Abstract

Decreased lung vascular growth and pulmonary hypertension contribute to poor outcomes in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH). Mechanisms that impair angiogenesis in CDH are poorly understood. We hypothesize that decreased vessel growth in CDH is caused by pulmonary artery endothelial cell (PAEC) dysfunction with loss of a highly proliferative population of PAECs (HP-PAEC). PAECs were harvested from near-term fetal sheep that underwent surgical disruption of the diaphragm at 60–70 days gestational age. Highly proliferative potential was measured via single cell assay. PAEC function was assessed by assays of growth and tube formation and response to known proangiogenic stimuli, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and nitric oxide (NO). Western blot analysis was used to measure content of angiogenic proteins, and superoxide production was assessed. By single cell assay, the proportion of HP-PAEC with growth of >1,000 cells was markedly reduced in the CDH PAEC, from 29% (controls) to 1% (CDH) (P < 0.0001). Compared with controls, CDH PAEC growth and tube formation were decreased by 31% (P = 0.012) and 54% (P < 0.001), respectively. VEGF and NO treatments increased CDH PAEC growth and tube formation. VEGF and VEGF-R2 proteins were increased in CDH PAEC; however, eNOS and extracellular superoxide dismutase proteins were decreased by 29 and 88%, respectively. We conclude that surgically induced CDH in fetal sheep causes endothelial dysfunction and marked reduction of the HP-PAEC population. We speculate that this CDH PAEC phenotype contributes to impaired vascular growth in CDH.

Keywords: lung development, lung hypoplasia, angiogenesis

congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is caused by disruption of normal diaphragm development allowing herniation of the abdominal viscera in the thoracic cavity, which leads to lung hypoplasia and severe respiratory distress shortly after birth (35). Despite improvements in the clinical care of infants with CDH, the overall mortality remains significant (39). Two major determinants of outcome in infants with CDH are the degree of lung hypoplasia and the severity of pulmonary hypertension (11, 35, 38, 40, 42), which are both related to abnormalities in pulmonary vascular growth and structure. Pulmonary vascular disease in CDH includes decreased pulmonary arterial number, increased muscularization in the arterial wall, and abnormal adventitial thickening, which all contribute to severe hypoxemia and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (9).

A large animal model of CDH induced by the surgical creation of a diaphragmatic defect with placement of the abdominal contents in the chest of fetal sheep near midgestation has been used for many years to study the physiological effects of this disease (10, 15, 21, 36, 41, 43). Past studies have shown that this surgical CDH animal model disrupts lung growth and results in lung histopathology that is similar to human CDH, including a decrease in vessel density and increased muscularization of pulmonary arteries (1). The severity of lung disease in this sheep model is related to the timing of the surgical intervention, since the degree of lung hypoplasia is worse when the defect is induced early during gestation (8). Despite extensive use of this model for exploring innovative surgical techniques, little is known about basic mechanisms responsible for the described changes in lung vascular growth and structure. Additionally, studies examining cellular mechanisms underlying the pathobiology of CDH through in vitro studies of isolated pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) from this sheep model have not been previously performed.

Recent observations have shown that populations of highly proliferative endothelial cells (HP-PAEC) with a complete hierarchy of endothelial cells can exist within vascular walls (18). Zengin et al. showed that there is a distinct zone of the vascular wall that contains endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs). These cells can give rise to mature endothelial cells, as well as hematopoietic and immune cells (45). Similarly, Alvarez et al. demonstrated that the lung microvasculature is enriched with resident progenitor cells that exhibit vasculogenic capacity (3). Angiogenic cells with highly proliferative potential may be important in normal lung development or in lung repair after injury. Although endothelial colony-forming cell-like, proangiogenic cells have been previously described in the developing lung (6, 12), HP-PAEC as a subpopulation of endothelial cells within proximal vessels in the developing lung have not been previously shown. Furthermore, whether impaired vascular growth in CDH is related to a decrease in this population of HP-PAECs is unknown.

Therefore, we hypothesize that pulmonary vascular disease in CDH is the result of the loss of a HP-PAEC within the vascular wall with endothelial cell dysfunction, which is characterized by impaired angiogenesis with decreased nitric oxide (NO) production or bioavailability. To test these hypotheses, we performed a series of in vitro experiments with isolated PAEC from fetal sheep with experimental CDH and controls. We report that PAEC from CDH sheep have an abnormal phenotype in vitro, which includes a marked decrease in the population of HP-PAEC in pulmonary arteries compared with control sheep, as well as decreased endothelial cell growth and decreased tube formation.

METHODS

Experimental model of CDH.

Pregnant, mixed-breed (Colombia-Rambouillet) ewes were used in this study. All procedures and protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center and followed the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals established by the National Research Council. Surgery was performed at 60–70 days gestation (full term = 147 days) after ewes had fasted for 24 h. Animals were given intramuscular penicillin G (600,000 U) and gentamicin (80 mg) immediately before surgery. Ewes were sedated with intravenous ketamine (8 ml) and diazepam (2 ml) and intubated and ventilated with 1–2% isoflurane for the duration of surgery. Under sterile conditions, a midline abdominal incision was made, and the uterus was externalized. A hysterotomy was made, and the left fetal forelimb was exposed. A left-sided thoracotomy incision was made, and a defect was surgically created in the left diaphragm. The abdominal contents were then gently pulled into the chest using atraumatic instruments. The thoracotomy and uterine incisions were closed in sequence. The uterus was replaced inside the ewe, and the laparotomy was closed. Postoperatively, ewes were allowed to eat and drink ad libitum and were generally standing within 1 h. All animals were treated with scheduled buprenorphine (0.6 mg) for 48 h postoperatively and then as indicated (based on veterinary assessment of pain). The pregnant ewes were then killed at 135 days gestation.

Isolation and culture of fetal ovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells.

The left and right pulmonary arteries were isolated from the fetal sheep with a left diaphragmatic defect as well as aged-matched control animals. Proximal PAEC were isolated as previously described (22). Briefly, conduit pulmonary arteries were separated from fetal sheep, and branching vessels were ligated. Collagenase was used to separate endothelial cells from the vessel wall. PAEC were plated and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Endothelial cell phenotype was confirmed by a typical cobblestone appearance and positive immunostaining for von Willebrand Factor (vWF), endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGF-R2, KDR), positive uptake of acetylated low-density lipoprotein (ac-LDL), and negative staining for desmin. PAEC from passages 3–7 were used for these experiments. Cells from left and right lung and from each animal were kept separate throughout all experiments. The number of animals from which endothelial cells were used for each experiment are listed for each individual assay. For control experiments, cells were harvested from sheep that underwent fetal surgery and were exposed to the similar effects of maternal anesthesia as the CDH sheep.

Initial experiments revealed no significant differences between PAEC obtained from the right and left lungs of the CDH animals. For this reason, all data presented are compiled data from assays performed with cells from both left and right lungs of CDH animals (n = 5 CDH animals, 3 cell lines from the right side and 5 from the left).

Cell growth.

Fetal PAEC from normal (n = 5 animals) and CDH (n = 5 animals) lambs were plated at 3 × 105 cells/well and allowed to adhere. Cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS. Cells were removed from the wells using 0.25% trypsin/0.53 mM ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid digestion and counted daily for 4 days using a hemocytometer. Absolute cell number each day was compared with cell number at day 0 to determine the relative increase over time. PAEC from control and CDH lambs were plated on glass slides with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and allowed to become confluent. Cells were then stained for Ki-67 and activated caspase-3. Control cells were serum starved with serum-free DMEM for 24 h as a positive control for apoptosis and activated caspase-3.

The effects of NO gas (20 ppm) and VEGF (25 ng/ml) on PAEC growth were compared between PAEC from normal (n = 4 animals) and CDH (n = 3 animals) sheep. After plating 3 × 105 cells/well and allowing cells to adhere overnight, media was changed to DMEM and 2.5% FBS, since this was the lowest concentration that supported growth. Cells were placed in either room air conditions or a chamber with NO gas at 20 ppm, or media was supplemented with VEGF protein. Media was changed daily, and cell counts were performed at day 5.

Tube formation assay.

PAEC from normal (n = 4 animals) and CDH (n = 5 animals) lambs were plated on collagen-coated wells to assess the ability of the cells to form capillary-like structures, as previously described (14). Cells (4 × 104 cells/well) were initially plated in serum-free DMEM supplemented with and without VEGF (50 ng/ml). Cells were incubated for 18 h in either room air conditions or with NO gas (20 ppm). Counting of tubular structures was performed under ×10 magnification from four different locations in each well.

NO production.

To assess the amount of intracellular NO produced by the PAEC, we used the 4-amino-5-methylamion-2,7-diflourescein (DAF-FM) compound. This assay was preferred over the Griess Reagent, since the sensitivity of the DAF-FM compound is 3 nM, whereas the detection limit of the Griess Reagent is only 1 μM. PAEC (4 × 104 PAEC/well) were plated on 24-well plates in DMEM and 10% FBS and allowed to adhere and grow for 72–96 h until confluence was reached. PAEC were then washed two times with PBS and treated with DAF-FM compound in phenol red- and serum-free media for 20 min. The DAF-FM compound was washed off the cells, and phenol red- and serum-free media was placed on the cells. Following incubation, fluorescent intensity was measured and compared between control (n = 3 animals) and CDH (n = 3 animals) cells as previously described (7, 13, 28). VEGF protein (25 ng/ml) was used as a positive control to stimulate NO production.

Western blot analysis.

PAEC from normal (n = 3 animals) and CDH (n = 3 animals) lambs were grown on 150-mm cloning plates with DMEM and 10% FBS. When the cells reached 100% confluence, cell lysates were collected, as described previously (4). Protein content of samples was determined using the BCA protein assay (catalog no. 23225; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), using bovine serum albumin as the standard. A 25-μg protein sample was added to each lane and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins from the gel were then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), VEGF-R2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), eNOS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) were detected as previously described (5, 23) using appropriate controls and molecular weight as identified by the manufacturer for the protein of interest. For comparisons of eNOS protein between HP-PAEC and lowly proliferative PAEC (LP-PAEC), different clones of normal PAEC that proliferate at different rates and have different proportions of LP- vs. HP-PAEC were used, since the number of LP-PAEC present at the end of the 14-day single cell assay (described below) are too few to collect protein or mRNA for performing molecular studies. Densitometry was performed using Image Lab (version 4.0.1; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Changes in protein expression were analyzed after normalizing for β-actin expression.

Superoxide measurement.

Both intra- and extracellular superoxide production were measured. A total of 4 × 104 cells/well were plated on 24-well plates in DMEM and 10% FBS and allowed to adhere and grow for 72–96 h until confluence was reached. To measure extracellular superoxide production, 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanalide, disodium salt (XTT) (Sigma) was used. Before treatment, cells were washed two times with PBS and replaced with fresh serum and phenol red-free media. In one-half of the cells, a superoxide inhibitor, SOD, was added (500 U/ml). After 10 min of pretreatment with SOD, the superoxide indicator (XTT) (0.1 mM concentration) was added. The change in absorbance at 470 nm was read by a Bio-Rad 680 microplate reader (Bio-Rad) at 1, 3, 5, and 7 h after addition of the XTT. The difference in absorbance between the untreated cells and those treated with SOD was then calculated. To measure intracellular superoxide, following washing with PBS, cells were treated with dihydroethidium (DHE) (1 μM concentration) in phenol red- and serum-free media for 30 min. The DHE compound was then washed off the cells, and phenol red- and serum-free media was placed on the cells. Cells were then incubated for 60 min with phenol red- and serum-free media. Following incubation, fluorescent intensity was measured and compared between control (n = 3 animals) and CDH (n = 3 animals) cells.

Characterization of HP-PAEC population.

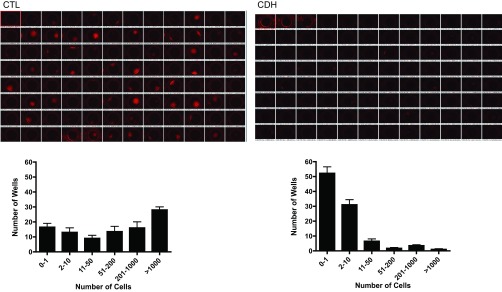

PAEC from control (n = 2 animals) and CDH (n = 2 animals) animals were evaluated using a single cell assay as previously described (17). The Beckman Coulter MoFlo Legacy XPD Cell Sorter was used to place a single PAEC per well in a flat-bottomed 96-well tissue culture plate precoated with type 1 collagen and containing 200 μl of DMEM and 10% FBS. Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Media were changed two times per week for 2 wk. At day 14, each well was stained with propridium iodide for nuclear detection. The culture plate was examined with a fluorescent microscope at ×20 magnification, well-by-well, for endothelial growth. Each well was scored based on the number of cells present and were grouped for analysis according to the number of cells as follows: 0–1, 2–10, 11–50, 51–200, 201–1,000, or >1,000 cells/well. The presence of endothelial cells in both the highly proliferative endothelial cell and lowly proliferative endothelial populations was confirmed by morphology and the presence of common endothelial cell markers on immunohistochemical staining, as described above.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Data from all animals in the control and CDH groups were combined for data analysis. An unpaired t-test was used for growth, tube formation, Western blot analysis, XTT assay, and single cell analysis. Other statistical comparisons were made with ANOVA. Post hoc analysis used Fisher's least-significant difference test (Prism 6 software; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Abnormal lung structure and decreased vessel density in experimental CDH.

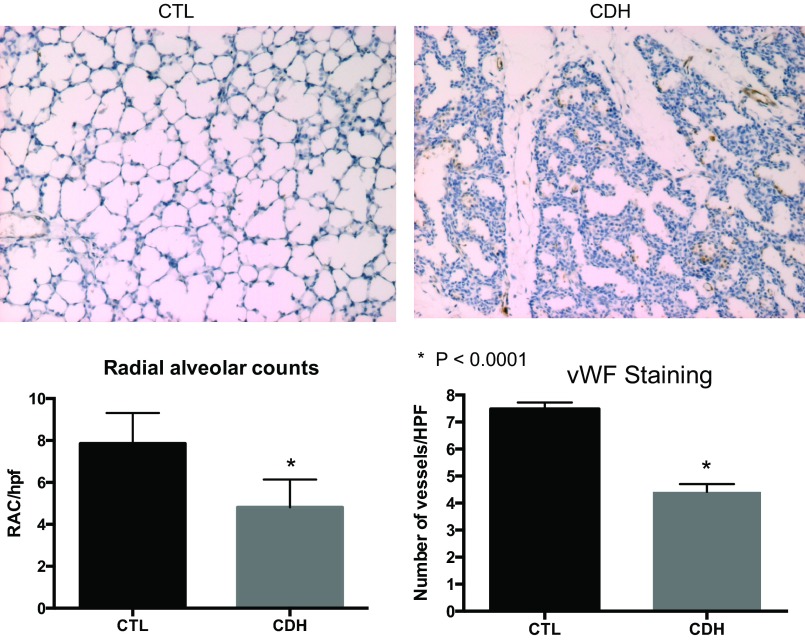

Lung histology from CDH lambs showed decreased alveolarization, increased cellularity, and a thickened interstitium compared with normal lambs. Compared with controls, the number of pulmonary vessels per high-power field at ×10 magnification was decreased by 50% in lungs from CDH lambs (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1). Radial alveolar counts were significantly decreased in CDH sheep with an average of 7.9 in control lungs and 4.8 in lungs from CDH sheep (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 1.

Lung histology from fetal sheep with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) illustrates abnormal distal lung structure with decreased vessel density. Compared with control animals, the distal lung tissue of CDH lambs has a thickened, hypercellular interstitium with reduced alveolarization. Radial alveolar counts were significantly decreased in lungs from CDH sheep (average 7.9 in control animals, 4.8 in CDH animals; P < 0.0001). The number of vessels in the distal lung per high-power field (HPF) was decreased in CDH sheep by 50%. CTL, control; vWF, von Willebrand Factor; RAC, radial avleolar counts.

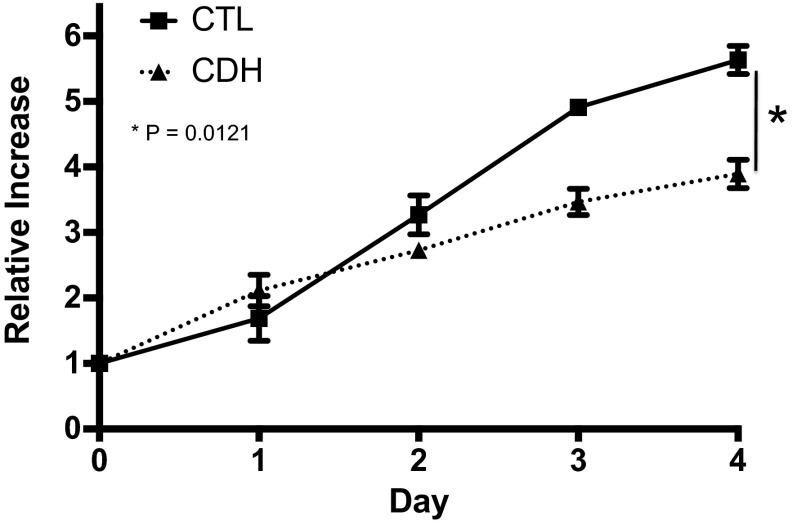

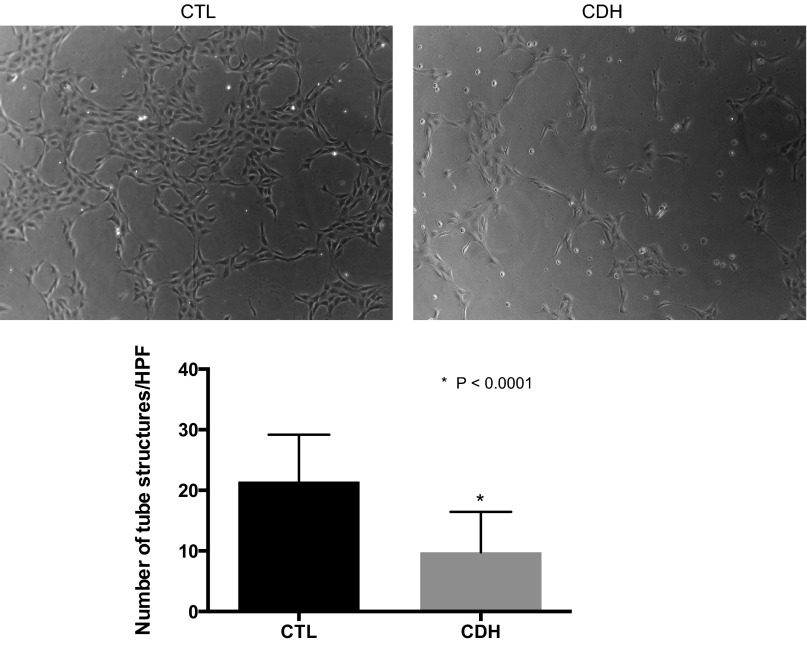

Decreased growth and tube formation in fetal PAEC from CDH sheep.

Compared with controls, the growth of PAEC from CDH lambs was decreased 31% at day 4 (P = 0.01; Fig. 2). PAEC from normal and CDH lambs were uniformly negative for activated caspase-3 protein by immunostaining, indicating that decreased PAEC proliferation and not increased apoptosis accounted for the decrease in cell number in CDH PAEC The ability of PAEC to spontaneously form vascular networks was also decreased in CDH PAEC (Fig. 3). Compared with PAEC from normal animals, the number of tubular structures was decreased by 54% (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Decreased growth in fetal pulmonary artery endothelial cells (PAEC) from sheep with CDH. Compared with PAEC from normal animals, growth of CDH and PAEC numbers were decreased a by 31% at day 4. Bars represent SE from the mean.

Fig. 3.

Decreased tube formation in fetal PAEC from sheep with CDH. Fetal ovine PAECs from control and CDH animals were plated on collagen-lined plates in serum-free media in room air. The ability of CDH cells to form vascular networks was decreased compared with cells from control animals. Error bars represent SE from the mean.

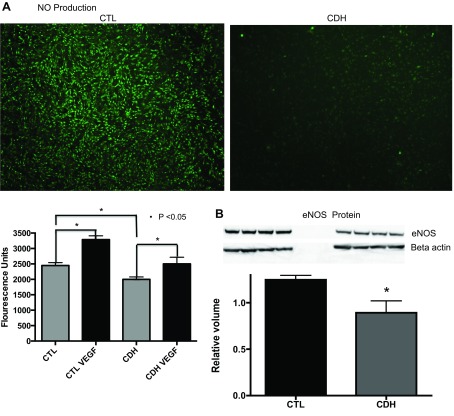

NO and eNOS production are decreased in CDH PAEC.

NO production at baseline by PAEC from CDH sheep was decreased by 18% compared with control PAEC (P < 0.001; Fig. 4A). VEGF treatment stimulated production of NO by 34% above baseline values in control cells (P < 0.0001) and by 25% above baseline in CDH cells (P = 0.05). VEGF treatment restored NO production in CDH cells to levels measured from control cells under baseline conditions. By Western blot analysis, compared with controls, eNOS protein was decreased by 28% (P = 0.0255) in CDH lambs (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Nitric oxide (NO) production in PAEC from sheep with CDH and control animals. The images were taken of control and CDH PAEC after treatment with 4-amino-5-methylamion-2,7-diflourescein (DAF) compound. The DAF compound causes NO to fluoresce. The images demonstrate increased fluorescence from the control PAEC. After quantifying the fluorescence, CDH PAEC produce 18% less NO compared with cells from control animals at baseline. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment stimulated production of NO by 34% above baseline values in control cells (P < 0.0001) and by 25% above baseline in CDH cells (P = 0.05). VEGF treatment restored NO production in CDH cells to levels measured from control cells under baseline conditions (A). As shown, endothelial nitric oxide synthesis (eNOS) protein levels were significantly decreased (B) by Western blot analysis of lysates from CDH PAEC compared with control PAEC.

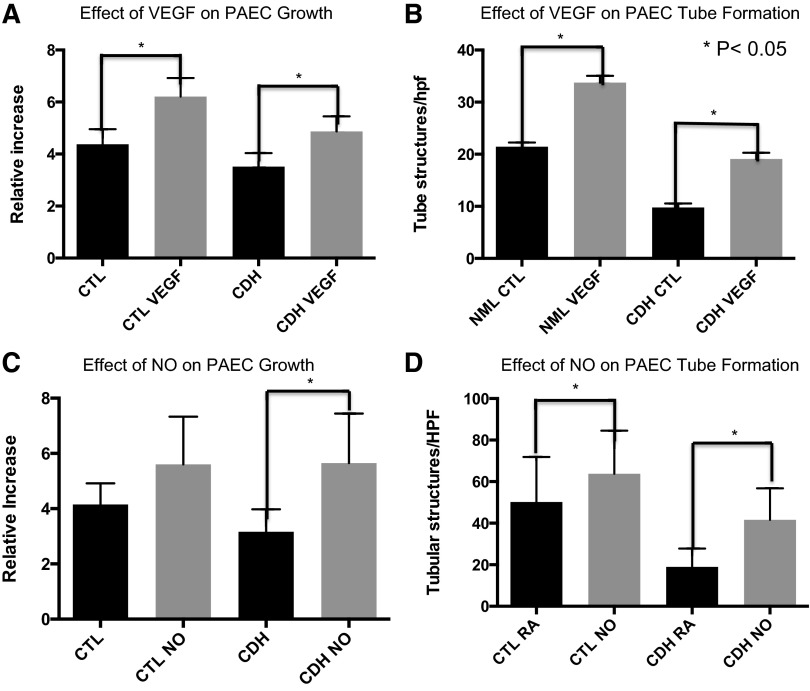

VEGF increases fetal PAEC growth and tube formation.

Compared with untreated CDH PAEC, VEGF treatment increased CDH PAEC number by 38% at day 5 (P = 0.0002; Fig. 5A). VEGF treatment restored CDH PAEC growth to values observed in untreated PAEC from control animals. Additionally, VEGF treatment also led to a 42% increase in the number of control cells at day 5 (P < 0.001). VEGF treatment also increased the number of tubular structures in normal PAEC by 57% (P ≤ 0.0001; Fig. 5B). CDH PAEC showed a similar increase in network formation after VEGF stimulation. The number of tubular structures per high-power field was increased by 65% (P < 0.0001). VEGF stimulation restored tube formation to the level of PAEC from control animals but did not increase it beyond this baseline level.

Fig. 5.

Effect of NO and VEGF on fetal PAEC growth and tube formation. VEGF treatment increases PAEC growth by 39% compared with untreated PAEC from CDH sheep (A). VEGF treatment also increased tube formation in CDH PAEC (B). NO treatment increases fetal PAEC growth by 79% compared with untreated PAEC from CDH sheep (C). NO treatment also increased tube formation in CDH PAEC (D). RA, room air conditions; NO, cells treated in nitric oxide gas at 20 ppm.

NO increases endothelial cell growth and tube formation.

Compared with untreated control PAEC, treatment with exogenous NO gas stimulated growth of PAEC from CDH lambs by 79% (P < 0.0001) at day 5 (Fig. 5C). Growth of PAEC from CDH lambs was similar to growth observed with PAEC from control animals that were also treated with NO gas. There was no difference in PAEC number at day 5 (P = 0.90) between control PAEC and CDH PAEC treated with NO gas. Exogenous NO gas did increase the growth of control PAEC by 35% at day 5; however, this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). Treatment with exogenous NO gas increased tube formation by 27 and 120% (P < 0.0001 for both; Fig. 5D) in control and CDH PAEC, respectively. The number of tube structures was increased compared with baseline. However, exogenous NO gas did not restore tube formation in CDH cells to levels measured in control PAEC stimulated with NO gas. The number of tubular structures formed when CDH cells were exposed to NO gas was 20% less than that of control PAEC exposed to NO gas (P < 0.001).

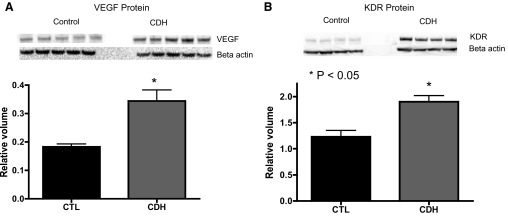

Altered expression of angiogenic markers in fetal PAEC from CDH lambs.

Western blot analysis of PAEC cell lysates from normal and CDH lambs demonstrated increased VEGF and VEGF-R2 (KDR) protein (Fig. 6, A and B). Compared with controls, VEGF protein expression was increased by 89% (P = 0.0029). VEGF-R2 protein expression was increased by 55% (P = 0.0011).

Fig. 6.

VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGF-R2), and eNOS protein content in PAEC lysates from fetal sheep with CDH. By Western blot analysis, VEGF (A) and VEGF-R2 (KDR, B) protein levels were increased in CDH PAECs compared with controls.

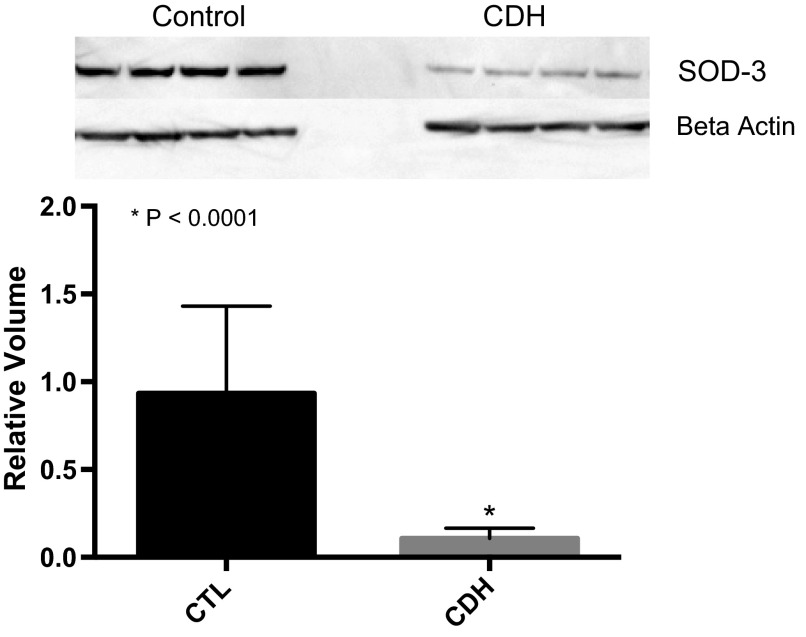

Decreased ecSOD protein expression in fetal PAECS from CDH lambs.

ecSOD protein was significantly decreased in PAECs from CDH lambs compared with control PAEC by Western blot analysis. Compared with controls, ecSOD was decreased by 88% (P < 0.0001; Fig. 7) in CDH PAEC. Production of extracellular superoxide by PAEC from control and CDH lambs did not differ over a 7-h time course. At each time point, 1, 3, 5, and 7 h, after addition of the superoxide detector, the difference in absorbance between untreated cells and cells inhibited with SOD did not differ between PAEC from CDH and control animals. Intracellular superoxide production by DHE fluorescence also did not differ between PAEC from control and CDH animals (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) protein expression is markedly decreased in fetal PAECs from sheep with CDH compared with non-CDH controls.

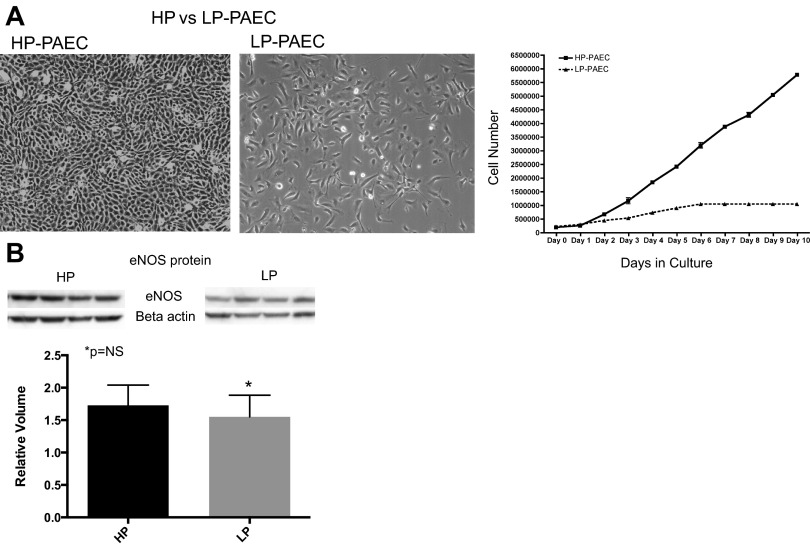

Loss of HP-PAECs in CDH lambs.

Endothelial cells from control animals demonstrate two distinct populations, an HP-PAEC population and a LP-PAEC population. In both populations, endothelial cell phenotype is confirmed by morphology (Fig. 8A) and positive immunostaining for vWF, eNOS, VE-cadherin, VEGF-R2 (KDR), positive uptake of ac-LDL, and negative staining for desmin. HP-PAECs proliferate at an increased rate compared with the LP-PAEC (Fig. 8A). To determine if the differential rates of proliferation were because of changes in eNOS protein expression, eNOS protein was compared between HP-PAECs and LP-PAECs, and no difference in expression was observed between HP-PAECs and LP-PAECs (Fig. 8B). For the single cell clonogenic assays, PAEC from control and CDH animals were plated as single cells in a 96-well plate. At day 14, 29% of control PAEC had formed colonies of >1,000 cells compared with 1% of CDH PAEC (P < 0.0001; Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

A: populations of highly proliferative (HP-PAEC) and lowly proliferative (LP-PAEC) PAEC from normal fetal pulmonary artery vessels. Both populations demonstrate typical endothelial cell appearance (left). HP-PAEC proliferate at a much faster rate than LP-PAEC (right). B: Western blot analysis; eNOS protein levels did not differ between HP and LP PAEC.

Fig. 9.

Loss of a highly proliferative population of fetal PAEC from sheep with CDH. A single PAEC from control and CDH animals was sorted into each well of a 96-well plate and allowed to proliferate. After 2 wk, a significant shift in population and loss of HP-PAECs from CDH lambs was seen. The majority of wells with PAECs from CDH animals had <10 cells, whereas >50% of wells from control animals had >200 cells present.

DISCUSSION

We found that PAEC from an experimental model of CDH in fetal sheep have phenotypic abnormalities that persist in vitro. Compared with PAEC from control animals, PAEC from CDH lambs have decreased numbers of HP-PAEC and impaired growth and tube formation. The decreased PAEC growth is secondary to decreased proliferation and not increased apoptosis. CDH PAEC also demonstrate increased levels of angiogenic proteins VEGF and VEGF-R2 and decreased eNOS protein and NO production, suggesting a defect in the VEGF-NO signaling pathway. Both exogenous NO and VEGF restore PAEC function. Along with these findings, ecSOD is also significantly decreased in CDH PAEC. These findings provide novel insights into possible mechanisms responsible for impaired vascular and alveolar growth seen in neonates with CDH.

Recent work has sought to characterize circulating EPCs and their role in endothelial repair. HP-PAEC reside throughout the vascular endothelium and can be mobilized in a circulating pool of endothelial progenitors, involved in neovasculogenesis via tissue recruitment and homing (3, 17). The single cell clonogenic assay can be used to demonstrate populations of HP-PAEC and progenitor-like properties. Using this assay, Ingram et al. reported that HUVECs and HAECs possess high proliferative potential endothelial colony-forming cells, synonymous with EPCs (18). Current limitations include the inability to define EPCs from a unique set of markers that can unambiguously identify this cell type. Thus, at this stage, we can only characterize differences in vessel wall populations by functional growth traits. Alvarez et al. described a population of resident pulmonary microvascular cells with HP potential within the distal lung (3); however, there are no prior reports of PAEC with HP potential harvested from the proximal pulmonary vasculature. We describe a population of HP-PAEC in the proximal PA and that this population is dramatically decreased in CDH. This is the first report describing this subpopulation of highly proliferative endothelial cells in the proximal pulmonary vasculature and significant decreases in a model of CDH. Although the exact role of HP-PAEC remains unknown, we speculate that this loss of highly proliferative endothelial cells contributes to pulmonary hypoplasia and impaired angiogenesis in CDH.

Despite extensive use of the fetal sheep model of CDH to study innovative surgical interventions (10, 15, 21, 36, 41, 43), little is known about the mechanisms responsible for changes in lung vascular growth and structure. Utilizing this model, others have explored different aspects of lung and airway development and how they contribute to lung hypoplasia in CDH (16, 25, 26, 29, 33), demonstrating that lung development is temporally related to the time of diaphragmatic hernia development. If the hernia develops during formation of conducting airways, the number of bronchial divisions as well as airway size are decreased and, because the saccules and alveoli are the last to develop, the number and size of saccules and alveoli are also decreased (19). Other investigators describe a decrease in lung weight, lung weight-to-body weight ratio, gas exchange surface area, parenchyma to nonparenchyma, and parenchymal airspace to tissue ratios (26) in this model. Although these studies have effectively described the pathology created by the surgically induced diaphragm defect, little is known about the mechanisms responsible for the lung hypoplasia, pulmonary hypertension, and defective pulmonary vascular development in CDH. Recent studies suggest a link between angiogenesis and lung growth (34), demonstrating that disruption of angiogenesis impairs alveolarization (20). These studies led to the idea that preservation of endothelial cell survival and function could enhance vascular development and promote alveolar growth (20). Our finding of decreased CDH PAEC function with impaired growth and tube formation supports these previous reports and suggests that impaired angiogenesis and lung hypoplasia in CDH is the result of PAEC dysfunction. Decreased growth and tube formation in CDH PAEC provides a model for studying the molecular mechanisms responsible for PAEC dysfunction in CDH.

Along with decreased populations of HP-PAECs and decreased growth and tube formation in vitro, we describe increased angiogenic proteins VEGF and VEGF-R2 along with decreased eNOS protein and NO production. Both exogenous VEGF and NO restore PAEC function, and our finding that these cells remain responsive to VEGF stimulation yet produce increased levels of the protein itself suggests a defect in the VEGF signaling pathway requiring pharmacological doses of the protein itself to restore PAEC function. Furthermore decreased eNOS expression, a protein that lies downstream of the upregulated VEGF and VEGF-R2, also suggests a defect in the VEGF signaling pathway.

The decrease in eNOS cannot be attributed to the loss of HP-PAECs, since equivalent amounts of eNOS protein were present in different clones of normal PAEC that proliferate at different rates and have different proportions of HP-PAEC vs. LP-PAEC. For this reason we speculate that mechanisms other than decreased HP-PAEC are responsible for decreased eNOS protein expression in CDH PAEC. Consistent with our studies, previous work using the nitrofen rodent model of CDH have also shown abnormalities in the NO signaling pathway, including a decrease in eNOS protein expression (30) and increases in VEGF protein expression (32). Exogenous NO and VEGF improved lung growth (27, 37), supporting the concept that a defect in VEGF-eNOS signaling contributes to impaired PAEC function in CDH.

Whereas impaired VEGF-eNOS signaling may be responsible for decreased NO production, another potential mechanism that explains the deficit of NO may be an uncoupling of eNOS, preferentially shunting NO precursors toward superoxide production instead of NO (24). There is growing literature demonstrating that an imbalance in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, including superoxide, or impaired scavenging by antioxidants, including ecSOD, contribute to pulmonary fibrosis and vascular remodeling in models of pulmonary hypertension as well as hyperoxia-induced bronchopulmonary dysplasia (2, 31). For this reason, we measured superoxide levels and ecSOD protein expression in normal and CDH PAECs. Superoxide levels were not increased but ecSOD protein expression was significantly decreased in PAEC from CDH lambs. Given that ecSOD acts as a scavenger of extracellular superoxide, we suspect that there is too much localized extracellular superoxide present in the CDH endothelium, leading to oxidative stress and uncoupling of eNOS. This indirect evidence of increased ROS present in CDH endothelium informs the design of future studies that may evaluate the role of antioxidant therapy in this model of CDH. Previous work has demonstrated that overexpression of ecSOD can be protective against lung injury in hyperoxia-exposed mice (44), suggesting a concrete means to further test this hypothesis in a CDH model.

Potential limitations to our findings include the fact that multiple other proangiogenic stimuli and pathways outside of the KDR-VEGF-eNOS pathway exist, which we have not investigated. Additionally, we have documented a decrease in intracellular NO production in CDH PAEC; however, we have not evaluated the amount of NO that is released by these endothelial cells. Our work provides a framework from which to begin further investigation into other possible mechanisms contributing to impaired angiogenesis in CDH. A second concern is the issue of pulmonary macro- vs. microvasculature. We have previously isolated microvascular PAEC from normal fetal sheep; however, using the same techniques, we have been unable to successfully harvest these cells from the distal lung of CDH sheep, which we hypothesize is secondary to markedly reduced number of microvascular PAEC in the distal CDH lung. In the current study we have described endothelial dysfunction in cells originating from the main pulmonary arteries. Given that pulmonary angiogenesis likely arises from the microvasculature, further studies will be needed to also characterize endothelial dysfunction in the distal endothelial microvasculature in CDH.

In conclusion, a surgically induced model of CDH in fetal lambs causes a marked impairment in pulmonary vascular endothelial function with a marked reduction in a HP-PAEC, and decreased cell proliferation and tube formation. Furthermore, our study demonstrates that impaired VEGF-eNOS signaling and decreased ecSOD and increased ROS may contribute to this altered PAEC phenotype. From these data, we speculate that endothelial cell dysfunction contributes to decreased lung vascular growth and pulmonary hypertension in CDH. Treatment strategies that aim to upregulate VEGF or NO signaling or decrease ROS may stimulate angiogenesis in vivo, leading to improved patient outcomes.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health Grants RO1-HL-085703 (S. H. Abman), U01-HL-102235 (S. H. Abman), RO1-HL-68702 (S. H. Abman), and K08-HL-102261 (J. Gien) as well as the Entelilgence Young Investigator Award (J. Gien).

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.N.A., G.J.S., S.H.A., E.N.-G., D.A.P., and J.G. conception and design of research; S.N.A., G.J.S., S.H.A., and J.G. performed experiments; S.N.A., G.J.S., and J.G. analyzed data; S.N.A., G.J.S., S.H.A., E.N.-G., D.A.P., and J.G. interpreted results of experiments; S.N.A. prepared figures; S.N.A. drafted manuscript; S.N.A., G.J.S., S.H.A., E.N.-G., D.A.P., and J.G. edited and revised manuscript; S.N.A., S.H.A., and J.G. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adzick NS, Outwater KM, Harrison MR, Davies P, Glick PL, deLorimier AA, Reid LM. Correction of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in utero. IV. An early gestational fetal lamb model for pulmonary vascular morphometric analysis. J Pediatr Surg 20: 673–680, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed MD, Suliman HB, Folz RJ, Nozik-Grayck E, Goison ML, Mason SN, Auten RL. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects lung development in hyperoxia-exposed newborn mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 400–405, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez DF, Huang L, King JA, ElZarrad MK, Yoder MC, Stevens T. Lung microvascular endothelium is enriched with progenitor cells that exhibit vasculogenic capacity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L419–L430, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balasubramaniam V, Maxey AM, Fouty BW, Abman SH. Nitric oxide augments fetal pulmonary artery endothelial cell angiogenesis in vitro. AM J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L1111–L1116, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balasubramaniam V, Maxey Am Morgan DB, Markham NE, Abman SH. Inhaled NO restores lung structure in eNOS-deficient mice recovering from neonatal hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L119–L127, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balasubramaniam V, Maervis CF, Maxey AM, Markham NE, Abman SH. Hyperoxia reduces bone marrow, circulating, and lung endothelial progenitor cells in the developing lung: implications for the pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L1073–L1084, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortese-Krott MM, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Sansone R, Kuhnle GGC, Thasian-Sivarajah S, Krenz T. Human red blood cells at work: identification and visualization of erythrocytic eNOS activity in health and disease. Blood 120: 4229–4237, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davey MG, Hedrick HL, Bouchard S, Mendoza JM, Schwarz U, Adzick NS, Flake AW. Temporary tracheal occlusion in fetal sheep with lung hypoplasia does not improve postnatal lung function. J Appl Physiol 94: 1054–1062, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Buys Roessingh AS, Dinh-Xuan AT. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: current status and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr 168: 393–406, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.deLorimier AA, Tierney OF, Parker HR. Hypoplastic lungs in fetal lambs with surgically produced congenital diaphragmatic hernia (Abstract). Surgery 62: 12, 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dillon PW, Cilley RE, Mauger D, Zachary C, Meier A. The relationship of pulmonary artery pressure and survival in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 39: 307–312, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujinaga H, Baker CD, Ryan SL, Markham NE, Seedorf GJ, Balasubramaniam V, Abman SH. Hyperoxia disrupts vascular endothelial growth factor-nitric oxide signaling and decreases growth of endothelial colony-forming cells from preterm infants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1160–L1169, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamba J, Gamba LT, Rodrigues GS, Kiyomoto BH, Moraes CG, Tengan CH. Nitric Oxide Synthesis is Increased in Cybrid Cells with m.3243A>G mutation. Int J Mol Sci 14: 394–410, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gien J, Seedorf GJ, Balasubramaniam V, Tseng N, Markham N, Abman SH. Chronic intrauterine pulmonary hypertension increases endothelial cell Rho kinase activity and impairs angiogenesis in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L680–L687, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick PL, Stannard VA, Leach CL, Rossman J, Hosada Y, Morin FC, Cooney DR, Allen JE, Holm B. Pathophysiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernia II: The fetal lamb CDH model is surfactant deficient. J Pediatr Surg 27: 382–387, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellmeyer L, Ballast A, Tekesin I, Sierra F, Ramaswamy A, Lukasewitz P, Niles C, Schmidt S. Evaluation of the development of lung hypoplasia in the premature lamb. Arch Gynecol Obstet 271: 231–234, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Tanaka H, Meade V, Fenoglio A, Mortell K, Pollok K, Ferkowicz MJ, Gilley D, Yoder MC. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood 104: 2752–2760, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Moor DB, Woodard W, Fenoglio A, Yoder MC. Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 105: 2783–2786, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inselmann LS, Mellins RB. Growth and development of the lung. Pediatrics 98: 1–13, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakkula M, Le Cras TD, Gebb S, Hirt KP, Tuder RM, Voelkel NF, Abman SH. Inhibition of angiogenesis decreases alveolarization in the developing rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279: L600–L607, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kavanagh M, Battistini B, Jean S, Crochetiere J, Fournier L, Wessale J, Opgenorth TJ, Cloutier R, Major D. Effect of ABT-627 (A-147627), a potent selective ET-A receptor antagonist, on the cardiopulmonary profile of newborn lams with surgically-induce diaphragmatic hernia. Br J Pharm 134: 1679–1688, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konduri G, Yand Shi JO, Pritchard KA., Jr Decreased association of HSP90 impairs endothelial nitric oxide synthase in fetal lams with persistent pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H204–H211, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Cras TD, Xue C, Rengasamy A, Johns RA. Chronic hypoxia upregulates endothelial and inducible NO synthase gene and protein expression in rat lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 270: L166–L170, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Phsiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1014–R1030, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipsett J, Cool JC, Runciman SI, eFord WD, Kennedy JD, Martin AJ. Effect of antenatal tracheal occlusion on lung development in the sheep model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: A morphometric analysis of pulmonary structure and maturity. Pediatr Pulmonol 25: 257–269, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipsett J, Cool JC, Runciman SI, Ford WD, Kennedy JD, Martin AJ, Parsons DW. Morphometric analysis of preterm fetal pulmonary development in the sheep model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Dev Pathol 1: 17–28, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muehlethaler V, Kunig AM, Seedorf G, Balasubramaniam V, Abman SH. Impaired VEGF and nitric oxide signaling after nitrofen exposure in rat fetal lung explants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L110–L120, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakatsubo N, Kojima H, Kikuchi K, Nagoshi H, Hirata Y, Maeda D, Imai Y, Irimura T, Nagano T. Direct evidence of nitric oxide production from bovine aortic endothelial cells using new fluorescence indicators: diaminofluoresceins. FEBS Lett 427: 263–266, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nobuhara KK, DiFiore JW, Ibla JC, Siddiqui AM, Ferretti ML, Fauza DO, Schnitzer JJ, Wilson JM. Insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression in three models of accelerated lung growth. J Pediatr Surg 33: 1057–1060, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.North AJ, Moya FR, Mysore MR, Thomas VL, Wells LB, Wu LC, Shaul PW. Pulmonary endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene expression is decreased in a rat model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 13: 676–682, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nozik-Grayck E, Suliman HB, Majka S, Albietz J, Van Rheen Z, Roush K, Stenmark KR. Lung EC-SOD overexpression attenuates hypoxic induction of Egr-1 and chronic hypoxic pulmonary vascular remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L422–L430, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oue T, Yoneda A, Shima H, Taira Y, Puri P. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor peptide and gene expression in hypoplastic lung in nitrofen induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia in rats. Pediatr Surg Int 18: 221–226, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papadakis K, Ed Paepe ME, Tackett LD, Piasecki GJ, Luks FI. Temporary tracheal occlusion causes catch-up lung maturation in a fetal model of diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg 33: 1030–1037, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parera MC, van Dooren M, van Kempen M, de Krijger R, Grosveld F, Tibboel D, Rottier R. Distal angiongenesis: a new condept for lung vascular morphogenesis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L141–L149, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reiss I, Schaible T, van den Hout L, Capolupo I, Allegaert K, van Heijst A, Gorett Silva M, Greenough A, Tibboel D, Consortium CDHEURO. Standardized postnatal management of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: the CDH EURO consortium consensus. Neonatology 98: 354–364, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnitzer JJ, Hedrick HL, Pacheco BA, Losty PD, Ryan DP, Doody DP, Donahoe PK. Prenatal glucocorticoid therapy reverses pulmonary immaturity in congenital diaphragmatic hernia in fetal sheep. Ann Surg 224: 430–439, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shinkai M, Shinkai T, Montedonico S, Puri P. Effect of VEGF on the branching morphogenesis of normal and nitrofen-induced hypoplastic fetal rat lung explants. J Pediatr Surg 41: 781–786, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skari H, Bjornland K, Haugen G, Egeland T, Emblem R. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a meta-analysis of mortality factors. J Pediatr Surg 35: 1187–1197, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stege G, Fenton A, Jaffray B. Nihilism in the 1990s: The true mortality of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics 112: 532–535, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suda K, Bigras JL, Bohn D, Hornberger LK, McCrindle BW. Echocardiographic predictors of outcome in newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics 105: 1106–1109, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thebaud B, De Lagausie P, Forgues D, Aigrain Y, Mercier JC, Dinhxuan AT. ETA-receptor blockade and ETB-receptor stimulation in experimental congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 278: L923–L932, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van den Hout L, Sluiter I, Gischler S. Can we improve outcome of congenital diaphragmatic hernia? Pediatr Surg Int 25: 733–743, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Loenhout RB, Tibboel D, Post M, Keijzer R. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: Comparison of animal models and relevance to the human situation. Neonatology 96: 137–149, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wedgwood Lakshminrusimha SS, Fukai T, Russell JA, Schumacker PT, Steinhorn RH. Hydrogen peroxide regulates extracellular superoxide dismutase activity and expression in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 1497–1506, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zengin E, Chalajour F, Gehling UM, Ito WD, Treede H, Lauke H, Weil J, Reichenspurner H, Kilic N, Ergun S. Vascular wall resident progenitor cells: a source for postnatal vasculogenesis. Development 133: 1543–1551, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]