Abstract

Dowling-Degos disease (DDD) is an autosomal-dominant genodermatosis characterized by progressive and disfiguring reticulate hyperpigmentation. We previously identified loss-of-function mutations in KRT5 but were only able to detect pathogenic mutations in fewer than half of our subjects. To identify additional causes of DDD, we performed exome sequencing in five unrelated affected individuals without mutations in KRT5. Data analysis identified three heterozygous mutations from these individuals, all within the same gene. These mutations, namely c.11G>A (p.Trp4∗), c.652C>T (p.Arg218∗), and c.798-2A>C, are within POGLUT1, which encodes protein O-glucosyltransferase 1. Further screening of unexplained cases for POGLUT1 identified six additional mutations, as well as two of the above described mutations. Immunohistochemistry of skin biopsies of affected individuals with POGLUT1 mutations showed significantly weaker POGLUT1 staining in comparison to healthy controls with strong localization of POGLUT1 in the upper parts of the epidermis. Immunoblot analysis revealed that translation of either wild-type (WT) POGLUT1 or of the protein carrying the p.Arg279Trp substitution led to the expected size of about 50 kDa, whereas the c.652C>T (p.Arg218∗) mutation led to translation of a truncated protein of about 30 kDa. Immunofluorescence analysis identified a colocalization of the WT protein with the endoplasmic reticulum and a notable aggregating pattern for the truncated protein. Recently, mutations in POFUT1, which encodes protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, were also reported to be responsible for DDD. Interestingly, both POGLUT1 and POFUT1 are essential regulators of Notch activity. Our results furthermore emphasize the important role of the Notch pathway in pigmentation and keratinocyte morphology.

Main Text

Dowling-Degos disease (DDD [MIM 179850, MIM 615327]) is an autosomal-dominant form of a reticulate pigmentary disorder. This rare genodermatosis was first described by Dowling and Freudenthal in 19381 and was termed “dermatose reticulée des plis” by Degos and Ossipowski (1954).2 Affected individuals develop a postpubertal reticulate hyperpigmentation that is progressive and disfiguring, and small hyperkeratotic dark-brown papules that affect the flexures, large skin folds, trunk, face, and extremities. Pruritus and/or burning sensations might also feature in clinical presentations.3 The phenotype can be triggered in some individuals by UV light, mechanical stimulation, or sweating. Histology shows filiform epithelial downgrowth of epidermal rete ridges, with a concentration of melanin at the tips.4 No effective therapy is yet available.

In 2006, we identified loss-of-function mutations in KRT5 (MIM 148040) encoding keratin 5, in two large German families, additional familial cases, and several simplex cases.4 Additional mutations in KRT5 responsible for DDD were also reported.5–8 In subsequent years, we screened more than 40 individuals with DDD and found KRT5 mutations in fewer than 50%, with only 16 simplex and familial cases.9,10 Thus, the causes of a large number of unsolved cases of DDD remain to be explained. In some individuals with DDD, who had originally been diagnosed with Galli-Galli disease (GGD), the additional histopathological feature of acantholysis was observed. The clinical presentation and the genetic backgrounds of these individuals indicated that GGD is a variant of DDD and not a distinct disease entity.6,10,11 Another locus for DDD was identified in an affected Chinese family; this locus is on chromosome 17p13.3, but the responsible mutation has not been identified to date.12 Additionally, recent studies of two Chinese families with DDD led to the identification of mutations in POFUT1 (MIM 607491), which encodes protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 from the Notch pathway.13

Here, we describe the identification of nine different mutations in POGLUT1 (RefSeq accession number NM_152305.2) from 13 unrelated individuals with DDD. POGLUT1 encodes protein O-glucosyltransferase 1 and is a part of the Notch signaling pathway.14,15 Further studies including immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting supported the pathogenicity of the identified mutations.

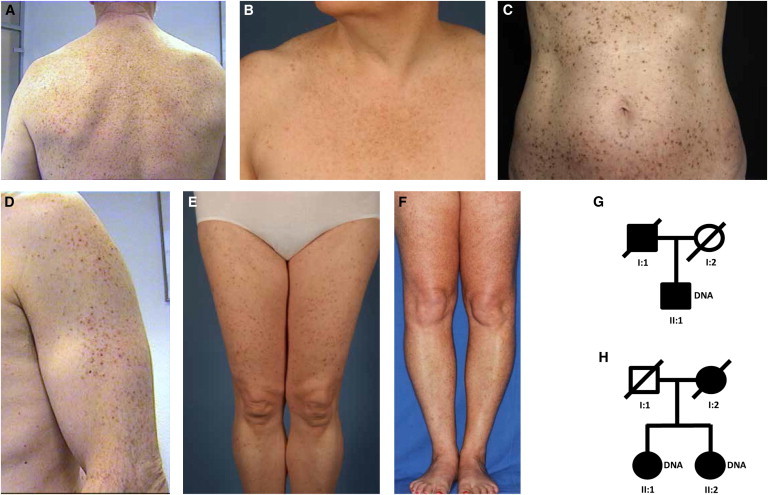

We used the whole-exome sequencing technology to identify other genetic causes of DDD. Five unrelated individuals with comparable DDD phenotypes were selected for sequencing under the assumption that any gene harboring rare variants in all individuals might be a DDD candidate. The age of onset in the five individuals varied between 18 and 53 years. These individuals were all described and characterized previously under a distinct clinical subtype suggested for DDD/Galli-Galli disease.9 Specifically, affected individuals presented with a disseminated pattern of brownish macular and lentiginous lesions on the extremities, trunk/back and neck without the typical domination of the flexural folds observed in classical DDD (Figures 1A–1F).9 Among the five selected individuals with DDD, three reported no family history of DDD. One male individual reported that his father was affected by skin abnormalities similar to his own (Figure 1G), and one female individual reported that her sister and probably her mother exhibited skin abnormalities similar to her own (Figure 1H).

Figure 1.

Clinical Appearance and Pedigrees

(A–F) Reticulate hyperpigmentation and hyperkeratotic brown papules on the back (A), breast (B), trunk (C), arm (D), and legs (E and F) of affected individuals.

(G and H) Pedigrees with two affected individuals. Affected family members are shown in black; circles and squares denote females and males, respectively. Both individuals II:1 (G and H) were used for exome sequencing.

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Düsseldorf and the participants provided written informed consent prior to blood sampling. The study was conducted in concordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes according to standard methods.

For whole-exome sequencing, we fragmented 1 μg of DNA with sonication technology (Bioruptor, Diagenode, Liège, Belgium). The fragments were end-repaired and adaptor-ligated, including incorporation of sample index barcodes. After size selection, we subjected a pool of all 5 libraries to an enrichment process with the SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library version 2.0 kit (Roche NimbleGen). The final libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing instrument (Illumina) with a paired-end 2 × 100 bp protocol. This resulted in 6.2−7.3 Gb of mapped sequences (on average 6.8 Gb), a mean coverage of 68–80× (on average 75×) and 30× coverage of 82–86% (on average 84%) of the target sequences. The Varbank pipeline v.2.1 and interface were used for data analysis and filtering (unpublished data, H.T., J.A., and P.N.; see Table S1 available online). The data were filtered for high-quality rare (MAF < 0.005) autosomal variants and attention was focused on genes with the highest burden of functional variants in individuals with DDD.

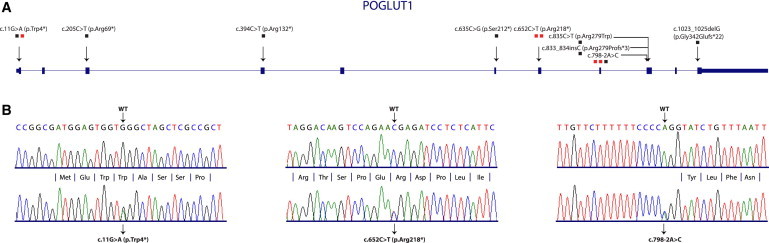

Sequencing data analysis identified a single gene, POGLUT1, which harbors heterozygous nonsense or splice site mutations in all five affected individuals (Figure 2). One of the investigated individuals showed a guanine-to-adenine transition at nucleotide position 11 leading to a stop codon (c.11G>A [p.Trp4∗]). We identified another nonsense mutation in two further individuals at nucleotide position 652 (c.652C>T [p.Arg218∗]; among them individual II:1, Figure 1G). In the remaining two individuals, we identified a mutation at a splice site (c.798-2A>C; among them individual II:1, Figure 1H). The splice site mutation was also identified in the sister of individual II:2 (Figure 1H; data not shown). All three variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and an ABI 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Position of Mutations in POGLUT1 and Verification of Mutations Identified by Exome Sequencing

(A) Cartoon depicting the exon structure of POGLUT1. All identified mutations are marked by arrow heads. The mutations are defined on nucleotide and protein levels. The number of individuals carrying each mutation is denoted with the number of squares. Red squares indicate mutations identified by exome sequencing.

(B) All three mutations identified by exome sequencing were verified by Sanger sequencing. The mutated sequences are given in comparison to WT sequences.

In addition, we screened further individuals from our DDD cohort for mutations in POGLUT1. Primer sequences for amplification of POGLUT1 exons are listed in the supplemental information (Table S2). We identified c.11G>A in a single person, c.798-2A>C in a single person, and additional mutations in six individuals (Table 1; Figure 2A; Figure S1). One of these mutations, c.394C>T (p.Arg132∗), which leads to a premature stop codon, is reported in the 1000 Genomes database as the variant rs140695299 with a frequency of 1 in 1,092 individuals. Due to the low incidence frequency and the late age of onset of the disease, it is likely that this mutation and two further very rare (combined MAF < 0.0002) frameshift and splice site mutations (c.898 del1 [p.Phe300Serfs∗6] and c.1023-2A>C, respectively) reported in databases also lead to the hyperpigmentation disorder, and that DDD might be more common than reported. None of the other identified mutations were found in dbSNP137, ESP, or 1000 Genomes databases. Unfortunately, mostly as a result of the late age of onset of the disease, it was not possible to get blood samples from any parents of our individuals or any affected children. In total, we identified nine different heterozygous mutations in a total of 13 individuals with DDD, including nonsense, splice site, missense, insertion, and deletion mutations. We therefore suggest that POGLUT1 is a gene, mutations in which are responsible for DDD. Of note, one of the nonsense mutations is located at the very beginning of the protein (p.Trp4∗). Therefore, it is very likely that the mRNA transcript with this mutation is affected by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay making haploinsufficiency the most plausible mechanism for autosomal-dominant inheritance.

Table 1.

POGLUT1 Mutations Identified in 13 Individuals with DDD

| Mutation | Protein Alteration | Number of Individuals | Origin of the Individuals | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.11G>A | p.Trp4∗ | 2 | Germany, Denmark | Hanneken et al., 2011 This study |

| c.205C>T | p.Arg69∗ | 1 | Switzerland | This study |

| c.394C>T | p.Arg132∗ | 1 | Germany | This study |

| c.635C>G | p.Ser212∗ | 1 | Germany | This study |

| c.652C>T | p.Arg218∗ | 2 | Germany | Hanneken et al., 2011 |

| c.798-2A>C | - | 3 | Germany | Hanneken et al., 2011 |

| c.833_834insC | Arg279Profs∗3 | 1 | Germany | Mauerer et al., 201042 |

| c.835C>T | p.Arg279Trp | 1 | Germany | This study |

| c.1023_1025delG | p.Gly342Glufs∗22 | 1 | Germany | This study |

Of interest, the observation of prominent involvement of nonflexural areas in individuals with POGLUT1 mutations in comparison to the individuals with KRT5 mutations who present with typical domination of the flexural folds9 is suggestive of a correlation between the gene in which mutations are harbored and the DDD phenotype displayed by the affected individuals.

POGLUT1 is located on chromosome 3q13.33 and has a 1.179 bp open reading frame consisting of 11 coding exons.16 POGLUT1 encodes the 392 amino acid protein POGLUT1, alternatively termed KTELC1, C3orf9, hCLP46, and Rumi, among others. POGLUT1 constitutes protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, which adds O-linked glucose to the epidermal growth factor-like (EGF) repeats of Notch receptors.15,17,18

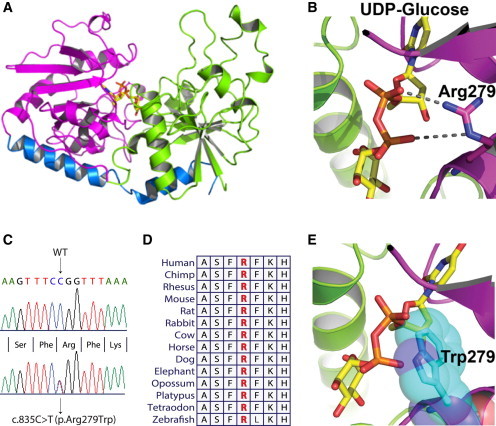

The mutations identified in our individuals with DDD are predicted to have a major impact on the translation or the structure of POGLUT1. POGLUT1 is orthologous to several other structurally well-characterized glucosyltransferases from viruses or bacteria. The effects of the different POGLUT1 mutations on the resultant protein were predicted on the basis of a homology model (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3E; Figure S2). A model of POGLUT1 was generated with Modeler.19–22 Alignments of POGLUT1 with sequences of template structures were generated with the HHPred server.23 The model was manually adjusted with Coot24 and figures were generated with PyMol.25 As in orthologous glucosyltransferases, POGLUT1 is composed of an N-terminal (residues 1–180) and a C-terminal (residues 181–392) domain that together form a large binding pocket for the substrate UDP-glucose at the domain interface (Figure 3A). The arrangement of the two domains is stabilized by a long C-terminal helix, whereby the C-terminal end of the helix is anchored in the N-terminal domain. The mutations causing a translation stop lead to truncated variants of POGLUT1 that lack major parts or essential residues resulting in the loss of the substrate binding site (Figure S2). The truncated form p.Arg132∗ is missing parts of the N-terminal domain as well as the entire C-terminal domain. The mutants p.Ser212∗ and p.Arg218∗, as well as p.Arg279Profs∗3, lack parts of the substrate-binding site essential for high-affinity binding of UDP-glucose. p.Gly342Glufs∗22 is missing in part the long C-terminal helix causing most likely a disassembly of the N- and C-terminal domains (Figure S2). We analyzed the effects of the splice site mutation c.798-2A>C by total RNA isolation from the mutation carrier individual followed by reverse transcription of total mRNA into cDNA and POGLUT1 sequencing. We showed that this mutation leads to abolishment of exon 9, which would result in loss of residues 267–322 in the translated protein (Figure S3). This large deletion will abolish correct folding of the C-terminal domain of POGLUT1. Moreover, a number of residues forming the substrate binding site will be missing, and therefore we anticipate that this mutant is also inactive. The p.Arg279Trp substitution (Figure 3C) leads to the replacement of a highly conserved arginine (Figure 3D) with the dissimilar amino acid tryptophan. The homology model revealed that Arg279 is particularly involved in binding the UDP-glucose substrate. In the orthologous glucosyltransferase of T4 phage, the guanidinium group of the corresponding arginine residue forms two salt bridges with the diphosphate moiety of UDP-glucose and is required to bind the substrate with high affinity.26,27 In the homology model, Arg279 can adopt a similar conformation to bind UDP-glucose (Figure 3B). Substitution by tryptophan disrupts the interaction with the substrate and, moreover, the bulky side chain of tryptophan might hinder access of the substrate to the binding site (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Protein Modeling of Wild-Type and Mutant POGLUT1

(A) POGLUT1 is composed of two major domains; the N-terminal domain (residues 1–180; green) and the C-terminal domain (residues 181–349; magenta) together form a binding pocket for the substrate UDP-glucose (stick model; yellow) at the domain interface. A long C-terminal helix (residues 350–384; blue) stabilizes the arrangement of the two domains.

(B) Arg279 is critically involved in UDP-glucose binding forming two salt bridges to oxygen atoms of the diphosphate moiety of UDP-glucose. UDP-glucose is shown as stick model with carbon shown in yellow, nitrogen in blue, phosphor in orange, and oxygen in red. Arg279 is shown as stick model with carbon in magenta and nitrogen atoms in blue. The salt bridges are indicated as broken lines.

(C) Sequence analysis showing the mutant and WT sequences for the missense mutation leading to substitution of an arginine residue with tryptophan (c.835C>T [p.Arg279Trp]).

(D) Partial amino acid sequence of human POGLUT1 in comparison with orthologs from other species. Arginine residue depicted with red is highly conserved across different species.

(E) p.Arg279Trp leads to the substitution of this arginine residue with tryptophan. Loss of the interaction between arginine and the phosphate group of UDP-glucose will largely decrease the affinity to the substrate. Moreover, the large side chain of Trp279 in the mutant form of the enzyme might block the access of UDP-glucose. The side chain of Trp279 is shown as stick model and Van-der-Waals spheres in cyan.

To analyze the localization pattern of POGLUT1, we investigated skin biopsies from healthy and affected individuals by using immunohistochemistry. Sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded skin biopsies obtained by plastic surgery from four individuals with DDD and different POGLUT1 mutations (nonsense and splice site) and from four healthy controls with normal skin. Standard H&E and periodic acid-Schiff staining was performed for diagnostic purposes. POGLUT1 localization was analyzed using polyclonal anti-POGLUT1 antibody. Results were evaluated on blinded specimens by an experienced dermatopathologist (J.W.) as described previously.28

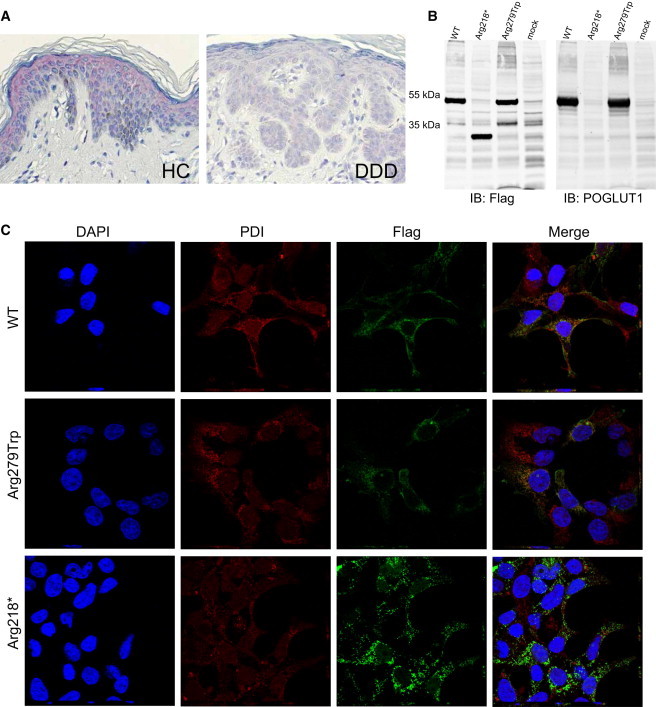

Histologically, skin lesions from individuals with DDD showed a digitiform reteacanthosis with pronounced hyperpigmentation at the tips of the rete ridges, some small horn cysts, minor acantholysis, and focal hypergranulosis (Figure S4). In immunohistology, we found POGLUT1 to be prominently present in the epidermis of healthy controls, especially in the upper parts (stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum, Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry on Skin Biopsies, Immunoblotting, and Immunofluorescence Analysis of HEK293T cells Transiently Expressing Wild-Type and Mutant POGLUT1

(A) For immunohistochemistry, sections were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded skin biopsies obtained by plastic surgery from individuals with DDD and healthy controls. POGLUT1 localization was analyzed with the polyclonal antibody NBP1-90311 (named KTELC1; Novus Biologicals) at a 1:500 dilution. Visualization was performed with the LSAB2 staining kit (DAKO) with Fast Red Chromogen.

POGLUT1 was strongly present in the epidermis of healthy controls, especially in the upper parts (the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum). POGLUT1 staining was weaker in lesional skin of individuals affected by DDD.

(B) For immunoblotting, WT sequence, sequence bearing mutation c.652C>T (p.Arg218∗), and sequence bearing mutation c.835C>T (p.Arg279Trp) were cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pAAV-CMV-MCS (Stratagene). HEK293T cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures [ECACC]) were transiently transfected with the plasmids by the use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hr after transfection, cells were lysed in ice cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with proteinase inhibitors (Roche) for 30 min on ice followed by sonication and centrifugation at 14.000 rpm/10 min/4°C. Clear supernatant was boiled with SDS-sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min and the proteins were subjected to gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 10%) followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore). Immunoblotting was performed with mouse anti-Flag (1804; Sigma Aldrich, 1:1.000), rabbit anti-POGLUT1 (NBP1-90311; Novus Biologicals, 1:1.000) primary antibodies and IRDye secondary antibodies (IRDye 800 goat anti-mouse and IRDye 680 goat anti-rabbit, 1:10.000). Bands of the expected size were detected for the WT POGLUT1 and the protein with the p.Arg279Trp substitution, whereas the nonsense mutation (c.652C>T [p.Arg218∗]) led to translation of a truncated protein of around 30 kDa.

(C) Immunofluorescence analysis was performed with transiently transfected HEK293T cells. Cells were fixed and incubated for 12–14 hr with mouse anti-Flag (1:400, Sigma-Aldrich) and rabbit anti-PDI (1:200, Abcam) antibodies. After several washing steps, cells were incubated for 40 min with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit, Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse (1:300, Invitrogen), and DAPI (Invitrogen).

Images were acquired at room temperature with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Nikon A1/Ti, Nikon) with a CFI Plan Apochromat infrared 60× water-immersion objective (NA 1.27). For each construct z stack (step: 0.250 um), images were taken with the NIS-Elements 4.0 acquisition software (Nikon).

The analysis revealed the colocalization of the WT POGLUT1 with endoplasmic reticulum (ER). No significant difference was observed in localization patterns of the WT protein and the protein with the amino acid substitution. However, a more aggregated pattern was observed for the truncated protein in comparison to the WT protein, which coincided with an impaired colocalization with the ER. Abbreviations are as follows: HC, healthy control; DDD, Dowling-Degos disease, IB, immunoblot.

The strong POGLUT1 staining in the matured parts of the epidermis might be indicative that POGLUT1 is important for the correct differentiation of the epidermal layer and might emphasize an important role for POGLUT1 in the development of the epidermis. On the other hand, POGLUT1 staining was about 50% weaker in lesional skin of individuals with DDD in comparison to healthy controls (mean staining intensity, 1.75 ± 0.25 SEM versus 0.75 ± 0.32 SEM, p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney U-test) (Figure 4A; Figure S5). This observation could be due to only the WT POGLUT1 being detected by the antibody and not the truncated forms. This would be in accordance with the affected individuals having only one copy of the gene encoding for the WT protein. We next examined whether the mutated gene variants produce full-length, truncated, or no POGLUT1. For this purpose, POGLUT1, WT, and two of the identified mutants (p.Arg218∗ and p.Arg279Trp) were fused to N- and C-terminal Strep/FLAG Tandem Affinity-tags (N-TAP and C-TAP constructs, respectively) and expressed in HEK293T cells (European Collection of Cell Cultures [ECACC]) and analyzed by immunoblotting. Primers used for cloning and mutagenesis are listed in the supplemental information (Tables S3 and S4). Immunoblot analysis showed that the WT construct led to translation of a protein of about 50 kDa in size, which is in accordance with previous reports.16 While the missense mutation did not alter the molecular weight, the nonsense mutation resulted in a truncated protein of about 30 kDa in size (Figure 4B). There were no significant differences in the molecular weights between the N-TAP and C-TAP tagged proteins (Figure S6). The immunoblot labeled with anti-POGLUT1 antibody confirmed the translation of the targeted proteins (Figure 4B; Figure S6).

To determine the subcellular localization of WT and mutant POGLUT1, we performed immunofluorescence analysis with transiently transfected HEK293T cells. The confocal microscopy analyses revealed the colocalization of the WT POGLUT1 with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for both the N- and C-TAP constructs (Figure 4C; Figure S7) as previously reported in COS7 cells.16 No significant difference was observed in the subcellular localization of the WT protein and the protein with the p.Arg279Trp substitution in either of the constructs (Figure 4C; Figure S7). However, compared to the WT proteins, the truncated N-TAP-POGLUT1 appeared to form more aggregates, which coincided with an impaired colocalization with the ER (Figure 4C). This can be explained by the lack of the C-terminal tetrapeptide sequence KTEL, which is known to be important for the retention of POGLUT1 in the ER.16 In addition, the stabilizing effect of the C-terminal helix as shown by homology modeling of POGLUT1 (Figure 3A) might influence the protein conformation and thus its subcellular localization. In the C-TAP constructs, however, we did not observe any significant difference in the localization of the WT and the truncated proteins (Figure S7). The difference between the two constructs can be attributed to the position of the tag. In the C-TAP constructs the amino acid sequence in the vicinity of the tag is different between the WT and the truncated forms, whereas it is the same in the N-TAP constructs.

POGLUT1 is part of the Notch signaling pathway, which is important for cell fate and tissue formation during embryogenesis and, in adulthood, for differentiation and stem cell maintenance. Mutations have been found in various genes of the Notch signaling pathway, including those encoding receptors and ligands, and have been shown to cause diverse disorders such as cerebral arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL [MIM 125310]),29 spondylocostal dysostosis (SCDO1 [MIM 277300]),30 Alagille syndrome (ALGS1 [MIM 118450], ALGS2 [MIM 610205]),31,32 Adams-Oliver syndrome (AOS3 [MIM 614814]), and diverse cardiac disorders and carcinomas.

Besides its role in important developmental processes, the Notch pathway also plays an important role in skin homeostasis by regulating the proliferation and differentiation dynamics of melanocytes and keratinocytes.33–35 Notch signaling is also suggested to be a key component in mediating the interactions between melanocytes and keratinocytes.36–38 This is consistent with our former4 observations of the irregular shape and size of keratinocytes in skin biopsies of individuals with DDD. In addition, we previously reported a haphazard distribution of irregularly shaped melanosomes as determined by ultrastructural analysis in individuals affected by DDD with KRT5 mutations.4 Of note, KRT5 is together with KRT14 (MIM 148066) known to be required for normal development of the basal cells in the epidermis. Loss of KRT5 and KRT14 expression during epidermal differentiation coincides with increased levels of activated Notch1 in these cells.39 By immunohistochemistry we also investigated KRT5 in skin biopsies of POGLUT1 mutation carriers affected by DDD in comparison to normal skin and skin from individuals with psoriasis as a positive control. As expected, KRT5 staining was weak and mostly restricted to the basal epidermal layer in healthy controls (Figure S8). On the other hand, KRT5 was prominently present within the whole epidermal layer in psoriasis, which is a disease characterized by disturbed epidermal differentiation. Interestingly, KRT5 was also strongly present within the lesional DDD skin, not only in the basal epidermal areas but also in upper parts of the epidermis, which might suggest a disturbed epidermal differentiation in DDD (Figure S8). This would also be in accordance with effects of Notch pathway on keratinocyte differentiation.

Notch deficiencies leading to abnormal pigmentation have been previously noted. For example, mice depleted of Notch1 (MIM 190198) and Notch2 (MIM 600275) receptors exhibit a progressive and precocious hair graying.36,38 In another example, mice with a conditionally ablated recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region (RBPJ [MIM 147183]), which encodes a transcriptional regulator of the Notch signaling pathway, presented with abnormal pigmentation in the dermal papilla;35,37 this might be considered analogous to the hyperpigmentation phenotype displayed by our individuals affected by DDD. This abnormal pigmentation in mice is attributed to a lack of Notch signaling, leading to aberrant migration of melanoblasts and melanocytes to ectopic locations.35 These observations, alongside our data presented here and elsewhere, suggest that deleterious mutations in POGLUT1 encoding protein O-glucosyltransferase, lead to a disorder with abnormalities in pigmentation and keratinocyte morphology.

Fernandez-Valdivia et al. (2011) reported dominant and recessive Rumi (POGLUT1) mice mutants.15 The Rumi−/− recessive knockouts died before embryonic day 9.5 and showed severe defects in neural tube development, somitogenesis, cardiogenesis, and vascular remodeling. It was also shown that Jag1+/−, Rumi+/− double-heterozygous animals showed bile duct defects. Heterozygotes with loss of one copy of Rumi resulted in 50% loss of POGLUT1 activity.15 The heterozygotes did not display any clearly aberrant skin phenotype,15 but it is possible that mild alterations to pigmentation would not have been observed.

A recent report by Li et al. (2013) identified mutations in POFUT1 as being responsible for DDD.13 POGLUT1 and POFUT1 are both involved in posttranslational modification of Notch proteins. POFUT1 adds O-linked fucose to EGF-like repeats of Notch receptors, whereas POGLUT1 transfers O-linked glucose from UDP-glucose to serine residues in Notch EGF repeats with the consensus C1-X-S-X-P-C2.18 Li et al. identified a nonsense mutation and a single base pair deletion mutation in Chinese individuals in POFUT1.13 Additional functional studies performed by the Chinese group, such as morpholino knockdown and knockdown of POFUT1 in HaCat cells, strongly suggest that POFUT1 is involved in melanin synthesis.13

Another recent study used whole-exome sequencing to identify mutations in ADAM10 (MIM 602192) encoding a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 10 as the cause of another hyperpigmentation disorder, reticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura (RAK).39 Hyperpigmentation in RAK is mainly concentrated in the dorsa of the hand and feet, but it has nevertheless been posited that DDD and RAK overlap. ADAM10 is another key protein in the Notch signaling pathway and is required for the activation of NOTCH1 through a proteolytic mechanism initiated by ligand-binding.40,41

In summary, the identification of DDD causative mutations in POGLUT1, encoding protein O-glucosyltransferase 1, contributes to the growing list of genes that, when mutated, are known to be responsible for human hyperpigmentation disorders. Our results, in combination with data describing the effects of mutations in POFUT1, contribute to a better understanding of the biology of the skin and emphasize the important role of the Notch pathway in pigmentation and differentiation of the epidermis.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the individuals and families for participating in this study. We thank Lodovica Borghese for fruitful discussions. This work was further supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) to S.S. (SFB-1089/A1, P2) and the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Federal Ministry of Education and Research) to S.S. (“Unabhängige Forschergruppen in den Neurowissenschaften”), as well as by local funding (BONFOR to S.S. and R.C.B.). G.F. is a recipient of a Heisenberg Fellowship (FR 1488/3-2) and R.C.B. is a recipient of a Heisenberg Professorship of the German Research Foundation (DFG) (BE 2346/4-1). P.N. is a founder, CEO, and shareholder of ATLAS Biolabs GmbH. ATLAS Biolabs GmbH is a service provider for genomic analyses.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes, http://browser.1000genomes.org

NCBI Blast & Align: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org/

UCSC Human Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway

Varbank Exome Pipeline and Filtering: https://anubis.ccg.uni-koeln.de/varbank/

References

- 1.Dowling G.B., Freudenthal W. Acanthosis Nigricans. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1938;31:1147–1150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Degos R., Ossipowski B. Dermatose pigmentaire ŕeticulée des plis (discussion de l’acanthosis nigricans) Ann. Dermatol. Syphiligr. (Paris) 1954;81:147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilchrist H., Jackson S., Morse L., Nicotri T., Nesbitt L.T. Galli-Galli disease: A case report with review of the literature. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Betz R.C., Planko L., Eigelshoven S., Hanneken S., Pasternack S.M., Bussow H., Van Den Bogaert K., Wenzel J., Braun-Falco M., Rütten A. Loss-of-function mutations in the keratin 5 gene lead to Dowling-Degos disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:510–519. doi: 10.1086/500850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo L., Luo X., Zhao A., Huang H., Wei Z., Chen L., Qin S., Shao L., Xuan J., Feng G. A novel heterozygous nonsense mutation of keratin 5 in a Chinese family with Dowling-Degos disease. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012;26:908–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sprecher E., Indelman M., Khamaysi Z., Lugassy J., Petronius D., Bergman R. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007;156:572–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao H., Zhao Y., Baty D.U., McGrath J.A., Mellerio J.E., McLean W.H. A heterozygous frameshift mutation in the V1 domain of keratin 5 in a family with Dowling-Degos disease. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2007;127:298–300. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnold A.W., Kiritsi D., Happle R., Kohlhase J., Hausser I., Bruckner-Tuderman L., Has C., Itin P.H. Type 1 segmental Galli-Galli disease resulting from a previously unreported keratin 5 mutation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012;132:2100–2103. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanneken S., Rütten A., Eigelshoven S., Braun-Falco M., Pasternack S.M., Ruzicka T., Nöthen M.M., Betz R.C., Kruse R. [Galli-Galli disease. Clinical and histopathological investigation using a case series of 18 patients] Hautarzt. 2011;62:842–851. doi: 10.1007/s00105-011-2222-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanneken S., Rütten A., Pasternack S.M., Eigelshoven S., El Shabrawi-Caelen L., Wenzel J., Braun-Falco M., Ruzicka T., Nöthen M.M., Kruse R., Betz R.C. Systematic mutation screening of KRT5 supports the hypothesis that Galli-Galli disease is a variant of Dowling-Degos disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010;163:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmieder A., Pasternack S.M., Krahl D., Betz R.C., Leverkus M. Galli-Galli disease is an acantholytic variant of Dowling-Degos disease: additional genetic evidence in a German family. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;66:e250–e251. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C.R., Xing Q.H., Li M., Qin W., Yue X.Z., Zhang X.J., Ma H.J., Wang D.G., Feng G.Y., Zhu W.Y., He L. A gene locus responsible for reticulate pigmented anomaly of the flexures maps to chromosome 17p13.3. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2006;126:1297–1301. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li M., Cheng R., Liang J., Yan H., Zhang H., Yang L., Li C., Jiao Q., Lu Z., He J. Mutations in POFUT1, Encoding Protein O-fucosyltransferase 1, Cause Generalized Dowling-Degos Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma W., Du J., Chu Q., Wang Y., Liu L., Song M., Wang W. hCLP46 regulates U937 cell proliferation via Notch signaling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;408:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Valdivia R., Takeuchi H., Samarghandi A., Lopez M., Leonardi J., Haltiwanger R.S., Jafar-Nejad H. Regulation of mammalian Notch signaling and embryonic development by the protein O-glucosyltransferase Rumi. Development. 2011;138:1925–1934. doi: 10.1242/dev.060020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teng Y., Liu Q., Ma J., Liu F., Han Z., Wang Y., Wang W. Cloning, expression and characterization of a novel human CAP10-like gene hCLP46 from CD34(+) stem/progenitor cells. Gene. 2006;371:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeuchi H., Fernández-Valdivia R.C., Caswell D.S., Nita-Lazar A., Rana N.A., Garner T.P., Weldeghiorghis T.K., Macnaughtan M.A., Jafar-Nejad H., Haltiwanger R.S. Rumi functions as both a protein O-glucosyltransferase and a protein O-xylosyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:16600–16605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109696108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Acar M., Jafar-Nejad H., Takeuchi H., Rajan A., Ibrani D., Rana N.A., Pan H., Haltiwanger R.S., Bellen H.J. Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell. 2008;132:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sali A., Blundell T.L. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martí-Renom M.A., Stuart A.C., Fiser A., Sánchez R., Melo F., Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart P.E., Hüffmeier U., Nair R.P., Palla R., Tejasvi T., Schalkwijk J., Elder J.T., Reis A., Armour J.A. Association of β-defensin copy number and psoriasis in three cohorts of European origin. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012;132:2407–2413. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M.A., Madhusudhan M.S., Eramian D., Shen M.Y., Pieper U., Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2006;Chapter 5 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0506s15. Unit 5 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Söding J., Biegert A., Lupas A.N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W244–W248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrödinger, L.L.C. (2010). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3r1. In.

- 26.Moréra S., Imberty A., Aschke-Sonnenborn U., Rüger W., Freemont P.S. T4 phage beta-glucosyltransferase: substrate binding and proposed catalytic mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:717–730. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moréra S., Larivière L., Kurzeck J., Aschke-Sonnenborn U., Freemont P.S., Janin J., Rüger W. High resolution crystal structures of T4 phage beta-glucosyltransferase: induced fit and effect of substrate and metal binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:569–577. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wenzel J., Wörenkämper E., Freutel S., Henze S., Haller O., Bieber T., Tüting T. Enhanced type I interferon signalling promotes Th1-biased inflammation in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J. Pathol. 2005;205:435–442. doi: 10.1002/path.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joutel A., Corpechot C., Ducros A., Vahedi K., Chabriat H., Mouton P., Alamowitch S., Domenga V., Cécillion M., Marechal E. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature. 1996;383:707–710. doi: 10.1038/383707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulman M.P., Kusumi K., Frayling T.M., McKeown C., Garrett C., Lander E.S., Krumlauf R., Hattersley A.T., Ellard S., Turnpenny P.D. Mutations in the human delta homologue, DLL3, cause axial skeletal defects in spondylocostal dysostosis. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:438–441. doi: 10.1038/74307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDaniell R., Warthen D.M., Sanchez-Lara P.A., Pai A., Krantz I.D., Piccoli D.A., Spinner N.B. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:169–173. doi: 10.1086/505332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oda T., Elkahloun A.G., Pike B.L., Okajima K., Krantz I.D., Genin A., Piccoli D.A., Meltzer P.S., Spinner N.B., Collins F.S., Chandrasekharappa S.C. Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;16:235–242. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okuyama R., Tagami H., Aiba S. Notch signaling: its role in epidermal homeostasis and in the pathogenesis of skin diseases. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008;49:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rangarajan A., Talora C., Okuyama R., Nicolas M., Mammucari C., Oh H., Aster J.C., Krishna S., Metzger D., Chambon P. Notch signaling is a direct determinant of keratinocyte growth arrest and entry into differentiation. EMBO J. 2001;20:3427–3436. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aubin-Houzelstein G., Djian-Zaouche J., Bernex F., Gadin S., Delmas V., Larue L., Panthier J.J. Melanoblasts’ proper location and timed differentiation depend on Notch/RBP-J signaling in postnatal hair follicles. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2008;128:2686–2695. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumano K., Masuda S., Sata M., Saito T., Lee S.Y., Sakata-Yanagimoto M., Tomita T., Iwatsubo T., Natsugari H., Kurokawa M. Both Notch1 and Notch2 contribute to the regulation of melanocyte homeostasis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2008;21:70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moriyama M., Osawa M., Mak S.S., Ohtsuka T., Yamamoto N., Han H., Delmas V., Kageyama R., Beermann F., Larue L., Nishikawa S. Notch signaling via Hes1 transcription factor maintains survival of melanoblasts and melanocyte stem cells. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:333–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schouwey K., Delmas V., Larue L., Zimber-Strobl U., Strobl L.J., Radtke F., Beermann F. Notch1 and Notch2 receptors influence progressive hair graying in a dose-dependent manner. Dev. Dyn. 2007;236:282–289. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alam H., Sehgal L., Kundu S.T., Dalal S.N., Vaidya M.M. Novel function of keratins 5 and 14 in proliferation and differentiation of stratified epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:4068–4078. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeuchi H., Haltiwanger R.S. Role of glycosylation of Notch in development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bozkulak E.C., Weinmaster G. Selective use of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in activation of Notch1 signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:5679–5695. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00406-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mauerer A., Betz R.C., Pasternack S.M., Landthaler M., Hafner C. Generalized solar lentigines in a patient with a history of radon exposure. Dermatology. 2010;221:206–210. doi: 10.1159/000316091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.