Abstract

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) diminishes vasodilatory and neuroprotective effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids by hydrolyzing them to inactive dihydroxy metabolites. The primary goals of this study were to investigate the effects of acute sEH inhibition by trans-4-[4-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-cyclohexyloxy]-benzoic acid (t-AUCB) on infarct volume, functional outcome, and changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) in a rat model of ischemic stroke. Focal cerebral ischemia was induced in rats for 90 min followed by reperfusion. At the end of 24 h after reperfusion rats were euthanized for infarct volume assessment by triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining. Brain cortical sEH activity was assessed by ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Functional outcome at 24 and 48 h after reperfusion was evaluated by arm flexion and sticky-tape tests. Changes in CBF were assessed by arterial spin-labeled-MRI at baseline, during ischemia, and at 180 min after reperfusion. Neuroprotective effects of t-AUCB were evaluated in primary rat neuronal cultures by Cytotox-Flour kit and propidium iodide staining. t-AUCB significantly reduced cortical infarct volume by 35% (14.5 ± 2.7% vs. 41.5 ± 4.5%), elevated cumulative epoxyeicosatrienoic acids-to-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids ratio in brain cortex by twofold (4.40 ± 1.89 vs. 1.97 ± 0.85), and improved functional outcome in arm-flexion test (day 1: 3.28 ± 0.5 s vs. 7.50 ± 0.9 s; day 2: 1.71 ± 0.4 s vs. 5.28 ± 0.5 s) when compared with that of the vehicle-treated group. t-AUCB significantly reduced neuronal cell death in a dose-dependent manner (vehicle: 70.9 ± 7.1% vs. t-AUCB0.1μM: 58 ± 5.11% vs. t-AUCB0.5μM: 39.9 ± 5.8%). These findings suggest that t-AUCB may exert its neuroprotective effects by affecting multiple components of neurovascular unit including neurons, astrocytes, and microvascular flow.

Keywords: arachidonic acid, cerebral blood flow, cytochrome P-450, ischemic stroke, middle cerebral artery occlusion

one mechanism contributing to neuronal death after cerebral ischemia is the release of bioactive free fatty acids (FFA) early after injury. These FFAs are liberated from plasma membrane phospholipids mainly by phospholipase A2 (PLA2) (29). Accumulation of the saturated and polyunsaturated FFA (PUFA) may indicate regional lipid membrane damage, which further leads to progressive infarction after cerebral ischemia (1, 5, 6, 15). The accumulation of FFAs and the subsequent synthesis of oxygenated metabolites of these FFAs contribute to functional impairment after cerebral ischemia. It has been shown that the accumulation of FFAs after cerebral ischemia correlates locally with the severity of the insult (4). The cascade of events leading to ischemic injury-associated secondary brain damage due to accumulation of FFAs is mediated by direct and indirect mechanisms. Direct mechanisms include disruption of cellular energy metabolism, induction of blood-brain barrier breakdown, and edema formation (9, 30, 38). Indirect mechanisms include generation of active oxygenated metabolites of liberated FFA that affect cerebral blood flow (CBF) and vascular tone (11, 27).

Arachidonic acid (C20:4, ω-6; AA) is one of the PUFA released from the phospholipids of cell membranes into the cytosol in response to stimuli such as ischemia (8). Free AA is metabolized to biologically active products by cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase, and cytochrome P-450 (CYP450) pathways (25). Of the three pathways, the CYP450 pathway metabolizes AA into linear metabolites by incorporating one oxygen atom to form HETEs (hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs). CYP4A and CYP4F enzymes form terminal and various mid-chain HETEs. CYP2C and CYP2J enzymes form four different regio-isomers by epoxidation of the unsaturated double bonds at the 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15- carbons, thereby forming four epoxide isomers. EETs are predominantly metabolized in vivo to less active dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs; 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-DHET) by soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) enzyme (10, 34).

Unlike most of ω-6 FFA metabolites, which are pro-inflammatory mediators of ischemic damage, EETs have been shown to protect cells during ischemic insult. EETs act as important cellular lipid mediators in the cardiovascular, renal, and nervous systems (16, 19). In cerebral vasculature, EETs play an important role in CBF regulation (2) and neurovascular coupling (21). EETs have been implicated as mediators of vascular tone and inflammatory processes (35) and are also referred to as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors because of their ability to dilate arteries (7). Thus EETs have become an attractive target for the treatment of cerebrovascular complications such as cerebral ischemia.

One method of increasing EETs levels in the brain is by inhibiting their primary route of degradation to less active dihydroxy metabolites by sEH (31). sEH inhibitors have been shown to be neuroprotective; however, no studies have evaluated whether single dose acute administration of sEH inhibitors can improve neurofunctional outcomes after ischemic stroke. These data are essential to add to the growing data to establish whether sEH inhibition meets the STAIR criteria for further clinical development (14). Therefore, the primary goals of this study were to evaluate the effect of acute sEH inhibition by t-AUCB on infarct volume, functional outcome, and changes in CBF using a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model in rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals and experimental design.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g; Hilltop Laboratory Animals, Scottsdale, PA) were maintained on a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle and were given food and water ad libitum. The rats were randomly assigned to either vehicle [lyophilized hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD), 15%] or treatment (lyophilized t-AUCB in HPβCD, 0.5 mg) groups. MCAO was performed on all rats. All HPβCD lyophilized complexes (vehicle or t-AUCB) were reconstituted in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.2, and filtered before administration. Treatment group rats received a single t-AUCB 0.9 mg/Kg bolus dose via the femoral vein at the time of MCAO. Five experiments were performed: 1) effect of t-AUCB on cerebral infarct volume after MCAO (n = 9/group); 2) t-AUCB inhibitory potential on brain cortical sEH activity (n = 6/group); 3) acute t-AUCB effect on short-term behavioral outcome after MCAO (n = 9/group); 4) changes in CBF during and after MCAO with t-AUCB treatment were determined with arterial spin-labeled-MRI (ASL-MRI; n = 7/group); and 5) effect of t-AUCB on primary neuronal cultures after hypoxic injury (n = 6 wells/group). The surgeon and individuals involved in all above experiments were blinded to all treatment groups.

MCAO in rats.

Rats received MCAO for 90 min followed by reperfusion as described previously (32). Briefly, rats were anesthetized via nose cone with 1% to 2% isoflurane, 50/50 N2O/O2 throughout surgery. The left common carotid artery was exposed, and the external common carotid artery was isolated and ligated using 5–0 silk (Ethicon). MCAO was achieved by inserting a 5-0 nylon suture (with tip coated with silicon ∼280 μm diameter) into the internal carotid artery a distance of 16–19 mm from the bifurcation of the common carotid artery and internal carotid artery. The wound was closed, and the animals were allowed to recover with the suture in place. After 90 min, the rats were re-anesthetized and the suture removed, initiating reperfusion. Sham surgeries were performed in the same manner as MCAO surgeries but without insertion of suture. Throughout the surgical procedure core temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C using a thermo regulated heating pad.

Infarct volume determination.

Rats (n = 9/group) were euthanized at 24 h after reperfusion, and infarct volume was assessed by staining with 2,3,5-triphenyl-tetrazolium chloride (TTC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 2% in phosphate-buffered saline). Brains were placed in a rat brain matrix (ASI Instruments, Warren, MI) and were sliced into 1-mm sections. The sections were immersed in the TTC for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were transferred to formalin and photographed. Infarct volume was measured using image analysis (MCID; St Catharines, Ontario, Canada). To minimize the effect of edema on the quantification of infarct size, the method of Swanson et al. (36) was used. The percent infarct volume was calculated by dividing infarct volume by contralateral hemisphere volume.

Tissue extraction and chromatographic analysis of AA metabolites.

Concentrations of various metabolites including HETEs (12-, 15-, and 20-HETE), EETs (8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET), DHETs (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-DHET), PGs (6-keto-PGF1α, 11β-PGF2α, PGE2, PGD2, PGJ2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGD2, 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2, PGF1α, PGF2α, PGA2), and TXB (11-dehydro-TXB2) were determined from brain cortical tissues of vehicle and t-AUCB (0.9 mg/kg iv; n = 6/group)-treated rats that underwent MCAO surgery using solid phase extraction as described previously with slight modifications (26, 28). Briefly, tissue samples were homogenized in deionized water containing 0.113 mM butylated hydroxytoluene and centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was removed and spiked with 12.5 μl (containing 12.5 ng) of 20-HETE-d6 (for all HETEs, EETs, and DHETs), PGD2-d4, 15-deoxy-PGJ2-d4, 6-keto-PGF1-d4, 11β-PGF2-d4, PGF1-d9, 11-deoxy-TxB2-d4, PGE2-d4, and PGF2-d4 as internal standards. The spiked supernatant samples were loaded onto Oasis hydrophilic-lipophilic balanced (30 mg) solid phase extraction cartridges (Waters, Milford, MA) that were conditioned and equilibrated with 1 ml of methanol and 1 ml of water, respectively. Columns were washed with three 1-ml volumes of 5% methanol and were eluted with 100% methanol. Extracts were spiked with 15 μl of 1% acetic acid in methanol, dried under nitrogen gas at 37°C, and reconstituted in 125 μl of 80:20 methanol/deionized water for chromatographic analysis as described previously (26).

Briefly HETEs, EETs, and DHETs were separated on a ultra performance liquid chromatography BEH C-18 column 1.7 μm (2.1 × 100 mm), and PGs were separated on a ultra performance liquid chromatography BEH C-18, 1.7 μm (2.1 × 150 mm) reverse-phased column (Waters, Milford, MA) protected by a guard column (2.1 mm × 5 mm; Waters) of the same packing material. Column temperature was maintained at 55°C. Mobile phases consisted of 0.005% acetic acid, 5% acetonitrile in deionized water (A), and 0.005% acetic acid in acetonitrile (B). HETEs, EETs, and DHETs were separated by delivering mobile phase at 0.5 ml/min at an initial mixture of 65:35 A and B, respectively. Mobile phase B was increased from 35% to 70% in a linear gradient over 4 min, and again increased to 95% over 0.5 min where it remained for 0.3 min. This was followed by a linear return to initial conditions over 0.1 min with a 1.5 min pre-equilibration period before the next sample run. A slightly different gradient program was used for PGs separation where the mobile phase was delivered at 0.4 ml/min at an initial mixture of 65:35 A and B. Mobile phase B was maintained at 35% for 7.5 min and then increased to 98% in a linear gradient over 1.5 min, where it remained for 0.2 min. This was followed by a linear return to initial conditions over 0.1 min with a 2.7 min pre-equilibration period before the next sample run. Total run time per sample was 6.4 min for HETEs, EETs, and DHETs and 12 min for all PGs. All injection volumes were 7.5 μl.

Mass spectrometric analysis of analyte formation was performed using a TSQ Quantum Ultra (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) triple quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled with heated electrospray ionization operated in negative selective reaction monitoring mode with unit resolutions at both Q1 and Q3 set at 0.70 full width at half maximum. Quantitation by selective reaction monitoring analysis on HETEs, EETs, DHETs, and PGs was performed by monitoring their m/z transitions. Scan time was set at 0.01 s, and collision gas pressure was set at 1.3 mTorr. Analytical data was acquired and analyzed using Xcalibur software version 2.0.6 (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA).

Functional outcome assessment.

Functional outcome experiments were aimed at evaluating motor activity (primary motor cortex) and somatosensory activity of rats that underwent MCAO surgery. Behavioral deficits (functional outcome evaluation) in rats (n = 9/group) were examined at 24 and 48 h after reperfusion. A simple neurological scoring system was used to assess neurological damage following MCAO surgery as follows: 0 = no neurological deficit; 1 = failure to extend left forepaw fully and torso turning to ipsilateral side when held by tail (a mild focal neurologic deficit); 2 = circling to the effected side (a moderate focal neurologic deficit); 3 = unable to bear weight on the effected side (a severe focal deficit); 4 = no spontaneous locomotor activity. Behavioral deficits were determined using the arm flexion and sticky tape test as described previously (3). The arm flexure test was conducted once daily by lifting rats by their tails so that their ventral surface was exposed for observation. The cumulative duration of asymmetrical arm flexure during a 10-s period after tail lifting was recorded using a stop watch. In the tape test, self-adhesive labels (1-cm-diameter circles) were placed on each forepaw to assess the time required for the rat to touch and remove each label. In addition, the order (contralateral vs. ipsilateral) of removal was also used to determine ipsilateral asymmetry. Preference for a given wrist was accounted for by affixing larger labels to the wrist less preferred and correspondingly smaller labels to the other wrist. The larger the ratio between surface of ipsilateral versus contralateral patches (from 1:1 to 1/8:15/8), the more extensive the damage (scored on a scale from 1 to 7 in the increasing order of severity of damage). One trial per day was conducted at 24 and 48 h after reperfusion.

Cerebral blood flow assessment using ASL-MRI imaging.

CBF measurements were assessed by arterial spin-labeled (ASL)-MRI. Rats (n = 7/group) underwent femoral artery catheterization and were placed in a prone position on the cradle. MRI was performed using a 4.7-Tesla, 40-cm bore Bruker BioSpec AVI system (Billerica), equipped with a 12-cm shielded gradient insert. A 72-mm volume coil with 2.5 cm actively decoupled brain surface coil was used for imaging. Continuous ASL was used to quantify CBF (12, 39). A single shot SE-EPI sequence was used with a TR = 2 s, 64 × 64 matrix, FOV = 2.3 cm, 2-s labeling pulse. The labeling pulse for the inversion plane was positioned ± 2 cm from the perfusion detection plane. For each experiment, a map of the spin-lattice relaxation time of tissue water (T1obs) was generated from a series of spin-echo images with variable TR (FOV = 2.3 cm, 4 averages, 64 × 64 matrix) (17). CBF was assessed at three time points: at baseline, 70 min (during the occlusion period), and at 270 min (3 h after reperfusion). Blood gases were sampled at each time point and analyzed (Radiometer, Westlake, OH). For the duration of the experiment mean arterial blood pressure and EKG were continuously monitored. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37°C using a warm air system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY).

The effect of t-AUCB on primary neuronal cultures after hypoxic injury.

Rat primary cortical neurons were prepared as described previously (23). Briefly, cortical primary neuronal cultures were prepared from E17 fetal rats. Brains were removed and cortices dissected. Brain cortical tissue was freed of meninges and trypsinized for 30 min in 0.25% trypsin in DMEM. After being centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 min, the supernatant was removed and the tissue was triturated in culture medium to produce a single-cell suspension. The cells were then plated at a density of 6 × 104 cells/well. The medium was replaced the following day and every 3 days thereafter with Neurobasal A medium (Invitrogen). The cultures were used for hypoxia experiments after 11 days. On the 12th day, the cells were either pretreated for 1 h with vehicle (neurobasal medium) or t-AUCB diluted in neurobasal medium at a final concentration of 0.1 and 0.5 μM. After pretreatment, the culture plates were placed into a hypoxic glove box (Coy Laboratories, Grass Lake, MI) flushed with argon for a period of 3 h, resulting in ∼50% cell death after 24 h of reperfusion under normal incubation conditions. Staurosporine (20 μM, a 100% cell death internal standard) and MK801 (1 μM, a 100% cytoprotective internal standard) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cytotoxicity was evaluated using a CytoTox-Fluor kit (Promega, Madison, WI) assay and propidium iodide (PI) staining (Molecular Probes) in two different experiments. At the end of the 24-h incubation period, cells were imaged under a fluorescent microscope for Hoechst (blue) and PI (red) staining and counted. Cell death in all treatment groups was normalized to that of the staurosporine-treated group.

Statistical analysis.

Significant differences between treatment groups in experiments measuring infarct volume and brain sEH activity were assessed by Student's t-test, and for in vitro neuronal culture experiments one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test was used. Significant differences for ASL-MRI blood flow measurements and functional outcome assessments were determined via two-way ANOVA analysis. A *P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of t-AUCB on infarct volume after MCAO.

The effect of acute t-AUCB pretreatment on infarct volume after MCAO was evaluated and compared against vehicle. Figure 1A depicts representative rat brain sections stained with TTC. A significant reduction in percent infarct volume was observed in t-AUCB as compared with vehicle-treated (14.5 ± 2.7% vs. 41.5 ± 4.5%; ***P < 0.001) rats (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The effect of acute trans-4-[4-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-cyclohexyloxy]-benzoic acid (t-AUCB) treatment on brain infarct volume after temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rats (n = 9). A: representative rat brain sections stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride following vehicle (HPβCD) or t-AUCB. B: percent infarct volume in rats treated with vehicle (HPβCD) or t-AUCB. Percent infarct volume was calculated by dividing infarct volume by contralateral hemisphere volume. Rats were euthanized 24 h after MCAO, and brain sections were obtained for infarct volume determination. Data represented as means ± SD. ***Significant values for P < 0.01.

Effect of t-AUCB administration on brain sEH activity after MCAO.

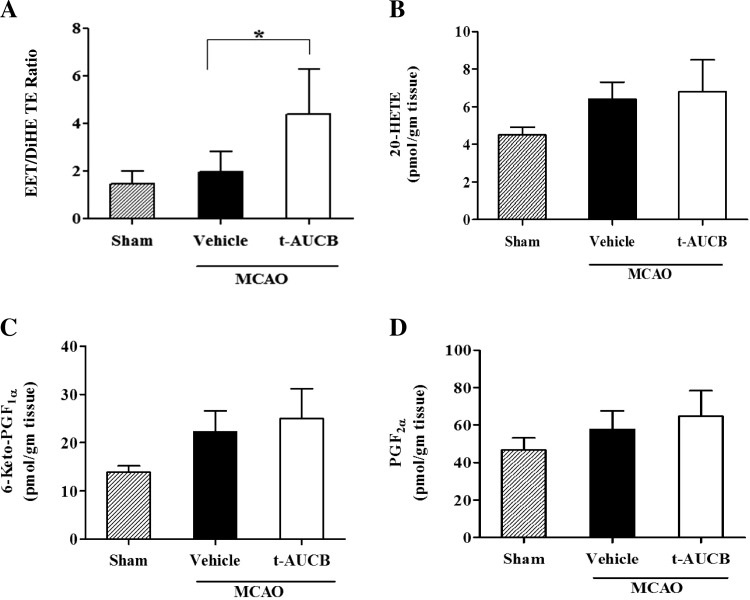

The effect of acute sEH inhibition by t-AUCB in brain cortex after MCAO was assessed by measuring concentrations of various HETEs, EETs, and DHETs as well as various PGs to verify the specificity of t-AUCB inhibition. A significant increase in the ratio of cumulative EETs (11,12- and 14,15-EET) to DHETs (11,12- and 14,15-DHET) was observed in t-AUCB as compared with vehicle-treated (4.40 ± 1.89 vs. 1.97 ± 0.85; *P < 0.05) rats (Fig. 2A). No significant differences were observed in the concentrations of representative metabolites from the HETE and PG family such as 20-HETE (Fig. 2B: vehicle: 6.39 ± 0.92 vs. t-AUCB: 6.80 ± 1.7 pmol/gm tissue; P = 0.62); 6-keto-PGF1α, a metabolite of prostacyclin (Fig. 2C: vehicle: 22.26 ± 4.35 vs. t-AUCB: 24.98 ± 6.21 pmol/gm tissue; P = 0.41); and PGF2α (Fig. 2D: vehicle: 57.73 ± 9.92 vs. t-AUCB: 64.68 ± 13.73 pmol/gm tissue; P = 0.35) in the cortex of t-AUCB and vehicle-treated rats. Control values of these metabolites (without stroke) were also depicted in respective figures. Representative LC/MS chromatograms depicting the levels of EET and 20-HETE before and after treatment with t-AUCB are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2.

The effect of acute t-AUCB treatment on brain cortical soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) activity after temporary MCAO in rats (n = 6). Rats treated with t-AUCB showed a significant increase in the ratio of cumulative epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs)/dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs) (11,12- and 14,15- EET/DHET) (A) but no significant changes in 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETE; B), 6-Keto-PGF1α (metabolite of PGI2; C), and PGF2α (D) when compared with the vehicle-treated group. Brain cortices were collected at 6 h after t-AUCB dosing. Data represented as means ± SD. *Significant values for P < 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Representative LC/MS chromatograms of rat brain cortical sample showing EETs and 20-HETE before (A) and (B) treatment with t-AUCB.

Effect of t-AUCB treatment on functional outcome after MCAO.

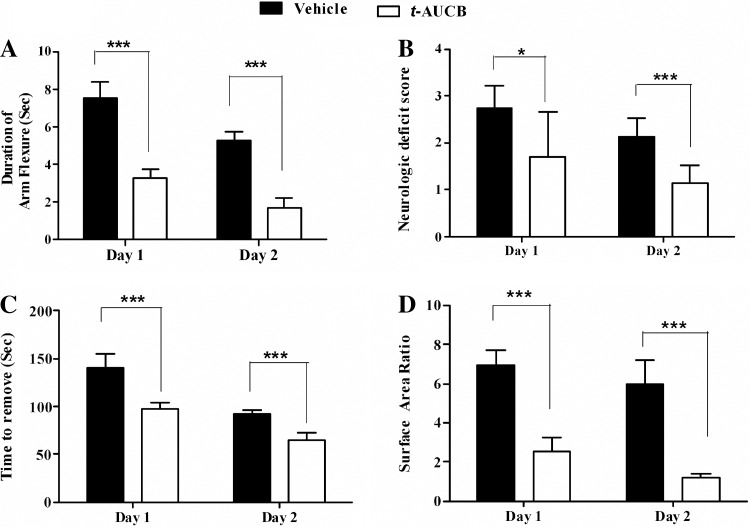

The effect of t-AUCB pretreatment on short-term behavioral deficits after MCAO was evaluated in arm flexion and sticky tape behavioral tests. Rats receiving t-AUCB treatment showed significantly improved outcome in the arm flexure test on days 1 and 2 as compared with the vehicle-treated group (day 1: 3.28 ± 0.5 s vs. 7.50 ± 0.9 s, ***P < 0.001; day 2: 1.71 ± 0.4 s vs. 5.28 ± 0.5 s, ***P < 0.001; Fig. 4A). Similarly, t-AUCB treatment significantly lowered neurological deficit scores on days 1 and 2 compared with the vehicle-treated group (day 1: 1.71 ± 0.9 vs. 2.75 ± 0.4, *P < 0.05; day 2: 1.14 ± 0.3 vs. 2.14 ± 0.3, ***P < 0.001; Fig. 4B). Sticky tape tests also revealed a significant impact of t-AUCB on days 1 and 2 compared with the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 4, C and D). Time to remove (in seconds) sticky tape from the contralateral arm was 140.37 ± 15 s vs. 92.8 ± 3.5 s on days 1 and 2, respectively, in the vehicle group, which was significantly reduced in the t-AUCB group on both days 1 and 2 (98.15 ± 6 s and 64.6 ± 8 s,***P < 0.001). Tape surface area ratio of contralateral to ipsilateral arm in the vehicle group was 6.96 ± 0.77 vs. 5.97 ± 1.2 on days 1 and 2, respectively. This was significantly reduced with t-AUCB treatment on both days (2.53 ± 0.6 vs 1.19 ± 0.2, ***P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

The effect of acute t-AUCB on functional outcome in a rat temporary MCAO model (n = 9). Rats treated with t-AUCB showed significant improvement in arm flexure (A), neurological deficit score (B), time to remove tape (C), and tape surface area ratio (D) compared with vehicle-treated group on both days 1 and 2. Data represented as means ± SD. *Significant values for P < 0.05; ***significant values for for P < 0.001.

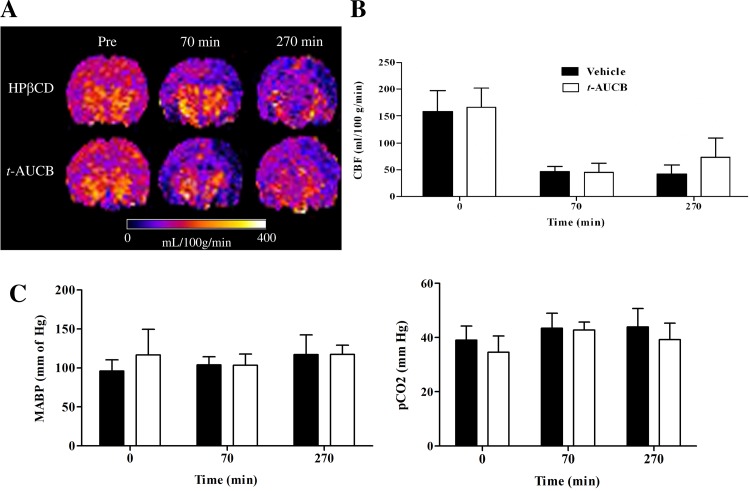

Effect of t-AUCB treatment on cerebral blood flow changes after MCAO.

The effect of t-AUCB treatment on changes in CBF during and after ischemic injury was assessed with ASL MRI. Representative brain perfusion maps of rats treated with t-AUCB or vehicle at three different time points are shown in Fig. 5A. There is mild to moderate improvement in perfusion around the infarcted tissue during the post-ischemic hypoperfusion period (270-min MRI scan) in t-AUCB-treated rats. CBF values calculated from perfusion and T1obs maps revealed no differences in the CBF values between the two groups at baseline and during ischemic injury (Fig. 5B). However, a nonsignificant trend toward increased CBF was seen during the post-ischemic hypoperfusion period (180 min after reperfusion) in t-AUCB-treated rats compared with vehicle control (Fig. 4B; t-AUCB: 73.3 ± 35 vs. vehicle: 42.2 ± 17 ml/100 g/min; P = 0.079). No statistically significant differences between physiological variables such as mean arterial blood pressure and pCO2 were observed between the two treatment groups (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the cerebral cortex ipsilateral to infarct of vehicle and t-AUCB-treated rats (n = 7). A: representative brain CBF maps of rats treated with vehicle or t-AUCB before MCAO (pre), during MCAO (70 min), and after post-ischemic reperfusion (270 min). Dark blue area on right cerebral cortex signifies formation of infarct. B: CBF values (reported as ml/100 g tissue/min) in the cortex ipsilateral to infarct. C: physiological parameters [mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) and blood pCO2]. Data represented as means ± SD.

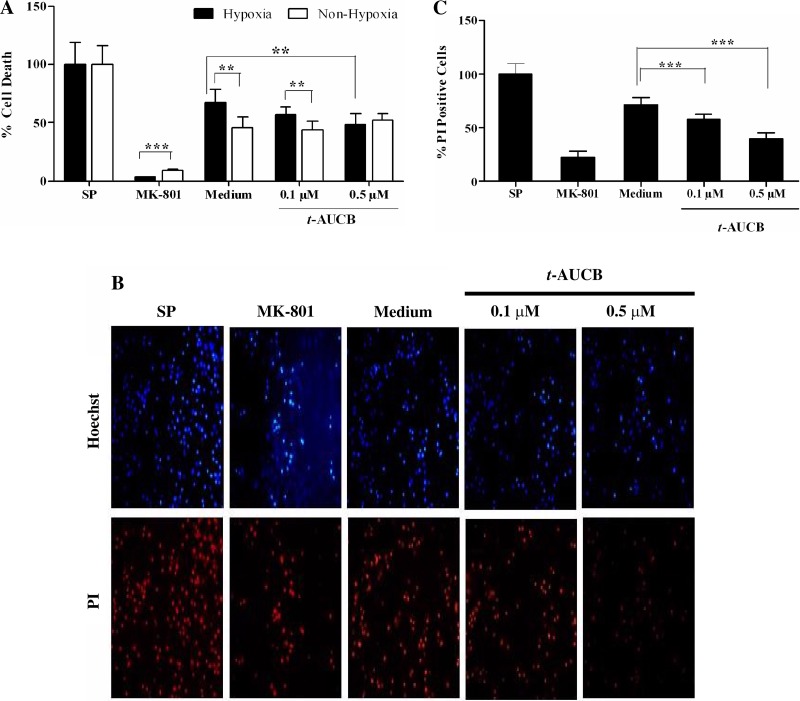

Effect of t-AUCB on cytotoxicity of in vitro neuronal cultures under hypoxic conditions.

The effect of t-AUCB on cytotoxicity of rat primary cortical neuronal culture was assessed by treating neurons with 0.1 and 0.5 μM t-AUCB followed by hypoxic injury. Pretreatment before hypoxic injury resulted in a slight nonsignificant reduction in cell death at 0.1 μM (cell death: vehicle: 67 ± 11.6 vs. t-AUCB: 56.91 ± 7%; P = 0.057) and significant reduction at 0.5 μM (cell death: vehicle: 67 ± 11.6 vs. t-AUCB: 48.5 ± 9.5%; **P < 0.01) compared with their respective vehicle-treated groups as assessed by the CytoTox-Fluor kit assay (Fig. 6A). Under nonhypoxic conditions of incubation t-AUCB did not alter neuronal survival compared with vehicle-treated group (cell death: vehicle: 45.56 ± 9.4%; t-AUCB0.1μM: 44.09 ± 7.5%; t-AUCB0.5μM: 52.04 ± 6.1%; P = 0.124) when tested at the same concentration range (Fig. 6A). In another experiment, neurons treated with t-AUCB at 0.1 and 0.5 μM before hypoxic injury were imaged under a fluorescent microscope for Hoechst (blue) and PI (red) staining (Fig. 6B). t-AUCB pretreatment before hypoxic injury resulted in significant reduction in cell death in a dose-dependent manner (percent PI-positive cells: vehicle: 70.9 ± 7.1 vs. t-AUCB0.1μM: 58 ± 5.11; vs. t-AUCB0.5μM: 39.9 ± 5.8; ***P < 0.001) compared with the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

The effect of t-AUCB on cytotoxicity of primary rat cortical neuronal cultures. Cytotoxicity was assessed by using a Cytotox-Flour kit and propidium iodide (PI) staining. Cytotoxicity was represented as percent cell death normalized to positive control staurosporine (SP). A: percent cell death with t-AUCB or vehicle treatment under hypoxic and nonhypoxic conditions. B: representative images of rat primary cortical neuronal cultures imaged under fluorescence microscope after Hoechst (blue) and PI (red) staining. C: cytotoxicity assessment after hypoxic injury by PI staining. Staurosporine and MK-801 were used as positive and negative controls. Data represented as means ± SD. **Significant values for P < 0.01; ***significant values for P < 0.001, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the neuroprotective effects of acute sEH inhibition with a single low-dose t-AUCB (0.9 mg/kg iv) in focal ischemic stroke and the factors contributing to the neuroprotection. Specifically, we have established causative relationship between acute sEH inhibition, EETs concentrations, and neuroprotection. Furthermore, this study is the first to report the impact of acute sEH inhibition on behavioral performance using comprehensive behavioral tests evaluating motor and somatosensory activity. The major findings of this study are that a single low-dose administration of t-AUCB 1) significantly decreases infarct volume and elevates brain cortical EETs concentrations, 2) does not significantly alter CBF as determined by ASL-MRI, and 3) significantly increases neuronal survival under hypoxic conditions. Collectively, these data suggest that acute inhibition of sEH by t-AUCB offers neuroprotection primarily through a direct cytoprotective effect on neurons with a minor contribution from alterations in CBF.

Our finding of significant reduction in infarct volume after MCAO is consistent with the previous data reported using urea-based derivative 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-dodecanoic acid butyl ester (AUDA-nBE) in a mouse (10 mg/kg ip) (13, 18, 41) and rat (2 mg/day) (33) model of ischemic stroke. Also our results are consistent with other non-urea-based sEH inhibitors such as 4-PCO (4-phenyl chalcone oxide) that have been shown to produce neuroprotection in stroke models (18a). This study for the first time showed that infarct volume reduction was associated with a twofold elevation of the cumulative EETs-to-DHETs ratio in brain cortex with t-AUCB treatment. Analysis of brain cortices by our validated ultra performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method demonstrated no significant changes in the levels of metabolites produced from CYP4A, CYP4F, and the COX pathway, thereby indicating the specificity and selectivity of sEH inhibition by t-AUCB. Together, these findings suggest that low-dose t-AUCB selectively alters EETs concentrations and significantly reduces infarct volume after a single-dose administration in the rat MCAO model.

Based on these results, we delineated the impact acute sEH inhibition had on behavioral performance. Our findings suggest that acute administration of t-AUCB significantly improved behavioral performance following post-ischemic reperfusion. The behavioral tests used to assess MCAO damage have been shown to correlate with the duration of ischemia and relate to the degree of behavioral deficit (3). Acute treatment with t-AUCB at the time of ischemic injury exerted beneficial effects on days 1 and 2 following reperfusion. The data from these behavioral performance tests suggest that the extent of cortical damage was more severe in vehicle-treated rats after MCAO when compared with t-AUCB-treated animals and that the rats recovered significantly from cortical damage and sensory neglect after acute t-AUCB administration. Taken together, these data demonstrate that selectively increasing brain cortical EETs concentrations by acute sEH inhibition may not only reduce infarct volume but also improves the neurofunctional outcome in rats after MCAO, thereby providing additional evidence in support of sEH inhibitors as potential therapeutic intervention for neuroprotection after ischemic injury.

The data from infarct volume and behavioral performance assessments led us to investigate the factors contributing to the neuroprotective effects of t-AUCB. We used a noninvasive ASL-MRI imaging technique to evaluate real-time CBF analysis. We found that acute t-AUCB treatment produced a nonsignificant trend toward improved CBF around the infarcted area during the post-ischemic hypoperfusion period with no major differences in CBF observed either during or after ischemia. Our findings after ischemic injury were similar to the results reported previously showing no significant differences in regional CBF rates as measured by [14C]-iodoantipyrene [IAP] autoradiography between AUDA-nBE and vehicle-treated groups (41). Conversely, in another study, Zhang et al. (42) reported that brain tissue perfusion was significantly higher in sEH null mice (sEH−/−) compared with wild-type mice during and after vascular occlusion by Laser-Doppler perfusion and [14C]-IAP autoradiography. One of the likely explanations for the contradictory findings between sEH−/− phenotype and chemical sEH inhibition is related to acute chemical sEH inhibition versus chronic loss of activity in sEH−/− mice producing differential effects on CBF. It is also possible that developmental differences or loss of phosphatase activity in the sEH−/− animals may explain the observed CBF effects as suggested by Keseru et al. (20) in a study evaluating hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. In this study, Keseru et al. (20) observed increased right heart hypertrophy and pulmonary artery muscularization in sEH−/− mice subjected to chronic hypoxia than the wild-type mice treated chronically with sEH inhibitors. Collectively, these studies support that the phenotype differences exist between sEH chemical inhibition and sEH−/− animals. More studies focusing on CBF changes should be completed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of these phenotypic differences and to better understand the degree to which changes in CBF within microvessels contribute to overall neuroprotection within the neurovascular unit.

Given that acute administration did not significantly affect CBF in the rat MCAO model, we sought to determine if t-AUCB directly protects neurons from ischemic damage in vitro. Our in vitro experiments with naïve rat primary cortical neurons showed that t-AUCB significantly reduced neuronal cell death in a concentration-dependent manner after hypoxic injury, thereby suggesting a direct neuroprotective effect of t-AUCB treatment under hypoxic conditions. t-AUCB did not show any effect under nonhypoxic conditions, suggesting that the effect is specific to the injury mechanisms initiated during hypoxia. In our assay negative control MK-801, a potent NMDA receptor antagonist prevented neuronal death significantly after hypoxic injury, suggesting that involvement of excitotoxic mechanisms for neuronal death; however, it is unknown whether the protective mechanisms of the EETs are identical in vivo versus in vitro. Future studies comprehensively evaluating the protective mechanisms will help understand the similarity of in vitro protective mechanisms to the in vivo mechanisms. Furthermore, our findings are consistent with the data published by Koerner et al. (22), who reported that polymorphisms in the sEH gene that alter hydrolase activity of sEH are linked to neuronal survival in an in vitro oxygen-glucose deprivation study with primary rat cortical neurons. In this experiment, Koerner et al. (22) showed that overexpression of wild-type sEH resulted in an increase in OGD-induced neuronal death, which was reversed by exogenous addition of excess 14,15-EET. Also, a mutant of sEH with decreased hydrolase activity showed significant reduction in cell death compared with untreated cells. In addition to the cytoprotective effect on neurons, EETs also appear to exert beneficial effects on other brain cells in ischemia as reported by Liu and Alkayed (24), who showed cytoprotective effects of exogenous administration of EETs on cortical astrocyte culture in an OGD model. Although, we studied the neuroprotective mechanisms in vitro and CBF changes in vivo, we observed significant improvements in infarct volume reduction and behavioral performance in the absence of a significant CBF improvement, suggesting that the protective effects are due to both direct effect on neurons and additional contributions from CBF changes. Future studies evaluating EET agonists and antagonists that evaluate microvascular flow will aid in the elucidation of the mechanisms of neuroprotection. Furthermore, evaluating the effect of sEH inhibition on oxidative stress and inflammation accompanying ischemic damage of cerebral tissue will elucidate underlying effector mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis. Although we did not observe significant changes in the levels of key prostaglandin metabolites across treatment groups, future studies evaluating the levels of key oxidative stress markers such as 8-isoprostane will help in elucidating the underlying mechanisms of pathogenesis of ischemic injury. Collectively, these data suggest that altering EETs levels by acute inhibition of sEH is likely to produce the largest benefits by affecting multiple components of neurovascular unit such as astrocytes, neurons, and microvascular flow.

One of the limitations in our current study was the administration of t-AUCB at the time of initiation of ischemia. Due to the difficulty in administering t-AUCB post-ischemic injury in our MCAO model in CBF assessment experiments by ASL-MRI, we administered t-AUCB immediately before initiation of ischemic injury in all of our experiments. Future direction of our work includes evaluating the neuroprotective effects of t-AUCB administered with the same dosing regimen (0.9 mg/kg iv) during the post-ischemic reperfusion period. A second limitation of our study was that in our in vitro cell culture experiments, we used high concentrations of t-AUCB (0.5 μM) to account for possible loss due to nonspecific binding to cells and metabolism after uptake. This concentration may not be reflective of intracellular concentrations achieved with our dosing regimen (37). Future goals of our work will aim at assessing the in vitro neuroprotective efficacy of t-AUCB over a wider concentration and time exposure range. A third limitation of our study was that t-AUCB neuroprotection was evaluated in male rats alone. A previous study has showed that sEH expression in females was lower than males and that the gene deletion of sEH did not reduce infarct volume in females, presumably due to lower sEH expression (40). Future studies are needed to evaluate acute and/or chronic sEH inhibition in female rats to understand whether gender difference plays a crucial role in sEH mediated neuroprotective effects.

Conclusion

In summary, in the current study we have demonstrated the neuroprotective effects of t-AUCB in a rat MCAO model at a low dose and have produced the first evidence that t-AUCB alters EETs-to-DHETs ratio without significant changes in other AA metabolites from CYP4A, CYP4F, and COX pathways. In addition, these data are first to demonstrate improved short-term behavioral performance by t-AUCB, thereby providing evidence that sEH inhibitors meet the STAIR criteria of improved functional outcome in the rat. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the neuroprotection by t-AUCB is likely due to direct neuronal effects with minor contributions from alterations in CBF. Chronic sEH inhibition by pharmacological inhibitors is an area of the future study to better elucidate long-term behavioral performance and evaluate sEH inhibitors as a potential novel intervention for focal ischemic insults.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NIEHS R01 ES002710 (to B. D. Hammock), NIH/NIEHS R01 ES013933 (to B. D. Hammock), the NIH Counter Act Program (to B. D. Hammock), NINDS U54 NS079202 (to B. D. Hammock), NINDS R01NS052315 (to S. M. Poloyac), and NCRR S10RR023461 (to S. M. Poloyac).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.S.B.S. and S.M.P. conception and design of research; J.S.B.S., M.A., W.L., M.E.R., L.M.F., and K.T.H. performed experiments; J.S.B.S. analyzed data; J.S.B.S. interpreted results of experiments; J.S.B.S. prepared figures; J.S.B.S. drafted manuscript; J.S.B.S., M.A., M.E.R., L.M.F., K.T.H., S.H.G., S.H.H., B.D.H., and S.M.P. edited and revised manuscript; J.S.B.S., M.A., W.L., M.E.R., L.M.F., K.T.H., S.H.G., S.H.H., B.D.H., and S.M.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present address of Muzamil Ahmad: Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Neuropharmacology Laboratory, Srinagar (J&K), India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Kogure K, Yamamoto H, Imazawa M, Miyamoto K. Mechanism of arachidonic acid liberation during ischemia in gerbil cerebral cortex. J Neurochem 48: 503–509, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkayed NJ, Birks EK, Hudetz AG, Roman RJ, Henderson L, Harder DR. Inhibition of brain P-450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase decreases baseline cerebral blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1541–H1546, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronowski J, Samways E, Strong R, Rhoades HM, Grotta JC. An alternative method for the quantitation of neuronal damage after experimental middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats: analysis of behavioral deficit. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16: 705–713, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskaya MK, Prasad MR, Donaldson D, Hu Y, Rao AM, Dempsey RJ. Enhanced accumulation of free fatty acids in experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 54: 167–171, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazan NG. Free arachidonic acid and other lipids in the nervous system during early ischemia and after electroshock. Adv Exp Med Biol 72: 317–335, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bazan NG., Jr Effects of ischemia and electroconvulsive shock on free fatty acid pool in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta 218: 1–10, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell WB, Falck JR. Arachidonic acid metabolites as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Hypertension 49: 590–596, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caro AA, Cederbaum AI. Role of cytochrome P450 in phospholipase A2- and arachidonic acid-mediated cytotoxicity. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 364–375, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan PH, Fishman RA. The role of arachidonic acid in vasogenic brain edema. Fed Proc 43: 210–213, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiamvimonvat N, Ho CM, Tsai HJ, Hammock BD. The soluble epoxide hydrolase as a pharmaceutical target for hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 50: 225–237, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey RJ, Roy MW, Meyer K, Cowen DE, Tai HH. Development of cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid after transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurosurg 64: 118–124, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med 23: 37–45, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorrance AM, Rupp N, Pollock DM, Newman JW, Hammock BD, Imig JD. An epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, 12-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)dodecanoic acid (AUDA), reduces ischemic cerebral infarct size in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 46: 842–848, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, Lo EH. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke 40: 2244–2250, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardiner M, Nilsson B, Rehncrona S, Siesjo BK. Free fatty acids in the rat brain in moderate and severe hypoxia. J Neurochem 36: 1500–1505, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hao CM, Breyer MD. Physiologic and pathophysiologic roles of lipid mediators in the kidney. Kidney Int 71: 1105–1115, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrich KS, Kochanek PM, Williams DS, Schiding JK, Marion DW, Ho C. Early perfusion after controlled cortical impact in rats: quantification by arterial spin-labeled MRI and the influence of spin-lattice relaxation time heterogeneity. Magn Reson Med 42: 673–681, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iliff JJ, Alkayed NJ. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition: targeting multiple mechanisms of ischemic brain injury with a single agent. Future Neurol 4: 179–199, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Iliff JJ, Jia J, Nelson J, Goyagi T, Klaus J, Alkayed NJ. Epoxyeicosanoid signaling in CNS function and disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 91: 68–84, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imig JD. Epoxides and soluble epoxide hydrolase in cardiovascular physiology. Physiol Rev 92: 101–130, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keseru B, Barbosa-Sicard E, Schermuly RT, Tanaka H, Hammock BD, Weissmann N, Fisslthaler B, Fleming I. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension: comparison of soluble epoxide hydrolase deletion vs. inhibition. Cardiovasc Res 85: 232–240, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler RC, Gebremedhin D, Harder DR. Role of astrocytes in cerebrovascular regulation. J Appl Physiol 100: 307–317, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koerner IP, Jacks R, DeBarber AE, Koop D, Mao P, Grant DF, Alkayed NJ. Polymorphisms in the human soluble epoxide hydrolase gene EPHX2 linked to neuronal survival after ischemic injury. J Neurosci 27: 4642–4649, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W, Wu S, Hickey RW, Rose ME, Chen J, Graham SH. Neuronal cyclooxygenase-2 activity and prostaglandins PGE2, PGD2, and PGF2 alpha exacerbate hypoxic neuronal injury in neuron-enriched primary culture. Neurochem Res 33: 490–499, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu M, Alkayed NJ. Hypoxic preconditioning and tolerance via hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) 1alpha-linked induction of P450 2C11 epoxygenase in astrocytes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 25: 939–948, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu M, Hurn PD, Alkayed NJ. Cytochrome P450 in neurological disease. Curr Drug Metab 5: 225–234, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller TM, Donnelly MK, Crago EA, Roman DM, Sherwood PR, Horowitz MB, Poloyac SM. Rapid, simultaneous quantitation of mono and dioxygenated metabolites of arachidonic acid in human CSF and rat brain. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 877: 3991–4000, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moncada S, Vane JR. Pharmacology and endogenous roles of prostaglandin endoperoxides, thromboxane A2, and prostacyclin. Pharmacol Rev 30: 293–331, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poloyac SM, Tortorici MA, Przychodzin DI, Reynolds RB, Xie W, Frye RF, Zemaitis MA. The effect of isoniazid on CYP2E1- and CYP4A-mediated hydroxylation of arachidonic acid in the rat liver and kidney. Drug Metab Dispos 32: 727–733, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy TS, Bazan NG. Arachidonic acid, stearic acid, and diacylglycerol accumulation correlates with the loss of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in cerebrum 2 seconds after electroconvulsive shock: complete reversion of changes 5 minutes after stimulation. J Neurosci Res 18: 449–455, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehncrona S, Mela L, Siesjo BK. Recovery of brain mitochondrial function in the rat after complete and incomplete cerebral ischemia. Stroke 10: 437–446, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen HC, Hammock BD. Discovery of inhibitors of soluble epoxide hydrolase: a target with multiple potential therapeutic indications. J Med Chem 55: 1789–1808, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimizu S, Nagayama T, Jin KL, Zhu L, Loeffert JE, Watkins SC, Graham SH, Simon RP. bcl-2 Antisense treatment prevents induction of tolerance to focal ischemia in the rat brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21: 233–243, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simpkins AN, Rudic RD, Schreihofer DA, Roy S, Manhiani M, Tsai HJ, Hammock BD, Imig JD. Soluble epoxide inhibition is protective against cerebral ischemia via vascular and neural protection. Am J Pathol 174: 2086–2095, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spector AA, Fang X, Snyder GD, Weintraub NL. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs): metabolism and biochemical function. Prog Lipid Res 43: 55–90, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spector AA, Norris AW. Action of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cellular function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C996–C1012, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swanson RA, Morton MT, Tsao-Wu G, Savalos RA, Davidson C, Sharp FR. A semiautomated method for measuring brain infarct volume. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10: 290–293, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai HJ, Hwang SH, Morisseau C, Yang J, Jones PD, Kasagami T, Kim IH, Hammock BD. Pharmacokinetic screening of soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors in dogs. Eur J Pharm Sci 40: 222–238, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unterberg A, Wahl M, Hammersen F, Baethmann A. Permeability and vasomotor response of cerebral vessels during exposure to arachidonic acid. Acta Neuropathol 73: 209–219, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams DS, Detre JA, Leigh JS, Koretsky AP. Magnetic resonance imaging of perfusion using spin inversion of arterial water. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 212–216, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Iliff JJ, Campbell CJ, Wang RK, Hurn PD, Alkayed NJ. Role of soluble epoxide hydrolase in the sex-specific vascular response to cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 29: 1475–1481, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W, Koerner IP, Noppens R, Grafe M, Tsai HJ, Morisseau C, Luria A, Hammock BD, Falck JR, Alkayed NJ. Soluble epoxide hydrolase: a novel therapeutic target in stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 27: 1931–1940, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang W, Otsuka T, Sugo N, Ardeshiri A, Alhadid YK, Iliff JJ, DeBarber AE, Koop DR, Alkayed NJ. Soluble epoxide hydrolase gene deletion is protective against experimental cerebral ischemia. Stroke 39: 2073–2078, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]