Abstract

Ethanol ingestion increases endogenous glucocorticoid levels in both humans and rodents. The present study aimed to define a mechanistic link between the increased glucocorticoids and alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Plasma corticosterone levels were not affected in mice on a 2-wk ethanol diet regimen but significantly increased upon 4 wk of ethanol ingestion. Accordingly, hepatic triglyceride levels were not altered after 2 wk of ethanol ingestion but were elevated at 4 wk. Based on the observation that 2 wk of ethanol ingestion did not significantly increase endogenous corticosterone levels, we administered exogenous glucocorticoids along with the 2-wk ethanol treatment to determine whether the elevated glucocorticoid contributes to the development of alcoholic fatty liver. Mice were subjected to ethanol feeding for 2 wk with or without dexamethasone administration. Hepatic triglyceride contents were not affected by either ethanol or dexamethasone alone but were significantly increased by administration of both. Microarray and protein level analyses revealed two distinct changes in hepatic lipid metabolism in mice administered with both ethanol and dexamethasone: accelerated triglyceride synthesis by diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 and suppressed fatty acid β-oxidation by long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a, and acyl-CoA oxidase 1. A reduction of hepatic peroxisome proliferation activator receptor-α (PPAR-α) was associated with coadministration of ethanol and dexamethasone. These findings suggest that increased glucocorticoid levels may contribute to the development of alcoholic fatty liver, at least partially, through hepatic PPAR-α inactivation.

Keywords: alcoholic fatty liver, glucocorticoids, lipid metabolism

heavy alcohol consumption is a significant cause of liver disease. Alcoholic liver disease is a multifactor and multistep process that typically involves progression through different stages, such as fatty liver (also called hepatic steatosis), steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (4, 16). Although the association between alcohol intake and alcoholic liver disease has been well documented, the precise molecular mechanisms that underlie the development of liver injury are still not completely understood.

Liver injury caused by alcohol is attributed to alcohol metabolism in the hepatocytes. Alcohol is first converted to acetaldehyde by cytosolic alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), microsomal cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1), and/or peroxisomal catalase, and then to acetate by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) in the mitochondria. This two-step metabolic process results in an increased ratio of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) to NAD+ and elevated levels of the toxic intermediate acetaldehyde and/or reactive oxygen species that can induce hepatocyte injury (7, 30). In addition to liver damage, other organs and systems are also affected by excessive alcohol consumption, including adipose tissue (50, 53, 56, 57), the gastrointestinal tract (22), the respiratory tract (6, 51), muscles (15), and the immune (16, 54) and endocrine systems (14). Alcohol can impair the functions of the endocrine system, thereby causing nonphysiological increase or decrease of hormone release and the concomitant dysregulated signaling on target tissues.

Previous studies demonstrated that acute or chronic ethanol ingestion causes a significant increase of endogenous glucocorticoid levels in both humans and rodents (1, 2, 5, 8, 12, 13, 37, 45, 52, 55, 58). Glucocorticoids are a class of steroid hormones that are secreted by cortical cells in the zona fasciculata of the adrenal gland (46). The main glucocorticoid in humans is cortisol. Rodents are unable to synthesize cortisol due to the lack the 17α-hydroxylase enzyme required for hydroxylation of pregnenolone for cortisol synthesis, and, in rodents, the principal glucocorticoid is corticosterone. The production of glucocorticoids is controlled by pituitary adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) via a positive-feedback mechanism. Glucocorticoids induce their physiological functions through binding to intracellular glucocorticoid receptors (GRs), which are classified into three subtypes, α, β and γ. Upon ligand binding, the active GR-α translocates into the nucleus and either binds glucocorticoid response elements (GREs) in the promoter regions of glucocorticoid-inducible genes or cooperates with other transcription factors to affect transcription (34, 47, 49). Extended use of glucocorticoids can lead to numerous side effects, one of the most dangerous being suppression of the immune system (34, 36, 48). Indeed, synthetic glucocorticoids are often used as anti-inflammatory therapeutic drugs. Although the increased release of glucocorticoids by ethanol may cause immunosuppression, their impact on hepatic lipid metabolism and possible mechanisms have not been well defined.

In the present study, we administered ethanol and the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone to mice and used microarray analyses and protein expression studies to elucidate mechanistic insights into the role of increased glucocorticoid in the development of alcoholic fatty liver.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and treatments.

All mice were treated according to the experimental procedures approved by the North Carolina Research Campus Animal Care and Use Committee. Male C57BL/6N mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed singly under a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle on a standard rodent chow diet until experimental analysis. Twelve-week-old mice were pair fed with modified Lieber-DeCarli liquid diets (BioServ, Frenchtown, NJ) containing either ethanol or isocaloric maltose dextrin as a control. The control liquid diet provided 49% total energy from carbohydrate, 35% from fat, and 16% from protein. The carbohydrate calories were partially replaced by ethanol in the ethanol diet as described below. After 8 days of prefeeding, the ethanol-fed mice were given the ethanol liquid diet containing 4.7% ethanol (wt/vol, 34% of total calories) for weeks 1 and 2 (for the 2-wk treatment), 4.9% (wt/vol, 35% of total calories) for week 3, and 5.1% (wt/vol, 37% of total calories) for week 4 (for the 4-wk treatment). Food intake was monitored daily. The ethanol group mice were fed ad libitum. The controls were given the control liquid diet in the amount consumed by the ethanol-fed mice in the prior day.

For the time-course analysis, mice were subjected to either a 2-wk or 4-wk ethanol-fed or control diet. In the second experiment, mice were exposed to ethanol for 2 wk with or without dexamethasone administration. The amount of dexamethasone in the liquid diet was adjusted twice a week according to food intake and body weight change to maintain the dexamethasone dose at 3 mg/kg per day. At the end of the experiments, mice were euthanized with isofluorane after 4 h of fasting. Blood was drawn from inferior vena cava, decanted into a tube containing heparin, and immediately put on ice. The liver was rapidly removed, weighed, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Plasma and liver samples were stored at −80°C until use.

Blood parameters assay.

Blood glucose was measured using the OneTouch Ultra2 blood glucose meter (Life Scan, Milpitas, CA). Blood ketone bodies were determined using a CardioCheck analyzer with PTS Panels ketone test strips (Polymer Technology Systems, Indianapolis, IN). Plasma triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations were measured using the Triglyceride Reagent and Cholesterol Reagent (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), respectively. The concentration of plasma free fatty acids (FFA) was determined with a FFA Quantification Kit (BioVision, Mountain View, CA). Insulin, adiponectin, and leptin levels were determined using ELISA kits (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Corticosterone levels were measured with an ELISA kit from Enzo Life Sciences (New York, NY).

Determination of liver injury.

To examine liver injury, plasma liver enzyme activity, liver histopathology, and lipid concentrations were assessed. The activities of plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were colorimetrically measured using ALT Reagent and AST Reagent (Thermo Scientific), respectively. Liver frozen tissue sections were prepared and stained with an Oil red O kit (American MasterTech Scientific, Lodi, CA). Quantitative analysis of hepatic lipids was conducted by measuring the concentrations of triglyceride, cholesterol, and FFA in the liver tissues as described previously (53).

RNA isolation and microarray analyses.

Total hepatic RNA was isolated by TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The integrity of each RNA sample was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Foster City, CA), and RNA quantity was determined using a Nanodrop 2000. Microarray analysis was performed with mouse WG-6 v2.0 expression beadchips (Illumina, San Diego, CA) by the Genomics Laboratory at David H. Murdock Research Institute (Kannapolis, NC). Three microarrays were used for each group.

Raw microarray data analyses were preprocessed, and quality was assessed. The unnormalized probe-level intensity data were processed using quantile normalization. Multiple probes mapping to the same gene were then merged into a unified expression index. The latest gene annotation information was retrieved from multiple public databases, including Entrez Gene, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), and Gene Ontology (GO).

One type of pairwise comparison was performed on the processed data: ethanol plus dexamethasone vs. ethanol. In the comparison, two types of analysis were performed: 1) pathways or gene set analysis, which selects the most significantly perturbed KEGG pathways, and 2) individual gene analysis (or differentially expressed gene analysis), which selects the most differentially expressed individual genes. Gene set or pathway analysis was performed using generally applicable gene set enrichment (GAGE) (32). The perturbed KEGG pathways were selected with false discovery rate (FDR) q value <0.1. Individual gene analysis selected differentially regulated genes with FDR q value <0.1 using a nonparametric rank test based on GAGE (32). Gene expression perturbation patterns within each selected KEGG pathway were analyzed and visualized using the novel Pathview software package (33).

qRT-PCR.

After isolation of total RNA, samples were reverse transcribed with TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The expression levels of genes were measured in triplicate by the comparative cycle threshold method using a 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The primer sets for quantitative real-time PCR were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA): GR-α forward (F) 5′-AGCTCCCCCTGGTAGAGAC-3′, reverse (R) 5′-GGTGAAGACGCAGAAACCTTG-3′; 18s rRNA F 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′, R 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGGG-3′. The data were normalized to 18s rRNA expression levels and presented as relative changes, setting the values of control mice as 1.

Western blot.

Liver proteins were extracted by tissue protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein extracts were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The membrane was probed with primary antibodies (suppliers available upon request). Following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Scientific), proteins were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Thermo Scientific) and quantified by densitometry analysis.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse CYP 2E1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight at 4°C. After being washed, the tissue sections were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature. Finally, the immunoreactivities were visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was determined by ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison.

RESULTS

Chronic and excessive ethanol ingestion induced alcoholic fatty liver and increased endogenous corticosterone levels.

As shown in Table 1, mice significantly lost body weight after ethanol ingestion, whereas pair-fed controls showed body weight gain. The body weight of ethanol-fed mice was significantly lower than the controls at both the 2-wk and 4-wk time points. However, the body weight of ethanol-fed mice at the 4-wk time point was not further reduced compared with the 2-wk time point. A significant decrease of liver weight was found at the 2-wk time point but not at the 4-wk time point. Ethanol ingestion significantly reduced blood glucose levels at both 2 and 4 wk and lowered insulin levels at 4 wk. Ethanol ingestion did not affect plasma triglyceride or FFA levels but did reduce plasma cholesterol levels and increased plasma ketone body levels at both the 2-wk and 4-wk time points. In ethanol-fed mice, plasma adiponectin concentrations were significantly increased at 2 wk but declined to normal levels at 4 wk, whereas plasma leptin level was significantly decreased at both 2-wk and 4-wk time points.

Table 1.

Effects of ethanol on body weight, liver weight, and some blood parameters in mice at 2-wk or 4-wk time point

| 2 Weeks |

4 Weeks |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Ethanol | Control | Ethanol | |

| Initial body weight, g | 27.6 ± 1.32 | 27.1 ± 0.5 | 26.7 ± 0.6 | 27.5 ± 1.3 |

| Final body weight, g | 30.4 ± 2.5a* | 23.5 ± 0.9b* | 31.9 ± 0.8a* | 24.9 ± 1.4b* |

| Liver weight, g | 1.240 ± 0.145a* | 1.021 ± 0.063b* | 1.223 ± 0.052a* | 1.111 ± 0.096ab* |

| Blood parameters | ||||

| Glucose, mg/dl | 311 ± 54a | 194 ± 47bc | 264 ± 47ab | 148 ± 60c |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.607 ± 0.077a | 0.323 ± 0.124ab | 0.788 ± 0.119a | 0.264 ± 0.145b |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 97.79 ± 31.06 | 104.05 ± 30.82 | 124.32 ± 29.00 | 93.24 ± 30.76 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 122.34 ± 33.70ac | 92.91 ± 21.06ab | 139.37 ± 4.10c | 84.40 ± 5.65b |

| Free fatty acid, μM | 457.8 ± 95.6 | 538.4 ± 180.6 | 373.3 ± 165.9 | 321.0 ± 122.3 |

| Ketone body, mg/dl | 6.4 ± 1.0a | 12.8 ± 3.6b | 6.0 ± 0.5a | 14.5 ± 3.4b |

| Adiponectin μg/ml | 7.676 ± 0.970a | 13.065 ± 3.112b | 6.001 ± 0.726a | 9.220 ± 1.687ab |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 12.16 ± 3.70a* | 2.94 ± 1.64b* | 21.06 ± 2.63c* | 3.32 ± 3.76b* |

Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk or 4 wk. Data are expressed as means ± SD; n = 5–8. Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

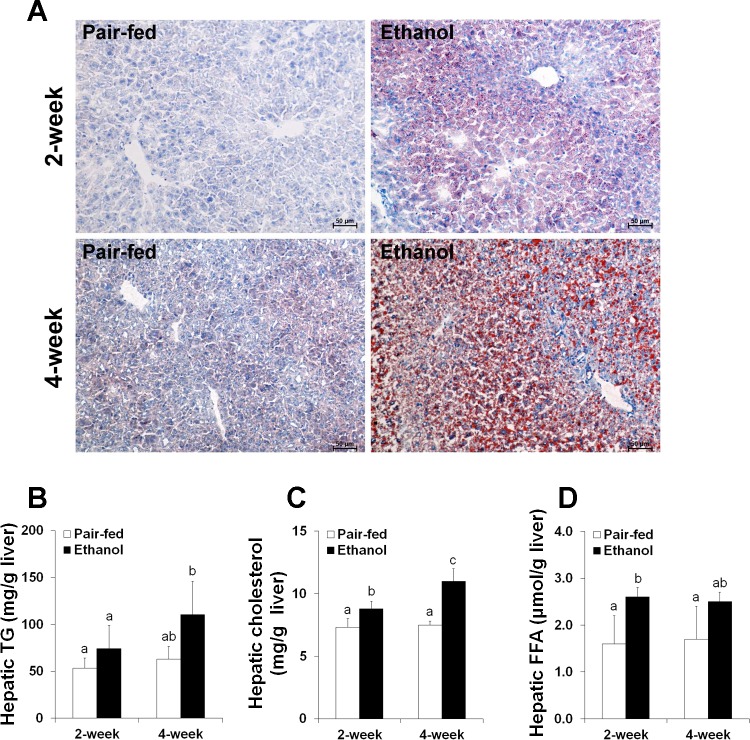

After 2 wk of ethanol ingestion, only small lipid droplets in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (microvesicular steatosis) were observed in the frozen liver section by Oil red O staining. In contrast, large lipid droplets were observed in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (macrovesicular steatosis) after 4 wk (Fig. 1A). Quantitative measurements of hepatic lipids showed that triglyceride concentrations were significantly increased after 4 wk of ethanol ingestion (Fig. 1B). Hepatic cholesterol levels were dramatically elevated after both 2 and 4 wk of ethanol ingestion (Fig. 1C). Hepatic FFA levels were significantly increased after 2 wk of ethanol ingestion compared with the pair-fed controls (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Chronic and excessive ethanol intake induced fatty liver in mice. Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk or 4 wk. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 4–6). Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05. A: liver frozen tissue sections stained with Oil red O. Hematoxylin counterstain. B: hepatic triglyceride (TG) content. C: hepatic cholesterol content. D: hepatic content of free fatty acids (FFA).

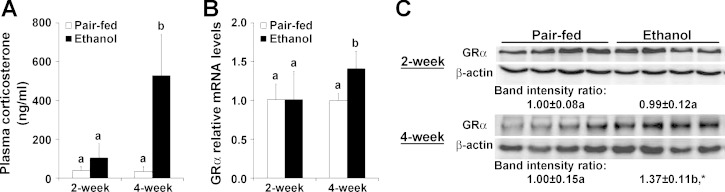

Plasma corticosterone concentrations were not affected by ethanol ingestion at the 2-wk time point but dramatically increased by ∼15-fold in ethanol-fed mice after 4 wk compared with the pair-fed controls (Fig. 2A). The gene expression of GR-α was markedly upregulated in the liver after 4 wk of ethanol ingestion (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the qRT-PCR results, the protein level of GR-α was also increased in the liver after 4 wk of ethanol ingestion compared with the pair-fed controls (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Chronic and excessive ethanol intake induced endogenous corticosterone elevation in mice. Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk or 4 wk. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 4–6). Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05. *P < 0.01. A: plasma corticosterone levels. B: hepatic glucocorticoid receptor-α (GR-α) gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. C: Western blot analysis of GR-α protein expression in the liver of mice fed the ethanol liquid diet.

Dexamethasone exacerbated the development of alcoholic fatty liver in mice.

Based on the above observation that 2 wk of ethanol ingestion did not increase plasma corticosterone levels, we administered dexamethasone along with the 2-wk ethanol treatment to determine whether the elevated glucocorticoid contributes to the development of alcoholic fatty liver. Glucocorticoids were previously reported to affect food intake and body weight (17). In the present study, dexamethasone did not alter daily food intake in ethanol-fed mice (data not shown). Therefore, ethanol alone and ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice consumed the equivalent amount of ethanol in the present study.

As shown in Table 2, mice significantly lost body weight after ethanol ingestion, whereas pair-fed controls showed body weight gain. Dexamethasone administration did not alter body weight in pair-fed control mice but greatly decreased body weight in ethanol-fed mice. Dexamethasone did not significantly change liver weight either in ethanol- or pair-fed mice. Dexamethasone administration also attenuated the ethanol-induced decline of blood glucose and plasma insulin levels. Whereas dexamethasone alone increased plasma triglyceride levels, plasma FFA levels were reduced only by dexamethasone plus ethanol coadministration. Dexamethasone administration significantly inhibited ethanol-induced elevation of plasma ketone body levels. Plasma adiponectin concentrations were significantly increased by ingestion of ethanol alone and greatly increased by ethanol plus dexamethasone coadministration but not affected by ingestion of dexamethasone alone. Although dexamethasone alone increased plasma leptin levels by 1.9-fold, ethanol alone and ethanol plus dexamethasone coadministration dramatically reduced plasma leptin levels by 76% and 71%, respectively.

Table 2.

Effects of ethanol, dexamethasone, or ethanol plus dexamethasone on body weight, liver weight, and some blood parameters in mice

| Control | Ethanol | Dexamethasone | Ethanol+Dexamethasone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial body weight, g | 27.6 ± 1.32 | 27.1 ± 0.5 | 27.1 ± 0.9 | 27.9 ± 1.1 |

| Final body weight, g | 30.4 ± 2.5a | 23.5 ± 0.9b | 27.1 ± 1.7c | 21.6 ± 0.4d |

| Liver weight, g | 1.240 ± 0.145a* | 1.021 ± 0.063b* | 1.331 ± 0.100a* | 1.200 ± 0.118a* |

| Blood parameters | ||||

| Glucose, mg/dl | 311 ± 54a | 194 ± 47b | 270 ± 41ab | 230 ± 90ab |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.607 ± 0.077a* | 0.323 ± 0.124a* | 2.848 ± 0.780b* | 0.543 ± 0.429a* |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 97.79 ± 31.06a | 104.05 ± 30.82a | 163.37 ± 41.70b | 84.00 ± 25.50a |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 122.34 ± 33.70 | 92.91 ± 21.06 | 111.50 ± 29.02 | 96.63 ± 42.59 |

| Free fatty acid, μM | 457.8 ± 95.6a | 538.4 ± 180.6a | 373.9 ± 133.7ab | 228.0 ± 130.2b |

| Ketone body, mg/dl | 6.4 ± 1.0a | 12.8 ± 3.6b | 6.5 ± 1.0a | 7.8 ± 2.1a |

| Adiponectin, μg/ml | 7.676 ± 0.970a | 13.065 ± 3.112b | 8.735 ± 1.716a | 15.660 ± 1.915c |

| Leptin, ng/ml | 12.16 ± 3.70a | 2.94 ± 1.64b | 23.12 ± 7.99c | 3.52 ± 4.62b |

Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk, and dexamethasone was administered in the liquid diet at 3 mg/kg body wt per day. Data are expressed as means ± SD; n = 5–8. Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

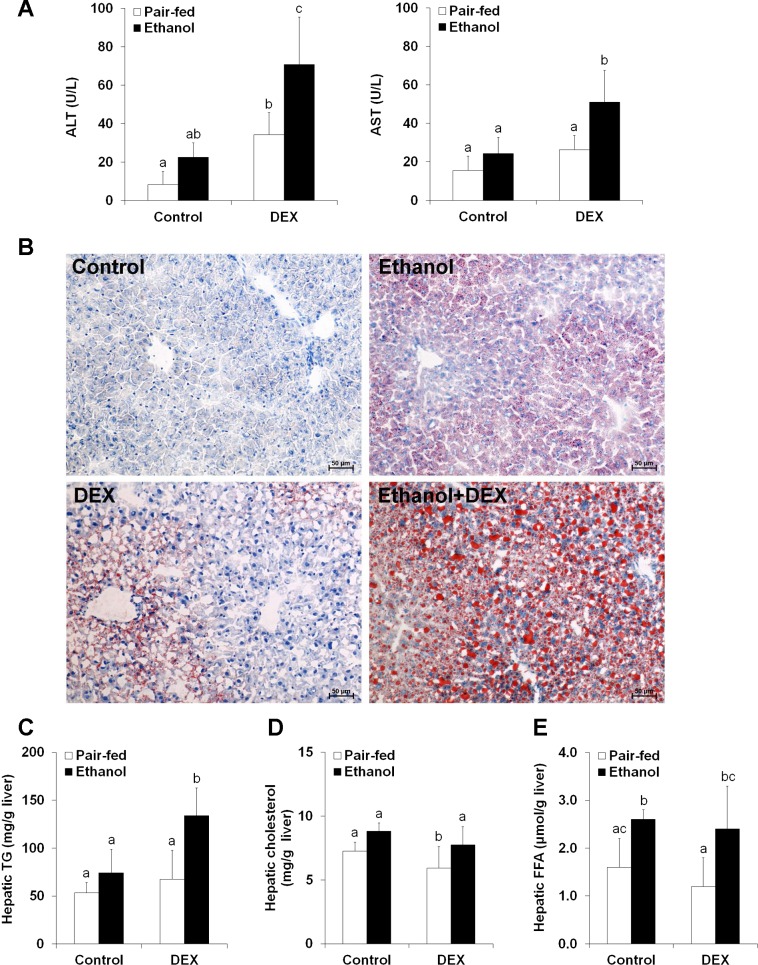

In ethanol plus dexamethasone ingestion mice, plasma ALT and AST levels were dramatically elevated (Fig. 3A). Small lipid droplets were observed in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes in ethanol-fed mice as described in the time-course study. In contrast, numerous large lipid droplets were observed in the cytoplasm of most hepatocytes in ethanol plus dexamethasone ingestion mice (Fig. 3B). Quantitative measurements of hepatic lipids showed that the triglyceride concentrations were significantly increased by ethanol plus dexamethasone compared with ethanol alone (Fig. 3C). However, neither cholesterol levels nor FFA levels were different between ethanol alone and ethanol plus dexamethasone treatments (Fig. 3, D and E).

Fig. 3.

Dexamethasone (DEX) exacerbated the development of alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk, and DEX was administered in the liquid diet at 3 mg/kg body wt per day. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 4–6). Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05. A, left: plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. Right: plasma aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels. B: liver frozen tissue sections stained with Oil red O. Hematoxylin counterstain. C: hepatic TG content. D: hepatic cholesterol content. E: hepatic content of FFA.

Dexamethasone altered the expression of genes related to lipid metabolism in ethanol-fed mouse liver.

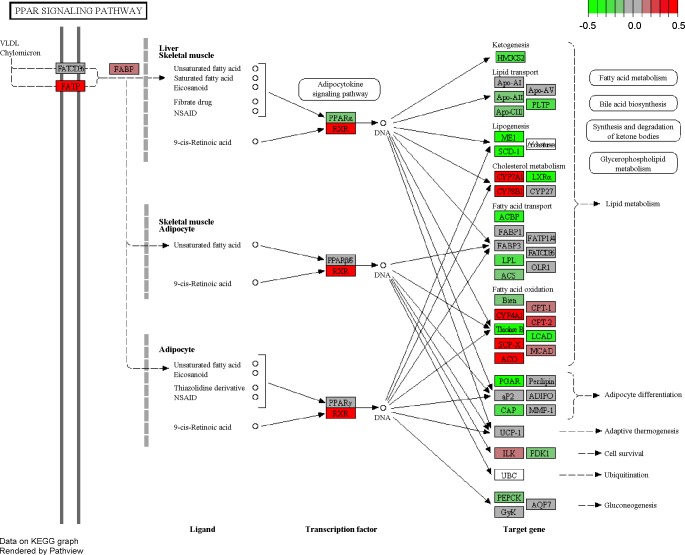

GAGE analysis identified significantly perturbed KEGG pathways (FDR q value <0.1) in either one direction (up or down) or both directions (two-way) simultaneously. Results in the ethanol + dexamethasone mice compared with the ethanol mice are listed in Table 3. The pathways identified as significantly perturbed were classified into lipid metabolism-related pathways or lipid metabolism-nonrelated pathways. Among the lipid metabolism-related pathways, steroid hormone biosynthesis and primary bile acid biosynthesis were significantly upregulated. Others included the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) signaling, fatty acid metabolism, and oxidative phosphorylation pathways (upregulated and downregulated simultaneously). Among the lipid metabolism-nonrelated pathways, protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum, complement, and coagulation cascades and protein export pathways were significantly upregulated. Other significantly perturbed pathways included drug metabolism-cytochrome P450 and drug metabolism-other enzymes. Individual gene analysis identified 3,958 significantly changed genes (1,939 upregulated; 2,019 downregulated) in the ethanol + dexamethasone mice compared with the ethanol mice (FDR q value <0.1). The PPAR signaling pathway was identified as a critical node of regulation by dexamethasone administration in ethanol-fed mouse liver, and the individual genes in the PPAR signaling pathway significantly altered in response to dexamethasone are summarized in Table 4. The other perturbed genes in lipid metabolism-related pathways are listed in Supplemental Table S1; supplemental material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology website. The expression pattern of genes in the PPAR signaling pathway is visualized in Fig. 4.

Table 3.

The altered pathways (gene sets) by dexamethasone administration in ethanol-fed mouse liver via microarray analysis (ethanol plus dexamethasone vs. ethanol)

| Gene Set, KEGG Pathway | q Value | Set Size |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid metabolism-related | ||

| Upregulated | ||

| Mmu00140 Steroid hormone biosynthesis | 0.0593 | 52 |

| Mmu00120 Primary bile acid biosynthesis | 0.0593 | 15 |

| Two-way perturbed | ||

| Mmu00830 Retinol metabolism | 0.0000 | 70 |

| Mmu04146 Peroxisome | 0.0000 | 77 |

| Mmu03320 PPAR signaling pathway | 0.0002 | 73 |

| Mmu00071 Fatty acid metabolism | 0.0004 | 43 |

| Mmu04142 Lysosome | 0.0005 | 115 |

| Mmu00010 Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 0.0006 | 58 |

| Mmu04145 Phagosome | 0.0019 | 158 |

| Mmu00190 Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.0024 | 108 |

| Mmu01040 Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 0.0033 | 23 |

| Mmu00100 Steroid biosynthesis | 0.0034 | 15 |

| Mmu00591 Linoleic acid metabolism | 0.0045 | 43 |

| Mmu00020 Citrate cycle, TCA cycle | 0.0068 | 30 |

| Mmu00561 Glycerolipid metabolism | 0.0105 | 49 |

| Mmu00600 Sphingolipid metabolism | 0.0158 | 39 |

| Mmu00564 Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 0.0354 | 76 |

| Mmu04975 Fat digestion and absorption | 0.0965 | 44 |

| Lipid metabolism nonrelated | ||

| Upregulated | ||

| Mmu04141 Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum | 0.0007 | 150 |

| Mmu04610 Complement and coagulation cascades | 0.0593 | 72 |

| Mmu03060 Protein export | 0.0593 | 23 |

| Two-way perturbed | ||

| Mmu00982 Drug metabolism - cytochrome P450 | 0.0000 | 84 |

| Mmu00983 Drug metabolism - other enzymes | 0.0000 | 55 |

| Mmu00980 Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 0.0000 | 75 |

| Mmu00480 Glutathione metabolism | 0.0001 | 49 |

| Mmu04976 Bile secretion | 0.0001 | 67 |

| Mmu00250 Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism | 0.0002 | 28 |

| Mmu00040 Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 0.0004 | 31 |

| Mmu00260 Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism | 0.0004 | 32 |

| Mmu00650 Butanoate metabolism | 0.0006 | 27 |

| Mmu00590 Arachidonic acid metabolism | 0.0007 | 81 |

| Mmu00860 Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism | 0.0010 | 38 |

| Mmu00280 Valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation | 0.0013 | 46 |

| Mmu00500 Starch and sucrose metabolism | 0.0013 | 43 |

| Mmu00330 Arginine and proline metabolism | 0.0034 | 48 |

| Mmu00270 Cysteine and methionine metabolism | 0.0034 | 32 |

| Mmu04910 Insulin signaling pathway | 0.0089 | 126 |

| Mmu04964 Proximal tubule bicarbonate reclamation | 0.0092 | 18 |

| Mmu00052 Galactose metabolism | 0.0098 | 25 |

| Mmu00630 Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 0.0106 | 18 |

| Mmu00620 Pyruvate metabolism | 0.0106 | 38 |

| Mmu00053 Ascorbate and aldarate metabolism | 0.0115 | 25 |

| Mmu00520 Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 0.0136 | 45 |

| Mmu00380 Tryptophan metabolism | 0.0264 | 42 |

| Mmu00350 Tyrosine metabolism | 0.0326 | 33 |

| Mmu00340 Histidine metabolism | 0.0405 | 25 |

| Mmu00310 Lysine degradation | 0.0422 | 43 |

| Mmu00910 Nitrogen metabolism | 0.0429 | 22 |

| Mmu00030 Pentose phosphate pathway | 0.0455 | 27 |

| Mmu00920 Sulfur metabolism | 0.0503 | 10 |

| Mmu04612 Antigen processing and presentation | 0.0554 | 73 |

| Mmu00900 Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 0.0577 | 12 |

| Mmu04120 Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis | 0.0595 | 129 |

| Mmu02010 ABC transporters | 0.0600 | 44 |

| Mmu00450 Selenocompound metabolism | 0.0627 | 16 |

| Mmu04270 Vascular smooth muscle contraction | 0.0738 | 112 |

| Mmu04710 Circadian rhythm - mammal | 0.0738 | 19 |

| Mmu03010 Ribosome | 0.0738 | 68 |

| Mmu00514 Other types of O-glycan biosynthesis | 0.0738 | 41 |

| Mmu00640 Propanoate metabolism | 0.0773 | 27 |

| Mmu00051 Fructose and mannose metabolism | 0.0773 | 35 |

| Mmu04962 Vasopressin-regulated water reabsorption | 0.0773 | 42 |

| Mmu00760 Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 0.0773 | 26 |

| Mmu04520 Adherens junction | 0.0891 | 69 |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PPAR, peroxisome proliferation activator receptor; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; ABC, ATP-binding cassette.

Table 4.

The altered genes in PPAR signaling pathway and ethanol metabolism by dexamethasone administration in ethanol-fed mouse liver via microarray analysis (ethanol plus dexamethasone vs. ethanol)

| EnterzGen | Symbol | q Value | log2, fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mmu03320 PPAR signaling pathway | |||

| 20249 | Scd1 | 0.0001 | −4.159 |

| 13124 | Cyp8b1 | 0.0004 | 1.433 |

| 17436 | Me1 | 0.0026 | −0.999 |

| 13122 | Cyp7a1 | 0.0030 | 0.632 |

| 235674 | Acaa1b | 0.0046 | −1.281 |

| 57875 | Angptl4 | 0.0072 | −1.024 |

| 20280 | Scp2 | 0.0100 | 0.961 |

| 433256 | Acsl5 | 0.0109 | −0.319 |

| 93732 | Acox2 | 0.0140 | 0.379 |

| 22259 | Nr1 h3 | 0.0166 | −0.361 |

| 20182 | Rxrβ | 0.0175 | 0.143 |

| 80911 | Acox3 | 0.0206 | 0.064 |

| 11363 | Acadl | 0.0210 | 0.168 |

| 26458 | Slc27a2 | 0.0240 | 0.294 |

| 74205 | Acsl3 | 0.0256 | 0.553 |

| 113868 | Acaa1a | 0.0303 | 0.025 |

| 13167 | Dbi | 0.0325 | −0.264 |

| 20411 | Sorbs1 | 0.0346 | −0.237 |

| 15360 | Hmgcs2 | 0.0431 | −0.375 |

| 12896 | Cpt2 | 0.0463 | 0.115 |

| 18830 | Pltp | 0.0472 | −0.353 |

| 16956 | Lpl | 0.0489 | −0.254 |

| 11430 | Acox1 | 0.0544 | 0.127 |

| 19013 | Pparα | 0.0799 | −0.107 |

| 12894 | Cpt1a | 0.0809 | 0.090 |

| 11807 | Apoa2 | 0.0878 | 0.057 |

| 18607 | Pdpk1 | 0.0884 | −0.130 |

| Mmu00830 Retinol metabolism-ethanol metabolism | |||

| 26876 | Adh4 | 0.0022 | 0.909 |

| 11522 | Adh1 | 0.0455 | −0.286 |

| 11529 | Adh7 | 0.0503 | 0.376 |

| Mmu00561 Glycerolipid metabolism-ethanol metabolism | |||

| 216188 | Aldh1/2 | 0.0847 | −0.119 |

Fig. 4.

The perturbed pattern of genes in the peroxisome proliferation activator receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway by DEX administration (ethanol plus DEX vs. ethanol). Green and red indicate downregulated and upregulated individual genes, respectively. The scale indicates the number of log2 (fold change). VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein; FATP, fatty acid transport protein; FABP, fatty acid binding protein; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RXR, retinoid X receptor; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

Dexamethasone altered the expression of proteins related to lipid metabolism in ethanol-fed mouse liver.

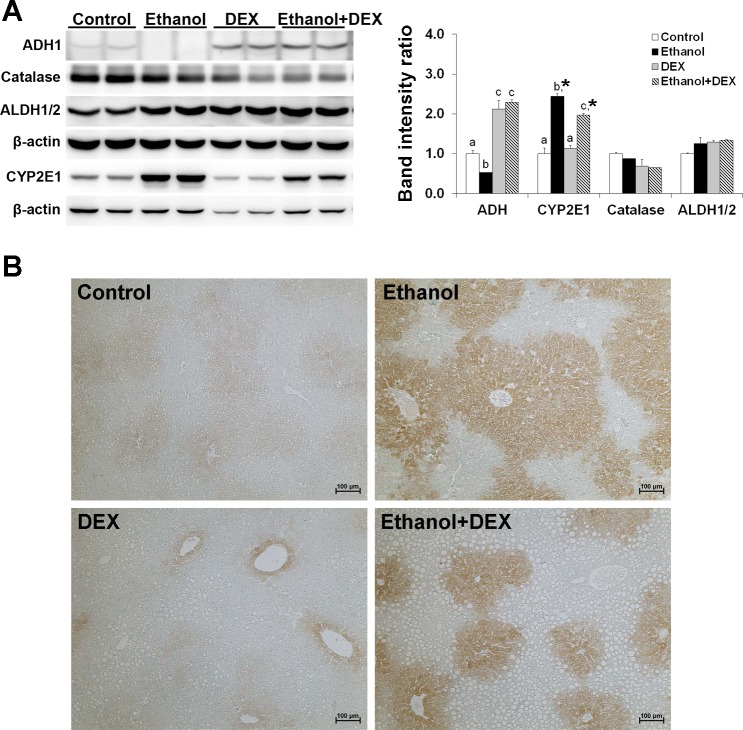

Because gene expression levels often do not parallel the protein levels, we performed independent validation of significantly perturbed genes using Western blot analysis. To obtain better insight into the pathophysiological alterations in the liver after dexamethasone administration, we included several important candidates whose mRNA expression was not significantly changed in the microarray analysis. First, we verified the protein expression of ethanol metabolism enzymes. As shown in Fig. 5, ADH1 was downregulated (0.5-fold) by ethanol ingestion but upregulated (more than 2-fold) by dexamethasone administration, regardless of ethanol ingestion. The levels of CYP 2E1 protein were increased in both ethanol alone- and ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice (≥2.0-fold). The increased CYP2E1 level by ethanol was significantly attenuated by dexamethasone (∼2.0-fold vs. ∼2.5-fold). The results of immunohistochemical staining confirmed that CYP2E1 protein was localized in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes within zone 3 of the liver. The expression of CYP2E1 protein was markedly increased by ethanol, whereas the staining area was reduced by dexamethasone. The protein levels of other ethanol metabolism enzymes, catalase and ALDH1/2, were not significantly altered by either dexamethasone or ethanol ingestion.

Fig. 5.

DEX altered the protein expression of ethanol metabolism enzymes in the mouse liver. Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk, and DEX was administered in the liquid diet at 3 mg/kg body wt per day. A: representative Western blot of liver samples from control (pair-fed), ethanol-, DEX-, and ethanol plus DEX-fed mice. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 2). Means without a common letter differ at *P < 0.05. B: representative immunohistochemical staining of CYP2E1 in the paraffin-embedded sections of the liver tissues from control (pair-fed), ethanol-, DEX-, and ethanol plus DEX-fed mice. ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; ALDH, aldehyde dehydrogenase; CYP2E1, cytochrome P450 2E1.

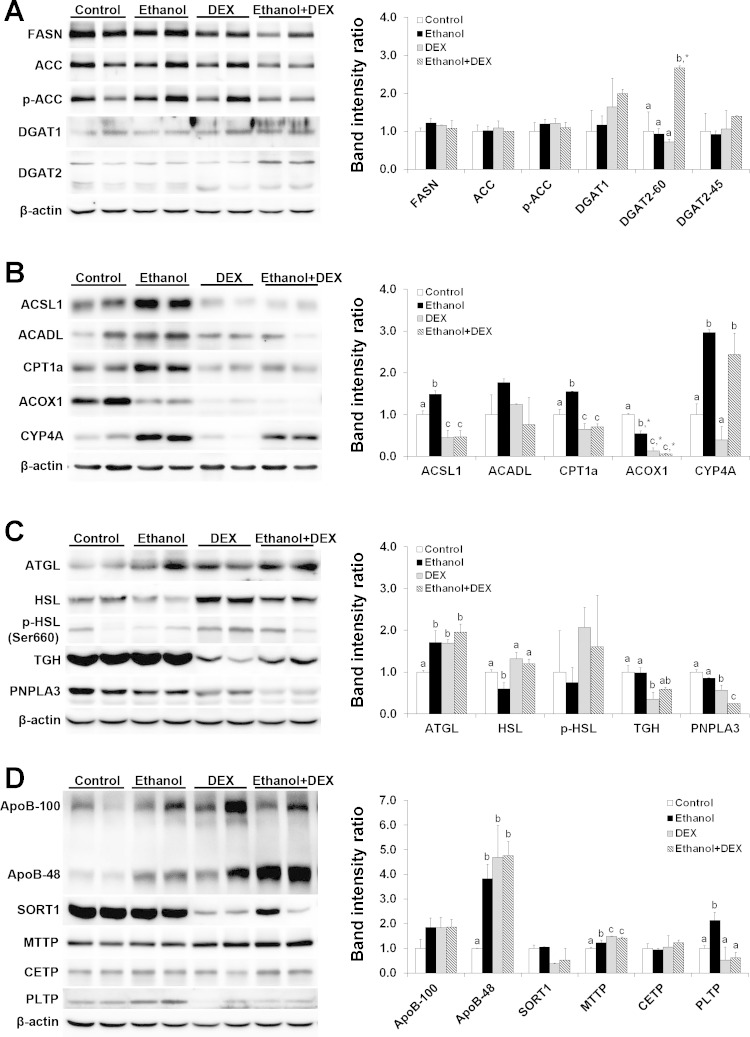

We next verified the protein levels of several key players in hepatic lipid metabolism. Among the five key enzymes related to de novo lipogenesis and triglyceride synthesis (Fig. 6A), only diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2) was significantly affected by ethanol plus dexamethasone treatment (2.7-fold increase). Among the five enzymes related to fatty acid-CoA synthesis and oxidation (Fig. 6B), ethanol ingestion increased the protein levels of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase1 (ACSL1), carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a (CPT1a), and cytochrome P450 4A (CYP4A) but decreased the protein level of acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (ACOX1) compared with the controls. In contrast, dexamethasone alone and dexamethasone plus ethanol significantly reduced the protein levels of ACSL1, CPT1a, and ACOX1 compared with ethanol alone. Among the four enzymes related to triglyceride hydrolysis (Fig. 6C), ethanol ingestion increased the protein level of adipose tissue triglyceride lipase but decreased hormone-sensitive lipase. Compared with ethanol alone, ethanol plus dexamethasone administration reduced the protein level of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 (PNPLA3), a triglyceride hydrolase that is a major risk factor for fatty liver. Among the six proteins and enzymes related to very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) assembly and secretion (Fig. 6D), apolipoprotein B (ApoB) 48 level was dramatically increased (∼4-fold) by ethanol or dexamethasone or both. The protein level of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) was significantly increased by ethanol alone treatment and greatly increased by ethanol plus dexamethasone coadministration. In contrast, phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) was significantly increased only by ingestion of ethanol alone. The protein levels of AopB100, sortilin 1 (SORT1), and cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) were not affected by any treatment.

Fig. 6.

DEX altered the protein expression of critical factors related to lipid metabolism. Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk, and DEX was administered in the liquid diet at 3 mg/kg body wt per day. A: lipogenesis. B: fatty acid oxidation. C: lipolysis. D: VLDL secretion. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 2). Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05. *P < 0.01. FASN, fatty acid synthase; ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; DGAT, diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase; ACSL, long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase; ACADL, long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase; CPT1a, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1a; ACOX1, acyl-CoA oxidase 1; CYP4A, cytochrome P450 4A; ATGL, adipose triglyceride lipase; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; TGH, triacylglycerol hydrolase; PNPLA3, patatin-like phospholipase domain containing protein A 3; ApoB, apolipoprotein B; SORT1, sortillin 1; MTTP, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein; CETP, cholesterol ester transfer protein; PLTP, phospholipid transfer protein.

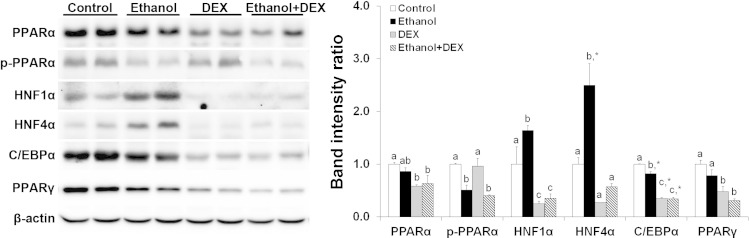

Finally, we verified the protein levels of a number of transcription factors/regulators that regulate hepatic lipid metabolism. PPAR-α protein was not affected by ethanol alone but was significantly decreased by dexamethasone with or without ethanol ingestion. Phosphorylated PPAR-α was decreased by ethanol or ethanol plus dexamethasone ingestion. Both hepatic nuclear factor-1α (HNF-1α) and HNF-4α were significantly increased by ethanol alone but decreased by ethanol plus dexamethasone administration. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBPα) and PPAR-γ, two critical regulators for lipogenesis, were significantly decreased in ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice compared with ethanol alone-fed mice (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

DEX altered the protein levels of various transcription factors. Mice were fed an ethanol liquid diet for 2 wk, and DEX was administered in the liquid diet at 3 mg/kg body wt per day. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Data are expressed as means ± SD (n = 2). Means without a common letter differ at P < 0.05. *P < 0.01. HNF, hepatic nuclear factor; C/EBP-α, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-α.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we showed that excessive and chronic alcohol ingestion was a potent activator of endogenous corticosterone secretion and that increased corticosterone release played a significant modulatory role in ethanol-induced hepatic fat accumulation and liver injury in mice. Increased plasma corticosterone levels were observed in mice after 4 wk, but not 2 wk, of alcohol ingestion. When dexamethasone was administered in the diet, severe liver steatosis was observed at 2-wk alcohol ingestion. However, neither alcohol nor dexamethasone alone in the diet resulted in macrovesicular steatosis after 2 wk of feeding. Using microarray analyses and protein expression validation, we demonstrated that increased glucocorticoids appeared to alter hepatic triglyceride metabolism and particularly suppressed fatty acid β-oxidation, as well as accelerated triglyceride synthesis. Our findings suggest that excessive and prolonged exposure to endogenous glucocorticoids may be involved in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease.

The increased release of glucocorticoids from adrenal glands during ethanol ingestion may be caused by direct or indirect effects of ethanol, or both. Excessive alcohol consumption activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis via acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolic intermediate of ethanol, leading to increased serum ACTH and corticosterone levels (23, 43, 44). Alcohol consumption also decreases food intake, resulting in a certain degree of caloric restriction. Caloric-restricted animals were shown to have increased glucocorticoid concentrations and reduced body weight gain. As a homeostatic response, glucocorticoids increase the catabolism of fatty acids for energy and decrease the synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol (18, 19). In addition to the effects of ethanol, the significant body weight loss in ethanol-fed mice could also be a causative factor for increased corticosterone release, to adapt to the altered energy demands, as the significant body weight loss appeared earlier (after 2 wk of ethanol feeding) than the elevation of corticosterone (after 4 wk of ethanol feeding). Animals employ survival strategies during energy shortage, triggering adaptive mechanisms that alter physiological and biochemical responses, including increased glucocorticoid release (18, 19). Increased endogenous glucocorticoid may also be due to other stressors. Many studies report that some individuals consume alcohol in response to various stresses and believe that drinking helps to reduce the stress. Our findings suggest alcohol abuse would cause more severe damage in the liver under stressful conditions.

ADH1 functions as a primary enzyme in alcohol metabolism in vivo. It has been reported that glucocorticoids upregulate ADH1 gene expression and increase ADH1 enzyme activity in vitro (11, 62). We also found that ADH1 protein levels were significantly increased in vivo in response to dexamethasone and significantly decreased in response to ethanol. Upon exposure to both ethanol and dexamethasone, levels of the ADH1 gene were significantly downregulated, whereas its protein level was increased compared with ethanol alone treatment. CYP2E1 is induced predominantly in the liver by ethanol and may play a more important role than ADH1 in chronic ethanol ingestion (7, 30). The levels of CYP2E1 gene were not changed in ethanol-fed mice, whereas the protein levels were significantly increased. The increased CYP2E1 protein level by ethanol was attenuated by dexamethasone administration. Acetaldehyde accumulation outside the brain prevents further alcohol ingestion. Because there was no significant difference in daily intake of the ethanol-containing diet between ethanol alone-and ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice, we speculated that ethanol metabolism would not be accelerated by dexamethasone administration. Acetaldehyde is also known as one of stimulators in proinflammatory cytokine production (16). In our present study, the levels of proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and IL-6 mRNAs in the liver were not shown a significant difference between ethanol alone- and ethanol plus dexamethasone-treated mice.

PPAR-α is a key transcription factor that regulates lipid metabolism. As a glucocorticoid response gene, PPAR-α is upregulated by dexamethasone in rat primary hepatocytes (25). However, we found that PPAR-α protein was reduced by dexamethasone regardless of ethanol ingestion. Although hepatic PPAR-α protein levels were reduced by long-term ethanol exposure (8 or 16 wk) in our previous studies (21, 56), this inhibitory effect was not found in the present 2-wk ethanol ingestion model. These data suggest the increased glucocorticoid during chronic ethanol ingestion could be a negative regulator of PPAR-α expression. The data of plasma glucose levels and the protein levels of several hepatic rate-limiting enzymes in fatty acid β-oxidation also indicate a link between glucocorticoids and PPAR-α expression. Two weeks of ingestion of ethanol alone did not change mouse plasma corticosterone levels or hepatic PPAR-α protein levels but did reduce blood glucose levels. However, the reduced blood glucose level by ethanol alone was normalized by coadministration of exogenous glucocorticoid, which led to a reduction of hepatic PPAR-α. Therefore, elevated glucocorticoid is likely to play a pathophysiological role in upregulating gluconeogenesis. At the same time, increased glucocorticoid may inhibit fatty acid β-oxidation through PPAR-α inactivation. Reduced fatty acid oxidation by PPAR-α inhibition is one of the important mechanisms underlying ethanol-induced fatty liver (9). Ethanol ingestion for 2 wk increased the levels of proteins related to fatty acid activation (ACSL1), fatty acid β-oxidation in mitochondria (CPT1a), and ω-oxidation in endoplasm reticulum (CYP4A), suggesting that a compensatory response was triggered against the decrease of hepatic fatty acid β-oxidation in the early stage of ethanol ingestion. This compensatory response may explain why 2 wk of ethanol ingestion did not significantly increase hepatic triglyceride levels. However, the protein levels of ACSL1 and CPT1a were reduced by ethanol plus dexamethasone administration. Due to decreased fatty acid β-oxidation by dexamethasone (26), both enzymes thoroughly lost their compensatory ability in response to ethanol ingestion, causing greatly reduced fatty acid β-oxidation through PPAR-α inhibition to lead to fat accumulation in the liver.

Hepatic FFAs derived by either de novo lipogenesis or uptake from the blood are mainly used for fatty acid oxidation or synthesis of triglycerides. As described above, dexamethasone administration to ethanol-fed mice greatly inhibited fatty acid β-oxidation in the liver but did not increase hepatic FFA levels. This is likely due to an increase of DGAT2 protein level in the liver of ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice. DGAT2 catalyzes triglyceride synthesis and facilitates lipid droplet expansion. Glucocorticoid has been shown to increase the activity of DGAT2 (10), which in turn accelerates triglyceride synthesis and decreases FFAs in the liver. However, we found no change of hepatic triglyceride levels between pair-fed control and dexamethasone alone pair-fed mice. Dexamethasone alone administration tended to suppress the release of endogenous corticosterone (data not shown) and actually did not increase the protein levels of several key players of lipogenesis in the mouse liver. We considered this result, which is contrary to prior reports, likely due to the diet limitation of pair feeding as well as the route of dexamethasone administration (given via the liquid diet) in the dexamethasone alone pair-fed mice. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1) is one of PPAR-α downstream targets, which converts saturated fatty acids to monounsaturated fatty acids. SCD1 was the most suppressed gene in the liver of ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice. SCD1 inhibition may ameliorate hepatic steatosis but markedly increased hepatocellular apoptosis and liver injury (28, 38). As PPAR-α-responsive genes, Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 catalyze cholesterol catabolism. Dexamethasone stimulates bile acid synthesis by the induction of CYP7A1 in rat hepatocytes (41, 42). Overexpression of CYP7A1 activates bile acid biosynthesis both in vitro and in vivo to maintain cholesterol homeostasis (27). In the present study, the expression of, not only Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1, but also primary bile acid biosynthesis pathway genes was upregulated. Thus there was no significant difference in hepatic cholesterol levels between ethanol alone- and ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice.

PLTP, a downstream target of PPAR-α, is believed to be one of the main regulators of VLDL export. In previous studies, PLTP deficiency was found to cause a significant impairment in hepatic secretion of VLDL (20), whereas PLTP-overexpressing mice exhibit hepatic VLDL overproduction (29). PLTP expression in PLTP-null mice increased VLDL lipidation in microsomes and VLDL secretion to the plasma (63). The present study demonstrated that hepatic PLTP protein expression was increased by ethanol ingestion but not by dexamethasone, which, at least partially, accounted for hepatic triglyceride levels. Both ApoB and MTTP, which are not regulated by PPAR-α, also play important roles in VLDL export from liver (63). Glucocorticoids promote VLDL secretion through increasing production and reducing the degradation of ApoB (3, 61). The present study showed that hepatic ApoB48 protein was increased by all treatments. However, there was no significant difference in ApoB48 protein levels between ethanol- and ethanol plus dexamethasone-fed mice. These data suggest that VLDL lipidation in addition to ApoB production may critically regulate VLDL export from the liver.

Corticosteroids are used to reduce hepatic inflammation in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH). Although corticosteroids have been reported to improve the survival rate of patients with AH, ∼40% of patients do not respond to corticosteroid treatment and show corticosteroid resistance (31, 35, 39, 40). Until now, it has not been confirmed yet whether endogenous cortisol remains elevated in the corticosteroid-nonresponsive patients. Clinical studies reported that cortisol levels in serum/plasma, urine, or saliva were increased in alcoholics while actively drinking (1, 5, 52, 58). Alcohol-induced pseudo-Cushing's syndrome (AIPCS) was also reviewed by Kirkman and Nelson (24). After abstinence, cortisol level in patients with AIPCS returned to normal. Moreover, a positive relationship between salivary cortisol concentration and alcohol consumption was revealed in healthy men (2). Indeed, hypercortisolism was observed in some but not all human studies (60). The mechanism by which ethanol ingestion influences cortisol secretion and/or metabolism is still unclear. It has been reported that increased cortisol level in patients with ALD was attributed to the deficiency of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, a cortisol metabolism enzyme (52). In the present study, we demonstrated that hypercortisolism would be a contributor in the development of alcoholic liver disease. Our findings suggest that therapeutic corticosteroid resistance could be due to preexisting endogenous cortisol elevation in these patients. Therefore, the determination of the endogenous cortisol level in patients with AH before corticosteroid treatment will be extremely critical in choosing therapeutic options.

Taken together, PPAR-α is a key regulator of lipid metabolism in the coexistence of ethanol and dexamethasone. The effects of dexamethasone administration were associated with inhibition of hepatic PPAR-α protein expression, suggesting a mechanistic link between increased glucocorticoid and PPAR-α inactivation in the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver. PPAR-α is inactivated by coadministration of ethanol and dexamethasone, resulting in suppressed fatty acid β-oxidation due to the reduction of ACSL1, CPT1a, and ACOX1, as well as accelerated triglyceride synthesis due to the increase of DGAT2 in the liver. Our findings suggest that increased glucocorticoids would be a risk factor in the development of alcoholic fatty liver.

GRANTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01AA018844 and R01AA020212.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: Xiuhua Sun and Z.Z. conception and design of research; Xiuhua Sun, X.T., Q.L., Y.Z., W.Z., and Xinguo Sun performed experiments; Xiuhua Sun, W.L., and C.B. analyzed data; Xiuhua Sun interpreted results of experiments; Xiuhua Sun prepared figures; Xiuhua Sun and W.L. drafted manuscript; Xiuhua Sun, Q.L., W.Z., and Z.Z. edited and revised manuscript; Xiuhua Sun, W.L., X.T., Q.L., Y.Z., W.Z., Xinguo Sun, C.B., and Z.Z. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Adinoff B, Ruether K, Krebaum S, Iranmanesh A, Williams MJ. Increased salivary cortisol concentrations during chronic alcohol intoxication in a naturalistic clinical sample of men. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 1420–1427, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badrick E, Bobak M, Britton A, Kirschbaum C, Marmot M, Kumari M. The relationship between alcohol consumption and cortisol secretion in an aging cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 750–757, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagdade JD, Yee E, Albers J, Pykalisto OJ. Glucocorticoids and triglyceride transport: effects on triglyceride secretion rates, lipoprotein lipase, and plasma lipoproteins in the rat. Metabolism 25: 533–542, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beier JI, Arteel GE, McClain CJ. Advances in alcoholic liver disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 13: 56–64, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beresford TP, Arciniegas DB, Alfers J, Clapp L, Martin B, Beresford HF, Du Y, Liu D, Shen D, Davatzikos C, Laudenslager ML. Hypercortisolism in alcohol dependence and its relation to hippocampal volume loss. J Stud Alcohol 67: 861–867, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boé DM, Vandivier RW, Burnham EL, Moss M. Alcohol abuse and pulmonary disease. J Leukoc Biol 86: 1097–1104, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cederbaum AI. Alcohol metabolism. Clin Liver Dis 16: 667–685, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collier SD, Wu WJ, Pruett SB. Ethanol suppresses NK cell activation by polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) in female B6C3F1 mice: role of endogenous corticosterone. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24: 291–299, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabb DW, Galli A, Fischer M, You M. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Alcohol 34: 35–38, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolinsky VW, Douglas DN, Lehner R, Vance DE. Regulation of the enzymes of hepatic microsomal triacylglycerol lipolysis and re-esterification by the glucocorticoid dexamethasone. Biochem J 378: 967–974, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong Y, Poellinger L, Okret S, Höög JO, von Bahr-Lindström H, Jörnvall H, Gustafsson JA. Regulation of gene expression of class I alcohol dehydrogenase by glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 767–771, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Souza El-Guindy NB, de Villiers WJ, Doherty DE. Acute alcohol intake impairs lung inflammation by changing pro- and anti-inflammatory mediator balance. Alcohol 41: 335–345, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis FW. Effect of ethanol on plasma corticosterone levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 153: 121–127, 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emanuele N, Emanuele MA. The endocrine system: alcohol alters critical hormonal balance. Alcohol Health Res World 21: 53–64, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Solà J, Preedy VR, Lang CH, Gonzalez-Reimers E, Arno M, Lin JCI, Wiseman H, Zhou S, Emery PW, Nakahara T, Hashimoto K, Hirano M, Santolaria-Fernàndez F, Gonzàlez-Hernàndez T, Fatjó F, Sacanelia E, Estruch R, Nicolàs JM, Urbano-Màrquez A. Molecular and cellular events in alcohol-induced muscle disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31: 1953–1962, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 141: 1572–1585, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gounarides JS, Korach-André M, Killary K, Argentieri G, Turner O, Laurent D. Effect of dexamethasone on glucose tolerance and fat metabolism in a diet-induced obesity mouse model. Endocrinology 149: 758–766, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gredilla R, Barja G. Minireview: the role of oxidative stress in relation to caloric restriction and longevity. Endocrinology 146: 3713–3717, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gursoy E, Cardounel A, Hu Y, Kalimi M. Biological effects of long-term caloric restriction: adaptation with simultaneous administration of caloric stress plus repeated immobilization stress in rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 226: 97–102, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang XC, Qin S, Qiao C, Kawano K, Lin M, Skold A, Xiao X, Tall AR. Apolipoprotein B secretion and atherosclerosis are decreased in mice with phospholipid-transfer protein deficiency. Nat Med 7: 847–852, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang X, Zhong W, Liu J, Song Z, McClain CJ, Kang YJ, Zhou Z. Zinc supplementation reverses alcohol-induced steatosis in mice through reactivating hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Hepatology 50: 1241–1250, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keshavarzian A, Farhadi A, Forsyth CB, Rangan J, Jakate S, Shaikh M, Banan A, Fields JZ. Evidence that chronic alcohol exposure promotes intestinal oxidative stress, intestinal hyperpermeability and endotoxemia prior to development of alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. J Hepatol 50: 538–547, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinoshita H, Jessop DS, Finn DP, Coventry TL, Roberts DJ, Ameno K, Jiri I, Harbuz MS. Acetaldehyde, a metabolite of ethanol, activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the rat. Alcohol Alcohol 36: 59–64, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirkman S, Nelson DH. Alcohol-induced pseudo-Cushing's disease: a study of prevalence with review of the literature. Metabolism 37: 390–394, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemberger T, Staels B, Saladin R, Desvergne B, Auwerx J, Wahli W. Regulation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene by glucocorticoids. J Biol Chem 269: 24527–24530, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lettéron P, Brahimi-Bourouina N, Robin MA, Moreau A, Feldmann G, Pessayre D. Glucocorticoids inhibit mitochondrial matrix acyl-CoA dehydrogenases and fatty acid beta-oxidation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 272: G1141–G1150, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li T, Matozel M, Boehme S, Kong B, Nilsson LM, Guo G, Ellis E, Chiang JY. Overexpression of cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase promotes hepatic bile acid synthesis and secretion and maintains cholesterol homeostasis. Hepatology 53: 996–1006, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li ZZ, Berk M, McIntyre TM, Feldstein AE. Hepatic lipid partitioning and liver damage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase. J Biol Chem 284: 5637–5644, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lie J, de Crom R, van Gent T, van Haperen R, Scheek L, Lankhuizen I, van Tol A. Elevation of plasma phospholipid transfer protein in transgenic mice increases VLDL secretion. J Lipid Res 43: 1875–1880, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieber CS. Alcoholic fatty liver: its pathogenesis and mechanism of progression to inflammation and fibrosis. Alcohol 34: 9–19, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 360: 2758–2769, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo W, Friedman MS, Shedden K, Hankenson KD, Woolf PJ. GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 161, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo W, Brouwer C. Pathview: an R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics 29: 1830–1831, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macfarlane DP, Forbes S, Walker BR. Glucocorticoids and fatty acid metabolism in humans: fuelling fat redistribution in the metabolic syndrome. J Endocrinol 197: 189–204, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCullough AJ, O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S. Diagnosis and management of alcoholic liver disease. J Dig Dis 12: 257–262, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonough AK, Curtis JR, Saag KG. The epidemiology of glucocorticoid-associated adverse events. Curr Opin Rheumatol 20: 131–137, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meadows GG, Blank SE, Yirmiya R, Taylor AN. Modulation of natural killer cell activity by alcohol. In: Alcohol, Immunity, and Cancer, edited by Yirmiya R, Taylor AN. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyazaki M, Dobrzyn A, Sampath H, Lee SH, Man WC, Chu K, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Ntambi JM. Reduced adiposity and liver steatosis by stearoyl-CoA desaturase deficiency are independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. J Biol Chem 279: 35017–35024, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Alcoholic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 105: 14–32, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 51: 307–328, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pandak WM, Schwarz C, Hylemon PB, Mallonee D, Valerie K, Heuman DM, Fisher RA, Redford K, Vlahcevic ZR. Effects of CYP7A1 overexpression on cholesterol and bile acid homeostasis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 281: G878–G889, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Princen HM, Meijer P, Hofstee B. Dexamethasone regulates bile acid synthesis in monolayer cultures of rat hepatocytes by induction of cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase. Biochem J 262: 341–348, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pruett SB, Collier SD, Wu WJ. Ethanol-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in a mouse model for binge drinking: role of Ro15–4513-sensitive gamma aminobutyric acid receptors, tolerance, and relevance to humans. Life Sci 63: 1137–1146, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivier C. Alcohol stimulates ACTH secretion in the rat: mechanisms of action and interactions with other stimuli. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 20: 240–254, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rivier C, Bruhn T, Vale W. Effect of ethanol on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the rat: role of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 229: 127–131, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosol TJ, Yarrington JT, Latendresse J, Capen CC. Adrenal gland: structure, function, and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicol Pathol 29: 41–48, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaaf MJ, Cidlowski JA. Molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid action and resistance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 83: 37–48, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schacke H, Docke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther 96: 23–43, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoneveld OJ, Gaemers IC, Lamers WH. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1680: 114–128, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sebastian BM, Roychowdhury S, Tang H, Hillian AD, Feldstein AE, Stahl GL, Takahashi K, Nagy LE. Identification of a cytochrome P4502E1/Bid/C1q-dependent axis mediating inflammation in adipose tissue after chronic ethanol feeding to mice. J Biol Chem 286: 35989–35997, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sisson JH. Alcohol and airways function in health and disease. Alcohol 41: 293–307, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stewart PM, Burra P, Shackleton CH, Sheppard MC, Elias E. 11 Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency and glucocorticoid status in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic chronic liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 76: 748–751, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun X, Tang Y, Tan X, Li Q, Zhong W, Sun X, Jia W, McClain CJ, Zhou Z. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ by rosiglitazone improves lipid homeostasis at the adipose tissue-liver axis in ethanol-fed mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G548–G557, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szabo G, Mandrekar P. A recent perspective on alcohol, immunity, and host defense. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33: 220–232, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabakoff B, Jafee RC, Ritzmann RF. Corticosterone concentrations in mice during ethanol drinking and withdrawal. J Pharm Pharmacol 30: 371–374, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan X, Sun X, Li Q, Zhao Y, Zhong W, Sun X, Jia W, McClain CJ, Zhou Z. Leptin deficiency contributes to the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Am J Pathol 181: 1279–1286, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang H, Sebastian BM, Axhemi A, Chen X, Hillian AD, Jacobsen DW, Nagy LE. Ethanol-induced oxidative stress via the CYP2E1 pathway disrupts adiponectin secretion from adipocytes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36: 214–222, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thayer JF, Hall M, Sollers JJ, 3rd, Fischer JE. Alcohol use, urinary cortisol, and heart rate variability in apparently healthy men: evidence for impaired inhibitory control of the HPA axis in heavy drinkers. Int J Psychophysiol 59: 244–250, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tiwari S, Siddiqi SA. Intracellular trafficking and secretion of VLDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1079–1086, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wand GS, Dobs AS. Alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in actively drinking alcoholics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 72: 1290–1295, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang CN, McLeod RS, Yao Z, Brindley DN. Effects of dexamethasone on the synthesis, degradation, and secretion of apolipoprotein B in cultured rat hepatocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 15: 1481–1491, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolfla CE, Ross RA, Crabb DW. Induction of alcohol dehydrogenase activity and mRNA in hepatoma cells by dexamethasone. Arch Biochem Biophys 263: 69–76, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yazdanyar A, Jiang XC. Liver phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) expression with a PLTP-null background promotes very low-density lipoprotein production in mice. Hepatology 56: 576–584, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.