Abstract

AIM: To investigate whether a stapled technique is superior to the conventional hand-sewn technique for gastro/duodenojejunostomy during pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PpPD).

METHODS: In October 2010, we introduced a mechanical anastomotic technique of gastro- or duodenojejunostomy using staplers during PpPD. We compared clinical outcomes between 19 patients who underwent PpPD with a stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy (stapled anastomosis group) and 19 patients who underwent PpPD with a conventional hand-sewn duodenojejunostomy (hand-sewn anastomosis group).

RESULTS: The time required for reconstruction was significantly shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (186.0 ± 29.4 min vs 219.7 ± 50.0 min, P = 0.02). In addition, intraoperative blood loss was significantly less (391.0 ± 212.0 mL vs 647.1 ± 482.1 mL, P = 0.03) and the time to oral intake was significantly shorter (5.4 ± 1.7 d vs 11.3 ± 7.9 d, P = 0.002) in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group. There were no differences in the incidences of delayed gastric emptying and other postoperative complications between the groups.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy shortens reconstruction time during PpPD without affecting the incidence of delayed gastric emptying.

Keywords: Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, Stapled anastomosis, Gastrojejunostomy, Duodenojejunostomy, Delayed gastric emptying

Core tip: The operative procedure of pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PpPD) includes reconstruction of the pancreatic, biliary, and digestive systems, thus requiring a significant amount of time. We compared clinical outcomes between 19 patients who underwent PpPD with a stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy and 19 patients who underwent PpPD with a conventional hand-sewn duodenojejunostomy. We demonstrate that stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy shortens reconstruction time during PpPD without affecting the incidence of delayed gastric emptying.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) remains one of the major and challenging operations associated with a relatively high mortality and morbidity rate. The PD operative procedure includes reconstruction of the pancreatic, biliary, and digestive systems, thus requiring a significant amount of time. Because prolonged operative time has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for mortality and postoperative complications[1-3], efforts should be made to shorten the operative time by improving surgical skills and techniques.

The introduction of mechanical suture/stapling devices has provided surgeons with options for simple and sophisticated reconstruction methods in the field of gastrointestinal surgery. Recently, anastomotic techniques using staplers have been increasingly used for operations of the esophagus, stomach, and colorectum, particularly since the advent of laparoscopic surgery. In general, stapled anastomoses require less operative time and provide equal or better results in terms of the rate of leakage compared with hand-sewn anastomoses[4].

Although stapled anastomoses can be used for reconstruction of the alimentary tract in virtually all operations, only a few studies have described such a method in the setting of pancreatic resection[5,6]. We introduced a mechanical anastomotic technique of gastro- or duodenojejunostomy using staplers during pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PpPD). In an attempt to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy, we compared the outcomes between the stapled and conventional hand-sewn anastomotic techniques in patients undergoing PpPD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The study included 38 patients (25 men and 13 women with a mean age of 66 years) who underwent PpPD for cancers of the pancreatic head, ampulla of vater, lower bile duct, and gallbladder; cystic neoplasms of the pancreas; neuroendocrine tumors; and others (chronic pancreatitis and duodenal submucosal tumor) at our institution between January 2009 and March 2012. Patients who underwent classical pancreaticoduodenectomy (whipple operation), subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (SSPPD), and laparoscopy-assisted pancreaticoduodenectomy were excluded from this study. In October 2010, we altered the technique of alimentary tract reconstruction (gastro/duodenojejunostomy and Braun anastomosis) from the conventional hand-sewn technique to a mechanical anastomosis technique using staplers. The patients were divided into two groups according to the method of alimentary tract reconstruction: 19 patients who underwent hand-sewn duodenojejunostomy (hand-sewn anastomosis group) and 19 patients who underwent stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy (stapled anastomosis group).

Operative procedure

The detailed PpPD operative procedure was previously described elsewhere[7]. We routinely use the modified Child method for reconstruction. After removal of the pancreatic head, the anal stump of the jejunum was lifted through the mesocolon right to the middle colic artery. The pancreaticojejunostomy was performed using a modified Kakita’s method[8]. A mucosa-to-mucosa anastomosis of the pancreaticojejunostomy was performed with interrupted sutures using 5-0 monofilament absorbable sutures (PDS, Ethicon Inc., Tokyo, Japan). A pancreatic tube was placed from the jejunum to the main pancreatic duct. The hepaticojejunostomy was performed by interrupted sutures using 4-0 monofilament absorbable sutures (PDS II, Ethicon Inc.), and the biliary tube was placed from the jejunal lumen to the hepatic duct of the liver. The biliary and pancreatic tubes were taken from the jejunal stump to the outside of the body.

The conventional hand-sewn duodenojejunostomy (end-to-side anastomosis) was performed by a two-layer Albert-Lembert method (whole layer, running sutures of 4-0 PDS, and seromuscular layer, interrupted sutures of 4-0 silk). A Braun anastomosis (side-to-side jejunojejunostomy) was also performed using the same method.

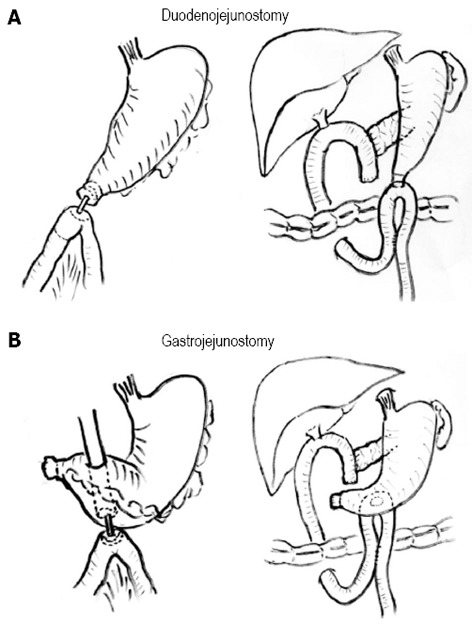

The stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy was performed using a circular stapler (CDH25, Ethicon Inc.). For duodenojejunostomy, the anvil was inserted into the stomach through a small gastrotomy incision, moved to the duodenum, and fixed at the duodenal stump by a purse-string suture. A circular stapler was inserted into the jejunal loop through a small opening and connected to the anvil to complete the anastomosis (Figure 1A). For gastrojejunostomy, the anvil was inserted into and fixed at the jejunum. A circular stapler was inserted into the stomach through a small opening made in the anterior wall of the antrum and connected to the anvil to complete the anastomosis at the posterior wall of the stomach (Figure 1B). The openings made in the stomach or jejunum were closed by either running or interrupted sutures. A Braun anastomosis (side-to-side jejunojejunostomy) was also performed mechanically using a linear stapler (GIA, Covidien Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The gastro/duodenojejunostomy was made via an antecolic route in both the hand-sewn and stapled techniques.

Figure 1.

Schema of stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy. A: Stapled duodenojejunostomy. The anvil was inserted into the stomach through a small gastrotomy incision, moved to the duodenum, and fixed at the duodenal stump by a purse-string suture. A circular stapler was inserted into the jejunal loop through a small opening and connected to the anvil for completion of anastomosis; B: Stapled gastrojejunostomy. The anvil was inserted into and fixed at the jejunum. A circular stapler was inserted into the stomach through a small opening made in the anterior wall of the antrum and connected to the anvil for completion of anastomosis at the posterior wall of the stomach.

Drainage tubes were placed at the posterior aspect of the hepaticojejunostomy and the anterior side of the pancreaticojejunostomy. They were drained to the outside of the abdomen. Biliary and pancreatic tubes were placed from the stump of the jejunum using Witzel’s method. All procedures were performed by one of the authors (Yamaguchi K).

Postoperative management

The nasogastric tube was removed when the amount of drainage fluid was less than 200 mL/d and the nature of the fluid was not bloody. Liquid oral intake was resumed after gas passage if there was no evidence of pancreatic fistula. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) was defined based on the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery classification[9]. Grade B (unable to tolerate solid oral intake by POD 14 with/without vomiting) or C (unable to tolerate solid oral intake by POD 21 with/without vomiting) was considered clinically relevant. Requirement of nasogastric tube reinsertion after POD 7 was also considered DGE.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 10 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact probability test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics in the stapled anastomosis group and hand-sewn anastomosis group

The patient characteristics in the stapled anastomosis group and the hand-sewn group are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, comorbidities, history of diabetes mellitus, previous history of upper abdominal surgery, preoperative level of serum albumin (as a nutritional status), or disease distribution between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics in the stapled anastomosis group and hand-sewn anastomosis group

| Stapled anastomosis group | Hand-sewn anastomosis group | P value | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 67.2 ± 11.7 | 65.2 ± 11.2 | 0.59 |

| Gender (M/F) | 11/8 | 14/5 | 0.50 |

| ASA | |||

| 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 10 | 16 | |

| 3 | 5 | 2 | 0.11 |

| Comorbidities n (%) | 8 (42) | 8 (42) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes n (%) | 5 (26) | 6 (32) | 1.00 |

| Previous history of upper abdominal surgery | 2 (11) | 2 (11) | 1.00 |

| Preoperative albumin level (g/dL, mean ± SD) | 3.96 ± 0.35 | 3.74 ± 0.44 | 0.10 |

| Disease | |||

| Pancreatic cancer | 6 | 4 | 0.08 |

| Ampullary cancer | 3 | 6 | |

| Lower bile duct cancer | 2 | 2 | |

| Gallbladder cancer | 1 | 0 | |

| IPMN | 3 | 3 | |

| SCN | 0 | 1 | |

| PNET | 3 | 0 | |

| Duodenal GIST | 0 | 1 | |

| Mass-forming pancreatitis | 0 | 1 | |

| Others | 1 | 1 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; IPMN: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms; SCN: Solid cystic neoplasms; PNET: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor; GIST: Gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Operative variables and postoperative outcomes in the stapled anastomosis and hand-sewn anastomosis groups

The operative variables were compared between the groups (Table 2). The mean operative time tended to be shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn group (500 min vs 530 min), although the difference was not statistically significant. However, the time required for reconstruction (removal of the pancreatic head to completion of surgery) was significantly shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (186.0 ± 29.4 min vs 219.7 ± 50.0 min, P = 0.02). The total amount of blood loss during surgery was significantly less in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn group (391.0 ± 212.0 mL vs 647.1 ± 482.1 mL, P = 0.03).

Table 2.

Operative and postoperative outcomes in the stapled anastomosis group and hand-sewn anastomosis group

| Stapled anastomosis group | Hand-sewn anastomosis group | P value | |

| Total operative time (min) | 500 ± 68.3 | 530 ± 88 | 0.33 |

| Reconstruction time (min) | 186 ± 29.4 | 219.7 ± 50 | 0.02 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 391 ± 212.3 | 647.1 ± 482.1 | 0.03 |

| Duration of nasogastric tube insertion (d) | 1.42 ± 1.22 | 1.3 ± 0.58 | 0.67 |

| Resuming liquid oral intake (POD) | 5.4 ± 1.7 | 11.3 ± 7.89 | 0.002 |

| Starting solid diet (POD) | 13.8 ± 8.56 | 17.7 ± 11.2 | 0.26 |

| Postoperative complications | 6 (31.6) | 12 (63.2) | 0.10 |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) | 0.60 |

| Pancreatic anastomotic leakage/pancreatic fistula | 1 (5.3) | 3 (15.8) | 0.60 |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 1 (5.3) | 4 (21.1) | 0.34 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 35.8 ± 12 | 39.4 ± 15.4 | 0.67 |

Values shown are mean ± SD or n (%).

We next compared the postoperative outcomes between the groups (Table 2). Although there was no difference in the duration of nasogastric tube insertion between the groups, the time from surgery to resuming liquid oral intake was significantly shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (5.4 ± 1.7 d vs 11.3 ± 7.9 d, P = 0.002). Overall, postoperative complications occurred in 18 patients, including 6 patients (31.6%) in the stapled anastomosis group and 12 patients (63.2%) in the hand-sewn group (not significant). Among the complications, pancreatic fistula/anastomotic leakage occurred in 1 patient (5.3%) in the stapled anastomosis group and in 3 patients (15.8%) in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (not significant). Intra-abdominal abscess was observed in 1 patient (5.3%) in the stapled anastomosis group and in 4 patients (21.1%) in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (not significant). No patient in either group developed leakage of the gastro/duodenojejunostomy. DGE was observed in 1 patient (5.3%; grade C) in the stapled anastomosis group and in 3 patients (15.8%; grade B in 1 patient and grade C in 2 patients) in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (not significant). There was no difference in the duration of postoperative hospital stay between the groups. No 30-d postoperative mortality was observed in either group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared clinical outcomes between the stapled and conventional hand-sewn alimentary tract anastomotic techniques in a total of 38 patients undergoing PpPD. The major findings obtained were as follows: (1) the reconstruction time was significantly shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group; (2) intraoperative blood loss was significantly less and the time from the operation to resuming oral intake was significantly shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group; and (3) there were no differences in the incidences of delayed gastric emptying and other postoperative complications between the groups. These findings suggest that stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy shortens reconstruction time during PpPD without affecting the incidence of delayed gastric emptying.

Despite the disseminated use of mechanical suture/stapling devices in the field of gastrointestinal surgery, the application of these devices to reconstruction in PD remains uncommon. To date, only one Japanese group has described the method of gastro/duodenojejunostomy using staplers during PD[5,6]. In their method of stapled reconstruction, an antecolic gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy was performed by Roux-en-Y reconstruction using a linear or circular stapler[5], which is slightly different from our technique in terms of dividing the jejunum for Roux-en-Y loop in their technique. The authors also demonstrated that the incidence of delayed gastric emptying was significantly lower in patients who underwent stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy than in those who underwent hand-sewn reconstruction[6]. In the present study, we also found that the time to resuming oral intake was significantly shorter in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group. Although the exact mechanism for improved oral intake and DGE by mechanical anastomosis is unknown, one possible explanation is that edema around the anastomotic site can be prevented by stapled anastomosis, particularly in the early postoperative period.

It has been reported that prolonged operative time is associated with an increased incidence of postoperative mortality and morbidity after PD[1-3]. According to a recent study in a total of 4817 patients undergoing PD[1], longer operative time was linearly associated with increased 30-d morbidity (P < 0.001) and mortality (P < 0.01). Therefore, it is important for surgeons to avoid prolonged operative time by improving surgical techniques. With an aim to shorten the operative time, we introduced a technique of stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy and Braun anastomosis. Although the difference in total operative time did not reach statistical significance, the reconstruction time was significantly shorter (by approximately 30 min) in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn group. Importantly, intraoperative blood loss was significantly less in the stapled anastomosis group than in the hand-sewn anastomosis group (a mean volume of 391 mL vs 647 mL). Because a variety of factors can affect the volume of intraoperative blood loss, this difference is unlikely to be attributable solely to the different reconstruction techniques used. Furthermore, because of the small number of patients in each group, the mean volume of blood loss can be affected by a small number of patients with an unexpectedly large intraoperative blood loss. However, the reduced reconstruction time observed using rapid stapling devices may have played a role, at least in part, in the reduced blood loss observed during surgery.

One concern that might be raised against our technique of stapled gastrojejunostomy is the significance of preserving the pylorus because food may not pass the pylorus in this anastomosis. By analyzing the plasma motilin concentration and phase III activity of the migrating motor complex of the stomach, it has been shown that preservation of the duodenum is important to maintain gastric motility and to prevent so-called “gastroparesis”[10,11]. In contrast to these findings, several lines of evidence have suggested that PD with pylorus resection (SSPPD) is comparable or even superior to that with pylorus preservation (PpPD) in terms of dietary intake and DGE[12-15]. Therefore, the clinical relevance of pylorus preservation requires further investigation.

Our study had several limitations. First, this study was a retrospective and historical cohort analysis; therefore, the possibility of bias cannot be eliminated. Second, the small number of patients in each anastomosis group may have underpowered our statistical evaluation. Third, we were unable to perform a cost comparison between the groups because of a lack of information. Therefore, to precisely determine the exact benefits of stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy during PpPD, a prospective randomized trial, including an analysis of cost effectiveness, should be performed in the future.

In conclusion, our preliminary results suggest that stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy is a feasible technique that could shorten the reconstruction and operative time during PpPD without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications including delayed gastric emptying. More recently, a mechanical anastomosis technique using a circular stapler has been applied to the hepaticojejunostomy during PD in selected patients with a dilated bile duct[16]. Thus, the introduction and standardization of these stapled anastomosis techniques can shorten the reconstruction time during PD and ultimately reduce the incidence of postoperative mortality and morbidity.

COMMENTS

Background

The operative procedure of pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PpPD) includes reconstruction of the pancreatic, biliary, and digestive systems, thus requiring a significant amount of time.

Research frontiers

Although stapled anastomosis can be applied to the reconstruction of alimentary tract in virtually all operations, only a few studies have described the reconstruction method of alimentary tract using staplers in the setting of pancreatic resection.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors compared clinical outcomes between 19 patients who underwent PpPD with a stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy and 19 patients who underwent PpPD with a conventional hand-sewn duodenojejunostomy.

Applications

This study showed that stapled gastro/duodenojejunostomy shortens reconstruction time during PpPD without affecting the incidence of delayed gastric emptying.

Peer review

This is a very novel report about the pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers: Ohashi M, Liu XB, Narula Vimal K S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Ball CG, Pitt HA, Kilbane ME, Dixon E, Sutherland FR, Lillemoe KD. Peri-operative blood transfusion and operative time are quality indicators for pancreatoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billingsley KG, Hur K, Henderson WG, Daley J, Khuri SF, Bell RH. Outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary cancer: an analysis from the Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:484–491. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(03)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pecorelli N, Balzano G, Capretti G, Zerbi A, Di Carlo V, Braga M. Effect of surgeon volume on outcome following pancreaticoduodenectomy in a high-volume hospital. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:518–523. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korolija D. The current evidence on stapled versus hand-sewn anastomoses in the digestive tract. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008;17:151–154. doi: 10.1080/13645700802103423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakamoto Y, Kajiwara T, Esaki M, Shimada K, Nara S, Kosuge T. Roux-en-Y reconstruction using staplers during pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective preliminary study. Surg Today. 2009;39:32–37. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3814-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakamoto Y, Yamamoto Y, Hata S, Nara S, Esaki M, Sano T, Shimada K, Kosuge T. Analysis of risk factors for delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after 387 pancreaticoduodenectomies with usage of 70 stapled reconstructions. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1789–1797. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi K. Pancreatoduodenectomy for bile duct and ampullary cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:210–215. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0480-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakita A, Yoshida M, Takahashi T. History of pancreaticojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy: development of a more reliable anastomosis technique. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2001;8:230–237. doi: 10.1007/s005340170022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, et al. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naritomi G, Tanaka M, Matsunaga H, Yokohata K, Ogawa Y, Chijiiwa K, Yamaguchi K. Pancreatic head resection with and without preservation of the duodenum: different postoperative gastric motility. Surgery. 1996;120:831–837. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka M. Gastroparesis after a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Today. 2005;35:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2961-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashibe A, Kameyama M, Shinbo M, Makimoto S. The surgical procedure and clinical results of subtotal stomach preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (SSPPD) in comparison with pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:106–109. doi: 10.1002/jso.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akizuki E, Kimura Y, Nobuoka T, Imamura M, Nishidate T, Mizuguchi T, Furuhata T, Hirata K. Prospective nonrandomized comparison between pylorus-preserving and subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy from the perspectives of DGE occurrence and postoperative digestive functions. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1185–1192. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0513-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurahara H, Takao S, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, Maemura K, Sakoda M, Ueno S, Natsugoe S. Subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (SSPPD) prevents postoperative delayed gastric emptying. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:615–619. doi: 10.1002/jso.21687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai M, Tani M, Hirono S, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, Uchiyama K, Yamaue H. Pylorus ring resection reduces delayed gastric emptying in patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of pylorus-resecting versus pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;253:495–501. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d98f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tersigni R, Capaldi M, Cortese A. Biliodigestive anastomosis with circular mechanical device after pancreatoduodenectomy: our experience. Updates Surg. 2011;63:253–257. doi: 10.1007/s13304-011-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]