Abstract

Reversing impaired insulin sensitivity has been suggested as treatment for heart failure. However, recent clinical evidence suggests the opposite. Here we present a line of reasoning in support of the hypothesis that insulin resistance protects the heart from the consequences of fuel overload in the dysregulated metabolic state of obesity and diabetes. We discuss pathways of myocardial fuel toxicity, as well as several layers of defense against fuel overload. Our reassessment of the literature suggests that in the heart, insulin-sensitizing agents result in an elimination of some of the defenses, leading to cytotoxic damage. In contrast, a normalization of fuel supply should either prevent or reverse the process. Taken together, we offer a new perspective on insulin resistance of the heart.

Keywords: insulin resistance, metabolism, obesity

this article is part of a collection on Nutrients and Cardiovascular Health and Disease: Glucose, Fatty Acids, and Beyond. Other articles appearing in this collection, as well as a full archive of all collections, can be found online at http://ajpheart.physiology.org/.

Julius Caesar's dictum, “People readily believe what they wish to believe” (De Bello Gallico III, 18) sets the stage for a common assent: because insulin resistance is a prominent feature in heart failure (30, 46), it is commonly thought that “insulin resistance is a primary etiological factor in the development of nonischemic heart failure” (57). Furthermore, impaired insulin sensitivity is regarded an “independent risk factor of mortality in patients with stable chronic heart failure” (17). It has also been proposed that “therapeutically targeting impaired insulin sensitivity may potentially be beneficial in patients with chronic heart failure” (30). However, when this strategy was deployed using insulin-sensitizing agents, it unexpectedly resulted in deleterious effects, including the development of heart failure. First observed in patients receiving the thiazolidinedione rosiglitazone, the authors of a meta-analysis were prompted to issue a warning that “patients and providers should consider the potential for serious adverse cardiovascular effects of treatment with rosiglitazone for type 2 diabetes” (44).

Insulin Resistance, Lipotoxicity, Glucotoxicity, and Reactive Oxygen Species Production

Insulin resistance is defined as a diminished ability of cells to respond to the action of insulin in transporting glucose from the blood stream into the muscle (49). The underlying mechanisms are, however, intricate, because both the insulin signaling pathway and the pathways of intermediary metabolism are complex, intricate, and tightly controlled. The continuous emergence of new hypotheses on the exact mechanisms of insulin resistance underlines the still limited understanding of this metabolic disorder.

Considering insulin resistance in heart, a striking observation is that the normal rat heart, when perfused ex vivo at a physiological workload with glucose as the only substrate, is capable of oxidizing glucose and of maintaining normal cardiac work without the help of insulin (54). In addition, the heart can adapt its glucose metabolism to meet the extra energy demand required by increased workload independent of insulin (7, 16, 21). In a physiological environment, rates of substrate uptake for glucose and fatty acids match rates of substrate utilization. Also, even when plasma levels of energy providing substrates in the dysregulated state of insulin-resistant diabetes are extremely high, there is only a modest rise in the intracellular concentrations of their intermediary metabolites (26). On the other hand, in hearts deficient of insulin receptors protein levels of glucose transporter GLUT4 and uptake of the glucose analog 2-deoxyglucose are both increased (8). So why is it, then, that the heart should be an insulin responsive organ? Why is the failing heart insulin resistant? Why is the heart in diabetes insulin resistant? Impaired insulin-mediated glucose uptake is also a defining feature of the heart in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus although changes in upstream kinase signaling are variable and still incompletely understood (1). Furthermore, it has been shown over and over again that nodal points of the insulin signaling pathway are activated in the heart of insulin-resistant patients and animals (14, 25, 58).

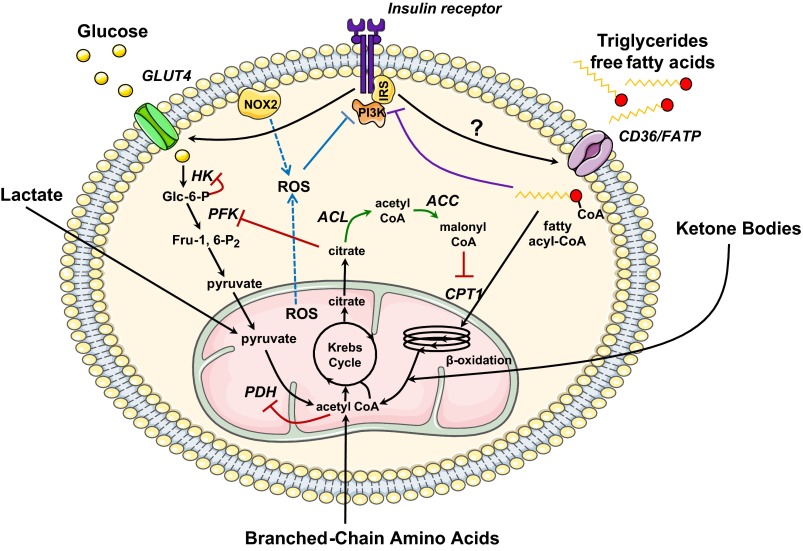

The various mechanisms proposed to explain insulin resistance imply lipotoxicity, glucotoxicity, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). They can be summarized as follows. The inhibition of glucose metabolism by ongoing fatty acid oxidation has some bearing on the crucial role of fatty acids in insulin resistance, as Randle and colleagues (48) originally proposed in 1963 when they wrote, “The high concentration of fatty acids stands in a causal relationship to the abnormalities of carbohydrate metabolism (including, starvation, diabetes and Cushing's syndrome) and suggest that it is a distinct biochemical syndrome, which could appropriately be called the fatty acid syndrome.” Inhibition of glucose metabolism by fatty acids oxidation results from the accumulation of allosteric effectors, which primarily inhibit mitochondrial oxidation of pyruvate and secondarily key glycolytic steps, such as phosphofructokinase and hexokinase (see Fig. 1) (29).

Fig. 1.

Metabolic regulation in the insulin resistant heart. In the normal heart, the control of substrate supply and demand primarily occurs at the level of the plasma membrane and the mitochondria. In 1963, Randle et al. (48) first described a mechanism of competition between fatty acids and glucose for mitochondrial oxidation that would lead to decreased glucose utilization in the presence of increased fatty acid concentrations (48) (red). Fatty acid-mediated inhibition of glucose utilization stems from the allosteric effects of metabolites whose concentration rise in response to increased β-oxidation. At the same time, the activity of phosphofructokinase (PFK), which catalyzes the rate-limiting step in glycolysis, is inhibited by citrate. The resulting increase in glucose 6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) levels in turn inhibits the activity of hexokinase (HK), and rates of glucose uptake are decreased. The mechanism for a reciprocal relation between glucose and fatty acid oxidation was first shown in the heart by McGarry et al. (39). Increased flux of glucose through the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex inhibits β-oxidation through an increase in cytosolic malonyl-CoA, which acts as an inhibitor of the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) reaction (green). We propose that in the stressed heart, an additional level of control exists to limit excess substrate supply through inhibition of the insulin signaling pathway. As suggested by Shulman (52), an alternative mechanism for fatty acid-mediated inhibition of glucose uptake exists, in which the accumulation of fatty acid metabolites such as diacylglycerol, fatty acyl-CoA, and ceramides leads to the activation of novel PKC isoforms and to the inhibitory phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrates (IRSs) (purple). Recent studies by James and colleagues (27) and Beauloye and colleagues (5) suggest that both mitochondrial and cytosolic reactive oxygen species (ROS) decrease insulin sensitivity as a way to limit their own production (blue). Both mechanisms may therefore restore substrate homeostasis by decreasing the translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT4, and possibly of the fatty acid transporter CD36, at the sarcolemma. NOX2, NADPH oxidase 2; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; FATP, fatty acid transport protein; ACL, ATP citrate lyase; ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; Fru-1,6-P2, fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase.

Gerald Shulman and colleague (50, 52) questioned this interpretation on the basis of their observation that glucose uptake was more inhibited than glucose oxidation in muscle of type 2 diabetics. The investigators proposed that muscle insulin resistance results from decreased mitochondrial oxidation of fatty acids, leading to the accumulation of fatty acid-derived molecules (diacylglycerol, ceramide), which activate several stress protein kinases and which, in turn, inhibit insulin signaling, particularly at the level of blunting insulin-stimulated insulin receptor substrate 1-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity (22, 29, 50, 52). This inhibits the insulin-stimulated translocation of the glucose transporter to the plasma membrane (see Fig. 1). Therefore, the ectopic accumulation of fat and lipid derivatives could be the molecular basis of lipotoxicity and mediate insulin resistance. Lipotoxicity also leads to genuine “fatty atrophy” or “metamorphosis,” an old concept first described by Virchow (56) a century and a half ago.

More recent observations have questioned this interpretation of impaired fatty acid oxidation as cause for insulin resistance and lipotoxicity and led to a new hypothesis suggesting that excessive oxidation, unmatched by energy demand, rather than deficient fatty acid oxidation induces insulin resistance. It appears that excessive fatty acid oxidation leads to acylcarnitine and ROS production by mitochondria, thus emphasizing the pivotal role of mitochondria in insulin signaling and action (41). Originally considered a storage depot, the lipid droplet is increasingly recognized as an active participant in many cellular processes (40). Furthermore, new insights into the “metamorphosis of insulin resistance” have come from the application of metabolomics technologies. Based on data reviewed by Newgard (43), branched chain amino acids and related metabolites synergize with lipids to promote insulin resistance in muscle (see Fig. 1). However, the mechanisms behind the decreased ability of insulin to facilitate glucose uptake in insulin responsive tissue is also still not completely clear (15).

ROS, which are produced by both mitochondria and by NADPH oxidases in the cytosol, are major contributors to insulin resistance. Increased ROS production by mitochondria inevitably follows fuel overload unmatched by physical activity, or in biochemical terms, imbalance between increased mitochondrial membrane potential and insufficient ATP demand, leading to increased ROS production at the level of complexes I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (29). Impairment of mitochondrial oxidative capacity, which is a hallmark of established type 2 diabetes, is not an early event in the development of insulin resistance but rather follows increased ROS production in muscles of diet-induced diabetic mice (9). Interestingly, inhibition of mitochondrial ROS production reverses insulin resistance, which is regarded as an antioxidant defense mechanism (27). Lastly, incubation of isolated cardiomyocytes with excess glucose stimulates the nonmitochondrial production of ROS by NADPH oxidase via a mechanism that is not dependent on glucose metabolism and leads to insulin resistance within 24 h (5). This high glucose-induced insulin resistance may be considered a protective mechanism against glucotoxicity (5) (see Fig. 1). In the long term, glucotoxicity also includes glucose-induced insulin resistance due to increased O-linked glycosylation of proteins in the insulin signaling pathway (38) and advanced glycation end-product production, which maintain and worsen ROS formation (60). More recently, we have implicated enhanced glycolytic flux and glucose 6-P accumulation in load-induced mammalian target of rapamycin activation and endoplasmic reticulum stress as causes of contractile dysfunction in the mammalian heart (51). At first glance, these results appear to contradict the findings by Ronglih and coworkers (36) who have shown that cardiac-specific overexpression of the insulin-independent glucose transporter GLUT1 does not compromise cardiac function after induction of pressure overload by ascending aortic constriction (36). However, the enhanced rates of glucose uptake were probably coupled to enhanced rates of glucose oxidation (not measured) preventing the accumulation of glycolytic intermediates (also not measured). In the same model, combined with diet-induced obesity, however, the inability to upregulate fatty acid oxidation resulted in increased oxidative stress, activation of p38 nitrogen-activated protein kinase and contractile dysfunction (59). Although insulin responsiveness was not tested, fuel overload appears to be causally related to cardiac contractile dysfunction in this model.

Irrespective of the mechanisms for insulin resistance in the heart, we offer this hypothesis: if insulin resistance can be regarded as a protection against fuel overload, insulin itself is not deleterious. The culprit is a combination of fuel overload with increased levels of insulin in the circulation.

Central Hypothesis

Our central hypothesis is that insulin modulates myocardial substrate metabolism and that insulin resistance protects the heart muscle from being flooded with excess amounts of fuel (26, 29). This hypothesis is based on at least three lines of evidence: biochemical evidence, physiological observations, and anecdotal reports. Essential to all three is an imbalance between increased substrate uptake and limited or incomplete substrate oxidation in the mitochondria (35, 52), which once established and maintained, results in the development of glucolipotoxicity (60). Glucolipotoxicity is defined as a cellular response to an environment in which both glucose and fatty acid availability is high (60). The term was first used for metabolic derangements causing dysfunction of the pancreatic β-cell (47).

The biochemical evidence for cardioprotection by insulin resistance is probably the strongest of the three lines of evidence. First, there is a striking decrease in interstitial dispersion of insulin in skeletal muscle with diet-induced obesity (34). Second, and perhaps also most important, energy providing substrates inhibit each other before they enter their respective oxidative pathways (54), as recently reviewed by us (29) (see Fig. 1). Fatty acids inhibit glucose oxidation more than they inhibit glycolysis and inhibit glycolysis more than glucose uptake (48). Vice versa, glucose (via malonyl-CoA) inhibits fatty acid oxidation at their entry into the mitochondria (39). We see these control nodes as cytoprotective mechanisms preventing the excessive use of oxidizable substrates that could lead to uncontrolled oxidative stress and irreversible cellular damage. A large number of genetic models overexpressing metabolic regulators in heart muscle with the consequence of “lipotoxicity” support this line of reasoning (4, 10, 12, 19, 20, 24, 45).

The physiological evidence for cardioprotection by insulin resistance is suggested by a downregulation of coronary blood flow during insulin infusion (32) in patients with type 2 diabetes and a decrease in myocardial perfusion reserve in response to increased plasma glucose levels in patients with type 1 diabetes (53). This downregulation occurs in contrast to nitirc oxide-mediated upregulation of forearm blood flow by insulin (6). In a rat model of myocardial infarction induced by coronary artery ligation, the consumption of a high-fat diet has been linked to preserved contractile function despite a marked reduction of insulin signaling in the heart of these animals (13). Ex vivo, metabolic and contractile function of the heart stressed by an acute increase in workload was also improved when myocardial insulin resistance was induced by feeding rats a high-sucrose diet though tighter coupling of glucose uptake (reduced) and oxidation (increased) (25).

Third, there is the obesity paradox. The obesity paradox is a clinical phenomenon that draws attention to the fact that the survival of obese or overweight patients admitted with an acute cardiovascular event is better than in patients who are of normal or below normal weight (3, 28). The term is very appealing to those who point out that both Queen Victoria (1819–1901) and Sir Winston Churchill (1874–1965) were obese and lived well beyond their 80s, although none of the studies confirming the obesity paradox were designed as prospective studies (23). Unger and Scherer (55) have now provided a new perspective on the role of adipose tissue in fuel homeostasis and tissue function. We are inclined to use their metaphor that adipose tissue “loads up with excess fuel, whereas it unloads other organs from the burden of excess fuel.”

Clinical Implications

To restate our central hypotheses, 1) insulin resistance protects the heart from fuel overload and 2) insulin resistance is a marker (rather than a mediator) of premature death and disability from heart disease. We propose that the primary strategy for the treatment of insulin resistance in heart failure patients must involve a reduction in substrate supply rather than an increase in substrate uptake and oxidation by peripheral organs, including the heart. It is of note that metformin, which suppresses hepatic glucose production, lowers mortality in heart failure patients with diabetes when compared with sulfonylurea or insulin-sensitizing treatment (2, 18). In contrast to the prevailing notion that the failing heart is an “engine out of fuel” (42), we consider the failing heart an organ flooded with fuel, whereas the myocyte is unable to convert the excess chemical energy to mechanical energy. Curbing the excess energy stresses the mitochondria (35). Agents lowering substrate supply may indeed be more effective in reversing metabolic and contractile dysfunction of the heart than agents promoting substrate utilization.

Besides metformin, which inhibits hepatic glucose production, other measures or agents of potential benefit for a “fuel flooded” heart include diets low in calories from both fat and carbohydrates, drugs slowing gastric emptying glucagon like peptide 1 and its analogs, or dipeptidylphosphatase 4, inhibitors, inhibitors of the renal sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors, or other inhibitors of gluconeogenesis and hepatic glucose production (glucagon antagonists) (31, 37). We have recently reviewed the effects of bariatric surgery in lowering nutrient overload (33). The list is certainly incomplete and may need to be amended.

Conclusions

Insulin resistance protects the heart for several reasons. Here we have presented evidence in support of the hypothesis that the heart protects itself from the consequences of fuel overload in the dysregulated metabolic state of obesity and diabetes through distinctly different mechanisms offering several layers of defense mechanisms. The defense mechanisms are best described as insulin resistance. We propose that in the heart, insulin-sensitizing agents result in a breakdown of the defenses leading to cytotoxic damage. In contrast, a normalization of fuel supply should either prevent or reverse the process. This is a new perspective to a vexing physiological and clinical problem.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-061483 (to H. Taegtmeyer) and by grants from the American Heart Association (to R. Harmancey) and by the Belgian Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (to C. Beauloye).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.T. and L.H. conception and design of research; H.T. and L.H. drafted manuscript; H.T., C.B., R.H., and L.H. edited and revised manuscript; H.T., C.B., R.H., and L.H. approved final version of manuscript; C.B. and R.H. performed experiments; R.H. prepared figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This hypothesis is based on a lecture presented on July 19, 2010, at WorldPharma 2010 in Copenhagen, Denmark. We thank Roxy A. Tate for expert editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel ED, O'Shea KM, Ramasamy R. Insulin resistance: metabolic mechanisms and consequences in the heart. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 2068–2076, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguilar D, Chan W, Bozkurt B, Ramasubbu K, Deswal A. Metformin use and mortality in ambulatory patients with diabetes and heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 4: 53–58, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anker SD, von Haehling S. The obesity paradox in heart failure: accepting reality and making rational decisions. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90: 188–190, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Augustus AS, Buchanan J, Park TS, Hirata K, Noh HL, Sun J, Homma S, D'Armiento J, Abel ED, Goldberg IJ. Loss of lipoprotein lipase-derived fatty acids leads to increased cardiac glucose metabolism and heart dysfunction. J Biol Chem 281: 8716–8723, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balteau M, Tajeddine N, de Meester C, Ginion A, Des Rosiers C, Brady NR, Sommereyns C, Horman S, Vanoverschelde JL, Gailly P, Hue L, Bertrand L, Beauloye C. NADPH oxidase activation by hyperglycaemia in cardiomyocytes is independent of glucose metabolism but requires SGLT1. Cardiovasc Res 92: 237–246, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron AD, Steinberg HO, Chaker H, Leaming R, Johnson A, Bechtel G. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation contributes to both insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in lean humans. J Clin Invest 96: 786–792, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beauloye C, Marsin AS, Bertrand L, Vanoverschelde JL, Rider MH, Hue L. The stimulation of heart glycolysis by increased workload does not require AMP-activated protein kinase but a wortmannin-sensitive mechanism. FEBS Lett 531: 324–328, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belke DD, Betuing S, Tuttle MJ, Graveleau C, Young ME, Pham M, Zhang D, Cooksey RC, McClain DA, Litwin SE, Taegtmeyer H, Severson D, Kahn CR, Abel ED. Insulin signaling coordinately regulates cardiac size, metabolism, and contractile protein isoform expression. J Clin Invest 109: 629–639, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnard C, Durand A, Peyrol S, Chanseaume E, Chauvin MA, Morio B, Vidal H, Rieusset J. Mitochondrial dysfunction results from oxidative stress in the skeletal muscle of diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. J Clin Invest 118: 789–800, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudina S, Sena S, Theobald H, Sheng X, Wright JJ, Hu XX, Aziz S, Johnson JI, Bugger H, Zaha VG, Abel ED. Mitochondrial energetics in the heart in obesity-related diabetes: direct evidence for increased uncoupled respiration and activation of uncoupling proteins. Diabetes 56: 2457–2466, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown G, Cooper C. Control analysis applied to single enzymes: can an isolated enzyme have a unique rate-limiting step? Biochem J 294: 87–94, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu HC, Kovacs A, Ford DA, Hsu FF, Garcia R, Herrero P, Saffitz JE, Schaffer JE. A novel mouse model of lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest 107: 813–822, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christopher B, Huang HM, Berthiaume J, McElfresh T, Chen X, Croniger C, Muzic RJ, Chandler MP. Myocardial insulin resistance induced by high fat feeding in heart failure is associated with preserved contractile function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1917–H1927, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook SA, Varela-Carver A, Mongillo M, Kleinert C, Khan MT, Leccisotti L, Strickland N, Matsui T, Das S, Rosenzweig A, Punjabi P, Camici PG. Abnormal myocardial insulin signalling in type 2 diabetes and left-ventricular dysfunction. Eur Heart J 31: 100–111, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dela F, Helge JW. Insulin resistance and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 45: 11–15, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depre C, Rider MH, Veitch K, Hue L. Role of fructose 2, 6-bisphosphate in the control of heart glycolysis. J Biol Chem 268: 13274–13279, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, Ponikowski P, Godsland IF, von Haehling S, Okonko DO, Leyva F, Proudler AJ, Coats AJ, Anker SD. Impaired insulin sensitivity as an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with stable chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 1019–1026, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA. Improved clinical outcomes associated with metformin in patients with diabetes and heart failure. Diabetes Care 28: 2345–2351, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finck BN, Bernal-Mizrachi C, Han DH, Coleman T, Sambandam N, LaRiviere LL, Holloszy JO, Semenkovich CF, Kelly DP. A potential link between muscle peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-alpha signaling and obesity-related diabetes. Cell Metab 1: 133–144, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finck BN, Han X, Courtois M, Aimond F, Nerbonne J, Kovacs A, Gross RW, Kelly DP. A critical role for PPARalpha-mediated lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy: modulation by dietary fat content. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1226–1231, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodwin GW, Taylor CS, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J Biol Chem 273: 29530–29539, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffin ME, Marcucci MJ, Cline GW, Bell K, Barucci N, Lee D, Goodyear LJ, Kraegen EW, White MF, Shulman GI. Free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance is associated with activation of protein kinase C theta and alterations in the insulin signaling cascade. Diabetes 48: 1270–1274, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guglin M, Baxi K, Schabath M. Anatomy of the obesity paradox in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev September 15, 2013. [E-publ before print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haemmerle G, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Gorkiewicz G, Meyer C, Rozman J, Heldmaier G, Maier R, Theussl C, Eder S, Kratky D, Wagner EF, Klingenspor M, Hoefler G, Zechner R. Defective lipolysis and altered energy metabolism in mice lacking adipose triglyceride lipase. Science 312: 734–737, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harmancey R, Lam TN, Lubrano GM, Guthrie PH, Vela D, Taegtmeyer H. Insulin resistance improves metabolic and contractile efficiency in stressed rat heart. FASEB J 26: 3118–3126, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harmancey R, Wilson CR, Taegtmeyer H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in obesity. Hypertension 52: 181–187, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoehn KL, Salmon AB, Hohnen-Behrens C, Turner N, Hoy AJ, Maghzal GJ, Stocker R, Van Remmen H, Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ, Richardson AR, James DE. Insulin resistance is a cellular antioxidant defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17787–17792, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, MacLellan WR, Woo MA, Tillisch JH. The relationship between obesity and mortality in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 789–795, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hue L, Taegtmeyer H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E578–E591, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin resistance and risk of congestive heart failure. JAMA 294: 334–341, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inzucchi SE, Masoudi FA, Wang Y, Kosiborod M, Foody JM, Setaro JF, Havranek EP, Krumholz HM. Insulin-sensitizing antihyperglycemic drugs and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the National Heart Care Project. Diabetes Care 28: 1680–1689, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jagasia D, Whiting JM, Concato J, Pfau S, McNulty P. Effect of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus on myocardial insulin responsiveness in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation 103: 1734–1739, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khalaf KI, Taegtmeyer H. Clues from bariatric surgery: reversing insulin resistance to heal the heart. Curr Diab Rep 13: 245–251, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolka CM, Harrison LN, Lottati M, Chiu JD, Kirkman EL, Bergman RN. Diet-induced obesity prevents interstitial dispersion of insulin in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 59: 619–626, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koves TR, Ussher JR, Noland RC, Slentz D, Mosedale M, Ilkayeva O, Bain J, Stevens R, Dyck JR, Newgard CB, Lopaschuk GD, Muoio DM. Mitochondrial overload and incomplete fatty acid oxidation contribute to skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Cell Metab 7: 45–56, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liao R, Jain M, Cui L, D'Agostino J, Aiello F, Luptak I, Ngoy S, Mortensen RM, Tian R. Cardiac-specific overexpression of GLUT1 prevents the development of heart failure attributable to pressure overload in mice. Circulation 106: 2125–2131, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAlister FA, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA. The risk of heart failure in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with oral agent monotherapy. Eur J Heart Fail 10: 703–708, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClain DA, Crook ED. Hexosamines and insulin resistance. Diabetes 45: 1003–1009, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McGarry JD, Mannaerts GP, Foster DW. A possible role for malonyl-CoA in the regulation of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis. J Clin Invest 60: 265–270, 1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muoio DM. Revisiting the connection between intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance: a long and winding road. Diabetologia 55: 2551–2554, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muoio DM, Neufer PD. Lipid-induced mitochondrial stress and insulin action in muscle. Cell Metab 15: 595–605, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neubauer S. The failing heart–an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med 356: 1140–1151, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newgard CB. Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab 15: 606–614, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 356: 2457–2471, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noh HL, Okajima K, Molkentin JD, Homma S, Goldberg IJ. Acute lipoprotein lipase deletion in adult mice leads to dyslipidemia and cardiac dysfunction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E755–E760, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paternostro G, Camici PG, Lammertsma AA, Marinho N, Baliga RR, Kooner JS, Radda GK, Ferrannini E. Cardiac and skeletal muscle insulin resistance in patients with coronary heart disease. A study with positron emission tomography. J Clin Invest 98: 2094–2099, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prentki M, Corkey BE. Are the beta-cell signaling molecules malonyl-CoA and cystolic long-chain acyl-CoA implicated in multiple tissue defects of obesity and NIDDM? Diabetes 45: 273–283, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Randle PJ, Garland PB, Hales CN, Newsholme EA. The glucose fatty-acid cycle. Its role in insulin sensitivity and the metabolic disturbances of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1: 785–789, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 37: 1595–1607, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell 148: 852–871, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sen S, Kundu BK, Wu HC, Hashmi SS, Guthrie P, Locke LW, Roy RJ, Matherne GP, Berr SS, Terwelp M, Scott B, Carranza S, Frazier OH, Glover DK, Dillmann WH, Gambello MJ, Entman ML, Taegtmeyer H. Glucose regulation of load-induced mTOR signaling and ER stress in mammalian heart. J Am Heart Assn 2: e004796, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 106: 171–176, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srinivasan M, Herrero P, McGill JB, Bennik J, Heere B, Lesniak D, Davila-Roman VG, Gropler RJ. The effects of plasma insulin and glucose on myocardial blood flow in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 46: 42–48, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taegtmeyer H, Hems R, Krebs HA. Utilization of energy-providing substrates in the isolated working rat heart. Biochem J 186: 701–711, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unger RH, Scherer PE. Gluttony, sloth and the metabolic syndrome: a roadmap to lipotoxicity. Trends Endocrinol Metab 21: 345–352, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Virchow R. Die Zellularpathologie und ihre Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre. Berlin: Hirschwald, A, 1858, p. 325 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Witteles RM, Fowler MB. Insulin-resistant cardiomyopathy clinical evidence, mechanisms, and treatment options. J Am Coll Cardiol 51: 93–102, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wright JJ, Kim J, Buchanan J, Boudina S, Sena S, Bakirtzi K, Ilkun O, Theobald HA, Cooksey RC, Kandror KV, Abel ED. Mechanisms for increased myocardial fatty acid utilization following short-term high-fat feeding. Cardiovasc Res 82: 351–360, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan J, Young ME, Cui L, Lopaschuk GD, Liao R, Tian R. Increased glucose uptake and oxidation in mouse hearts prevent high fatty acid oxidation but cause cardiac dysfunction in diet-induced obesity. Circulation 119: 2818–2828, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young ME, McNulty P, Taegtmeyer H. Adaptation and maladaptation of the heart in diabetes: Part II: potential mechanisms. Circulation 105: 1861–1870, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]