Abstract

To explore the disassembly mechanism of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), a model system for virus study, during infection, we have used single-molecule force spectroscopy to mimic and follow the process of RNA disassembly from the protein coat of TMV by the replisome (molecular motor) in vivo, under different pH and Ca2+ concentrations. Dynamic force spectroscopy revealed the unbinding free-energy landscapes as that at pH 4.7 the disassembly process is dominated by one free-energy barrier, whereas at pH 7.0 the process is dominated by one barrier and that there exists a second barrier. The additional free-energy barrier at longer distance has been attributed to the hindrance of disordered loops within the inner channel of TMV, and the biological function of those protein loops was discussed. The combination of pH increase and Ca2+ concentration drop could weaken RNA-protein interactions so much that the molecular motor replisome would be able to pull and disassemble the rest of the genetic RNA from the protein coat in vivo. All these facts provide supporting evidence at the single-molecule level, to our knowledge for the first time, for the cotranslational disassembly mechanism during TMV infection under physiological conditions.

Introduction

Study of the mechanism of virus assembly and disassembly is of paramount importance in the control of virus infection. Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) was the first virus to be discovered, and has been used as a model system for virus study since its discovery more than a century ago (1–12). TMV is a rod-shaped virus, 300 nm in length and 18 nm in diameter, with a central channel of ∼4 nm in diameter. Approximately 2130 identical protein subunits, each with a molecular mass of 17,500 Da, form a helix with 161/3 subunits in every turn, protecting a single-strand RNA that follows the basic helix groove among the protein subunits at a diameter of 8 nm (6). During the past century, scientists have designed many experiments to explore the mechanism of TMV disassembly/assembly, because such information is of great importance for preventing TMV infection. Based on the crystal structure of TMV together with other experimental results, Namba et al. (6) and Stubbs (7) have proposed that when a virion first enters a plant cell, the decrease in calcium concentration and a raised pH (relative to the extracellular environment) removes protons and calcium ions from the carboxyl-carboxylate and carboxylate-phosphate pairs, allowing electrostatic repulsive forces from the negative charges to destabilize the virus. The in vitro experiments by Wilson (8) and Mundry et al. (9) have shown that mild alkaline pretreatment destabilizes the TMV particle at the 5′-end, resulting in the uncoating of the leader sequence, which is sufficient to expose the first start codon of the RNA (10) and facilitate the loading of the ribosomal proteins. However, there is evidence that TMV RNA is not destabilized by pretreatment (at higher pH 8), but is still capable of being disassembled in vivo. Although it has been suggested that the disassembly process of TMV during the early stage of TMV infection follows the cotranslational disassembly mechanism (i.e., the TMV particles disassemble gradually during the translation) (8,11,12), direct evidence at the molecular level is needed. For example, it is not clear at neutral pH (without the alkaline pretreatment) if the 5′-end of TMV particle is destabilized and the corresponding RNA is exposed for the subsequent ribosome loading. Will the molecular motor be able to further disassemble the RNA from the protein coat? A better understanding of the TMV disassembly process, and how to control and modulate it, will shed light on effective plant protection and the development of new antivirus drugs. In addition, the study of virus disassembly on such model systems may help us understand the infection mechanism of other viruses.

AFM-based single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) has the capability to measure the interacting forces between biomolecules under physiological conditions with picoNewton (pN) sensitivity (13–35). In addition, recent studies have shown that by elaborate experimental design/control, AFM-based SMFS can be used to investigate molecular interactions (or monitor the biological processes) in material or biological systems (36–42). Apart from direct quantitative investigation of intra- and intermolecular interactions, SMFS is also advantageous in offering information on the prominent barriers traversed in the free-energy landscape along their force-driven unbinding pathways. In this direction, dynamic force spectroscopy (DFS) experiments, in which molecular bonds are dissociated at different timescales, are quite useful. So far, DFS has been used successfully to disclose the energy landscapes for ligand-receptor interactions (43–45), DNA melting (46), unfolding of proteins (47,48), and the adhesion of biological cells (49), providing deep insight into the nature of those molecular interactions.

In this article, on the basis of our previously established method (36), we move one step further to apply SMFS to investigate the mechanism of RNA disassembly from the protein coat of TMV under physiological conditions during infection. To do that, DFS is employed to explore the unbinding free-energy landscapes of RNA-coat protein complexes under different pH (4.7 and 7.0) and EDTA concentrations, respectively. Our results show that with the increase of pH, the unbinding force between genetic RNA and coat protein is reduced remarkably. And decrease of calcium ion concentration weakens the interactions between RNA and coat protein, but only at or near the 5′-end of TMV and not at other locations. Based on these results, the molecular mechanism of RNA disassembly from TMV during the early state of TMV infection is proposed.

Methods

Materials

Wild-type TMV particles were prepared as described in Niu et al. (50). A TMV mutant, TMV1cys (an additional cysteine residue was added to the amino terminus of the virus coat protein), was prepared using the same procedure as described by Royston et al. (51). Ultrapure deionized water (18.2 MΩ⋅cm) was obtained from a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with pH 4.7 and 7.0 was prepared by 1), titrating Na2HPO4 (0.1 M) into NaH2PO4 (0.1 M) to get a final pH of 4.7; and 2), titrating NaH2PO4 (0.1 M) into Na2HPO4 (0.1 M) to get a final pH of 7.0. A quantity of 50 or 100 mM EDTA-PBS solution was prepared by dissolving EDTA powder into PBS buffer (3-APDMES [3-aminopropyldimethylepoxysilane] FluoroChem, Hadfield, Derbyshire, UK) of pH 4.7.

Immobilization of TMV sample and functionalization of AFM tips

TMV particles were immobilized on the gold substrate by immersing cleaned gold substrates into a TMV (0.5 mg/mL)-PBS solution for 3 h at pH 4.7, which were then rinsed with the same PBS buffer before the pulling experiment. For those experiments performed at pH 7.0, TMV particles were first adsorbed on a gold substrate at pH 4.7 in the same fashion as mentioned above and then a PBS buffer of pH 7.0 was used during the stretching experiment. Si3N4 AFM tips were immersed in a piranha solution (H2SO4/30% H2O2, v/v = 7:3) for 5 min, rinsed with copious amounts of water, and dried in an oven. Then the tips were modified with 3-APDMES to increase the probability of picking up an RNA molecule (52).

SMFS and DFS

Single-molecule force spectroscopy experiments were carried out using a NanoWizard II BioAFM (JPK Instrument, Berlin, Germany) in contact mode at room temperature in PBS at pH 4.7 and 7.0, respectively. Standard V-shaped Si3N4 tips (MSCT; Bruker, Camarillo, CA) with five triangular cantilevers and one rectangular cantilever were used. Spring constants of the AFM cantilevers were calibrated using the thermal noise method (53,54). The measured values ranged from 15 to 20 mN/m. In our experiment, a contact force ∼1.5 nN was applied between the AFM tip and the sample with duration of 0.3 s. To perform the DFS measurement, we recorded force versus extension traces at a pulling rate ranging from 30 nm/s (loading rate 0.59 nN/s) to 2500 nm/s (loading rate 48.85 nN/s), with a constant approaching rate of 2500 nm/s. For each pulling rate, 250 peaks were analyzed and the force distribution histograms were fitted to Gaussian functions to get the most probable unbinding forces and standard deviations. The loading rate was determined by multiplying the stretching rate with the slope of peak near the rupture point on the sawtooth-like plateaus. To minimize the effect of the RNA linker on the apparent slope (i.e., the spring constant) of the system, statistical analysis on the apparent spring constants was performed (by using ∼400 data points) to get the most probable spring constant (19.54 ± 9.28 pN/nm), which was then used for the determination of the loading rate. For the force-clamp experiment, the adjacent steps in the height-time curves were identified and measured by using the step-fitting function (55) of the data processing software provided by the manufacturer of our NanoWizard II BioAFM (JPK Instrument). The step-fitting function finds steps in the height-time curve data by fitting a model that is a combination of sharp steps with a slowly varying background (55). The step sizes (height) were exported as a plain text file, and a histogram of the step-size distribution was constructed with the software IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

Results and Discussion

pH-dependence of unbinding forces between RNA and coat protein

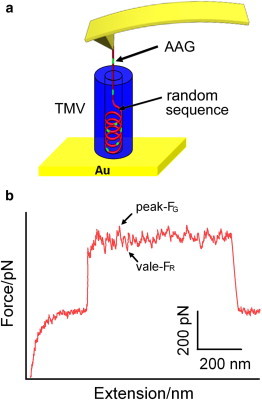

In our previous studies, we have shown that, to investigate molecular interactions in relatively complex systems (including in condensed material and/or biological systems), a carefully tailored experimental design, such as with a sample preparation method, is of crucial importance (36,37). By introducing an additional cysteine residue to the amino terminus of the virus coat protein, the TMV particle can be perpendicularly immobilized on a gold substrate. This is likely done by their 3′ ends (the ends of TMV particle are named after the corresponding RNA ends) because the cysteine residues at the 3′ ends are more accessible to the gold surface (51), via gold-thiol chemistry leaving the 5′ ends exposed for picking up by AFM tip (36,51). In addition, a previous study also showed that even wild-type TMV particles could be immobilized perpendicularly on the gold substrate under lower pH (36). An upright configuration of the TMV particle on the gold substrate will facilitate picking up and eventually pulling the RNA genome out of the plant virus. As illustrated in Fig. 1 a, the TMV particles are first perpendicularly immobilized on a gold substrate. Then the AFM tip is brought to contact with the asymmetric 5′ opening of the immobilized TMV particles (36,51), which makes close contact of the 5′ RNA genome with the AFM tip and subsequent RNA-AFM tip attachment possible. Our results show that an amino-group-functionalized AFM tip can make the probability of RNA-AFM tip attachment more consistent and reproducible as compared with that of bare Si3N4 tip. This may be due to the stronger electrostatic (as well as hydrogen-bonding) interactions between amine-group and RNA fragment. When the AFM tip is retracted from the sample surface the RNA can be pulled step-by-step out of the TMV particle, producing the sawtooth-like force plateau on the stretching curve, as shown in Fig. 1 b. It needs to be pointed out that the length of the force plateau will depend on both the z-scan size (the travel distance of the AFM scanner in z direction) and the tip-RNA interactions (see Fig. S1 and Fig. S2 in the Supporting Material for more information).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic illustration of the SMFS experiment. (Red and green color) Random and AAG sequences of RNA, respectively. (b) A typical force-extension curve containing the sawtooth-like plateau obtained by pulling the RNA out of the TMV particle. FG (the peak) and FR (the vale) represent the unbinding forces of AAG sequences and other random sequences, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

On the sawtooth-like force plateau, peaks and vales appear by turns. It has been reported that the affinity between AAG sequences and the coat protein, is the strongest among all of the RNA-coat protein complexes (56). So those peaks on the sawtooth-like plateau may correspond to the unbinding force between AAG sequences of the RNA and coat protein (36), named FG, whereas the vales may correspond to the unbinding force between the rest, i.e., random sequences of the RNA and coat protein, named FR. In other words, those vales can be looked on as the minimum/basic forces required to unbind general RNA fragments from the protein coat, whereas the peaks represent the unbinding of specific RNA sequences (e.g., AAG-rich sequence) from the protein coat.

Earlier in vitro experiments have shown that pretreatment of TMV particles by alkaline alters the stability of the virus particle (8,9). In addition, it is also believed that upon entering the plant cell, TMV particles will experience an increase in pH. To understand the effects of pH on the stability of the TMV particles and RNA-protein interactions, SMFS experiments were performed at pH 4.7 and 7.0, respectively.

There are two reasons for choosing those two values of pH:

-

1.

We want to see the effect of pH on the protein loops on the inside wall of TMV particle; it has been reported that at pH < 6, the loops exist as more-ordered structures compared with those at pH 7.0.

-

2.

pH 4.7 can facilitate the attachment of TMV particle to the gold substrate in an upright fashion (51).

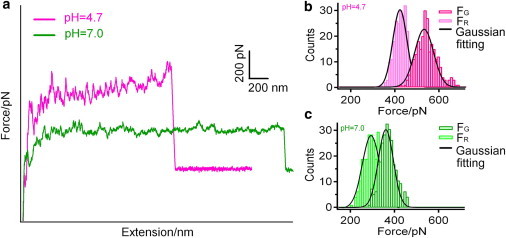

Hundreds of sawtooth-plateau-containing force-extension curves (Fig. 2 a) were obtained under these two conditions, and the corresponding unbinding forces, FG and FR, were measured, respectively. The forces were plotted as histograms and then fitted by Gaussian functions to yield the most probable unbinding forces with standard deviations. At pH 4.7, FG and FR are 533 ± 42 and 423 ± 32 pN, with a fluctuation of 110 pN (Fig. 2 b), whereas at pH 7.0, FG and FR are 361 ± 33 and 295 ± 39 pN, with a fluctuation of 66 pN (Fig. 2 c). Both FG and FR are larger at pH 4.7 compared to pH 7.0, suggesting that the RNA fragments disassemble easier from the protein coat at pH 7.0.

Figure 2.

(a) Superposition of typical sawtooth-like plateaus obtained at pH 4.7 (pink curve) and 7.0 (green curve), respectively. (b) Histograms of unbinding forces FG (dark pink) and FR (light pink) at pH 4.7. (c) Histograms of unbinding forces FG (dark green) and FR (light green) at pH 7.0. Each histogram contains 250 events with force-loading rate of 29.31 nN/s and is fitted to a Gaussian function (black). To see this figure in color, go online.

Our results agree well with the earlier findings by Steckert and Schuster (56), who observed much stronger binding between RNA and coat protein at pH 5 than at pH 7 during their equilibrium dialysis binding experiments. The interactions between RNA and coat protein can be classified into three categories: electrostatic interactions between the phosphate groups and protein side chains; hydrophobic interactions between the bases and the protein; and base-specific hydrogen bonds with the protein (6). As the pH is changed from 4.7 to 7.0, the interactions between phosphate groups and arginine residues are weakened due to decreased density of positive charges on the arginine residues, and at the same time, hydrogen bonds formed between the N-6 atom in adenine and the main-chain carbonyl group of Thr89 are weakened (6). These two factors have contributed to the weakened RNA-coat protein interactions upon pH variation from 4.7 to 7.0.

Another interesting fact is that the force fluctuation (peak-to-vale) at pH 4.7 is larger than that at pH 7.0, which means that the unbinding force FG (of AAG sequences) decreases faster than FR (of other random sequences) when the pH is changed from 4.7 to 7.0. In other words, the interactions between the AAG sequences of the RNA and coat protein are affected more by pH change than the interactions between other sequences of the RNA and coat protein. This is in agreement with the fact that strong hydrogen-bonding interactions exist between the guanine base and arginine (Arg122) and aspartic acid (Asp115) (56).

DFS investigation of RNA-coat protein unbinding at pH 4.7 and 7.0

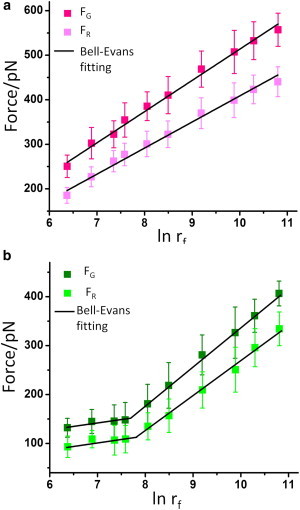

To gain deep insight into the mechanism of TMV disassembly process, DFS was employed to reveal the free-energy landscape of RNA-coat protein complexes at pH 4.7 and 7.0. We explored the dependence of the unbinding forces (FG and FR) on the loading rate (rf), which represents how quickly the force is applied to the complexes. For this purpose, typically 250 curves were recorded at each loading rate ranging from 0.59 to 48.8 nN/s, at pH 4.7 and 7.0, respectively. The unbinding forces at each loading rate were analyzed and plotted as histograms, which were subsequently subjected to Gaussian fitting to get the most probable unbinding forces and standard deviations (as shown in Fig. S3 and Table S1 in the Supporting Material). The most probable unbinding forces, FG and FR, are plotted against the logarithm of the loading rate, ln rf, in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

The most probable unbinding forces FG and FR between the RNA and coat protein as functions of the loading rate at (a) pH 4.7 and (b) pH 7.0. Error bars are standard deviations. To see this figure in color, go online.

The results show that the unbinding forces, FG and FR, increase linearly with logarithm of the loading rate in the range of 0.59–48.8 nN/s. This means that both FG and FR are loading rate-dependent, and these two unbinding processes occur in a nonequilibrium state at the timescale of our experiment (57). At each loading rate, the discrepancy between FG and FR at pH 4.7 is larger than that at pH 7.0, which means that FG is more sensitive to the pH change in the loading rate range explored. In addition, under both pH conditions the discrepancy between the two unbinding forces increases with the loading rate, which means that FG is more sensitive than FR to the loading rate.

The data of the most-probable unbinding forces, versus ln rf, fit well to the Bell-Evans model (as shown in Fig. 3; see the Supporting Material for a detailed description of the fitting process). The Bell-Evans model has been used frequently to describe the influence of an external force on the rate of noncovalent bond dissociation (58,59).

When a constant external force, F, is applied to the complex of RNA and coat protein, the unbinding is facilitated by a lowered free-energy barrier, resulting in an increased off-rate constant, according to Eqs. 1 and 2 (59):

| (1) |

| (2) |

where ΔE≠ and koff are the free-energy barrier and off-rate constant of the complex in the absence of a force, and ΔE≠ (F) and koff (F) are the corresponding variables in the presence of an applied force. The value kB denotes the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin (kBT = 4.11 pN·nm at 298 K). The value χβ is the effective distance between the bound state and the transition state projected along the direction of the applied force.

Equation 3 predicts a linear relationship between the unbinding force F and ln rf. The slope of the line correlates with the free-energy barrier along the reaction coordinate of the RNA-coat protein complex, yielding χβ. By extrapolating the fit to zero external force, one can derive another important parameter, koff, which is the natural thermal off-rate for the system. The binding lifetime τ is correlated with koff by equation τ = 1/koff:

| (3) |

According to transition state theory, the off-rate constant, koff, is a function of the free-energy barrier ΔE,

| (4) |

Therefore, the difference in the free-energy barrier of different transition states (ΔΔE = ΔEa − ΔEb) can be determined by Eqs. 5 and 6:

| (5) |

| (6) |

Table 1 shows these parameters derived by fitting Eq. 3 to experimental data shown in Fig. 3. At the same time, the differences of free-energy barriers (ΔΔE) under different pH are also shown. These kinetic parameters are reasonable as compared to that obtained in other similar biological systems (60–63). For example, in those studies on (strept)avidin-biotin interactions, at least two free-energy barriers have been found: one with a very narrow width (χβ ≤ 0.1 nm) and the other with a large one (χβ ≥ 0.4 nm). The narrow inner energy barrier has been attributed to the breakage of hydrogen bonds between biotin and streptavidin in their recent work by Teulon et al. (62). In our case, the narrow free-energy barrier located at ∼0.06 (0.05–0.07) nm may be ascribed to the event involved in the breaking of the hydrogen bonds between RNA and coat protein, because the increase of pH from 4.7 to 7.0 has caused a free-energy drop of ∼3 kBT for this energy barrier (see Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for RNA-protein unbinding obtained by dynamic force spectroscopy

| RNA-coat protein | Loading rate (nN/s) | χβ (nm) | koff (s−1) | τ (s) | ΔΔE (kBT) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 4.7 | FG | 0.59–48.8 | 0.060 | 0.19 | 5.26 | — |

| FR | 0.59–48.8 | 0.072 | 0.29 | 3.43 | — | |

| pH 7.0 | FG | 0.59–2.09 | 0.34 | 7.66 × 10−4 | 1.31 × 103 | 5.51 |

| 2.09–48.8 | 0.051 | 4.08 | 0.24 | −3.07 | ||

| FR | 0.59–2.59 | 0.36 | 1.14 × 10−2 | 87.7 | 3.24 | |

| 2.59–48.8 | 0.056 | 7.34 | 0.14 | −3.23 | ||

ΔΔE is relative to the RNA-coat protein unbinding at pH 4.7.

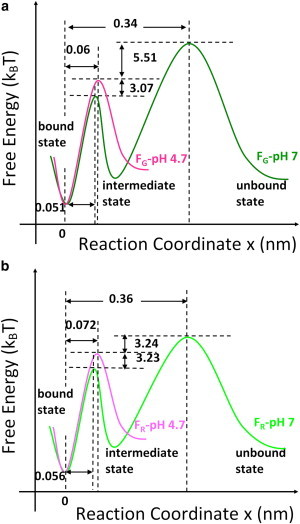

Figure 4.

Conceptual unbinding free-energy landscapes of RNA-coat protein complexes for (a) FG and (b) FR at pH 4.7 (pink line) and 7.0 (green line) without external force, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

pH changes the unbinding free-energy landscape of RNA-coat protein complexes

According to the parameters in Table 1, we can draw the conceptual free-energy landscapes for the unbinding of RNA-coat protein complexes under different conditions, as shown in Fig. 4.

As seen in Fig. 3, at pH 4.7 both FG and FR exhibit one linear region within the range of the experimental loading rate. This indicates that a single free-energy barrier dominates the unbinding, resulting in χβ of 0.06 and 0.072 nm, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4. However, at pH 7.0, both FG and FR exhibit two distinct linear regions within the range of the experimental loading rate, with an initial gradual increase followed by a more rapid increase at a higher loading rate. These data reveal that at pH 7.0 both AAG and other random RNA sequences need to overcome two free-energy barriers and one intermediate state to get disassembled from the protein coat. For the AAG sequence, the two free-energy barriers (χβ) are located at 0.34 and 0.051 nm, respectively; for other random sequences, the barriers are at 0.36 and 0.056 nm, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4. The appearance of the extra free-energy barrier at pH 7.0 indicates that there exist some long-range interactions between the RNA and the coat protein. Therefore, it is interesting to find out what may have contributed to such long-range interactions.

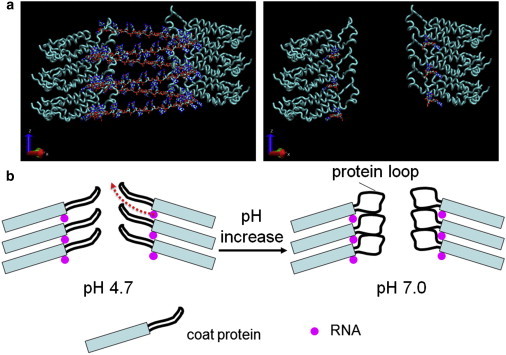

It has been reported that at pH < 6, the loops of polypeptide chain on the inside wall of the TMV particle exist as more-ordered structures, compared to that at pH 7.0 (56), as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

(a) Six subunits of TMV coat protein in a central longitudinal section with the RNA helix (left) and RNA at binding sites only (right). (b) Schematic drawing of pH-induced disordering of the inner loops of a TMV particle. With pH increase from 4.7 to 7.0, the inner loops become disordered. As a result, for the translocation of RNA fragments (red dashed arrow indicates the translocation path) from their binding sites to the outside (i.e., the inner channel), an extra barrier has to be overcome. The TMV structure in panel a was created using the software VMD (65) together with structural data of TMV from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (Piscataway, NJ) Protein Data Bank (PDB:2TMV). To see this figure in color, go online.

Furthermore, recent cryo-electron microscopy results by Ge and Zhou (64) showed nicely the contribution of hydrogen bonds (e.g., between Glu97 and Glu106) to the ordering of the inner loops. Combining these structural characters of TMV (visualized using the software VMD (65)), we speculate that the loop may become disordered when the pH is changed from 4.7 to 7.0 due to the weakened/broken hydrogen bonds (for example, between Glu97 and Glu106). As a result, the translocation path (Fig. 5 b) of the RNA fragment during unbinding will be blocked. Namely, to dissociate completely from the protein coat the RNA fragment needs to unbind from its binding site (the RNA site in Fig. 5) on the protein coat first. Then further dissociation of the detached RNA fragment from the helical groove formed by protein coat is hindered by those disordered loops (Fig. 5 b, right). In other words, at pH 7.0, free-energy barriers with χβ of 0.34 nm (for the AAG sequence) and 0.36 nm (for a random sequence) may correspond to the long-distance hindrance effect of the disordered loop structure on RNA, and the ones with χβ of 0.051 and 0.056 nm arise from the short-distance recognition effect between RNA and coat protein at their binding sites. At pH 4.7, the ordered loop structure does not hinder the dissociation of the partially detached RNA from protein coat (Fig. 5 b, red dashed arrow), so the only free-energy barriers with χβ of 0.06 and 0.072 nm correspond to the short-distance recognition between RNA and coat protein at their binding sites. These results may suggest the interesting possibility that when a TMV virus comes into the plant cell, the interactions between RNA and its protein coat are weakened due to a pH increase, facilitating further disassembly by the replisome. However, the disordered protein rings (loops) still protect the RNA from direct exposure to the cytoplasm (by random diffusion), avoiding digestion of the RNA by the nuclease.

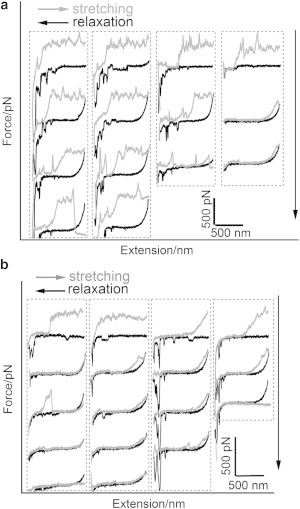

If this hindrance effect of disordered loops on RNA dissociation really exists, it will be more difficult for the detached RNA fragments to find their way back to the helical groove of the protein coat when relaxed. To prove our hypothesis, we performed stretching-relaxation cycles repeatedly under different values of pH (4.7 and 7.0) to compare the probability of reassembly under these two conditions. As shown in Fig. 6 a, at pH 4.7 the sawtooth-like plateau reappears in some of the stretching cycles subsequent to relaxation. This indicates that the detached RNA can find its way back to the protein coat and reassemble. The probability for RNA reassembly is ∼56.5% at pH 4.7, and ∼3.1% at pH 7.0. In addition, at pH 7.0 the sawtooth-like plateau that reappeared during the subsequent stretching is quite short (see Fig. 6 b). This means that, at higher pH, it is difficult for the detached RNA to rebind to the protein coat, and only very short RNA fragments can reassemble. These facts support our hypothesis that the disordered loops prevent the dissociation of RNA from the protein coat at pH 7.0. From Fig. 6 we can also find that there are a few negative peaks on the relaxation/approaching curve. They may come from the interaction between the side wall of AFM tip and some TMV particles, which have been immobilized on the gold substrate perpendicularly (51).

Figure 6.

Typical repeated stretching and relaxation traces of four RNA molecules without rupture at (a) pH 4.7 and (b) pH 7.0, respectively. (Downward arrows) Increasing order of stretching and relaxation cycles.

EDTA weakens the RNA-coat protein interactions at the 5′ end of TMV

Based on the crystal structure of TMV, it has been speculated that the calcium ion utilizes one carboxylate oxygen atom, both phosphate oxygens, the ribose hydroxyl group, and the ring oxygen, together with two water molecules as ligands, to stabilize the virus structure (6). The interactions among the phosphate, carboxylate, and calcium in TMV are presumed to play an important role in the assembly and disassembly of the virus. It is assumed that when a virion first enters a plant cell, the low intracellular calcium concentration and the high pH value (relative to the extracellular environment) remove protons and calcium ions from the two carboxyl-carboxylate pairs and the phosphate-carboxylate calcium site, allowing electrostatic repulsive forces from the negative charges to destabilize the virus (6). The protein-nucleic acid interactions involving the first 69 nucleotides are weaker than the rest of RNA genome because of the absence of guanine bases (66), so the protein subunits forming ∼1.5 turns of the virus helix at the 5′ end are lost.

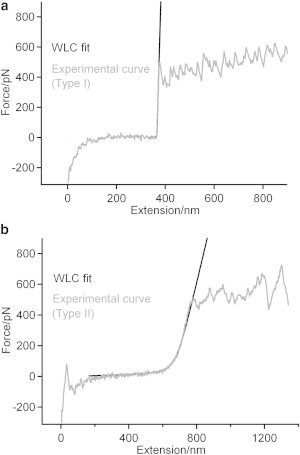

To verify this hypothesis at the single-molecule level, RNA disassembly experiments were performed in the presence of EDTA (0, 50, and 100 mM, respectively), which can chelate calcium ions effectively. Two types of sawtooth-plateau-containing force-extension curves were obtained under these conditions, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Two types of typical sawtooth-like plateau obtained in the presence of 100 mM EDTA at pH 4.7. The force curves are fitted to a wormlike-chain model. The persistence lengths for (a) type I and (b) type II curves are 95 ± 20 and 0.65 ± 0.10 nm, respectively.

In one kind of force curve, the force increases abruptly before the sawtooth-like plateau appears, and in the other, the force increases slowly before the sawtooth-like plateau appears, as seen in Fig. 7 a (or Fig. 2 a) and b, respectively. These two kinds of force curves can both be fitted to a wormlike-chain model (24). For the force curve in Fig. 7 a, the persistence length is ∼95 ± 20 nm, which means that a rigid object has been stretched, corresponding to the stretching of the whole TMV particle by AFM tip before the RNA is pulled out of the particle. For the force curve in Fig. 7 b, the persistence length is ∼0.65 ± 0.10 nm, which means that a flexible polymer chain is stretched, corresponding to stretching of the free RNA detached from the protein coat before it is further detached step by step from the TMV particle.

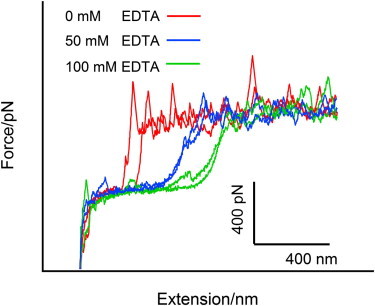

In the absence of EDTA, the probability of getting the force curve (type II) shown in Fig. 7 b is 12.5%, whereas in the presence of 50 and 100 mM EDTA, this probability is increased to 33.9 and 43.1%, respectively. Our previous work shows that the sawtooth-like plateau arises from the sequential unbinding of the RNA genome from the 5′-end opening to the inside of TMV particle (36). Combining these facts, we can deduce that EDTA can chelate calcium ions near the 5′-end of the TMV nanotube to weaken the interactions between the RNA and coat protein, resulting in the detachment of RNA at or near the 5′-end of TMV from protein coat. This result is consistent with the speculation based on the crystal structure of TMV (6). And the probability of initial (5′-end) RNA unbinding from the protein coat increases with EDTA concentration. However, when we superimpose the force curves obtained in the presence of EDTA of different concentrations, we can find that, although the shape of the curves at smaller extensions are quite different, the sawtooth plateaus at longer extensions superimpose on one another very well, as shown in Fig. 8. This means that in other parts of the TMV particle (except that near the 5′-end), the interactions between RNA and the coat protein are hardly affected by EDTA, supporting the cotranslational disassembly mechanism of TMV.

Figure 8.

Superposition of sawtooth-like plateaus obtained in the presence of 0, 50, and 100 mM EDTA, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

The combination of pH increase and Ca2+ concentration drop facilitates the cotranslational disassembly of TMV

From the above discussion, we know that EDTA can only chelate calcium ions at or near the 5′-end of the TMV nanotube. In other words, the decrease of calcium ion concentration only weakens the interactions between the RNA and coat protein at or near the 5′-end of TMV, which can cause the release of the RNA fragment from the protein coat without affecting RNA-protein coat interactions in other parts of TMV. It is believed that upon entering (from an outside environment), the plant cell the TMV particle will encounter a pH increase as well as the [Ca2+] drop. To mimic such an environment change, we investigated the unbinding of RNA-protein coat in the presence of EDTA at higher pH (pH 7.0). Our results show that, in addition to the overall decrease of unbinding force (as discussed above), the probability for detecting free RNA fragments at the 5′-end has increased from 33.9 and 43.1% at pH 4.7 to 51.4 and 59.6% at pH 7.0 in the presence of 50- and 100-mM EDTA, respectively. It is not difficult to imagine that the release of 5′-end RNA fragment will facilitate the loading of the replisome.

We ask: What about the rest of the RNA-coat protein complex? Will the interactions between the RNA and protein coat under high pH be weakened enough that the ribosome can disassemble those RNA-coat protein complexes located far away from the 5′-end during the translation process?

Under optimal conditions, the RNA decoding speed for a ribosome is ∼45 nucleotides/s, which corresponds to an approximate translocation speed of 30 nm/s. Under such a speed, the RNA-coat protein unbinding force is ∼60 pN, as estimated from our SMFS experiment. According to the brilliant work by Vanzi et al. (67), we know that Escherichia coli 70S ribosomes can hold the messenger RNA even at an external force of 100 pN. In addition, the translocation energy during ribosomal protein synthesis is ∼7.3 kcal/mol × 4.2 = 30.66 kJ/mol ≈ 12.4 kT per amino acid (35), which is not very far from the one estimated by our AFM experiment (3 × 0.7 nm × 60 pN ≈ 30 kT). The difference may be ascribed to the different environment inside the plant cell. For example, the pH may be higher than 7.0, which can further weaken the RNA-protein coat interactions as well as slowing translocation speed. These facts indicate that under neutral or higher pH, the replisome will be able to disassemble the RNA from the protein coat of TMV.

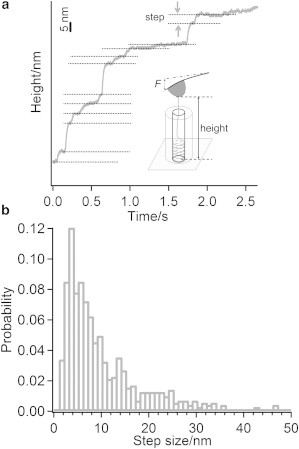

Single-molecule force-clamp experiments reveal the step size of RNA disassembly

Apart from the pulling experiment performed at constant velocity (as discussed above), we have also employed single-molecule force-clamp spectroscopy, which has been used successfully in the study of protein unfolding as well as for disulfide isomerization/reduction in polyproteins (68–70) to investigate the disassembly process in more detail. To accomplish this, a constant force of 50 pN was applied on the RNA picked up by the AFM tip, then the extension/height of the molecule was followed in real-time, as shown in Fig. 9 a. From the figure we can see that the real-time curve shows a stepwise height increase, which corresponds to the gradual detachment of RNA from the protein coat. Statistical analysis has been performed on the step sizes, and the most probable step size is ∼4.2 nm, as shown in Fig. 9 b. When dividing the most probable step size, which is ∼4.2 nm, by 0.68 nm (the rough distance between adjacent bases), we can obtain a step size of approximately six bases. Considering the fact that each coat protein binds to three nucleotides, we can estimate that the RNA fragments unbind from the protein coat in the fashion of two proteins per step during the disassembly. To our knowledge, this is the first study providing such quantitative information on the disassembly, although more investigations are needed to explore the mechanism behind this.

Figure 9.

The single-molecule force-clamp experiment on RNA disassembly. (a) One typical trace that shows stepwise increase of the height. (b) Histogram of the step-size distribution obtained under a loading force of 50 pN.

Conclusion

In summary, we have directly investigated the process of RNA disassembly from its protein coat at the single-molecule level by mimicking the solution environment of TMV disassembly in vivo. When the pH condition is changed from 4.7 to 7.0, the unbinding forces between RNA genome and coat protein are reduced so much that the replisome (molecular motor) will be able to disassemble the RNA from the protein coat of the TMV particle. Using DFS, we have revealed the unbinding free-energy landscapes at pH 4.7 and 7.0, and the additional free-energy barrier at longer distances for pH 7.0 may come from the hindrance of disordered loops within the inner channel of TMV. To our knowledge, this is the first experiment to characterize the free-energy landscapes of the disassembly process of RNA from its protein coat.

Our results also demonstrate that the decrease of calcium ion concentration weakens the interactions between RNA and coat protein at or near the 5′-end of TMV, but does not affect other parts of TMV. So the process of RNA disassembly from protein coat of TMV particle in plant cell is revealed: upon entering the plant cell, the RNA fragment near the 5′-end of TMV detaches first because of lower calcium-ion concentration and pH increase, which facilitates the loading of replisome; the pH increase also facilitates further RNA disassembly by the replisome during translation, so that most of the RNA fragment is protected from digestion before the replication/translation starts. Our research provides direct molecular evidence on the mechanism of cotranslational disassembly during the early stages of TMV infection. The established method can also be used to investigate the disassembly mechanism in other (tubular) virus systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Hermann E. Gaub (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität) for helpful discussions.

N.L. and W.Z. acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 91127031, 20921003, 21221063 and 21204034). W.Z. acknowledges support from the National Basic Research Program (grant No. 2013CB834503), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars (State Education Ministry, SEM), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University, and the State Key laboratory. Q.W. acknowledges support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant No. CHE-0748690) and the Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar Award.

Contributor Information

Qian Wang, Email: wang@mail.chem.sc.edu.

Wenke Zhang, Email: zhangwk@jlu.edu.cn.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Stubbs G., Warren S., Holmes K. Structure of RNA and RNA binding site in tobacco mosaic virus from 4-Å map calculated from x-ray fiber diagrams. Nature. 1977;267:216–221. doi: 10.1038/267216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloomer A.C., Champness J.N., Klug A. Protein disk of tobacco mosaic virus at 2.8 Å resolution showing the interactions within and between subunits. Nature. 1978;276:362–368. doi: 10.1038/276362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison B.D., Wilson T.M. Milestones in the research on tobacco mosaic virus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1999;354:521–529. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klug A. The tobacco mosaic virus particle: structure and assembly. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1999;354:531–535. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namba K., Stubbs G. Structure of tobacco mosaic virus at 3.6 Å resolution: implications for assembly. Science. 1986;231:1401–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.3952490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Namba K., Pattanayek R., Stubbs G. Visualization of protein-nucleic acid interactions in a virus. Refined structure of intact tobacco mosaic virus at 2.9 Å resolution by x-ray fiber diffraction. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;208:307–325. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stubbs G. Tobacco mosaic virus particle structure and the initiation of disassembly. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1999;354:551–557. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson T.M.A. Cotranslational disassembly of tobacco mosaic virus in vitro. Virology. 1984;137:255–265. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mundry K.W., Watkins P.A., Wilson T.M. Complete uncoating of the 5′ leader sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA occurs rapidly and is required to initiate cotranslational virus disassembly in vitro. J. Gen. Virol. 1991;72:769–777. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-4-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Culver J.N., Dawson W.O., Stubbs G. Site-directed mutagenesis confirms the involvement of carboxylate groups in the disassembly of tobacco mosaic virus. Virology. 1995;206:724–730. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw J.G. Tobacco mosaic virus and the study of early events in virus infections. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1999;354:603–611. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen N., Tilsner J., Oparka K. The 5′ cap of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is required for virion attachment to the actin/endoplasmic reticulum network during early infection. Traffic. 2009;10:536–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florin E.L., Moy V.T., Gaub H.E. Adhesion forces between individual ligand-receptor pairs. Science. 1994;264:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.8153628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinterdorfer P., Baumgartner W., Schindler H. Detection and localization of individual antibody-antigen recognition events by atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:3477–3481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rief M., Clausen-Schaumann H., Gaub H.E. Sequence-dependent mechanics of single DNA molecules. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1999;6:346–349. doi: 10.1038/7582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu N.N., Bu T.J., Li H. The nature of the force-induced conformation transition of dsDNA studied by using single molecule force spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2010;26:9491–9496. doi: 10.1021/la100037z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rief M., Gautel M., Gaub H.E. Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science. 1997;276:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W.K., Machón C., Soultanas P. Single-molecule atomic force spectroscopy reveals that DnaD forms scaffolds and enhances duplex melting. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:706–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claridge S.A., Schwartz J.J., Weiss P.S. Electrons, photons, and force: quantitative single-molecule measurements from physics to biology. ACS Nano. 2011;5:693–729. doi: 10.1021/nn103298x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C.J., Jiang Z.H., Wang S. Intercalation interactions between dsDNA and acridine studied by single molecule force spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2007;23:9140–9142. doi: 10.1021/la7013804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clausen-Schaumann H., Seitz M., Gaub H.E. Force spectroscopy with single bio-molecules. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2000;4:524–530. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugel T., Seitz M. The study of molecular interactions by AFM force spectroscopy. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2001;22:989–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janshoff A., Neitzert M., Fuchs H. Force spectroscopy of molecular systems—single molecule spectroscopy of polymers and biomolecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2000;39:3212–3237. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000915)39:18<3212::aid-anie3212>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang W.K., Zhang X. Single molecule mechanochemistry of macromolecules. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2003;28:1271–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller D.J., Dufrêne Y.F. Atomic force microscopy as a multifunctional molecular toolbox in nanobiotechnology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008;3:261–269. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinterdorfer P., Dufrêne Y.F. Detection and localization of single molecular recognition events using atomic force microscopy. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nmeth871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Müller D.J., Helenius J., Dufrêne Y.F. Force probing surfaces of living cells to molecular resolution. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:383–390. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhuang X.W., Rief M. Single-molecule folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:88–97. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allison D.P., Hinterdorfer P., Han W.H. Biomolecular force measurements and the atomic force microscope. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Q.M., Lu Z.Y., Marszalek P.E. Direct detection of the formation of V-amylose helix by single molecule force spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9387–9393. doi: 10.1021/ja057693+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giannotti M.I., Vancso G.J. Interrogation of single synthetic polymer chains and polysaccharides by AFM-based force spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem. 2007;8:2290–2307. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200700175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X., Liu C.J., Wang Z.Q. Force spectroscopy of polymers: studying on intramolecular and intermolecular interactions in single molecular level. Polymer (Guildf.) 2008;49:3353–3361. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H.B., Cao Y. Protein mechanics: from single molecules to functional biomaterials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:1331–1341. doi: 10.1021/ar100057a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang W., Kou X.L., Zhang W.K. Recent progress in single-molecule force spectroscopy study of polymers. Chem. J. Chinese U. 2012;33:861–875. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu N.N., Zhang W.K. Feeling inter- or intramolecular interactions with the polymer chain as probe: recent progress in SMFS studies on macromolecular interactions. ChemPhysChem. 2012;13:2238–2256. doi: 10.1002/cphc.201200154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu N.N., Peng B., Shen J.C. Pulling genetic RNA out of tobacco mosaic virus using single-molecule force spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11036–11038. doi: 10.1021/ja1052544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu K., Song Y., Zhang X. Extracting a single polyethylene oxide chain from a single crystal by a combination of atomic force microscopy imaging and single-molecule force spectroscopy: toward the investigation of molecular interactions in their condensed states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:3226–3229. doi: 10.1021/ja108022h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francius G., Lebeer S., Dufrêne Y.F. Detection, localization, and conformational analysis of single polysaccharide molecules on live bacteria. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1921–1929. doi: 10.1021/nn800341b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dupres V., Verbelen C., Dufrêne Y.F. Force spectroscopy of the interaction between mycobacterial adhesins and heparan sulphate proteoglycan receptors. ChemPhysChem. 2009;10:1672–1675. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rankl C., Kienberger F., Hinterdorfer P. Multiple receptors involved in human rhinovirus attachment to live cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17778–17783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806451105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hao X., Shang X., Wang H.D. Single-particle tracking of hepatitis B virus-like vesicle entry into cells. Small. 2011;7:1212–1218. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hao X., Wu J.Z., Wang H.D. Caveolae-mediated endocytosis of biocompatible gold nanoparticles in living HeLa cells. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2012;24:164207. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/24/16/164207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans E. Energy landscapes of biomolecular adhesion and receptor anchoring at interfaces explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Faraday Discuss. 1998;111:1–16. doi: 10.1039/a809884k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Merkel R., Nassoy P., Evans E. Energy landscapes of receptor-ligand bonds explored with dynamic force spectroscopy. Nature. 1999;397:50–53. doi: 10.1038/16219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang W., Lü X., Shen J.C. EMSA and single-molecule force spectroscopy study of interactions between Bacillus subtilis single-stranded DNA-binding protein and single-stranded DNA. Langmuir. 2011;27:15008–15015. doi: 10.1021/la203752y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morfill J., Kühner F., Gaub H.E. B-S transition in short oligonucleotides. Biophys. J. 2007;93:2400–2409. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.106112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dietz H., Rief M. Exploring the energy landscape of GFP by single-molecule mechanical experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16192–16197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404549101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Best R.B., Fowler S.B., Clarke J. A simple method for probing the mechanical unfolding pathway of proteins in detail. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12143–12148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192351899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evans E.A., Calderwood D.A. Forces and bond dynamics in cell adhesion. Science. 2007;316:1148–1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1137592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niu Z.W., Bruckman M.A., Wang Q. Assembly of tobacco mosaic virus into fibrous and macroscopic bundled arrays mediated by surface aniline polymerization. Langmuir. 2007;23:6719–6724. doi: 10.1021/la070096b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Royston E., Ghosh A., Culver J.N. Self-assembly of virus-structured high surface area nanomaterials and their application as battery electrodes. Langmuir. 2008;24:906–912. doi: 10.1021/la7016424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang W.K., Barbagallo R., Allen S. Progressing single biomolecule force spectroscopy measurements for the screening of DNA binding agents. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:2325–2333. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Florin E.L., Rief M., Gaub H.E. Sensing specific molecular interactions with the atomic force microscope. Biosens. Bioelectron. 1995;10:895–901. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butt H.J., Jaschke M. Calculation of thermal noise in atomic force microscopy. Nanotechnology. 1995;6:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kerssemakers J.W.J., Munteanu E.L., Dogterom M. Assembly dynamics of microtubules at molecular resolution. Nature. 2006;442:709–712. doi: 10.1038/nature04928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steckert J.J., Schuster T.M. Sequence specificity of trinucleoside diphosphate binding to polymerized tobacco mosaic virus protein. Nature. 1982;299:32–36. doi: 10.1038/299032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rief M., Fernandez J.M., Gaub H.E. Elastically coupled two-level systems as a model for biopolymer extensibility. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998;81:4764–4767. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bell G.I. Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science. 1978;200:618–627. doi: 10.1126/science.347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans E., Ritchie K. Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1541–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan C.B., Chen A., Moy V.T. Energy landscape of streptavidin-biotin complexes measured by atomic force microscopy. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10219–10223. doi: 10.1021/bi992715o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Odrowaz Piramowicz M., Czuba P., Szymoński M. Dynamic force measurements of avidin-biotin and streptavidin-biotin interactions using AFM. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2006;53:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Teulon J.M., Delcuze Y., Pellequer J.L. Single and multiple bonds in (strept)avidin-biotin interactions. J. Mol. Recognit. 2011;24:490–502. doi: 10.1002/jmr.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Friddle R.W., Noy A., De Yoreo J.J. Interpreting the widespread nonlinear force spectra of intermolecular bonds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13573–13578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202946109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ge P., Zhou Z.H. Hydrogen-bonding networks and RNA bases revealed by cryo electron microscopy suggest a triggering mechanism for calcium switches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9637–9642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018104108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goelet P., Lomonossoff G.P., Karn J. Nucleotide sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:5818–5822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vanzi F., Takagi Y., Goldman Y.E. Mechanical studies of single ribosome/mRNA complexes. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1909–1919. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.056283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oberhauser A.F., Hansma P.K., Fernandez J.M. Stepwise unfolding of titin under force-clamp atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:468–472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021321798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernandez J.M., Li H.B. Force-clamp spectroscopy monitors the folding trajectory of a single protein. Science. 2004;303:1674–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.1092497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alegre-Cebollada J., Kosuri P., Fernández J.M. Direct observation of disulfide isomerization in a single protein. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:882–887. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.