Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the effect of gastrectomy on diabetes control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and early gastric cancer.

METHODS: Data from 64 patients with early gastric cancer and type 2 diabetes mellitus were prospectively collected. All patients underwent curative gastrectomy (36 subtotal gastrectomy with gastroduodenostomy, 16 subtotal gastrectomy with gastrojejunostomy, 12 total gastrectomy) and their physical and laboratory data were evaluated before and 3, 6 and 12 mo after surgery.

RESULTS: Fasting blood glucose (FBS), HbA1c, insulin, C-peptide, and homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance were significantly improved 3 mo after surgery, regardless of operation type, and the significant improvement in all measured values, except HbA1c, was sustained up to 12 mo postoperatively. Approximately 3.1% of patients stopped diabetes medication and had HbA1c < 6.0% and FBS < 126 mg/dL. 54.7% of patients decreased their medication, and had reduced FBS or HbA1c. In multivariate analysis, good diabetic control was not associated with operation type, but was associated with diabetes duration.

CONCLUSION: Diabetes improved in more than 50% of patients during the first year after gastric cancer surgery. The degree of diabetes control was related to diabetes duration.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Gastrectomy, Gastric cancer, Short-term outcome, Glucose control

Core tip: Diabetes mellitus is one of the most important health problems and has an impact on the quality of life of gastric cancer patients as well as ordinary individuals. In this study, we evaluated the impact of conventional gastric cancer surgery on type 2 diabetes. Gastric cancer surgery led to a significant improvement in type 2 diabetes during the first year after surgery, and the degree of diabetes control was related to diabetes duration.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is a leading cause of cancer death worldwide and is one of the most common cancers in Korea[1,2]. During the last several decades, there has been notable progress in the field of gastric cancer diagnosis and treatment, as indicated by the increasing proportion of early gastric cancers and improved survival rate[3,4]. Therefore, postoperative quality of life as well as the appropriate surgical treatment for a cure has become very important.

However, the increase in older patients due to an aging population and the increased incidence of lifestyle-related diseases including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and hypercholesterolemia make postoperative healthcare more difficult and complicated. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most difficult health problems worldwide as it is a multi-factorial chronic disease. In Korea, the prevalence of diabetes has increased dramatically from less than 1.5% in the 1970s to approximately 10% in the 2000s, and it is currently the 5th most common cause of death[5,6]. Although the prevalence of diabetes in gastric cancer patients has not been reported, it may be similar to that of the general population. After gastric cancer surgery, many surgeons focus on improving the nutritional status of patients rather than controlling diabetes as the main problem after gastric cancer surgery is weight loss. In addition, the beneficial effects of weight loss often lead to improvement in hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension.

Recently, metabolic surgery has become an appealing treatment option for patients with type 2 DM. The effects of metabolic surgery and the mechanism of action have been reported in several studies[7-9]. Although the purpose of metabolic surgery and gastric cancer surgery is completely different, there is a connection between the two procedures clinically and technically. In line with this thinking, the organized evaluation of the impact of conventional gastric cancer surgery on diabetes appears to be necessary. Such an evaluation will allow surgeons to select a favorable reconstruction type after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with diabetes. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the short-term effect of three types of routine gastric cancer surgery on type 2 DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We analyzed the data from 64 early gastric cancer patients with type 2 DM who underwent curative gastrectomy for primary gastric cancer between 2009 and 2010. All of the patients had been diagnosed with type 2 DM after 40 years of age and were taking medication before the diagnosis of early gastric cancer. All the data were collected prospectively. Patients with the following conditions were excluded: (1) other malignancies; (2) pre- and post-operative chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy; (3) other endocrine disorders such as thyroid or adrenal disease; (4) moderate to severe cardiovascular, pulmonary or renal disease; and (5) active infection. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital, Yonsei University College of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to surgery.

Surgical procedures

Subtotal or total gastrectomy was performed according to the tumor location. Billroth I or II reconstruction was carried out after subtotal gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy after total gastrectomy. In Billroth I reconstruction, the duodenum was transected 1 cm distal to the pyloric ring and gastroduodenostomy was performed using a circular stapler. In Billroth II reconstruction, the length from the ligament of Treitz was approximately 20 cm and gastrojejunostomy was performed using a linear stapler. After total gastrectomy, the length of the esophagojejunostomy to jejunojejunostomy was approximately 45 cm, and the length of the ligament of Treitz to jejunojejunostomy was 20-25 cm. Esophagojejunostomy was performed using a circular stapler. Generally, D1+β or D2 lymph node dissection was performed according to the guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association[10].

Evaluation of clinical variables and biochemical data during follow-up

All of the clinical and laboratory data were collected and recorded prospectively at each point of the routine follow-up. Blood samples were obtained after an overnight fast. Patients visited the hospital at 3-, 6- and 12-mo time points during the first year after gastrectomy for a physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging, and/or endoscopy. The variables for evaluating the status of glucose control included body weight, body mass index, biochemical data [serum glucose, HbA1c, insulin, C-peptide, homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, triglyceride], and medication status, and were recorded preoperatively and 3, 6 and 12 mo after surgery. All of the patients completed the study.

The degree of diabetes control was divided into three groups: (1) Remission: No medication and FBS < 126 mg/dL and HbA1c < 6.0%; (2) Improved: Reduced medication and one of the following: FBS or HbA1c reduction; and (3) Stationary: No change of medication, or patients excluded from the improved and remission categories.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS® version 15.0 for Windows® (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact test, and continuous data were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare biochemical data among the three surgical groups at the same evaluation time. The paired t test was used to compare preoperative and postoperative 12-mo biochemical data. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify the independent variables associated with the degree of diabetic control. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient demographics

The preoperative patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 24.7 ± 3.4 kg/m2. After subtotal gastrectomy, gastroduodenostomy (STG BI) was performed in 36 patients and gastrojejunostomy (STG BII) in 16 patients. Twelve patients underwent total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy (TG). Of the patients in this study, 18.8% had a family history of diabetes in first degree relatives, 93.7% were taking oral hyperglycemic agents, and 6.3% were taking insulin with or without oral agents.

Table 1.

Patient demographics n (%)

| Variables | n = 64 |

| Age (yr) | 62.7 ± 8.6 |

| Range | 45-77 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 43 (67.2) |

| Female | 21 (32.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.7 ± 3.4 |

| Range | 18.6-38.1 |

| Smoking history | |

| No | 36 (56.2) |

| Yes | 28 (43.8) |

| Alcohol history | |

| No | 38 (59.4) |

| Yes | 26 (40.6) |

| Family history of DM | |

| No | 52 (81.2) |

| Yes | 12 (18.8) |

| Operation type | |

| STG BI | 36 (56.2) |

| STG BII | 16 (25.0) |

| TG | 12 (18.8) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Open surgery | 28 (43.7) |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 36 (56.3) |

| Duration of DM (yr) | 6.6 ± 6.4 |

| Range | 0.5-25 |

| DM medication | |

| Oral hyperglycemic agents | 60 (93.7) |

| Insulin only | 1 (1.6) |

| Both | 3 (4.7) |

Data are expressed as absolute numbers (percentage) or mean ± SD. DM: Diabetes mellitus; STG BI: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis; STG BII: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis; TG: Total gastrectomy.

Changes in biochemical data after surgery

All of the patients completed 12-mo follow-up. BMI, FBS, HbA1c, insulin, C-peptide, HOMA-IR, triglyceride, LDL-cholesterol, and HDL-cholesterol were determined preoperatively and 3, 6 and 12 mo after surgery (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in biochemical data after surgery according to the follow up period and operation type

| Operation type | Preoperative | PO 3 mo | PO 6 mo | PO 12 mo | 1P pre-12 mo | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | STG BI | 24.3 ± 2.9 | 22.5 ± 2.6 | 22.3 ± 2.8 | 21.9 ± 2.7 | < 0.001 |

| STG BII | 24.7 ± 3.1 | 22.6 ± 2.9 | 22.9 ± 2.1 | 22.1 ± 1.9 | 0.002 | |

| TG | 25.7 ± 5.2 | 23.8 ± 5.7 | 22.5 ± 4.6 | 22.9 ± 4.4 | 0.004 | |

| 2P | 0.793 | 0.965 | 0.616 | 0.780 | ||

| BMI | STG BI | 100% | 92.9% ± 5.2% | 92.2% ± 5.3% | 92.0% ± 7.0% | < 0.001 |

| STG BII | 100% | 91.6% ± 6.7% | 93.3% ± 6.9% | 90.3% ± 11.0% | 0.004 | |

| TG | 100% | 90.9% ± 6.4% | 87.8% ± 5.7% | 87.1% ± 8.1% | 0.003 | |

| 2P | 1.000 | 0.661 | 0.050 | 0.333 | ||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | STG BI | 147.3 ± 44.1 | 125.0 ± 30.3 | 122.3 ± 38.4 | 114.4 ± 21.7 | 0.001 |

| STG BII | 155.7 ± 40.0 | 136.4 ± 56.6 | 122.5 ± 31.9 | 126.4 ± 39.1 | 0.061 | |

| TG | 145.9 ± 37.5 | 114.3 ± 22.2 | 117.0 ± 28.0 | 115.4 ± 27.3 | 0.234 | |

| 2P | 0.682 | 0.489 | 0.931 | 0.773 | ||

| HbA1c | STG BI | 7.2% ± 1.1% | 6.8% ± 0.6% | 7.0% ± 0.7% | 7.1% ± 0.9% | 0.834 |

| STG BII | 7.3% ± 1.3% | 6.9% ± 1.4% | 7.1% ± 1.3% | 7.1% ± 1.6% | 0.626 | |

| TG | 7.1% ± 0.8% | 6.5% ± 0.7% | 6.5% ± 0.5% | 6.5% ± 0.6% | 0.119 | |

| 2P | 0.981 | 0.227 | 0.201 | 0.201 | ||

| Insulin (μIU/mL) | STG BI | 21.3 ± 20.7 | 8.6 ± 11.2 | 8.1 ± 11.3 | 5.1 ± 4.7 | < 0.001 |

| STG BII | 22.5 ± 29.0 | 9.6 ± 8.8 | 8.9 ± 3.5 | 7.7 ± 7.1 | 0.041 | |

| TG | 18.1 ± 10.1 | 7.5 ± 5.7 | 4.0 ± 2.1 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 0.02 | |

| 2P | 0.679 | 0.652 | 0.050 | 0.350 | ||

| C-peptide (ng/mL) | STG BI | 3.4 ± 2.3 | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| STG BII | 3.3 ± 1.8 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 0.028 | |

| TG | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 0.02 | |

| 2P | 0.877 | 0.778 | 0.597 | 0.523 | ||

| HOMA-IR | STG BI | 8.7 ± 10.1 | 2.9 ± 4.7 | 2.6 ± 7.9 | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 0.001 |

| STG BII | 9.3 ± 13.5 | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 2.9 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 2.5 | 0.045 | |

| TG | 7.1 ± 4.1 | 2.1 ± 1.6 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.015 | |

| 2P | 0.660 | 0.484 | 0.036 | 0.176 | ||

| TG (mg/dL) | STG BI | 126.1 ± 80.8 | 100.1 ± 51.6 | 115.9 ± 62.6 | 101.4 ± 41.7 | 0.341 |

| STG BII | 144.8 ± 102.6 | 118.5 ± 75.9 | 124.3 ± 53.7 | 105.2 ± 44.6 | 0.114 | |

| TG | 143.5 ± 88.9 | 130.5 ± 71.4 | 72.3 ± 36.6 | 96.6 ± 37.3 | 0.082 | |

| 2P | 0.831 | 0.503 | 0.130 | 0.937 | ||

| LDL (mg/dL) | STG BI | 96.8 ± 34.7 | 89.0 ± 27.9 | 81.3 ± 23.5 | 90.8 ± 29.2 | 0.522 |

| STG BII | 97.4 ± 28.7 | 97.9 ± 33.5 | 94.4 ± 29.7 | 101.6 ± 37.5 | 0.515 | |

| TG | 113.6 ± 28.9 | 99.8 ± 28.0 | 63.5 ± 32.0 | 98.5 ± 32.0 | 0.023 | |

| 2P | 0.299 | 0.556 | 0.192 | 0.594 | ||

| HDL (mg/dL) | STG BI | 43.9 ± 10.6 | 48.3 ± 11.4 | 49.4 ± 15.1 | 52.0 ± 15.1 | 0.002 |

| STG BII | 43.2 ± 9.2 | 42.6 ± 8.2 | 46.2 ± 10.6 | 46.5 ± 8.6 | 0.173 | |

| TG | 42.4 ± 10.5 | 45.0 ± 7.3 | 48.7 ± 3.2 | 46.3 ± 8.1 | 0.073 | |

| 2P | 0.953 | 0.161 | 0.757 | 0.552 |

1Paired t-test, mean ± SD;

Kruskal-Wallis test was used to evaluate the difference by operation type at the same follow up period. Significant values are indicated in bold face. BMI: Body mass index, BMI (%) refers to percentage of BMI at each follow-up compared to preoperative BMI. STG BI: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis; STG BII: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis; TG: Total gastrectomy; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein.

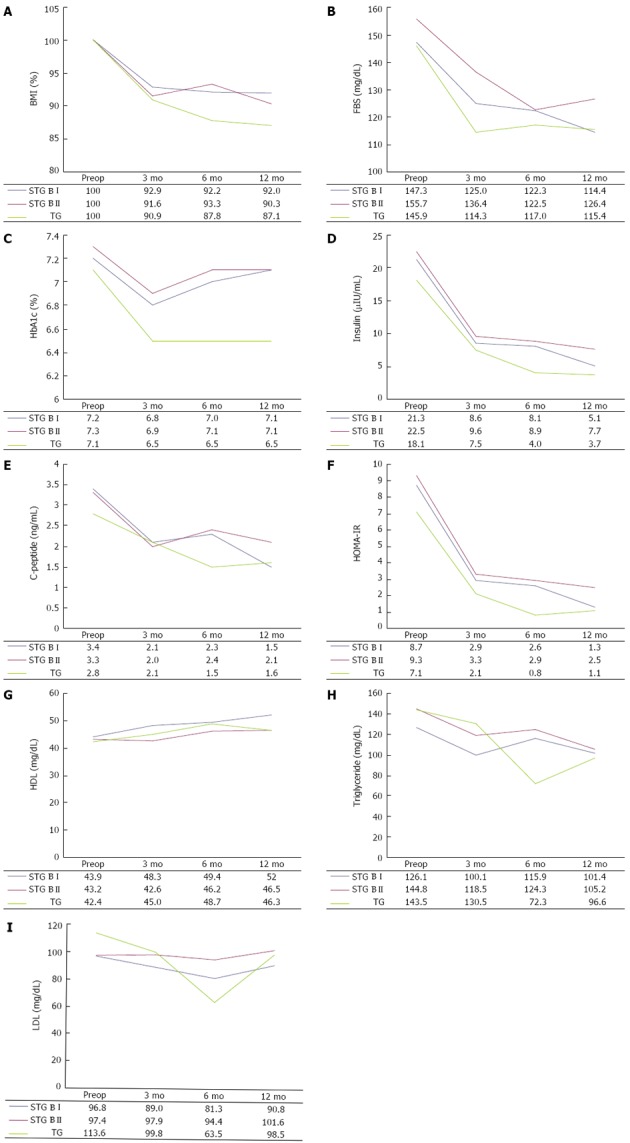

In the same operation type, data on preoperative day and postoperative 12 mo were compared. In addition, at the same follow-up points, variables of each operation type were compared. Figure 1 shows the changes in mean value of the biochemical data. BMI rapidly decreased during the first 3 mo after surgery and was maintained up to 12 mo (Figure 1A). In all operation types, the 12-mo postoperative BMI value significantly decreased to approximately 90% of the preoperative value. At the same follow-up point, BMI level showed no significant difference according to operation type. Despite this, the degree of weight loss tended to be greater after total gastrectomy than after subtotal gastrectomy.

Figure 1.

Changes in body mass index and serum biochemical data after gastric cancer surgery according to the follow-up periods and operation type. A: Body mass index; B: Fasting blood glucose level; C: HbA1c; D: Insulin; E: C-peptide; F: Homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance; G: Triglyceride; H: Low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; I: High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

The FBS levels at 3, 6 and 12 mo after surgery were lower than preoperative levels, and the difference in FBS levels at the preoperative time point and 12 mo after STG BI (P = 0.001) was statistically significant. As shown in Figure 1B, FBS levels decreased markedly up to 3 or 6 mo after surgery and then slowly declined or increased again up to 12 mo. There was no difference in the FBS level according to operation type at the same time points.

HbA1c levels improved 3 mo after each type of surgery, but increased 12 mo after subtotal gastrectomy and were maintained after total gastrectomy (Figure 1C). Therefore, there were no significant differences between preoperative and postoperative 12-mo HbA1c levels following the three types of surgery. This may be associated with the stabilization of BMI and FBS levels between 3 and 12 mo after surgery, which would result from an increase in food intake. Insulin levels rapidly decreased 3 mo after all types of surgery and then slowly decreased up to 12 mo (Figure 1D).

There were significant differences in insulin and C-peptide levels (Figure 1E) between 3 and 12 mo after surgery, but there were no differences according to operation type at the same follow-up points. HOMA-IR levels consistently improved at 3, 6 and 12 mo after all types of surgery (Figure 1F) and the levels at 12 mo after surgery were significantly lower than the preoperative levels. The HOMA-IR level at 6 mo follow-up after total gastrectomy was significantly lower than that after subtotal gastrectomy.

The lipid profile which included triglyceride, LDL, and HDL did not show significant differences between preoperative and postoperative 12-mo levels, with the exception of HDL level in the STG BI group (Figure 1G-I).

Diabetes control after surgery

Patients were divided into three groups based on their diabetes status: stationary, improved and remission (Table 3). Among the 64 patients, 35 patients (54.7%) improved and 2 patients (3.1%) went into remission. In the STG BI group, 58.3% of patients had improved 12 mo after surgery and 16.7% of patients stopped their medication. However, no patients went into remission. In the STG BII group, one (6.2%) of 16 patients went into remission and 9 (56.2%) were improved 12 mo after surgery. In the TG group, 5 (41.7%) patients were improved and one (8.3%) was in remission 12 mo after surgery. Three (25%) patients stopped medication.

Table 3.

Degree of diabetes mellitus control after surgery n (%)

|

STG BI (n = 36) |

STG BII (n = 16) |

TG (n = 12) |

|||||||

| 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 12 mo | |

| Stationary | 16 (44.4) | 16 (44.4) | 15 (41.7) | 8 (50) | 8 (50) | 6 (37.5) | 6 (50) | 7 (58.3) | 6 (50) |

| Improved | 19 (52.8) | 20 (62.5) | 21 (58.3) | 8 (50) | 8 (50) | 9 (56.2) | 6 (50) | 4 (33.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| Remission | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.2) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| Medication stopped | 6 (16.7) | 6 (16.7) | 6 (16.7) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25) | 3 (25) | 3 (25) | 3 (25) |

Stationary: No change in medication, or patients except improved and remission criteria; Improved: Reduced medication and a reduction in fasting blood glucose (FBS) or HbA1c; Remission: No medication and FBS < 126 mg/dL and HbA1c < 6.0%. STG BI: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis; STG BII: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis; TG: Total gastrectomy.

Factors for diabetes control 12 mo after surgery

We compared the improved and in remission patients to those who were stationary to identify predictive factors for diabetes control. Age, sex, change in BMI, smoking, alcohol history, familial history (1st degree relatives) of type 2 DM, operation type, preoperative fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, insulin, C-peptide, HOMA-IR, triglyceride, LDL, and HDL were not associated with the degree of diabetes control 12 mo after gastrectomy (Table 4). Postoperative BMI changes, smoking history, and the duration of type 2 DM were predictive factors for diabetes control after surgery. BMI levels 3-, 6- and 12-mo after surgery were lower, the incidence of non-smokers was higher, and the duration of DM was shorter in patients satisfying improved or remission criteria than those in the stationary group.

Table 4.

Factors for diabetic control at postoperative 12 mo n (%)

| Stationary (n = 27) | Improved or remission (n = 37) | 1P (univariate) | |

| Age (yr) | 64.3 ± 7.2 | 62.2 ± 8.4 | 0.5822 |

| Sex | 0.789 | ||

| Male | 19 (44.2) | 24 (55.8) | |

| Female | 8 (38.1) | 13 (61.9) | |

| BMI, preop (kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 4.0 | 24.9 ± 3.0 | 0.4342 |

| BMI | |||

| 3 mo | 94.4% ± 5.0% | 91.2% ± 5.3% | 0.0182 |

| 6 mo | 93.7% ± 6.8% | 90.4% ± 5.7% | 0.0362 |

| 12 mo | 93.8% ± 9.1% | 88.9% ± 7.8% | 0.0412 |

| Smoking | 0.043 | ||

| Yes | 16 (57.1) | 12 (42.9) | |

| No | 11 (30.6) | 25 (69.4) | |

| Alcohol history | 0.132 | ||

| No | 13 (34.2) | 25 (65.8) | |

| Yes | 14 (53.8) | 12 (46.2) | |

| DM duration (yr) | 0.013 | ||

| > 10 | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | |

| 5-10 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | |

| < 5 | 9 (29.0) | 22 (71.0) | |

| Family history of DM | 1.000 | ||

| No | 22 (42.3) | 30 (57.7) | |

| Yes | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | |

| Operation type | 0.799 | ||

| STG BI | 15 (41.7) | 21 (58.3) | |

| STG BII | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | |

| TG | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | |

| Preop FBS | 152.1 ± 43.6 | 145.6 ± 40.3 | 0.6242 |

| Preop HbA1c | 6.9 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 0.3132 |

| Preop Insulin | 21.7 ± 26.3 | 19.0 ± 17.8 | 0.8042 |

| Preop C-peptide | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 0.5092 |

| Preop HOMA-IR | 9.2 ± 12.8 | 7.3 ± 8.0 | 0.8352 |

1 χ2;

Mann-Whitney U test, mean ± SD. Significant values are indicated in bold face. BMI: Body mass index, BMI (%) refers to the percentage of BMI at postoperative follow-up. DM: Diabetes mellitus; STG BI: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis; STG BII: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis; TG: Total gastrectomy; FBS: Fasting blood glucose; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance.

In multivariate analysis, the duration of DM was the only significant factor associated with postoperative diabetic control (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of predictive factors for diabetic control at postoperative 12 mo

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95%CI | 1P |

| Sex | |||

| Male | |||

| Female | 0.168 | 0.018-1.529 | 0.113 |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | |||

| No | 12.636 | 0.946-124.216 | 0.068 |

| BMI (%) | |||

| 3 mo | 0.869 | 0.690-1.094 | 0.232 |

| 6 mo | 0.839 | 0.626-1.125 | 0.240 |

| 12 mo | 1.055 | 0.893-1.246 | 0.526 |

| DM duration (yr) | |||

| > 10 | |||

| 5-10 | 27.505 | 2.174-347.988 | 0.010 |

| < 5 | 10.583 | 0.808-138.670 | 0.072 |

| Operation type | |||

| STG BI | |||

| STG BII | 0.547 | 0.086-3.493 | 0.523 |

| TG | 0.088 | 0.006-1.365 | 0.088 |

1Binary logistic regression. STG BI: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth I anastomosis; STG BII: Subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis; TG: Total gastrectomy.

DISCUSSION

In recent studies which evaluated diabetes resolution after gastric cancer surgery, diabetes remitted in 15.1%-19.7% of gastric cancer patients[11,12]. However, because these studies involved a retrospective review of medical records or interviewing, the available laboratory and physical parameters were limited. Although data analysis of the present study was performed retrospectively, all of our data were collected prospectively including laboratory data, body weight change, medical and familial history, and medication status. The low rate of diabetic remission in our study (3.1%) may be due to the strict evaluation of parameters reflecting diabetic control status at an exact time point, 12 mo after surgery.

The BMI of patients decreased by approximately 10% in the first 3 mo after surgery and was maintained or slightly decreased until the 12-mo evaluation. The FBS level showed rapid improvement at 3 mo and then slowed or was maintained up to 12 mo. HbA1c levels decreased at 3 mo and then increased or maintained between 3 and 12 mo after surgery. These patterns were similar in all three types of surgery and may be associated with the increased calorie intake and general recovery that occurs 3 mo after gastrectomy. These results suggest that weight loss is an important factor for diabetes improvement after gastric cancer surgery. Because one of the main treatments for type 2 diabetes is reduced calorie intake and gastrectomy is a type of restrictive surgery, our results are not unexpected[13].

However, serum insulin, C-peptide, and HOMA-IR continuously improved to at least 12 mo after surgery, even if the rate of improvement slowed 3 mo postoperatively. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, insulin, C-peptide, and HOMA-IR levels were significantly lower at the 12-mo evaluation compared to preoperative levels in all operation types. This suggests that insulin resistance continued to improve after surgery up to 12 mo, although body weight, FBS, and HbA1c did not. Gastric cancer surgery, including gastric resection with or without bypass procedures of a short segment of the proximal small bowel, appears to have a beneficial metabolic influence on diabetes control. However, considering that the pattern of biochemical data was similar in the STG BI and STG BII group, incomplete bypass of a short segment of proximal small bowel (BII) did not seem to provide significant additional benefits in terms of glucose metabolism.

The need for and amount of diabetes medication, FBS levels, and HbA1c levels are convenient tools for evaluating the impact of gastric cancer surgery on glucose control in clinical practice. We divided patients into three groups (stationary, improved, and remission) based on the severity of diabetes after surgery. Thirty three (51.6%) of 64 patients had improved glycemic control 3 mo after surgery and this increased to 54.7% 12 mo after surgery. One patient went into remission 3 mo after STG BI, however, this patient did not satisfy remission criteria at the 12 mo evaluation time. Finally, only 2 patients were in remission 12 mo after surgery: one (6.2%) in the STG BII group and the other (8.3%) in the TG group. It seems to be difficult to adequately control diabetes with gastric cancer surgery to stop medication.

As shown in Table 5, the predictive factor for diabetes control 12 mo after surgery was the duration of diabetes. In univariate analysis, the rate of BMI change, smoking history, and diabetes duration were associated with diabetes control 12 mo after surgery. In multivariate analysis, diabetes was controlled in gastric patients with a shorter duration of diabetes. This result was similar to previous reports of type 2 DM patients who took oral hypoglycemic agents and for those who received bariatric surgery[14,15]. It is possible that islet cell function is less impaired in patients with a shorter duration of diabetes than in patients with a longer duration. Therefore, diabetes control would be more effective in gastric cancer patients with a short history of diabetes. The operation type which reflects the extent of gastric resection and the presence of bypass of a short segment of proximal jejunum, were not associated with diabetes control 12 mo after surgery. Although we failed to identify a difference in the efficacy of diabetes control based on the type of gastric cancer surgery, we did find that gastric cancer surgery positively affected diabetes. Although only 3.1% of the 64 patients went into remission, 57.8% showed improved glycemic control after surgery. Considering that approximately 10% of the general population suffers from diabetes and the incidence of diabetes in gastric cancer patients is similar to that of the general population, an improvement in diabetes after gastric cancer surgery would reduce health-care costs and improve the quality of life of these individuals.

Because more than half of the patients in this study were not obese, the impact of gastrectomy described should not be interpreted as if resulting from bariatric surgery. This study was initially planned to help surgeons select the most effective gastric cancer surgery for gastric cancer patients with diabetes. In other retrospective studies, diabetic resolution rates after TG ranged from 27.3%-50%, which were much higher than those after STG BI and BII. However, because the pattern of clinical and laboratory data were similarly changed in all three groups, we could not identify a difference between the STG BI and STG BII groups or between the STG and TG groups. Considering that the gap in HbA1c, insulin, C-peptide, and HOMA-IR levels between STG and TG widened at postoperative 6 mo, TG seemed to have more potential for better and more persistent glucose control than STG. However, they showed no significant difference at postoperative 12 mo and we cannot clarify whether the extent of gastrectomy or bypass length was more important in this study. We did not include patients who had STG with Roux-en-Y reconstruction which can provide a longer and complete bypass length of proximal jejunum than STG BI and BII. As the extent of gastrectomy mainly depends on the tumor location and extent, and the length of bypass of proximal small bowel is very short in conventional gastric cancer surgery, the modification of bypass length of proximal small bowel would offer a better outcome for diabetic control. Therefore, a study that includes a larger number of patients and other types of surgery will be necessary to identify any differences between the types of gastric cancer surgery. In addition, we did not determine postprandial glucose and insulin level, thus we calculated only the insulin sensitivity index using a fasting-based formula. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate the effect of gastric cancer surgery on gastric cancer patients with type 2 DM using an insulin sensitivity index derived from the oral glucose tolerance test.

In conclusion, gastric cancer surgery led to weight loss and a significant improvement in type 2 DM during the first year after surgery. The degree of diabetes control was related to diabetes duration in each patient. However, the impact of operation type in conventional gastric cancer surgery, such as the extent of gastric resection and current reconstruction methods, on diabetes remains to be determined.

COMMENTS

Background

Due to the increased incidence of early gastric cancers and improved survival, postoperative quality of life has become very important after gastric cancer surgery. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an important health problem worldwide and in gastric cancer patients with DM.

Research frontiers

After gastric cancer surgery, many surgeons focus on improving the nutritional status of patients rather than controlling diabetes as the main problem after gastric cancer surgery is weight loss. Therefore, the effect of gastric cancer surgery on diabetic control in gastric cancer patients with type 2 DM has not yet been fully evaluated. In this study, the authors demonstrated the short-term effect of three types of routine gastric cancer surgery on type 2 DM.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this study, the organized serial evaluation of the status of diabetic control was prospectively performed according to surgical extent and reconstruction type in conventional gastric cancer surgery.

Applications

This study will allow surgeons to select a favorable reconstruction type after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with diabetes.

Peer review

The study showed that diabetes mellitus was improved in more than 50% of patients during the first year after gastric cancer surgery and the degree of diabetes control was related to diabetes duration and not with the surgical type. However, the effect of gastric cancer surgery type on diabetic control should be further evaluated. These results are very original and support the possibilities that gastric surgery may be an alternative in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Footnotes

Supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2011-0011301; a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Medicine for 2011, 6-2011-0084

P- Reviewers: Ali O, Chien KL, Gómez-Sáez J S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Lee JY, Park EC, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2008. Cancer Res Treat. 2011;43:1–11. doi: 10.4143/crt.2011.43.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Information Center. Accessed on 2 May 2012. Available from: http://www.cancer.go.kr/ncic/cics_b/01/013/1268111_5873.html.

- 3.The Information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. 2004 Nationwide Gastric Cancer Report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2007;7:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sim YK, Kim CY, Jeong YJ, Kim JH, Hwang Y, Yang DH. Changes of the Clinicopathological Characteristics and Survival Rates of Gastric Cancer with Gastrectomy - 1990s vs early 2000s. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2009;9:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Statistics Korea. Statistics of Cause of Death. Available from: http://www.kostat.go.kr. Accessed on 2 May 2012.

- 6.Kim SG, Choi DS. The Present State of Diabetes Mellitus in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2008;51:791–798. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schauer PR, Burguera B, Ikramuddin S, Cottam D, Gourash W, Hamad G, Eid GM, Mattar S, Ramanathan R, Barinas-Mitchel E, et al. Effect of laparoscopic Roux-en Y gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2003;238:467–484; discussion 84-85. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000089851.41115.1b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, Barakat HA, deRamon RA, Israel G, Dolezal JM. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339–350; discussion 350-352. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee WJ, Chong K, Chen CY, Chen SC, Lee YC, Ser KH, Chuang LM. Diabetes remission and insulin secretion after gastric bypass in patients with body mass index & lt; 35 kg/m2. Obes Surg. 2011;21:889–895. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s101200200000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JW, Cheong JH, Hyung WJ, Choi SH, Noh SH. Outcome after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with type 2 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:49–54. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee W, Ahn SH, Lee JH, Park do J, Lee HJ, Kim HH, Yang HK. Comparative study of diabetes mellitus resolution according to reconstruction type after gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with diabetes mellitus. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1238–1243. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, Bantle JP, Sledge I. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248–256.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaku K, Kawasaki F, Kanda Y, Matsuda M. Retained capacity of glucose-mediated insulin secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inversely correlates with the duration of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004;64:221–223. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim MK, Lee HC, Lee SH, Kwon HS, Baek KH, Kim EK, Lee KW, Song KH. The difference of glucostatic parameters according to the remission of diabetes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28:439–446. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]