Abstract

Receptor function is dependent on interaction with various intracellular proteins that ensure the localization and signaling of the receptor. While a number of approaches have been optimized for the isolation, purification, and proteomic characterization of receptor–protein interaction networks (interactomes) in cells, the capture of receptor interactomes and their dynamic properties remains a challenge. In particular, the study of interactome components that bind to the receptor with low affinity or can rapidly dissociate from the macromolecular complex is difficult. Here we describe how chemical crosslinking (CC) can aid in the isolation and proteomic analysis of receptor–protein interactions. The addition of CC to standard affinity purification and mass spectrometry protocols boosts the power of protein capture within the proteomic assay and enables the identification of specific binding partners under various cellular and receptor states. The utility of CC in receptor interactome studies is highlighted for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor as well as several other receptor types. A better understanding of receptors and their interactions with proteins spearheads molecular biology, informs an integral part of bench medicine which helps in drug development, drug action, and understanding the pathophysiology of disease.

Keywords: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, chemical crosslinking, mass spectrometry, protein–protein interaction, signaling network, interactome

CROSSLINKING IN THE ANALYSIS OF RECEPTOR INTERACTOMES: TO LINK OR NOT TO LINK?

To biochemically study receptor–protein interactions, one must be able to isolate receptors and their interactomes from the lipid plasma membrane. This process is challenging because of the need to keep diverse protein–protein interactions intact during the extraction and purification of the protein complex. Additionally, the structure and subcellular localization of the receptor in the membrane dictates the chemical conditions required for protein extraction (Thomas and McNamee, 1990). Large polypeptide membrane spanning receptors, such as ligand gated ion channels, demand strong detergent-based solubilization in order to ensure extraction of all receptor subunits. The stringency of these detergent conditions, however, can lead to a loss in numerous receptor–protein associations. Receptors that are embedded in lipid-rich and cholesterol heavy regions of the plasma membrane (such as rafts) require unconventional solubilization methods since these areas are resistant to detergents (Li et al., 2004; Sot et al., 2006). The isolation of membrane bound receptors and their interacting proteins is not trivial and requires extensive optimization on a receptor-by-receptor basis (Kalipatnapu and Chattopadhyay, 2005; Sarramegn et al., 2006).

Cell-based imaging strategies for the study of receptor–protein interactions, such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), circumvent this problem by examining the interaction within an intact cell (Truong and Ikura, 2001). FRET analysis, however, only measures protein–protein interaction at relatively large distances [~100 Angstroms (Å)] and therefore may not be very informative about direct protein coupling (Pollok, 1999). Biochemical assessment of receptor–protein interaction using standard affinity purification methods alone also suffers from several drawbacks. First, the chemical stringency of the biochemical processing steps likely compromises and/or interferes with some receptor–protein interactions. Second, common affinity purification methods such as immunoprecipitation (IP) or pulldown assays heavily rely on the specificity of the antibody or capturing bait and may bias toward abundant proteins and stable protein–protein interactions. In the absence of stringent controls, standard IP experiments can produce substantial false positive results. Finally, current biochemical methods used to detect protein interactions lack cellular spatial specificity; consequently, when a true interaction is discovered the subcellular localization of the interaction is unknown.

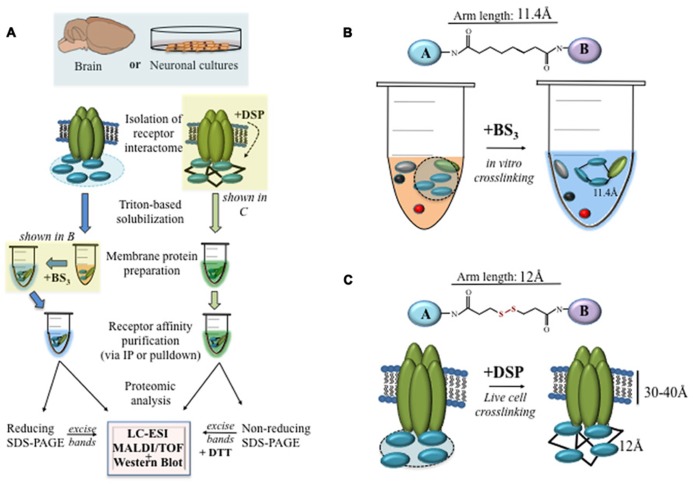

New strategies have emerged for enhancing the detection of protein interactions. Methods such as protein fragment complementation and chemical crosslinking (CC) can stabilize transient or labile protein interactions in vivo and in vitro (Box 1), and therefore enable the identification of many proteins within the interactome (Kluger and Alagic, 2004; Morell et al., 2007). Conventionally CC has been used in the study of extracellular interactions of the receptor such as ligand binding (Gronemeyer and Govindan, 1986; Fanger et al., 1989; Boudreau et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2012), studies now reveal however a utility for cell permeable CC in the identification of the receptor interactome (Figure 1A; Guerrero et al., 2006; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012). In particular, dynamic changes in protein–protein associations within receptor interactomes appear better detected by CC at various stages of the receptor preparation and purification method (Vasilescu et al., 2004). Interactions that are generally too weak or too transient to be discovered in standard pulldown or IP assays alone, can be stabilized by covalent crosslinkers during the membrane solubilization process (Bond et al., 2009; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012). The common use of stringent chemical detergents such as radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffers, which interfere with many types of protein–protein interactions, can also benefit from the addition of covalent crosslinkers which are generally unperturbed by the RIPA reagent. Moreover, CC can be effectively combined with affinity purification protocols such as the IP prior to the mass spectrometry analysis (Vasilescu et al., 2004). To eliminate non-specific interactions of proteins during CC, the assay requires optimization before the start of the study. It is also not uncommon to run non-crosslinked samples in parallel during the course of a study (Kim et al., 2012).

Box 1. Technical Toolbox.

• To crosslink solubilized membrane proteins in vitro with BS3, add 2 mM BS3 to the enriched receptor fraction for 2 h at 4°C and mix (Figure 1B).

• To crosslink proteins in vivo, add 2.5 mM DSP to cultured cells for 2 h at 4°C (Figure 1C). The chemical reaction with DSP can be terminated by the addition of 50 mM Tris-HCI (pH 7.5) at 4°C.

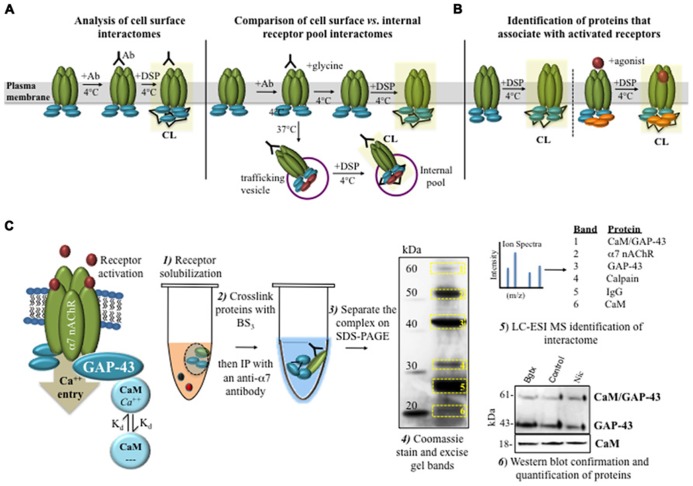

• Clever use of DSP crosslinking enables a range of experiments on receptor–protein interactions including an analysis of receptor interactomes at the cell surface, inside recycled vesicles, or in response to ligand stimulation (Figures 2A,B).

• A crosslinked receptor interactome can be purified using standard methods for immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 1.

Crosslinking the nAChR interactome. (A) A flow chart showing the methods for isolation, crosslinking, and proteomic analysis of nAChR interactomes from brain tissue or neural cells. The experimental design should take into the consideration the choice of the crosslinker as well as the spacer arm. (B) The irreversible crosslinker BS3 is effective for crosslinking nAChR interactomes after membrane protein solubilization with Triton-X. (C) The membrane permeable crosslinker DSP, on the other hand, can be used to crosslink receptors and their interacting proteins in living cells.

A number of crosslinkers have been used to study receptor–protein interactions in cells (Brenner et al., 1985; Shinya et al., 2010; Miteva et al., 2013). These compounds are characterized by differences in their spacer arm as well as the composition of the two amine binding groups that recognize and covalently bind specific functional groups on target proteins (Figures 1B,C; Sinz, 2003; Trakselis et al., 2005). Table 1 lists crosslinkers that have been used to study receptor binding to intracellular proteins. The choice of a spacer arm length, between 5 and 25 Å, is experimentally important because it enables the identification of receptor–protein interactions at specific distances. A recent study utilized agarose beads whose surface was covalently linked with a cleavable chemical crosslinker by spacers of varied lengths to study the interactome of the post-synaptic density isolated from the rodent cortex (Yun-Hong et al., 2011). Experiments successfully demonstrate assemblages of proteins at various subcellular distances and compartments, including the post-synaptic density, thus underscoring the utility of the approach in the characterization of interactomes based on spacer arm properties. However, a possible disadvantage of CC is that some antibodies are no longer able to recognize their target protein after crosslinking (Boudreau et al., 2012).

Table 1.

A summary of crosslinkers used in the analysis of receptor protein interactions.

| Chemical name1 | Membrane permeable | Reversible | Reactive toward | Receptor interactome applications | Spacer arm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSS | Y | N | Amines | Gardoni etal. (2002), Wang etal. (2002),Chu etal. (2004) | 11.4 |

| DSP | Y | Y; by DTT | Amines | Luttrell etal. (1999), Lau and Hall (2001), Quian etal. (2001), Shenoy etal. (2006) | 12.0 |

| BS3 | N | N | Amines | Aldecoa etal. (2000), Nordman and Kabbani (2012) | 11.4 |

| *MBP | Y | N | Sulfydryls | – | <5 |

| *ANB-NOS | Y | N | Amines | – | 7.7 |

| *Sulfo-SAED | N | Y; by DTT | Amines | Yun-Hong etal. (2011) | 23.6 |

*Denotes photo-reactive linkers.

IUPAC Names: DSS, disccinimidyl suberate; DSP, dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate; BS3, bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate; MBP, 4-maleimidobenzophenone; ANB-NOS, N-5-azido-2-nitrobenzoyloxysuccinimide; SAED, sulfosuccinididyl 2-(7-azido-4-methylcoumarin-3 -acetoadmio)-ethyl-1,3 ′-dithiopropionate.

CROSSLINKING ENABLES DETECTION OF PROTEINS THAT BIND THE RECEPTOR IN VARIOUS STATES

Interaction with trafficking and chaperone proteins is important for directing the localization and function of the receptor (Jeanclos et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2006; Kabbani et al., 2007; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012; Colombo et al., 2013). Protein associations may also contribute to receptor conformation at the cell surface (Giniatullin et al., 2005). While the ability to detect receptors at the plasma membrane and in the cytosol has been traditionally reliant on epitope tagging, live cell stain, and cell surface labeling methods such as biotinylation, CC has emerged as a complementary tool in the study of interacting proteins responsible for receptor cellular trafficking and localization. Numerous examples exist in the literature, however, work on β2 adrenergic receptor internalization has been central to understanding mechanisms in GPCR internalization (Lefkowitz and Shenoy, 2005). Key findings on β2 adrenergic receptor internalization have come from experiments using various crosslinkers to detect the association of the receptor with the endocytosis machinery of the cells. First, IP was used in conjunction with DSP [dithiobis(succinimidyl propionate)] crosslinking in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells to quantify changes in β2 adrenergic receptor internalization and demonstrate that the internalized receptor was bound to β-arrestin, which functions as an endocytic adaptor of the receptor complex (Shenoy et al., 2006). In a second similar study, also performed in HEK 293 cells that stably express the β2 adrenergic receptor, DSP was used to show that the β2 adrenergic receptor binds the trafficking and regulatory proteins β-arrestin and c-Src in its “desensitized” state (Luttrell et al., 1999). The study interestingly demonstrates that receptor signaling is sustained even in the absence of ligand binding. A third study on β2 adrenergic receptor internalization employed covalent protein crosslinking with DSP for the detection of transient, agonist-promoted association of dynamin and c-Src, showing how these protein interactions can alter the rate of receptor internalization in the cell (Ahn, 1999).

Crosslinking has also enabled detection of changes in receptor function for the angiotensin receptor (Quian et al., 2001) and has been useful in determining interactions impacted by post-translational modification (Cao et al., 1999; Connolly, 1999; Ehlers, 2000). When combined with cell surface labeling, CC has been effective in determining changes in receptor glycosylation. Differential glycosylation of cell surface human and rat (r) calcitonin (CT) receptor-like receptors (CRLR) as a result of interactions with accessory receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs)-1 or -2 was confirmed by CC using BS3 [bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate] in Drosophila S2 cells (Aldecoa et al., 2000). In this study CC revealed receptor components with the size of rCRLR, increased by the molecular weights of the corresponding RAMP – suggestive of a direct association between the receptor and the accessory protein during ligand activation.

NICOTINIC RECEPTOR INTERACTOMES DEFINED BY CROSSLINKING

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are a family of ligand gated ion channels expressed throughout the nervous system contributing to learning, memory, and goal driven behavior (Changeux, 2012). Recent evidence also reveals that nAChRs operate by coupling to intracellular proteins such as heterotrimeric G proteins (Kabbani et al., 2013). Chronic nicotine exposure gives rise to neural adaptations such as an up-regulation of specific nAChRs through cell-delimited post-translational mechanisms (Sallette et al., 2005; Colombo et al., 2013). These receptor mechanisms are a hallmark of nicotine addiction yet it is still unclear which signaling pathways and mechanism regulate nAChR assembly and trafficking inside the cell. Proteomic studies, based on yeast-two-hybrid as well as conventional IP experiments have led to the identification of several intracellular proteins that bind nAChR subunits in the brain (Kabbani et al., 2007; Paulo et al., 2009; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012; McClure-Begley et al., 2013). Directed protein interaction screens have also enabled discovery of proteins responsible for nAChR trafficking and assembly (Lin et al., 2002; Lansdell et al., 2005; Kabbani, 2008; Rezvani et al., 2009).

In the hippocampus, α7 nAChRs are expressed pre- and post-synaptically, contributing to GABA and glutamate neurotransmission (Liu et al., 2006; Lozada et al., 2012). α7 receptors are also found to mediate the growth of axons (Hancock et al., 2008; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012) and dendrites (Campbell et al., 2011) in the developing hippocampus. Using the membrane impermeable and irreversible crosslinker BS3, we have defined dynamic changes in α7 interaction within solubilized membrane fractions from differentiated PC12 cells and hippocampal neurons (Figure 1B; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012). We show that α7 receptors are directly coupled to a G protein pathway consisting of Gαo, Gprin1, and GAP-43 in growing cells (Nordman and Kabbani, 2012; Figure 1C). In these studies CC was vital to the detection of changes in receptor interaction with signaling molecules and heterotrimeric G proteins. The CC method was also able to enhance the detection of small signaling molecules such as receptor kinases in both Western blots and mass spectrometry experiments (Hu et al., 2010; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012). For example, using BS3 to crosslink the α7 nAChR network after nicotine activation, we identified rapid changes to the calcium-mediated signaling pathway of the receptor, which consisted of a dynamic association between GAP-43 and calmodulin (CaM) in the growing neurite (Figure 2C; Nordman and Kabbani, 2012). In particular, activation of the α7 nAChR was found to promote a rapid association between the receptor and CaM bound GAP-43. This interaction was rapidly reversed by ligand inactivation of the α7 nAChR, showing that receptor association with CaM bound GAP-43 was driven by nAChR channel function and calcium elevation in the cell (Nordman and Kabbani, 2012). These findings on dynamic associations of CaM and GAP-43 within the α7 nAChR interactome could not have been detected using standard IP assays alone underscoring the utility of the crosslinker in the study of protein interactions under physiological conditions. In a similar study, CC with disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) was used in identifying dynamic changes in calcium bound CaM kinase II and subunits of the NMDA glutamate receptor within the post-synaptic density of hippocampal neurons (Gardoni et al., 2002), thus underscoring the utility of the method in the study of rapid calcium driven changes in protein coupling in cells.

FIGURE 2.

Identifying protein interactions that mediate nAChR trafficking, localization, and signaling. (A) Cell surface receptors can be selectively labeled with an anti-α7 nAChR monoclonal Ab. Cell surface labeling (at 4°C) can be combined with DSP in order to crosslink the receptor interactome. Alternatively, antibody labeling and crosslinking can be used to examine changes in the receptor interactome between internalized and cell surface nAChRs. (B) Chemical crosslinking can be used to study the dynamics of nAChR–protein interactions under various ligand treatment conditions. (C) Experimental evidence on α7 nAChR interactions with GAP-43 and CaM in developing neural cells. BS3 was used to crosslink the α7 nAChR interactome from differentiating cells. An IP was utilized to purify the receptor, which was visualized by SDS-PAGE. Protein identity was confirmed using LC-ESI MS and Western blot. These experiments demonstrate dynamic changes in CaM/GAP-43 association with α7 nAChR in response to nicotine activation (Nordman and Kabbani, 2012).

LOOKING AHEAD

Proteomic and yeast-two-hybrid studies on receptor interactions have enabled a broad understanding on the diversity and function of receptor–protein interactions in cells. These studies have enabled an interaction-based framework for defining the mechanisms of receptor signaling. Receptor–protein interaction identification however is not sufficient for understanding how receptors operate in cells. In particular, important questions remain on the spatial specificity and temporal aspects of receptor expression and signaling in cells. For multi-subunit channel receptors such as the glutamate AMPA receptor, the addition of the membrane impermeable linker BS3 has proven effective in the analysis of receptor subunit composition at the cell surface (Boudreau et al., 2012). Similar approaches with the aim of detecting protein–protein interaction in living cells are now necessary. Advancement in the design and experimental utility of CC such as photo-reactive amino acid analogs (Suchanek et al., 2005) promises to enhance the study of receptor–protein interactions in vivo.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Wings for Life Spinal Cord Research Grant to Nadine Kabbani.

REFERENCES

- Ahn S. (1999). Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of dynamin is required for beta 2-adrenergic receptor internalization and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 274 1185–1188 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldecoa A., Gujer R., Fischer J. A., Born W. (2000). Mammalian calcitonin receptor-like receptor/receptor activity modifying protein complexes define calcitonin gene-related peptide and adrenomedullin receptors in Drosophila Schneider 2 cells. FEBS Lett. 471 156–160 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01387-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond C. E., Zimmermann M., Greenfield S. A. (2009). Upregulation of alpha7 nicotinic receptors by acetylcholinesterase c-terminal peptides. PLoS ONE 4:e4846 10.1371/journal.pone.0004846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau A. C., Milovanovic M., Conrad K. L., Nelson C., Ferrario C. R., Wolf M. E. (2012). A protein cross-linking assay for measuring cell surface expression of glutamate receptor subunits in the rodent brain after in vivo treatments. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. Chapter 5, Unit 5.30 1–19 10.1002/0471142301.ns0530s59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. B., Trowbridge I. S., Strominger J. L. (1985). Cross-linking of human T cell receptor proteins: association between the T cell idiotype β subunit and the T3 glycoprotein heavy subunit. Cell 40 183–190 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90321-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell N. R., Fernandes C. C., John D., Lozada A. F., Berg D. K. (2011). Nicotinic control of adult-born neuron fate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 82 820–827 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao T. T., Deacon H. W., Reczek D., Bretscher A, von Zastrow M. (1999). A kinase-regulated PDZ-domain interaction controls endocytic sorting of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature 401 286–290 10.1038/45816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changeux J.-P. (2012). The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: the founding father of the pentameric ligand-gated ion channel superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 287 40207–40215 10.1074/jbc.R112.407668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F., Shan S., Moustakas D. T., Alber F., Egea P. F., Stroud R. M., et al. (2004). Unraveling the interface of signal recognition particle and its receptor by using chemical cross-linking and tandem mass spectrometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 16454–16459 10.1073/pnas.0407456101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo S. F., Mazzo F., Pistillo F., Gotti C. (2013). Biogenesis, trafficking and up-regulation of nicotinic ACh receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 86 1063–1073 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly C. N. (1999). Cell surface stability of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Dependence on protein kinase C activity and subunit composition. J. Biol. Chem. 274 36565–36572 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers M. D. (2000). Reinsertion or degradation of AMPA receptors determined by activity-dependent endocytic sorting. Neuron 28 511–525 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00129-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger B. O., Stephens J. E., Staros J. V. (1989). High-yield trapping of EGF-induced receptor dimers by chemical cross-linking. FASEB J. 3 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardoni F., Caputi A., Cimino M., Pastorino L., Cattabeni F, Di Luca M. (2002). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II is associated with NR2A/B subunits of NMDA receptor in postsynaptic densities. J. Neurochem. 71 1733–1741 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71041733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniatullin R., Nistri A., Yakel J. L. (2005). Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 28 371–378 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronemeyer H., Govindan M. V. (1986). Affinity labelling of steroid hormone receptors. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 46 1–19 10.1016/0303-7207(86)90064-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero C., Tagwerker C., Kaiser P., Huang L. (2006). An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach: quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5 366–378 10.1074/mcp.M500303-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock M. L., Canetta S. E., Role L. W., Talmage D. A. (2008). Presynaptic type III neuregulin1-ErbB signaling targets {alpha}7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors to axons. J. Cell Biol. 181 511–521 10.1083/jcb.200710037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Wang Y., Zhang X., Lloyd J. R., Li J. H., Karpiak J., et al. (2010). Structural basis of G protein-coupled receptor-G protein interactions. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6 541–548 10.1038/nchembio.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanclos E. M., Lin L., Treuil M. W., Rao J., DeCoster M. A., Anand R. (2001). The chaperone protein 14-3-3eta interacts with the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit. Evidence for a dynamic role in subunit stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 276 28281–28290 10.1074/jbc.M011549200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N. (2008). Proteomics of membrane receptors and signaling. Proteomics 8 4146–4155 10.1002/pmic.200800139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N., Nordman J. C., Corgiat B. A., Veltri D. P., Shehu A., Seymour V. A., et al. (2013). Are nicotinic acetylcholine receptors coupled to G proteins? Bioessays 35 1025–1034 10.1002/bies.201300082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani N., Woll M. P., Levenson R., Lindstrom J. M., Changeux J.-P. (2007). Intracellular complexes of the beta2 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in brain identified by proteomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 20570–20575 10.1073/pnas.0710314104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalipatnapu S., Chattopadhyay A. (2005). Membrane protein solubilization: recent advances and challenges in solubilization of serotonin1A receptors. IUBMB Life 57 505–512 10.1080/15216540500167237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. M., Yi E. C., Kim Y. (2012). Mapping protein receptor-ligand interactions via in vivo chemical crosslinking, affinity purification, and differential mass spectrometry. Methods 56 161–165 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger R., Alagic A. (2004). Chemical cross-linking and protein-protein interactions-a review with illustrative protocols. Bioorg. Chem. 32 451–472 10.1016/j.bioorg.2004.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdell S. J., Gee V. J., Harkness P. C., Doward A. I., Baker E. R., Gibb A. J., et al. (2005). RIC-3 enhances functional expression of multiple nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes in mammalian cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 68 1431–1438 10.1124/mol.105.017459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau A. G., Hall R. A. (2001). Oligomerization of NHERF-1 and NHERF-2 PDZ domains: differential regulation by association with receptor carboxyl-termini and by phosphorylation. Biochemistry 40 8572–8580 10.1021/bi0103516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz R. J., Shenoy S. K. (2005). Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science 308 512–517 10.1126/science.1109237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Shaw A. R. E., Zhang N., Mak A., Li L. (2004). Lipid raft proteomics: analysis of in-solution digest of sodium dodecyl sulfate-solubilized lipid raft proteins by liquid chromatography-matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics 4 3156–3166 10.1002/pmic.200400832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Jeanclos E. M., Treuil M., Braunewell K.-H., Gundelfinger E. D., Anand R. (2002). The calcium sensor protein visinin-like protein-1 modulates the surface expression and agonist sensitivity of the alpha 4beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277 41872–41878 10.1074/jbc.M206857200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Neff R. A., Berg D. K. (2006). Sequential interplay of nicotinic and GABAergic signaling guides neuronal development. Science 314 1610–1613 10.1126/science.1134246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozada A. F., Wang X., Gounko N. V., Massey K. A., Duan J., Liu Z., et al. (2012). Glutamatergic synapse formation is promoted by α7-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 32 7651–7661 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6246-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell L. M., Ferguson S. S. G., Daaka Y., Miller W. E., Maudsley S., Della Rocca G. J., et al. (1999). β -arrestin-dependent formation of β 2 adrenergic receptor-src protein kinase complexes. Science 283 655–661 10.1126/science.283.5402.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure-Begley T. D., Stone K. L., Marks M. J., Grady S. R., Colangelo C. M., Lindstrom J. M., et al. (2013). Exploring the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-associated proteome with iTRAQ and transgenic mice. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 11 218–207 10.1016/j.gpb.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miteva Y. V., Budayeva H. G., Cristea I. M. (2013). Proteomics-based methods for discovery, quantification, and validation of protein-protein interactions. Anal. Chem. 85 749–768 10.1021/ac3033257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell M., Espargaró A., Avilés F. X., Ventura S. (2007). Detection of transient protein-protein interactions by bimolecular fluorescence complementation: the Abl-SH3 case. Proteomics 7 1023–1036 10.1002/pmic.200600966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordman J. C., Kabbani N. (2012). An interaction between α7 nicotinic receptors and a G-protein pathway complex regulates neurite growth in neural cells. J. Cell Sci. 125 5502–5513 10.1242/jcs.110379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulo J. A., Brucker W. J., Hawrot E. (2009). Proteomic analysis of an alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor interactome. J. Proteome Res. 8 1849–1858 10.1021/pr800731z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollok B. (1999). Using GFP in FRET-based applications. Trends Cell Biol. 9 57–60 10.1016/S0962-8924(98)01434-1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quian H., Pipolo L., Thomas W. G. (2001). Association of -arrestin 1 with the type 1A angiotensin II receptor involves phosphorylation of the receptor carboxyl terminus and correlates with receptor internalization. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 15 1706–1719 10.1210/me.15.10.1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani K., Teng Y., Pan Y., Dani J. A., Lindstrom J., García Gras E. A., et al. (2009). UBXD4, a UBX-containing protein, regulates the cell surface number and stability of alpha3-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J. Neurosci. 29 6883–6896 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4723-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallette J., Pons S., Devillers-Thiery A., Soudant M., Prado de Carvalho L., Changeux J.-P., et al. (2005). Nicotine upregulates its own receptors through enhanced intracellular maturation. Neuron 46 595–607 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarramegn V., Muller I., Milon A., Talmont F. (2006). Recombinant G protein-coupled receptors from expression to renaturation: a challenge towards structure. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63 1149–1164 10.1007/s00018-005-5557-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy S. K., Drake M. T., Nelson C. D., Houtz D. A., Xiao K., Madabushi S., et al. (2006). beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281 1261–1273 10.1074/jbc.M506576200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinya T., Osada T., Desaki Y., Hatamoto M., Yamanaka Y., Hirano H., et al. (2010). Characterization of receptor proteins using affinity cross-linking with biotinylated ligands. Plant Cell Physiol. 51 262–270 10.1093/pcp/pcp185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinz A. (2003). Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry for mapping three-dimensional structures of proteins and protein complexes. J. Mass Spectrom. 38 1225–1237 10.1002/jms.559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sot J., Bagatolli L. A., Goñi F. M., Alonso A. (2006). Detergent-resistant, ceramide-enriched domains in sphingomyelin/ceramide bilayers. Biophys. J. 90 903–914 10.1529/biophysj.105.067710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchanek M., Radzikowska A., Thiele C. (2005). Photo-leucine and photo-methionine allow identification of protein-protein interactions in living cells. Nat. Methods 2 261–268 10.1038/nmeth752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. C., McNamee M. G. (1990). Purification of membrane proteins. Methods Enzymol. 182 499–520 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82040-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trakselis M. A., Alley S. C., Ishmael F. T. (2005). Identification and mapping of protein-protein interactions by a combination of cross-linking, cleavage, and proteomics. Bioconjug. Chem. 16 741–750 10.1021/bc050043a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong K., Ikura M. (2001). The use of FRET imaging microscopy to detect protein–protein interactions and protein conformational changes in vivo. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11 573–578 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00249-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilescu J., Guo X., Kast J. (2004). Identification of protein-protein interactions using in vivo cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Proteomics 4 3845–3854 10.1002/pmic.200400856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., DeFrances M. C., Dai Y., Pediaditakis P., Johnson C., Bell A., et al. (2002). A mechanism of cell survival: sequestration of Fas by the HGF receptor Met. Mol. Cell 9 411–421 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00439-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Zhu Y., Heinemann S. F. (2006). Identification of sequence motifs that target neuronal nicotinic receptors to dendrites and axons. J. Neurosci. 26 9780–9793 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0840-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun-Hong Y., Chih-Fan C., Chia-Wei C., Yen-Chung C. (2011). A study of the spatial protein organization of the postsynaptic density isolated from porcine cerebral cortex and cerebellum. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M110.007138. 10.1074/mcp.M110.007138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]