Abstract

The cytoplasm of living cells responds to deformation in much the same way as a water-filled sponge does. This behaviour, although intuitive, is connected to long-standing and unsolved fundamental questions in cell mechanics.

We often think of the cell as being an astounding machine. Indeed, the cell has the capabilities to contract, stiffen, stretch, fluidize, reinforce, crawl, intravasate, extravasate, invade, engulf, divide, swell, shrink or remodel. This impressive mechanical repertoire can generate changes in cell shape, size, or both, which can be comparable to the dimensions of the cell itself. However, the metaphor of cell as machine is in several regards misleading. Unlike machines, cells do not have specialized components connected to only a few other components and designed specifically to perform only one distinct function. Rather, connections are established by a limited number of components (such as genes and proteins) to perform multiple cellular functions. As such, the notion of cell as machine may lead to misunderstandings about how the eukaryotic cell actually works, down to the level of the gene, and even how the earliest eukaryotic cells came to be.

One key function of the eukaryotic cell is deformability, which is well characterized phenomenologically yet remains poorly understood fundamentally. When the cell is at rest, molecular fluctuations within its cytoskeletal network are not dominated by thermal fluctuations — as in colloidal materials at equilibrium and as assumed in traditional theories of viscoelasticity — but rather by the ongoing hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which releases about 20 thermal units of energy per hydrolysis event. Einstein's fluctuation–dissipation theorem (which relates a system's fluctuations at thermal equilibrium and its response to external perturbations) and anything that depends on it thus fail dramatically1,2. Moreover, for imposed strains of about 1% or smaller, the rheology of the cytoskeleton is strongly coupled to the active contractile stresses that it generates3, is highly sensitive to water content and the associated molecular crowding4, and is described universally by weak power laws. Therefore, cell rheology cannot be characterized by any defined scale of time5. Furthermore, for the larger deformations that characterize most of the physiological range, the cytoskeleton undergoes a remarkable transition from a solid-like to a fluid-like state6. The cell's nucleus, which is stiffer than the cytoskeleton, also shares some of these same features7. Importantly, it is well recognized that these elastic cellular structures are porous and dispersed in water, which is of course the principal cellular constituent. Still, although the implications of water flow on cellular mechanics are known to be important4, the underlying mechanism has never been clear.

Writing in Nature Materials, Moeendarbary and colleagues provide key clarifying insights. Using a combination of experiment and theory, they demonstrate that if an imposed cellular deformation is both big and fast enough to generate an appreciable change in local cytoplasmic volume, then the local restoring force that the cell generates can be understood as arising from poroelasticity8, that is, the redistribution of a viscous fluid flowing through a porous elastic matrix (Fig. 1) as occurs in the wringing of a water-filled sponge. Indeed, the authors show that, for a volume change of about 10 μm3, poroelasticity dominates for events faster than roughly 0.5 s. If E is cytoskeletal elasticity, ξ is pore size and μ is cytosolic viscosity, then these fast events are characterized by a poroelastic diffusion constant Dp that scales as Dp ~ Eξ2/μ. Importantly, each of these three parameters carries a clear physical meaning and is experimentally accessible (Fig. 1). These insights should greatly enhance our understanding of acute dynamic events such as cell blebbing, and perhaps even protrusions of filopodia and lamellipodia. Of course, most mechanical events in biology are substantially slower or produce no appreciable change in cellular volume, yet for such events there is no comparable level of mechanistic understanding. Still, even in this circumscribed domain of big and fast events, how poroelastic timescales might relate to the almost-universal power-law behaviour reported in experiments spanning a similar time range9 (and also predicted by the glassy worm-like chain model) remains unclear. At different scales of length and time it is likely that the cell features a diverse range of relaxation mechanisms including molecular conformation changes, protein binding and unbinding, colloidal glassy dynamics, and, as highlighted by Moeendarbary and coauthors, poroelastic cytosol flow.

Figure 1.

The cytoskeleton behaves as a poroelastic material. It can be seen as a porous elastic solid meshwork (cytoskeleton, organelles, macromolecules) bathed in an interstitial fluid (cytosol)1. Cellular rheology depends on the average filament diameter (b), the size of the particles in the cytosol (a), the hydraulic pore size (ξ) and the entanglement length of the cytoskeleton (λ).

Importantly, there is a broader context into which all these notions might be set. The cytoskeleton of the animal cell is closely comparable in its stiffness, rheology and malleability to a wide range of familiar inert mushy substances including pastes, foams, slurries and emulsions1,5,6. In fact, although differing starkly in molecular detail, these materials share elastic moduli that are small and bounded to a narrow range (102–103 Pa). Are these similarities between inert and living soft matter a coincidence, or a clue? In the laboratory it is possible to use cytoskeletal building blocks to synthesize materials whose stiffness is orders of magnitude larger or smaller than that of the living cytoskeleton. If these building blocks can attain such a wide range of stiffnesses, why is the observed range so narrow in the living animal cell? Could it be that evolutionary pressure might have constrained the earliest eukaryotes to such a peculiar mush-like adaptation?

The last common ancestor of all eukaryotes, which lived roughly 2.4 billion years ago, was a motile single-celled heterotroph that ingested particulate organic matter10 by foraging in energy-rich microbial mats that were soft and paste-like11. It has been argued that the cytoskeleton of this organism had adapted either to ingest microparticles (the phagotrophic hypothesis10) or to achieve motility11. Clearly, had the cell's cytoskeleton been much softer than that of the mat, it would have been mechanically impossible for the cell to penetrate into it. On the other hand, a cytoskeleton that is substantially stiffer would have made motility within the mat metabolically wasteful. Efficient motility, therefore, should favour the adaptation of the cell's mechanical properties to match those of the energy-rich mush-like microbial mats within which it foraged11. As a case in point, the environmental niche of the amoebozoan flagellate Phalansterium10, which may be the best surviving model of the eukaryotic last common ancestor, is the invasion of soft globular matrices (Fig. 2a).

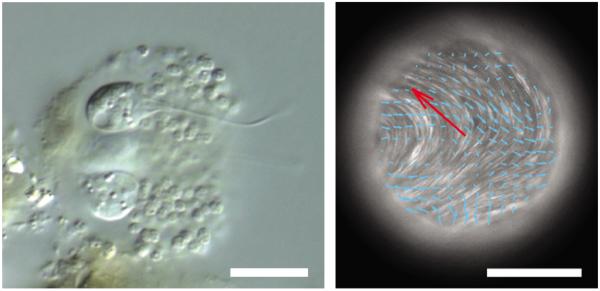

Figure 2.

The rheological properties of the cytoplasm of eukaryote cells compare to those of non-living soft matter. a, The amoebozoan flagellate Phalansterium invades soft globular matrices10. Scale bar, 10 μm. b, In the presence of ATP, microtubule bundles self-organize and adsorb at an oil/water interface, creating streaming flows (denoted by blue arrows; the red arrow indicates the direction of instantaneous droplet velocity). Scale bar, 100 μm. Figure reproduced with permission from: a, © David Patterson; b, ref. 15, © 2012 NPG.

More generally, an attractive evolutionary point of view reasons that living soft matter incorporates a limited number of ancient developmental motifs, each rooted in generic physical processes expressed by non-living soft matter12. In these motifs, biological mechanisms seem to have bootstrapped soft-matter physics, which may have served as biology's starter kit12. It has also been suggested that such mechanisms evolved so as to harness, leverage and elaborate these non-living physical effects, and then build on them a limited number of energy-dependent modules passed down to the present with few additions12. Examples are the separation of immiscible inert fluids to yield differential cell adhesion and therefore resulting in cell sorting13, the glass transition between fluid- or solid-like states to yield collective cellular migration14, and simple suspensions comprising microtubules in water, which can harness ATP to self-organize and subsequently create active organized streaming flows (Fig. 2b). All this hints to the possibility that cytoskeletal origins are mush-like. If true, then the contemporary cell might be seen as a programmable, strongly linked signalling core that is adapted to harness non-programmable, weakly linked physical interactions. It is perhaps in this way that biological entities manage to attain stability together with evolvability.

References

- 1.Bursac P, et al. Nature Mater. 2005;4:557–571. doi: 10.1038/nmat1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einstein A. Ann. Physik. 1905;19:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamenovic D. Acta Biomaterialia. 2005;1:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou EH, et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:10632–10637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901462106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabry B, et al. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:148102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.148102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trepat X, et al. Nature. 2007;447:592–595. doi: 10.1038/nature05824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl KN, Engler AJ, Pajerowski JD, Discher DE. Biophys. J. 2005;89:2855–2864. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moeendarbary E, et al. Nature Mater. 2013;12:253–261. doi: 10.1038/nmat3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolff L, Fernandez P, Kroy K. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavalier-Smith T. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002;52:297–354. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-2-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnan R, et al. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman SA. Science. 2012;338:217–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1222003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg MS. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007;17:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angelini TE, et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4714–4719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez T, Chen DT, DeCamp SJ, Heymann M, Dogic Z. Nature. 2012;491:431–434. doi: 10.1038/nature11591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]