Summary

This study compared nutritional intake during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent according to country of birth (US vs. Mexico) and, for Mexico-born women, according to number of years lived in the United States (≤ 5 years, 6–10 years ≥11 years). A 72-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to assess dietary intake in 474 pregnant Mexico-born immigrants and US-born Mexican-Americans. Mexico-born women had significantly higher intakes of calories (P = 0.02), fiber (P < 0.001), vitamin A (P < 0.001), vitamin C (P = 0.03), vitamin E (P < 0.01), folate (P < 0.01), calcium (P < 0.001) and zinc (P = 0.02) from their diets than US-born women. Intakes of all nutrients except vitamin C and zinc remained significantly higher in Mexico-born women when nutrients from both diet and vitamin supplements were considered. Among Mexico-born women, increasing years’ residence in the United States was associated with lower intake of calories (Ptrend < 0.01), fiber (Ptrend < 0.01), folate (Ptrend = 0.03), iron (Ptrend = 0.05) and zinc (Ptrend = 0.03), although only the trend for iron remained significant when vitamin supplement sources were included. A large percentage of women had inadequate intake of vitamin E (58%), folate (61%), iron (77%) and zinc (47%) from their diets during pregnancy and these rates were higher in US-born women than Mexico-born women.

Introduction

More than 7% of the United States population1 and 25% of the population of California2 are of Mexican descent. Because of high fertility and immigration rates, people of Mexican origin are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States. Mexican immigrants to the United States are more likely to live in poverty,3 have low educational attainment3–6 and have inadequate prenatal care5, 7, 8 than their US-born, Mexican-American counterparts. Despite these disadvantages, immigrant women born in Mexico have consistently been shown to have better pregnancy outcomes than Mexican-American women born in the US.3–12 US-born Mexican-Americans are more likely to deliver a low birthweight baby3, 6 or to experience preterm delivery5, 8, 11 than women born in Mexico.

The reasons for these differences in perinatal risk are largely unknown, but one possible explanation may be changes in diet that accompany acculturation in the US. No previous studies have examined how nutrient intake during pregnancy changes with acculturation among Mexican-origin women. However, four studies have examined dietary intake among non-pregnant women of Mexican descent, comparing immigrants born in Mexico with Mexican-Americans born in the US.13–16 In general, these studies found healthier diets among Mexico-born women than US-born women. Studies using 24-hour recall data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) found that women born in Mexico had significantly higher intakes of protein, carbohydrates, vitamin A, vitamin C, folate and calcium13 and were more likely to meet the US dietary guidelines or recommended daily allowance (RDA) for fat, saturated fat, fiber, vitamin C, folate, vitamin B6, calcium and magnesium than US-born Mexican-American women.14

Among Mexican immigrants, few studies have examined how nutrient intake changes with increasing years’ residence in the United States. Two previous studies17, 18 examined intake of different food groups among Mexican immigrants, but found conflicting results; one study found that intake of fruits and vegetables decreased17 while the other found that vegetable intake increased18 with time in the United States. Changes in dietary intake according to length of residence in the US would strengthen the hypothesis that the differences in diet between Mexico-born and US-born women are due to acculturative forces rather than an immigration-based selection bias.

We examined differences in dietary intake of US-born and Mexico-born pregnant women participating in the CHAMACOS (Center for Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas) study. We also analyzed dietary differences among Mexico-born women according to the number of years they had lived in the United States. This study gathered detailed information on regular food and vitamin supplement use during the second trimester of pregnancy using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) specifically adapted for this population.

Methods

Subjects and recruitment

The CHAMACOS study is a longitudinal birth cohort study of the effects of pesticides and other environmental exposures on the health of pregnant women and their children living in the Salinas Valley, an agricultural region of California. Details of the design and implementation of the CHAMACOS study have been published elsewhere.19, 20 Briefly, pregnant women entering prenatal care between October 1999 and October 2000 at a county hospital and five regional clinics were screened for eligibility and invited to participate in the study. Eligible women were 18 years or older, spoke English or Spanish, were less than 20 weeks gestation at enrollment, qualified for Medicaid (regardless of legal immigration status), and planned to deliver at the county hospital.

Of 1,130 eligible women, 601 (53.2%) agreed to participate in this multi-year study. Women who declined to participate were similar to study subjects with regard to age and parity, but were more likely to be English-speaking and born in the United States.

The present analysis was restricted to the 571 participants of Mexican descent. Seventy-eight additional participants were excluded because their dietary information was missing or incomplete, and 19 subjects were excluded because their reported food consumption on the FFQ fell outside the valid range (>20 solid food items/day). The final sample size for analysis was 474.

Definition of variables

Women were interviewed twice during pregnancy, at an average gestational age of 14 weeks (SD = 7) and 26 weeks (SD = 2). All interviews were conducted in English or Spanish by trained bilingual, bi-cultural interviewers. Mexican descent was determined at the first interview based on responses to questions about self-identified ethnicity, country of birth, and parents’ countries of birth. To gain information about acculturation level, each participant was asked about the language spoken in her home, her first spoken language, the number of years she had resided in the United States and the age she first came to the United States with the intention of living here. Because the vast majority of subjects (92%) were Spanish-speaking, it was not possible to use language as a measure of acculturation in the analysis. Instead, country of birth, years residing in the United States and age of moving to the United States were analyzed as proxies for acculturation. For women born in Mexico, years residing in the United States was analyzed as a categorical variable using the following categories: ≤ 5 years, 6 to 10 years, and ≥ 11 years. These categories were selected because previous studies have found changes in health behaviors and birth outcomes after just five years of residence in the United States.21

Data were gathered on demographic characteristics, such as maternal age, parity, marital status, education level and household income. Women were also asked about health-related behaviors, such as vitamin supplement use before and during pregnancy, self-reported smoking, drinking and drug use in each trimester of pregnancy and work history. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and height abstracted from the medical record. Pregnancy weight gain was determined by subtracting pre-pregnancy weight from the medical record delivery weight. Poverty level was calculated by dividing household income by the number of people supported by that income and comparing it to federal poverty thresholds.22

Dietary Assessment

At the second interview, women were asked about their food and nutrient intakes using a 72-item FFQ. Participants were asked how often they ate a particular food item in the previous three months and what the usual portion size was. Photographs of plates and bowls of foods were used to help participants estimate portion size. The FFQ was based on the Spanish-language Block 98 Questionnaire23–25 but was modified for this population. Focus groups were used to gather information on Mexican regional differences in foods and food names, and twenty-four hour recalls from local Mexican and Mexican-American women were analyzed to assess the appropriateness of the food list. Three foods were added (corn tortillas, smoothies made with milk and fruit (“licuados”), and avocados/guacamole) and the Spanish translation of the FFQ was altered to better reflect Mexican food names.

Information on food and supplement consumption was converted to average daily energy and nutrient intake using values from the USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference.26 We chose to examine intake of total calories, protein, folate, calcium, iron and zinc in this analysis because of their importance during pregnancy. Additionally, intake of fat, cholesterol, fiber, and vitamins A, C and E were analyzed. Nutrient intake from food alone and from food plus supplements were analyzed, as well as the prevalence of inadequate intake for each nutrient. Prevalence of inadequate intake was determined by calculating the proportion of the population below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) for pregnancy.27–29 The EAR is the nutrient intake estimated to meet the requirement of half the healthy individuals in a group and the proportion of the population below the EAR gives a good approximation of the prevalence of inadequacy.27 Because the EAR has not been established for calcium, the prevalence of inadequate intake could not be calculated for this nutrient.

Data analysis

Nutrient intakes were compared by country of birth (US-born versus Mexico-born) and, among Mexico-born women, by the number of years lived in the United States (≤ 5 years, 6 to 10 years, and ≥ 11 years). The distributions of all of the examined nutrients were skewed to the right because of very high intakes for a small number of subjects. For this reason, medians of nutrient intake were compared and non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon rank-sum test and a Wilcoxon-based test of trend30) were used to test for differences between groups. T-tests and chi-squared tests for linear trend were used for comparisons of inadequate intakes. Nutrients were examined both as the absolute level of intake and as nutrient densities. Nutrient densities were calculated by dividing daily nutrient intake by total daily calories to control for caloric intake. All analyses were conducted in STATA 8.0.31 Differences were considered statistically significant at alpha=0.05.

Results

Mexico-born versus US-born women

A comparison of demographic characteristics and health behaviors of Mexico-born women and US-born Mexican-American women is shown in Table 1. Women born in Mexico tended to be older (mean: 25.9 vs. 22.8 years) and more likely to be married than their US-born counterparts. There was no statistically significant difference in parity between the two groups. Mexico-born women tended to have lower pre-pregnancy weight (mean: 142.9 vs. 155.3 lbs) and lower weight gain during pregnancy (mean: 29.1 vs. 34.1 lbs). Because Mexico-born women were also of shorter stature, no significant differences were seen in pre-pregnancy BMI. Mexico-born women were less educated, more likely to be living below poverty level and more likely to be working in agriculture. As expected, more Mexico-born women were Spanish-speaking, although almost half of the US-born women spoke mostly Spanish at home. Mexico-born women were significantly less likely to smoke or to use alcohol or drugs during pregnancy than US-born women, although use of these substances was very low in both groups.

Table 1.

Demographic comparison of Mexico-born and US-born women. CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000–2001.

| Mexico-born (N = 425) N (%) |

US-born (N = 49) N (%) |

p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | |||

| 18–24 | 192 (45.2) | 35 (71.4) | |

| 25–29 | 134 (31.5) | 11 (22.5) | |

| 30–34 | 68 (16.0) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 35+ | 31 (7.3) | 2 (4.1) | <0.01 |

| Parity: | |||

| 0 | 146 (34.4) | 21 (42.9) | |

| 1 | 124 (29.2) | 15 (30.6) | |

| 2+ | 155 (36.5) | 13 (26.5) | 0.34 |

| Marital status: | |||

| Married/Living as married | 355 (83.7) | 31 (63.3) | |

| Single | 69 (16.3) | 18 (36.7) | <0.01 |

| Education: | |||

| Less than 6th grade | 218 (51.3) | 1 (2.0) | |

| 7th through 12th grade | 151 (35.5) | 23 (46.9) | |

| Completed high school | 56 (13.2) | 25 (51.0) | <0.01 |

| Family income: | |||

| At or below poverty level | 260 (65.2) | 20 (42.6) | |

| Poverty level - 200% poverty level | 129 (32.3) | 25 (53.2) | |

| Above 200% poverty level | 10 (2.5) | 2 (4.3) | 0.01 |

| Years residing in US: | |||

| ≤ 5 | 255 (60.0) | 2 (4.1) | |

| 6–10 | 106 (24.9) | 1 (2.0) | |

| ≥ 11 | 64 (15.1) | 46 (93.9) | <0.01 |

| Language spoken at home: | |||

| Mostly Spanish | 409 (96.9) | 24 (49.0) | |

| Both Spanish and English | 9 (2.1) | 11 (22.5) | |

| Mostly English | 1 (0.2) | 14 (28.6) | |

| Mexican Indian Languages | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | <0.01 |

| Work status during pregnancy: | |||

| Worked in agriculture | 179 (42.2) | 4 (8.2) | |

| Other work | 62 (14.6) | 27 (55.1) | |

| Did not work | 184 (43.3) | 18 (36.7) | <0.01 |

| Smoked during pregnancy: | |||

| No | 410 (97.2) | 42 (85.7) | |

| Yes | 12 (2.8) | 7 (14.3) | <0.01 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy: | |||

| None | 359 (84.9) | 33 (67.4) | |

| Less than 1 serving per week | 61 (14.4) | 15 (30.6) | |

| One serving per week or more | 3 (0.7) | 1 (2.0) | 0.02 |

| Used drugs during pregnancy: | |||

| No | 421 (99.5) | 47 (95.9) | |

| Yes | 2 (0.5) | 2 (4.1) | <0.01 |

| Pre-pregnancy Body Mass Index (kg/m3): | |||

| < 18.5 | 2 (0.5) | 0 0.0 | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 167 (40.2) | 17 (35.4) | |

| 25–29.9 | 157 (37.8) | 18 (37.5) | |

| ≥ 30 | 89 (21.5) | 13 (27.1) | 0.78 |

| Taking vitamin supplements in 3 months before pregnancy: | |||

| No | 349 (83.9) | 39 (79.6) | |

| Yes | 67 (16.1) | 10 (20.4) | 0.44 |

| Taking vitamin supplements in 2nd trimester of pregnancy: | |||

| No | 32 (7.7) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Yes | 382 (92.3) | 44 (89.8) | 0.56 |

Chi-square test

No differences were seen between Mexico-born and US-born women in vitamin supplement use before or during pregnancy. Overall, only 17% of women reported using vitamin supplements near the time of conception, but approximately 90% of women were taking supplements by the second trimester of pregnancy. All women had access to free prenatal vitamins through prenatal care and/or Medicaid.

Table 2 shows the differences in dietary intake during pregnancy between Mexico-born and US-born women. Mexico-born women consumed more overall calories than US-born women, despite the fact that they had lower pre-pregnancy weights and lower pregnancy weight gains. Dietary composition in terms of percentage of calories from protein, fat and saturated fat was similar in Mexico-born and US-born women. Intake of cholesterol did not vary between the two groups, but Mexico-born women were found to consume considerably more fiber than US-born women. This finding persisted when fiber was analyzed as a nutrient density. For both groups, the median level of intake for calories and fiber was below the recommended level during pregnancy and the percentage of fat was above the recommended level.32

Table 2.

Comparison of medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) of daily intake during pregnancy for select macronutrients, micronutrients and food groups among Mexico-born and US-born women. CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000–2001.

| Daily intake

|

p-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico-born (N = 425) Median (IQR) |

US-born (N = 49) Median (IQR) |

||

| Macronutrients | |||

| Energy (kcal) | 2285.1 (1867.2, 2900.8) | 2227.4 (1492.6, 2570.8) | 0.02 |

| Protein (% of calories) | 12.3 (11.1, 13.7) | 12.6 (10.6, 13.9) | 0.95 |

| Fat (% of calories) | 38.2 (34.5, 41.9) | 38.3 (34.5, 41.3) | 0.71 |

| Saturated Fat (% of calories) | 11.8 (10.3, 13.3) | 12.4 (10.7, 13.5) | 0.39 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 257.9 (184.2, 342.0) | 225.6 (146.5, 300.7) | 0.11 |

| Fiber (g) | 20.4 (14.9, 27.4) | 16.3 (12.2, 21.5) | <0.001 |

| Micronutrients | |||

| From food: | |||

| Vit A (μg RAE) | 1361.4 (967.7, 1842.2) | 1034.7 (764.3, 1469.9) | <0.001 |

| Vit C (mg) | 167.9 (113.2, 256.7) | 148.6 (94.1, 206.2) | 0.03 |

| Vit E (mg α-TE) | 11.1 (8.6, 14.2) | 9.1 (6.6, 13.4) | <0.01 |

| Folate (μg) | 475.5 (374.7, 616.8) | 424.1 (330.0, 485.5) | <0.01 |

| Iron (mg) | 15.8 (11.3, 21.5) | 14.3 (11.6, 21.0) | 0.60 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1177.4 (891.1, 1502.7) | 914.6 (612.8, 1289.4) | <0.001 |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.8 (7.6, 12.4) | 8.8 (6.5, 11.0) | 0.02 |

| From food and supplements: | |||

| Vit A (μg RAE) | 2441.7 (2048.2, 2939.2) | 2156.5 (1779.0, 2667.1) | <0.01 |

| Vit C (mg) | 258.9 (195.8, 354.3) | 218.9 (186.2, 299.1) | 0.07 |

| Vit E (mg α-TE) | 21.3 (17.7, 24.5) | 19.5 (16.2, 23.4) | 0.03 |

| Folate (μg) | 1240 (1086.6, 1411.7) | 1186 (1076.8, 1261.5) | 0.04 |

| Iron (mg) | 46.8 (37.4, 102.4) | 42.2 (38.0, 92.5) | 0.31 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1402.2 (1063.1, 1754.2) | 1156.1 (818.5, 1527.1) | <0.01 |

| Zinc (mg) | 33.8 (30.5, 36.9) | 33.0 (29.5, 35.5) | 0.15 |

| Food Group Servings | |||

| Fruits | 2.8 (1.8, 3.9) | 2.5 (1.3, 3.1) | 0.02 |

| Vegetables | 2.3 (1.4, 3.6) | 2.1 (1.6, 3.6) | 0.85 |

| Grains | 4.6 (3.4, 6.0) | 4.1 (3.2, 5.0) | 0.05 |

| Dairy Products | 2.5 (1.6, 3.3) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) | <0.01 |

| Meats | 2.1 (1.4, 2.8) | 1.9 (1.2, 2.4) | 0.10 |

Wilcoxon rank sum test

When intake of micronutrients from food alone was analyzed, the diets of Mexico-born women contained more vitamins A, C and E, folate, calcium and zinc than those of US-born women. No differences were seen in dietary intake of iron. When supplements were included in the analysis, Mexico-born women continued to consume larger amounts of vitamin A, vitamin E, folate and calcium than US-born women.

Nutrient densities were also compared between the two groups to control for increased caloric intake among Mexico-born women. Using nutrient densities, vitamin A and calcium intake from food remained significantly higher among Mexico-born women, but no differences were seen with nutrient densities from food plus supplements (not shown).

An analysis of food groups found that Mexico-born women consumed significantly more fruits, grains and dairy products per day than US-born women, which is consistent with the finding of increased vitamins and calcium in this group. No differences were found between the two groups in consumption of vegetables or meats.

Table 3 shows the percentage of women with inadequate intake of selected nutrients, comparing Mexico-born and US-born women. Overall, intake of vitamin A and vitamin C was good, with more than 85% of women in both groups achieving adequate intake from their food alone and more than 98% achieving adequate intake from food and supplements combined. Although the rates of inadequacy were low, US-born women were significantly more likely to have inadequate intake of vitamin A from their diets than Mexico-born women.

Table 3.

Prevalence of inadequate intakes (intake below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR)) for select nutrients among Mexico-born and US-born pregnant women. CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000–2001.

| EAR during pregnancy | Inadequate intake

|

p-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico-born (N = 425) N (%) |

US-born (N = 49) N (%) |

|||

| From food: | ||||

| Vit A (μg RAE) | 550 | 15 (3.5) | 7 (14.3) | <0.01 |

| Vit C (mg) | 70 | 26 (6.1) | 4 (8.2) | 0.58 |

| Vit E (mg α-TE) | 12 | 240 (56.5) | 35 (71.4) | 0.05 |

| Folate (μg) | 520 | 249 (58.6) | 39 (79.6) | <0.01 |

| Iron (mg) | 22 | 326 (76.7) | 38 (77.6) | 0.89 |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.5 | 194 (45.7) | 29 (59.2) | 0.07 |

| From food and supplements: | ||||

| Vit A (μg RAE) | 550 | 4 (0.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0.48 |

| Vit C (mg) | 70 | 4 (0.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0.48 |

| Vit E (mg α-TE) | 12 | 38 (8.9) | 4 (8.2) | 0.86 |

| Folate (μg) | 520 | 30 (7.1) | 5 (10.2) | 0.42 |

| Iron (mg) | 22 | 41 (9.7) | 5 (10.2) | 0.91 |

| Zinc (mg) | 9.5 | 20 (4.7) | 3 (6.1) | 0.66 |

Chi-square test

A large proportion of women in both groups had inadequate intake of vitamin E, folate, iron and zinc from their diets alone. Inadequate intake of iron was particularly common, occurring in 77% of women, and did not vary by country of birth. Inadequate intake of vitamin E, folate and zinc was high in both groups, but was significantly higher in US-born women than Mexico-born women (vitamin E inadequacy: 71% vs. 57%; folate inadequacy: 80% vs. 56%; zinc inadequacy: 59% vs. 46%). Because prenatal vitamin supplement use was very high in this population, almost all women were able to meet the EAR for selected micronutrients when food and supplement sources were combined. When supplement use was included, no differences were seen in inadequate intake of any micronutrients comparing US-born and Mexico-born women.

Time residing in the United States

To determine whether dietary differences exist among Mexico-born women according to the number of years residing in the United States, we also examined nutrient intake by categories of years lived in the United States (≤ 5 years, 6 to 10 years, and > 11 years). No differences were seen in vitamin intake according to number of years in the US, but significant increases in pre-pregnancy BMI were seen with increasing time in the United States. The mean BMI for women residing in the US for 5 years or less was 25.3 kg/m3, for 6 to 10 years was 28.2 kg/m3, and for 11 years or more was 29.4 kg/m3 (ptrend < 0.001). This trend persisted after adjusting for maternal age, parity, education and poverty level.

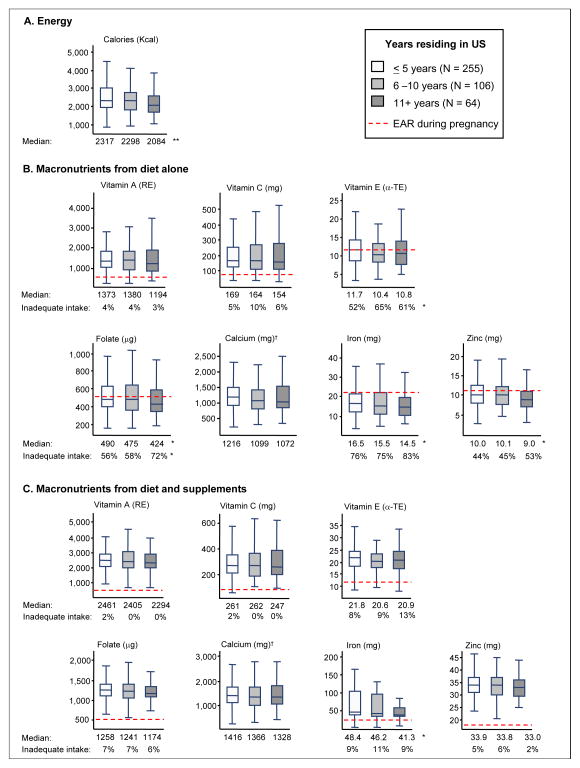

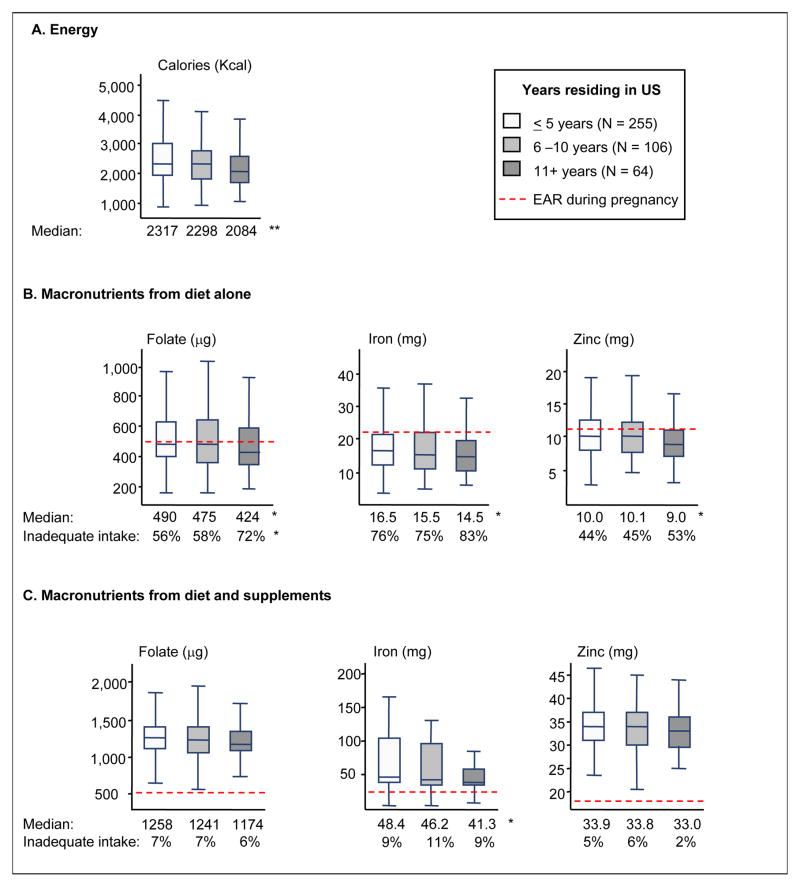

Figure 1 shows significant trends in decreasing intake of calories with increased time in the United States. No significant trends were seen for dietary composition in terms of percent of calories from protein, fat or saturated fat, but significant decreases in fiber were seen with increased time in the US (not shown). Intake of folate, iron and zinc from food also showed a trend of decreasing intake with increased time in the US, but only the decrease in iron remained significant when food and supplements were combined. No significant trends were seen for intake of vitamin A, vitamin C or vitamin E.

Figure 1.

Medians and interquartile ranges of daily nutrient intake and prevalence of inadequate intake (intake below the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR)) for select nutrients during pregnancy according to years residing in the United States (Mexico-born women only). CHAMACOS Study, Salinas Valley, California, 2000–2001.

* p-value for trend ≤ 0.05 ** p-value for trend ≤ 0.01

To assess whether the decreases in folate, iron and zinc with time in the US were due to changes in dietary composition or to decreased caloric intake, we also compared nutrient densities by number of years lived in the United States. When nutrient densities were used, no differences were seen in micronutrient intake (not shown), suggesting that the observed decreases in micronutrient intake were largely a function of decreased overall caloric intake.

The percentage of women with inadequate intake of select nutrients is also shown in Figure 1. Significant trends of increasing percentages of women with inadequate intake of vitamin E and folate were seen with increasing years in the US. The percentage of women with inadequate intakes of other micronutrients did not vary by time residing in the United States. Because supplement use was high in all three groups, inadequate intake was uncommon when supplement use was included in the analysis. No trends were seen with time residing in the United States when supplement use was considered.

Discussion

This study found that pregnant women born in Mexico had diets higher in several micronutrients (vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin E, folate, calcium and zinc) and that were more likely to meet current health recommendations than pregnant Mexican-American women, despite the fact that Mexico-born women were more likely to live in poverty and to have very low educational attainment. Additionally, we found that, among women born in Mexico, dietary intake of folate, iron and zinc was higher among women who had lived fewer years in the United States.

The results of this study were similar to those found in studies of non-pregnant populations. Previous studies have also found lower intake of vitamin A, vitamin C, folate, calcium and zinc among US-born Mexican-Americans.13–16 Our study found no difference in iron intake by country of birth, although other studies have found increased iron intake among Mexico-born women.13, 15 Levels of intake in this study were similar to the other studies that used an FFQ to assess intake.15, 16 It should be noted that food frequency questionnaires yield point estimates of intake that, while useful for comparison purposes, are not exact reflections of intake. However, the point estimates from the FFQ used in this study have been found to correlate well with multiple food diaries.24, 25

This study found that caloric intake was higher among Mexico-born women than US-born women and, among Mexico-born women, was higher among women who had lived in the US for a shorter time. After controlling for caloric intake, few differences were seen in nutrient intake between groups. However, micronutrient recommendations during pregnancy are based on absolute levels of intake and absolute levels of intake, rather than nutrient densities, may be more relevant to pregnancy outcome. Interestingly, the group with the highest caloric intake, Mexico-born women, and recent immigrants in particular, had the lowest pre-pregnancy weights and pregnancy weight gains. Although physical activity was not measured in this study, it is possible that this group was more physically active.

One limitation of this study is that we were not able to take serial measurements over time to determine how women’s diets changed longitudinally with increasing years in the US. However, we were able to compare Mexico-born women in a fairly homogenous, low-income population who had lived in the US for a variety of years. An additional limitation was that US-born and English-speaking women were more likely to decline to participate in the study, resulting in a small sample of highly acculturated women. However, even in this population with relatively low levels of acculturation, we saw differences in diet according to number of years living in the United States.

This study was conducted in a prenatal care population with very high prenatal vitamin use. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to all pregnant Mexican immigrant and Mexican-American women. Studies have shown that many Mexican-origin women receive late or inadequate prenatal care,33 and it is likely that use of vitamin supplement use during pregnancy was higher in our study than in the general population. As a result, the findings from food alone may be more relevant to the general population. However, most of the differences in dietary intake between US-born and Mexico-born women persisted regardless of whether vitamin supplement use was considered.

The findings of this study may help explain the lower prevalence of low birthweight and preterm delivery among Mexico-born women. Several authors have noted that Mexico-born women have lower rates of low birthweight than their US-born counterparts, despite being more likely to have many pregnancy risk factors, such as poverty, low education and limited access to prenatal care.34, 35 One current explanation is that traditional beliefs and behaviors associated with Mexican culture, including a healthier diet, may be protective during pregnancy.36 Studies have indicated that higher intake of folate37–39, zinc40, 41 and iron42 during pregnancy may be associated with increased birthweight. In our study, all three of these nutrients were lower among women who had lived longer in the United States. Future analyses will examine whether diet during pregnancy affects birth outcome in this population and can help explain the apparent paradox.

In summary, we found that Mexico-born women had healthier diets than their US-born counterparts. We also found that, among Mexico-born women, women who had lived in the US longer had diets lower in some important micronutrients than more recent immigrants. These data contribute to the growing evidence for the negative effects of acculturation on the health of pregnancy in Mexican-origin women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant Numbers R876709 from EPA and ES09605 from NIEHS, with additional funding provided by UC Berkeley’s Center for Latino Policy Research and Vice Chancellor for Research Fund. The authors would like to thank Erin Weltzien and Ellie Gladstone for assistance with preparing this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge all the dedicated CHAMACOS staff, students and community partners. Most of all, we thank the CHAMACOS participants and their families, without whom this study would not be possible.

References

- 1.Guzman B. The Hispanic Population: Census 2000 Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. Report No.: C2KBR/01-3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Census Bureau. Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 Census of Population and Housing: California. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guendelman S, Gould JB, Hudes M, Eskenazi B. Generational differences in perinatal health among the Mexican American population: findings from HHANES 1982–84. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(Suppl 5):61–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zambrana RE, Scrimshaw SC, Collins N, Dunkel-Schetter C. Prenatal health behaviors and psychosocial risk factors in pregnant women of Mexican origin: the role of acculturation. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(6):1022–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.6.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ventura SJ, Taffel SM. Childbearing characteristics of U.S- and foreign-born Hispanic mothers. Public Health Reports. 1985;100(6):647–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins JW, Jr, Shay DK. Prevalence of low birth weight among Hispanic infants with United States-born and foreign-born mothers: the effect of urban poverty [see comments] American Journal of Epidemiology. 1994;139(2):184–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams RL, Binkin NJ, Clingman EJ. Pregnancy outcomes among Spanish-surname women in California. American Journal of Public Health. 1986;76(4):387–91. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.4.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh GK, Yu SM. Adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences between US- and foreign-born women in major US racial and ethnic groups. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(6):837–43. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.6.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.English PB, Kharrazi M, Guendelman S. Pregnancy outcomes and risk factors in Mexican Americans: the effect of language use and mother’s birthplace. Ethnicity and Disease. 1997;7(3):229–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuentes-Afflick E, Lurie P. Low birth weight and Latino ethnicity. Examining the epidemiologic paradox. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1997;151(7):665–74. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170440027005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crump C, Lipsky S, Mueller BA. Adverse birth outcomes among Mexican-Americans: are US-born women at greater risk than Mexico-born women? Ethnicity and Health. 1999;4(1–2):29–34. doi: 10.1080/13557859998164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scribner R, Dwyer JH. Acculturation and low birthweight among Latinos in the Hispanic HANES. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79(9):1263–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guendelman S, Abrams B. Dietary intake among Mexican-American women: generational differences and a comparison with white non-Hispanic women. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(1):20–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon LB, Sundquist J, Winkleby M. Differences in energy, nutrient, and food intakes in a US sample of Mexican-American women and men: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152(6):548–57. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaffer DM, Velie EM, Shaw GM, Todoroff KP. Energy and nutrient intakes and health practices of Latinas and white non-Latinas in the 3 months before pregnancy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1998;98(8):876–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monroe KR, Hankin JH, Pike MC, Henderson BE, Stram DO, Park S, et al. Correlation of dietary intake and colorectal cancer incidence among Mexican-American migrants: the multiethnic cohort study. Nutr Cancer. 2003;45(2):133–47. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4502_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chavez N, Sha L, Persky V, Langenberg P, Pestano-Binghay E. Effect of length of US residence on food group intake in Mexican and Puerto Rican women. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1994;26(2):79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guendelman S, Siega-Riz A. Infant feeding practices and maternal dietary intake among Latino immigrants in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2002;4(3):137–146. doi: 10.1023/A:1015698817387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eskenazi E, Bradman A, Gladstone E, Jaramillo S, Birch K, Holland N. CHAMACOS, a longitudinal birth cohort study: Lessons from the fields. Journal of Children’s Health. 2003;1:3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eskenazi B, Harley K, Bradman A. The association of in utero organophosphate pesticide exposure and fetal growth and length of gestation. Environ Health Persp. 2004 doi: 10.1289/ehp.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guendelman S, English PB. Effect of United States residence on birth outcomes among Mexican immigrants: an exploratory study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;142(9 Suppl):S30–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/142.supplement_9.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. 2000. Poverty Thresholds 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Block G, DiSogra C. Final Report. Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; WIC Dietary Assessment Validation Study. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block G, Woods M, Potosky A, Clifford C. Validation of a self-administered diet history questionnaire using multiple diet records. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(12):1327–35. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90099-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Block G, Thompson FE, Hartman AM, Larkin FA, Guire KE. Comparison of two dietary questionnaires validated against multiple dietary records collected during a 1-year period. J Am Diet Assoc. 1992;92(6):686–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.USDA. Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Bethesda, MD: Human Nutrition Information Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Applications in dietary assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy SP, Poos MI. Dietary Reference Intakes: summary of applications in dietary assessment. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6A):843–9. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy SP, Barr SI, Poos MI. Using the new dietary reference intakes to assess diets: a map to the maze. Nutr Rev. 2002;60(9):267–75. doi: 10.1301/002966402320387189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. Stata Reference Manual, Release 7. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frisbie WP, Biegler M, de Turk P, Forbes D, Pullum SG. Racial and ethnic differences in determinants of intrauterine growth retardation and other compromised birth outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(12):1977–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scribner RA. Infant mortality among Hispanics: the epidemiological paradox [letter; comment] Jama. 1991;265(16):2065–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de la Rosa IA. Perinatal outcomes among Mexican Americans: a review of an epidemiological paradox. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(4):480–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scribner R. Paradox as paradigm--the health outcomes of Mexican Americans [editorial; comment] [see comments] American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(3):303–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Schall JI, Khoo CS, Fischer RL. Dietary and serum folate: their influence on the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63(4):520–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura T, Goldenberg RL, Freeberg LE, Cliver SP, Cutter GR, Hoffman HJ. Maternal serum folate and zinc concentrations and their relationships to pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56(2):365–70. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rondo PH, Abbott R, Rodrigues LC, Tomkins AM. Vitamin A, folate, and iron concentrations in cord and maternal blood of intra-uterine growth retarded and appropriate birth weight babies. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1995;49(6):391–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldenberg RL, Tamura T, Neggers Y, Copper RL, Johnston KE, DuBard MB, et al. The effect of zinc supplementation on pregnancy outcome. Jama. 1995;274(6):463–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530060037030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholl TO, Hediger ML, Schall JI, Fischer RL, Khoo CS. Low zinc intake during pregnancy: its association with preterm and very preterm delivery. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(10):1115–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen LH. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5 Suppl):1280S–4S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1280s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]