SUMMARY

Efforts to study development and function of the human cerebral cortex in health and disease have been limited by the availability of model systems. Extrapolating from our understanding of rodent cortical development, we have developed a robust, multistep process for human cortical development from pluripotent stem cells: directed differentiation of human ES and iPS cells to cortical stem/progenitor cells, followed by an extended period of cortical neurogenesis, neuronal terminal differentiation to acquire mature electrophysiological properties, and functional excitatory synaptic network formation. We find that induction of cortical neuroepithelial stem cells from hESCs and hiPSCs is dependent on retinoid signaling. Furthermore, hESC and iPSC differentiation to cerebral cortex recapitulates in vivo development to generate all classes of cortical projection neurons in a fixed temporal order. This system enables functional studies of human cerebral cortex development and the generation of patient-specific cortical networks ex vivo for disease modeling and therapeutic purposes.

INTRODUCTION

The cerebral cortex is the integrative and executive centre of the mammalian central nervous system, making up over three quarters of the human brain 1. Diseases of the cerebral cortex are major causes of morbidity and mortality in children and adults, ranging from developmental conditions such as epilepsy and autism to neurodegenerative conditions of later life, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Much has been learned of the fundamental features of cerebral cortex development, function and disease from rodent models. However, the primate, and particularly the human cerebral cortex, differs in several respects from the rodent 2. In addition to a marked increase in the size of the cerebral cortex relative to the rest of the nervous system, these include the size, complexity, and the nature of its developing stem cell populations 3, an increase in the diversity of upper layer, later born neuronal cell types and the presence of primate-specific neuron types in deep layers 4. Methods to model human cortical development in a controlled, defined manner from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells (collectively referred to as pluripotent stem cells, PSCs) have considerable potential to enable functional studies of human cortical development, circuit formation and function, and for constructing in vitro models of cortical diseases. Given that many of the major diseases of the cerebral cortex are diseases of synaptic function, a goal of the field is to generate cortical networks in vitro that closely resemble those found in vivo.

The cerebral cortex contains two major classes of neurons: approximately 80% are excitatory, glutamatergic projections neurons, generated by cortical stem and progenitor cells, whereas the remaining 20% are GABAergic interneurons that are generated outside the cortex and migrate in during development 5. Glutamatergic projection neurons destined for the six layers of the adult cortex are generated in a stereotyped temporal order, with deep layer neurons produced first and upper layer neurons last 1. In mice, this process takes approximately six days, whereas in humans cortical neurogenesis lasts for over 70 days 6. Once generated, the different classes of cortical projection neurons form local microcircuits between cortical layers 7, as well as longer-range intra- and extra-cortical connections, including corticospinal tract, corticothalamic and callosal projections 8,9.

Mouse ES cells have been shown to be competent to differentiate to cerebral cortex neurons in vitro 10-12. However, a common problem for efforts to model cortical development is that whereas production of deep layer, early-born neurons has been achieved, the complete programme of cortical neurogenesis has not been executed from pluripotent stem cells in culture. This is particularly the case for human corticogenesis from ES cells, which to date has not been achieved in a defined, robust and efficient manner 12,13. It has been proposed that one reason for this failure is that directed differentiation from ES cells may not reproduce the complex stem/progenitor cell populations found in the cortex in vivo 13,14.

While neuroepithelial ventricular zone cells are the primary stem/progenitor population of the cerebral cortex, at least two secondary progenitor populations, basal progenitors/subventricular zone cells and outer subventricular zone (oSVZ) cells have been identified in mouse, ferret and humans 15-17. All three groups of stem/progenitor cells appear to generate projection neurons 15-17, and the increased numbers of oSVZ cells in the primate, and particularly the human, cerebral cortex has been proposed to be a key contributor to the increased size of the human cortex, as well as the diversification of upper layer neuron types 16. Therefore, we hypothesized that to generate all classes of cortical projection neurons, we should aim to differentiate human pluripotent stem cells to cortical stem and progenitor cells that mimic those seen in vivo, and which would undergo the same temporal process of neurogenesis to generate projection neurons of all layers. Based on our current understanding of cerebral cortex development, we identified a set of key milestones for building human cortical networks in vitro: efficient, directed differentiation of human ES and iPS cells (pluripotent stem cells, PSCs) to cortical stem/progenitor cells; genesis of all classes of cortical projection neurons from those stem/progenitor cells, in appropriate numbers and proportions; terminal neuronal differentiation; and synaptogenesis/network formation.

RESULTS

Differentiation of human PSCS to cortical stem cells is retinoid dependent

We explored a number of different approaches to direct differentiation of hES cells to neural stem and progenitor cells of the cerebral cortex in monolayer culture, starting from previously described methods for neural induction using defined media 18,19. Cortical stem/progenitor cells were identified by their expression of the transcription factors Foxg1, Pax6, Otx1/2 and Tbr2. The final demonstration of cortical induction rested on the neuronal output from the neural stem/progenitor cells differentiated from human ES and iPS cells, as discussed below.

We found that combining retinoid signaling with inhibition of SMAD signaling to promote neural induction 19 directed differentiation of hESCs to cerebral cortex stem and progenitor cells with high efficiency (see Suppl. Fig. 1 for a summary of the approach used here). Using this approach, almost all cells (>95%) in the culture are Pax6/Otx1/2/Vimentin-expressing cortical stem and progenitor cells fifteen days after the initiation of neural induction (Fig. 1A–C). Neural stem cell cultures derived by this approach express high levels of Foxg1 and Emx1 mRNA, subsequently express Tbr2 mRNA (Fig. 1B) and do not express any ventrally or caudally expressed transcription factors tested (Dlx1, Nkx2.1, HoxB4 and Isl1). This is in contrast to rosettes ventralised by addition of the hedgehog agonist purmorphamine 20, which express all of those genes and do not express Emx1 (Fig. 1B).

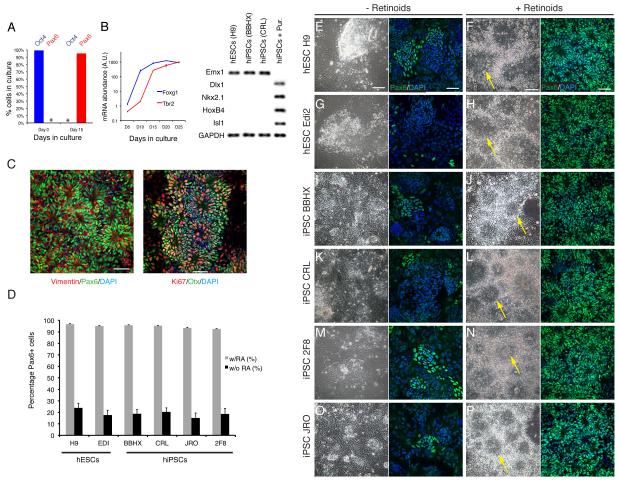

Figure 1. Directed differentiation of human ES and iPS cells to cortical stem and progenitor cells.

A. Over the 15 day neural induction period, Oct4-expressing hES cells differentiate at high efficiency to Pax6-expressing neural stem cells. Asterisks indicate the absence of detectable Pax6-expressing cells at day 0 and of Oct4-expressing cells at day 15. Error bar, s.e.m., n=3 samples for each marker at each timepoint.

B. Quantitative RT-PCR for the cortical stem cell-expressed transcription factor Foxg1 demonstrates that the induction of cortical stem cells begins after 5 days and peaks after 20 days, whereas Tbr2-expressing intermediate progenitor cells and newly-born neurons begin to appear almost a week later. Error bars, s.e.m. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR for the cortical stem cell-expressed Emx1 and the ventral and/or caudally expressed transcription factors Dlx1, Nkx2.1, HoxB4 and Isl1 further shows that neural rosettes generated by this method do not express mRNAs for the ventrally and caudally expressed genes. This is in contrast with rosettes ventralised by treatment with the hedgehog agonist purmorphamine (hiPSCs + Pur.).

C. Confirmation of the cortical identity of hESC-derived stem and progenitor cells (Ki67-positive) by expression of proteins characteristic of cortical stem cells: Pax6, the intermediate filament protein Vimentin and Otx1/2. Scale bars, 50 μm.

D. Quantification of the efficiency of cortical induction, as assayed by the percentage of Pax6-expressing cells (percentage of nuclei, detected with DAPI), in the presence or absence of retinoids in two hESC and four hiPSC cell lines. Values are the average of three cultures for each cell line. Error bars, s.e.m.

E-P Phase contrast and Pax6 immunofluorescence images of hESC and iPSC-derived cultures 12-14 days after the initiation of neural differentiation by dual SMAD inhibition in the absence or presence of exogenous retinoids. Neural rosettes (arrows) were infrequently observed when retinoids were not added to the cultures. Small clusters of Pax6-expressing cells were also observed in these cultures. Efficient induction of neuroepithelial rosettes was observed in all lines, with the majority of cells expressing Pax6. Scale bars, 50 μm.

We tested whether the dependency of cortical differentiation from human embryonic stem cells on retinoids generalized to other pluripotent stem cell lines, both ES and iPS. We differentiated two human ESC lines and four iPSC lines to neural stem cells using the method described here in the presence or absence of retinoids (Fig. 1D–P; Suppl. Fig. 2). The two hESC lines were derived in two different institutions (H9 and Edi2), and the four iPSC lines were derived by two different groups. In the absence of retinoids, cortical neural induction from hES and hiPS cells by dual SMAD inhibition was inefficient, as assessed by Pax6 expression (Fig. 1D–P). Patches of Pax6-expressing cells were observed, accounting for approximately 25% of the cells in each culture (Fig. 1D), but the majority of cells were Pax6-negative. In contrast, inclusion of retinoids (retinol acetate and all-trans retinol) resulted in robust, efficient differentiation of all lines to cortical neural stem/progenitor cells, with almost all cells expressing Pax6 (Fig. 1D) and Otx1/2 (Suppl. Fig. 2). This was the case for all hES and hiPS, independent of origin or derivation method.

Rosettes are polarized similarly to the cortical neuroepithelium

In addition to the expression of transcription factor combinations unique to cortical stem and progenitor cells (see above), the cortical neural rosette cells reported here display features characteristic of the cortical neuroepithelium in vivo. Human ESC-derived neural stem cells form rosette structures following neural induction 21,22. Cortical rosettes also have obvious apico-basal polarity, localizing CD133/prominin, the transferrin receptor, aPKC and ASPM to the apical (luminal) extreme of each cell (Fig. 2A–L; Suppl. Fig. 3). Furthermore, many mitoses are located at the apical/luminal surface of each rosette (Fig. 2A–C), as occurs in vivo. They also localize centrosomes to the extreme apical end of each cell, typically extending into the central lumen of each rosette (Fig. 2M–O; Suppl. Fig. 3), a feature of cortical stem/progenitor cells in vivo. Confirming the parallels with the in vivo cortical neuroepithelium, two proteins that are found at adherens junctions in the cortex, ZO1 and N-cadherin 23, are found tightly localized at the apical, luminal surface of rosette cells (Fig. 2P–R).

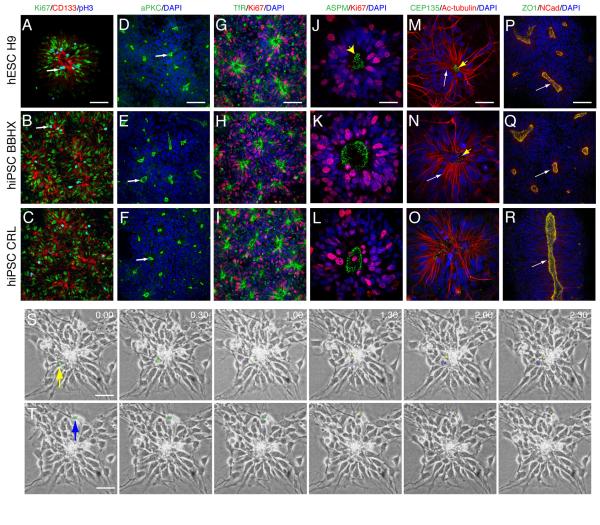

Figure 2. PSC-derived cortical stem/progenitor cells form a polarised neuroepithelium in vitro analogous to the cortical ventricular zone.

A-C. hES (A) and hiPSC (B,C)-derived cortical stem and progenitor cells form polarized neuroepithelial rosettes of proliferating cells (Ki67) in which many mitoses (phosphohistone H3) take place near a central lumen (white arrows) formed from the apical surfaces of the neuroepithelial cells (CD133/Prominin1, red in all panels).

D-L. In addition to CD133/Prominin1, cortical rosettes localize aPKC (D-F), Transferrin receptor (TfR, G-I) and ASPM (J-L) to the apical, luminal pole of the neuroepithelial cells. Scale bars A-C, 100 μm; D, 25 μm.

M-O. Centrosomes (detected by CEP135 immunostaining) are located apically in hESC (M) and hiPSC (N, 0) derived cortical rosettes, as they are in the neuroepithelium in vivo. Acetylated tubulin (white arrows) extends throughout the cortical stem/progenitor cells. Scale bars, 25 μm.

P-R. Proteins localized apically at adherens junctions in cortical stem and progenitor cells in vivo, ZO-1 and N-cadherin 23, are found enriched at the luminal, apical surface of cortical stem/progenitor cells derived from human PSCs. Scale bar, 100 μm.

S. Phase contrast still images, taken at 30-minute intervals of an apically dividing cortical stem/progenitor cell in a hESC-derived cortical rosette. Yellow arrow indicates the nucleus of a neuroepithelial cell (green dot) which translocates apically, dividing into two daughter cells, one of which (yellow) remains at the centre of the rosette, while the other (blue) migrates radially away to the periphery of the rosette. Scale bar, 100 μm.

T. Phase contrast images of a basal (abventricular) mitosis within the rosette shown in (S). In this case, the cell indicated by the arrow/green dot undergoes M-phase at the periphery of the rosette. Scale bar, 100 μm.

A signature feature of neuroepithelia is the process of interkinetic nuclear migration (IKNM), during which the location of the nucleus of each stem/progenitor cell moves during the cell cycle: the nuclei of G1 cells start at the apical surface and migrate towards the basal surface, undergoing S-phase away from the ventricular/apical surface, before undergoing directed nuclear translocation during G2 and mitosis at the apical surface. The localization of M-phase nuclei to the centre of each rosette, at the apical surface, suggested that IKNM takes place in rosettes. To confirm this, we used time-lapse imaging of cell movements in cortical rosettes observe nuclear movements and mitoses. Consistent with the phospho-histone H3 staining, many mitoses took place at the apical/luminal surface (Fig. 2S and Supplementary Movie). All apical mitoses were preceded by a G2-phase in which the nucleus moved from an abventricular position, typically several nuclear diameters away from the lumen of the rosette (Fig.2S). This G2-phase, apically directed movement typically took place over a period of several hours. Mitoses were also observed at the periphery of rosettes (Fig. 2T), consistent with the phospho-histone H3 staining (Fig. 2A–C).

Cortical rosettes reconstitute the complexity of cortical stem cell populations

In the developing cerebral cortex in vivo, the main population of cortical stem cells forms a polarized, pseudostratified neuroepithelium, whereas secondary populations of progenitor cells are found within the inner and outer subventricular zones, referred to as the SVZ and oSVZ, respectively 15,17. Neural stem cells derived by the method reported here contain more than one population of stem and progenitor cells: the majority of cells within the rosettes are Pax6+/Otx+/Ki67+, apico-basally polarized cells with radial processes (Figs. 2A–C and 3A–C). However, as in vivo, there is a second population of Tbr2+/Ki67+ basal progenitor cells at the periphery of each rosette (Fig. 3D–I). Whereas approximately half of Tbr2-expressing cells are Ki67-expressing, cycling progenitor cells (Fig. 3D–F), the other half are newly born, Doublecortin-positive neurons (Fig. 3G–I), as previously described in the developing human cortex in vivo 15. The Tbr2+ population makes up an average of 15% of the cells in each rosette at day 25 (Fig. 3M), of which over 40% are Ki67+ progenitor cells (Fig3N) that would contribute substantially to the neuronal output from the stem/progenitor cell populations. Confirming the presence of both apical and basal progenitor cell populations, mitotic stem/progenitor cells are found both apically, at the rosette lumen, and also in substantial numbers displaced from the rosette lumen (30% on average; Fig. 3O).

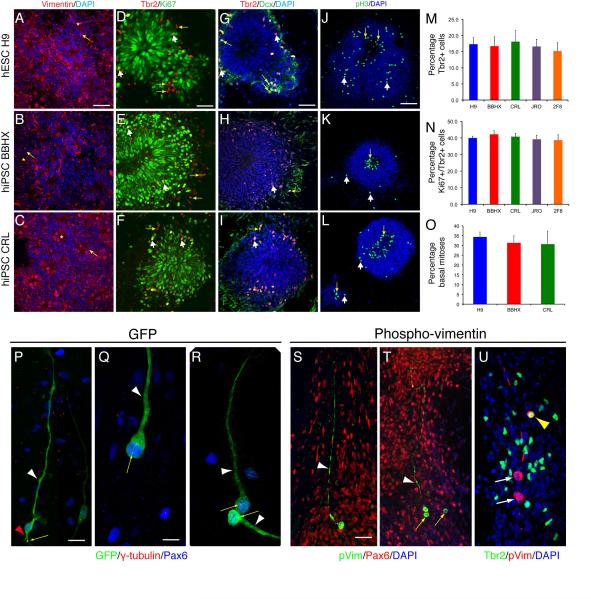

Figure 3. Cortical rosettes differentiated from PSCs generate basal progenitor and outer radial glial cells.

A-C. The majority of cells within hESC (A) and hiPSC (B, C)-derived cortical rosettes are Vimentin-expressing neuroepithelial cells with apical processes (arrows) oriented to the centre of each rosette (asterisks). Scale bar, 50 μm.

D-F. A subpopulation of rosette cells towards the periphery of each rosette express the basal progenitor cell/subventricular zone cell transcription factor Tbr2. A subset of Tbr2+ cells are proliferating cells, as they co-express Ki67 (white arrowheads), whereas others do not (yellow arrows). Scale bar, 50 μm.

G-I. Many of the Tbr2+ cells are newly-born neurons, as they also express Doublecortin (yellow arrows). Scale bar, 50 μm.

J-L. Whereas the majority of mitoses (phospho-histone H3+ cells) are located apically, at the centre of each rosette (yellow arrows), mitoses are also found displaced from the centre or towards the periphery of rosettes (white arrows). These abventricular mitoses indicate the presence of a secondary, basal progenitor cell population within the rosettes. Scale bar, 50 μm.

M, N. Quantification of the proportions of Tbr2+ cells found in cortical rosettes – between 15 and 20% of cells within rosettes derived from different hESC and hiPSC lines express Tbr2 (M). Of the Tbr2+ population, approximately 40% are Ki67+ cycling progenitor cells (N). Error bars, SD.

O. Quantification of the relative proportion of abventricular, basal cortical stem/progenitor cell mitoses (phospho-histone H3+ cells) occurring in cortical rosettes generated from hESCs (H9) and two hiPSC lines. Phospho-histone H3+ mitotic cells were defined as abventricular if found more than 5 cell diameters from the luminal surface. Error bars, SD.

P-R. Representative images of GFP-labelled individual radial glial (ventricular) cells (P) and oRG cells (Q, R). The radial glial cell (P) expresses Pax6 protein (blue nucleus) has an apical process (red arrowhead, P) that contains a centrosome at its apical extreme (yellow arrow) and a long basal process (white arrowhead, P). In contrast, oRG cells (Q, R), which also express Pax6 (blue nuclei), have a single basal process (white arrowheads) and their centrosomes are found in the cell body, near the nucleus (yellow arrows). Scale bars: P, 25 μm; Q, R, 10 μm.

S-U. Two types of mitotic progenitor cells are found in abventricular rosette locations: Pax6-expressing cells with phospho-vimentin+ basal processes (white arrowheads, S, T) that do not express Tbr2 (white arrows, U), which correspond to oRG cells; and Pax6-negative cells lacking basal processes (yellow arrows, T) that express Tbr2 (yellow arrowhead, T) and correspond to basal progenitor cells. Scale bars: S, T, 20 μm; U, 25 μm.

In humans and other mammals, including rodents, there are two separate populations of basal progenitor cells in vivo 15: basal or intermediate progenitor cells, which are Tbr2/Pax6− and lack a basal process, including during mitosis; and outer radial glial cells (oRG) cells, which are Pax6+/Tbr2−, and have an obvious basal process 24. We used two different approaches to investigate the diversity of basal progenitor cells in this system. First, we transiently expressed GFP in rosette cells to delineate their morphology, and combined this with immunostaining for Pax6 and the centrosomal protein gamma-tubulin (Fig. 3P–R). Pax6-expressing cells with both apical and basal processes, with a single centrosome localized to the end of the apical process, defining features of radial glial cells, were commonly found (Fig. 3P). In addition, Pax6-expressing cells with a single, basal process and their centrosomes in the cell body, near the nucleus were also observed, consistent with oRG cells (Fig. 3Q, R). Secondly, we co-stained for Pax6 and phospho-vimentin, or Tbr2 and phospho-vimentin to define the phenotypes of cells with basal processes in M-phase (Fig. 3S–U). We found that cells with obvious, phospho-vimentin+ processes were also Pax6+, whereas round mitotic cells lacking processes were Tbr2+. The combination of these two approaches demonstrates that both basal/intermediate progenitors and oRG cells develop in this system.

Cortical rosettes generate excitatory glutamatergic neurons before producing glia

Cortical neurogenesis, stimulated by the withdrawal of FGF2 from the culture medium, takes place for over two months following neural induction from hES and hiPS cells (Fig. 4A). This is consistent with the approximately 70 day period of cortical neurogenesis in humans 6, compared with the six day cortical neurogenetic period in mice 25. PSC-derived cortical stem and progenitor cells generate glutamatergic projection neurons, including Reelin-expressing neurons (Fig. 4B) and no detectable GABAergic interneurons (Fig. 4C). Although GABAergic interneurons are not generated under cortical induction conditions, at early stages cortical rosettes are plastic with respect to regional identity: treatment with the hedgehog signaling agonist, purmorphamine, ventralises the rosettes, resulting in the genesis of GAD67+ GABAergic interneurons (Suppl. Fig. 5).

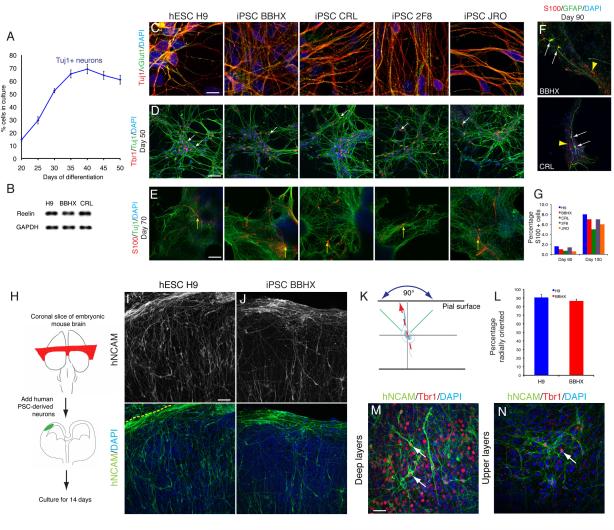

Figure 4. PSC-derived cortical stem cells produce cortical glutamatergic projection neurons before astrocytes.

A. Quantification of neuronal production from PSC-derived cortical stem/progenitor cells. Neurogenesis was stimulated by withdrawal of mitogens, following which increasing numbers of neurons were generated over several weeks. Values are percentage of cells (DAPI+ nuclei) that express the neuron-specific tubulin Tuj1 and are the average of three cultures at each timepoint. Error bars, s.e.m.

B. Reelin mRNA is expressed by PSC-derived cortical neurons at day 50, as detected by RT-PCR.

C. Glutamatergic neuron production from PSC-derived cortical stem/progenitor cells. The overwhelming majority of neurons contain vGlut1-positive punctae in their neurites. Scale bar, 100 μm.

D. Tbr1-expressing, corticothalamic projection neurons differentiate relatively early from PSC-derived cortical stem/progenitor cells. Representative cultures from day 50 for hES and hiPS lines are shown (Tbr1, red; Tuj1, green; DAPI, blue). Scale bar, 50 μm.

E. Astrocytes (S100, red) are generated at a relatively late stage in this system (day 70, as shown here), as also occurs during in vivo development. Scale bar, 50 μm.

F1, F2. GFAP expression follows S100 expression in developing astrocytes: white arrows denote GFAP+/S100+ cells and yellow arrows denote GFAP−/S100+ cells at day 90. Scale bar, 50 μm.

G. Numbers of S100+ glia increase from approximately 1% to 7% of cells in culture between days 60 and 100, consistently across five different hESC and hiPSC lines.

H. Diagram of the mouse brain slice assay system used here. Human PSC-derived cortical neurons were plated as a single cell suspension on coronal slices of embryonic mouse brain and co-cultured for 14 days.

I, J. Confocal images of human cortical neurons (detected by human NCAM expression; I, hESCs; J, iPSCs) in mouse cortical slices after 14 days. The majority of neurons are radially arranged (pial surface is up in each panel), with some neurons tangentially oriented within the marginal zone. Scale bar, 50 μm.

K, L. Quantification of the orientation of human ESC and iPSC-derived cortical neurons in mouse cortical slice culture, excluding neurons in the marginal zone. Neurons were classified as radially oriented if their major neurite was directed towards the pial surface within a 90° segment centered on the vertical (±45° of the perpendicular between the pial and ventricular surface, K). Almost 90% of the neurons from each line were radially oriented (L). n=3 regions counted, total of 500 cells for each cell line; error bars, SD.

M, N. Expression of the layer 6 transcription factor, Tbr1, in human cortical neurons found in deep cortical layers of the mouse cortex (M) and also in upper cortical layers (N). Scale bar, 25 μm.

The initial wave of neurogenesis includes reelin-expressing (Fig. 4B) and deep, Tbr1-expressing layer 6 projection neurons, confirming the cortical identity of the rosettes (Fig. 4D). Rosettes begin to generate astrocytes relatively late in the process, with S100+ astrocytes appearing around day 60 and increasing in numbers over the subsequent 40 days (Fig. 4E-G). Reflecting the heterogeneity of astrocytes and the lack of known robust, pan-astrocyte expressed proteins 26, we observe GFAP+/S100+ and GFAP−/S100+ cells at day 90 (Fig. 4F).

To further assess the differentiation of PSC-derived cortical neurons, we used the cortical slice culture assay 27 to analyse their ability to migrate, terminally differentiate and orient within the mouse cerebral cortex (Fig. 4H). Dissociated PSC-derived neurons were plated on coronal slices of developing mouse brain (embryonic day 14.5) and cultured for 14 days. Human PSC-derived cortical neurons survived in large numbers within the mouse cortex and extended abundant neurites (Fig. 4I, J). Strikingly, the majority (>90%) of human neurons oriented radially within the developing mouse cortex, orthogonal to the ventricular surface (Fig. 4K, L), with a subset aligning tangentially in the marginal zone (Fig. 4I, J). Finally, human PSC-derived neurons maintained their layer identity when cultured in mouse cortex, with many, for example, expressing the layer 6 transcription factor Tbr1 (Fig. 4M, N).

Cortical neurogenesis from PSCs recapitulates in vivo development

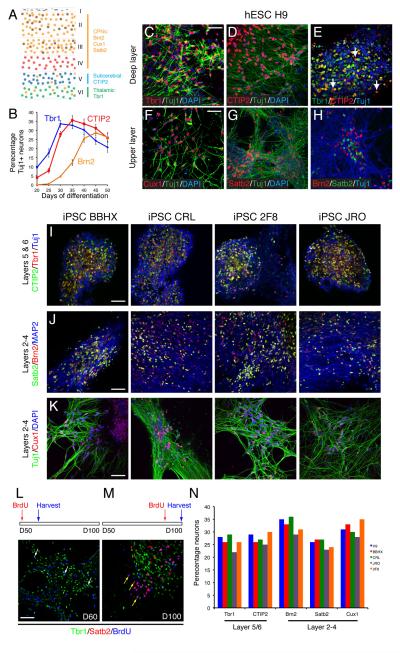

Glutamatergic projection neurons of the adult cortex are generated in a stereotyped temporal order, with deep layer neurons produced first and upper layer neurons last. In rodents, cortical glutamatergic neurons of different laminar fates and projection types can be defined by their expression of different transcription factor combinations (Fig. 5A; for reviews, see 28,29): Tbr1+/CTIP2− (low or absent) layer 6/corticothalamic projection neurons 30; CTIP2+/Tbr1− layer 5/subcortical projection neurons 31; Cux1+/Brn2+ layer 2-4 neurons 32; and Satb2+ layer 2-4 callosal projection neurons 33,34.

Figure 5. Production of human cortical excitatory neurons from PSCs in vitro recapitulates in vivo development.

A. Diagram of classes of cortical projection neurons in the layers of the adult cortex, based on mouse data, with transcription factors expressed in each class of neuron as indicated. CPNs, callosal projection neurons.

B. The order of cortical neurogenesis from human ES cells recapitulates normal development. Deep and upper layer neurons are generated in a temporal order from hESCs, with layer 5 and 6 neurons (Tbr1 and CTIP2) generated before layer 2/3 neurons (Brn2). N=3 experiments scored for each marker. Error bars, s.e.m.

C-E. Differentiation of early born cortical neurons from hESCs. Corticothalamic projection neurons of layer 6 (Tbr1/CTIP2-expressing neurons, A-C) and corticospinal motor neurons of layer 5 (CTIP2-positive, Tbr1-negative neurons, white arrows in C) are both present. Scale bars, 50 μm.

F-H. Upper layer, later born cortical neurons differentiate in this system several weeks after the early born, deep layer neurons. These neurons express Cux1, Satb2 and Brn2. Scale bars, 50 μm.

I-K. Reproducible generation of deep and upper layer projection neurons by four different iPSC lines.

L, M. Birthdating by BrdU administration demonstrates that upper layer, Satb2-expressing neurons are generated from cortical stem/progenitor cells at late stages (as late as day 90) in this system. BrdU addition for 48 hours at day 50, followed by harvesting 7 days later (L), found that the majority of Tbr1-expressing, deep layer neurons have already been generated at this stage, with only a small number of Tbr1+/BrdU+ neurons found (white arrows, L), whereas no Satb2-expressing neurons have differentiated. In contrast, BrdU administration at day 90, followed by cell analysis at day 100, found that large numbers of Satb2-expressing neurons are generated from mitotic stem/progenitor cells at this stage (yellow arrows, N). Scale bar, 50 μm.

N. Relative proportions of different classes of cortical projection neurons generated from humans ES and iPS lines. Approximately equal proportions of deep and upper layer neurons are generated from all lines. See methods for technical details of cell counting.

We used the expression of these factors in neurons to study the timecourse of cortical projection neuron subtype differentiation from PSCs over a 70-day interval, beginning from the withdrawal of FGF2 (Fig. 5B). Deep, layer 6 neurons (Tbr1+) appear first, followed by CTIP2-expressing layer 5 and 6 neurons (Fig. 5B-E). Upper layer, Brn2/Cux1 callosal projection (layer 2–4) neurons differentiate subsequently, beginning between days 25-30, with Satb2 expression appearing late, between days 65 and 80 (Fig. 5B, F-H). The same temporal order of projection neuron production was observed from four different hiPSC lines (Fig. 5I–K).

In contrast to mouse, in which cortical neurogenesis is compressed into a 6-day period, human cortical neurogenesis is thought to span almost 100 days6. To confirm that upper layer genesis from cortical stem/progenitor cells in this system takes place over a similar timeframe, BrdU birthdating was used to analyse the neuronal output from day 50 and day 90 cultures (Fig. 5L, M). In each case BrdU was administered for 48 hours to label cycling stem/progenitor cells and their progeny, and the neuronal output at each stage analysed 7 days later. Birthdating at day 50 found that almost all Tbr1+ neurons had been produced by this stage and no Satb2+/BrdU+ upper layer neurons had yet been produced (Fig. 5L). In contrast, birthdating at day 100 showed that the majority of neurons generated at this stage were Satb2+ upper layer neurons (Fig. 5M). We conclude that cortical neurogenesis in this system follows the same temporal order as occurs in vivo and extends at least as late as day 90.

The combinations of transcriptions factors described above were used to quantify the proportions of different cortical projection neuron types after 70 days in culture. Importantly, roughly equal numbers of deep and superficial layer neurons were present in this system (Fig. 5N), in contrast with previous reports of reduced production of upper-layer neurons from mouse ES cells 11 and the minimal production of upper layer neurons in human ESC-derived aggregate cultures 12. Again, the proportions of different projection neuron subtypes generated from hESCs and four different hiPS lines was notably similar (Fig. 5N).

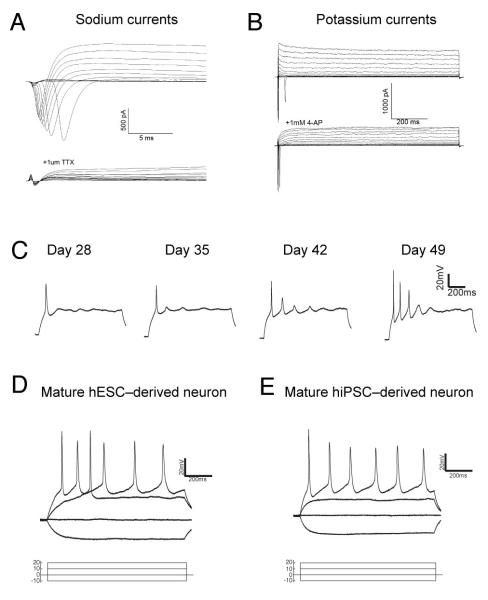

PSC-derived cortical neurons acquire mature electrophysiological properties

We first confirmed that PSC-derived cortical projection neurons differentiate as functional neurons (Fig. 6A, B). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from individual cells (total n=54 neurons) demonstrated the presence of voltage-gated sodium currents, blocked by tetrodotoxin (TTX), and voltage-gated potassium currents, a transient component of which was blocked by 4-aminopyridine (4-AP). Thus, PSC-derived cortical neurons, from both hESCs and hiPSCs, terminally differentiate appropriately to excitable cells (Fig. 6A, B; Suppl. Fig 6).

Figure 6. PSC-derived cortical neurons differentiate to acquire mature electrophysiological properties.

A, B. Voltage-gated sodium and potassium channels in PSC-derived cortical neurons. Current responses to families of step depolarizations from a holding potential of −80 mV to +40 are superimposed. In A, fast-activating and inactivating inward sodium currents are completely blocked by applying TTX. In B, 4-AP blocks a fast-activating transient fraction of outward K current.

C. The electrophysiological properties of PSC-derived cortical neurons mature over time, as exemplified by the change in action potential firing in response to step current injections. Day 28, n=3; day 35, n=4; day 42 n=4; day 49, n=3.

D, E. hESC and hiPSC-derived cortical neurons develop robust regular-spiking behaviour in response to step current injection.

Cortical projection neurons terminally differentiate over days-weeks in the neonatal rodent cortex to develop mature firing properties 35. A similar process takes place in primary cultures of rodent cortical neurons 36. As hESC- and hiPSC-derived cortical neurons age in vitro, their ability to fire bursts of action potentials in response to current injection increased with time (Fig. 6C): young (day 28; n=3) neurons typically fired a single action potential, whereas older (day 49; n=4) neurons fired up to 5 action potentials following current injection. By day 65, many neurons (n=32) robustly fired trains of action potentials when stimulated with steps of current injection. This maturation process was observed in both hES and hiPS-derived cortical neurons (Fig. 6D, E; Suppl. Fig. 5), and is similar to the maturation process that occurs in vivo 35.

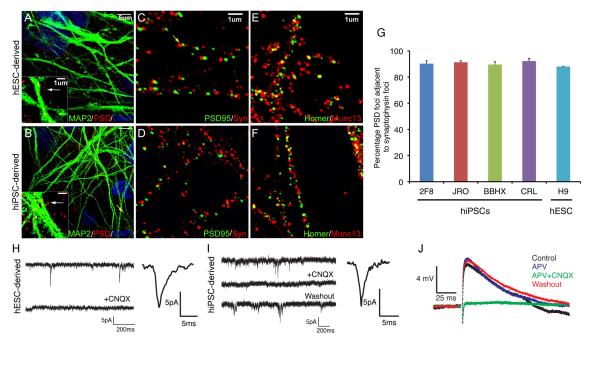

Human PSC-derived cortical neurons form functional excitatory synapses

Synaptogenesis is the critical step in neural network formation. The formation of physical synapses among PSC-derived cortical projection neurons was detected using super-resolution (structured illumination) microscopy to visualize pre- and post-synaptic protein localization. Synapses were defined as regions in the 100s of nanometers in diameter found on or near dendrites (detected by MAP2 staining) where proteins specific to the pre- and post-synaptic compartments were juxtaposed (Fig 7A–F; Suppl. Fig. 7). Two different pairs of pre- and post-synaptic proteins were used to identify synapses: PSD95, enriched at the excitatory, glutamatergic postsynaptic density, together with synaptophysin, a major synaptic vesicle protein; and Homer1, a widely-expressed post-synaptic density protein, with the presynaptic protein Munc13-1. Foci of PSD95 in the 100nm size range were abundant on or near the surface of dendrites of neurons generated from both hESCs and hiPSCs (Fig. 7A, B). Juxtaposed, but non-overlapping, ~100nm foci of pre-synaptic (Synaptophysin, Munc13-1) and post-synaptic (PSD95, Homer1) proteins were also abundant in cultures of both hESC and hiPSC-derived cortical neurons as early as day 28 (Fig. 7C–F; Suppl. Fig. 7). Quantifying the proportions of PSD95 foci that were juxtaposed to foci of post-synaptic synaptophysin in four hiPSC lines and one hESC line revealed that approximately 90% of PSD95 foci are in close approximation to synaptophysin foci (defined as either directly abutting or within one PSD95 diameter, approximately 100nm) in all lines, demonstrating that most PSD95 protein foci represent physical synapses (Fig. 6G).

Figure 7. Formation of functional excitatory synapses among PSC-derived cortical projection neurons.

A-F. Super-resolution microscope images of dendrites (MAP2, green, A, B) showing localization of foci of the excitatory synapse-specific PSD95 protein (A-D). Physical synapses (arrows in all images) were identified by juxtaposition of pre- and post-synaptic protein complexes, either synaptophysin and PSD95 (C, D) or Munc13 and Homer (E, F). Scale bars as shown.

G. Quantification of the proportion of PSD-95 foci that were found juxtaposed to synaptophysin foci in cortical neuronal cultures derived from four hiPSC and one hESC line. In all cases approximately 90% of PSD-95 foci were found colocalised with synaptophysin. Error bars, SD. See methods for technical details.

H, I. Detection of mEPSCs in whole cell recordings of hESC (H) or hiPSC (I)-derived cortical neurons. The AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX blocked the appearance of mEPSCs. Also shown are average mEPSC from hESC (n=20 events; H) and hiPSC (n=20 events; I) derived cortical neurons.

J. Evoked post-synaptic potentials (PSPs) in hESC and hiPSC-derived cortical neurons are excitatory (n=9 neurons) and blocked by the AMPA receptor antagonist CNQX (50 μM; n=4 neurons). Addition of the NMDA receptor antagonist APV (50 μM) had no detectable effect on evoked PSPs (n=2 neurons). Averaged recordings (Control, 7 trials; APV 13 trials; CNQX, 10 trials; Washout, 10 trials) from a representative neuron are shown.

To test whether the observed physical synapses are functional and to characterize their relative maturity, we used whole cell patch-clamp recording to detect miniature excitatory post-synaptic currents (mEPSCs), in cultures between days 45 and 100 (total n=48 neurons). In cultures generated from all hESC and hiPSC lines, mEPSCs 5-10 pA in amplitude were frequently detected (Fig. 7H, I; Suppl. Fig. 8). The mEPSCs were blocked by the AMPA receptor blocker, CNQX (Fig. 7H, I).

In complementary experiments, we analysed and pharmacologically characterized evoked post-synaptic potentials in hESC and hIPSC-derived cortical cultures between days 50 and 80 (Fig. 7J). Using an extracellular stimulating electrode, all evoked PSPs were excitatory (n=9 neurons; peak amplitude X +/− Y mV; Fig. 7J). They had decay time constants typical of non-NMDA receptor mediated EPSPs in cortical neurons (c. 30-50 ms), could be entirely and reversibly blocked by application of 50 μM CNQX (n=4 neurons; Control amplitude A +/− B mV; amplitude in CNQX X +/− Y mV, p < Z; Fig. 7J) and showed no attenuation in the presence of 50 μM APV (n=2 neurons; Control amplitude A +/− B mV; amplitude in APV, X +/− Y, p > Z; Fig 7J). The evoked PSP data demonstrate that human PSC-derived cortical neurons efficiently form functional glutamatergic synapses as early as day 50. Importantly, the synapses analysed at this stage were not nascent, immature synapses, as they contained functional AMPA receptors with no detectable NMDA contribution.

DISCUSSION

We report here a robust and efficient system that recapitulates key stages in human cortical development from pluripotent stem cells. This process consists of a number of distinct steps: the directed differentiation of human PSCs to form a complex population of cortical stem and progenitor cells; an extended period of cortical neurogenesis; a late phase of astrocyte genesis; neuronal terminal differentiation to acquire mature electrophysiological properties; and synaptogenesis and network formation. In contrast to previous reports of directed differentiation of mouse ESCs 11,12, the diversity of cortical projection is reproduced in this system, with approximately equal proportions of both deep (early born) and upper (late born) layer neurons generated over several months in culture.

The critical step in this process is the highly efficient differentiation of human PSCs to cortical neural stem/progenitor cell rosettes, and the genesis of apical and basal progenitor cells in this system. It has been proposed, based on work directing differentiation of mouse ESCs to cortical projection neurons, that certain developmental principles were likely to govern the formation of cortical tissues from PSCs in all species. In particular, retinoids are generally thought to pattern cortical tissue to caudal and/or ventral identities in a concentration dependent manner 14,37, whereas inhibition of hedgehog signaling is thought to be required to block the acquisition of ventral telencephalic identities 11.

We have found that directed differentiation of human PSCs to cerebral cortex stem and progenitor cells does not adhere to those general concepts: inhibition of sonic hedgehog does not promote cortical induction from human PSCs (data not shown), and retinoids are required for efficient cortical induction from human PSCs under the neural induction conditions used here. This finding is consistent with the regulation by retinoids of the transition from neural stem cell expansion to neurogenesis in the mouse cerebral cortex 38 and the retinoid-dependency of the derivation of glutamatergic neurons from mouse ES cells 10. It is questionable whether this mouse-human difference in corticogenesis reflects true in vivo species differences in the pathways for cortical induction and patterning from the embryonic neural tube. It is more likely that they reflect the known differences between mouse and human ESCs, which in turn determine the differing requirements for neural induction from ESCs of each species 39.

Following the establishment of cortical neural rosettes, fundamental principles of neural development appear to govern the competence of those cells to generate complex populations of cortical projection neurons in a cell-intrinsic manner 40. Primary mouse cortical stem/progenitor cells generate projection neurons when grown at clonal density in vitro, although they produce many fewer upper layer/late born neurons than in vivo 41. Withdrawal of mitogenic FGF2, which can be used to expand rosette cells, promotes the onset of neurogenesis in this system. The temporal order of genesis of projection neurons of each layer is preserved in this system: deep, layer 6 neurons are the first to appear, whereas layer 2/3 neurons are the last neurons generated, followed by astrocytes. In contrast to mouse, where cortical neurogenesis takes place over a six-day interval 42, human cortical neurogenesis continues for approximately 100 days in vivo 6. We find that the period of genesis of projection neurons in this system approximates to that seen in the human embryo: deep layer 6 neurons are generated within days of the onset of neurogenesis, whereas upper layer, Satb2-expressing corticofugal neurons do not begin to appear until approximately 60 days later and continue to be generated from cortical stem/progenitor cells as late as day 90.

The ability to generate all classes of cortical projection neurons by directed differentiation of PSCs is likely to be due to the presence of apical and basal progenitor cell types within cortical rosettes. We observe three distinct populations of cortical stem/progenitor cells in human PSC-derived cortical rosettes. Many cells within rosettes are Pax6+/Otx+/Ki67+, apico-basally polarized cells with radial processes, which undergo IKNM and apical mitoses. A second, substantial population of stem/progenitor cells undergoes basal mitoses, and is composed of two subpopulations: a Tbr2+/Ki67+/Pax6− population that lacks basal processes; and a Pax6+/Tbr2− population with lengthy basal processes. These populations approximate to the three known populations of stem/progenitor cells in the developing human cortex: VZ neuroepithelial cells, basal progenitor cells and oRG cells 15. The populations of stem/progenitor cells generated in this system are competent to reliably generate the diversity of projection neuron types found in the human cortex in vivo, suggesting that the complexity of human cortical progenitor types is captured by this system.

A goal of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, as applied to the nervous system, is to create ex vivo models of neural networks that closely resemble those found in vivo. In this system we find that human PSC-derived cortical neurons begin to form physical synapses before the genesis of astrocytes, and that process continues after the appearance of glia. Those synapses are functional, glutamatergic and AMPA receptor-mediated as early as day 50. Nascent glutamatergic synapses go through an early phase when they contain primarily NMDA receptors with little or no AMPA receptor contribution, before recruiting AMPA receptors subsequently 43. We found that spontaneous mEPSCs and evoked PSPs were AMPA-mediated in this system, demonstrating that these synapses had progressed beyond the initial, immature stage. It is noteworthy that we do not observe GABAergic interneuron genesis in this system, reflecting that almost all GABAergic interneurons are generated subcortically and migrate into the cortex 5,44. Engineering cortical circuits from PSCs is likely to require addition of inhibitory interneurons to those developing networks, cells that can be generated by treatment of the cortical rosettes with ventralising morphogens.

The ability to model cortical development from cortical induction through to excitatory synapse and network formation will enable future functional studies of human cortical development and can be exploited to produce specific cortical cell types, such as corticospinal motor neurons. As this approach is equally efficient from human ESCs and iPSCs, patient-specific cortical neurons can be generated for disease modeling, and potentially for therapeutic purposes. One aim of human cortical development and disease modeling is the generation of models that approximate closely with the in vivo cortex, in terms of the specificity of circuits formed and the laminar organization of the different projection neuron types. This will be particularly necessary for diseases of cortical synaptic function, including epilepsy, schizophrenia and cognitive impairment in dementia. Now that it is established that there is no intrinsic obstacle to generating the different classes of projection neurons from PSCs in culture and that those neurons form functional synapses and networks, it will be of interest to explore the potential of this system for engineering human cortical circuits to better model human cortical function and disease pathogenesis.

METHODS

Human pluripotent stem cell culture

Human ES cell research was approved by the Steering Committee for the UK Stem Cell Bank and for the Use of Stem Cell Lines, and carried out in accordance with the UK Code of Practice for the Use of Human Stem Cell Lines. Culture of hES (H9, WiCell Research Institute), and Edi2, (Jenny Nichols, Cambridge Centre for Stem Cell Research) and hiPS cell lines (BBHX, CRL and JRO 45,46; 2F8, Yasuhiro Takashima, Cambridge) was carried out on mitomycin-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) according to standard methods 19. Briefly, cells were maintained in hESC medium (all components Invitrogen unless otherwise stated): DMEM/F12 containing 20% KSR, 6 ng/ml FGF2 (PeproTech), 1mM L-Gln, 100 μm non-essential amino acids, 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 U/ml Penicillin and 50 mg/ml Streptomycin.

Directed differentiation of human ES and iPS cells

hESCs or iPSCs were isolated from MEFs following dissociation to single cells with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies) by a 1 hr pre-plate on gelatin-coated dishes in hESC medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml FGF2 and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor (Calbiochem). The non-adherent pluripotent stem cells were harvested and plated on Matrigel (BD) coated 12-well plates in MEF-conditioned hESC medium with 10 ng/ml FGF2. Once the cell culture reached 95% confluence, neural induction was initiated by changing the culture medium to a culture medium that supports neural induction, neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation (referred to as 3N medium), a 1:1 mixture of N2- and B27-containing media. N2 medium: DMEM/F12, N2 (GIBCO), 5 μg/ml Insulin, 1mM L-Glutamine, 100 μm non-essential amino acids, 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 50 U/ml Penicillin and 50 mg/ml Streptomycin; B27 medium: Neurobasal (Invitrogen), B27 with or without vitamin A (GIBCO), 200 mM Glutamine, 50 U/ml Penicillin and 50 mg/ml Streptomycin. 3N medium was supplemented with either 1 μm Dorsomorphin (Tocris) or 500 ng/ml mouse Noggin-CF chimera (R&D Systems), and 10 μm SB431542 (Tocris) to inhibit TGFβ signaling during neural induction 19. Cells were maintained in this medium for 8-11 days, during which time the efficiency of neural induction was monitored by the appearance of cells with characteristic neuroepithelial cell morphology. Neuroepithelial cells were harvested by dissociation with Dispase and replated in 3N medium including 20 ng/ml FGF2 on poly-ornithine and laminin-coated plastic plates. After a further 2 days, FGF2 was withdrawn to promote differentiation. Cultures were passaged once more with Accutase, replated at 50,000 cells/cm2 on poly-ornithine and laminin-coated plastic plates in 3N medium and maintained for up to 100 days with a medium change every other day.

For quantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from three cultures at each timepoint (days 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25) (Trizol, Sigma). Total RNA was reverse-transcribed and used for quantitative RT-PCR with primers specific to Foxg1 and Tbr2 using the Applied Biosystems 7000 system. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR with primers for Emx1, Dlx1, Nkx2.1, HoxB4 and Isl1 was carried out according to standard techniques on first strand, random-primed cDNA generated from total RNA extracted from cultures grown in the presence or absence of purmorphamine.

Immunocytochemistry, imaging and quantification

Cultures were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS or in ice-cold methanol and processed for immunoflourescent staining and confocal microscopy. Secondary antibodies used for primary antibody detection were species-specific, Alexa-dye conjugates (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies used were: Atypical PKC (ζ) (Santa Cruz sc-216); Acetylated Tubulin (Sigma T7451); BrdU (Abcam ab6326); Brn2 (Santa Cruz sc-6029); Cux1 (CDP) (Santa Cruz sc-13024); Doublecortin (Santa Cruz sc-8066); GAD67 (Chemicon mab5406); Gamma Tubulin (Abcam ab11316); GFAP (Abcam ab4674); GFP (Abcam ab13970); Homer1 (Synaptic Systems 160 011); Ki67 (BD 550609); MAP2 (Abcam ab10588); Munc13 (Synaptic Systems 126 103); N-Cadherin (Abcam ab18203); NCAM, human (Santa Cruz sc-106); Otx1/2 (Milipore AB9566); Pax6 (Covance PRB-278P); Prominin/CD133 (Abcam ab19898); Phospho-histone H3 (Abcam ab10543); PSD95 (Abcam ab2723, ab18258); S100 (Dako Z0311); Satb2 (Abcam ab51502); Sox2 (Santa Cruz sc-17320); Synaptophysin (Abcam ab68851); TBR1 (Abcam ab31940); TBR2/Eomes (Abcam ab23345); Transferrin receptor (Chemicon CBL47); Tuj1 (Covance MMS-435P, PRB-435P); vGlut1 (Synaptic Systems 135303); Vimentin (Abcam ab8978); Vimentin, phospho-Ser55 (MBL D076-3S); ZO1 (Invitrogen 339100).

For quantifying numbers of cells expressing specific cortical neuronal markers, cell cultures were dissociated into single cells with Accutase and resuspended at a density of 100,000 cells/ml. 20,000 cells were plated onto each poly-lysine coated glass slide with a Cytospin Centrifuge (Thermo Scientific), and fixed and stained for confocal microscopy. Statistical comparisons of cell counts were carried out using Student’s t-test.

Cortical rosettes were transfected with a CMV-GFP mammalian expression plasmid with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) to visualize the morphology of individual stem/progenitor cells and for co-staining for Pax6 and gamma-tubulin. BrdU (Sigma) was added to cultures at day 50 or day 90 and removed after 48 hours. Cultures were then fixed seven days later and stained for BrdU, Tbr1 and Satb2 to analyse the cell types generated at each timepoint. Super-resolution microscopy imaging of synaptic proteins was carried out using standard fixation and staining techniques, visualized with a Deltavision OMX system (Applied Precision).

Electrophysiology

Whole cell current clamp recordings were performed at room temperature in artificial cerebral spinal fluid containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 Glucose, 3 Pyruvic Acid, bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2 Borosilicate glass electrodes (resistance 6-10 MΩ) were filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM): 135 K-Gluconate, 7 NaCl, 10 Hepes, 2 Na2ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 2 MgCl2. Cells were viewed using a BW50WI microscope (Olympus) with infrared DIC optics. Recordings were made with a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices). Signals were filtered at 6kHz, sampled at 20kHz with 16-bit resolution, and analysed using Matlab (MathWorks). For assessing functional synaptic connections, we administered brief (0.5-6 ms) voltage (10-99 V) pulses using a constant voltage isolated stimulator (DS2A Mk. II, Digitimer Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, UK) and a platinum/iridium electrode pair (50 μm diameter, CE2E50, FHC, Bowdoin ME, USA) applied to the surface of the culture in the absence of Mg2+. EPSPs were identified as depolarizing potentials appearing in an all-or-nothing way as stimulus voltage was gradually increased. CNQX (50 μM) and APV (50 μM) were bath-applied.

Slice culture of human cortical neurons

Coronal slices of embryonic mouse brain (embryonic day 16) were prepared as 250 μm thick sections using a Leica VT1000S Vibratome. Brain slices were cultured on permeable membrane inserts in Costar Transwell plates, to which N2B27 (3N) medium was added below the membrane. Early stage (day 35 of differentiation) human ESC and iPSC-derived cortical neurons were dissociated to single cells and plated onto the mouse brain slices, essentially as described27. Cultures were maintained for 14 days, before fixing and processing for immunostaining with antibodies to Tbr1 (recognized both mouse and human) and human-specific NCAM antibodies. The orientation of human neurons within the cerebral cortex in mouse brain slices was calculated as described 11, with minor modifications, for cells within the cortical plate, excluding cells within the ventricular region and the marginal zone. Human (hNCAM+) neurons were defined as radially oriented if their apical process was within ±45° of the perpendicular between the pial and ventricular surfaces. Orientation was calculated for 500 cells for both H9 hESC and BBHX hiPSC-derived neurons.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ludovic Vallier (Cambridge) and Yasuhiro Takashima for kindly providing human iPS lines and Jenny Nichols (CSCR, Cambridge) for providing the Edi2 human ES line. We also thank the members of the Livesey lab for their contributions, comments and input to this research. This research benefits from core support to the Gurdon Institute from the Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK and grants to FJL from the Wellcome Trust and the Alzheimer’s Research Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mountcastle VB. The Cerebral Cortex. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Mass.: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finlay BL, Darlington RB. Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science. 1995;268:1578–84. doi: 10.1126/science.7777856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakic P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:724–35. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill RS, Walsh CA. Molecular insights into human brain evolution. Nature. 2005;437:64–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wonders CP, Anderson SA. The origin and specification of cortical interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:687–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caviness VS, Jr., Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS. Numbers, time and neocortical neuronogenesis: a general developmental and evolutionary model. Trends in neurosciences. 1995;18:379–83. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93933-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas RJ, Martin KA. Neuronal circuits of the neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:419–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fame RM, MacDonald JL, Macklis JD. Development, specification, and diversity of callosal projection neurons. Trends in neurosciences. 2011;34:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Bendito G, Molnar Z. Thalamocortical development: how are we going to get there? Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2003;4:276–89. doi: 10.1038/nrn1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibel M, et al. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into a defined neuronal lineage. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1003–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaspard N, et al. An intrinsic mechanism of corticogenesis from embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2008;455:351–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eiraku M, et al. Self-organized formation of polarized cortical tissues from ESCs and its active manipulation by extrinsic signals. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:519–32. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Au E, Fishell G. Cortex shatters the glass ceiling. Cell stem cell. 2008;3:472–4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen DV, Rubenstein JL, Kriegstein AR. Deriving excitatory neurons of the neocortex from pluripotent stem cells. Neuron. 2011;70:645–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen DV, Lui JH, Parker PR, Kriegstein AR. Neurogenic radial glia in the outer subventricular zone of human neocortex. Nature. 2010;464:554–561. doi: 10.1038/nature08845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Tsai JW, Lamonica B, Kriegstein AR. A new subtype of progenitor cell in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Nature neuroscience. 2011;14:555–61. doi: 10.1038/nn.2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fietz SA, et al. OSVZ progenitors of human and ferret neocortex are epithelial-like and expand by integrin signaling. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:690–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ying QL, Stavridis M, Griffiths D, Li M, Smith A. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:183–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambers SM, et al. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–80. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu BY, Zhang SC. Directed differentiation of neural-stem cells and subtype-specific neurons from hESCs. Methods in molecular biology. 2010;636:123–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-691-7_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elkabetz Y, et al. Human ES cell-derived neural rosettes reveal a functionally distinct early neural stem cell stage. Genes Dev. 2008;22:152–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.1616208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, Brustle O, Thomson JA. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1129–33. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotz M, Huttner WB. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2005;6:777–88. doi: 10.1038/nrm1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fietz SA, Huttner WB. Cortical progenitor expansion, self-renewal and neurogenesis-a polarized perspective. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2011;21:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VS., Jr. The leaving or Q fraction of the murine cerebral proliferative epithelium: a general model of neocortical neuronogenesis. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6183–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cahoy JD, et al. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polleux F, Ghosh A. The slice overlay assay: a versatile tool to study the influence of extracellular signals on neuronal development. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:PL9. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.136.pl9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molyneaux BJ, Arlotta P, Menezes JR, Macklis JD. Neuronal subtype specification in the cerebral cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:427–37. doi: 10.1038/nrn2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bedogni F, et al. Tbr1 regulates regional and laminar identity of postmitotic neurons in developing neocortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:13129–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002285107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulfone A, et al. T-brain-1: a homolog of Brachyury whose expression defines molecularly distinct domains within the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 1995;15:63–78. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arlotta P, et al. Neuronal subtype-specific genes that control corticospinal motor neuron development in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:207–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieto M, et al. Expression of Cux-1 and Cux-2 in the subventricular zone and upper layers II-IV of the cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2004;479:168–80. doi: 10.1002/cne.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alcamo EA, et al. Satb2 regulates callosal projection neuron identity in the developing cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2008;57:364–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Britanova O, et al. Satb2 is a postmitotic determinant for upper-layer neuron specification in the neocortex. Neuron. 2008;57:378–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCormick DA, Prince DA. Post-natal development of electrophysiological properties of rat cerebral cortical pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 1987;393:743–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Connors BW, Gutnick MJ, Prince DA. Electrophysiological properties of neocortical neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:1302–20. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maden M, Gale E, Kostetskii I, Zile M. Vitamin A-deficient quail embryos have half a hindbrain and other neural defects. Current biology : CB. 1996;6:417–26. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegenthaler JA, et al. Retinoic acid from the meninges regulates cortical neuron generation. Cell. 2009;139:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallier L, et al. Early cell fate decisions of human embryonic stem cells and mouse epiblast stem cells are controlled by the same signalling pathways. PloS one. 2009;4:e6082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Livesey FJ, Cepko CL. Vertebrate neural cell-fate determination: lessons from the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:109–18. doi: 10.1038/35053522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen Q, et al. The timing of cortical neurogenesis is encoded within lineages of individual progenitor cells. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:743–51. doi: 10.1038/nn1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caviness VS, Jr., et al. Cell output, cell cycle duration and neuronal specification: a model of integrated mechanisms of the neocortical proliferative process. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:592–8. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.6.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groc L, Gustafsson B, Hanse E. AMPA signalling in nascent glutamatergic synapses: there and not there! Trends in neurosciences. 2006;29:132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bystron I, Blakemore C, Rakic P. Development of the human cerebral cortex: Boulder Committee revisited. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:110–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rashid ST, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3127–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI43122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vallier L, et al. Signaling pathways controlling pluripotency and early cell fate decisions of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cells. 2009;27:2655–66. doi: 10.1002/stem.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.