Abstract

Purpose

To address the translational research question regarding the optimal intervention “dose” to produce the most cost effective rate of weight loss, we conducted the Drop It At Last (DIAL) study.

Design

DIAL is a 6 month pilot randomized trial to examine the efficacy of phone-based weight loss programs with varying levels of treatment contact (10 vs 20 sessions) in comparison to self-directed treatment.

Setting

Participants were recruited from the community via mailings and advertisement.

Subjects

Participants were 63 adults with a body mass index between 30–39 kg/m2.

Intervention

Participants received a standard set of print materials and were randomized to either: 1) self-directed; 2) 10 phone coaching sessions; or 3) 20 phone coaching sessions.

Measures

Measured height and weight, psychosocial and weight-related self-monitoring measures were collected at baseline and follow-up.

Analysis

General linear models were used to examine 6 month treatment group differences in weight loss, psychosocial, and behavioral measures.

Results

Weight losses were −2.3, −3.2, and −4.9 kg in the self-directed, 10-, and 20-session groups, respectively (p < .21). Participants who completed ten or more sessions lost more weight (−5.1 kg) compared to those completed four or fewer sessions (−0.3 kg, p < .04).

Conclusion

Phone-based weight loss program participation is associated with modest weight loss. The optimal “dose” and timing of intervention warrants further study.

Keywords: obesity, weight loss, behavior therapy, randomized clinical trial

Indexing Key Words: 1. Manuscript format: research; 2. Research purpose: intervention testing/program evaluation; 3. Study design: randomized trial; 4. Outcome measure: biometric; 5. Setting: local community; 6. Health focus: weight control; 7. Strategy: skill building/behavior change; 8. Target population: adults; 9. Target population circumstances: all education/income levels, all race/ethnicity, metropolitan area

Purpose

Behavior therapy (BT) for weight loss has been developed over the last 30 years and entails multiple counseling sessions over time between patients and health professionals with expertise in diet, exercise and behavioral compliance strategies.(1, 2) A number of variations in content and format have been explored, but the one now considered the “gold standard” is that used in large weight loss trials, like the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and ongoing Look AHEAD studies (3, 4) Treatment entails weekly face-to-face visits for up to 6 months with contacts at least monthly for an indefinite period to support weight loss maintenance. Participants are instructed to keep records of energy intake and expenditure, and to strive toward specific energy intake and expenditure goals. BT also includes a variety of compliance enhancement strategies, such as use of meal substitutes, stimulus control, social support and mood management. The effect of BT on body weight in these tightly controlled trials, although not universally effective, is clinically significant weight loss that is consistent in magnitude and time course across clinics, different types of patients and ethnic groups.(1, 2) Weight losses of 8 to 10 % of body weight are achieved over 6 months or so in the best of these treatments. Weight is then slowly regained over several years of follow up with significant clinical benefits seen for at least 4 to 5 years.(1)

Translating the success of research like the DPP into programs that have the potential for large population reach is challenging. A major barrier is the accessibility of clinic-based weight loss programs. Less than 50% of overweight women and 20% of overweight men have ever participated in a formal weight-control program, (5, 6) and about two-thirds of these are low-cost commercial programs with very high dropout rates (i.e., average duration of participation is about 2 weeks).(7, 8) Although reasons for these low participation rates have not been carefully examined, it seems likely that high monetary and behavioral costs (i.e. attendance at weekly meetings) are key factors. For maximal population impact, weight management systems are needed that are effective, that are less costly than traditional high intensity clinical approaches,(9) that are attractive to a broad spectrum of people, and that can successfully engage people over time to counteract the tendency toward lagging motivation and weight regain that typically occurs in obesity treatment programs.

Research designed to reduce the cost of obesity treatments has a long history, the main focus of which has been to reduce the amount of therapist time. These efforts have examined weight loss by mail,(10–13) phone,(10, 11, 13–15), and recently the Internet.(16–20) The overall outcome has been that removing interactive human contact from BT dramatically reduces its effectiveness and making non-clinic contacts as effective as clinic visits can cost as much or more than traditional group clinic sessions. In our own health system based obesity treatment trial, Weigh to Be (WTB), we addressed the cost issue by shortening the standard BT format of 34 (DPP) to 56 (Look AHEAD) contacts over 2 years to 10, and delivered the intervention by phone or mail rather than face-to-face. In addition to decreases in session numbers, intervention message content was significantly modified to accommodate the then prevailing philosophy of the health care delivery group and clinical weight loss community about appropriate weight control messages. The resultant messages placed less emphasis on setting challenging behavioral goals and on self-monitoring of diet, activity and body weight and were much less intensive than those used in “gold standard” BT. Unfortunately, intervention length, delivery mode, and message intensity modifications reduced treatment efficacy so that weight losses were substantially lower than with standard BT and the percentage of patients achieving clinically significant weight losses at 24 months was too small to make a strong case for the treatment cost effectiveness.(21) In effect, our efforts to make treatment more economical reduced efficacy below a level of practical utility.

A critical question for translational weight loss research is determining the optimal “dose” of intervention to produce the most cost effective rate of clinically significant weight loss. To address this question, we conducted a pilot randomized trial, the Drop It At Last (DIAL) study, to examine the efficacy of two phone-based weight loss programs which were similar with respect to content, but were of varying levels of treatment contact (10 sessions vs 20 sessions) in comparison to a self-directed treatment group receiving a similar set of print materials. The present report describes the 6 month weight and behavioral outcomes of the DIAL study.

Methods

Design

DIAL (Drop It At Last) was a 6-month randomized trial investigating the effectiveness of a 10 Session and 20 Session telephone-based weight loss counseling intervention compared to a self-directed weight-loss program. The study was conducted at the Epidemiology Clinical Research Center at the University of Minnesota. Study recruitment began in March 2007 and data collection was completed in November 2007.

Sample

Participant recruitment was conducted over a period of 12 weeks. Postcards were mailed to University of Minnesota employees using campus address mailing lists. In addition, advertisements were placed in three metropolitan neighborhood newspapers. Interested individuals were instructed to call or email a DIAL staff member for information about the study.

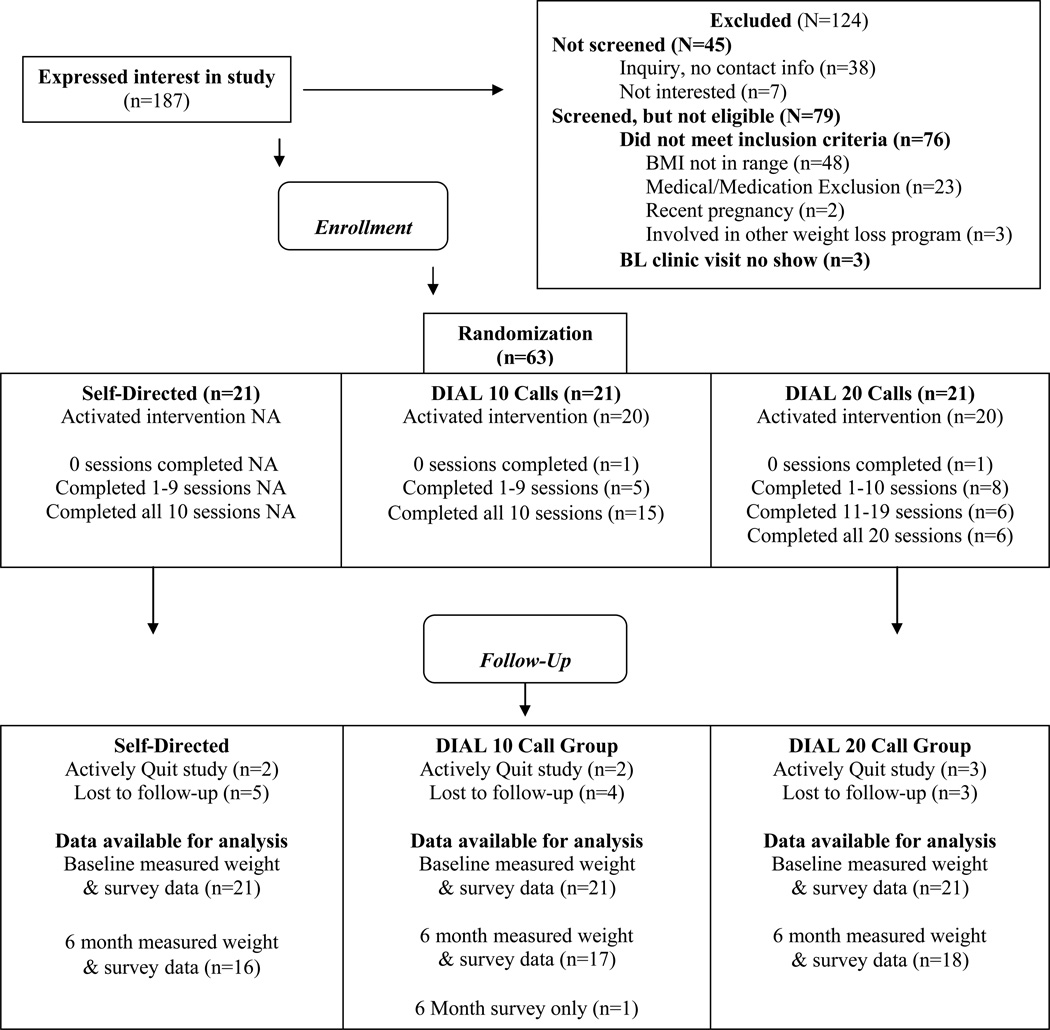

Prospective participants were screened during the informational telephone call. Primary eligibility criteria included age 18 years or older and body mass index (BMI) between 30–39 kg/m2. In addition, eligible individuals were free of serious physical and psychological health conditions, not currently participating in an organized weight loss program or research study, not pregnant within the last 6 months or currently breastfeeding, and had to live within 50 miles of the clinic center. Figure 1 depicts the CONSORT diagram for trial. Of the 187 individuals who made an inquiry about the study, 142 were screened, 76 did not meet inclusion criteria, primarily due to having a BMI outside of the eligibility window or a serious medical condition, and 66 satisfied eligibility criteria.

Figure 1.

Modified CONSORT Diagram for the DIAL Study

Eligible individuals interested in participating in the study were invited to attend an orientation clinic visit where their heights and weights were measured using a wall-mounted ruler and calibrated digital scale to confirm eligibility. The study was then described to them again in detail by DIAL staff members and informed consent was documented by signature in accordance with the University of Minnesota Human Subjects Review Committee. Among the 66 eligible individuals, 63 completed the consent process and enrolled in the study. After providing consent, participants completed a series of questionnaires, described below. Upon completion of the baseline orientation clinic visit, participants were randomized to one of three conditions: 10-session phone intervention, 20-session phone intervention, or self-directed intervention.

Measures

At baseline and 6-months, participants attended clinic visits at which height and weight was measured and self-report measures were collected including:

Demographic characteristics

Measures at baseline included age (years), sex (male/female), race (White, Black, Asian, Other), education (<high school, high school only, some college/tech degree, college degree/some graduate, graduate degree), current employment (yes/no), job type (professional, clerical, labor, other), and marital status (married/living together, separated/divorced, widowed, never married).

Smoking status

Ever smoking status (yes/no) and current smoking status (yes/no), measured at baseline.

Anthropometric characteristics

Height and weight was measured at baseline and 6-month clinic visits using a wall-mounted ruler and calibrated digital scale. Body mass index (BMI) was computed from weight and height (kg/m2) for each time-point.

Energy Expenditure

The Paffenbarger Activity Questionnaire(22, 23) (was completed at baseline and 6-month follow-up to estimate calories expended per week in overall leisure-time activity and in activities of various intensity.

Psychosocial characteristics

Measures at baseline and 6-month follow-up included the Body Satisfaction Questionnaire-16(24) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).(25) The BDI is a self-report questionnaire which assesses depressive symptoms such as feelings of hopelessness, irritability, guilt, and fatigue. The BSQ-16 is a self-report measure designed to assess an individual’s fear of gaining weight, feelings of low self-esteem due to their appearance, their desire to lose weight, and body dissatisfaction. Higher summary scores on the questionnaires indicate greater depressive symptomatology (score range 0–63) and greater body shape dissatisfaction (score range 34–204), respectively.

Self-monitoring behaviors

Participants reported self-weighing frequency as never, about once a year or less, every couple of months, every month, every week, every day, and more than once a day. In addition, participants rated the frequency (i.e. never, rarely, sometimes, often, very often) they engaged in a variety of other weight management self-monitoring behaviors, including writing down the amount of calories consumed, writing down the amount and type of food eaten and exercise done, and planning meals and exercise for weight control.

Intervention

After randomization, participants were sent a letter notifying them of their assignment. In addition to the notification letter, all participants were sent an instructional manual, a pedometer, and log booklets for monitoring daily weight, food intake, and physical activity. After 1 week of mailing out notification letters and materials, participants in the telephone intervention conditions were contacted by their respective telephone counselor to initiate treatment. Self-directed participants received the same instructional manual, pedometer, and log booklets, but were not contacted by DIAL staff members other than to complete follow-up measures, described below.

Participants in the 10-session telephone condition were contacted by their telephone counselors on a weekly-basis on a day and time agreed upon at the end of each session. Telephone sessions were approximately 10–20 minutes in duration, and were designed to be completed in sequence. During each call, participants reported on progress and barriers of weight loss experienced since the last session. The counselor then focused on a particular behavioral weight-loss strategy which was outlined in the instructional manual, and discussed with the participant ways to implement such behavioral changes into his or her lifestyle. Session topics included nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral change techniques. Participants were encouraged to monitor calorie intake and expenditure, as well as body weight, on a daily basis and record this information using the log booklets provided to them.

The 20-session intervention was designed to differ from the 10-week intervention only in number of calls. The 10-session instructional manual was divided in such a way to accommodate 20 sessions, and telephone counselors conducted sessions in accordance with the 20-week instructional manual.

Analysis

The primary outcomes examined in this study were changes in body weight from baseline to 6 months. Data analyses were done using the general linear models programs of SAS (Version 8.7). Group differences in 6 month change in weight, percent achieving a minimum of 5% weight loss, and weight-related psychological and behavioral characteristics were examined controlling for baseline weight.

Secondarily, weight and weight-related behavior change was also examined as a function of treatment participation level with participants in the 10- and 20-session phone groups categorized into one of three groups: 0–4 phone calls, 5–9 phone calls, or ≥ 10 phone calls for these analyses. These cut-points were chosen to represent low, medium, and high call completion rates.

All analyses used an intent-to-treat approach by which no change in body weight or weight-related behavioral and psychological characteristics were imputed for individuals who did not complete the 6 month clinic visit. Similar sets of analyses using study completers only yielded similar results and are not presented here.

Results

Sixty-three participants were randomized to the three groups. A CONSORT diagram to illustrate study flow diagram can be seen in Figure 1. There were no significant between group differences on any of the baseline measures including demographic, weight, psychological and behavioral characteristics (see Table 1). Participants who were available for the 6-month follow-up did not significantly differ across any of the baseline measures relative to participants who were unavailable for the 6-month follow-up (data not shown).

Table 1.

DIAL Participant Characteristics at Baseline

| Frequency (column %) and mean values ±SE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Self-directed | 10 Call | 20 Call | p | |

| N | 63 | 21 (33.3) | 21 (33.3) | 21 (33.3) | |

| Mean age | 49.5 ±1.4 | 52.3 ±2.5 | 46.6 ±2.5 | 49.5 ±2.5 | 0.27 |

| Sex | 0.47 | ||||

| Female (%) | 79.4 | 81.0 | 85.7 | 71.4 | |

| Race | 0.26 | ||||

| White (%) | 82.5 | 95.2 | 76.2 | 76.2 | |

| Education | 0.19 | ||||

| College and/or | |||||

| Graduate degree (%) | 57.8 | 47.6 | 54.6 | 71.4 | |

| Currently employed | 0.75 | ||||

| Yes (%) | 89.1 | 95.2 | 81.8 | 90.5 | |

| Job Type | 0.93 | ||||

| Professional (%) | 45.6 | 45.0 | 44.4 | 47.4 | |

| Clerical, labor, other (%) | 54.4 | 55.0 | 55.6 | 52.6 | |

| Marital Status | 0.43 | ||||

| Married/Living together (%) | 54.7 | 61.9 | 50.0 | 52.4 | |

| Mean weight (kg) | 95.3 ±1.5 | 95.5 ±2.7 | 93.6 ±2.7 | 96.7 ±2.7 | 0.71 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 34.2 ±0.5 | 34.9 ±0.8 | 33.9 ±0.8 | 33.9 ±0.8 | 0.59 |

| Phy. activity (kcal/wk) | 1186.4 (164.3) | 1048.4 (285.9) | 1463.3 (285.9) | 1047.6 (285.9) | 0.50 |

| BDI | 6.6 ±0.6 | 6.1 ±1.0 | 7.7 ±1.0 | 5.8 ±1.0 | 0.38 |

| BSQ-16 | 118.0 ±4.2 | 122.2 ±7.7 | 119.1 ±7.3 | 113.0 ±7.3 | 0.67 |

| Binge Eating | |||||

| Any binge (%) | 34.9 | 28.6 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 0.75 |

| Probable binge (%) | 14.3 | 4.8 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 0.37 |

| Self-weighing frequency | 0.77 | ||||

| Daily (%) | 15.9 | 14.3 | 23.8 | 9.5 | |

| Weekly (%) | 38.1 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 38.1 | |

| Every month or less (%) | 46.0 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 52.4 | |

| Self-monitoring | |||||

| Write amount of food Never/rarely (%) | 77.6 (n=45) | 79.0 (n=15) | 84.2 (n=16) | 70.0 (n=14) | 0.60 |

| Write calories Never/rarely (%) | 86.2 (n=50) | 84.2 (n=16) | 89.5 (n=17) | 85.0 (n=17) | 0.89 |

| Write exercise Never/rarely (%) | 77.6 (n=45) | 68.4 (n=13) | 84.2 (n=16) | 80.0 (n=16) | 0.48 |

| Plan meals Never/rarely (%) | 48.3 (n=28) | 57.9 (n=11) | 42.1 (n=8) | 45.00 (n=9) | 0.58 |

| Plan exercise Never/rarely (%) | 46.6 (n=27) | 52.6 (n=10) | 42.1 (n=8) | 45.00 (n=9) | 0.80 |

Table 2 presents weight-change and weight-related psychological and behavioral outcomes at 6-month follow-up. On average, participants across all study conditions lost weight (i.e., weight loss in each group was significantly different from 0). Although no statistically significant treatment group differences in 6 month weight change were observed, weight loss trends were in the expected direction with participants in the 20 session treatment group losing twice as much weight, on average, compared to participants in the self-directed group (Cohen’s d=.49). Similarly, although not statistically significant, twice as many participants in the 20 session group lost at least five percent of their body weight in comparison to participants in the self-directed group. Examination of 6 month change in weight related behavioral and psychological characteristics by treatment group shows that participants in the 20 session group were marginally more likely to report decreases in depressive symptoms and body shape dissatisfaction, and marginally more likely to report increases in the frequency of self-weighing and recording their exercise.

Table 2.

Six month study outcomes by treatment group status

| Column % (n) and mean values ±SE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Group | Self-Directed | 10 Call | 20 Call | p |

| Weight change (kg) | −2.3 ±1.1 | −3.2 ±1.1 | −4.9 ±1.1 | 0.21 |

| 5% Weight Loss | 19.0 (n=4) | 33.3 (n=7) | 42.9 (n=9) | 0.25 |

| Physical activity change (kcal/wk) | 116.0 ±267.0 | 18.9 ±268.6 | 564.3 ±267.0 | 0.31 |

| BDI change* | −0.3 ±0.8 | −1.8 ±0.8 | −2.6 ±0.8 | 0.10 |

| BSQ-16 change** | −10.3 ±5.4 | −9.9 ±5.1 | −24.3 ±5.2 | 0.09 |

| Self-weighing frequency | ||||

| Increase self-weighing | 33.3 (n=7) | 23.8 (n=5) | 57.1 (n=12) | 0.07 |

| Self-monitoring frequency | ||||

| Increase write amount of food | 26.3 (n=5) | 33.3 (n=6) | 55.0 (n=11) | 0.16 |

| Increase write calories | 36.8 (n=7) | 38.9 (n=7) | 65.0 (n=13) | 0.15 |

| Increase write exercise | 31.6 (n=6) | 42.1 (n=8) | 70.0 (n=14) | 0.05 |

| Increase plan meals | 42.1 (n=8) | 33.3 (n=6) | 50.0 (n=10) | 0.58 |

| Increase plan exercise | 42.1 (n=8) | 31.6 (n=6) | 50.0 (n=10) | 0.50 |

NOTE: Analyses with continuous outcomes are adjusted for baseline values of dependent variables. Missing values at 6 months were imputed with baseline values, assuming no change.

Table 3 presents 6 month study outcomes as a function of treatment participation for the two phone intervention groups. The 20- and 10-session groups completed a median of 19 and 10 telephone counseling calls, respectively. Examination of the relationship between level of treatment participation and weight outcomes showed that among the combined group of 10- and 20-session participants, more counseling calls were associated with greater weight loss and a higher frequency of engaging in weight-related self-monitoring behaviors including planning meals and recording amounts of food eaten and exercise patterns.

Table 3.

Six month study outcomes by intervention exposure

| Column % (n) and mean values ±SE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Completion | 0–4 Phone calls (n=7) | 5–9 Phone calls (n=5) | 10+ Phone calls (n=30) | p |

| Weight Change (kg)* | −0.3a ±1.7 | −2.5a,b ±2.0 | −5.1b ±0.8 | 0.04 |

| 5% Weight Loss | 0 (n=0) | 20.0 (n=1) | 50.0 (n=15) | 0.03 |

| Self-weighing frequency | ||||

| Increase self-weighing | 0 (n=0) | 80.0 (n=4) | 43.3 (n=13) | 0.02 |

| Self-monitoring frequency | ||||

| Increase write amount of food | 14.3 (n=1) | 0 (n=0) | 59.3 (n=16) | 0.02 |

| Increase write calories | 14.3 (n=1) | 50.0 (n=2) | 63.0 (n=17) | 0.07 |

| Increase write exercise | 14.3 (n=1) | 75.0 (n=3) | 64.3 (n=18) | 0.04 |

| Increase plan meals | 0 (n=0) | 75.0 (n=3) | 48.2 (n=13) | 0.03 |

| Increase plan exercise | 14.3 (n=1) | 50.0 (n=2) | 46.4 (n=13) | 0.28 |

NOTE: Analysis adjusted for baseline weight. Missing values at 6 months were imputed with baseline values, assuming no change. Superscripts denote significant differences for p-values at the 0.05 level.

Discussion

The goals of the Drop It At Last (DIAL) pilot study were (1) to provide preliminary data to address the critical question for translational weight loss research of determining the optimal “dose” of intervention to produces the most cost effective rate of clinically significant weight loss, and (2) to utilize phone coaching as the intervention delivery mechanism to address time and cost barriers associated with “gold standard” intensive behavioral weight loss programs. To accomplish these goals, we successfully recruited 63 obese adults and randomized them to either a self-directed, materials only group, a 10 phone session group, or a 20 phone session group. Although the small sample size for this pilot study likely contributed to the lack of statistically significant weight loss differences between groups, results showed that participants in the 20 session phone group lost twice as much weight and were twice as likely as participants in the self-directed group to lose a minimum of five percent of their body weight. A precise characterization of the relationship between the number of phone counseling sessions and weight loss could not be ascertained, but the findings clearly indicated that a greater number of completed phone sessions was associated with significantly greater weight loss.

The magnitude of the weight losses achieved by participants in the phone treatment arms of the DIAL study, while more modest in comparison to intensive in-person treatment approaches, are at least comparable to or more favorable than other non-face-to-face alternative delivery modes(16, 18, 26), including our own prior work.(10, 11) For example, 33% and 43% of participants in the DIAL 10 and 20 session phone groups respectively, lost at least 5% of their body weight at 6 months in comparison to 24% of phone group participants in our previous trial. We suspect this was at least partially due to stronger intervention messaging around eating and activity goals, as well as the offering of more phone sessions, in the DIAL pilot trial relative to the Weigh to be trial.

A program of systematic research examining the effects of different ways of formatting behavioral therapy for obesity could be a valuable guide for health care providers trying to determine how to better manage obesity in their patient populations. A research strategy of examining the effectiveness of distributing equal treatment resources to patient populations with fixed content but differing numbers of treatment sessions per treated patient in randomized controlled trials shows promise for establishing the optimal “dose” of intervention that produces the most cost effective rate of clinically significant weight loss. An additional system level study design might compare the same number of treatment contacts delivered in different temporal sequences, e.g. weekly, every second week and monthly. Because a significant proportion of individuals who complete weight loss programs do not achieve clinically significant weight loss, alternative strategies for either augmenting treatment to increase efficacy or encouraging participants to take a break and restart weight loss treatment at a later time should be considered. All system studies would benefit additionally from incorporating procedures designed to provide an empirical basis for estimating the percentage of people in need who can be reached with a treatment option and at what cost.

SO WHAT?

What is already known on this topic?

Translating the success of intensive behavioral weight loss interventions into cost-effective programs is a critical need. Cost reduction efforts have included reducing treatment length and/or utilizing alternative delivery methods (e.g., phone, internet). Removing face-to-face contact and decreasing the amount of interactive human contact reduces treatment effectiveness, however, systematic research to examine the optimal “dose” of treatment delivered via alternative methods is lacking.

What does this article add?

This pilot study examined the efficacy of two phone-based weight loss programs of varying treatment levels (10 sessions vs. 20 sessions) in comparison to a self-directed treatment group. This study showed that phone-based weight loss programs are associated with modest weight loss; those who completed at least 10 sessions lost the most weight.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

Phone-based weight loss programs show promise, but further research to explore the optimal intervention timing and dose as well as creative strategies to enhance social support offered through such interventions is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project described was supported by Grant Number P30 DK050456

References

- 1.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, Stunkard AJ, Wilson GT, Wing RR, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19((1 Suppl)):5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2226–2238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Bright R, Clark JM, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.French SA, Jeffery RW. Consequences of dieting to lose weight: effects on physical and mental health. Health Psychol. 1994;13(3):195–212. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French SA, Jeffery RW, Murray D. Is dieting good for you? Prevalence, duration and associated weight and behaviour changes for specific weight loss strategies over four years in US adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(3):320–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeffery RW, Folsom AR, Luepker RV, Jacobs DR, Jr, Gillum RF, Taylor HL, et al. Prevalence of overweight and weight loss behavior in a metropolitan adult population: the Minnesota Heart Survey experience. Am J Public Health. 1984;74(4):349–352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volkmar FR, Stunkard AJ, Woolston J, Bailey RA. High attrition rates in commercial weight reduction programs. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141(4):426–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernan WH, Brandle M, Zhang P, Williamson DF, Matulik MJ, Ratner RE, et al. Costs associated with the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(1):36–47. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, Pronk NP, Boucher JL, Hanson A, Boyle R, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: weigh-to-be 2-year outcomes. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30(10):1565–1573. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeffery RW, Sherwood NE, Brelje K, Pronk NP, Boyle R, Boucher JL, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting: Weigh-To-Be one-year outcomes. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(12):1584–1592. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeffery RW, Hellerstedt WL, Schmid TL. Correspondence programs for smoking cessation and weight control: a comparison of two strategies in the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Health Psychol. 1990;9(5):585–598. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.5.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boutelle KN, Dubbert P, Vander Weg M. A pilot study evaluating a minimal contact telephone and mail weight management intervention for primary care patients. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(1):e1–e5. doi: 10.1007/BF03354659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hellerstedt WL, Jeffery RW. The effects of a telephone-based intervention on weight loss. Am J Health Promot. 1997;11(3):177–182. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindstrom LL, Balch P, Reese S. In person versus telephone treatment for obesity. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1976;7:367–369. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. Jama. 2001;285(9):1172–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. A randomized trial comparing human e-mail counseling, computer-automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an Internet weight loss program. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1620–1625. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polzien KM, Jakicic JM, Tate DF, Otto AD. The efficacy of a technology-based system in a short-term behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(4):825–830. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvey-Berino J, Pintauro SJ, Gold EC. The feasibility of using Internet support for the maintenance of weight loss. Behav Modif. 2002;26(1):103–116. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026001006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold BC, Burke S, Pintauro S, Buzzell P, Harvey-Berino J. Weight loss on the web: A pilot study comparing a structured behavioral intervention to a commercial program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(1):155–164. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherwood N, Jeffery R, Pronk N, Boucher J, Hanson A, Boyle R, et al. Mail and phone interventions for weight loss in a managed-care setting:weigh-to-be 2-year outcomes. International Journal of Obesity. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803295. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paffenbarger R, Hyde R, Wing A, Lee I-M, Jung D, Kampert J. The Association of Changes in Physical-Activity Level and Other Lifestyle Characteristics with Mortality among Men. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(8):538–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paffenbarger R, Wing A, Hyde R. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108:161–175. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans C, Dolan B. Body Shape Questionnaire: derivation of shortened "alternate forms". Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13(3):315–321. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199304)13:3<315::aid-eat2260130310>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter CM, Peterson AL, Alvarez LM, Poston WC, Brundige AR, Haddock CK, et al. Weight management using the internet a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]