Abstract

Background

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) include both “asymptomatic” and “symptomatic” neurocognitive impairment. Asymptomatic diagnoses indicate HAND without demonstrable functional impairment. The present study compares three approaches to assess functional decline: 1) self-report measures only (SR); 2) performance-based measures only (PB); and 3) combining SR and PB measures (SR+PB).

Methods

We assessed 674 HIV-infected research volunteers with a comprehensive neurocognitive battery; 233 met criteria for a HAND diagnosis by having at least mild neurocognitive impairment. Functional decline was measured via SR and PB measures. HAND diagnoses in these 233 cognitively impaired individuals were determined according to published criteria, which allow for both SR and PB methods in establishing functional decline.

Results

The dual-method diagnosed the most symptomatic (53%; 124/233) HAND conditions, compared to either singular method, which were only 59% concordant. Participants classified as functionally-impaired via PB were more likely to be unemployed, more immunosuppressed, and had more hepatitis-C co-infection, whereas those classified via singular SR were more depressed.

Conclusions

Multimodal methods of assessing everyday functioning facilitate detection of symptomatic HAND. PB-based classification was associated with objective functional status (i.e., employment) and important disease-related factors, whereas the typical SR singular classifications may be biased by depressed mood.

Keywords: HIV, Cognition, Assessment of Everyday Functioning, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Introduction

Despite advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) are still observed in close to half of the HIV-infected (HIV+) population (Heaton et al., 2010). It is widely held that the most prevalent form of HAND is “asymptomatic” (33% of the HIV+ population; Heaton et al., 2010), meaning that the observed neurocognitive impairment does not appear to affect daily functioning. However, research reliably demonstrates that even mild HIV-associated neurocognitive deficits, among symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, are closely associated with impaired functional outcomes, ranging from antiretroviral medication adherence (Albert et al., 1995; Benedict, R. H. B., Mezhir, J. J., Walsh, K., & Hewitt, R. G., 2000; Hinkin et al., 2002) and employment status (Benedict et al., 2000; Heaton et al., 1996) to general quality of life (Benedict et al., 2000) and mortality (Mapou et al., 1993). Such data arguably run counter to the presumed predominance of “asymptomatic” HAND and raise important questions regarding the typical self-report methods for ascertaining functional impairment.

The current nomenclature for diagnosing asymptomatic HAND (i.e., Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment; ANI) requires neurocognitive deficits in at least two ability domains that are attributable to HIV-infection, but do not meaningfully influence daily functioning (Antinori et al., 2007). In contrast, “symptomatic” HAND diagnoses require that HIV-associated deficits interfere with functional capabilities at either a mild (i.e., Mild Neurocognitive Disorder, MND) or moderate-to-severe (HIV-associated Dementia, HAD) level. The recent Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007) updated the previous HAND diagnostic standards (American Academy of Neurology, 1991), particularly by operationalizing the diagnostic criteria of “functional decline” for the symptomatic HAND levels (i.e., MND or HAD). Briefly, the diagnostic criteria continue to require neuropsychological impairment (≥ 1 standard deviation for ANI and MND; ≥ 2 standard deviations for HAD) in two or more neurocognitive domains. Additionally, the criteria specify that that mild (i.e., MND) or major (i.e., HAD) functional decline must have occurred in two or more areas (e.g., work change or decreased independence of instrumental activities of daily living, IADLs) via standardized self-report, informant-report, or performance-based measures.

Methodologically, well-validated neurocognitive assessments exist to adequately establish the presence or absence of neurcognitive impairment. The greater challenge for clinicians and researchers is in the determination of impairment in everyday functioning. Self-report measures of daily functioning have several advantages, including low cost, minimal participant burden, and high face validity (Simoni et al., 2006; Wagner & Miller, 2004). However, self-report is susceptible to social desirability and recall inaccuracies or bias, which may overestimate ability (Chesney et al., 2000; Thames et al., 2010a). For example, a recent study that examined self-report versus electronic medication event monitoring systems (MEMS) of antiretroviral medications found that self-report significantly overestimated adherence rates (self-report up to 90% adherent vs. MEMS 70% adherent; Lu et al., 2008). Additionally, self-report measures are susceptible to overestimation biases due to depressed mood; particularly in HIV+, studies have shown that depressive symptoms, not objective neuropsychological performance, accounts for a majority of the variance in cognitive and functional complaints (Rourke, Halman, & Bassel, 1999b; Thames et al., 2010b). Performance-based measures of daily functioning, on the other hand, can be time-intensive and require additional training and tools to administer (Moore, Palmer, Patterson, & Jeste, 2007), and because of their standardization may not capture differences in requirements of individual patients’ daily tasks and activities. Yet, performance-based measures utilized with HIV-infected patients have been shown to be objective and reliable in predicting “real life” outcomes such as employment status as well as medication and financial management (Heaton et al., 2004; Thames et al., 2010a).

Previous studies have established the importance of utilizing multiple assessment methods (e.g., self, informant, performance, behavioral observation) to maximize sensitivity (Hunsley & Meyer, 2003; Meyer et al., 2001; Schwartz, 1996) and increase the quality and usefulness of diagnostic information yet this approach is infrequently applied in the HIV context. Despite this, the current Frascati HAND diagnostic guidelines do not require both performance-based and self-report measures in determining level of daily functioning. In practice, clinicians and researchers often rely exclusively on self-report measures due to their convenience (e.g., Woods et al., 2004). Examining the utility of PB measures in assessing functional status is important as it may add unique diagnostic information that is currently missing when only the SR approach is applied.

Our study therefore aims to compare three functional assessment approaches to determine HAND: 1) self-report measures only (SR); 2) performance-based measures only (PB); and 3) combined self-report plus performance-based measures (SR+PB). In particular, our goal was to assess the incremental validity of the PB approach, beyond the common practice of SR, in determining functional status. We use the dual, SR+PB, classifications as the benchmark to examine the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of PB and SR alone. We hypothesized that the dual method would detect more symptomatic HAND (i.e., MND and HAD) as compared to the other approaches. Additionally, we expected that PB would be more sensitive in determining MND and HAD diagnoses than self-report, be less susceptible to depression-related reporting bias, and more strongly associated with objective indicators of disease status and functional outcomes.

Methods

Participants

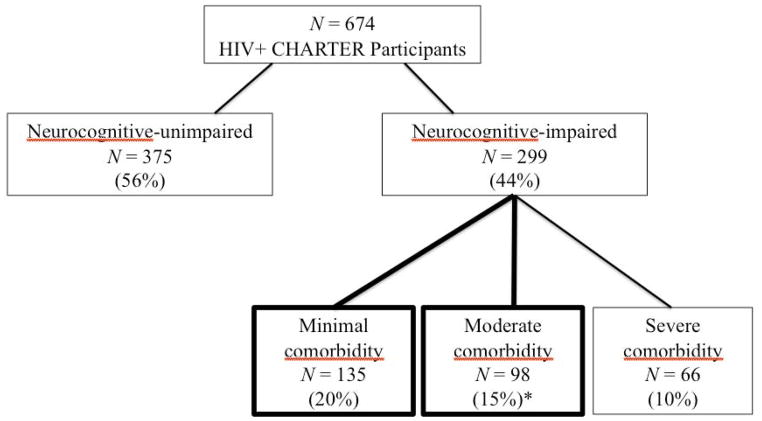

Six hundred seventy-four HIV infected (HIV+) participants were drawn from the CNS HIV Antiretroviral Therapy Research Effects (CHARTER) study, a prospective cohort study conducted in HIV clinics at six academic centers: Johns Hopkins Univeristy (Baltimore, MD); Mt. Sinai School of Medicine (New York, NY); University of California at San Diego (San Diego, CA); University of Washington (Seattle, WA); and Washington University (St. Louis, MO; see Heaton et al., 2010). All participants were HIV-infected and were excluded only if they could not complete the assessment at the time of evaluation. As the purpose of the study was to examine HAND diagnoses, only those individuals with neurocognitive impairment at entry were considered for inclusion in the analyses (44% of the cohort; 299/674). Of these, most (45%, 135/299) were classified as having none or minimal comorbidities (non-HIV related factors that could affect cognition and functioning) and 33% (98/299) with moderate comorbidities. Those with severe comorbidities (22%, 66/299) that precluded a HAND diagnosis were excluded (see Table 4 of the E2 online supplement from Antinori et al., 2007 for comorbid classification assignment). Analyses were therefore focused on the 233 participants identified as having HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment restricted to minimal or moderate comorbidities (see Figure 1). The demographic, psychiatric, and HIV disease and treatment characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow chart indicating participant selection procedure; boxes in bold signify those subjects included in analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics (n = 233).

| Demographic variable | M, P, or Median | SD or IQR | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45.2 | 8.5 | 22 – 69 |

| Education, years | 13.3 | 2.4 | 7 – 20 |

| Gender (M) | 77% | ---- | ---- |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 44% | ---- | ---- |

| African-American | 39% | ---- | ---- |

| Hispanic | 14% | ---- | ---- |

| Other | 3% | ---- | ---- |

| Current CD4 (cells/μL) | 451 | 168 – 626 | ---- |

| Nadir CD4 (cells/μL) | 150 | 43 – 275 | ---- |

| AIDS | 64% | ---- | ---- |

| % HIV CSF viral load detectable | 25% | ---- | ---- |

| % detectable if on ARVs | 56% | ---- | ---- |

| % HIV plasma viral load detectable | 46% | ---- | ---- |

| % detectable if on ARVs | 73% | ---- | ---- |

| Hepatitis C virus co-infection | 23% | ---- | ---- |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | 12.6 | 11.1 | 0 – 56 |

| Employed | 33% | ---- | ---- |

| LT substance abuse/dependence dx | 67% | ---- | ---- |

Abbreviations: M = mean; P = percent; SD = standard deviation; IQR = Inter-quartile range; ARVs = antiretrovirals; LT substance abuse/dependence dx = DSM-IV diagnosis of lifetime substance abuse or dependence

Procedures

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Participant Consents

The Human Subjects Protection Committees of each participating institution approved the study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Laboratory Assessment

HIV infection was diagnosed by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay with Western blot confirmation. Routine clinical chemistry panels, complete blood counts, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C virus antibody, and CD4+ T cells (flow cytometry) were performed at each site’s Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified, or CLIA equivalent, medical center laboratory. HIV RNA levels were measured centrally in plasma and CSF by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Roche Amplicor, v. 1.5, lower limit of quantitation 50 copies/mL). AIDS was diagnosed using available clinical and immunologic data (defined as has having a CD4 Cell Count < 200 cells/μL or the presence of an AIDS-indicating clinical conditions utilizing the CDC AIDS classification system).

Neurobehavioral Examination

All participants completed a comprehensive neurocognitive test battery, covering seven ability domains commonly affected by HIV-associated CNS dysfunction (see Heaton et al., 2010 for listing of specific tests). Raw test scores were converted to demographically-corrected standard scores (T-scores). The best available normative standards were used, which correct for effects of age, education, sex and ethnicity, as appropriate (Heaton, Taylor, Manly & Tulsky, 2003; Heaton et al., 2004; Norman et al., in press). For a small subset of the neurocognitive tests, the six-month data reported here was the third testing exposure due to the administration of a brief screening and baseline assessment; however, we adjusted for practice effects of a single exposure because of complications in applying differential corrections to different tests. Therefore, T-scores were corrected for practice effects from the baseline visit using a regression-based approach (Cysique et al., in press). To classify presence and severity of neurocognitive impairment, we applied a published objective algorithm that has been shown to yield excellent interrater reliability in previous multisite studies (Woods et al., 2004). These clinical ratings of NP function were assigned for each of the seven major ability areas as well as a global NP clinical rating, using a 9-point scale (1=above average functioning to 9 = severe impairment) with a global rating of 5 or above indicating abnormal NP functioning (Antinori et al., 2007; Woods et al., 2004).

Psychiatric examination

Psychiatric and substance abuse or dependence DSM-IV diagnoses were assessed by administering the Depression and Substance Use modules of the computer-assisted Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; World Health Organization, 1997). Current mood was assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, 1996).

Functional impairment in everyday life

Self-report measures

The Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory was administered to determine perceived everyday functioning (PAOFI; Chelune, 1986). The PAOFI is a 41-item questionnaire in which the participant reports the frequency with which he/she has difficulties with memory, language and communication, use of his/her hands, sensory-perception, higher level cognitive and intellectual functions, work and recreation.

To assess dependence in performing instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), a modified version of the Lawton and Brody scale was utilized (Heaton et al., 2004). This scale includes 13 items detailing the degree to which individuals independently function in the areas of Financial Management, Home Repair, Medication Management, Laundry, Transportation, Grocery Shopping, Comprehension of Reading, TV Materials, Shopping, Housekeeping (Cleaning), Cooking, Bathing, Dressing, and Telephone Use. For each activity the participant separately rates his/her current level of independence and highest previous level of independence. The total score is the total number of activities for which there is currently a need for increased assistance (ranging from minimal to complete assistance), with a range of zero (no change) to 13 (increased dependence in all activities).

Performance-based measures

Medication management was assessed via a revised version of The Medication Management Test (Albert et al., 1999). A full description of our modified version of the MMT can be found in Heaton et al. (2004). Briefly, the MMT-R retains the pill-dispensing component in which subjects must dispense a one-day dosage of “medications” from three standardized bottles labeled with dosing information. In the medication inference component, there are seven questions regarding the medications as well as an over-the-counter medication insert. The MMT-R takes approximately 10 minutes to administer and the best score possible is10 points.

Participants also completed standardized work samples (MESA SF2) and the next generation COMPASS programs (Valpar International Corporation, 1986, 1992). These batteries consist of multi-modal, criterion-referenced instruments designed to establish participant skill level in areas of vocational functioning. The battery takes approximately one-hour and includes computerized subtests and noncomputerized mechanical tasks that correspond to the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT; U.S. Department of Labor, 1991) job levels. Raw scores from these tests are converted into ability levels for each of the DOT classifications using the commercial software accompanying the MESA SF2 and COMPASS. A detailed explanation of test development for the MESA and COMPASS is beyond the scope of this paper (see Valpar International Corporation, 1986, 1992; Heaton et al., 2010).

Performance-based measures cut-points

Since published demographically-adjusted normative standards are not available for the performance-based tests, we derived cut-points for the MMT-R and Valpar from the HIV+, NP-normal subset of CHARTER participants (n = 375; mean age = 43.4 (8.5) years; 80% M; 42% Caucasian; mean education = 12.5 years). Based on prior studies (e.g., Heaton et al., 2004), cut-points were determined based on a normal distribution so that 16% of the NP-normal cohort would be impaired at one standard deviation (cutoff scores: MMT-R < 5 and Valpar < 24) and 2% of the cohort would be impaired at two standard deviations (cutoff scores: MMT-R < 2 and Valpar < 17).

HAND Classifications

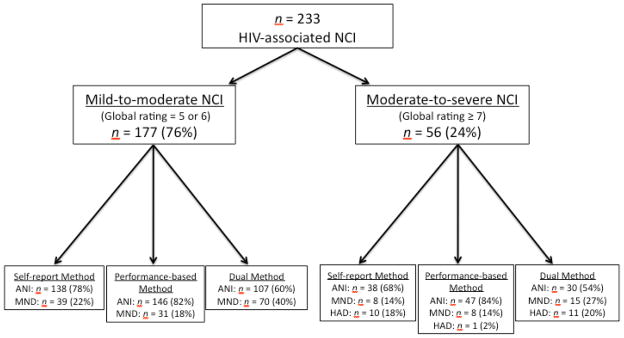

For the purposes of this study, the authors created data-driven formulas to diagnose ANI, MND and HAD three distinct ways: 1) utilizing only the self-report measures of daily functioning (SR); 2) utilizing only the performance-based measures of daily functioning (PB); and 3) combining both the self- and performance-based measures of daily functioning (SR+PB). In all formulas, an NP global rating score of 5 or 6 defined mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment (i.e., minimum criteria needed for ANI or MND; see Figure 2) and an NP global rating score of 7 or above defined moderate-to-severe cognitive impairment (i.e., minimum criteria needed for HAD). Additionally, employment status (i.e., unemployed) counted as one area of functional decline in all formulas in accordance with the Frascati criteria (Antinori et al., 2007). To determine functional decline in the SR formula, scores on the PAOFI and IADL were examined. Specifically, impairment on the PAOFI was established according to the guidelines outlined by Woods et al. (2004) such that the presence of three or more items endorsed as “almost always,” “very often,” or “fairly often” indicated areas of functional impairment. In order to control for depression in self-report, previously defined criteria were used (Woods et al., 2004) in which subjects with elevated BDI scores (BDI ≥ 17) needed to exhibit a higher level of complaint on the PAOFI (PAOFI ≥ 10 complaints), in order to qualify for functional impairment on this measure. Scores on the IADL that show decline from “best” to “now” in two or more areas that were identified as being at least partially due to cognitive problems (versus physical impairment) also qualified as one area of functional decline in the SR formula (Woods et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

HAND classification flow chart via the self-report, performance-based, and dual assessment approaches. Definitions and abbreviations: NCI = neurocognitive impairment; ANI = Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment; MND = Mild Neurocognitive Disorder; HAD = HIV-Associated Dementia; Mild-to-moderate NCI: global rating = 5 or 6; Moderate-to-severe NCI = global rating ≥ 7.

In the PB formula, mild and major functional impairment were defined as scores one or two standard deviations below the mean, respectively, on the MMT-R and Valpar in line with the Frascati criteria. Therefore, MND was diagnosed if both MMT-R and Valpar scores were one standard deviation below the mean or if one task was one standard deviation below the mean and the subject was unemployed. HAD was diagnosed: 1) if both MMT-R and Valpar scores were two standard deviations below the mean; 2) if scores on both tasks were one standard deviation below the mean and the subject was unemployed; or 3) if one task was two standard deviations below the mean and the subject was unemployed.

All diagnostic criteria for functional decline were included in the dual diagnostic method (SR+PB). Measures included in each formula criterion are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria for measures included in each diagnostic formula.

| Formula | NP Global Rating | PAOFI | IADL | MMT-R | Valpar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Report | ≥ 5 = cognitive impairment | ≥ 3 elevated items | ≥ 2 areas of decline | ||

| Performance-Based | ≥ 5 = cognitive impairment | < 5 = mild imp; < 2 = mod imp | < 24 = mild imp; < 17 = mod imp | ||

| Dual method | ≥ 5 = cognitive impairment | ≥ 3 elevated items | ≥ 2 areas of decline | < 5 = mild imp; < 2 = mod imp | < 24 = mild imp; < 17 = mod imp |

Abbreviations: NP = neuropsychological; PAOFI = Patient’s Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; MMT-R = Medication Management Test-Revised; mild imp = mild impairment (below 1 SD); mod imp = moderate impairment (below 2 SDs). Note: employment status was also included in the diagnostic formulas and additional modifications were made for individuals with significant depression, see text.

Discrepancy variable

Discordant classifications between the SR and PB methods were examined by creating a “discrepancy variable” with four levels: 1) agree: asymptomatic (i.e., ANI); 2) agree: symptomatic; 3) discrepant: functionally impaired by SR only; and 4) discrepant: functionally impaired by PB only. The discrepancy variable was used to examine potential demographic, disease, psychiatric, and cognitive differences that may be associated with discordant diagnoses.

Statistical analyses

The McNemar-Bowker nonparametric test for non-independent samples was conducted to compare HAND diagnosis frequencies (i.e., ANI vs. MND. vs. HAD) as well as “syndromic” frequencies (i.e., MND or HAD) across each diagnostic method (SR, PB, and SR+PB). Sensitivity and specificity of the singular methods (i.e., SR and PB) compared to the dual method were calculated for each diagnostic level (i.e., ANI vs. MND+HAD; ANI+MND vs. HAD; and ANI vs. MND). Chi-square analyses were conducted to compare the sensitivity and specificity of the SR versus PB methods across each specified diagnostic level.

The discrepancy variable (described above) was explored by screening which disease and functional variables significantly predicted the discrepancy variable at a 10% significance level in a multivariable logistic regression. Only those variables remaining were again entered together in the multivariable logistic regression with discrepancy variable as the outcome. Each of the variables remaining in the model were then tested individually for differences between the “only PB functionally impaired” and the “only SR functionally impaired” levels of the discrepancy variable.

Additional analyses explored the relationship between scores on the individual SR and PB measures to self-reported depressive symptoms (i.e., BDI) using nonparametric Spearman’s correlations.

Results

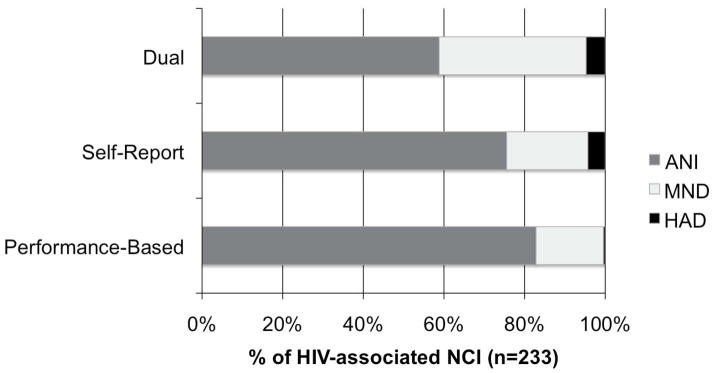

HAND diagnoses frequencies across SR, PB, and SR+PB methods

As shown in Figure 3, the SR+PB method yielded the lowest prevalence of ANI diagnoses at 47% as compared to 67% with the PB method (χ2 = 48; kappa = .60; p < .001) and 75% with the SR approach (χ2 = 65; kappa = .46; p < .001). Each of the three diagnostic methods yielded a different prevalence of MND diagnoses; the dual approach detected the most at 47% as compared to 32% with the PB method (χ2 = 31.8; kappa = .62; p<.001), and 19% with the SR method (χ2 = 63; kappa = .44; p < .001). The PB method also classified a higher proportion of MND than the SR method (32% vs.19% respectively; χ2 = 7.9; kappa = .06; p = .005). PB yielded the least number of HAD diagnoses at 1% compared to SR (X2 = 6.2; kappa = .11; p = .01) and the dual method (χ2 = 11; kappa = .34; p < .001) which were comparable in their number of HAD diagnoses at 6%. Similarly, the dual method diagnosed the most syndromic cases (i.e., MND or HAD) at 53% compared to the PB approach at 33% (χ2 = 48; kappa = .60; p < .001) or the SR approach at 25% (χ2 = 65; kappa = .46; p < .001). Among the sympotmatic diagnoses, there was an additive effect between each of the singular diagnoses (SR = 25% and PB = 33% syndromic) to comprise the dual diagnoses (SR+PB = 53%) suggesting that there are not many overlapping syndromic diagnoses across each of these singular methods.

Figure 3.

The Dual classification method yielded the lowest prevalence of ANI and largest prevalence of symptomatic diagnoses compared to either singular method. Each row represents the proportion of specific HAND diagnoses by assessment method among the participants with HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment. Abbreviations: NCI = neurocognitive impairment; ANI = Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment; MND = Mild Neurocognitive Disorder; HAD = HIV-associated Dementia.

Sensitivity and specificity of the singular methods compared to the dual method

Using the dual method as the “benchmark” to compare the singular methods against, PB diagnoses were more sensitive in detecting MND vs. ANI diagnoses than the SR method (60% vs. 42% respectively; χ2 = 6.9, p = .009). The PB method was also more sensitive than the SR method in determining MND+HAD versus ANI diagnoses (61% vs. 48% respectively; χ2 = 4.0, p = .046). Lastly, the SR method was more sensitive in detecting HAD versus ANI+MND (i.e., non-HAD) diagnoses than the PB method (86% vs. 21%; χ2 = 11.6, p < .001). Specificity (i.e., proportion of individuals that are correctly identified as functionally unimpaired) across all of the different HAND levels was comparable between the SR and PB methods (MND vs. ANI: 100% vs. 100%; and MND+HAD vs. ANI: 100% vs. 97%; all p’s > .05).

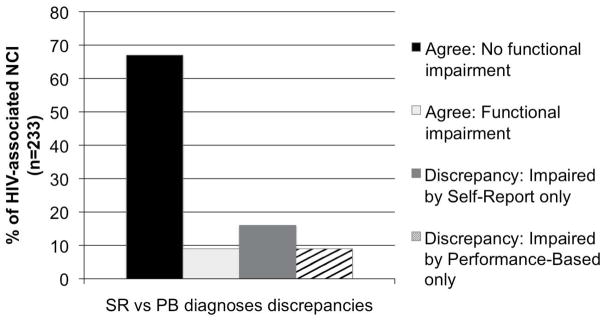

Discrepant singular diagnoses

When examining the discrepant variable (i.e., discordant singular classifications) across demographic and clinical variables of interest, current CD4, HCV status, BDI, and employment status predicted the discrepancy variable at p < .10. In the multivariable analysis, all of these predictor variables uniquely contributed to discrepant diagnoses (see Table 3). Specifically, the PB functionally impaired participants were less likely to be employed (χ2 = 25.2, p < .001), endorsed fewer depressive symptoms (χ2 = 15.4, p < .001), had lower current CD4 counts (χ2 = 9.5, p = 0.002), and higher rates of hepatitis C co-infection (χ2 = 5.7, p = .02) than the SR functionally impaired. See Figure 4 for discrepant diagnosis frequencies.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model predicting four-level discrepancy variable: 1) agree: asymptomatic; 2) agree: symptomatic; 3) discrepant: functionally impaired by Self-Report only; 4) discrepant: functionally impaired by Performance-Based only.

| Variable | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Multivariable logistic regression model. Overall model: R2 = 0.27, χ2 = 102.9, p < 0.001 | ||

| Age† | 6.8 | 0.08 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian vs. other) † | 6.8 | 0.08 |

| Education† | 6.9 | 0.08 |

| Gender | 0.80 | 0.85 |

| Current CD4† | 8.5 | 0.04 |

| AIDS | 0.55 | 0.91 |

| Log10 HIV RNA (CSF) | 2.9 | 0.41 |

| Log10 HIV RNA (plasma) | 2.7 | 0.43 |

| HCV status† | 6.8 | 0.08 |

| BDI-II† | 27.9 | < 0.001 |

| LT substance abuse | 4.4 | 0.21 |

| Employment† | 20.3 | < 0.001 |

| Global NP T-score | 0.37 | 0.95 |

| Step 2: Multivariable logistic regression model with significant (p < .10) predictors. Overall Model: R2 = 0.46, χ2 = 59.45, p < 0.001 | ||

| Age* | 8.2 | 0.04 |

| Ethnicity* | 9.1 | 0.03 |

| Education | 5.5 | 0.14 |

| Current CD4* | 14.6 | 0.002 |

| HCV status† | 6.30 | 0.10 |

| BDI-II* | 28.8 | < 0.001 |

| Employment* | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05.

Abbreviations: HCV = Hepatitis C co-infection; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; LT = lifetime; NP = neuropsychological

Figure 4.

Frequency of discrepant Self-Report versus Performance-Based classifications. Agree: No functional impairment = 67% (156/233); Agree: Functional impairment = 9% (20/233); Discrepancy: Impaired by Self-Report only = 16% (37/233); Discrepancy: Impaired by Performance-Based only = 9% (20/233). Abbreviations: NCI = neurocognitive impairment.

Within the concordant diagnoses between the singular methods, the asymptomatic agreement group endorsed fewer depressive symptoms (χ2 = 17.3, p < 0.001) than the symptomatic agreement group, as expected.

Depression

As depressive symptoms have been shown to be highly associated with functional status and can particularly influence self-reported functioning, we examined the relationship of Beck Depression Inventory scores to all of the functional measures (Rourke, Halman, & Bassel, 1999b; Thames et al., 2010b). Both of the SR measures were correlated to BDI scores (IADL: ρ = 0.46, p < .001; PAOFI: ρ = 0.53, p < .001). Neither of the PB measures was correlated to BDI scores (Valpar: ρ = −0.02, p > .05; MMT-R: ρ = 0.05, p > .05).

Discussion

We found modest (59%) concordance between the SR and PB methods in classifying functional impairment. Of the two methods, PB classified more participants as being functionally impaired, however, 17% of the sample was still classified as impaired via SR but not PB. Our only objective “gold standard” indicator of everyday functioning was employment status, and individuals who were classified as functionally impaired only by PB were more likely to be unemployed than those who were called functionally impaired only by SR. In addition, PB only impaired participants had more severe disease indicators (current degree of immunosuppression and co-infection with the Hepatitis C virus, which can also cause CNS dysfunction and cognitive impairment; Thannoun & Quinn, 1996; Garrido er al., 2009). These findings support the validity of the PB measures over the SR measures in being able to detect “real life” constructs that are theoretically important to functional status.

By contrast, participants who were classified as functionally impaired by SR-only showed more depressive symptoms, which are known to be associated with negative self-image and a tendency to over-report impairment (Rourke et al., 1999b; Thames et al., 2010b). Depressive symptoms were to some extent accounted for in the SR classification in that those individuals with elevated depression scores (BDI ≥ 17) need to have substantially more complaints (PAOFI ≥ 10) in order to meet HAND criteria. Therefore, despite a restricted BDI range, the effect of mild depression was still captured in the SR diagnoses. The influence of depression in the SR classifications that is absent in the PB classifications illustrates the powerful effect of depression on complaints and, subsequently, how a belief of impairment can influence diagnosis. The potential impact of depression in determining self-reported functional status highlights the importance of taking affective state into account when determining HAND classifications based on self-report.

On the other hand, since those individuals classified as functionally impaired by SR-only appeared to have more functionally complex lives (i.e., more likely to be employed and less disease severity), the importance of any decline may have impacted the number and severity of reported complaints relative to expectations in their lives. In other words, those with the most complicated lives had the most to lose functionally and were, therefore, more likely to complain of these changes. Self-report measures inherently control for variables relative to individual (e.g., perceived premorbid functioning and life expectations), and therefore reflect the individual’s inability to complete tasks specific to his or her own life. Although PB measures do not account for the subjective relevance of functional decline, they do standardize impairment so that individual performances can be equally compared to each other. In this manner, the PB approach provides a standard diagnostic of impairment for each HAND level thereby improving the ability for clinicians and researchers to communicate with common understanding.

An important limitation of the current study is the use of the dual diagnostic method to compare the singular methods when the dual method is just a composite of both of the singular methods together. As such, an association between the singular and dual methods is anticipated, and the true sensitivity and specificity of each of the singular methods to real life HAND diagnoses is not clear. Ideally, the SR and PB methods should be compared to an independent measure of daily functioning, such as a clinician’s rating, informed proxy report, or an objective outcome measure (e.g., medication blood levels as an indicator of adherence). Additionally, it is important to note that each of the three formulas for HAND classifications were purely data-driven--clinical input is an integral aspect in determining HAND diagnoses and should always be incorporated in addition to the available data. Lastly, the use of employment as an objective measure of functional status is problematic due to the potential motives unrelated to cognitive status that can explain unemployment, especially in the context of advanced HIV disease. For example, individuals that qualify for disability (particularly physical disability) may have the cognitive capacity to be employed but are unable to work because of physical limitations. As such, our results in relation to employment must be interpreted with caution.

To summarize, findings from this study indicate that incorporating information from functional PB measures in addition to the traditional SR approach detects more impairment; utilizing either SR or PB measures alone may underestimate functional impairment. Although SR measures are able to account for relative demands in daily life, PB measures standardize deficits onto a comparable scale and, importantly, may be most predictive of true disease and functional status. Another benefit of the PB approach is the measures’ lack of relationship to depressive symptoms. As such, PB measures are a useful and valid component of functional assessments, which are likely to enhance the accuracy of symptomatic HAND classifications (beyond SR only). Of note, however, PB measures do take more time and training than SR which may not be practical in many clinical settings; nonetheless, clinicians and researchers should be aware that use of SR only is likely to both underclassify symptomatic HAND and result in some false positive diagnoses due to depression-related biases in self-evaluations. Overall, our findings support the time and resources necessary to incorporate PB measures in addition to the traditional SR-approach when assessing functional status in individuals with HIV+. Future studies should focus on specifically which PB measures may be most representative and predictive of functional impairment as well as how these measures can be best incorporated into clinical assessment of individuals with HIV+.

Acknowledgments

The CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) is supported by award N01 MH22005 from the National Institutes of Health.

* The CNS HIV Anti-Retroviral Therapy Effects Research (CHARTER) group is affiliated with the Johns Hopkins University, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, University of Texas, Galveston, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington University, St. Louis and is headquartered at the University of California, San Diego and includes: Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Center Manager: Donald Franklin, Jr.,.; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Terry Alexander, R.N.; Laboratory, Pharmacology and Immunology Component: Scott Letendre, M.D. (P.I.), Edmund Capparelli, Pharm.D.,; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D., Matthew Dawson; Virology Component: Joseph K. Wong, M.D. (P.I.); Imaging Component: Terry Jernigan, Ph.D. (Co-P.I.), Michael J. Taylor, Ph.D. (Co-P.I.), Rebecca Theilmann, Ph.D.; Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman,; Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Christopher Ake, Ph.D., Florin Vaida, Ph.D.; Protocol Coordinating Component: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D. (P.I.), Rodney von Jaeger, M.P.H.; Johns Hopkins University Site: Justin McArthur (P.I.), Gilbert Mbeo, MBChB; Mount Sinai School of Medicine Site: Susan Morgello, M.D. (Co-P.I.) and David Simpson, M.D. (Co-P.I.), Letty Mintz, N.P.; University of California, San Diego Site: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D. (P.I.), Susan Ueland, R.N.; University of Washington, Seattle Site: Ann Collier, M.D. (Co-P.I.) and Christina Marra, M.D. (Co-P.I.), Trudy Jones, M.N., A.R.N.P.; University of Texas, Galveston Site: Benjamin Gelman, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), Eleanor Heckendorn, R.N., B.S.N.; and Washington University, St. Louis Site: David Clifford, M.D. (P.I.), Muhammad Al-Lozi, M.D., Mengesha Teshome, M.D.

The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center (HNRC) is supported by Center award MH 62512 from NIMH.

*The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center [HNRC] group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and J. Allen McCutchan, M.D.; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, M.P.H.; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D. (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., Scott Letendre, M.D., Edmund Capparelli, Pharm.D., Rachel Schrier, Ph.D., Terry Alexander, R.N., Debra Rosario, M.P.H., Shannon LeBlanc; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (P.I.), Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D., Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., David J. Moore, Ph.D., Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Terry Jernigan, Ph.D. (P.I.), Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., Sarah L. Archibald, M.A., John Hesselink, M.D., Jacopo Annese, Ph.D., Michael J. Taylor, Ph.D.; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, M.D. (P.I.), Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D., Ian Everall, FRCPsych., FRCPath., Ph.D. (Consultant); Neurovirology Component: Douglas Richman, M.D., (P.I.), David M. Smith, M.D.; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, M.D., (P.I.); Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, M.D., Ph.D.; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (P.I.), Rodney von Jaeger, M.P.H.; Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (P.I.), Clint Cushman (Data Systems Manager); Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (P.I.), Florin Vaida, Ph.D., Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., Anya Umlauf, M.S., Tanya Wolfson, M.A.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

References

- Albert S, Marder K, Dooneief G, Bell K, Sano M, Stern Y. Neuropsychologic impairment in early HIV infection: A risk for work disability. Archives of Neurology. 1995;52:525–530. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540290115027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert S, Weber CM, Todak G, Polanco C, Clouse R, McElhiney M, Marder K. An observed performance test of medication management ability in HIV: Relation to neuropsychological status and medication outcomes. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Neurology. Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurologic manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Neurology. 1991;41:778–785. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, Mezhir JJ, Walsh K, Hewitt RG. Impact of human immunodeficiety virus type-1-associated cognitive dysfunction on activities of daily living and quality of life. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2000;15:535–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chelune GJ, Heaton RK, Lehman RA. Neuropsychological and personality correlates of patients complaints of disability. New York: Plenum Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu A. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cysique LA, Franklin D, Abramson I, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Collier A, Heaton RK. Normative data and validation of a regression based summary score for assessing meaningful neuropsychological change. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1:1–18. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.535504. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarli C. Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence, prognosis, aetiology, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2003;2(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detels R, Munoz A, McFarlane G, Kingsley LA, Margolick JB, Giorgi J, Phair JP. Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(17):1497–1503. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.17.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr MC, Heaton RK, Miller W, Grant I. The Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT): norms for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1998;5(4):375–387. doi: 10.1177/107319119800500407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido JMF, Alvarez MR, Castro JL, Lopez MAS. Neuropsychological performance in patients with human immunodeficiency (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection. Neurologia. 2009;24:154–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladsjo JA, Schuman CC, Evans JD, Peavy GM, Miller SW, Heaton RK. Norms for letter and category fluency: demographic corrections for age, education, and ethnicity. Assessment. 1999;6(2):147–178. doi: 10.1177/107319119900600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goverover Y, Chiaravalloti N, Gaudino-Goering E, Moore N, DeLuca J. The relationship among performance of instrumental activities of daily living, self-report of quality of life, and self-awareness of functional status in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54(1):60–68. doi: 10.1037/a0014556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK. Comprehensive norms for an expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: A supplement for the WAIS-R. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Grant I for the CHARTER Group. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Grant I, Butters N, White DA, Kirson D, Atkinson JH, Abramson I The HNRC Group. The HNRC 500--neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 1995;1(3):231–251. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Grant I, Matthews CG. Comprehensive norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographic corrections, research findings, and clinical applications. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Mindt MR, Sadek J, Moore DJ, Bentley H, Grant I The HNRC Group. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004;10(3):317–331. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, White DA, Ross D, Meredith K, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Nature and vocational significance of neuropsychological impairment associated with HIV infection. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1996;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Taylor MJ, Manly J, Tulsky DS. Clinical Interpretation of the WAIS-III and WMS-III. Burlington: Academic Press; 2003. Demographic effects and use of demographically corrected norms with the WAIS-III and WMS-III; pp. 181–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Hardy DJ, Lam MN, Mason KI, Stefaniak M. Medication adherence among HIV+ adults: Effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1944–1950. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038347.48137.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, Meyer GJ. The incremental validity of psychological testing and assessment: conceptual, methodological, and statistical issues. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15(4):446–455. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly JB, Wherry JN, Wiesner DC, Reed DH, Rule JC, Jolly JM. The mediating role of anxiety in self-reported somatic complaints of depressed adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22(6):691–702. doi: 10.1007/BF02171996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karagiozis H, Gray S, Sacco J, Shapiro M, Kawas C. The direct assessment of functional abilities (DAFA): A comparison to an indirect measure of instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1998;38(1):113–121. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBuda J, Lichtenberg P. The role of cognition, depression, and awareness of deficit in predicting geriatric rehabilitation patients’ IADL performance. Clinical Neuropsychology. 1999;13(3):258–267. doi: 10.1076/clin.13.3.258.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leifer BP. Early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: clinical and economic benefits. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2003;51(5 Suppl Dementia):S281–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.5153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, Rogers WH, Coady W, Hardy H, Wilson IB. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behavior. 2008;12(1):86–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9261-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapou RL, Law WA, Martin A, Kampen D, Salazar AM, Rundell JR. Neuropsychological performance, mood, and complaints in cognitive and motor difficulties in individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Neuropsychiatric Clinical Neuroscience. 1993;5:86–93. doi: 10.1176/jnp.5.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer GJ, Finn SE, Eyde LD, Kay GG, Moreland KL, Dies RR, Reed GM. Psychological testing and psychological assessment. A review of evidence and issues. The American Psychologist. 2001;56(2):128–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Palmer BW, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. A review of performance-based measures of functional living skills. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41(1–2):97–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman MA, Moore DJ, Taylor MJ, Franklin D, Cysique L, Ake C, Heaton RK. Demographically corrected norms for African Americans and Caucasians on the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, Stroop Color and Word Test, and Wisconsin Card Sorting Test 64-Card Version. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.559157. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor V, Murphy J, Mastersonallen S, Willey C, Razmpour A, Jackson ME, Katz S. Risk of Functional Decline among Well Elders. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1989;42(9):895–904. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM, Medina A. Cross-cultural sensitivity in assessment. Using tests in culturally appropriate ways. In: Suzuki LA, Meller PJ, Ponterotto JG, editors. Handbook of Multicultural Assessment: Clinical, Psychological, and Educational Applications. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1996. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56(9):1133–1142. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putzke JD, Williams MA, Daniel FJ, Bourge RC, Boll TJ. Self-report versus performance-based activities of daily living capacity among heart transplant candidates and their caregivers. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2000;7(2):121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Rourke SB, Halman MH, Bassel C. Neuropsychiatric correlates of memory-metamemory dissociations in HIV-infection. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1999a;21(6):757–768. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.6.757.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rourke SB, Halman MH, Bassel C. Neurocognitive complaints in HIV-infection and their relationship to depressive symptoms and neuropsychological functioning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1999b;21(6):737–756. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.6.737.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CE, Kozora E, Zeng Q. Towards patient collaboration in cognitive assessment: Specificity, sensitivity, and incremental validity of self-report. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18(2):177–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02883395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg MJ, Wegner SA, Milazzo MJ, McKaig RG, Williams CF, Agan BK, Dolan MJ for the Tri-service AIDS Clinical Consortium Natural History Study Group. Effectiveness of highly-active antiretroviral therapy by race/ethnicity. AIDS. 2006;20(11):1531–1538. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000237369.41617.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: A review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behavior. 2006;10(3):227–245. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames AD, Kim MS, Becker BW, Foley JM, Hines LJ, Singer EJ, Hinkin CH. Medication and finance management among HIV-infected adults: The impact of age and cognition. Journal of Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010a:1–10. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.499357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames AD, Becker BW, Marcotte TD, Hines LJ, Foley JM, Ramezani A, Hinkin CH. Depression, cognition, and self-appraisal of functional abilities in HIV: An examination of subjective appraisal versus objective performance. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2010b:1–20. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.539577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannoun AS, Quinn PG. Reversible neurological deficit and redual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) abnormalities led to diagnosis of chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:A1344–A1344. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Dictionary of occupational titles. 4. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Valpar International Corporation. Microcomputer Evaluation and Screening Assessment (MESA) Short Form 2. Tucson, AZ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Valpar International Corporation. Computerized Assessment (COMPASS) Tuscon, AZ: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G, Miller LG. Is the influence of social desirability on patients’ self-reported adherence overrated? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(2):203–204. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200402010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Carey CL, Moran LM, Dawson MS, Letendre SL, Grant I. Frequency and predictors of self-reported prospective memory complaints in individuals infected with HIV. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2007;22(2):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Frol AB, Levy JK, Ryan E, Soukup VM, Heaton RK. Interrater reliability of clinical ratings and neurocognitive diagnoses in HIV. Journal of Clinical Experimental Neuropsychology. 2004;26(6):759–778. doi: 10.1080/13803390490509565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]