Abstract

The present study examines how target group’s stereotype content (on warmth and competence dimensions) influences subsequent target evaluation following self-threat related to one’s competence. Participants first received threatening or non-threatening feedback on their competence. They evaluated then a job candidate who was stereotyped either as competent and cold (Asian) or as warm and incompetent (working mother). As predicted, threatened participants derogated only the Asian target on her perceived warmth and her suitability for a job, but did not derogate the working mother. Moreover, perceived warmth mediated the observed differences in the evaluation of the targets’ job suitability. These results extend research on self-threat and prejudice by including Stereotype Content Model in this link.

Keywords: Self-threat, Motivation, Stereotyping, Stereotype-content

People’s motivation to maintain a positive self-image has been shown to lead to negative evaluations of stereotyped targets. Although individuals differ in their chronic motivation to maintain a positive self-image, specific events that threaten one’s positive self-image can activate this motivation. Self-threat decreases self-esteem (Baumeister & Tice, 1985) and consequently, people engage in strategies to restore their self-esteem and positive self-image. Fein and Spencer (1997) showed that one of these strategies includes derogating members of stereotyped group. That is, self-threat increases negative evaluation of stereotyped targets.

These authors first gave participants false negative (i.e. self-threatening) or positive feedback on an alleged I.Q. test. Participants then evaluated a job candidate who was either Jewish (i.e., JAP: “Jewish American Princess”) or Italian. Results showed that following self-threat, participants evaluated the Jewish candidate more negatively than the Italian candidate. This effect was not found following positive feedback. Though both of these targets are members of stereotyped outgroups, only the Jewish target was derogated. The findings suggest that derogating outgroup targets follows self-threat, but not all outgroup members are relevant to satisfy the motivation to maintain a positive self-image.

In this article, we examine a potential moderator between self-threat and prejudice, namely the characteristics of the target group being evaluated. We suggest that not all (stereotyped) targets are appropriate to satisfy one’s motivation to restore a positive self-image following a threat. According to Fein and Spencer, only negatively stereotyped targets (e.g., JAP, homosexuals) are likely to be derogated following self-threat. As these authors argued, the JAP stereotype is globally speaking more negative than the Italian stereotype. Thus, negative stereotypes may justify the negative evaluation of targets (Kunda & Spencer, 2003). However, as proposed by the Stereotype Content Model (SCM, Fiske, Cuddy, Glick & Xu, 2002; Fiske, Xu, Cuddy & Glick, 1999), many outgroups are the objects of negative stereotyping, but not for the same reason. The current work aims to refine the self-threat stereotype link by including the target stereotype content. This research will also refine the SCM by showing that distinct kinds of self-threat motivate differential usage of the stereotype content dimensions.

Stereotype Content Model

Fiske et al.’s (2002) work revealed that stereotype content varies along two main dimensions: Competence and warmth. Perceived levels of competence and warmth indicate to what extent a group is respected and liked, respectively. Two main kinds of mixed stereotypes can thus be derived: Paternalistic stereotypes include groups perceived as warm but not competent (e.g., housewives) and envious stereotypes include groups perceived as competent but not warm (e.g., professionals). The majority of stereotypes associated with (out)groups are mixed (i.e., high on one dimension but low on the other) and consequently do not elicit a purely positive vs. negative feeling, but rather, that of ambivalence. According to Fiske et al. (2002), paternalized groups elicit pity and sympathy. Such feelings appear when the target group is not perceived as a potential competitor of the ingroup (Cottrell & Neuberg, 2005; Smith, 2000). In contrast, groups perceived as competent and not warm inspire envy and admiration. These feelings are elicited when ingroup members face an outgroup that risks taking the ingroup’s resources (Smith, 2000).

The SCM offers a useful perspective to understand the original results obtained by Fein and Spencer (1997). Their targets differed not only in valence, but also in other dimensions related to their group’s stereotype content. The Jewish target belongs to an envied stereotyped group, perceived as competent but not warm. In contrast, the Italian target is perceived as warm but not competent (Cuddy, Fiske, Kwan, Glick, Demoulin, Bond, et al., in press), which corresponds to a paternalistic stereotype. The two targets differed thus on more than stereotype valence, but also on the dimensions of competence and warmth. The present study incorporates these dimensions. Additionally, threat could also be linked to stereotype content, as argued below.

Dimension of Threat

The SCM suggests several hypotheses about which groups should be derogated following self-threat. The dimension on which threat is experienced may play a crucial role in the perceived relevance of the target to satisfy the motivation to restore self-esteem. Previous research has shown that, following self-threat, the distinction between ingroup and outgroup must be relevant for outgroup derogation to take place. For instance, this distinction should have evaluative implications for the ingroup (Crocker, Thompson, McGraw & Ingerman, 1987; Forgas & Fiedler, 1996). Consequently, we propose that, following self-threat on a specific dimension (e.g., competence), relevant targets will be those whose group is stereotypically perceived as high on that dimension. Thus, congruency between the dimension of threat and the stereotype of the target group should be crucial in subsequent derogation of the target.

In line with our argument, Smith (2000) suggested that following a threat to their competence, people experience different emotions. These emotions vary as a function of the perceived competence of the comparison target. When the target is perceived as incompetent, such as a member of a paternalized outgroup, individuals experience pity and sympathy toward this target. As shown by Fein and Spencer (1997), in this situation, threatened participants do not derogate the target. However, when the target is perceived as competent, individuals should experience envy. Fein and Spencer (1997) showed, in this situation, that threatened participants did derogate the target. Thus, when the target stereotypically possesses the threatened competence, his or her stereotype is relevant to one’s self-enhancement goal, which should lead to target derogation.

Overview of the study

We hypothesized that, following a threat on competence, the stereotype content of the target’s group would moderate the expected negative evaluation of the target. In the study, participants completed a bogus intelligence test. They received false positive, false negative, or no feedback on their performance. Next, they evaluated a job candidate on her personality and suitability for a job. The candidate was identified as Asian American, stereotyped as competent but not warm (Fiske et al., 2002), or as a working mother, stereotyped as warm but not competent (Cuddy, Fiske, & Glick, 2004).

We expected that participants who experience threat to their competence would derogate the target stereotyped as competent but not warm. More specifically, we predicted that, compared to non-threatening feedback (i.e., positive and control), negative (i.e., threatening) feedback would lead participants to evaluate the Asian American target as less suited for the job than the working mother.

Furthermore, negative stereotypes justify the derogation of stereotyped targets (Kunda & Spencer, 2003). Indeed, Asian Americans (positively stereotyped on competence) are discriminated against because of their negative stereotype on warmth or lack of sociability (Lin, Kwan, Cheug, & Fiske, 2005). Thus, we expected negative feedback to lead participants to evaluate the Asian American target as less warm than the working mother, in contrast to non-threatening feedback (i.e. positive, control). Moreover, we predicted that perceived warmth would mediate the expected differences in the evaluation of candidates’ suitability for the job.

Method

Participants

One hundred undergraduate students at Princeton University participated in this study in exchange for course credit. Eight participants were excluded from analyses because seven were Asian Americans themselves and one guessed the true purpose of the study. Analyses reported here are based on 92 participants (30 males and 62 females), with a mean age of 19.5 years (SD = 1.23). No interaction with the participants’ gender was found, this will not be discussed further.

Procedure

Participants were recruited for a study on social evaluation. When they arrived in the laboratory, the experimenter told them that a colleague of hers needed participants to complete a short test. All participants agreed to help and completed the Remote Associate Test (R.A.T., Mednick, 1968), presented as the Analytic Logic Test. The task in the R.A.T. involved finding a word that links three apparently unrelated words. We chose twelve relatively difficult items, based on McFarlin and Blascovich’s norms (1984).

Positive and negative feedback conditions

In both conditions, the Analytic Logic Test was presented as a valid and relevant intelligent test used worldwide by schools and private companies. The experimenter explained that previous research showed that test scores predict academic achievement and professional success. Participants were given four minutes to complete the test. Feedback was manipulated by false statistics of success rate of other Princeton students on the test, indicating that the participants had either performed worse or better than average (see Vohs & Heatherton, 2001).

Control condition

In this condition, participants were informed that the test was part of a pilot study. Participants were told to try to work on the problems for four minutes. They were not given any information about the test nor its implications in terms of intelligence. After four minutes, they were asked what they thought about this test, but received no feedback.

Next, all participants began the study for which they believed they were originally recruited. Participants read a job announcement for a personnel manager position, described as requiring both competence and warmth qualities. Participants were also given the candidate’s résumé. The candidate was either Asian American or a working mother. Job candidates’ résumés were identical with two exceptions: The Asian American target was identified as “Jennifer Lee” and as a member of the Asian American Association; the working mother was identified as “Tiffany Taylor” and the résumé indicated that she had a child. Participants also read a passage from an excerpt of the job candidate interview. The candidate’s performance was described as average. Participants then evaluated the candidate on traits related to competence (e.g., efficient, ambitious) and warmth (e.g., friendly, warm) on a seven-point scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 7 (“extremely”). They also responded to questions evaluating the target’s suitability for the job (i.e., “I felt favorably inclined toward this person.”, “I would likely give this person serious consideration for the position in question”) using the same seven-point scale. Finally, participants completed a state self-esteem measure (Heatherton & Polivy, 1991). They were then fully debriefed and thanked for their participation.

Results

Manipulation Check: State Self-Esteem

A one-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant effect of feedback condition on self-esteem scores, F(2, 89) = 4.74, p < .02. Participants in the negative feedback condition had a lower self-esteem (M = 3.43, SD = .10) compared to those in the positive feedback condition (M = 3.70, SD = .10, p = .05) and in the control condition (M = 3.86, SD = .10, p < .004). Our self-threat manipulation was successful.

Perceived Level of Competence and Warmth

We computed scores of perceived competence and perceived warmth. The competence score was composed of the following items: intelligent, efficient, motivated, ambitious and competent (alpha = .79). The warmth score was composed of the following items: insensitive, arrogant, sincere, conceited, friendly, warm and happy; the first three items were reversed-coded (alpha = .88). Target’s perceived warmth and competence were analyzed in a 3 (feedback) × 2 (targets) × 2 (dimensions), with the last factor as within-participants. The overall three-way interaction was marginal, F(2, 86) = 2.39, p < .10. The main effect of dimension was significant, F(1, 86) = 59.89, p < .0001. No other effect was significant, Fs ≥ 2.40, ps ≥ .13. We decomposed this interaction by separately analyzing competence and warmth ratings in a 3 × 2 ANOVA with feedback and target as between-participants factors.

Perceived competence

Because Asian Americans are derogated for their lack of warmth, we did have no specific prediction for the competence score. None of the main effects were significant, Fs<1. The interaction was not significant, F(1, 86) = 2.01, p < .15.

Perceived warmth

We predicted that in comparison to positive feedback and control conditions, participants in the negative feedback condition would perceive the Asian target as less warm than the working mother.

The analysis on scores of perceived warmth did not reveal significant effects of feedback or target (Fs ≥ 1.20, ps ≥ .28). As predicted, the interaction was significant, F(1, 86) = 4.59, p < .013 (see Table 1). Simple effects revealed that the Asian target was evaluated as less warm than the working mother by participants in the negative feedback condition (M = 4.79, SD = 1.03 vs. M = 5.60, SD = .49, p < .004). In contrast, differences in perceived warmth between the Asian target and the working mother were not significant in the positive feedback condition (M = 5.09, SD = .21 vs. M = 4.80, SD = .21), and in the control condition (M = 5.10, SD = .90 vs. M = 5.05, SD = .22, F < 1), ps > .31.

Table 1.

Mean rating of job candidates’ perceived warmth and perceived competence as a function of feedback condition and type of target.

| Warmth | Competence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| negative | positive | control | negative | positive | control | ||

| Asian | M | 4.67a | 5.09 | 5.10 | 5.73 | 5.84 | 5.76 |

| SD | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| working mother | M | 5.60ab† | 4.80b | 5.05† | 5.86 | 5.36 | 5.86 |

| SD | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.18 | |

p < .01;

p < .10

Simple effects also revealed that the working mother was evaluated as warmer by participants in the negative feedback condition than those in the positive feedback condition (p < .01), and marginally warmer than those in the control condition (p < .09). Moreover, the Asian target was not evaluated as significantly less warm by participants in the negative feedback condition compared to those in the positive feedback and control conditions (ps >.14).

Consistent with our hypothesis, following a threat to their competence, participants evaluated the Asian target as less warm than the working mother. However, the Asian target was not evaluated significantly less warm in the negative feedback condition compared to non-threatening feedback conditions.

Evaluation of Suitability for the Job

We predicted that in comparison to non-threatening feedback, threatening feedback would lead participants to evaluate the Asian target as less suited for the job than the working mother target. Two questions concerned participants’ evaluation of the candidates’ suitability for the job (alpha = .75).

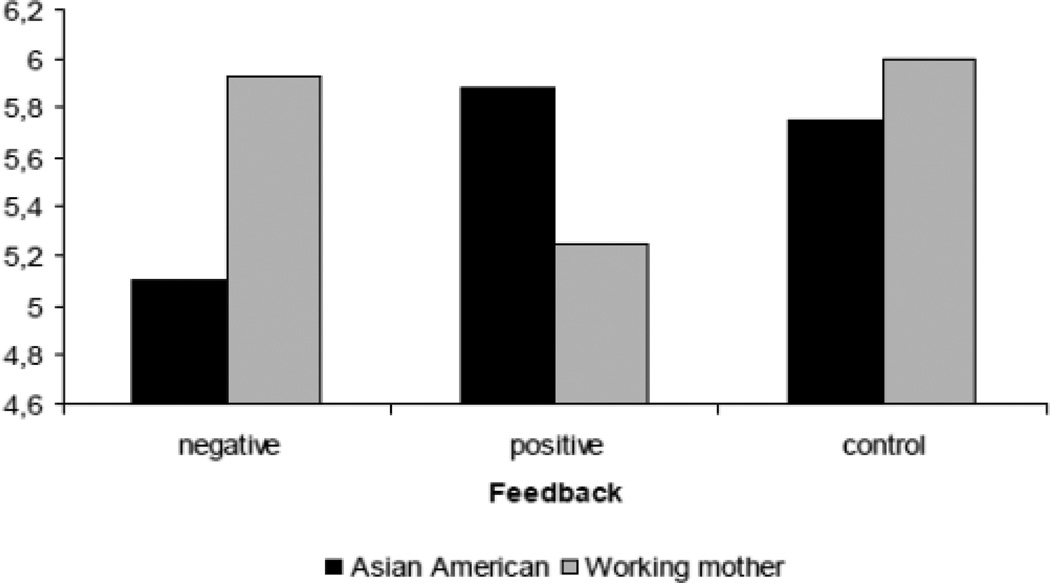

The scores of target’s perceived suitability were analyzed in a 3 (feedback) × 2 (target) ANOVA. This analysis revealed no significant effects of feedback or target (Fs ≥ 1.45, ps ≥ .25). As expected, the interaction was significant, F(1, 86) = 5.18, p < .008 (see Figure 1). Simple effects revealed that, in the negative feedback condition, participants evaluated the working mother as more suited for the job than the Asian candidate (M = 5.93, SD = .68 vs. M = 5.10, SD = .91, p < .015). In the control condition, there was no difference in the evaluation of suitability between the working mother and the Asian candidate (M = 5.75, SD = .93 vs. M = 6.00, SD = .71, F < 1). However, in the positive feedback condition, the working mother was perceived as less suitable for the job than the Asian target, (M = 5.25, SD = 1.24 vs. M = 5.88, SD = .67, p = .05).

Figure 1.

Mean rating of evaluations of job candidates’ suitability as a function of feedback condition and type of target.

Simple effects showed that the Asian target was also perceived as less suitable for the job in the negative feedback condition compared to the positive feedback and control conditions (ps < .05). However, the working mother was perceived as less suitable for the job in the positive feedback than in negative feedback and control conditions (ps < .05).

Consistent with our expectations, the Asian target was evaluated as less suited for the job than the working mother by participants who experienced threat compared to those who did not. Unexpectedly, following positive feedback, participants evaluated the working mother as less suitable for the job than the Asian candidate, compared to those in both control and negative feedback conditions.

Mediated Moderation

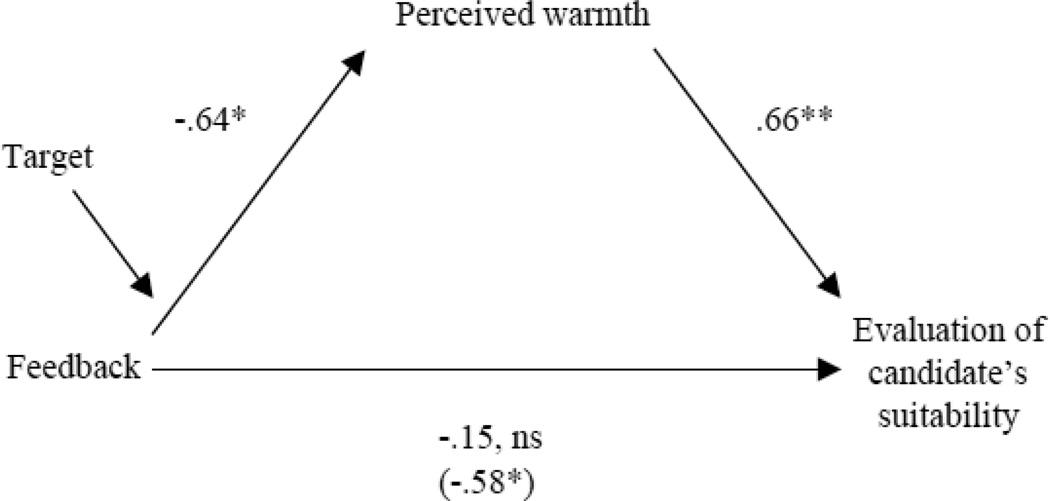

We expected the level of perceived warmth to mediate the differences observed in the evaluation of job candidates’ suitability across feedback conditions. We conducted a mediated moderation analysis (Muller, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2005). Firstly, we showed that the interaction between feedback condition (i.e. contrast comparing threatening to non-threatening feedbacks) and target type was a good predictor of the evaluation of the candidates’ suitability for the job, B = −.63, t(87) = −2.12, p < .021. Secondly, this same interaction was also a good predictor of perceived warmth, B = −.72, t(87) = −2.91, p < .01. Finally, when controlling for perceived warmth (i.e. the mediator), the analysis showed that perceived warmth predicts the evaluation of suitability for the job, B = .66, t(86) = 6.83, p < .0001, indicating a positive relation between warmth and the judged suitability. Additionally, the interaction between the feedback condition and the type of target no longer predicted the evaluation of candidates’ suitability for the job, B = −.15, ns, indicating a full mediation (see Figure 2)2. The Sobel test confirmed the presence of a mediated moderation (z = −2.69, p < .008).

Figure 2.

Mediated moderation with feedback condition and type of target as IVs, perceived warmth as mediator and evaluation of candidate’s suitability as DV.

*p < .05, ** p < .01

These above findings suggest that perceived warmth predicted the evaluation of job candidates’ suitability, consistent with Lin et al. (2005).

Discussion

The present study extends previous research by incorporating Stereotype Content Model (SCM) in the link between self-threat and negative evaluation of stereotyped targets. The findings suggest that it is necessary to take into account the target group’s stereotype content when examining this link. Our findings reinforce the idea that following a threat to one’s competence, the evaluation of a target will differ according to the target group’s stereotype related to the dimensions competence and warmth as proposed by the Stereotype Content Model (SCM). In particular, a threat on the competence dimension leads to derogation of targets stereotyped as competent but lack warmth.

Our findings indeed support the idea that following a threat on a dimension, people derogate targets stereotyped as possessing the threatened attribute. Thus, participants who previously experienced a threat to their competence subsequently evaluated the Asian target, stereotyped as competent but not warm, as less suited for the job than the working mother (stereotyped as warm but incompetent). Furthermore, the Asian candidate was evaluated as less suited for the job by participants who experienced a threat compared to those who did not. Perceived warmth was the factor that mediates participants’ evaluation of the target’s suitability for the job. That is, the more the target candidate was perceived as warm, the more she was evaluated as well-suited for the job. Consequently, following a threat to their competence, participants evaluated the Asian target as less suited for the job because of her perceived lack of warmth.

Our findings can be directly linked to research on self-affirmation. It has shown that, to undermine self-threat, people use compensation strategy by affirming themselves on another important dimension. People may self-affirm their social skills, another important base for individuals’ self-concept and self-esteem (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001; Tafarodi & Swann, 1995), when they experience a threat to their competence (Brown & Smart, 1991). Thus, following a threat on competence, warmth would become more relevant for the self and for the evaluation of others, leading to a relatively more negative evaluation of targets perceived as competent and cold. Our findings thus complete previous research on self-affirmation by identifying the dimension on which evaluation of others would be made, using the SCM, in the case of threat or ‘anti’ self-affirmation.

In line with self-affirmation idea, we found that positive feedback led participants to evaluate the working mother as less suitable for the job, suggesting that the dimension of competence was used in the evaluation as working mothers are seen as incompetent but warm. In contrast, a threat may lead to the use of another dimension than that on which threat is experienced. This other dimension can be that related to the negative aspect the target’s stereotype as predicted by the SCM or another dimension as dictated by the particular context of evaluation. As an example, Belgian students emphasized the warmth dimension in their evaluation of the French, a group that is perceived by these participants as threatening their linguistic competence dimension (Provost, Yzerbyt, Corneille, Désert, & Francard, 2003). This perceived lack of warmth allowed the Belgian participants to evaluate the French negatively, presumably in the service of a positive self-maintenance (Yzerbyt, Provost, & Corneille, 2004).

The findings of Fein and Spencer (study 2, 1997) which show that stereotyping of gay men increased following a threat to the self (induced via negative feedback) can be seen as providing a more direct our idea (that threat on competence can lead people to evoke warmth as a basis of evaluation). Though framed in term of increased stereotyping, the greater use of gay stereotypical traits (such as sensitive, considerate) implied that the (gay) target was evaluated as higher on warm dimension by threatened than by non-threatened participants. This observation is also consistent with the observed increase in perceived warmth of the working mother target by participants in our study, following negative (threatening) feedback on their competence.

The present results thus confirm that idea that the target’s perceived warmth mediates her subsequent derogation and relatively more negative evaluation of her suitability for the job. However, the Asian target was not perceived as less warm in the threatening than in non-threatening conditions. Modern racism could be evoked as a possible explanation for this observation (McConahay, 1986; Fiske, 1998): People are motivated to appear non-prejudiced and will not express negative stereotypes explicitly. Thus, target’s derogation or negative evaluation should be more likely to appear on relatively more indirect measures such as the evaluation of target’s suitability for the job rather than the more direct measures of target’s characteristics related to the stereotype. This allowed participants to satisfy not only their motivation to restore a threatened self-esteem, but also to avoid appearing prejudiced which is another important motivation to consider when dealing with student participants (Livingston & Sinclair, in press; Plant & Devine, 1998). Past studies have indeed shown that individuals may attempt to avoid appearing prejudiced when evaluating a target belonging to a stereotyped minority group as it is, among others, in contradiction with their egalitarian values (see Dovidio, Gaertner, Anastasio & Sanitioso, 1992).

In the present article, we presented findings from a study suggesting that stereotype content as specified by SCM contributes to refining our understanding between threat and stereotyped evaluation of a target. However, the target choice constitutes a main limit of the present study. Indeed, contrary to the Asian target, the working mother belonged to the same ethnic group as our participants. Thus these two targets did not present an asymmetry on the competent and warmth dimensions only, but also on the ingroup-outgroup dimension. Our choice for these two targets was guided by the existing literature on SCM. Indeed, it has been repeatedly demonstrated that the Asian group is perceived as consistently competent but not warm (Fiske, et al., 2002; Lin et al., 2005). Moreover, Cuddy et al. (2004) showed that working mothers, in an organizational context, are consistently perceived as less competent than warm. The consistency in perceived warmth and competence represents an important criterion that would allow us to examine use of or non use of the two dimensions identified as basic in group stereotyping according to the SCM. Thus, our target choice represents a compromise and presents some detrimental aspects, but less than if we had used another ethnic out-group that has been examined in the SCM perspective that includes many subtypes that differ in their perceived competence and warmth (e.g., African-Americans; see Fiske et al., 2002). Of course, future studies will necessarily include targets belonging to ethnic outgroups to corroborate the present finding.

To conclude, consistent with Fein and Spencer (1997), following self-threat, negative stereotype will justify the derogation of the target. However, as shown here, target derogation depends on target’s group stereotype content. Indeed, threatening individuals’ competence led to the derogation of targets stereotyped positively on the threatened dimension (e.g., competence) and negatively on the alternative dimension (e.g. warmth).

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Stéphanie Demoulin and Mike Friedman for their helpful comments on earlier version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The regression equation contained target condition, a contrast comparing negative to non-threatening feedback and its interaction with target type, the residual contrast comparing the two non-threatening feedback and its interaction with target condition.

Consistent with previous results, the interaction between the residual contrast and target condition was not a good predictor of the target’s perceived warmth, B = .24, t<1, but a marginally good predictor of the target’s suitability, B = .88, t(87) = 1.98, p < .06. When controlling for warmth, the latter interaction remained marginal, B = .72, t(86) = 1.97, p < .06.

Contributor Information

Julie Collange, Université Paris Descartes.

Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University

Rasyid Sanitioso, Université Paris Descartes.

References

- Baumeister RF, Tice DM. Self-esteem and responses to success and failure: Subsequent performance and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality. 1985;53:450–467. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Dutton KA. The thrill of victory, the complexity of defeat: Self-esteem and people's emotional reactions to success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:712–722. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Smart SA. The self and social conduct: Linking self-representations to prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:368–375. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell CA, Neuberg SL. Different emotional reactions to different groups: A sociofunctional threat-based approach to "prejudice". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:770–789. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Thompson LL, McGraw KM, Ingerman C. Downward comparison, prejudice, and evaluation of others: Effects of self-esteem and threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:907–916. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Wolfe CT. Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review. 2001;108:593–623. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. When Professionals Become Mothers, Warmth Doesn't Cut the Ice. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;60:701–718. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Kwan VSY, Glick P, Demoulin S, Leyens JPh, Bond MH, et al. Stereotype content model holds across cultures: Universal similarities and some differences. British Journal of Social Psychology. doi: 10.1348/014466608X314935. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Anastasio PA, Sanitioso R. Cognitive and motivational bases of bias: Implications of aversive racism for attitudes toward Hispanics. In: Knouse SB, Rosenfeld P, Culbertson AL, editors. Hispanics in the workplace. London: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fein S, Spencer SJ. Prejudice as self-image maintenance: Affirming the self through derogating others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th ed. vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 357–411. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, .Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Xu J, Cuddy AJC, Glick P. (Dis)respecting versus (dis)liking: Status and interdependence predict ambivalent stereotypes of competence and warmth. Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP, Fiedler K. Us and Them: Mood effects on intergroup discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Polivy J. Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:895–910. [Google Scholar]

- Kunda Z, Spencer SJ. When do stereotypes come to mind and when do they color judgment? A goal-based theoretical framework for stereotype activation and application. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:522–544. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MH, Kwan VSY, Cheung A, Fiske ST. Stereotype Content Model explains prejudice for an envied outgroup: Scale of anti-Asian American stereotypes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:34–47. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston SD, Sinclair L. Taking the watchdog off its leash: Personal prejudices and situational motivations jointly predict derogation of a stigmatized source. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005 doi: 10.1177/0146167207310028. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConahay JB. Modern Racism, ambivalence, and the modern racism scale. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, discrimination, racism. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 91–125. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlin DB, Blascovich J. On the Remote Associates Test (RAT) as an alternative to illusory performance feedback: A methodological note. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1984;5:223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Mednick SA. The Remote Associates Test. Journal of Creative Behavior. 1968;2:213–214. [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt V. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:852–863. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant EA, Devine PG. Internal and external motivation to respond without prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:811–832. doi: 10.1177/0146167205275304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost V, Yzerbyt VY, Corneille O, Désert M, Francard M. Stigmatisation sociale et comportements linguistiques: Le lexique menacé [Social stigmatization and linguistic behaviors: The lexicon threatened.] Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale. 2003;16:177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RH. Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons. In: Suls J, Wheeler L, editors. Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tafarodi RW, Swann WBJ. Self-liking and self-competence as dimensions of global self-esteem: Initial validation of a measure. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65:322–342. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6502_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Heatherton TF. Self-esteem and threats to self: Implications for self-construals and interpersonal perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1103–1118. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.6.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yzerbyt V, Provost V, Corneille O. Not competent but warm… Really? Compensatory stereotypes in the French-speaking world. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2005;8:291–308. [Google Scholar]