table II). No patients developed diabetes during the study period.

Table II.

Metabolic Changes during Maintenance Therapy for ALL(N=34)

| Measurement | Maintenance course 1 | Maintenance course 5 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI z-score# | 0.29 (−0.32, 1.17) | 0.66 (−0.28, 1.87) | 0.002 |

| Fasting Insulin (μU/ml)# | 2.9 (2.0, 5.1) | 3.1 (2.0, 12.7) | 0.023 |

| Fasting Glucose(mg/dl)# | 83.5 (75.8, 91.8) | 85.0 (78.0, 91.3) | 0.620 |

| HOMA^* | 0.63 (0.41, 1.10) | 0.58 (0.40, 2.94) | 0.066 |

| HOMA >3.15* | 1 (2.9) | 8 (23.5) | 0.016 |

| Leptin (ng/ml)# | 2.5 (1.1, 4.6) | 3.5 (1.3, 11.2) | 0.001 |

| Adiponectin (μg/ml)# | 18.0 (11.8, 24.3) | 14.0 (10.8, 19.3) | 0.009 |

Median (quartiles)

N (%)

Homeostasis Metabolic Assessment, $Insulin like growth factor 1 in patients over 5 years of age, deficiency >2 standard deviations below the median IGF1.

Biomarkers

Over the first year of maintenance therapy, median serum leptin levels increased from 2.5 ng/ml to 3.5 ng/ml (p=0.001). The magnitude of change was even greater in patients who were overweight at the start of maintenance, in whom median leptin levels increased from 4.0 ng/ml to 10.9 ng/ml (p=0.039). There was significant correlation between leptin levels and BMI z-scores obtained at the beginning (ρ=0.37, p=0.035) and end (ρ=0.60, p<0.001) of the study period. A similar relationship was noted between leptin and HOMA levels obtained at the beginning (ρ=0.36, p=0.039) and end (ρ=0.71, p=<0.001) of the study period. Median adiponectin levels notably decreased during maintenance from 18 μg/ml to 14 μg/ml (p=0.009). Adiponectin levels were not correlated with BMI z-score at the start of the study (ρ=−0.12 p=0.497). These became inversely correlated with BMI z-score by the end of the study (ρ=−0.43, p=0.012).

Dyslipidemia

Median total cholesterol and LDL levels did not change over the first year of maintenance therapy. Median triglycerides decreased from 83 mg/dl to 48 mg/dl (p<0.001), and there was a trend toward increased median HDL from 41 mg/dl to 45 mg/dl (p=0.059) over the first year of maintenance therapy. These improvements were most associated with treatment on high risk protocols, where triglycerides decreased from 176 mg/dl to 62 mg/dl (p<0.001) and HDL increased from 30 mg/dl to 45 mg/dl (p=0.002)]. Triglycerides at the start of maintenance therapy were significantly inversely correlated with HDL levels at the start of maintenance therapy (ρ=−0.62 p<0.001), and there was a trend towards inverse correlation at one year (ρ=−0.31 p=0.077). Neither HDL nor triglyceride levels at any time point correlated significantly with BMI z-score, HOMA, or a family history of hypercholesterolemia (Table III).

Table III.

Fasting Lipid Changes during Maintenance therapy for ALL (N=34)

| Measurement | Maintenance course 1 | Maintenance course 5 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl)# | 139.0 (121.5, 170.2) | 140.5 (109.0, 159.8) | 0.442 |

| LDL (mg/dl) (n=32)# | 76.5 (52.8, 88.8) | 81.0 (63.8, 100.0) | 0.963 |

| HDL (mg/dl)# | 40.5 (34.8, 55.3) | 45.0 (38.0, 53.5) | 0.058 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl)# | 83.0 (53.3, 136.8) | 47.5 (33.0, 74.3) | <0.001 |

| HDL (HR^) (mg/dl) (n=13)# | 30.0 (20.5, 40.5) | 45.0 (38.0, 60.0) | 0.005 |

| HDL (SR) (mg/dl) (n=21)# | 44.0 (39.5, 57.5) | 45.0 (39.5, 52.5) | 0.781 |

| Triglycerides (HR) (mg/dl) (n=13)# | 176.0 (97.5, 344.0) | 62.0 (34.0, 86.0) | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (sr) (mg/dl) (n=21# | 57.0 (44.5, 85.0) | 45.0 (33.0, 60.0) | 0.063 |

Median (quartiles)

*N (%)

Being treated on a high risk protocol (HR) versus a standard risk protocol (SR)

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure did not significantly worsen over the course of maintenance therapy; however, hypertension was prevalent. During the first year of maintenance therapy, the median average systolic blood pressure z-score was 0.46 (quartiles 0.16, 0.95) with 8/34 (23.5%) meeting criteria for systolic hypertension. The median diastolic average blood pressure was 0.36 (quartiles −0.00, 0.83) with 9/34 (26.4%) meeting criteria for diastolic hypertension. Systolic blood pressure z-score was correlated with diastolic blood pressure z-score at the start of maintenance (ρ=0.59 p<0.001), but not at the end of the study. Systolic blood pressure z-score was correlated with BMI z-score (ρ=0.357 p=0.049) at the end of one year of maintenance, however it was not significantly correlated at the start of maintenance (ρ=0.31 p=0.07) and diastolic blood pressure z-score was not correlated with BMI z-score at either time point. Blood pressure z-scores were not correlated with a family history of hypertension, HOMA, or fasting lipid parameters.

Discussion

Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome with correlative biomarkers has been reported in studies of ALL survivors, and a few studies have examined clinical features and associated biomarkers of the metabolic syndrome in ALL patients during active therapy (3, 5, 8, 12, 13) However, our study longitudinally followed patients for one year of maintenance therapy, documenting a worsening of metabolic changes in the same individuals (6, 8, 19).

Obesity in ALL patients is well described in long-term ALL survivors, with some studies demonstrating cranial radiation therapy as a significant risk factor (2, 20). However, obesity in survivors is also reported amongst those who did not receive cranial radiation (8). Several retrospective studies by our group and others have shown that excess weight gain occurs during therapy, with patients gaining weight during their first month of therapy, returning to baseline at the start of maintenance and then gaining weight again during maintenance therapy, with obesity continuing into the survivorship period (9-11). This pattern of weight gain during the first month and later during maintenance is likely related to corticosteroid exposure for 28 days continuously during induction therapy and recurrent 5-day pulses of corticosteroids monthly during maintenance therapy, where cumulative steroid dosing has been shown to be associated with weight gain (9, 10). Other factors may contribute to this weight gain, including prolonged sedentary behavior, lack of healthy eating habits and genetic predisposition. In our previous retrospective study as well as in the general obesity population, parental and child BMI are associated with one another, in this prospective study we were not able to demonstrate a relationship between parental BMI and the subjects’ BMI, likely due to the small sample size (10, 21).

Chow et al. recently reported that 13% of patients are insulin resistant at the initiation of a single maintenance cycle compared with 7% of patients who were off therapy. Immediately after a 5-day corticosteroid burst, greater than half of the patients were shown to have insulin resistance, suggesting that steroids likely play a role in acutely inducing insulin resistance (12). Our longitudinal study builds upon these data and further demonstrates that the prevalence of insulin resistance markedly increases from 2.9% at the start of maintenance to 22.9% one year into maintenance. Furthermore, in our cohort, both the baseline and follow-up glucose and insulin measurements were taken prior to the onset of the planned five-day corticosteroid exposure. Our cohort was younger (median age 6 years) than the cohort reported by Chow et al., who compared largely pre-pubertal / early pubertal patients (median age 9.4 years) with off-therapy largely post-pubertal patients (median age 15.8 years). As puberty is a natural state of insulin resistance, it is important to note that insulin resistance in our cohort is demonstrated prior to puberty. This increased insulin resistance is concerning, as these children are at increased risk for early onset type II diabetes, which has been observed in long-term survivors (3, 4).

Leptin and adiponectin are well-established biomarkers that strongly correlate with adiposity (14). As expected, leptin was positively correlated with both BMI z-score and HOMA during therapy, while adiponectin was inversely correlated with BMI z-score (14).

Dyslipidemia had a different pattern during therapy than the other metabolic syndrome components, as it was surprisingly common at the start of maintenance therapy but largely resolved during the maintenance courses that followed. This observation was most common in patients with high-risk disease and is likely related to PEG-asparaginase received during the preceding course of delayed intensification (22). However, more follow-up for dyslipidemia is required in the long-term survivorship period; after one year of maintenance therapy, the prevalence of low HDL was still significantly elevated at 29.4%.

As has been reported previously by our group, hypertension was highly prevalent at the start of maintenance therapy (10). This was persistent throughout the first year of maintenance and almost 25% of our cohort met criteria for systolic and diastolic hypertension during this time period. Chow et al. also showed a similar prevalence of hypertension (15.3%) in pediatric ALL patients at the end of therapy that persisted 2-3 years off therapy, indicating that hypertension continues to be a problem in this population (9).

In summary, children with ALL are at increased risk for metabolic abnormalities, which worsen over the course of maintenance therapy. Incorporating preventive strategies into the treatment regimen may prevent early development of these metabolic abnormalities that lead to cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Strategies that may provide benefit include nutrition and exercise interventions as well reduction in corticosteroid exposure, the latter of which is being tested in a Children's Oncology Group study. Our findings suggest that the first year of maintenance therapy should be targeted for preventive exercise and nutrition interventions, which will support the return to a healthy lifestyle. Several pilot studies have demonstrated feasibility of such an approach (23-25), but larger scale trials of efficacy are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NCRR/NIH; Grant number: 1 UL1RR024975.

References

- 1.Horner MJ RL, Krapcho M, et al. Seer cancer statistics review, 1975-2006. National Cancer Institue; Bethesda, MD: 2009. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/, based on Novemeber 2008 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2009 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garmey EG, Liu Q, Sklar CA, et al. Longitudinal changes in obesity and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4639–4645. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meacham LR, Chow EJ, Ness KK, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in adult survivors of pediatric cancer--a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:170–181. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberti KG, Zimmet PShaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janiszewski PM, Oeffinger KC, Church TS, et al. Abdominal obesity, liver fat, and muscle composition in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;92:3816–3821. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kourti M, Tragiannidis A, Makedou A, et al. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia after the completion of chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:499–501. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000181428.63552.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oeffinger KC. Are survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (all) at increased risk of cardiovascular disease? Pediatric blood & cancer. 2008;50:462–467. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21410. discussion 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trimis G, Moschovi M, Papassotiriou I, et al. Early indicators of dysmetabolic syndrome in young survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood as a target for preventing disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;29:309–314. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318059c249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow EJ, Pihoker C, Hunt K, et al. Obesity and hypertension among children after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2007;110:2313–2320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esbenshade AJ, Simmons JH, Koyama T, et al. Body mass index and blood pressure changes over the course of treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2011;56:372–378. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Withycombe JS, Post-White JE, Meza JL, et al. Weight patterns in children with higher risk all: A report from the children's oncology group (cog) for ccg 1961. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2009;53:1249–1254. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow EJ, Pihoker C, Friedman DL, et al. Glucocorticoids and insulin resistance in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pbc.24364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Sibley SD, et al. Metabolic syndrome and growth hormone deficiency in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006;107:1303–1312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan E, Chen S, Hong K, et al. Insulin, hs-crp, leptin, and adiponectin. An analysis of their relationship to the metabolic syndrome in an obese population with an elevated waist circumference. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6:64–73. doi: 10.1089/met.2007.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention 2000 growth charts for the united states: Improvements to the 1977 national center for health statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109:45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114:555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keskin M, Kurtoglu S, Kendirci M, et al. Homeostasis model assessment is more reliable than the fasting glucose/insulin ratio and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index for assessing insulin resistance among obese children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e500–503. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Team RC. R. A language and environment for statistical computing. Vol. 2012. v. software; Vienna, Austria: [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker KS, Chow ESteinberger J. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk in survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2012;47:619–625. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Obesity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1359–1365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, et al. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. The New England journal of medicine. 1997;337:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons SK, Skapek SX, Neufeld EJ, et al. Asparaginase-associated lipid abnormalities in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1997;89:1886–1895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moyer-Mileur LJ, Ransdell LBruggers CS. Fitness of children with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia during maintenance therapy: Response to a home-based exercise and nutrition program. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31:259–266. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181978fd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takken T, van der Torre P, Zwerink M, et al. Development, feasibility and efficacy of a community-based exercise training program in pediatric cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18:440–448. doi: 10.1002/pon.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh CH, Man Wai JP, Lin US, et al. A pilot study to examine the feasibility and effects of a home-based aerobic program on reducing fatigue in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:3–12. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181e4553c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]