Abstract

Background

Src family tyrosine kinases (SFKs) are often coincidently expressed but few studies have dissected their individual functions in the same cell during development. Using the classical embryonic lens as our model we investigated SFK signaling in the regulation of both differentiation initiation and morphogenesis, and the distinct functions of c-Src and Fyn in these processes.

Results

Blocking SFK activity with the highly specific inhibitor PP1 induced initiation of the lens differentiation program but blocked lens fiber cell elongation and organization into mini lens-like structures called lentoids. These dichotomous roles for SFK signaling were discovered to reflect distinct functions of c-Src and Fyn and their differentiation-state-specific recruitment to and action at N-cadherin junctions. c-Src was highly associated with the nascent N-cadherin junctions of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells. Its siRNA knockdown promoted N-cadherin junctional maturation, blocked proliferation, and induced lens cell differentiation. In contrast, Fyn was recruited to mature N-cadherin junctions of differentiating lens cells and siRNA knockdown suppressed differentiation-specific gene expression and blocked morphogenesis.

Conclusions

Through inhibition of N-cadherin junction maturation c-Src promotes lens epithelial cell proliferation and the maintenance of the lens epithelial cell undifferentiated state, while Fyn, signaling downstream of mature N-cadherin junctions, promotes lens fiber cell morphogenesis.

Keywords: Src family kinases, c-Src, Fyn, lens differentiation, morphogenesis

INTRODUCTION

The Src Family Kinases (SFKs), a family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases, are multifunctional signaling effectors that can be activated downstream of integrin (Cary et al., 1999; Shattil, 2005; Mitra and Schlaepfer, 2006), cadherin (Frame et al., 2002; McLachlan et al., 2007), and growth factor (Bromann et al., 2004; Veracini et al., 2005) receptors. As transducers of these signaling pathways SFKs control cell adhesion, cell communication and cytoskeletal organization (Thomas and Brugge, 1997; Frame et al., 2002; Frame, 2004), and are central to the regulation of cell proliferation, migration, survival and differentiation (Calautti et al., 1995; Brown and Cooper, 1996; Thomas and Brugge, 1997). While this functional diversity reflects the fact that there are many different Src family members, all of which share a common kinase domain, and each capable of regulating distinct aspects of cell behavior, few studies have dissected the roles of different SFKs within a single cell. Here, we examined the distinct, even antithetical, roles of Src kinases in regulating cell differentiation in studies with the embryonic lens, a classical model of development.

The earliest studies of Src kinases and lens development examined the effects of exogenous expression of the v-Src oncogene, a constitutively active form of the c-Src kinase. v-Src transformation of lens epithelial cells was found to maintain and promote a proliferative state, preventing differentiation and the formation of lentoid bodies, the multi-cellular, multilayered mini lens-like structures that form in lens culture (Menko and Boettiger, 1988). This outcome was associated with v-Src’s unregulated tyrosine phosphorylation of substrates in the cadherin complex, which negatively impacts a cell’s ability to assemble mature cadherin cell-cell junctions (Menko and Boettiger, 1988; Volberg et al., 1991; Hamaguchi et al., 1993; Frame et al., 2002). Indeed, this ability of v-Src to block differentiation is a universal phenomenon, shown for developmental systems as diverse as myoblasts, retinoblasts, keratinocytes, and chondrocytes (Muto et al., 1977; Yoshimura et al., 1981; Crisanti-Combes et al., 1982; Menko and Boettiger, 1988; Guermah et al., 1990; Falcone et al., 1991; Pierani et al., 1993; Falcone et al., 2003). In a reverse study with lens epithelial cells it was discovered that suppressing Src kinase activity induces maturation of N-cadherin junctions, expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p27 and p57, cell cycle withdrawal and lens differentiation initiation (Walker et al., 2002a). Similarly, deletion of the SFK c-Src in osteoblasts promotes their differentiation and the formation of bone (Marzia et al., 2000). Together these studies show that regulation of Src kinase activity is central to determining the timing of a cell’s proliferative, mass-producing phase and their decision to halt proliferation and embark on a differentiation pathway.

While Src kinases have long been associated with signaling the proliferative aspects of tissue development in studies such as those discussed above, knowledge of the function of SFKs in differentiation-state specific gene expression or tissue morphogenesis remains quite limited. Possibly the best evidence tying a Src kinase to cell differentiation exists for the SFK Fyn. In the brain, the absence of Fyn results in developmental defects linked to Fyn’s role in neurite outgrowth, myelin production, and oligodendrocyte survival (Grant et al., 1992; Osterhout et al., 1999; Wolf et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2004; Brackenbury et al., 2008; Goto et al., 2008; Relucio et al., 2009). Fyn also has been implicated in regulating keratinocyte differentiation (Calautti et al., 1998; Xie et al., 2005). As a downstream effector of both integrin and cadherin signaling pathways (Colognato et al., 2004; Liang et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2005) and an upstream activator of PI3K and Rac in signaling actin cytoskeletal reorganization (Samayawardhena et al., 2007), Fyn has the potential to be a crucial signal transducer of the morphogenetic aspects of development.

While the behavior of cadherin receptors in development is linked to Src kinase function, there is great complexity to the relationship between SFKs and cadherins. To a great degree this is a consequence of the function of Src kinases as both upstream regulators of cadherin junction maturation (Matsuyoshi et al., 1992; Hamaguchi et al., 1993; Takeda et al., 1995; Roura et al., 1999; Frame et al., 2002), and as downstream signaling effectors of mature cadherin junctions (Xie et al., 2005; McLachlan et al., 2007). In the embryonic lens both E-cadherin and N-cadherin are expressed in undifferentiated lens epithelial cells and each is essential for normal lens development (Xu et al., 2002; Pontoriero et al., 2009). However, of these two cadherins, only N-cadherin is expressed in differentiating lens fiber cells and is linked to a role in lens morphogenesis (Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000; Leonard et al., 2008; Leonard et al., 2011). The N-cadherin junctions of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells are principally organized as nascent junctions (Leonard et al., 2011), a dynamic but immature junctional type that forms at the tips of lamellipodial-like protrusions extended between opposing lateral cell membranes (Perez-Moreno et al., 2003). Maturation of these nascent N-cadherin junctions along the lateral interfaces of lens epithelial cells is temporally linked to lens differentiation initiation, and the resultant mature N-cadherin junctions serve as nucleation sites for assembly of the cortical actin filaments that are essential for lens fiber cell elongation (Weber and Menko, 2006a; Leonard et al., 2011). Formation of this cortical actin cytoskeleton also depends on PI3K (Weber and Menko, 2006b), a downstream signaling effector of the Src kinase Fyn. Therefore, the N-cadherin-Fyn-cytoskeleton axis emerges as a likely catalyst of the convergent extension-like process that drives lens epithelial cells to elongate and form differentiated lens fiber cells.

Our findings here add new understanding to the relationship between Src kinases and N-cadherin junctions in cell differentiation and tissue development. The SFK c-Src was discovered to prevent initiation of the lens differentiation program by maintaining N-cadherin complexes in the form of nascent junctions. The specific inhibition of c-Src function was necessary for N-cadherin junctions to mature and lens cells to transit to a differentiated phenotype. Our studies also revealed that the SFK Fyn was recruited to mature N-cadherin junctions and provided an essential signal for lens morphogenesis. Furthermore, SFK signaling was found to link N-cadherin junctions with the assembly of the higher ordered cytoskeletal structures required for morphogenesis of the lens.

RESULTS

Blocking SFK signaling induces lens epithelial cell differentiation

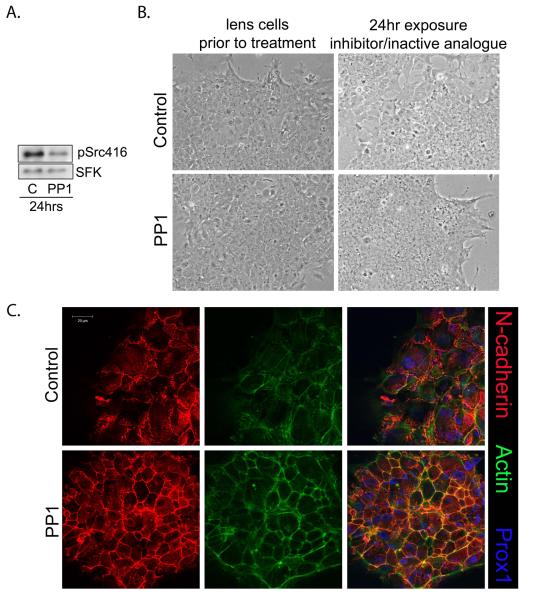

The regulation of epithelial cell differentiation by Src kinases was examined in a primary lens culture system that closely mimics lens differentiation as it occurs in vivo (Menko et al., 1984). The hallmarks of lens differentiation initiation that are recapitulated in this culture model include assembly of mature N-cadherin junctions leading to compaction of the lens epithelium (Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000), cell cycle withdrawal (Menko, 2002; Walker et al., 2002a), and induction of lens differentiation-specific proteins including the intermediate filament proteins filensin and CP49 (Blankenship et al., 2001), aquaporin-0 and αA-crystallin (Menko et al., 1987; Andley, 2007). These events are followed by dramatic morphological changes in which the lens epithelial cells elongate to form differentiated lens fibers cells that organize, as they differentiate, into lens tissue-like structures called lentoids (Menko et al., 1984). SFK signaling was effectively blocked in these primary lens epithelial cell cultures using the highly specific SFK inhibitor PP1, as shown by immunoblotting for phospho-Src-Y416 (Fig. 1A), a conserved, activated site shared by all SFKs (Thomas and Brugge, 1997; Schwartzberg, 1998). This inhibition of Src activity was achieved without affecting Src kinase expression. Phase-contrast imaging of lens epithelial cells following short-term exposure to PP1 (24 hrs from culture day 1, Fig. 1B) showed changes in organization of the epithelial monolayer, best evidenced by the inability to resolve cell borders, especially the loss of intercellular spaces between individual epithelial cells. Further analysis revealed that this 24 hr inhibition of Src kinase activity was sufficient to induce the lens epithelial cells to initiate their differentiation program. Among the more dramatic features of differentiation induction was the assembly of mature, N-cadherin junctions all along cell-cell interfaces (Fig. 1C, PP1) concurrent with the assembly of a cortical actin filament network that co-localized with these N-cadherin junctions (Fig. 1C, PP1). The mature N-cadherin junctions of PP1-exposed lens cultures were quite distinct from the N-cadherin nascent junctions of the control cultures (Fig. 1C, control). The undifferentiated lens epithelial cells in the controls primarily contained nascent N-cadherin junctions. Zipper-like and lacy in appearance, these nascent junctions were widely distributed over areas of overlapping lens cell membranes, and were associated with actin filaments in the form of stress-fibers.

Figure 1.

Blocking Src Kinase activity promotes maturation of N-cadherin junctions, formation of cortical actin filaments and compaction of the lens epithelium. Primary cultures of quail embryo lens epithelial cells were grown in the presence of the SFK inhibitor PP1 (A-C) for 24 hours beginning at culture day 1. Controls included PP3, an inactive analogue of PP1 (A, B), or the vehicle DMSO (C). (A) Western blot analysis with antibody to pSrc416 (active Src) showed that SFK activity was effectively inhibited following short-term (24hr) exposure of the lens cultures to PP1. (B) Phase contrast imaging showed that exposure to PP1 altered both morphology and organization of cells in the cultures, with individual cell-cell borders no longer discernable. (C) Immunostaining revealed that the morphological changes resulting from inhibition of SFK activity following exposure of lens epithelial cells to PP1 reflected the assembly of both mature N-cadherin junctions (red) and a cortical actin cytoskeleton (green). These studies also revealed that inhibiting SFK activity induced compaction of the lens epithelium, a principal morphogenetic marker of lens epithelial cell differentiation initiation. The cells also were immunolabeled for Prox1, a transcription factor expressed by lens epithelial cells upregulated with lens differentiation. Increased number of cells staining for Prox1 (blue), shown here in the overlay with N-cadherin (red) and F-actin (green) in the panels on the right, provided evidence that short-term (24 hr) inhibition of Src kinase activity promoted the initiation of lens cell differentiation. All studies shown were representative of a minimum of 3 independent studies. Phase contrast images were acquired at 10X; magnification bar=20μm.

Another feature of lens differentiation in vivo induced when Src kinase activity was inhibited in the lens cultures was compaction of the epithelial cell monolayer (Fig. 1C, compare PP1 to control). The degree of PP1-induced cell compaction was quantified by measuring individual cell areas in confocal images acquired from N-cadherin-labeled control and PP1-treated cultures. After only one day in the presence of the SFK inhibitor PP1 the area of the lens epithelial cells was significantly reduced to on average 176.10+/−9.61 μm2, as compared to an area of 342.17+/−20.59 μm2 in the control cultures. This result demonstrated that inhibition of SFK activity led to a greater than 45% reduction in cell area. Interestingly, differentiation-state specific lens epithelial cell compaction was previously linked to the assembly of mature N-cadherin junctions (Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000).

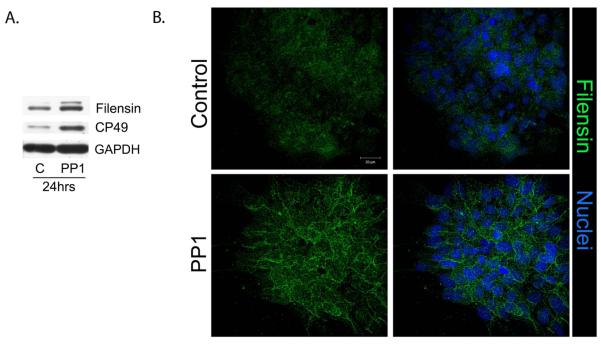

Increased nuclear localization of the transcription factor Prox1 is characteristic of lens cell differentiation (Wigle et al., 1999; Duncan et al., 2002; Cvekl and Duncan, 2007). Therefore, confocal microscopy imaging for Prox1 was performed in lens epithelial cell cultures following a 24 hr inhibition of SFK activity (Fig. 1C). The results showed that increased nuclear staining for Prox1 was concurrent with the assembly of mature N-cadherin junctions and the compaction of the lens epithelium. Biochemical evidence that inhibition of SFK activity promoted the differentiation program of lens epithelial cells was demonstrated by immunoblot analysis of the lens-specific intermediate filament proteins filensin and CP49. Expression of both of these cytoskeletal proteins was greatly increased in response to the 24hr inhibition of Src kinase activity (Fig. 2A). Confocal image analysis for filensin demonstrated that this intermediate filament protein had become concentrated along cell-cell borders (Fig. 2B, PP1), as occurs with lens differentiation in vivo (Blankenship et al., 2001). Control cells, cultured for the same time period in the presence of the vehicle DMSO, did not express high levels of filensin or organize this cytoskeletal protein at their cell interfaces (Fig. 2A,B, Control). The results presented here strongly support our conclusion that blocking SFK signaling in undifferentiated lens epithelial cells induced the lens differentiation program, and therefore, that a SFK activity was required to maintain the undifferentiated lens epithelial cell phenotype.

Figure 2.

Blocking Src Kinase activity promotes expression of lens differentiation-state specific intermediate filament proteins. Primary cultures of quail embryo lens cells were grown in the presence of the SFK inhibitor PP1 or the vehicle DMSO for 24 hours beginning at culture day 1. (A) Western blot analysis following short-term exposure of the lens cultures to PP1 showed that inhibiting SFK activity was sufficient to induce expression of the lens intermediate filament proteins filensin and CP49, both markers of initiation of the lens differentiation program. Control cultures were exposed to PP3; loading control was GAPDH. Immunofluorescence analysis (B) confirmed the increase in expression of filensin (green) when SFK activity was inhibited, and documented the differentiation-specific localization of filensin to cell borders. In the right panel in B, filensin localization was overlaid with staining for nuclei, which were labeled with TO-PRO3 (blue). Control cultures were treated with the vehicle DMSO. The results presented in this figure showed that short-term (24 hr) inhibition of Src kinase activity promoted the initiation of lens cell differentiation. All studies shown were representative of a minimum of 3 independent studies; magnification bar=20μm.

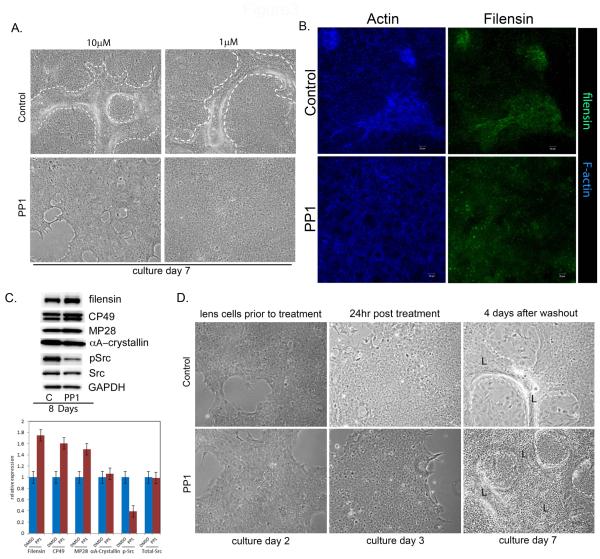

SFK signaling is required for lens morphogenesis

We next examined whether SFK signaling also was required at later stages of lens differentiation, specifically for the morphogenetic aspects of lens development. These studies were performed with primary lens cell cultures, and focused on the time period during which multi-cellular, multilayered lens-like lentoid structures are formed. Lentoids are shown here at culture day 7 by phase contrast imaging (Fig. 3A Control, lentoids outlined by white dashed lines) and by confocal imaging following staining for both the lens differentiation-specific intermediate filament protein filensin and for F-actin (Fig. 3B, Control). Labeling for F-actin delineated the organization of the lens fiber cells in the lentoid structures, and distinguished the lentoids from the surrounding cuboidal packed epithelium, while expression of filensin demonstrated the differentiated phenotype of the lentoid cells. When the lens cells were exposed to the SFK inhibitor PP1 throughout this 7-day culture period, lentoid formation was prevented, both at the standard concentration of PP1 inhibitor, 10μM, and at PP1 concentrations as low as 1μM (Fig. 3A, PP1).

Figure 3.

SFK activity is required for lens morphogenesis. (A) To examine the effect of inhibiting SFK activity on lens morphogenesis, the SFK inhibitor PP1 was added to primary cultures of quail embryo lens cells at culture day 1 and the cells grown in the presence of this inhibitor through culture day 7. During this time period extensive lentoid bodies (outlined with a white dashed line) formed in the control, PP3, treated cultures. Inhibition of SFK activity with PP1 throughout this time period blocked lentoid formation (lens morphogenesis), both at the standard concentration of 10 μM PP1 and at a concentration of PP1 as low as 1 μM. (B) To examine the temporal requirement of SFK activity in lens morphogenesis SFK activity was not inhibited until culture day 4, just prior to the time when lentoids begin to form. These cultures were exposed to the SFK inhibitor PP1 inhibitor from culture day 4 through culture day 7. In this scenario lens morphogenesis (lentoid formation) still was effectively blocked, as seen in confocal images of cultures labeled for filensin (green) and F-actin (blue), magnification bar=20μm. Control cultures exposed to the vehicle DMSO formed normal lentoid structures. This result revealed that the SFK activity signaling lens morphogenesis was required for lentoid formation only during the time period of lentoid formation, and not during the differentiation stages that preceded morphogenesis. (C) Immunoblot analysis of cultures exposed to PP1 from culture day 1 through culture day 8, compared to control cultures (C) exposed to the vehicle DMSO. Results showed that inhibition of SFK activity resulted in increased expression of the lens differentiation-specific proteins filensin, CP49, and MP28 (aquaporin-0) even though morphogenesis was blocked. Immunoblotting for active SFKs (pSrc) showed that SFK activity was effectively blocked by PP1 without impacting SFK expression (Src). Loading control was GAPDH. Immunoblot results from three independent experiments were quantified and presented as a bar graph. (D) A reversal experiment was performed in which primary lens cultures were exposed to PP1 or PP3 for one day, the inhibitor/inactive analogue removed, and the cells cultured for an additional 4 days. The results showed that on removal of the inhibitor, cultures that had been exposed to PP1 retained their competence to undergo morphogenesis. All studies shown were representative of a minimum of 3 independent studies. Phase contrast images were acquired at 10X.

Immunostaining of cultures exposed to PP1 during the time that lentoid structures form in control cultures (culture day 4-7) demonstrated that filensin continued to be expressed in the absence of SFK signaling even though lentoid formation was blocked (Figure 3B, PP1). Biochemical analysis supported this finding. Western blotting was performed on primary lens cells grown in the presence of the SFK inhibitor PP1 from day 1 through day 8 in culture. These conditions prevented lentoid formation, but lens differentiation-specific proteins continued to be expressed, including the intermediate filaments proteins CP49 and filensin, αA-crystallin, and aquaporin-0 (Figure 3C). These results revealed, for the first time, a requisite and specific role for a Src family kinase in signaling lens morphogenetic differentiation.

We examined whether lens cells could recover their ability to undergo morphogenetic differentiation after exposure to the SFK inhibitor PP1. For this study undifferentiated lens epithelial cells were exposed to PP1 for 24 hrs, the inhibitor removed and replaced with normal growth media and the cells cultured for an additional 4 days. These cultures formed lentoid structures similar to the control cultures (Figure 3D), indicating that SFK reactivation was sufficient to rescue the ability of the lens cells to undergo morphogenesis.

A time-course analysis was performed to distinguish between the role of SFKs in lens morphogenesis and the function of SFKs in undifferentiated lens epithelial cells, as well as to pinpoint the stage of differentiation at which SFK signaling was required for lens morphogenesis. In this study, primary lens epithelial cells were exposed to the Src inhibitor PP1, or its vehicle DMSO, starting at culture days 1, 2, 3, or 4, and the cells grown in the presence of the inhibitor (or DMSO) through culture day 7, during which time lentoid structures formed in the controls (Fig. 3B). The addition of the SFK inhibitor at culture day 4 was a most important time point, being just one day before lens morphogenesis commences. The results showed that lentoid formation was blocked regardless of the time point from which inhibition of SFK activity was begun, including addition of PP1 at culture day 4. As shown for this time point, staining for F-actin revealed that the cells remained as a monolayer and failed to organize lentoid structures (Fig. 3B, PP1), maintaining a pattern of organization typical of cells in the equatorial epithelium (Leonard et al., 2011). These studies strongly support the conclusion that SFK activity is required for lens morphogenesis.

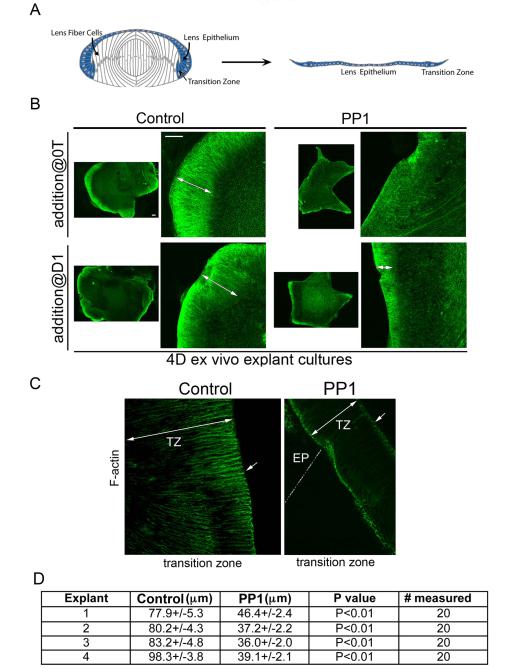

SFK signaling is required for lens fiber cell elongation

An integral part of lens morphogenesis is the dramatic elongation of the differentiating lens fiber cells. To examine the requirement for SFK signaling in this process we used a chicken embryo lens epithelial explant culture system we previously developed for studying determinants of lens fiber cell elongation (Leonard et al., 2011). These ex vivo explants contain the entire lens epithelium with the transition zone, the region of the lens where fiber cell elongation commences, located at the edges of the explants, their apical/basal axis oriented parallel to the culture dish (modeled in Fig. 4A). This orientation of cells in the transition zone results from their position in the embryonic lens, somewhat perpendicular to the lens epithelium, as they turn the corner of the posterior lens from where they are added concentrically to the cortical fiber zone as they differentiate. Labeling of F-actin with fluorescent-phalloidin defines the borders of lens fiber cells (Weber and Menko, 2006a), revealing lens fiber cell morphology and, thereby, the state of elongation of cells in the transition zone (Fig. 4B,C, controls, the length of cells in the transition zone noted by double-headed white arrows). In these ex vivo explants, as occurs in the lens in vivo, the cells of the transition zone elongated as they differentiated to form new fiber cells.

Figure 4.

Src kinase signaling is required for lens fiber cell elongation. Chick embryo lens ex vivo explant cultures were prepared from E10 lenses as diagrammed in A. The transition zone in which lens fiber elongation begins is located along the edges of the explants, just adjacent to the lens epithelium. (B) Explants were exposed to the SFK inhibitor PP1 or the vehicle control DMSO beginning at either the time of culture preparation (0T) or culture day 1 (D1), grown though culture day 4 (4D), stained with fluorescent-tagged phalloidin to label F-actin, and imaged with confocal microscopy; magnification bar=100μm. Double-headed white arrows denote elongation of cells in the transition zone. Blocking SFK activity effectively suppressed fiber cell elongation when added at D1, but elongation was completely prevented only when SFK activity was blocked from time 0 (0T). Inhibition of fiber cell elongation in the absence of SFK signaling was quantified in explants grown in culture for five days after the addition of the SFK inhibitor PP1, or its vehicle DMSO, at culture day 1. For this study F-actin was labeled with fluorescent-phalloidin to highlight cell-cell borders of the elongating fiber cells, and Z-stacks collected by confocal imaging through the transition zone (TZ) by confocal microscopy (the image in C if of a single optical plane). Double-headed white arrows denote the length of the TZ, white single arrows the apical tips of elongating fiber cells. In the PP1-treated explant the dotted white line denotes the position of the epithelium (EP), most of which is not visualized in this optical plane. The length of elongating fiber cells was measured by tracing them, following the cells through different optical planes as necessary, using LSM510 software. (D) The study evaluated the length of fiber cells in explants from 4 different studies, labeled here as explants 1-4. The lengths of 20 fiber cells were measured in each explant (# measured), for both control (DMSO) and PP1-treated explants. Lengths are provided as μm, with standard error of the mean, and p values. The average length of fiber cells was 85μm in the control explants, and was reduced to only 40μm when SFK activity was inhibited beginning at culture day one. F-actin labeling showed that the inhibition of fiber cell elongation in the absence of SFK signaling reflected suppression of cortical actin filament assembly along the lateral cell interfaces of lens fiber cells in the transition zone (C). The results presented were representative of 4 independent explant studies.

To examine the temporal requirement for SFK function in fiber cell elongation SFK activity was blocked in lens explants at different times during a 4-day culture period. For this study explants were exposed to the SFK inhibitor PP1 beginning at the time of explant preparation (time 0), culture day 1, culture day 2, and culture day 3. Explants were stained with fluorescent-phalloidin and evaluated for the effects of inhibiting Src kinase activity on fiber cell elongation by confocal imaging. There was extensive fiber cell elongation in the transition zone of the control explants (Fig. 4B, control, double-headed white arrows). Blocking SFK signaling at any time during this culture period interfered with fiber cell elongation, shown here for two of the time points of PP1 addition, time 0 (T0) and culture day 1 (Fig. 4B, PP1). It was only when SFK signaling was inhibited through the entire culture period, beginning at T0, that lens fiber cell elongation was completely prevented (Fig. 4B).

To quantify the effect of blocking SFK activity on lens fiber cell elongation, explants were cultured in the presence or absence of the SFK inhibitor PP1 for 5 days following the addition of PP1 at culture day 1 and the explants labeled for F-actin to define cell borders. Explants were imaged by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4C; the PP1-treated explant also shown in a higher intensity image in Supplemental Figure 1) and Z-stacks collected through the transition zone of each explant, from which the average lengths of fiber cells were traced and measured using Zeiss LSM510 software. The average length of fiber cells was 85 μm in control explants, compared to only 40 μm when SFK activity was blocked beginning at culture day 1 (Fig. 4D). This result demonstrated for the first time that SFK signaling was required for lens fiber cell elongation.

Actin staining in this study provided additional insight into the pathway by which Src kinases regulate lens fiber cell elongation. In previous studies from our laboratory we show that mature N-cadherin junctions are a principal site for assembly of cortical F-actin filaments in differentiating lens cells, and that both N-cadherin and F-actin are required for fiber cell elongation (Leonard et al., 2011). Comparing F-actin labeling of transition zone cells in control explant cultures to those grown in the presence of the SFK inhibitor PP1 (Figure 4C) revealed that blocking Src kinase activity suppressed assembly of cortical actin filaments along the lateral interfaces of transition zone cells. This result suggested that the mechanism by which SFKs regulate lens fiber cell elongation involved a role in the induction of actin filament assembly. We believe that the studies presented here provide the first functional link between SFK signaling and the mechanisms that regulate cell elongation during tissue morphogenesis.

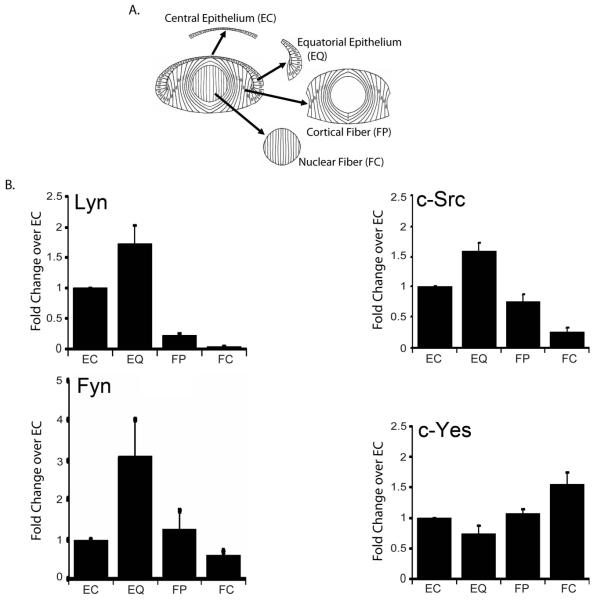

Unique, differentiation-state specific patterns of expression of Src kinases in the developing lens

The studies above showed that Src kinase activities were required at two different stages of lens differentiation, both in undifferentiated lens epithelial cells where they prevented differentiation initiation, and for lens fiber cell elongation and morphogenesis, suggesting that these phenomena were dependent on distinct Src kinase family proteins. The four most commonly expressed SFK members, c-Src, c-Yes, Fyn and Lyn are all expressed in the adult lens (Bozulic et al., 2004; Tamiya and Delamere, 2005). To begin to understand whether there may be distinct roles for individual SFKs during different aspects of lens development we determined the temporal expression of these SFK family members in relation to the lens cell differentiation state in vivo. For these studies E10 chicken lenses were microdissected into four differentiation-state specific zones (modeled in Fig. 5A): 1) the central epithelium (EC), which is comprised of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells; 2) the equatorial epithelium (EQ), located around the lens equator where lens cells transit from a state of active proliferation to cells that have withdrawn from the cell cycle and initiated their differentiation; 3) the cortical fiber cells (FP), a zone of both cell and tissue morphogenesis where the lens cells acquire their classic, highly elongated fiber cell morphology as they arrange themselves into a hexagonally packed tissue structure; and 4) the central fiber zone (FC), a region of terminal lens fiber cell differentiation (Menko, 2002).

Figure 5.

Distinct expression patterns for SFK members Lyn, c-Src, Fyn and c-Yes during lens cell differentiation. E10 chick embryo lenses were microdissected into four distinct regions of differentiation, modeled in A, which included the undifferentiated cells of the central lens epithelium (EC), the equatorial epithelium where lens differentiation initiation is initiated (EQ), cortical fiber cells, the region of lens fiber cell elongation/morphogenesis (FP), and the nuclear fiber cells where lens fiber cells mature (FC). (B) Equal protein fractions from each region of differentiation were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for the four most commonly expressed SFKs: Lyn, c-Src, Fyn and c-Yes. For each SFK, the immunoblots were scanned and quantified using Kodak 1D analysis software. The results are presented in B in graphical form, representing the average of at least three independent studies. The SFK Lyn was most highly expressed in lens epithelial cells, c-Src in both lens epithelial and cortical fiber cells, Fyn in the lens equatorial and cortical fiber zones, and c-Yes in terminally differentiating fiber cells.

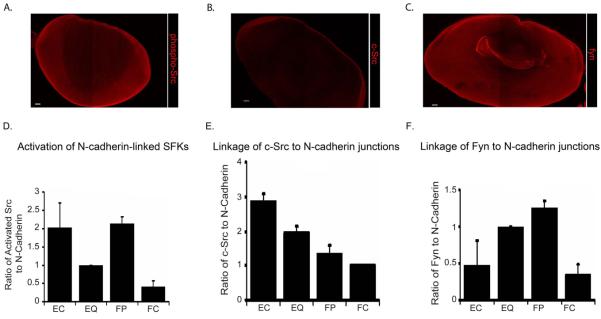

The microdissected lens fractions were immunoblotted for c-Src, c-Yes, Fyn and Lyn (Fig. 5B). Each SFK analyzed showed unique differentiation-state specific patterns of expression in the developing lens. Lyn was limited to lens epithelial cells, and present in both EC and EQ zones. c-Src was most highly expressed by lens epithelial cells, and expression then dropped with lens cell differentiation state. Fyn was most highly expressed in the EQ zone, and remained high in the FP zone of fiber cell morphogenesis. c-Yes, expressed throughout lens differentiation, was the only SFK analyzed whose levels were highest in the terminally differentiating cells of the FC zone. The unique expression patterns of these different Src kinases were consistent with each having separate and distinct functions in lens differentiation. Immunolocalization of c-Src and Fyn (Fig. 6B,C) confirmed the biochemical analysis, showing c-Src most highly expressed in lens epithelial cells, and that Fyn expressed both by lens epithelial cells and across the FP zone, the region of fiber cell elongation. Immunolocalization for phosphoSrc, the activated form of the SFKs, showed that Src kinase activity was high in both lens epithelial and differentiating lens fiber cells (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Differentiation-state specific N-cadherin-linked SFK signaling. Localization of c-Src, Fyn and active (phosphorylated) SFKs (phosphoSrc) in day 10 chicken embryo lenses was determined by immunofluorescence analysis of lens sections, images acquired by confocal microscopy (A-C). (B) c-Src was most highly localized to cells of the lens epithelium, (C) Fyn was highly localized in the lens epithelium and in differentiating cortical fiber cells, and (A) SFKs were highly activated in both of these zones of lens differentiation. Magnification bar=50μm. (D-F) Co-immunoprecipitation analysis was performed on differentiation-state specific fractions of E10 chick embryo lenses isolated by microdissection into four distinct regions of differentiation as modeled in Figure 5, EC, EQ, FP and FC. In independent studies, these lens fractions were immunoprecipitated for N-cadherin, and the immunoprecipitated N-cadherin complexes immunoblotted with antibodies to N-cadherin and (A) pSrc416, the activated form of the Src kinases, (B) c-Src or (C) Fyn. The immunoblots were scanned and quantified using Kodak 1D software. The results were plotted in D-E as a ratio of the level of co-precipitated activated (phospho)Src, c-Src or Fyn to the level of N-cadherin immunoprecipitated in that fraction, each graph representing an average of at least three independent studies.

Biphasic, differentiation-state specific activation of N-cadherin-linked SFKs during lens development

Src kinases have been identified both as negative regulators of cadherin junction stability (Menko and Boettiger, 1988; Volberg et al., 1991) and as downstream effectors in signaling pathways activated by cadherin junctions (McLachlan et al., 2007). Using a co-immunoprecipitation approach we investigated whether the distinct roles for SFKs in lens differentiation might reflect SFK function at cadherin junctional complexes. N-cadherin was chosen for this study because of its known regulatory role in lens differentiation. Extracts from each of four differentiation-specific zones of the embryonic lens isolated by microdissection (modeled in Fig. 5A) were immunoprecipitated with antibody to N-cadherin, and immunoblotted with antibody to activated SFKs (phospho-Src-Y416) as well as to N-cadherin. The activation of N-cadherin-linked SFKs was quantified (ratio of activated Src/N-cadherin) following densitometric analysis of the immunoblots (Fig. 6D). This analysis revealed that active Src kinases were temporally linked to N-cadherin junctional complexes with a biphasic, differentiation-state specificity in cells of the undifferentiated lens epithelium (EC), and during the period of lens fiber cell elongation/morphogenesis (FP) (Figure 6D). This result is consistent with our findings that Src kinase family members maintain lens epithelial cells in their undifferentiated state (EC) and signal lens fiber cell morphogenesis (FP), and extends those findings by showing that the roles of SFKs in these regions of lens differentiation was linked to their signaling function at N-cadherin junctions.

Differentiation-state specificity of Src and Fyn association with N-cadherin

To identify the active Src kinases associated with N-cadherin junctions in the embryonic lens we performed co-immunoprecipitation analysis (IP: N-cadherin, blot: antibody to each of the four commonly expressed SFKs: Src, Fyn, Yes and Lyn) with each of the differentiation-specific fractions of the lens (EC, EQ, FP, FC). c-Src and Fyn, but not c-Yes or Lyn, were linked to N-cadherin junctional complexes (Fig. 6E,F). Their association with N-cadherin was differentiation-state specific and greatest in regions with high N-cadherin-linked Src kinase activity. The SFK c-Src was most highly linked to the N-cadherin complexes of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells (Fig. 6E, EC), and the SFK Fyn to N-cadherin junctions in regions of fiber cell elongation/morphogenesis (Fig. 6F, FP). These results strongly implicate c-Src as the active SFK of N-cadherin junctions in the EC zone, and Fyn as the active Src kinase of N-cadherin junctions in the FP zone.

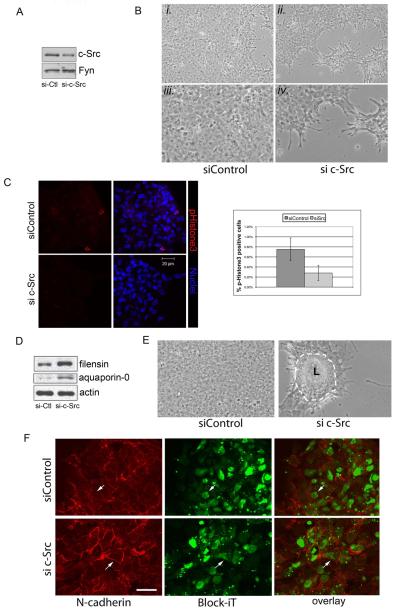

Knockdown of c-Src promotes differentiation initiation by inducing maturation of N-cadherin junctions

The high homology of SFK members, their ability to compensate for one another in knockout mice (Stein et al., 1994; Lowell and Soriano, 1996) and the fact that inhibitors of SFK activity target all SFKs that are expressed in a cell has made it difficult to determine the precise role of individual SFKs in differentiation. However, successful identification of SFK member-specific functions has been possible to achieve through targeted siRNA knockdown (Colognato et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2008). Using a siRNA approach we specifically knocked down c-Src in lens epithelial cell cultures to assess the role of this SFK in lens cell differentiation. c-Src expression was effectively suppressed without effecting expression of another SFK family member (Fig. 7A, Fyn). Knockdown of c-Src led to a decreased number of cells (Fig. 7B, phase imaging at 48hrs post-transfection) and a decrease in cells positive for the mitosis marker phosphoHistone3 (Fig. 7C). These results provided strong evidence that knockdown of c-Src in lens epithelial cells inhibited lens cell proliferation and promoted cell cycle withdrawal. In addition, in the absence of c-Src signaling lens cell differentiation initiation was induced, as evidenced by the increased expression of lens differentiation-specific proteins filensin and aquaporin-0 (MP28) (Figure 7D). This phenotype was identical to that obtained by blocking SFK signaling in lens cells with PP1, an inhibitor that blocks activity of all Src kinases (see Fig. 1). However, in contrast to the PP1 results, the specific knockdown of c-Src did not interfere with the formation of lentoid structures. In fact, morphogenesis of differentiated lens structures was promoted following c-Src siRNA knockdown, evidenced by the early appearance of lentoid structures (Fig. 7E, 72 hours following siSrc knockdown). These results demonstrated that the SFK member c-Src has an important role in the behavior of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells, its knockdown leading to differentiation initiation, and that c-Src function was not required for lens morphogenesis.

Figure 7.

siRNA c-Src knockdown promoted N-cadherin junction maturation and lens cell differentiation/morphogenesis. A siRNA approach was used to knockdown c-Src expression (si c-Src) in primary quail embryo lens cell cultures. Control cultures were transfected with siCONTROL non-targeting siRNAs (labeled as siControl or si-Ctl). (A) Immunoblot analysis showed that c-Src was effectively knocked-down without blocking the expression of the SFK Fyn. (B) Phase contrast imaging at 48 hrs post-transfection showed that knockdown of c-Src blocked expansion of lens epithelial cells; iii and iv are higher magnification images of representative areas from i and ii, respectively. (C) Immunostaining for phosphoHistone3, a mitotic cell marker confirmed that the block in population expansion following c-Src siRNA knockdown resulted, at least in part, from the inhibition of lens cell proliferation (pHistone3, red; nuclei, blue); results quantified in the panel to the right. (D) Immunoblotting for filensin and aquaporin-0, with β-actin as control, showed that c-Src siRNA knockdown promoted lens differentiation-specific gene expression. (E) Phase contrast imaging at 72 hrs post-transfection showed that siRNA knockdown of c-Src promoted formation of lentoids (L, outlined with a dashed white line). (D) To examine if the c-Src siRNA knockdown affected maturation of N-cadherin junctions, primary quail embryo lens cultures were transfected with either c-Src siRNA or siCONTROL non-targeting siRNAs, and each co-transfected with the BLOCK-iT fluorescent oligo (green) to mark transfected cells. Confocal imaging following immunostaining for N-cadherin (red) showed that c-Src knockdown induced maturation of N-cadherin junctions, seen as linear staining for N-cadherin along cell-cell interfaces of BLOCK-iT-positive (green) cells. White arrows point to the same BLOCK-iT-positive cell in each set of images. All studies were representative of at least three independent experiments. Phase contrast images were acquired at 10X; magnification bar=20μm.

We have shown in this study that c-Src was highly linked to the N-cadherin junctions of lens epithelial cells and that the activity of N-cadherin-linked SFKs was high in cells of the undifferentiated lens epithelium. Here, we investigated whether the mechanism of action of c-Src in lens epithelial cells involved a role in regulating the state of assembly of N-cadherin junctions, whose maturation we previously show is required for lens differentiation initiation (Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000). For these studies lens epithelial cell cultures were co-transfected with c-Src siRNA and Block-iT, a fluorescein-labeled double-stranded RNA oligomer that tags the transfected cells. The state of organization of N-cadherin junctions in c-Src siRNA transfected (Block-iT-positive) cells was determined by confocal microscopy imaging, and compared to cultures co-transfected with control siRNA and Block-iT (Fig. 7F). The knock-down of c-Src induced formation of mature N-cadherin junctions, which appear as linear staining for N-cadherin all along the cell-cell borders of Block-iT positive cells. This assembly of mature N-cadherin junctions was in direct contrast to the zipper-like state of organization typical of nascent N-cadherin junctions, which was characteristic of the non-transfected cells in these cultures, and of most cells in the control cultures. The induction of N-cadherin junctional maturation when c-Src expression was knocked-down showed that c-Src played a principal role in maintaining N-cadherin cell-cell contacts in undifferentiated lens epithelial cells as nascent junctions. This finding also linked nascent N-cadherin junctions to an active role in sustaining the undifferentiated state of lens epithelial cells.

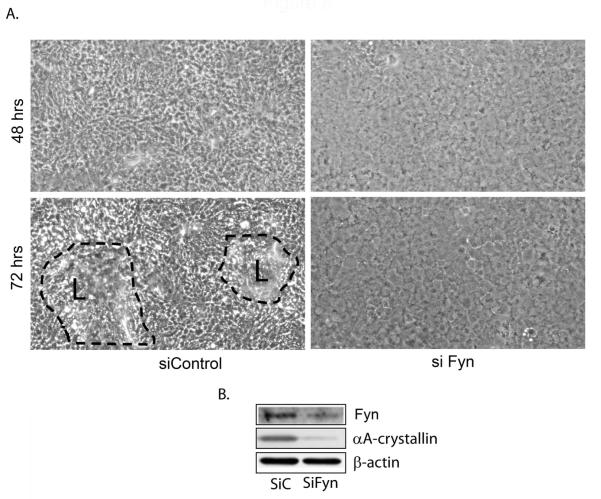

Fyn is necessary for lens morphogenetic differentiation

Long-term inhibition of all SFK activity with the inhibitor PP1 promoted lens cell differentiation initiation but blocked lens morphogenesis (Fig. 3A). Since lens epithelial cells in which expression of c-Src was blocked were able to complete both biochemical and morphogenetic differentiation, a SFK member other than c-Src must provide the SFK signal required for the morphogenetic differentiation of lens fiber cells. Here we investigated whether the SFK Fyn signaled lens morphogenesis. Fyn was chosen for this study because it was highly expressed by differentiating lens cells in vivo (Fig. 5) and was highly associated with N-cadherin junctions during the period of fiber cell morphogenesis (Fig. 6). For these studies Fyn expression was knocked down in primary lens epithelial cell cultures using a siRNA approach (Fig. 8B). The lens epithelial cells in the Fyn knockdown cultures failed to form lentoid structures (Fig. 8A, 72 hrs), the hallmark of lens morphogenetic differentiation. The knockdown of Fyn also blocked the increased expression of αA-crystallin that normally accompanies lens cell differentiation (Figure 8B). The block of lens morphogenesis in Fyn knockdown lens cell cultures paralleled the effect of blocking SFK activity with the inhibitor PP1 during the time period that lentoids form, providing strong evidence that Fyn was the SFK activity required for signaling lens fiber cell morphogenesis.

Figure 8.

siRNA Fyn knockdown blocked lens morphogenesis. A siRNA approach was used to knockdown the expression of the SFK Fyn (si Fyn) in primary quail embryo lens cell cultures. Control cultures were transfected with siCONTROL non-targeting siRNAs (labeled as siControl or siC). Representative phase contrast images were shown at both 48 and 72 hrs post-transfection (A). Knockdown of Fyn inhibited formation of lentoids (L, outlined with dashed black lines), which had begun to form in the control cultures at 72 hrs post-transfection. Immunoblot analysis (B) showed both the efficacy of Fyn siRNA knockdown (Fyn) and that the expression of the lens differentiation-specific protein αA-crystallin was suppressed in the Fyn siRNA knockdown cultures; β-actin was included as a loading control. These studies were representative of at least three independent experiments. Phase contrast images were acquired at 10X.

DISCUSSION

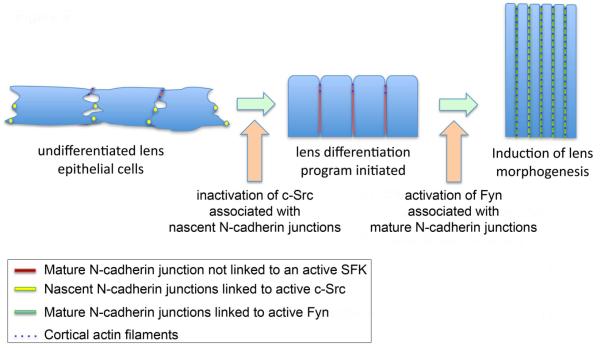

While it is generally acknowledged that SFK function is involved in cell differentiation processes, there has been limited understanding of either the particular SFK members responsible for signaling differentiation events or the mechanism by which these SFKs regulate cell differentiation and morphogenesis. Now, in studies focused on the embryonic lens, a classical model of developmental, and ex vivo models that closely replicate the lens differentiation and morphogenesis processes, we identified separate roles for different SFK members within a single cell type, and linked their function to distinct regulatory events in development. These discoveries revealed a principal role for c-Src in maintaining the undifferentiated state of lens epithelial cells, and a requisite function for the Src tyrosine kinase Fyn in signaling lens morphogenetic differentiation (model, Fig. 9). These distinct functions of Src and Fyn in lens differentiation involved their respective actions as upstream regulator and downstream effector of N-cadherin junctions.

Figure 9.

Role of N-cadherin-linked Src kinases in lens differentiation and morphogenesis. The N-cadherin junctions along cell-cell borders of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells are organized principally as nascent junctions. This immature form of cadherin junction is present in adhesive puncta at discontinuous regions of cell-cell contact between neighboring epithelial cells. In the undifferentiated cells of the lens these junctions are linked to active c-Src kinase. Inactivation of this Src kinase promotes maturation of the N-cadherin junctions, zipping up the cell-cell interfaces, and resulting in compaction of the lens epithelium. The SFK Fyn is recruited to these mature N-cadherin junctions where it signals lens fiber cell morphogenesis, a process that involves the role of Fyn in organization of the actin cytoskeleton along the cell-cell borders of differentiating lens fiber cells.

Our finding that SFK function was integrated with that of N-cadherin in the developing lens is particularly significant because these junctions are recognized as crucial regulators of lens cell differentiation and morphogenesis (Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000; Pontoriero et al., 2009; Leonard et al., 2011). We now show that the nascent cadherin junctions that predominate along the lateral cell-cell borders of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells (Leonard et al., 2011) are maintained as such by the SFK c-Src. Maturation of these junctions following the inactivation of c-Src is responsible for zipping up the cells’ lateral interfaces and compaction of the lens epithelium, a process central to lens development, and a prerequisite to fiber cell elongation. Therefore, the mechanism by which c-Src promotes and maintains the lens epithelial cell undifferentiated state is linked to its role in preventing N-cadherin junction maturation. v-Src, a constitutively active form of c-Src, also blocks maturation of cadherin junctions (Menko and Boettiger, 1988; Volberg et al., 1991; Matsuyoshi et al., 1992; Hamaguchi et al., 1993; Takeda et al., 1995; Roura et al., 1999; Avizienyte et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2002a; Frame, 2004).

There are many targets for c-Src in the cadherin complex. These include the cadherin receptor itself, β-catenin, γ-catenin, and p120-catenin (Volberg et al., 1991; Matsuyoshi et al., 1992; Hamaguchi et al., 1993; Calautti et al., 1998; Ozawa and Ohkubo, 2001; Lilien and Balsamo, 2005). Implicit to our discovery that c-Src regulates the timing of lens cell differentiation initiation by preventing N-cadherin junction maturation is that conditions permissive for differentiation to commence would require both inactivation of c-Src and dephosphorylation of c-Src’s protein targets in the N-cadherin complex. Such a mechanism is likely to involve molecules such as the c-Src Kinase, CSK, that targets the negative regulatory domain of c-Src (Thomas and Brugge, 1997; Pedraza et al., 2004), and dephosphorylation of proteins in the cadherin complex by tyrosine phosphatases including SHP2 and PTP1B (Balsamo et al., 1998; Schnekenburger et al., 1999; Ukropec et al., 2000; Wadham et al., 2003). In the developing lens, it is already known that maturation of N-cadherin junctions involves decreased tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin, which is temporally linked to recruitment of SHP2 to N-cadherin complexes (Leonard et al., 2011). In addition, the SFK regulator CSK is highly expressed in equatorial epithelial cells, the region of the developing lens where N-cadherin-linked-c-Src activity is suppressed, allowing N-cadherin junctions to mature.

Mature N-cadherin junctions have an intrinsic role in differentiation-state specific morphogenesis, both in the elongation of lens fiber cells (Leonard et al., 2011) and in the morphogenetic processes needed to organize fiber cells into lens-like lentoid structures (Ferreira-Cornwell et al., 2000). The function of N-cadherin junctions in fiber cell elongation stems, in part, from their role as nucleation sites for the polymerization of cortical actin (Leonard et al., 2011), a cytoskeletal element important to force generation for cell movement and in determining cell shape. Signaling by PI3K and its downstream effector Rac are also required for the organization of cortical actin structures in the lens and for lens morphogenesis (Weber and Menko, 2006a). Both N-cadherin and Fyn are upstream activators of PI3K and Rac (Nakagawa et al., 2001; Noren et al., 2001; Braga, 2002; Goodwin et al., 2003; Xie et al., 2005; Samayawardhena et al., 2007) and Fyn is activated in response to conditions that induce formation of mature cadherin junctions (Xie et al., 2005). Our studies now show that SFK activity is required for both assembly of the cortical actin cytoskeleton of lens fiber cells and for elongation of these cells, and reveal a direct role for Fyn in signaling the formation of differentiated lentoid structures. These findings implicate Fyn as a principal regulator of the pathway that signals lens fiber cell morphogenetic differentiation through its regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. We propose that the activation of Fyn at mature N-cadherin junctions in the developing lens in turn activates the PI3K/Rac signaling axis, inducing assembly of cortical actin filaments that direct elongation of differentiating lens fiber cells. By demonstrating here that the SFK Fyn was an essential molecular component of the signaling pathway required for morphogenetic differentiation in the lens our studies have added a new layer of understanding to the role of Src family kinases in signaling pathways that regulate tissue morphogenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEEDURES

Preparation and Treatment of Primary Lens Cultures

Differentiating primary lens cell cultures were prepared as described previously (Menko et al., 1984). Briefly, lens cells were isolated from embryonic day 9 (E9) quail (B&E Eggs, York Springs, PA) lenses by trypsinization and agitation. Quail embryos lens cells were chosen for these studies because they exhibited greater growth potential in culture than chicken embryo lens cells, the original source for these cultures, while still maintaining the same differentiation characteristics. Chicken embryos were the source for embryonic lenses used in all other studies presented here. Quail embryo lens cells isolated for primary culture were plated on a laminin substrate in 35mm dishes and cultured in Media 199 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA). To inhibit Src kinase activity in these lens cell cultures the Src kinase inhibitor PP1 (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY) was added to the media at 10μM unless otherwise indicated. In lens cell cultures PP1 has been shown to be a highly specific and potent inhibitor of SFK activation (Walker et al., 2002a; Walker et al., 2002b; Zhou and Menko, 2004), which does not affect potential off-targets such as the MAP kinase p38 (Zhou and Menko, 2004). PP3, the inactive analogue of PP1, was used initially as a control for PP1, and was later replaced with the vehicle DMSO after PP3 was proven to have no effect on growth or differentiation of lens cultures.

Ex vivo explant cultures

Epithelial explants were prepared from E10 chicken lenses (B&E Eggs, York Springs, PA). The lens fiber cell mass was removed from the lens proper through the posterior aspects of the lens, leaving behind the entire lens epithelium attached to its endogenous basement membrane, the lens capsule, as previously described (Leonard et al., 2011). The explants were pinned to a culture dish, cell side up, as modeled in Fig. 4A. The undifferentiated epithelial cells that line the anterior surface of the lens are located in the center of the ex vivo explants, surrounded by the epithelial cells of the equatorial zone, the region of differentiation initiation. The lens transition zone where lens fiber cell elongation begins is located at the outermost edges of the explant. The explants were cultured in Media199 with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA). For inhibition of SFK activity in the ex vivo explant cultures PP1 was added to the culture media at 10μM. The vehicle for PP1, DMSO, was used as control.

siRNA Knockdown of c-Src and Fyn

c-Src and Fyn were each silenced in primary lens epithelial cell cultures using a pool of four siRNA duplexes designed as a custom SMARTpool plus by Dharmacon Research, Inc. (Lafayette, Colorado). To enhance specificity, this pool of siRNA duplexes included an ON-TARGET modification, which eliminated non-specific effects of the sense strand by blocking sense strand off targets with RISC-RNA-induced silencing complexes. As a negative control the lens cell cultures were transfected with siCONTROL Non-targeting siRNAs (Dharmacon, Lafayette, Colorado). For maximum knockdown of the target molecules cultures were transfected at 24 and 48 hours after plating using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) and 50-100nM of pool siRNA or non-targeting siRNA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. As an indicator of transfected cells in the immunolocalization studies lens cultures were co-transfected with BLOCK-iT fluorescent oligo (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA).

Lens Microdissection

Lenses were isolated from E10 chicken embryos (B&E Eggs, York Springs, PA) and microdissected as previously described (Walker and Menko, 1999) to yield four distinct regions of differentiation; central anterior epithelium (EC), equatorial epithelium (EQ), cortical fiber cells (FP), and central fiber zone (FC), as modeled in Fig. 5A.

Protein Extraction, Co-Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Microdissected lens fractions and cultures were extracted in Triton/OG buffer (44.4M n-Octyl b-D glucopyranoside, 1% Triton X-100, 100mM NaCl, 1mM MgCl2, 5mM EDTA, 10mM imidazole, pH 7.4) containing 1mM sodium vanadate, 0.2mM H202, and Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Protein concentrations were quantified using the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). For direct immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates, 15μg of protein extracts were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE) on precast 4-12% Tris-Glycine gels (Novex, San Diego, CA). For immunoprecipitation studies 100 lenses were microdissected into the four differentiation specific fractions, the fractions extracted as above, and then each cell fraction subjected in its entirety to immunoprecipitation. This approach allowed for similar amounts of N-cadherin to be pulled down from each fraction by immunoprecipitation. Briefly, samples were incubated at 40 C sequentially with primary antibody and then protein G (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and the immunoprecipitates subjected to SDS/PAGE as described previously (Walker et al., 2002a). Proteins were electrophoretically transferred from the gels onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and detected using standard Western Blot techniques as described previously (Walker et al., 2002a; Leonard et al., 2011). Antibodies for immunoprecipitation and/or immunoblotting included N-cadherin (BD Transduction, San Diego, CA), pSrc 416 (Biosource, Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), c-Src (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY), Fyn (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY), c-Yes (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), Lyn (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), filensin, CP49 and αA-crystallin (generous gifts from Dr. Paul Fitzgerald, University of California, Davis), and aquaporin-0 (MP28) antibody, prepared as described previously (Menko et al., 1984). Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) were detected using ECL reagent from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Immunoblots were scanned and densitometric analysis was performed using Kodak 1D software (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY). In co-immunoprecipitation studies the relative, differentiation-specific changes in the association of any specific protein with the immunoprecipitated protein was determined following densitometry analysis. The densitometry data for each protein was first normalized to one tissue fraction. This made it possible to control for differences in the antibody and HRP/ECL reactions between the multiple studies included in our statistical analysis. The averages of at least three independent studies were calculated. The ratio of the co-immunoprecipitated protein to the immunoprecipitated protein was determined and presented graphically with standard deviations.

Immunofluorescence analysis

For immunofluorescence studies chicken embryo lens cultures, ex vivo explants, or 20μ thick lens cryosections fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, were extracted with 0.25% Triton X-100 and immunostained as described previously (Walker and Menko, 1999; Leonard et al., 2011). Samples were incubated sequentially with primary antibody (N-cadherin (BD Transduction, San Jose, CA), c-Src (GD11, Millipore, Billerica, MA), Fyn (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY), phospho-Src-Y416 (Biosource, Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA), Prox1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) or phosphoHistone3 ((Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), a marker of cell proliferation), and fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). F-actin was localized with Alexa448-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes Eugene, OR). Imaging was performed by confocal microscopy analysis using a Zeiss LSM510 META confocal microscope. Z-stacks were collected and analyzed; the data presented representing a single optical plane in the Z-stack. Within each study all images with the same antibody or phalloidin labeling were acquired with the same settings.

Measurements – cell length and cell area

The length of fiber cells in the transition zone was determined in lens explants stained with fluorescent-conjugated phalloidin, which labels filamentous actin along the cell-cell borders of differentiating fiber cells. Images were acquired as Z-stacks using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. The cortical localization of actin along the borders of the elongating fiber cells was used to trace and measure the length of individual fiber cells across the different planes in the acquired Z-stacks using Zeiss LSM50 software. For each explant study 20 cell lengths were measured and the mean length of cells in the transition zone of explants grown in the presence of the Src kinase inhibitor PP1 or its vehicle DMSO determined +/− the standard error of the mean (SEM).

The area of lens epithelial cells in primary lens epithelial cell cultures was measured following a 24 hr exposure to the SFK inhibitor PP1 or its vehicle DMSO. Cultures were labeled for N-cadherin to localize the outer perimeter of the cells. Images of single optical planes were acquired with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope from which individual cell areas were measured using Zeiss LSM510 software. The areas of 40 cells were measured for each experimental condition and the mean area presented +/− the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Explant cultures following five days of exposure to the SFK inhibitor PP1 that began at culture day 1. F-actin was labeled with fluorescent-phalloidin, highlighting cell-cell borders of the elongating transition zone cells. The image is the same as the PP1-treated explant shown in Figure 4C, but at higher intensity to better delineate cell morphology.

Bullet Points.

The Src family kinase member c-Src is highly localized to nascent junctions of undifferentiated lens epithelial cells

c-Src functions as a negative regulator of N-cadherin junction maturation and lens epithelial cell differentiation initiation

A src kinase-dependent signaling pathway distinct from c-Src is required for lens fiber cell elongation and lens morphogenesis

The Src kinase Fyn, highly associated with the mature N-cadherin junctions of differentiating lens fiber cells, signals lens morphogenesis

Integration of Src family kinase signaling with N-cadherin junctions regulates lens differentiation and morphogenesis

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ni Zhai, Yim Chan, Ahmad Cader, and Iris Wolff for their excellent technical assistance, Dr. Paul FitzGerald for his generous gifts of antibodies, and Janice L. Walker and Marilyn Woolkalis for their thoughtful conversations and advice on this project.

Grant Sponsor: NIH Grants EY014258 and EY10577 to ASM; ML was supported by NIH training grant T32E5007283.

REFERENCES

- Andley UP. Crystallins in the eye: Function and pathology. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:78–98. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avizienyte E, Wyke AW, Jones RJ, McLean GW, Westhoff MA, Brunton VG, Frame MC. Src-induced de-regulation of E-cadherin in colon cancer cells requires integrin signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:632–638. doi: 10.1038/ncb829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsamo J, Arregui C, Leung T, Lilien J. The nonreceptor protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B binds to the cytoplasmic domain of N-cadherin and regulates the cadherin-actin linkage. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:523–532. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship TN, Hess JF, FitzGerald PG. Development- and differentiation-dependent reorganization of intermediate filaments in fiber cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:735–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozulic LD, Dean WL, Delamere NA. The influence of Lyn kinase on Na,K-ATPase in porcine lens epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C90–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00174.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury WJ, Davis TH, Chen C, Slat EA, Detrow MJ, Dickendesher TL, Ranscht B, Isom LL. Voltage-gated Na+ channel beta1 subunit-mediated neurite outgrowth requires Fyn kinase and contributes to postnatal CNS development in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3246–3256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5446-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga VM. Cell-cell adhesion and signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:546–556. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromann PA, Korkaya H, Courtneidge SA. The interplay between Src family kinases and receptor tyrosine kinases. Oncogene. 2004;23:7957–7968. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MT, Cooper JA. Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1287:121–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calautti E, Cabodi S, Stein PL, Hatzfeld M, Kedersha N, Paolo Dotto G. Tyrosine phosphorylation and src family kinases control keratinocyte cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1449–1465. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.6.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calautti E, Missero C, Stein PL, Ezzell RM, Dotto GP. fyn tyrosine kinase is involved in keratinocyte differentiation control. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2279–2291. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary LA, Han DC, Guan JL. Integrin-mediated signal transduction pathways. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:1001–1009. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H, Ramachandrappa S, Olsen IM, ffrench-Constant C. Integrins direct Src family kinases to regulate distinct phases of oligodendrocyte development. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:365–375. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisanti-Combes P, Lorinet AM, Girard A, Pessac B, Wasseff M, Calothy G. Effects of Rous sarcoma virus on the differentiation of chick and quail neuroretina cells in culture. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;158:115–122. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-5292-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvekl A, Duncan MK. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation during lens development. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:555–597. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan MK, Cui W, Oh DJ, Tomarev SI. Prox1 is differentially localized during lens development. Mech Dev. 2002;112:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone G, Alema S, Tato F. Transcription of muscle-specific genes is repressed by reactivation of pp60v-src in postmitotic quail myotubes. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3331–3338. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.6.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone G, Ciuffini L, Gauzzi MC, Provenzano C, Strano S, Gallo R, Castellani L, Alema S. v-Src inhibits myogenic differentiation by interfering with the regulatory network of muscle-specific transcriptional activators at multiple levels. Oncogene. 2003;22:8302–8315. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Cornwell MC, Veneziale RW, Grunwald GB, Menko AS. N-cadherin function is required for differentiation-dependent cytoskeletal reorganization in lens cells in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:237–247. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame MC. Newest findings on the oldest oncogene; how activated src does it. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:989–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame MC, Fincham VJ, Carragher NO, Wyke JA. v-Src’s hold over actin and cell adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:233–245. doi: 10.1038/nrm779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin M, Kovacs EM, Thoreson MA, Reynolds AB, Yap AS. Minimal mutation of the cytoplasmic tail inhibits the ability of E-cadherin to activate Rac but not phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: direct evidence of a role for cadherin-activated Rac signaling in adhesion and contact formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20533–20539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto J, Tezuka T, Nakazawa T, Sagara H, Yamamoto T. Loss of Fyn tyrosine kinase on the C57BL/6 genetic background causes hydrocephalus with defects in oligodendrocyte development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant SG, O’Dell TJ, Karl KA, Stein PL, Soriano P, Kandel ER. Impaired long-term potentiation, spatial learning, and hippocampal development in fyn mutant mice. Science. 1992;258:1903–1910. doi: 10.1126/science.1361685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guermah M, Gillet G, Michel D, Laugier D, Brun G, Calothy G. Down regulation by p60v-src of genes specifically expressed and developmentally regulated in postmitotic quail neuroretina cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3584–3590. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi M, Matsuyoshi N, Ohnishi Y, Gotoh B, Takeichi M, Nagai Y. p60v-src causes tyrosine phosphorylation and inactivation of the N-cadherin-catenin cell adhesion system. Embo J. 1993;12:307–314. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard M, Chan Y, Menko AS. Identification of a novel intermediate filament-linked N-cadherin/gamma-catenin complex involved in the establishment of the cytoarchitecture of differentiated lens fiber cells. Dev Biol. 2008;319:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard M, Zhang L, Zhai N, Cader A, Chan Y, Nowak RB, Fowler VM, Menko AS. Modulation of N-cadherin junctions and their role as epicenters of differentiation-specific actin regulation in the developing lens. Dev Biol. 2011;349:363–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Draghi NA, Resh MD. Signaling from integrins to Fyn to Rho family GTPases regulates morphologic differentiation of oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7140–7149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5319-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilien J, Balsamo J. The regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion by tyrosine phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of beta-catenin. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell CA, Soriano P. Knockouts of Src-family kinases: stiff bones, wimpy T cells, and bad memories. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1845–1857. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.15.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzia M, Sims NA, Voit S, Migliaccio S, Taranta A, Bernardini S, Faraggiana T, Yoneda T, Mundy GR, Boyce BF, Baron R, Teti A. Decreased c-Src expression enhances osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:311–320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyoshi N, Hamaguchi M, Taniguchi S, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. Cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion is perturbed by v-src tyrosine phosphorylation in metastatic fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:703–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan RW, Kraemer A, Helwani FM, Kovacs EM, Yap AS. E-cadherin adhesion activates c-Src signaling at cell-cell contacts. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3214–3223. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-12-1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menko AS. Lens epithelial cell differentiation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;75:485–490. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menko AS, Boettiger D. Inhibition of chicken embryo lens differentiation and lens junction formation in culture by pp60v-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1414–1420. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menko AS, Klukas KA, Johnson RG. Chicken embryo lens cultures mimic differentiation in the lens. Dev Biol. 1984;103:129–141. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menko AS, Klukas KA, Liu TF, Quade B, Sas DF, Preus DM, Johnson RG. Junctions between lens cells in differentiating cultures: structure, formation, intercellular permeability, and junctional protein expression. Dev Biol. 1987;123:307–320. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra SK, Schlaepfer DD. Integrin-regulated FAK-Src signaling in normal and cancer cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto M, Yoshimura M, Okayama M, Kaji A. Cellular transformation and differentiation. Effect of Rous sarcoma virus transformation on sulfated proteoglycan synthesis by chicken chondrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:4173–4177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Fukata M, Yamaga M, Itoh N, Kaibuchi K. Recruitment and activation of Rac1 by the formation of E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion sites. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.10.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noren NK, Niessen CM, Gumbiner BM, Burridge K. Cadherin engagement regulates Rho family GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33305–33308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterhout DJ, Wolven A, Wolf RM, Resh MD, Chao MV. Morphological differentiation of oligodendrocytes requires activation of Fyn tyrosine kinase. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1209–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.6.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa M, Ohkubo T. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p120(ctn) in v-Src transfected L cells depends on its association with E-cadherin and reduces adhesion activity. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:503–512. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza LG, Stewart RA, Li DM, Xu T. Drosophila Src-family kinases function with Csk to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Oncogene. 2004;23:4754–4762. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moreno M, Jamora C, Fuchs E. Sticky business: orchestrating cellular signals at adherens junctions. Cell. 2003;112:535–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierani A, Pouponnot C, Calothy G. Transcriptional downregulation of the retina-specific QR1 gene by pp60v-src and identification of a novel v-src-responsive unit. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3401–3414. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontoriero GF, Smith AN, Miller LA, Radice GL, West-Mays JA, Lang RA. Co-operative roles for E-cadherin and N-cadherin during lens vesicle separation and lens epithelial cell survival. Dev Biol. 2009;326:403–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relucio J, Tzvetanova ID, Ao W, Lindquist S, Colognato H. Laminin alters fyn regulatory mechanisms and promotes oligodendrocyte development. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11794–11806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0888-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roura S, Miravet S, Piedra J, Garcia de Herreros A, Dunach M. Regulation of E-cadherin/Catenin association by tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36734–36740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samayawardhena LA, Kapur R, Craig AW. Involvement of Fyn kinase in Kit and integrin-mediated Rac activation, cytoskeletal reorganization, and chemotaxis of mast cells. Blood. 2007;109:3679–3686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-057315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnekenburger J, Mayerle J, Simon P, Domschke W, Lerch MM. Protein tyrosine dephosphorylation and the maintenance of cell adhesions in the pancreas. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;880:157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzberg PL. The many faces of Src: multiple functions of a prototypical tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1998;17:1463–1468. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil SJ. Integrins and Src: dynamic duo of adhesion signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein PL, Vogel H, Soriano P. Combined deficiencies of Src, Fyn, and Yes tyrosine kinases in mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1999–2007. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.17.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda H, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Behrens J, Birchmeier W. V-src kinase shifts the cadherin-based cell adhesion from the strong to the weak state and beta catenin is not required for the shift. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1839–1847. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamiya S, Delamere NA. Studies of tyrosine phosphorylation and Src family tyrosine kinases in the lens epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2076–2081. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SM, Brugge JS. Cellular functions regulated by Src family kinases. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:513–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukropec JA, Hollinger MK, Salva SM, Woolkalis MJ. SHP2 association with VE-cadherin complexes in human endothelial cells is regulated by thrombin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5983–5986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veracini L, Franco M, Boureux A, Simon V, Roche S, Benistant C. Two functionally distinct pools of Src kinases for PDGF receptor signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:1313–1315. doi: 10.1042/BST0331313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volberg T, Geiger B, Dror R, Zick Y. Modulation of intercellular adherens-type junctions and tyrosine phosphorylation of their components in RSV-transformed cultured chick lens cells. Cell Regul. 1991;2:105–120. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]