Abstract

The progress in treatment against hepatitis B virus (HBV) with the development of effective and well tolerated nucleotide analogues (NAs) has improved the outcome of patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis and has prevented post-transplant HBV recurrence. This review summarizes updated issues related to the management of patients with HBV infection before and after liver transplantation (LT). A literature search using the PubMed/Medline databases and consensus documents was performed. Pre-transplant therapy has been initially based on lamivudine, but entecavir and tenofovir represent the currently recommended first-line NAs for the treatment of patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis. After LT, the combination of HBV immunoglobulin (HBIG) and NA is considered as the standard of care for prophylaxis against HBV recurrence. The combination of HBIG and lamivudine is related to higher rates of HBV recurrence, compared to the HBIG and entecavir or tenofovir combination. In HBIG-free prophylactic regimens, entecavir and tenofovir should be the first-line options. The choice of treatment for HBV recurrence depends on prior prophylactic therapy, but entecavir and tenofovir seem to be the most attractive options. Finally, liver grafts from hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) positive donors can be safely used in hepatitis B surface antigen negative, preferentially anti-HBc/anti-hepatitis B surface antibody positive recipients.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, Liver transplantation, Hepatitis B virus immunoglobulin, Antivirals, Lamivudine, Adefovir, Entecavir, Tenofovir, Telbivudine, Resistance

Core tip: In the present review the current knowledge on the management of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection before and after liver transplantation is updated. There is no doubt that all HBV patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be treated with potent anti-HBV agents with high genetic barrier (i.e., entecavir or tenofovir). After liver transplantation, the combination of HBV immunoglobulin (HBIG) (at least for a certain period) and entecavir or tenofovir currently appears to be the most reasonable approach, while HBIG-free antiviral prophylaxis cannot be excluded in the future, particularly in patients with low risk of recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

The development of effective, well tolerated and relatively safe oral antiviral agents [nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs)] has offered the opportunity for successful management of hepatitis B virus (HBV) related chronic liver disease. However, chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is still associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Currently, it is estimated that more than half a million people die every year due to complications of liver decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1,2]. Liver transplantation (LT) remains the only hope for many patients with complications of end-stage CHB, mostly HCC[2,3].

The introduction of passive immunoprophylaxis using long-term hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) in early 1990s significantly decreased the rates of post-LT HBV recurrence[4]. During the last 15 years, the use of NAs has decreased the need for LT due to HBV decompensated cirrhosis and has further improved the outcome of HBV transplant patients[5]. NAs have been used either in combination with HBIG or as monotherapy in an effort to further improve the rates of HBV recurrence after LT and/or reduce the need for expensive HBIG preparations[5]. The management of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive transplant patients can be divided into the pre-transplant, prophylactic post-transplant and therapeutic post-transplant approach[6]. HBV prophylaxis is also required for recipients who receive grafts from anti-hepatitis B core (HBc) positive donors, as they are at risk for de novo HBV infection.

PRE-TRANSPLANT APPROACH

Anti-HBV therapy in HBV decompensated cirrhosis

The aim of antiviral therapy is to reverse or delay complications of cirrhosis and the need for LT, and to decrease the risk of HBV re-infection in those who eventually undergo LT. Currently, there are five oral NAs that have been licensed for the treatment of CHB: three nucleoside (lamivudine, telbivudine, entecavir) and two nucleotide (adefovir dipivoxil and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) analogues[7-9]. NAs target the reverse transcriptase of HBV and achieve inhibition of HBV replication via their incorporation in viral HBV DNA causing DNA chain termination[7-9]. Antiviral therapy should be started immediately in patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis and any level of detectable serum HBV DNA regardless of ALT activity.

Lamivudine was the first NA approved for treatment of CHB and probably remains the most widely used NA worldwide due to its low cost. Its efficacy, at a daily dose of 100 mg, has been confirmed in randomized controlled trials and cohort studies showing stabilization or even improvement of liver function and reduction in the incidence of HCC[10] and the need for LT[11-13]. However, long-term lamivudine monotherapy is associated with progressively increasing rates of viral resistance due to YMDD mutations (15%-25% at year 1, 65%-80% at year 5), which can lead to clinical deterioration with development of liver failure and even death[13-15]. Importantly, patients with detectable HBV DNA at LT have increased rates of post-transplant recurrence of HBV[16,17] and even of pre-existing HCC[18]. Thus, lamivudine monotherapy is not currently recommended for patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis[7-9].

Adefovir was the second NA approved for the treatment of CHB. It is effective against both wild type and lamivudine resistant HBV strains[3]. Adefovir at the daily licensed dose of 10 mg improves liver function in patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis[19]. However, its weak potency[20], the moderate risk of resistance during long-term therapy in naive patients (29% at year 5)[21-23] and its higher cost have resulted in its replacement by the newer, more effective and cheaper nucleotide analogue, tenofovir, in all countries with tenofovir availability[9,21]. Finally, adefovir has been associated with renal adverse events including decline of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and proximal tubular dysfunction resulting occasionally in Fanconi syndrome[24,25]. The potential nephrotoxicity, which seems to be dose dependent[26], is of particular concern in difficult-to-manage patients with decompensated cirrhosis.

Telbivudine is a potent nucleoside analogue[27] which achieves satisfactory virological remission rates in CHB patients with undetectable HBV DNA at 24 wk of therapy[28]. However, it also selects for mutations in the YMDD motif, but at a lower rate compared to lamivudine [25% vs 40% after 2 years of treatment in hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive CHB patients][3,8,9]. In a recent randomized trial[29] including 232 naïve patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis, telbivudine was well tolerated. In addition, telbivudine, compared to lamivudine, achieved greater viral suppression, similar stabilization of liver function and significant improvement in the estimated GFR[29]. The place of telbivudine monotherapy in the treatment of patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis is unclear due to its unfavourable resistance profile, compared to the newer NAs with high genetic barrier [i.e., entecavir (ETV) and tenofovir (TDF)]. However, its use in a combined regimen may need further evaluation in patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis due to the potentially favourable effect of telbivudine on renal function[30].

ETV (0.5 mg daily) is a selective anti-HBV agent with potent activity against wild type HBV[7,31]. ETV has a high genetic barrier to resistance in naïve patients (< 1.5% cumulative rate of viral resistance after 6 years of treatment)[32,33] including those with advanced fibrosis or histological cirrhosis[34]. Regarding safety, lactic acidosis has been occasionally reported in small cohorts patients with severe liver dysfunction receiving ETV[35]. However, its true incidence is unclear, since studies with larger cohorts did not confirm this lethal complication[2,31]. In any case, close monitoring is advised for ETV and perhaps any NA treated patient with MELD score ≥ 20. The high efficacy and the minimal resistance rates combined with the lack of significant nephrotoxicity make ETV a first-line option for the treatment of naive patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis[36]. On the other hand, ETV monotherapy even at the licensed dosage of 1 mg daily taken ≥ 2 h away from food is not a good option for patients with lamivudine resistance, as HBV resistance develops in approximately 50% of lamivudine resistant patients after five years of ETV treatment[37,38].

TDF is the most recently approved agent for the treatment of CHB. Although it is structurally similar to adefovir, it is more potent with activity against both wild type and nucleoside-resistant HBV strains[21,39-41]. It is also active in patients with primary non-response to adefovir[2]. To date, there has been no confirmed case of drug resistance in CHB patients treated with TDF for 6 years, although most patients remaining viremic after 72 wk and being therefore at the highest risk for drug resistance received additional treatment with emtricitabine[42]. Due to its great potency and high genetic barrier, TDF has a beneficial effect on regression of advanced liver fibrosis[43]. Although TDF may be potentially nephrotoxic, similar rates of renal adverse events were observed after one year of therapy with TDF, TDF plus emtricitabine or ETV in patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis[44].

In conclusion, ETV and TDF are potent antiviral agents with a minimal or even no risk of resistance and therefore they represent the currently recommended first-line NAs for the treatment of patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis[5]. In addition, TDF is the preferred option for patients with lamivudine, ETV or telbivudine resistance, while the use of ETV (even at a higher daily dose of 1.0 mg) is a less attractive option for the long-term treatment of patients with known lamivudine resistant strains[9]. Whether a combination of antivirals could offer additional benefits is unknown. Given the current cost of anti-HBV agents, the combination that might have a reasonable cost is that of TDF plus lamivudine or emtricitabine[5]. The combination of TDF with emtricitabine was reported not to be significantly superior to TDF or ETV monotherapy[44], but the small numbers of patients in each group of this study cannot allow strong conclusions. Thus, whether any NA combination therapy would confer benefits in patients with impaired renal function who need NA dose reductions or in patients with very high baseline viral load has not been completely clarified yet. Telbivudine (alone or in a combined regimen) with its potentially favorable effect on glomerular filtration seems to be an attractive option in patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis and renal dysfunction[30].

Referral for liver transplantation

Patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis should be referred for LT, since the relevant criteria are fulfilled in most of these patients with hepatic dysfunction (Child-Pugh score ≥ 7 or MELD score ≥ 10) and/or at least one major complication (ascites, variceal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy)[45]. While waiting for LT, the patients should be monitored carefully at least every 3 mo for virologic response and possible virologic breakthrough in order to achieve serum HBV DNA undetectability using a sensitive polymerase chain reaction assay[36,46]. Interestingly, the liver function of patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis may substantially improve under effective antiviral therapy and LT candidates may be eventually withdrawn from the transplant lists[47,48] (Table 1). However, the most important parameters affecting the outcome of patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis under antiviral agents have not been completely elucidated.

Table 1.

Studies of nucleos/tide analogues in patients with hepatitis B related decompensated cirrhosis

| Ref. | Fontana et al[47] | Schiff et al[19] | Shim et al[31] | Liaw et al[44] | Chan et al[29] | Hyun et al[49] |

| Number of patients | 154 | 226 | 70 | 45/45/22 | 114/114 | 45/41 |

| NA(s) used | LAM | ADV | ETV | TDF/TDF + FTC/ETV | LdT/LAM | ETV/LAM |

| Baseline data | ||||||

| LAM resistance (%) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 18/22/14 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| CTP score | 9 | NR | 8.4 | 7/7/7 | 8.1/8.5 | 9.6/9.5 |

| MELD score | NR | NR | 11.5 | 11/13/10.5 | 14.7/15.5 | 16.7/16.1 |

| 1-yr data | ||||||

| ↓ CTP score ≥ 2 (%) | NR | NR | 49 | 26/48/42 | 32/39 | NR/NR |

| MELD score ↓ | NR | -2 | -2.2 | -2/-2/-2 | -1.0/-2.0 | -4.9/-3.7 |

| 1-yr survival (%) | 84 | 86 | 87 | 96/96/91 | 94/88 | 90.7/92.4 |

| Prognostic factors of the outcome | Serum bilirubin and creatinine levels at baseline | NR | NR | NR | NR | Baseline CTP and MELD at 3 mo |

ADV: Adefovir; CTP: Child-Turcotte-Pugh; ETV: Entecavir; TDF: Tenofovir; FTC: Emtricitabine; LAM: Lamivudine; LdT: Telbivudine; MELD: Model for end stage liver disease; NR: Not reported; NAs: Nucleostide analogues.

Previous studies using lamivudine monotherapy showed that baseline HBV DNA levels are independently associated with the outcome[47], but in a recent study using a quantitative PCR technique, neither HBV DNA at baseline nor its changes from baseline to 3 mo of treatment were associated with death or LT[49]. Most of the studies including patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis under oral antivirals have shown that the baseline severity of liver disease, expressed by the Child-Pugh score or the baseline bilirubin and creatinine levels, are critical for the outcome[47,49] (Table 1). In a prospective multicenter study[47] including 154 lamivudine treated patients with HBV decompensated cirrhosis, most of the deaths (78%) occurred within the first 6 mo suggesting that lamivudine may not be able to reduce the short-term mortality or the need for LT in patients with very advanced liver failure. In contrast, initiation of antiviral therapy at earlier stages is associated with better chances of liver function recovery, since clinical benefit may take 3-6 mo. Whether these results are still valid with the current more potent anti-HBV agents is not clear, but this might be still the case as patients with very advanced liver failure may not benefit from antiviral therapy regardless of the rapidity of the inhibition of viral replication[2]. Nevertheless, further well designed large studies with longer follow-up are needed for final conclusions (Table 1).

PROPHYLACTIC POST-TRANSPLANT APPROACH

Hepatitis B immune globulin

HBIG is a polyclonal antibody to HBsAg derived from pooled human plasma[50]. Its mechanism of action is not completely understood, but it possibly acts by binding with circulating viral particles preventing hepatocyte infection[50]. It also seems to undergo endocytosis by hepatocytes decreasing HBsAg secretion[50]. HBIG was introduced in the early nineties leading to reduction in the rates of post-transplant HBV recurrence[4]. In the landmark study by Samuel et al[4] in 1991, it was shown that HBV recurrence could be prevented in 80% of transplant patients treated with HBIG. Prior to the availability of NAs, the initial anti-HBV prophylaxis included administration of high dosage HBIG monoprophylaxis at the anhepatic phase followed by daily doses and then monthly at a fixed dose or according to anti-HBs titers (usually aiming to maintain anti-HBs titers > 100-500 IU/L)[51-53]. However, protocols that use high doses of HBIG are expensive (estimated cost at least $50000-70000 for the first year and $25-40000 for each additional year post-transplant)[54]. Additional limitations of HBIG include the unreliable supply, the parenteral administration, the local or systemic side effects and the risk of infection from HBV mutants that escaped from neutralization[50].

The use of HBIG monoprophylaxis was abandoned after the introduction of lamivudine and the more recent and potent NAs[55]. Nowadays, the most commonly used protocol includes the combination of a NA with a low dose of HBIG[5,55]. Several efforts have tried to reduce the cost using HBIG in lower dosage or preparations for intramuscular administration, which have similar pharmacokinetic properties with intravenous preparations[56], or subcutaneous HBIG[57]. Another strategy has been the substitution of HBIG with HBV vaccination. However, results on the efficacy of active vaccination using new vaccines and adjuvants are rather conflicting[58-60], and therefore, further studies with greater numbers of patients and longer follow-up periods are required before definite conclusions can be drawn.

Prophylactic post-transplant combined approach

Currently, the combination of HBIG and NA is considered the standard of care against HBV recurrence after LT[5]. This combined regimen relies on the complimentary mechanisms of action of HBIG and NA[55]. A recent meta-analysis of 6 studies showed that HBIG plus lamivudine, compared to HBIG alone, was associated with 12-fold, 12-fold and 5-fold reduction of HBV recurrence, HBV-related death and all-cause post-transplant mortality, respectively[61]. A second meta-analysis also showed that the combination of HBIG and lamivudine was superior in preventing only serum HBsAg re-appearance, compared to lamivudine alone[62]. However, lamivudine is not considered an optimal first-line option because of the progressively increasing rates of viral resistance[5,63]. This was confirmed in our systematic review[55] including 2162 HBV liver transplant recipients from 46 studies. In this review, we found that the patients under HBIG and lamivudine, compared to those under HBIG and adefovir (with or without lamivudine) had HBV recurrence more frequently (6.1% vs 2%, P = 0.024), although they had detectable HBV DNA less frequently at the time of LT (39% vs 70%, P < 0.001).

Although several questions about the ideal duration, dosage, frequency and mode of HBIG administration remain unanswered[55], we found that patients under HBIG and lamivudine who received high (≥ 10000 IU/d) dosage of HBIG, compared to those who received low HBIG dosage (< 10000 IU/d) during the 1st wk post-LT, had significantly less frequent HBV recurrences (3.3% vs 6.5%, P = 0.016). On the other hand, HBIG administration had no impact on HBV recurrence in patients under HBIG and adefovir. Based on these findings[55], we concluded that the patients under HBIG and lamivudine combination prophylaxis should receive high HBIG dosage (10000 IU IV) for the first week after LT, while the characteristics of the HBIG protocol do not seem to have any impact on the efficacy of HBIG and adefovir combination prophylaxis against HBV recurrence.

Adefovir has several drawbacks in the post-transplant setting including high cost, relatively low potency in the licensed 10 mg daily dose, risk of viral resistance and risk of nephrotoxicity[5]. The latter is of particular concern in liver transplant recipients because most of them receive nephrotoxic calcineurin inhibitors as part of an immunosuppressive regimen and frequently suffer from diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension.

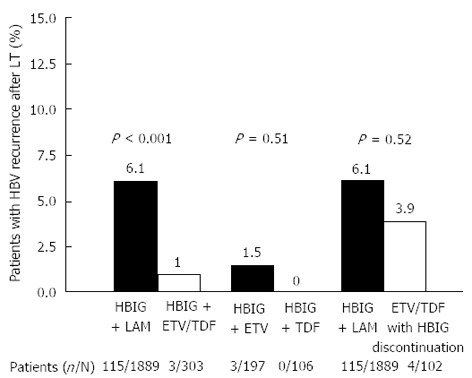

Newer and more potent NAs with a higher genetic barrier, such as ETV and TDF, are currently used in the post-transplant period in many transplant centers, mainly in an effort to increase the efficacy of post-LT prophylaxis and/or reduce the need for the expensive HBIG preparations at least after the initial post-operative period[5]. The efficacy of ETV and TDF was evaluated in our recently published systematic review including 519 HBV liver transplant recipients from 17 studies[64]. We found that patients under HBIG and lamivudine developed HBV recurrence significantly more frequently, compared to patients under HBIG and ETV or TDF combination (6.1% vs 1.0%, P < 0.001) (Figure 1), although they received a more intense HBIG protocol after LT[64]. In addition, ETV and TDF had similar antiviral efficacy when they combined with HBIG (1.5% vs 0%, respectively, P > 0.05)[64] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk of recurrence of hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation in relation to the type of post-transplant hepatitis B virus prophylaxis[64]. HBIG: Hepatitis B immunoglobulin; LAM: Lamivudine; ETV: Entecavir; TDF: Tenofovir; LT: Liver transplantation.

Given the several limitations of HBIG and the fact that waiting list patients are more likely to undergo LT with undetectable HBV DNA, one relatively recent strategy has been the use of HBIG for a limited post-transplant period followed by long-term NA therapy alone[64]. The first results published with lamivudine monoprophylaxis after HBIG withdrawal were encouraging[65,66], but longer follow-up showed that 20% of patients eventually experienced recurrence of HBV[65,67]. ETV and TDF, however, may allow early and safe discontinuation of HBIG. Strong data are not available, but our systematic review[64] showed that ETV or TDF monoprophylaxis after HBIG discontinuation does not seem to be inferior to the combination of a newer NA with HBIG or the combination of HBIG plus lamivudine (3.9% vs 1.0%, 3.9% vs 6.1%, P > 0.05) (Figure 1). Although larger studies with longer follow-up are needed for definitive conclusions, this approach has been already used in several transplant centres, particularly in patients with relatively low risk of HBV recurrence[68].

Prophylactic post-transplant monotherapy with nucleos(t)ides analogues

The high efficacy of antiviral prophylaxis using a shorter course of HBIG with continuation of NA without HBIG, and the availability of NAs without cross-resistance in cases of prophylaxis failure, led to the consideration of HBIG-free prophylactic regimens. This approach, which is challenging and controversial, started with lamivudine, but the unacceptably high rates of HBV recurrence (up to 35%-50% of cases at 2 years post-transplant)[69-74] has rendered this approach suboptimal. However, recent studies have renewed the interest in HBIG-free prophylactic regimens using the more potent regimens with high genetic barrier ETV and TDF. Recently, Fung et al[75] evaluated 80 consecutive patients transplanted for HBV-related liver disease. Fifty nine (74%) of the patients had detectable HBV DNA at the time of LT, and all patients received ETV monoprophylaxis without HBIG at any time point after LT. After a median follow-up of 26 mo, 18 (22.5%) patients were HBsAg positive, but only one of them had detectable HBV DNA[75]. In their subsequent study[76] including 362 transplant recipients under HBIG-free prophylaxis, none of the patients who receive ETV had HBV recurrence, compared to 17% of those who received lamivudine, highlighting the importance of using potent regimens with a high genetic barrier (ETV or TDF) in HBIG-free prophylaxis protocols.

In our recent systematic review[64], HBV recurrence was observed significantly more frequently in patients who received ETV or TDF HBIG-free prophylaxis, compared to patients under combination of HBIG and lamivudine prophylaxis, if the definition of HBV recurrence was based on HBsAg positivity (26% vs 5.9%, P < 0.0001). However, if the definition of HBV recurrence was based on HBV DNA detectability, the rates of HBV recurrence were similar between the two groups (0.9% vs 3.8%, P = 0.11)[64]. Given the current availability of potent NAs with negligible risk of long-term viral resistance, the clinical significance of HBsAg seropositivity in HBV transplant patients is unclear[68]. The prognosis of non-transplant CHB patients who maintain HBV DNA undetectability under NA(s) is excellent, particularly if they had not developed cirrhosis before treatment[77], but the long-term outcome of HBsAg-positive, HBV DNA negative transplant patients under NAs needs further evaluation. In a recent study[78], 5 (20%) of 25 HBV transplant patients who discontinued anti-HBV prophylaxis became HBsAg-positive, but none of them experienced any clinically relevant event and three eventually cleared HBsAg and achieved seroconversion to anti-HBs without any therapeutic intervention.

Currently, ETV and TDF should be the first-line options for HBIG-free prophylaxis. ETV may be avoided in patients with previous lamivudine resistance, who should be preferably treated with TDF. Compliance is always an issue with long-term oral antiviral therapy, particularly in prophylaxis after LT when patients feel well but remain at life-long risk of HBV recurrence[64]. Until well designed studies determine the optimal monoprophylaxis approach, the combination of HBIG (at least for a short period) and one nucleos(t)ide appears to be the most reasonable post-transplant approach. Monoprophylaxis with the new nucleos(t)sides analogues cannot be excluded in the future, particularly in patients with low risk of recurrence[68].

THERAPEUTIC POST-TRANSPLANT APPROACH

Recurrence of HBV infection after LT is usually characterized by reappearance of serum HBsAg and/or serum HBV DNA, which is frequently accompanied with biochemical or clinical evidence of recurrent liver disease. As mentioned before, particularly in patients under HBIG-free post-LT HBV prophylaxis, the definition of HBV recurrence might be reconsidered, as HBsAg seropositivity, usually in low titers, with undetectable HBV DNA, normal liver enzymes and no clinical manifestations of HBV recurrence may not have any clinical impact on the long-term graft and patient survival.

The choice of treatment for HBV recurrence depends on prior prophylactic therapy. In general, the principles of treatment in post-transplant HBV recurrence resemble those in the pre-transplant setting. ETV may be preferred in NA-naïve patients because of the lack of nephrotoxicity, although in a recent study there was no difference in renal complications between ETV and TDF in liver transplant recipients[68]. In patients with prior lamivudine resistance, TDF is the best choice[37]. Little is known about the efficacy and safety of the combination of TDF and ETV which might be used in patients with multidrug resistant HBV strains.

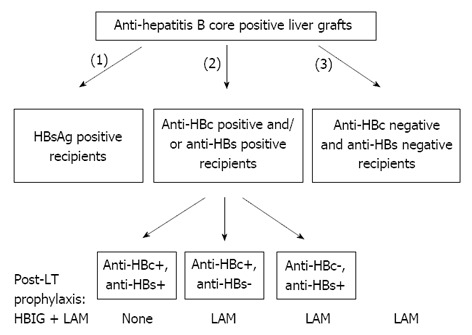

ANTI-HBC POSITIVE DONORS

The current efforts to overcome the organ shortage include the use of marginal liver grafts, such as those from anti-HBc positive donors. This source of organs can be of particular importance in countries with high prevalence of HBV infection, such as the Mediterranean area and Asia. HBsAg positive liver patients are the optimal recipients to receive liver grafts from anti-HBc positive donors. Unfortunately, the “occult” HBV infection in the donor liver may be reactivated in the HBsAg negative recipient due to post-LT immunosuppressive therapy leading to de novo HBV infection. In our systematic review[79] including 903 recipients of anti-HBc positive liver grafts, de novo HBV infection developed in 19% of HBsAg negative recipients being less frequent in anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive than HBV naive cases without prophylaxis (15% vs 48%, P < 0.001). Anti-HBV prophylaxis reduced de novo infection rates in both anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive (3%) and HBV naive recipients (12%)[79]. De novo HBV infection rates were 19%, 2.6% and 2.8% in HBsAg-negative recipients under HBIG, lamivudine and their combination, respectively. Based on these findings[79], we concluded that liver grafts from anti-HBc positive donors can be safely used in HBsAg negative recipients, preferentially in anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive recipients who may need no prophylaxis at all, while the anti-HBc and/or anti-HBs negative recipients should receive long-term prophylaxis with lamivudine (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proposed algorithm for allocation and management of anti-hepatitis B core positive liver grafts. Such grafts should be first offered to hepatitis B surface antigen positive, then to anti-hepatitis B core (HBc) and/or anti-hepatitis B surface (HBs) positive and lastly to hepatitis B virus naive (both anti-HBc and anti-HBs negative) recipients[79]. LT: Liver transplantation; HBIG: Hepatitis B immunoglobulin; LAM: Lamivudine.

CONCLUSION

Over the last two decade, the progress in anti-HBV therapy has led to great improvements in the management of HBV patients before and after LT. There is no doubt that all HBV patients with decompensated cirrhosis should be treated with a potent antiviral agent with minimal or no risk of resistance, i.e. ETV or TDF. In addition, TDF is the preferred option for patients with prior lamivudine, ETV or telbivudine resistance. An effective pre-transplant anti-HBV therapy often stabilizes or even improves the underlying liver disease resulting sometimes in withdrawals from the transplant list. In addition, achievement of serum HBV DNA undetectability prevents post-transplant HBV recurrence. After LT, the combination of HBIG (at least for a certain period) and one NA (ETV or TDF) currently appears to be the most reasonable prophylaxis, while monoprophylaxis with ETV or TDF cannot be excluded in the future, particularly in patients with low risk of recurrence. Depending on previous drug exposure and possible pre-existing resistance mutations, ETV or TDF seem to be the most attractive options for post-LT HBV recurrence as well. Finally, liver grafts from anti-HBc positive donors can be safely used in HBsAg negative, preferentially anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive recipients.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Hilmi I, Koch-Institute R, Sugawara Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Maddrey WC. Hepatitis B: an important public health issue. J Med Virol. 2000;61:362–366. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200007)61:3<362::aid-jmv14>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peng CY, Chien RN, Liaw YF. Hepatitis B virus-related decompensated liver cirrhosis: benefits of antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2012;57:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papatheodoridis GV, Manolakopoulos S, Dusheiko G, Archimandritis AJ. Therapeutic strategies in the management of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:167–178. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuel D, Muller R, Alexander G, Fassati L, Ducot B, Benhamou JP, Bismuth H. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312163292503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas E, Archimandritis AJ, Burroughs AK. Current management of hepatitis B virus infection before and after liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2009;29:1294–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papatheodoridis GV, Sevastianos V, Burroughs AK. Prevention of and treatment for hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation in the nucleoside analogues era. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:250–258. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papatheodoridis GV. Why do I treat HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients with nucleos(t)ide analogues? Liver Int. 2013;33 Suppl 1:151–156. doi: 10.1111/liv.12054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villeneuve JP, Condreay LD, Willems B, Pomier-Layrargues G, Fenyves D, Bilodeau M, Leduc R, Peltekian K, Wong F, Margulies M, et al. Lamivudine treatment for decompensated cirrhosis resulting from chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2000;31:207–210. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor D, Guptan RC, Wakil SM, Kazim SN, Kaul R, Agarwal SR, Raisuddin S, Hasnain SE, Sarin SK. Beneficial effects of lamivudine in hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:308–312. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manolakopoulos S, Karatapanis S, Elefsiniotis J, Mathou N, Vlachogiannakos J, Iliadou E, Kougioumtzan A, Economou M, Triantos C, Tzourmakliotis D, et al. Clinical course of lamivudine monotherapy in patients with decompensated cirrhosis due to HBeAg negative chronic HBV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:57–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lok AS, Lai CL, Leung N, Yao GB, Cui ZY, Schiff ER, Dienstag JL, Heathcote EJ, Little NR, Griffiths DA, et al. Long-term safety of lamivudine treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1714–1722. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papatheodoridis GV, Dimou E, Laras A, Papadimitropoulos V, Hadziyannis SJ. Course of virologic breakthroughs under long-term lamivudine in HBeAg-negative precore mutant HBV liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;36:219–226. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merle P, Trepo C. Therapeutic management of hepatitis B-related cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat. 2001;8:391–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenau J, Bahr MJ, Tillmann HL, Trautwein C, Klempnauer J, Manns MP. Lamivudine and low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin for prophylaxis of hepatitis B reinfection after liver transplantation possible role of mutations in the YMDD motif prior to transplantation as a risk factor for reinfection. J Hepatol. 2001;34:895–902. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman MA, Ghobrial RM, Tong MJ, Hiatt JR, Cameron AM, Busuttil RW. Antiviral prophylaxis and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation in patients with hepatitis B. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:3276–3280. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff E, Lai CL, Hadziyannis S, Neuhaus P, Terrault N, Colombo M, Tillmann H, Samuel D, Zeuzem S, Villeneuve JP, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for wait-listed and post-liver transplantation patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B: final long-term results. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:349–360. doi: 10.1002/lt.20981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Wulfsohn MS, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:800–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, Gane E, de Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadziyannis SJ, Papatheodoridis GV. Adefovir dipivoxil in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2004;2:475–483. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Ma J, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1743–1751. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gara N, Zhao X, Collins MT, Chong WH, Kleiner DE, Jake Liang T, Ghany MG, Hoofnagle JH. Renal tubular dysfunction during long-term adefovir or tenofovir therapy in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1317–1325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ha NB, Ha NB, Garcia RT, Trinh HN, Vu AA, Nguyen HA, Nguyen KK, Levitt BS, Nguyen MH. Renal dysfunction in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with adefovir dipivoxil. Hepatology. 2009;50:727–734. doi: 10.1002/hep.23044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izzedine H, Hulot JS, Launay-Vacher V, Marcellini P, Hadziyannis SJ, Currie G, Brosgart CL, Westland C, Arterbrun S, Deray G. Renal safety of adefovir dipivoxil in patients with chronic hepatitis B: two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1153–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, Hsu CW, Thongsawat S, Wang Y, Chen Y, Heathcote EJ, Rasenack J, Bzowej N, et al. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576–2588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liaw YF, Gane E, Leung N, Zeuzem S, Wang Y, Lai CL, Heathcote EJ, Manns M, Bzowej N, Niu J, et al. 2-Year GLOBE trial results: telbivudine Is superior to lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:486–495. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan HL, Chen YC, Gane EJ, Sarin SK, Suh DJ, Piratvisuth T, Prabhakar B, Hwang SG, Choudhuri G, Safadi R, et al. Randomized clinical trial: efficacy and safety of telbivudine and lamivudine in treatment-naïve patients with HBV-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:732–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2012.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pipili CL, Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas EC. Treatment of hepatitis B in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;84:880–885. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shim JH, Lee HC, Kim KM, Lim YS, Chung YH, Lee YS, Suh DJ. Efficacy of entecavir in treatment-naïve patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z, et al. Long-term entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and continued histological improvement in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;52:886–893. doi: 10.1002/hep.23785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J, Wilber RB, et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503–1514. doi: 10.1002/hep.22841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiff E, Simsek H, Lee WM, Chao YC, Sette H, Janssen HL, Han SH, Goodman Z, Yang J, Brett-Smith H, et al. Efficacy and safety of entecavir in patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2776–2783. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lange CM, Bojunga J, Hofmann WP, Wunder K, Mihm U, Zeuzem S, Sarrazin C. Severe lactic acidosis during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with entecavir in patients with impaired liver function. Hepatology. 2009;50:2001–2006. doi: 10.1002/hep.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tenney DJ, Pokornowski KA, Rose RE, Baldick CJ, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Yang JY, Xu D, Brett-Smith H, Spiegelmacher N, et al. Entecavir at five years shows long-term maintenance of high genetic barrier to hepatitis B virus resistance. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:P059. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini SA. Antiviral drug resistance: clinical consequences and molecular aspects. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:162–170. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132–143. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karatayli E, Idilman R, Karatayli SC, Cevik E, Yakut M, Seven G, Kabaçam G, Bozdayi AM, Yurdaydin C. Clonal analysis of the quasispecies of antiviral-resistant HBV genomes in patients with entecavir resistance during rescue treatment and successful treatment of entecavir resistance with tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:77–85. doi: 10.3851/IMP2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim YJ, Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Lee JH. Tenofovir rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients after multiple treatment failures. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6996–7002. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snow-Lampart A, Chappell B, Curtis M, Zhu Y, Myrick F, Schawalder J, Kitrinos K, Svarovskaia ES, Miller MD, Sorbel J, et al. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients monoinfected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:763–773. doi: 10.1002/hep.24078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, Afdhal N, Sievert W, Jacobson IM, Washington MK, Germanidis G, Flaherty JF, Schall RA, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013;381:468–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liaw YF, Sheen IS, Lee CM, Akarca US, Papatheodoridis GV, Suet-Hing Wong F, Chang TT, Horban A, Wang C, Kwan P, Buti M, Prieto M, Berg T, Kitrinos K, Peschell K, Mondou E, Frederick D, Rousseau F, Schiff ER. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), emtricitabine/TDF, and entecavir in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:62–72. doi: 10.1002/hep.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray KF, Carithers RL. AASLD practice guidelines: Evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1407–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fontana RJ, Hann HW, Perrillo RP, Vierling JM, Wright T, Rakela J, Anschuetz G, Davis R, Gardner SD, Brown NA. Determinants of early mortality in patients with decompensated chronic hepatitis B treated with antiviral therapy. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:719–727. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zoulim F, Radenne S, Ducerf C. Management of patients with decompensated hepatitis B virus associated [corrected] cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14 Suppl 2:S1–S7. doi: 10.1002/lt.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyun JJ, Seo YS, Yoon E, Kim TH, Kim DJ, Kang HS, Jung ES, Kim JH, An H, Kim JH, et al. Comparison of the efficacies of lamivudine versus entecavir in patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2012;32:656–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shouval D, Samuel D. Hepatitis B immune globulin to prevent hepatitis B virus graft reinfection following liver transplantation: a concise review. Hepatology. 2000;32:1189–1195. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGory RW, Ishitani MB, Oliveira WM, Stevenson WC, McCullough CS, Dickson RC, Caldwell SH, Pruett TL. Improved outcome of orthotopic liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis with aggressive passive immunization. Transplantation. 1996;61:1358–1364. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199605150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sawyer RG, McGory RW, Gaffey MJ, McCullough CC, Shephard BL, Houlgrave CW, Ryan TS, Kuhns M, McNamara A, Caldwell SH, et al. Improved clinical outcomes with liver transplantation for hepatitis B-induced chronic liver failure using passive immunization. Ann Surg. 1998;227:841–850. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199806000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terrault NA, Zhou S, Combs C, Hahn JA, Lake JR, Roberts JP, Ascher NL, Wright TL. Prophylaxis in liver transplant recipients using a fixed dosing schedule of hepatitis B immunoglobulin. Hepatology. 1996;24:1327–1333. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fox AN, Terrault NA. The option of HBIG-free prophylaxis against recurrent HBV. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cholongitas E, Goulis J, Akriviadis E, Papatheodoridis GV. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin and/or nucleos(t)ide analogues for prophylaxis against hepatitis b virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1176–1190. doi: 10.1002/lt.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hooman N, Rifai K, Hadem J, Vaske B, Philipp G, Priess A, Klempnauer J, Tillmann HL, Manns MP, Rosenau J. Antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen trough levels and half-lives do not differ after intravenous and intramuscular hepatitis B immunoglobulin administration after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:435–442. doi: 10.1002/lt.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powell JJ, Apiratpracha W, Partovi N, Erb SR, Scudamore CH, Steinbrecher UP, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, Yoshida EM. Subcutaneous administration of hepatitis B immune globulin in combination with lamivudine following orthotopic liver transplantation: effective prophylaxis against recurrence. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:524–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaib E, Coimbra BG, Galvão FH, Tatebe ER, Shinzato MS, D’Albuquerque LA, Massad E. Does anti-hepatitis B virus vaccine make any difference in long-term number of liver transplantation? Clin Transplant. 2012;26:E590–E595. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tahara H, Tanaka Y, Ishiyama K, Ide K, Shishida M, Irei T, Ushitora Y, Ohira M, Banshodani M, Tashiro H, et al. Successful hepatitis B vaccination in liver transplant recipients with donor-specific hyporesponsiveness. Transpl Int. 2009;22:805–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lo CM, Liu CL, Chan SC, Lau GK, Fan ST. Failure of hepatitis B vaccination in patients receiving lamivudine prophylaxis after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2005;43:283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Loomba R, Rowley AK, Wesley R, Smith KG, Liang TJ, Pucino F, Csako G. Hepatitis B immunoglobulin and Lamivudine improve hepatitis B-related outcomes after liver transplantation: meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Katz LH, Paul M, Guy DG, Tur-Kaspa R. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation: hepatitis B immunoglobulin, antiviral drugs, or both? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Transpl Infect Dis. 2010;12:292–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2009.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Samuel D. Management of hepatitis B in liver transplantation patients. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24 Suppl 1:55–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. High genetic barrier nucleos(t)ide analogue(s) for prophylaxis from hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:353–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buti M, Mas A, Prieto M, Casafont F, González A, Miras M, Herrero JI, Jardí R, Cruz de Castro E, García-Rey C. A randomized study comparing lamivudine monotherapy after a short course of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIg) and lamivudine with long-term lamivudine plus HBIg in the prevention of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2003;38:811–817. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naoumov NV, Lopes AR, Burra P, Caccamo L, Iemmolo RM, de Man RA, Bassendine M, O’Grady JG, Portmann BC, Anschuetz G, et al. Randomized trial of lamivudine versus hepatitis B immunoglobulin for long-term prophylaxis of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;34:888–894. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buti M, Mas A, Prieto M, Casafont F, González A, Miras M, Herrero JI, Jardi R, Esteban R. Adherence to Lamivudine after an early withdrawal of hepatitis B immune globulin plays an important role in the long-term prevention of hepatitis B virus recurrence. Transplantation. 2007;84:650–654. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000277289.23677.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cholongitas E, Vasiliadis T, Antoniadis N, Goulis I, Papanikolaou V, Akriviadis E. Hepatitis B prophylaxis post liver transplantation with newer nucleos(t)ide analogues after hepatitis B immunoglobulin discontinuation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:479–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mutimer D, Dusheiko G, Barrett C, Grellier L, Ahmed M, Anschuetz G, Burroughs A, Hubscher S, Dhillon AP, Rolles K, et al. Lamivudine without HBIg for prevention of graft reinfection by hepatitis B: long-term follow-up. Transplantation. 2000;70:809–815. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Malkan G, Cattral MS, Humar A, Al Asghar H, Greig PD, Hemming AW, Levy GA, Lilly LB. Lamivudine for hepatitis B in liver transplantation: a single-center experience. Transplantation. 2000;69:1403–1407. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200004150-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wai CT, Lim SG, Tan KC. Outcome of lamivudine resistant hepatitis B virus infection in liver transplant recipients in Singapore. Gut. 2001;48:581. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fontana RJ, Keefe EB, Han S, Wright T, Davis GL, Lilly L, et al. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B infection following liver transplantation: Experience in 112 North American patients. Hepatology. 1999;30:301A. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chan HL, Chui AK, Lau WY, Chan FK, Hui AY, Rao AR, Wong J, Lai EC, Sung JJ. Outcome of lamivudine resistant hepatitis B virus mutant post-liver transplantation on lamivudine monoprophylaxis. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:295–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zheng S, Chen Y, Liang T, Lu A, Wang W, Shen Y, Zhang M. Prevention of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation using lamivudine or lamivudine combined with hepatitis B Immunoglobulin prophylaxis. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:253–258. doi: 10.1002/lt.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fung J, Cheung C, Chan SC, Yuen MF, Chok KS, Sharr W, Dai WC, Chan AC, Cheung TT, Tsang S, et al. Entecavir monotherapy is effective in suppressing hepatitis B virus after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1212–1219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fung J, Chan SC, Cheung C, Yuen MF, Chok KS, Sharr W, Chan AC, Cheung TT, Seto WK, Fan ST, et al. Oral nucleoside/nucleotide analogs without hepatitis B immune globulin after liver transplantation for hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:942–948. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Papatheodoridis GV, Dimou E, Dimakopoulos K, Manolakopoulos S, Rapti I, Kitis G, Tzourmakliotis D, Manesis E, Hadziyannis SJ. Outcome of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B on long-term nucleos(t)ide analog therapy starting with lamivudine. Hepatology. 2005;42:121–129. doi: 10.1002/hep.20760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lenci I, Tisone G, Di Paolo D, Marcuccilli F, Tariciotti L, Ciotti M, Svicher V, Perno CF, Angelico M. Safety of complete and sustained prophylaxis withdrawal in patients liver-transplanted for HBV-related cirrhosis at low risk of HBV recurrence. J Hepatol. 2011;55:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Burroughs AK. Liver grafts from anti-hepatitis B core positive donors: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2010;52:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]