Abstract

Ability to self-regulate varies and self-regulatory strength is a limited source that can be depleted or fatigued. Research on the impact of individual differences on self-regulatory capacity is still scarce, and this study aimed to examine whether personality factors such as dispositional optimism, conscientiousness, and self-consciousness can impact or buffer self-regulatory fatigue. Participants were patients diagnosed with chronic multi-symptom illnesses (N = 50), or pain free matched controls (N = 50), randomly assigned to either a high or low self-regulation task, followed by a persistence task. Higher optimism predicted longer persistence (p = .04), and there was a trend towards the same effect for conscientiousness (p = .08). The optimism by self-regulation interaction was significant (p = .01), but rather than persisting despite self-regulatory effort, optimists persisted longer only when not experiencing self-regulatory fatigue. The effects of optimism were stronger for controls than patients. There was also a trend towards a similar conscientiousness by self-regulation interaction (p = .06). These results suggest that the well-established positive impact of optimism and conscientiousness on engagement and persistence may be diminished or reversed in the presence of self-regulatory effort or fatigue, adding an important new chapter to the self-regulation, personality, and pain literature.

Keywords: Self-regulation, Self-regulatory fatigue, Dispositional optimism, Conscientiousness, Selfconsciousness

1. Introduction

People vary in the way they approach and cope with difficult and challenging situations, and individual differences could potentially impact ability to self-regulate (Hagger, Wood, Stiff, & Chatzisarantis, 2010; Hoyle, 2006). Research on the impact of individual differences on self-regulatory capacity is in its infancy, and the current study sought to examine whether personality factors such as optimism, conscientiousness, and self-consciousness can influence, perhaps even buffer, impact of self-regulatory effort. Self-regulatory capacity may also play a role in chronic multi-symptom illnesses (CMI; Solberg Nes, Carlson, Crofford, de Leeuw, & Segerstrom, 2010; Solberg Nes, Roach, & Segerstrom, 2009), and the current study also sought to examine the role of individual differences, in the face of self-regulatory effort, for patients with CMI compared with pain free controls.

1.1. Self-regulation and individual differences

Self-regulation involves any effort to control internal or external, mental or physical, activities (Carver & Scheier, 1998). Ability to self-regulate varies, however, and research has shown self-regulatory efforts such as having to control thoughts, impulses, and emotions to be associated with decreased persistence on subsequent tasks, an effect known as ego depletion (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven, & Tice, 1998) or self-regulatory fatigue (SRF). The strength model hypothesis proposes that exercising self-control depends on a common resource, which again is limited and may become depleted or fatigued, almost like a muscle (Baumeister, Vohs, & Tice, 2007; Baumeister et al., 1998). Examining the effect of depletion on task performance and outcomes in 82 separate studies, a recent meta analysis found support for the depletion effect and strength model hypothesis, but suggested that alternative explanations such as lack of motivation, fatigue, and negative affect may also play a role (Hagger et al., 2010). This indicates a need for further explorations of the potential underlying mechanisms of the SRF effect.

Fatigue of self-regulatory resources may moderate trait effects on behavior (Baumeister, Gailliot, DeWall, & Oaten, 2006), and individual differences such as personality could potentially influence self-regulatory effort or capacity (Hoyle, 2006). In fact, personality traits such as optimism, conscientiousness, and self-consciousness often impact how people deal with challenges, approach tasks, goals, and stressors (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Costa & McCrae, 1992), and could also play an important role in the mechanisms of self-regulation.

1.1.1. Dispositional optimism

Optimism has been positively associated with approach coping strategies aiming to manage stressors, and negatively associated with avoidance coping strategies aiming to avoid stressors (Solberg Nes & Segerstrom, 2006). Optimists see positive outcomes as attainable, and are subsequently more likely to invest continued effort in order to achieve their goals (Carver, Blaney, & Scheier, 1979; Solberg Nes, Segerstrom, & Sephton, 2005). This type of behavior may also impact how optimists cope with self-regulatory demands. For example, in a study examining pursuit of personal goals in female patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS), optimistic patients were less likely to decrease engagement or give up on goals, even on difficult days (Affleck et al., 2001), suggesting that optimists may persist longer in situations requiring self-regulatory effort, perhaps despite SRF.

1.1.2. Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness represents thoroughness and self-discipline, and is associated with striving towards achievement (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Conscientiousness has been linked with use of problem focused coping (Bartley & Roesch, 2011), and facets of conscientiousness (i.e., competence/self-efficacy, orderliness, dutifulness, achievement striving, self-discipline, and deliberation/cautiousness) seem to play a role in prediction of behavior (Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). These facets may also predict approach coping and persistence in the face of self-regulatory effort or fatigue.

1.1.3. Self-consciousness

Self-consciousness represents an acute sense of self-awareness and preoccupation with oneself (Lipka & Brinthaupt, 1992), and can be private, with focus on own feelings and self, or public, with focus on how others may see oneself (Fenigstein, Scheier, & Buss, 1975). Self-consciousness tends to focus a person on his or her goal directed behavior, may impact persistence on challenging tasks, either by itself or in interaction with expectancies (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Solberg Nes et al., 2005), and has even been seen to enhance effects of self-regulatory activities (Carver et al., 1979). Aiming to contribute to a better understanding of the underlying factors of self-regulatory capacity, the current study sought to explore the potential impact of optimism, conscientiousness, and self-consciousness on SRF.

1.2. Self-regulation and chronic multi-symptom illnesses

Chronic multi-symptom illnesses (CMI) such as FMS and temporomandibular disorders (TMD) present with an abundance of physical and psychological challenges (see Solberg Nes et al. (2009) for a review). Adaptation to such challenges may fatigue or exhaust self-regulatory resources, and CMI may be intertwined with SRF. For example, a large number of patients with CMI experience psychological distress, worry and ruminate about their health and future, report interpersonal distress, and often engage in passive coping strategies aiming to avoid or disengage from unpleasant activities (Solberg Nes et al., 2009). All of these behaviors and symptoms may require self-regulatory effort, or be indicators of SRF.

We recently carried out a study examining the concept of SRF in patients diagnosed with FMS or TMD (Solberg Nes et al., 2010). Participants were assigned to either a high or low self-regulation task (i.e., a task requiring self-regulatory effort), followed by a persistence task (i.e., anagram task). High self-regulatory effort was associated with lower persistence on the subsequent task, supporting the SRF hypothesis (Baumeister et al., 1998), and patients displayed significantly less persistence than matched pain free controls. In fact, low self-regulatory effort for patients was associated with similar low persistence as patients and controls exerting high self-regulatory effort, suggesting that patients with CMI may in fact suffer from chronic SRF (Solberg Nes et al., 2010).

1.3. Current study

In the current investigation, we carried out additional analyses of the sample from Solberg Nes et al. (2010), seeking to examine the potential impact of dispositional optimism, conscientiousness and self-consciousness on self-regulatory capacity. It was hypothesized that individual differences in personality would predict persistence (i.e., time spent on the first, unsolvable, anagram) such that high optimism, conscientiousness, or self-consciousness would be associated with longer persistence. Patients, potentially already experiencing SRF (Solberg Nes et al., 2010), were expected to benefit less from optimism, conscientiousness and self-consciousness than pain free controls.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Details of methods and procedures for this study have been reported elsewhere (Solberg Nes et al., 2010). Briefly, participants were female patients (N = 50) diagnosed with FMS, TMD, or both, and healthy matched controls (N = 50). The original study included only females in order to avoid potential confounds from gender differences (e.g., physiological measures). All participants were between the ages 25 and 56 years old (mean = 42.8; standard deviation (SD) = 8.9), majority Caucasian (90%), and received $50 for study completion.

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Self-regulation and persistence tasks

Participants were randomly assigned to either a high (N = 50) or low (N = 50) self-regulation condition. In the self-regulation task, all participants watched a brief video clip without sound featuring a female being interviewed by an off-camera individual (Gilbert, Krull, & Pelham, 1988; Schmeichel, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2003). Participants in the high self-regulation condition were asked not to read or look at any words that might appear on the screen. During the interview, a series of one-syllable words (e.g., jump) were shown for 10 s each in the bottom right corner of the screen. Participants then completed an anagram (persistence) task (Solberg Nes et al., 2005, 2010). The task contains 11 anagrams, the first of which is unsolvable (GGAWIL), and the remaining 10 are moderate to difficult but solvable.

2.3. Psychological measures

2.3.1. Background variables

Participants reported their age, race, years of education, and annual family income.

2.3.2. Current activity appraisal (manipulation check)

Following each experimental task the participants completed a form containing six Likert-type questions related to the activity they just finished (i.e., “It was difficult,” “It was stressful,” “It made me tired,” “It required a lot of effort,” “I had to concentrate on the task,” “I had to force myself to keep going,” “I wanted to stop before it was over”). Alpha reliability for the six items was .93 following a self-regulation task, and .81 following an anagram task (Segerstrom & Solberg Nes, 2007). For the self-regulation task we also included two attention specific questions (i.e., “How difficult was it to follow the instructions for watching the video clip?” and “How difficult was it to control your attention in order to follow the instructions when watching the video clip?”). Univariate ANOVAS showed the manipulations were effective, as participants in the high self-regulation condition rated the self-regulation task as much more demanding than participants in the low condition, F(1, 99) = 8.60, p = .001. There was minimal difference between participants in the high or low self-regulation condition on perception of how difficult the anagram task was, F(1, 99) = 2.71, p = .11, but patients rated this task as more demanding than controls, F(1, 99) = 4.28, p = .04 (see Solberg Nes et al. (2010) for more details).

2.3.3. Dispositional optimism: life orientation test-revised (LOT-R)

The LOT-R (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) is a 10-item measure of generalized positive outcome expectancies. Three items are phrased positively (e.g., “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”), three negatively (e.g., “If something can go wrong for me it will”), and four are filler items. The LOT-R has acceptable internal consistency (.78) and construct validity with regard to related constructs (Scheier et al., 1994). In the current study α = .82.

2.3.4. Conscientiousness: NEO-FFI

The NEO-FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1992) is a 60-item general measure of personality reflecting neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. Participants indicated on a 5-point scale the degree to which items describe them. The NEO-FFI has adequate psychometric properties, with internal consistency ranging from .68 to .86, test-retest reliability from .86 to .90, and overall well established reliability and validity (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzesniewski, 2001). For conscientiousness in the current study α = .78.

2.3.5. Self-consciousness

The self-consciousness scale (Fenigstein et al., 1975). This is a widely used 17-item measure of public and private self-consciousness that has demonstrated construct validity in a variety of contexts (Carver & Glass, 1976; Fenigstein et al., 1975). Test–retest correlations for the public self-consciousness sub-scale = .84, and for private self-consciousness = .79 (Fenigstein et al., 1975). In the current study α = .78.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Independent sample t-tests examined whether any significant differences existed between the groups related to demographics and personality. Univariate ANOVAs examined the effect of self-regulatory effort on persistence, and multiple linear hierarchical regressions examined the impact of personality variables on persistence. Significant interaction effects were plotted for values one SD above and below the mean of each predictor (Aiken & West, 1991). Continuous variables were centered around zero before analysis to reduce collinearity between main effects and interactions. The study used the standard alpha level of .05 for all main statistical analyses.

2.5. Power analyses

Number of participants (n) needed to reach power of .80 was calculated for α = .05, two-tailed. Main effect power was computed using seven studies involving identical or similar attention- or thought-control manipulations, showing n = 44−46 participants (n per group =11) needed to detect power = .80. Interaction effect power was computed using four studies employing attention- or thought control fatigue by motivation or provocation interactions, showing n = 84 (n per group = 21) needed to detect power = .80. We conservatively included n = 100 (n per group = 25) which estimates power = .92 to detect effect size of η = .30 and power = .99 to detect effect size of η = .40 (see also Solberg Nes et al., 2010).

3. Results

No significant differences were found in the high vs. low self-regulation or patient vs. control groups on age, years of education, or average annual income. There were no significant differences between participants in the high vs. low self-regulation groups on optimism, t(98) = .53, p = .60, conscientiousness, t(98) = 1.32, p = .19, or self-consciousness, t(98) = .42, p = .68. There were, however, significant differences between patients and controls on optimism, t(98) = 3.14, p = .01 and conscientiousness t(98) = 4.06, p<.001, but not on self-consciousness t(98) = .66, p = .51 (Table 1). Optimism and conscientiousness correlated significantly (r = .29, p < .01), but self-consciousness did neither correlate significantly with optimism (r = −.15) nor conscientiousness (r = .09).

Table 1.

Group differences in personality.

| Patient vs. control | High vs. low self-regulation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Mean | t(98) | p | Mean | t(98) | p | |||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Patients | Controls | High SR | Low SR | |||||

| Dispositional optimism | 3.48 | 4.04 | 3.14 | =.01 | 3.77 | 3.85 | .53 | =.60 |

| Conscientiousness | 3.23 | 3.97 | 4.06 | <.001 | 3.75 | 3.88 | 1.32 | =.19 |

| Self-consciousness | 3.24 | 3.31 | .66 | =.51 | 3.26 | 3.30 | .42 | =.68 |

3.1. Individual differences, self-regulatory demand, and persistence

3.1.1. Optimism

There was a main effect of dispositional optimism on persistence, such that the more optimistic participants were, the longer they persisted on the unsolvable anagram, β = .19, t = 2.10, p = .03. This was still the case after controlling for self-regulation condition, β = .29, t = 3.30, p = .01, but not after controlling for patient vs. control group, β = .09, t=.90, p = .37. Optimists in the high self-regulatory condition were expected to experience SRF but were, due to a belief in positive outcomes, expected to persist longer than pessimists. There was a significant optimism by self-regulation interaction, R2Δ = .05, FΔ(1, 96) = 6.64, β = −.31, t =−2.58, p = .01. However, the interaction took a different form than predicted. Optimists, compared with pessimists, persisted longer on a difficult task only when not experiencing SRF (see Fig. 1). In the high self-regulatory condition, optimism did not attenuate the impact of high self-regulation on persistence, but instead appeared to have a negative effect on persistence.

Fig. 1.

Impact of optimism by self-regulation on persistence.

The optimism by patient/control group interaction was not significant R2Δ = .01, FΔ(1, 96) = 1.27, β = −.18, t = −1.13, p = .26. However, the optimism by self-regulation 2-way interaction may be qualified by an optimism by self-regulation by illness 3-way interaction that nearly reached statistical significance, R2Δ = .02, FΔ(1, 93) = 3.26, β = .36, p = .07. The interaction is best understood as differing effects of having low (−1 SD) vs. high (+1 SD) optimism across groups (Aiken & West, 1991). The effect of optimism was largest in the controls without SRF, where high optimism predicted longer persistence, and controls with SRF, where high optimism predicted shorter persistence (see Fig. 2). Similarly, but with smaller effects, high optimism in patients without SRF predicted longer persistence, whereas high optimism in patients with SRF predicted shorter persistence.

Fig. 2.

Optimism by illness by self-regulation interaction.

As patients reported lower optimism at baseline compared with controls, we also examined the two groups separately. Controls: There was no main effect of optimism on persistence in the control group alone, β = .16, t = 1.13, p = .26, but the optimism by self-regulation interaction was significant, R2Δ = .06, FΔ(1, 46) = 4.39, β = −.33, t = −2.09, p = .04. Patients: There was no main effect of optimism on persistence in the patient group alone, β = .02, t = .14, p = .89, and no significant optimism by self-regulation interaction, R2Δ = .03, FΔ(1, 46) = 1.62, β = −.25, t =−1.27, p = .21. Examining the beta weights in the 3-way interaction that almost reached significance for the entire sample, the optimism by self-regulation interaction yielded the largest effect, β = −.54, t = −2.76, p < .01, optimism by pain had less impact, β = −.31, t = −1.65, p = .10, and pain by self-regulation yielded the smallest effect, β = .15, t = 1.16, p = .25.

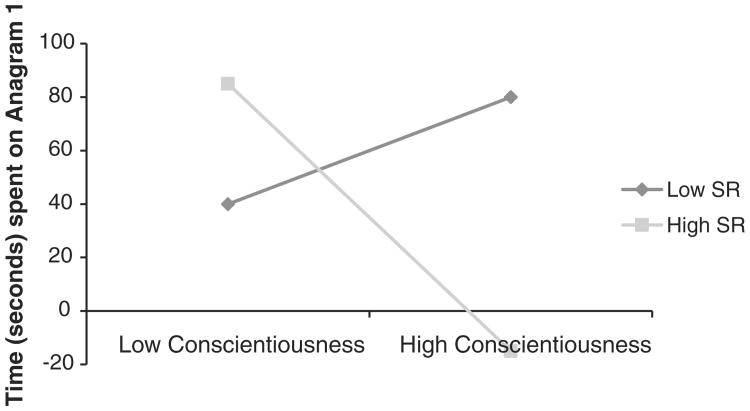

3.1.2. Conscientiousness

There was a trend towards a main effect of conscientiousness on persistence, such that the more conscientious participants were the longer they persisted on the unsolvable anagram task, β = .18, t = 1.78, p = .08. However, after controlling for self-regulation condition, β = .13, t = 1.36, p = .18, and particularly after controlling for patient vs. control group condition, β = .01, t = .08, p = .93, this was no longer the case.

There was also a trend towards a conscientiousness by self-regulation interaction, R2Δ = .03, FΔ(1, 96) = 3.74, β = −.33, p = .06. However, as with optimism, the trend took a somewhat different form than predicted, as the impact of conscientiousness on persistence diminished when combined with high self-regulatory demand. Conscientious participants, compared with less conscientious participants, persisted longer on the difficult anagram task only when not experiencing SRF (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Impact of conscientiousness by self-regulation on persistence.

There was no significant conscientiousness by patient vs. control interaction, R2Δ = .00, FΔ(1, 96) = .09, β = −.06, t = −.31, p = .76, and the conscientiousness by self-regulation by illness relationship did not reach significance, R2Δ = .01, FΔ(1, 93) = .76, β = −.19, t = −.87, p = .38. There was no significant impact of conscientiousness on persistence either alone or in interaction with self-regulation when separating analyses on patient vs. control group.

3.1.3. Self-consciousness

There was no impact of self-consciousness on persistence, β = −.03, t = −.31, p = .75, and no significant self-consciousness by self-regulation, R2Δ = .00, FΔ(1, 96) = .09, β = −.04, t = −.30, p = .77, or patient vs. control, R2Δ = .01, FΔ(1, 96) = 1.64, β = .19, t=1.28, p = .20, interactions in the current study. Similarly, the self-consciousness by self-regulation by illness relationship did not reach significance, R2Δ = .00, FΔ(1, 93) = .84, β = −.18, t = −.92, p = .36.

4. Discussion

Recent research has suggested that individual differences may play an important role in the self-regulation paradigm (Baumeister et al., 2006; Hoyle, 2006). The current study aimed to show that personality traits such as dispositional optimism, conscientiousness, and self-consciousness may buffer or diminish the negative impact of SRF, and that this would be more the case for healthy adults than for patients with CMI. Results, however, indicate that the effect of individual differences in the face of self-regulatory effort and fatigue is more complex than predicted.

Supporting previous research (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Solberg Nes et al., 2005), higher dispositional optimism predicted longer persistence. Rather than persisting despite SRF, as expected, however, optimists persisted longer on a difficult task only when not experiencing SRF (see Figs. 1 and 2). The effect of optimism was largest for controls without SRF, where high optimism predicted longer persistence, and controls with SRF, where high optimism predicted shorter persistence. This indicates that the positive impact of optimism on engagement and persistence may in fact be diminished or reversed in the presence of SRF, and suggests that patients with CMI may benefit significantly less from the potentially positive impact of optimism.

Research suggests that self-regulatory performance is related not only to how much self-control participants have recently exerted, but also to how much effort or control they expect to exert next (Hagger et al., 2010). When exerting self-regulatory effort, and expecting to exert more in the near future, participants performed worse on tests of self-control than those who did not recently exert self-control or did not expect to do so (Muraven, Shmueli, & Burkley, 2006; Tyler & Burns, 2009). A similar negative effect of optimism on persistence has previously been seen when the same anagram task appeared to conflict with high expectations of ability to perform (Solberg Nes et al., 2005). Previous research has also shown optimistic persistence in goal pursuit to be linked to higher goal conflict, as optimists are more likely to persist at numerous goals at once, perhaps leading to goal conflict in the short term, but higher likelihood of goal achievement in the long run (Segerstrom & Solberg Nes, 2006). It is possible that optimists in the current study, after having exerted high self-regulatory effort, attempted to conserve self-regulatory resources, perhaps expecting to engage in more goals after leaving the study, and as a consequence were more likely to exhibit effects of SRF. Optimists in the low self-regulatory condition did not have to exert self-control, and hence had more resources available for the persistence task.

Supporting the idea that CMI may be intertwined with SRF (Solberg Nes et al., 2009, 2010), the effects of optimism were weaker for patients than for controls. In fact, when testing patients and controls separately, only the interaction for the control group reached significance. Patients high in optimism persisted longer on the anagram task only when not first exposed to self-regulatory effort (see Fig. 2). This suggests that patients with CMI may actually be poor at regulating their effort both under conditions that typically call for more effort, and under conditions that might call for conservation. Patients also differed from controls in their reported degree of optimism and conscientiousness, perhaps indicating that SRF and/or CMI may take their toll on positive traits, or at least on the potential benefit from such.

As predicted, conscientious participants tended to persist longer on the anagram task, and there was a trend towards a conscientiousness by self-regulation interaction on persistence. As with optimism, however, the impact of conscientiousness on persistence diminished when combined with high self-regulatory demand, and conscientious participants persisted longer on the anagram task only when not experiencing SRF (see Fig. 3). Some of the same functions as suggested for the optimism interactions may again apply here. Rather than persisting on the second task as a consequence or asset of their personality trait, conscientious participants may have attempted to conserve energy for expected upcoming tasks, and hence showed stronger effects of SRF. Conscientious and optimistic people likely have both high ability and high demands, and expectancy of future demands (i.e., conservation for future demands), may have “won out” over the need or wish for persistence or performance in the current study. Patients again appeared to have less positive impact from the personality trait than their pain free colleagues.

Self-consciousness tends to focus a person on his or her goal directed behavior, and has been seen to enhance effects of self-regulatory activities (Carver et al., 1979). There was no support for any link between self-consciousness, self-regulation, and persistence in the current study, however, and the role of self-consciousness in engagement and self-regulatory processes may have to be reconsidered.

Even though power analysis indicated adequate power for detecting main effects and interactions, it is possible that this study is underpowered for detecting 3-way interactions, and future replications are needed. As noted, there was a baseline difference in level of dispositional optimism and conscientiousness in patients vs. controls, with patients reporting lower optimism and conscientiousness than controls. It is unclear whether this is representative of individual differences in patients suffering from CMI, but this issue should be further examined. This is one of the first studies to examine the impact of individual differences on self-regulatory effort or fatigue, and to our knowledge the first study to examine links among personality, self-regulation, and CMI. Future research is needed to replicate and further explore these apparently complex relationships.

Capacity to self-regulate varies, and the current study aimed to show that individual differences in personality can impact, and perhaps even buffer, the often negative effect of self-regulatory effort. As seen, optimism and conscientiousness predicted persistence, but were only beneficial for ability to persist when not combined with high self-regulatory effort. This suggests that the well established positive impact of optimism and conscientiousness on engagement and persistence may be diminished or even reversed in the presence of SRF, perhaps indicating a focus on conserving effort rather than overcoming SRF. The study also suggests that patients suffering from CMI may have even less benefit from these traits than healthy controls, perhaps due to chronic SRF, adding a whole new chapter to the personality, self-regulation, and chronic pain, literature.

References

- Affleck G, Tennen H, Zautra A, Urrows S, Abeles M, Karoly P. Women's pursuit of personal goals in daily life with fibromyalgia: A valueexpectancy analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:587–596. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley CE, Roesch SC. Coping with daily stress: The role of conscientiousness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Muraven M, Tice DM. Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1252–1265. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Gailliot M, DeWall CN, Oaten M. Self-regulation and personality: How interventions increase regulatory success, and how depletion moderates the effects of trait on behavior. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1773–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Blaney PH, Scheier MF. Reassertion and giving up: The interactive role of self-directed attention and outcome expectancy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37:1859–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Glass DC. The self-consciousness scale: A discriminant validity study. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1976;40:169–172. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4002_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein A, Scheier MF, Buss AH. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1975;43:522–527. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT, Krull DS, Pelham BW. Of thoughts unspoken: Social inference and the self-regulation of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:685–694. [Google Scholar]

- Hagger M, Wood C, Stiff C, Chatzisarantis NL. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:495–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH. Personality and self-regulation: Trait and information-processing perspectives. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1507–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipka RP, Brinthaupt TM. Self-perspectives across the life span. SUNY Press; 1992. p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M, Shmueli D, Burkley E. Conserving self-control strength. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:524–537. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunonen SV, Ashton MC. Big Five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:524–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Fraley RC, Roberts BW, Trzesniewski KH. A longitudinal study of personality change in young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:617–640. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeichel BJ, Vohs KD, Baumeister RF. Intellectual performance and ego depletion: Role of the self in logical reasoning and other information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:33–46. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Solberg Nes L. When goals conflict but people prosper: The case of dispositional optimism. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:576–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Solberg Nes L. Heart rate variability indexes self-regulatory strength, exercise, and depletion. Psychology Science. 2007;18:275–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg Nes L, Carlson CR, Crofford LJ, de Leeuw R, Segerstrom SC. Self-regulatory deficits in Fibromyalgia and Temporomandibular disorders. Pain. 2010;151:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg Nes L, Roach AR, Segerstrom SC. Executive functions, self-regulation, and chronic pain: A review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;37:173–183. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg Nes L, Segerstrom SC. Dispositional optimism and coping: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2006;10:235–251. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg Nes L, Segerstrom SC, Sephton SE. Engagement and arousal: Optimism's effects during a brief stressor. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:111–120. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler JM, Burns KC. Triggering conservation of the self's regulatory resources. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2009;31:255–266. [Google Scholar]