Abstract

Building on the Stereotype Content Model, this paper introduces and tests the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework. A growing body of research suggests that consumers have relationships with brands that resemble relations between people. We propose that consumers perceive brands in the same way they perceive people. This approach allows us to explore how social perception theories and processes can predict brand purchase interest and loyalty. Brands as Intentional Agents Framework is based on a well-established social perception approach: the Stereotype Content Model. Two studies support the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework prediction that consumers assess a brand’s perceived intentions and ability and that these perceptions elicit distinct emotions and drive differential brand behaviors. The research shows that human social interaction relationships translate to consumer-brand interactions in ways that are useful to inform brand positioning and brand communications.

Arguably, people relate to brands in many ways similarly to how they relate to people (Fournier; 2009). Inspired by the introduction of human relationship theory and thinking into the branding literature and marketing practice (Fournier,1998; 2009; Mark & Pearson, 2001), we propose that understanding how consumers perceive and relate to brands can profit from models of social perception developed in social psychology and specifically from the well established Stereotype Content Model (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007). Research on brand perception has shown that consumers not only care about a brand’s features and benefits but also about a relational aspect of brand perception (Aaker, Fournier, & Brasel, 2004; Fournier, 2009; see MacInnis et al., 2009, for a review) as well as an emotional part (Ahuvia, 2005; Noel, Merunka, & Valette-Florence, 2010; Thomson, MacInnis, & Park, 2005). So not only does a brand’s delivery, its perceived ability or competence, matter but also its perceived intentions or warmth affect how the way consumers perceive, feel, and behave toward that brand. This article presents a well-established social perception model, the Stereotype Content Model, and explores its usefulness in predicting how consumers perceive, feel, and behave toward brands.

As we will review, different elements composing the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework (BIAF) already demonstrably apply both to social and brand perception. The added value of the proposed BIAF is that it integrates the two dimensions (intentions and ability) and the three aspects of brand perception, from evaluative dimensions to emotional reaction to behavior, and thus it provides a more comprehensive model building on the strengths of each dimensions and type of analysis taken separately. We will start by reviewing the Stereotype Content model, the social perception model that serves as the template for our BIAF. Then we will present existing evidence for treating brand perception as similar to social perception before introducing the BIAF itself and testing it.

The Stereotype Content Model

Over the last decade, social psychologists (Asbrock, 2010; Asbrock, Nieuwoudt, Duckitt, & Sibley, 2011; Caprariello, Cuddy, & Fiske, 2009; Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2007; Cuddy, Fiske, Kwan, Glick, Demoulin, Leyens, Bond, et al., 2009; Fiske et al., 2002; Russell & Fiske, 2008) have proposed, tested, and validated a model of social perception called the Stereotype Content Model. The Stereotype Content Model maps out how people perceive social groups on the two dimensions of social perception: Warmth and Competence. The Stereotype Content Model is based on the idea that two dimensions of competence and warmth organize the way people perceive the social world around them. The Stereotype Content Model posits that people quickly assess two fundamental dimensions— warmth and competence—to guide their decisions about and interactions with other people and social groups. Simply put, warmth perception answers the question, “What are this other’s intentions toward me?” Another (person or group) with positive, cooperative intentions appears warm, whereas another with negative, competitive, or exploitative intentions seems cold. The second question is, “Is that other able to carry out its intentions?” Another able to implement intentions is perceived as competent. And another perceived as unable to do so is perceived as incompetent. Warmth thus includes helpfulness, sincerity, friendliness, and trustworthiness, whereas competence includes efficiency, intelligence, conscientiousness, and skill.

In the first set of studies Fiske and colleagues (2002) first asked respondents to list “what various types of people do you think today’s society categorizes into groups” and they selected the 23 groups that were listed by 15% or more of the respondents. They then presented these 23 groups to different samples of respondents (including middle-aged and elderly samples) and asked them to rate each group on several items of competence (competent, confident, capable, efficient, intelligent, skillful) and on several items of warmth (friendly, well-intentioned, trustworthy, warm, good-natured, sincere). The major outcome of these studies was to show that the meaningful social groups spread out across the space created by crossing the two dimensions of warmth and competence. And in that two dimensional space, the different groups were most often organized into four clusters, each cluster located in one of the quadrants obtained by crossing the two dimensions: the warm-competent quadrant, the warm-incompetent quadrant, the cold-competent quadrant, and the cold-incompetent quadrant.

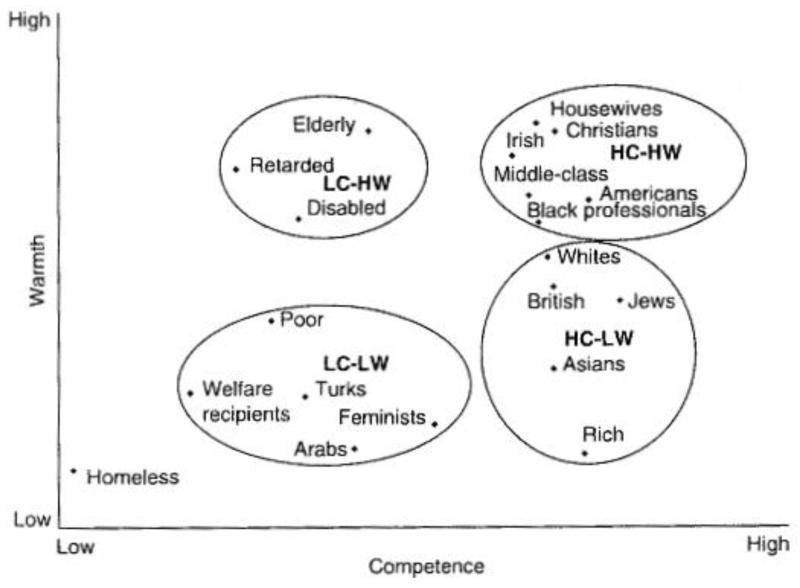

In a more recent study replicating and extending Fiske et al. (2002) on a U.S. representative sample, Cuddy et al. (2007) collected warmth and competence ratings of 20 social groups. In the results, a cluster analysis showed that these 20 groups organized into four groupings that correspond to the four quadrants obtained when crossing the warmth and the competence dimensions (see Figure 1). One cluster contained the groups rated as warm and competent that Fiske et al. (2002) called the reference groups (Americans, Middle-class). A second cluster comprised the groups perceived as cold and incompetent, the most derogated groups (welfare recipients, poor people). A third cluster comprised groups rated as warm and incompetent, the paternalized groups (elderly, disabled). The remaining cluster included the groups perceived as competent and cold, the envied groups (Asians, rich). These results thus showed that negative stereotypes can have important differences in content and that stereotypes about discriminated groups are not necessarily completely negative but often mix positive and negative content.

Figure 1.

Distribution of social groups on the competence and warmth dimension in the Stereotype Content Model (Cuddy et al., 2007).

NB: Groups labels were provided by pretest participants in another study, the specific labels are not endorsed by the authors.

The difference between the warm-competent quadrant and the cold-incompetent quadrant is obvious; a clear valence difference separates the two on both dimensions. Essentially, a wholly positive evaluation of the groups characterizes the warm-competent cluster and a wholly negative evaluation of the groups characterizes the cold-incompetent cluster. One innovation of the model is to identify the two mixed-impressions quadrants, namely, the paternalistic quadrant and the envied quadrant. Indeed, the difference between the two mixed-impressions quadrants is more subtle because each contains both positive and negative impressions that coexist, yet the two overall impressions differ a great deal. For instance, paternalized groups such as the elderly are scorned because they are perceived as being well intentioned but lacking the ability to enact those intentions. On the other hand, envied groups such as rich people are perceived as having negative intentions but also as being able to reach their goals. So the two fundamental dimensions of social perception together make sense of the different impressions about these four quadrants.

Using survey data (Cuddy et al. 2007; Fiske et al., 2002) and experimental data (Caprariello et al., 2009), researchers identified specific emotions elicited by the 4 different combinations of warmth and competence. Groups perceived as warm and competent, such as middle class, Christians, and Americans (for U.S. participants), elicit admiration. Groups seen as warm and incompetent, such as elderly and disabled people, elicit pity. Groups perceived as cold and competent, such as rich people, Asians, and Jews, elicit envy. And derogated groups seen as cold and incompetent, such as undocumented immigrants, homeless, and welfare recipients, elicit contempt. The perception of a social group on the Stereotype Content Model is thus not a mere combination of high or low warmth and competence; that combination has in turn an emotional consequence, with a specific emotion elicited for each of the four quadrants of the model.

For example, the low-low quadrant’s groups (homeless, drug addicts) elicit disgust and contempt; people report being unable to imagine a day in their life and unlikely to interact with them (Harris & Fiske, 2009). Further, the cold and competent groups that elicit envy are more likely to elicit Schadenfreude when they encounter misfortunes (Cikara & Fiske, 2011). Schadenfreude is an emotion felt when one takes pleasure at witnessing another’s trouble. For the same kind of misfortune, subjectively positive emotions (i.e., Schadenfreude) was elicited when it happened to a member of group stereotypically perceived as cold and competent (e.g., investment bankers) but not when the same misfortunes happened to members of a group stereotypically perceived as warm and competent, warm and incompetent, or cold and incompetent. These emotional reactions specific to the different quadrants of the Stereotype Content Model have been further supported by recent research in socio-neuropsychology.

Neurological evidence supporting the Stereotype Content Model

Neuro-imaging studies are beginning to show that groups from different clusters of the Stereotype Content Model elicit signature neurological responses (Cikara, Botvinick, & Fiske, 2011; Harris & Fiske, 2006; Harris & Fiske, 2007). Harris and Fiske concentrated their neuro-imaging research on the medial-prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain that is activated in essentially any social interaction or social cognition task (e.g., remembering a social interaction, thinking of a specific person, considering someone’s thoughts). For instance the medial-prefrontal cortex is activated when someone looks at a person performing a task, but it is not activated when watching a robot perform the exact same task. Participants in the scanner viewed pictures of people that clearly belonged to one of a number of social groups. The position of these groups on the two-dimensional space of the Stereotype Content Model had previously been measured. For each picture, participants were asked to rate whether watching the picture elicited admiration, envy, pity, or contempt.

Rating results showed that, as expected by the Stereotype Content Model, pictures of members of warm-competent groups elicited admiration. Pictures of members of cold-competent groups elicited envy. Pictures of warm-incompetent group members elicited pity. And pictures of members of cold-incompetent groups elicited contempt. Furthermore, the neuro-imaging data showed that the medial-prefrontal cortex was activated when participants saw pictures of members of warm-competent groups, members of cold-competent groups, and members of warm-incompetent groups, but not when participants saw pictures of the most extreme, low-low outgroups. So the main result of this experiment was to show that, unlike the members of the other groups, members of groups stereotypically perceived as cold and incompetent do not lead to significant activation of the medial-prefrontal cortex, the social interaction part of the brain. Beyond identifying a signature neurological response to cold-incompetent groups, this result further underlines the fundamentally social nature of the two dimensions of warmth and competence. In effect, members of groups seen a lacking both dimensions are dehumanized, not easily viewed as having a mind, and less worthy of social interaction than members of groups located in the three other quadrants of the Stereotype Content Model.

Research by Cikara et al. (2011) identified a signature neurological response for the cold-competent quadrant. Participants were avid fans of two rival baseball teams: the Yankees and the Red-Sox. The data first showed that fans of each team perceive the rival team as cold and competent. Then participants in the scanner viewed baseball plays. Neuro-imaging data showed that seeing the other team fail activated the ventral striatum, an area of the brain associated with subjective pleasure. Avid fans thus took pleasure in watching the rival, cold and competent, team fail. As reviewed above, this kind of subjective pleasure in others’ misfortune is called Schadenfreude. Interestingly, that malicious emotion was limited to the rival team that was perceived as cold and competent. When avid Yankees or Red Sox fans saw the Blue Jays, another team that they did not typically perceive as cold and competent, fail, the subjective pleasure part of the brain was not activated. These two lines of studies showed that beyond the traditional survey method, using a neuro-imaging method also supports the Stereotype Content Model.

Intercultural evidence supporting the Stereotype Content Model

A number of researchers have studied the applicability of warmth and competence models across cultures. For instance, stereotype content data in seven European and three Asian nations (Cuddy et al., 2009) entailed a first sample of participants asked to list the relevant social groups in their society. Then another sample of participants rated the most-often-cited groups on warmth and competence items. In all the countries, perceptions of the relevant social groups consistently spread out across the two dimensional space of the Stereotype Content Model. And these groups clustered in the four quadrants of the model. The only notable difference was that the Asian countries (Japan, South Korea, and China) showed no clear warmth-competent cluster. The ingroups and reference groups generally found in that quadrant were instead rated as moderately high on both dimensions, thus moving to the center of the two-dimensional space. Cuddy and colleagues (2009) interpreted this as being due to a norm of modesty and humility in collectivistic cultures. But the general message remains that across the world (including data recently collected in even more countries, Durante, Fiske, Kervyn, Cuddy et al., 2011), the Stereotype Content Model is a useful tool to create a meaningful and readily understandable map of social perceptions in a given society.

More evidence for the cross-cultural relevance of the two dimensions of social perception appears in the research of Ybarra, Chan, Park, Monin, Stanik, and Burnstein (2008) who studied the two dimensions of communion and agency, two dimensions that are very similar to the dimensions of warmth and competence respectively (Abele & Wojciszke, 2007). Ybarra et al. (2008) analyzed the content of Brown’s (1991) list of human universals, a list of practices observed by anthropologists in a wide variety of cultures across the globe. Ybarra et al. (2008) gave a definition of communion and of agency to independent raters. Communion was defined as practices implicating social interactions, relationships, and the regulation of interpersonal behaviors. Agency was defined as practices enabling people to perform tasks, solve problems, and attain their goals. The researchers then asked the raters to classify the 372 human universals (Brown, 1991) into 4 categories: the communion-related category, the agency-related category, the “both communion and agency-related” category and the “neither communion nor agency-related” category. Examples of universals that were classified as communion-related are: taboos; generosity admired; fairness; empathy. Examples of universals that were classified as agency-related are: mental maps; memory; tools; practice to improve skills. Examples of universals classified as “both communion and agency-related” are: dance; government; healing the sick; division of labor; collective decision making. And examples of universals classified as “neither communion nor agency-related” are: liking sweets; right-handedness as a norm; wariness of snakes; sucking wounds. A large majority (66%) of the human universals were classified into the communion-related, the agency-related or the “both communion and agency-related category.” These results further support the idea that the two fundamental dimensions of social perceptions occur across cultures.

Warmth and competence perception of other social objects

Working outside of the framework of the Stereotype Content Model, two similar dimensions, communion and agency, apparently underlie individual person perception. For example (Wojciszke, 1994) participants read instructions to remember instances that led them to a clear-cut evaluation of another person. A content analysis of 1000 such episodes showed that in 75% of them the evaluative impression related to either the communion or the agency dimension. Similar results were found in another study (Wojciszke et al., 1998) in which participants gave global evaluations of 20 persons from their social environment and then evaluated those people on communion and agency traits. The data showed that the communion and agency traits ascription accounted for 82% of the variance of the global impressions. Finally, according to Wojciszke, Abele, and Baryla (2009), the communion dimension links to liking of the target, and the agency dimension links to respect toward the target (see also Fiske, Xu, Glick, & Cuddy, 1999). So, a target perceived as high in communion is liked, whereas one perceived as low in communion is disliked. And a target perceived as high in agency is respected, whereas one low in agency is disrespected. To put it another way, a high-agency/high-communion person will be liked and respected, a low-agency/low-communion person will be disliked and disrespected, a low-agency/high-communion person will be liked but disrespected, and a high-agency/low-communion person will be disliked but respected. Wojciszke’s (1994; 2008; Wojciszke et al., 1998) model of person perception thus has similarities to the group perception model proposed by the Stereotype Content Model. As a matter of fact, the Stereotype Content Model has been shown to apply to person perception (Russell & Fiske, 2008), when individual people meet someone expected to be high or low status (predicting competence) and cooperative or competitive (predicting warmth).

The Stereotype Content Model has also been applied to the perception of countries. Cuddy et al. (2009) measured the way Europeans perceive the different countries of the European Union. As for social groups, the two dimensions of warmth and competence allowed building a meaningful map of the stereotypes attached to the different countries. Germany for instance was rated as competent but cold, whereas Portugal was rated as warm but incompetent. Interestingly, the way participants perceived their own country was generally consistent with the way their country was rated by citizens of other countries, ingroup perception thus matching other participants’ outgroups perception. To be sure, they had to rate how their country was viewed within the EU, and slight ingroup favoritism appeared. Nevertheless, the two dimensions differentiated countries’ images.

Moreover, as for person perception, most of the research on country perception has been done outside the framework of the Stereotype Content Model, but using two dimensions very similar to warmth and competence. Research by Phalet and Poppe (1997) and Poppe and Linssen (1999) measured a host of possible predictors of the perception of a country’s morality and competence. Perceived conflict between the country and the participants’ country predicted perceived warmth (Phalet & Poppe, 1997). If a country was perceived as being in conflict with the respondents’ country, then it was perceive as lacking warmth. And they found that the perceived power of a country was positively related to its perceived competence. So the more a country was perceived as a powerful nation, the more it was perceived as a competent nation. Similarly, the size of the nation was a negative predictor of its perceived warmth (Poppe & Linssen, 1999): the larger countries were rated as colder than the smaller ones. And perceived economic power and perceived political power were the main (positive) predictors of a country’s perceived competence.

Applications of the Stereotype Content Model

As reviewed above, the Stereotype Content Model and more widely the two fundamental dimensions of social perception thus provide a robust model of social perception that applies across cultures and, more importantly for our present endeavor; it demonstrably applies to a variety of social targets. It can be a useful and simple way to map a given social world, whatever the degree of granularity of the social object studied, from person perception to entire countries. It can also focus on one specific social object and identify the content of the stereotype associated to it. For instance (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2004), the two dimensions of warmth and competence describe the content of the stereotype held about working women, which changes depending on the women’s family status. Participants examined four résumés in the context of a personnel evaluation procedure. Among three filler profiles of management consultants was a profile that varied in gender and in whether the person had a child or not. These minimal manipulations allowed a comparison of the degree to which gender and parental status affect warmth and competence perceptions, and likelihood to be hired, promoted, and trained. As expected, the comparison of a working mother to a childless working woman in a professional setting was informative. In line with the Stereotype Content Model, female professionals with children were not only viewed as more warm than competent but also as warmer and less competent than female professionals without children. Even more telling, this competence penalty in impression was associated with a reluctance to reward the working mother professionally. Specifically, a working mother was rated as less likely to be hired, promoted, or trained than a female professional without children. Having children did not have a detrimental effect on the perception of male professionals. Like working mothers, working fathers were perceived as warmer than their childless counterpart, but they were not perceived as less competent or less likely to be hired, promoted, or trained. Using the Stereotype Content Model to study social perception in this kind of human resources context thus identified a more subtle kind of sexism toward working mothers. Earlier, a variety of gender subtypes for both men and women found that warmth and competence differentiated among a broad array of male and female roles (Eckes, 2002).

Another kind of application of the Stereotype Content Model (Durante, Volpato, & Fiske, 2010) used the model to analyze historic documents dating back to Italy’s fascist period. Content analysis focused on the descriptions of social groups published in a fascist magazine called “The Defense of the Race.” Italians and Aryans were described as pure race, intelligent, cheerful, and as having positive psychological characteristics. The outgroups appeared in two clusters. Blacks and “half-castes” were described as stupid, miserable, dark, dishonest, and complaining, whereas the Jews and the English were described as loan-sharks, crucifiers, dishonest, corruptors, and greedy. Going beyond the fascist rhetoric, these descriptions clearly correspond to three of the four quadrants of the Stereotype Content Model. Italians and Aryans, respectively the ingroup and the aspirational group, are described as warm and competent. Blacks and mixed-race people are described as cold and incompetent. And Jews and English people are described as cold and competent. This historical analysis shows that even an extremist totalitarian regime that was obsessed with race still had a perception of the differences between social groups that corresponds to the Stereotype Content Model. This research also shows that in the fascist perception of the social world there was no social group in the pitied quadrant.

The content of the stereotype of Jews in Italy during the fascist regime is particularly interesting. As reviewed above (Cikara & Fiske, 2011), it is this kind of envied groups that elicit Schadenfreude. Cikara and Fiske (2011) used mundane misfortunes such as walking into a glass door, but the case of the fascists’ perception of the Jews shows that groups that are the object of this kind of cold-competent stereotypes are also those that have been the victim of the most extreme cases of intergroup aggression. Indeed, the groups that have been the victims of genocides and ethnic cleansing are typically perceived as cold (untrustworthy) but competent because they are the most threatening. This is the case for Armenians in Turkey at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Asian community of Uganda in the seventies, the Chinese in Indonesia in the eighties, the Tutsis in Rwanda in the nineties, and Jews fairly much throughout history.

The Social Perception of Brands

Fournier (1998; 2009) was the first to propose that people relate to brands in their life quite similarly to the way they relate to people around them. Fournier developed this insight from a series of in-depth interviews of consumers. An pertinent example coming out of these interviews concerns Karen, a divorced working mother who reported negative affects toward a number of brands that reminded her of her ex-husband. Karen actively avoided those brands. Fournier (1998) calls this an “Enmity” type of brand relationship. Another example concerns Vicky, a college student who used a number of brands because her mother used them before her. Fournier (1998) named this kind of non-voluntary, inherited brand relationships “Kinship.” This idea that people relate to the brands in a social way led us to the hypothesis that a model of social perception such as the Stereotype Content Model could also apply to brand perception. But Fournier’s generative work is not the only brand perception research that leads to that hypothesis. For instance, Mark and Pearson (2001) in their book titled “The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes” argue that successful brands need to present themselves to consumers as archetypes such as those that can be found in fictions. According to Mark and Pearson (2001), brand managers need to identify the kind of archetype that their brands belongs to or wants to belong to and build a coherent communication around that archetype. Providing this kind of archetypal image then makes it more likely that consumers will forge a strong relationship with the brand. An example of a brand that has successfully identified and embraced the archetype called “the outlaw” is Harley-Davidson. The outlaw archetype fits a powerful brand focused on achievement that is able to take risks and to break the rules. Research by McAlexander, Schouten, and Koenig (2002) has showed how this archetypal brand image has allowed Harley to build a strong brand community. Going beyond consumer-brand relationships, brands are also perceived to have relationships with other brands. Certain brand are successfully portraying themselves as the underdog facing much stronger competitors thus motivating consumers to buy the brand as a sign of support for the popular underdog role (Paharia, Avery, and Keinan, 2011). For instance Sam Adam’s consistently portrays itself as being a very small player in the brewing industry dominated by much larger brewers despite the fact that they have actually become quite an important player on the US brewing market.

In an approach related to the model that we propose here, Aaker (1997, see also Zentes, Morschett, & Schramm-Klein, 2008) has created a brand personality scale. That scale comprises 15 facets combined into 5 factors: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. Sincerity relates to traits such as honest and genuine. Excitement relates to traits such as spirited, daring, and imaginative. Competence relates to traits such as efficient, dependable, and reliable. Sophistication relates to traits such as glamorous and pretentious. And ruggedness relates to traits such as tough, strong, and outdoorsy. First, note that as in the Stereotype Content Model, Aaker’s scale has a competence factor. We also see similarities between the Aaker sincerity factor and the warmth dimension. And we would interpret the ruggedness factor as combining low warmth and high competence, also linked to stereotypical masculinity (Eagly & Steffen, 1984). So there are clear links between our brand perception model and Aaker’s (1997) brand personality scale. But we consider that just as psychology shows a clear difference between personality scales (what a person is) and social perception (how a person seems), the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework we propose in this paper is a different tool to be used for a different purpose than Aaker’s personality scale. Personality scales make sense when focusing on one or on a small number of brands, to provide a more detailed description of their actual attributes. Social perception models on the other hand allow researchers to measure perception of a larger number of social objects, thus creating a whole landscape in which the images of all the relevant objects can be located and compared.

In the literature on brand perception, a number of concepts might be interpreted as fitting elements of the Stereotype Content Model. On the one hand, looking at a brand’s performance features—such as quality, reliability, durability, and consistency—could be interpreted as different ways to approach a brand’s competence. On the other hand, assessing brands through terms such as brand love (Ahuvia, 2005) or brand passion (Noel, Merunka, & Valette-Florence, 2010) might be interpreted as a brand’s perceived warmth. In an experiment with a conceptual background close to ours, Aaker, Vohs, and Mogilner (2010) have shown that non-profit brands are perceived as warmer but also less competent than for-profit brands. Aaker and colleagues (2010) asked their participants to look at a company webpage presenting a product, an Ogio-designed messenger bag. They were then asked to rate the company on warmth and competence traits. For half of the participants the website of the company had a .com domain name typical of for-profit organizations. And for the other half, the website of the company had a .org domain name typical of nonprofit organizations. That simple manipulation of domain name was enough to get the participants in the .org, nonprofit condition to rate the company as less competent and warmer than in the .com, for-profit condition.

Finally, research by Thomson and colleagues (2005) has shown an emotional aspect to brand equity. Thus, the BIAF we propose seeks not to introduce entirely new dimensions of brand perception, but it has the distinctive advantage of crossing these two dimensions to predict images, emotions, and behaviors. It provides an overarching model of brand perception and consumer behavior that is rooted in social-perception psychology.

The Brands as Intentional Agents Framework

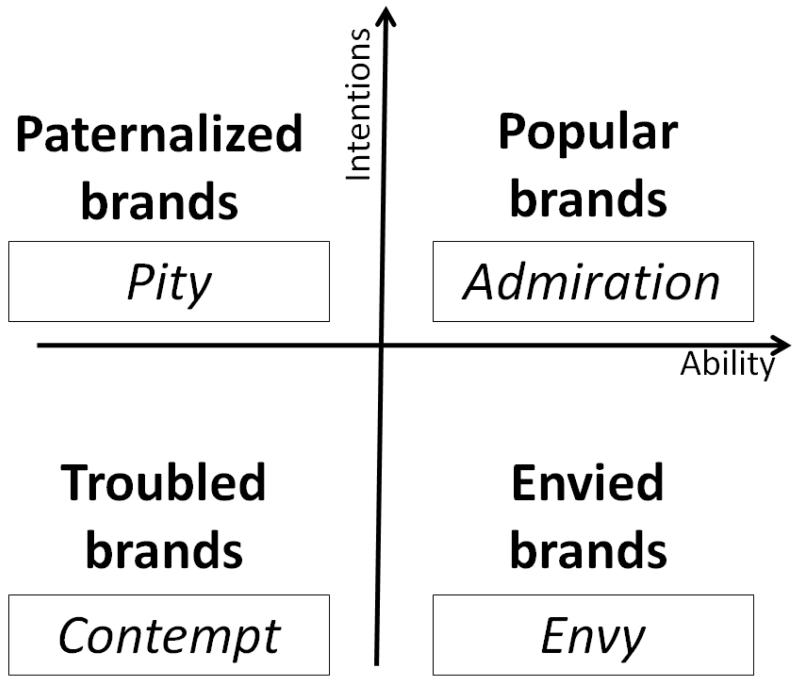

The broad range of social objects – from individuals to countries – to which the Stereotype Content Model applies led us to theorize that if consumers enter into relationships with brands that resemble the relationships they have with people (Fournier, 1998), then the model used to organize the way social perception works should also apply to brand perception. We thus developed the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework (BIAF) as an adaptation of the Stereotype Content Model to fit brand perception. In order to make that transition from social to brand perception, a number of adaptations were necessary. Rather than using the personality traits of “warm” and “competent” to name the two dimensions of the BIAF, we will call these two dimensions “intentions” and “ability” to emphasize the way these perceptions imply a corporate entity as having intentions and the ability to enact those intentions. This mostly cosmetic change fits the way the Stereotype Content Model theorizes (Fiske et al., 2002; 2007), for warmth is defined as the perceived intentions of a social group/person and competence as ability to carry out these intentions. Therefore, we propose a Brands as Intentional Agents Framework (BIAF) (summarized in Figure 2) in which brands will differ in how well (or ill) intentioned they seem to be, as well as on how able they are perceived to be. As with social groups in the Stereotype Content Model, if our BIAF is valid, different brands should be perceived as able/well-intentioned, unable/ill-intentioned, able/ill-intentioned, and unable/well-intentioned.And these four combinations of intentions and ability should elicit specific emotions. Brands perceived as able and well-intentioned are expected to elicit admiration. Brands seen as unable but well-intentioned should elicit pity. Brands perceived as able but ill-intentioned should elicit envy. And brands generally perceived as unable and ill-intentioned are expected to elicit contempt. In order to make this BIAF relevant to marketing professionals, we also test our prediction that these different perceptions will be valuable predictors of the way consumers behave toward different brands. Namely, we think that brands’ perceived intentions and ability will predict purchase intent and brand loyalty.

Figure 2.

Brands as Intentional Agents Framework dimensions, clusters and emotions.

The four quadrants of the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework

As reviewed above, across time and across cultures, some social groups consistently end up in the same quadrant of the Stereotype Content Model. The elderly for instance are consistently rated as warm but incompetent in all the data collection run over the last decade and in a large number of different countries. We believe that it is also possible to identify brands that will reliably be rated as belonging to each of the four quadrants of the BIAF. In the well-intentioned, high-ability quadrant, we expect to find popular and successful brands, as we thought that in order to become and remain successful and popular, brands have to be perceived as high on both positive intentions and ability. In the ill-intentioned, low-ability quadrant, we expect to find troubled but well-known brands that have been the focus of negative press coverage in the recent past. In the high-ability, ill-intentioned quadrant, we expect to find luxury brands. Indeed we think that these brands are the most likely to be perceived as combining high ability with negative intention (or at least no particularly good intentions) toward the general public, as they specifically target consumers more wealthy than average. Finally in the well-intentioned, low-ability quadrant, we would expect brands that need to be externally supported by government-subsidy funding to remain viable. To deserve support, these brands should be perceived as having positive intentions, but they should also be perceived as having low ability, and so in need of subsidy funding.

Experimental test of the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework

We conducted an experiment as a first test of our conceptual model. We manipulated the stated intentions and ability of a hypothetical brand and measured the inferred warmth, competence, elicited emotions, as well as behavioral tendencies toward that brand. Based on the proposed BIAF, we derived a number of specific hypotheses. Well-intentioned brands will be rated higher on warmth than ill-intentioned brands (H1), and high-ability brands will be rated higher on competence than low-ability brands (H2).Well-intentioned brands will be rated higher on admiration (H3) and pity (H4) than ill-intentioned brands. And they will be rated lower on envy (H5) and contempt (H6) than ill-intentioned brands. High-ability brands will be rated higher on admiration (H7) and envy (H8) than low-ability brands. And they will be rated lower on pity (H9) and contempt (H10) than low-ability brands. Finally, well-intentioned brands will be rated higher on purchase intent (H11) and loyalty (H12) than ill-intentioned brands. And high-ability brands will be rated higher on purchase intent (H13) and loyalty (H14) than low-ability brands.

Methods

In a first study, adults participants recruited on-line across the US read about a single hypothetical brand that had either positive or negative intentions and was either high or low on ability. Participants read that “Brand A is largely seen as consistently acting with (without) the public’s best interests in mind and having (lacking) good intentions toward ordinary people. Brand A is also seen as being (un)skilled and (in)effective at achieving its goals and having (lacking) the ability to implement its intentions.” Participants then rated that brand on two warmth items (warm, friendly), two competence items (competent, capable), four emotion items (admiration, pity, envy, contempt), as well as two behavioral intention items (purchase intent, brand loyalty).

Results

For the warmth score, as expected, well-intentioned brands received much higher warmth ratings than ill-intentioned brands (H1). Although not predicted, high-ability brands received marginally higher warmth ratings than low-ability brands. For the competence score, high-ability brands were much more competent than low-ability brands (H2). And well-intentioned brands were rated as somewhat more competent than ill-intentioned brands. We then analyzed the elicited emotions. Well-intentioned brands elicited more admiration than ill-intentioned brands (H3). But these well-intentioned brands did not elicit more pity than ill-intentioned brands (contrary to H4). And the ill-intentioned brands did not elicit more envy than well-intentioned brands (contrary to H5). Finally, as expected, the ill-intentioned brands elicited more contempt than well-intentioned brands (H6). We then looked at the effect of the ability manipulation. As expected, the high-ability brands elicited more admiration (H7) and more envy (H8) than low-ability brands. Also as expected, low-ability brands elicited more pity (H9) and more contempt (H10) than high-ability brands. Furthermore, the impact of the intention on admiration and on contempt was mediated by warmth. Similarly, the impact of ability on all four emotions was mediated by perceived competence.

Finally, we analyzed the results of the behavioral intentions. As expected, well-intentioned brands received higher purchase intent (H11) and loyalty (H12) than ill-intentioned brands. And high-ability brands received higher purchase intent (H13) and loyalty (H14) than low-ability brands. Furthermore, admiration mediated the impact of the intention manipulation on purchase intent and on brand loyalty. Elicited admiration was also a partial mediator of the impact of the ability manipulation on purchase intent and on brand loyalty.

Discussion

These results offer strong support for our BIAF. Of 14 hypotheses, 12 were supported. First, the reframing of warmth and competence as intentions and ability was supported. The warmth scores were directly related to the intentions manipulation. And the competence scores were directly related to the ability manipulation. Our use of intentions and ability as the two dimensions instead of warmth and competence thus not only makes sense at the theoretical level but also fits our data. Concerning the elicited emotions, as expected, both the intentions and the ability manipulation had the expected positive effect on elicited admiration and negative effect on elicited contempt. Envy and pity, however, each showed only a main effect of the ability manipulation. High-ability brands elicited more envy and less pity than low-ability brands. The expected effects of intentions on those two emotions were not supported. Results on elicited emotions thus confirm that the emotional level of our BIAF is largely supported; however we will have to see if the lack of impact of the intentions manipulation on elicited envy and pity is confirmed in Study 2 and in what way that lack of effect can be interpreted. Finally, testing our hypotheses on behavioral tendencies, results showed that as expected each dimension of social perception had a significant, independent, predictive impact on purchase intent and brand loyalty. These effects of the intention and ability manipulation on purchase and loyalty were both mediated by admiration.

Using the BIAF to study the perception of 16 brands

This second study aimed to test our hypotheses further using actual brands. To do so, a survey answered by a sample of US adults recruited on the web tested the BIAF on perception of 16 well-known brands. To test the BIAF hypotheses we selected 16 brands, four for each quadrant following the rationale developed above concerning the four quadrants of the BIAF and the kind of brands that we expect to belong in each of them. The four popular brands were Hershey’s, Johnson & Johnson, Campbell’s, and Coca-Cola. The four troubled brands (as of the academic year 2010-11) were BP, Goldman Sachs, Marlboro, and AIG. The four luxury brands were Rolex, Rolls Royce, Porsche, and Mercedes. And the four externally supported brands were the U.S. Postal Service (USPS), veterans hospitals (VA), Amtrak, and public transportation.

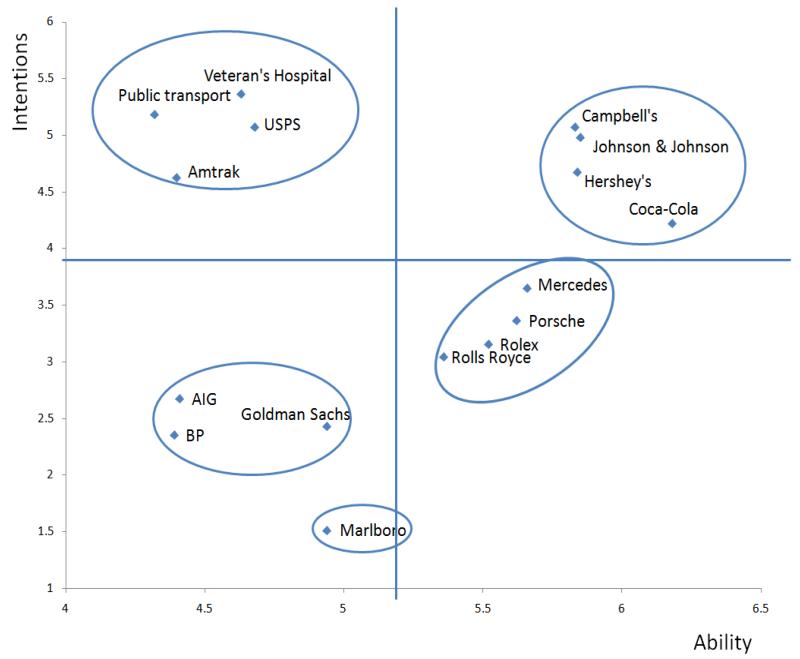

Results

We used a cluster analysis to determine which brand fit into which cluster (see Figure 3). One cluster indeed comprised the four a priori popular brands: Hershey’s, Johnson & Johnson, Campbell’s, and Coca-Cola. Another cluster likewise included the four a priori subsidized brands: USPS, Veterans Hospitals, Amtrak, and Public Transportation. A third cluster similarly comprised the four luxury brands: Rolex, Rolls Royce, Porsche, and Mercedes. A fourth cluster comprised three of the four a priori troubled brands: BP, Goldman Sachs, and AIG. Finally, the fourth a priori troubled brand, Marlboro, formed a fifth cluster, even lower than the other troubled brands on perceived intentions.

Figure 3.

Intention and ability scores of the 16 brands, mean intention and ability scores, and cluster groupings (Study 2).

For the popular-brands cluster, as predicted, all four brands were above the respective grand means on intention and ability. For the subsidized-brands cluster, all four brands were above the grand mean on intention but below the grand mean on ability. For the luxury brands cluster, two of the brands’ (Rolex and Porsche) means were below the grand mean on intention, and above the grand mean on ability. Rolls Royce’s intention score was below the mean, but the ability score was not different from the mean. Mercedes’ intention score was not different from the mean, and the ability score was above the mean. Thus, 6 of 8 predictions were supported for this cluster.

For the troubled brands clusters, two of the brands’ (BP and AIG) means were either at or below the two respective grand means. Goldman Sachs’ intention score was below the mean but the ability score was not different from the mean. In the fifth cluster, Marlboro’s intention score was below the mean, but the ability score was not different from the mean. Again, 6 of 8 predictions were supported.

We then analyzed the elicited emotion scores. For the popular-brands cluster, as expected, all four brands were above the grand mean of admiration. For the subsidized-brands cluster, three out of four (USPS, VA, and public transportation) elicited significant higher pity than average. Amtrak’s pity score was not different from the mean. For the luxury-brands cluster, as expected all four brands were above the grand mean of envy. For the two troubled-brands clusters, all four brands were above the grand mean of contempt.

We then tested BIAF structure hypotheses as in Study 1. As expected, admiration was positively predicted by both intentions and ability. Pity was negatively predicted by ability, but intention was not a significant predictor. Envy was positively predicted by ability, but intention was not a significant predictor. And contempt was negatively predicted by both intentions and ability. Thus, 6 of 8 predictions were supported, and the remaining 2 were in the predicted direction.

To test the BIAF behavioral-tendencies hypotheses, we ran two separate linear regressions with purchase intent and brand loyalty as dependent variables and intentions, ability, and intention by ability interaction as predictors. As expected, purchase intent was positively and independently predicted by both intentions and ability. These simple slopes were not qualified by an interaction. And brand loyalty was also positively and independently predicted by both intentions and ability. The interaction was not a significant predictor of loyalty.

Discussion

Consumers’ perception of 16 well-known brands supported the BIAF. In the intention-by-ability space, the four popular brands clustered together in the well-intentioned and able quadrant. The four luxury brands clustered together in the ill-intentioned and able quadrant. And the four subsidized brands clustered together in the well-intentioned and unable quadrant. For the contempt brands, three brands clustered together clustered together in the ill-intentioned and unable quadrant, and Marlboro formed a separate cluster because its intention ratings were even lower than the other troubled brands. And, despite a few non-significant differences, beyond the fact that they clustered together in the expected quadrant, the different brands did differ from the general intentions and ability means in the expected ways: popular brands higher than the average on both dimensions, troubled brands lower than average on both, luxury brands higher on ability but lower on intentions, and subsidized brands higher on intentions but lower on ability.

Furthermore, the emotions elicited by these different brands supported the BIAF predictions. Popular brands elicited higher admiration, troubled brands elicited higher contempt, luxury brands elicited higher envy, and three of the four subsidized brands elicited higher pity scores than average. We note however that the intentions items asked what the brand’s intentions were toward “the general public.” Thus, perhaps the actual clients of luxury brands for instance might perceive those brands as well intentioned toward them, but our data show that it is not the perception of the public at large.

As for the prediction of elicited emotions and behavioral variables by intentions and ability perceptions, the survey’s correlational results replicated completely the experimental results found in the experimental test of the BIAF. So, both the intentions and the ability perceptions were positive predictors of elicited admiration and negative predictors of elicited contempt. For envy and pity, ability was a significant predictor in the expected direction. But, as in the experiment, we found no significant link between intention perception and these two ambivalent emotions. For the outcome variables, intention and ability perceptions each turned out to be two significant independent positive predictors of purchase intent and brand loyalty. This is particularly important, for it shows an added value of the BIAF in understanding and influencing consumer behavior. As each dimension has significant predictive power over and above the other one, using both intentions and ability perceptions allows for a better prediction of consumer behavior than a single dimension model.

General Discussion

Both studies support our Brands as Intentional Agents Framework (BIAF), with its central claim that brands are seen as intentional agents and thus that their perceived intentions and ability are important dimensions underlying brand perception. This notion that people are able to attribute phenomenal mental states such as positive or negative intentions to non-social objects has already been made in the field of philosophy (Arico, 2010) although it is not universally accepted (Knobe & Prinz, 2008).

In total, our findings have significant implications for brand marketers and researchers. First, our testing designs and instruments for evaluating brands produced results that are remarkably similar to those of the Stereotype Content Model, which has been widely validated in the study of human social perception. As expected, each group of brands was perceived by consumers to have a distinct intentions-and-ability profile that tended to elicit predictable patterns of emotions and behavior. While consumer emotions of pity and envy toward brands were found to be far less predictable than expected, the balance of our perception, emotion, and behavior hypotheses were supported by our data. This is especially significant in that it suggests that consumers do perceive, feel, and behave toward brands in ways that closely mirror those toward other people and social groups. In addition, it suggests that other models of human social perception might also prove valuable in understanding and influencing consumer behavior. Further research on the social perception of brands may help explain frequently shifting loyalty among established brands and the rapid adoption of new ones.

Our findings regarding the influence and impact of brands’ perceived intentions and ability on purchase intent and brand loyalty are also striking. Traditionally, when studying brand equity, marketers look at a brand’s intrinsic features and benefits that are considered to be the primary drivers of consumer behavior. Our data suggest however that a brand’s perceived relational intentions are also strong predictors of purchase intent and brand loyalty behavior over and above a brand’s perceived ability. Consumers’ natural sensitivity to the intentions of others would therefore seem to be playing a much larger role in brand behavior than previously understood. In light of the increasing skepticism and distrust many consumers now hold toward large brands and companies, our findings suggest that efforts to maximize shareholder value may now be perceived by consumers as negative intentions and that large brands are often not acting in the public’s best interests. An important message of the BIAF is thus to suggest adding perceived brand intentions to more traditional features and benefits when measuring brand equity.

Apparently, other business thought-leaders may be reaching a similar conclusion, though by a different path. For instance, we interpret Pepsico’s “Performance with Purpose” strategy and Porter and Kramer’s (2011) recent Harvard Business Review paper on “Creating Shared Value” as good examples of leaders in the business community arguing for the need to better balance their emphasis on ability with demonstrably honorable intentions. Another example of brand managers having intuitively followed lessons that would arise from the BIAF comes from brands that purposefully create a different brand in order to occupy a different part of the BIAF two-dimensional space. A good example of this kind of differentiation strategy is Lexus. Aat the end of the eighties Toyota decided to produce luxury vehicles. The brand had, and still has, a strong image as producing affordable and dependable cars, so it is thus typically seen as a warm-competent brand. But in order to reach the high-end clients they wanted to convey the image of a luxury brand that, as we have shown, is expected to portray a high ability, low intentions (toward the general public) image. Therefore they created Lexus, a brand with a different name and different brand image so that Toyota as a group could convey simultaneously two very different brand images. Or to say it in BIAF terms so that the group could be present both in the well-intentioned and able and the ill-intentioned and able quadrant.

Another possible useful outcome of the BIAF is to use it as a tool to construct comprehensive and readily understandable maps of brands perception in a specific market/category. Just like the Stereotype Content Model was successfully used to build social perceptions maps in various countries (Cuddy et al., 2009; Durante et al., 2011) using the relevant groups in each country, the BIAF could be used to place on the two dimensions the brands that have been identified as relevant brands in a specific market/category. Having this brand perception map would be a meaningful first step for a brand manager to understand how his/her brand is positioned relative to competitors, on what dimensions improvements are most needed and what kind of emotions the brand is likely to elicit from consumers.

Wrapping up, we consider that the main message of our theoretical and experimental work on the Brands as Intentional Agents Framework is that consumers perceive, feel, and behave toward brands in ways that are similar to their interactions with other people and social groups. The important implication for brand researchers, marketers, and managers is that, as with human social interactions, the intrinsic warmth and intention perceptions by consumers are playing a highly significant role in consumer behavior toward brands, but these are likely not as well understood or managed as is needed to build and maintain lasting brand purchase and loyalty.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Pr. J. Avery, Pr. R. Hill and Pr. A. Bennett for their insightful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Appendix A. Predictors used in Study 2

Intention & Ability items

Please indicate how well the following statements describe BRAND:

Has good intentions toward ordinary people.

Consistently acts with the public’s best interests in mind.

Has the ability to implement its intentions.

Is skilled and effective at achieving its goals.

Emotion items

Please indicate the degree to which you feel the following emotions toward BRAND

Admiration

Pity

Envy

Contempt

Behavior intentions items

How likely you would be to make a purchase of, or donation to, BRAND if you had the money necessary to do so?

How strong and loyal a preference you feel for BRAND?

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nicolas Kervyn, University of Louvain, Belgian Science Fund (FRS).

Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University

Chris Malone, Relational Capital Group.

References

- Aaker J. Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research. 1997;34(3):347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker JL, Fournier SM, Brasel SA. When good brands do bad. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004;31:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker J, Vohs K, Mogilner C. Non-profits are seen as warm and for-profits as competent: firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37:277–291. [Google Scholar]

- Abele A. The dynamics of masculine-agentic and feminine-communal traits: Findings from a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:768–776. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abele AE, Wojciszke B. Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:751–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuvia AC. Beyond the extended self: loved objects and consumers’ identity narratives. Journal of Consumer Research. 2005;32(1):171–84. [Google Scholar]

- Albert N, Merunka D, Valette-Florence P. Passion for the Brand and Consumer Brand Relationships. Australian and New Zeland Marketing Academy; Dunedin (NZ): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Arico A. Folk psychology, consciousness, and context effects. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 2010;1:371–393. [Google Scholar]

- Asbrock F. Stereotypes of social groups in Germany in terms of warmth and competence. Social Psychology. 2010;41:76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Asbrock F, Nieuwoudt C, Duckitt J, Sibley CG. Societal stereotypes and the legitimation of intergroup behaviour in Germany and New Zealand. Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown DE. Human universals. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Caprariello P, Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST. Social structure shapes cultural stereotypes and emotions: A causal test of the Stereotype Content Model. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2009;12:147–155. doi: 10.1177/1368430208101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cikara M, Farnsworth RA, Harris LT, Fiske ST. On the wrong side of the trolley track: Neural correlates of relative social valuation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5:404–413. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cikara M, Fiske ST. Bounded empathy: Neural responses to outgroups’ (mis)fortunes. Social Psychology and Personality Science. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00069. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;4:701–718. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:631–648. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Kwan VSY, Glick P, Demoulin S, Leyens J.-Ph., Bond M, et al. Stereotype Content Model across cultures: Universal similarities and some differences. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;48:1–33. doi: 10.1348/014466608X314935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante F, Volpato C, Fiske ST. Using the Stereotype Content Model to examine group depictions in Fascism: An archival approach. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;39:1–19. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante F, Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Kervyn N, et al. Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. under review. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly A, Steffen V. Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:735–754. [Google Scholar]

- Eckes T. Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: Testing predictions from the stereotype content model. Sex Roles. 2002;47(3-4):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. Universal dimensions of social perception: Warmth, then competence. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from the perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske S, Xu J, Cuddy A, Glick P. (Dis)respecting versus (dis)liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55:473–491. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S. Consumers and their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1998;24:343–373. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S. Lessons learned about consumers’ relationships with their brands. In: Priester J, MacInnis D, Park CW, editors. Handbook of brand relationships. N.Y. Society for Consumer Psychology and M. E. Sharp; 2009. pp. 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Harris LT, Fiske ST. Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuro-imaging responses to extreme outgroups. Psychological Science. 2006;17:847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LT, Fiske ST. Social groups that elicit disgust are differentially processed in the mPFC. Social Cognitive Affective Neuroscience. 2007;2:45–51. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LT, Fiske ST. Dehumanized perception: The social neuroscience of thinking (or not thinking) about disgusting people. In: Hewstone M, Stroebe W, editors. European Review of Social Psychology. Vol. 20. Wiley; London: 2009. pp. 192–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kervyn N, Fiske ST, Yzerbyt Y. Why is the primary dimension of social cognition so hard to predict? Symbolic and realistic threats together predict warmth in the stereotype content model. under review. Unpublished manuscript. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobe J, Prinz J. Intuitions about consciousness: Experimental studies. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences. 2008;7:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- MacInnis D, Park CW, Priester JR, editors. Handbook of brand relationships. M. E. Sharpe; Armonk, NY: [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Pearson CS. The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes. McGraw-Hill; New York NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McAlexander JH, Schouten JW, Koenig H. Building Brand Community. Journal of Marketing. 2002:38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Phalet K, Poppe E. Competence and morality dimensions in national and ethnic stereotypes: A study in six eastern-European countries. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1997;27:703–723. [Google Scholar]

- Poppe E, Linssen H. In-group favouritism and the reflection of realistic dimensions of difference between national states in Central and Eastern European nationality stereotypes. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1999;38:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Porter M, Kramer M. Creating Shared Value. How to reinvent capitalism – and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business review. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Russell AM, Fiske ST. It’s all relative: Social position and interpersonal perception. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:1193–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson M, MacInnis DJ, Park CW. The ties that bind: measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2005;15:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke B. Multiple meanings of behavior: Construing actions in terms of competence or morality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:222–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke B. Morality and competence in person and self perception. European Review of Social Psychology. 2005;16:155–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke B, Abele AE, Baryla W. Two dimensions of interpersonal attitudes: Liking depends on communion, respect depends on agency. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;39:973–990. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke B, Bazinska R, Jaworski M. On the dominance of moral categories in impression formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:1251–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra O, Chan E, Park H, Monin B, Stanik C, Burnstein E. Life’s recurring challenges and the fundamental dimensions: an integration and its implications for cultural differences and similarities. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:1083–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Zentes J, Morschett D, Schramm-Klein H. Brand Personality of Retailers – An Analysis of its Applicability and its Effect on Store Loyalty. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research. 2008;18:167–184. [Google Scholar]