Abstract

Rationale

Deregulated vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation contributes to multiple vascular pathologies, and Notch signaling regulates VSMC phenotype.

Objective

Previous work focused on Notch1 and Notch3 in VSMC during vascular disease; however, the role of Notch2 is unknown. Because injured murine carotid arteries display increased Notch2 in VSMC as compared to uninjured arteries, we sought to understand the impact of Notch2 signaling in VSMC.

Methods and Results

In human primary VSMC, Jagged-1 (Jag-1) significantly reduced proliferation through specific activation of Notch2. Increased levels of p27kip1 were observed downstream of Jag-1/Notch2 signaling, and required for cell cycle exit. Jag-1 activation of Notch resulted in increased phosphorylation on serine 10, decreased ubiquitination and prolonged half-life of p27kip1. Jag-1/Notch2 signaling robustly decreased S-phase kinase associated protein (Skp2), an F-box protein that degrades p27kip1 during G1. Over expression of Skp2 prior to Notch activation by Jag-1 suppressed the induction of p27kip1. Additionally, increased Notch2 and p27kip1 expression was co-localized to the non-proliferative zone of injured arteries as indicated by co-staining with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), whereas Notch3 was expressed throughout normal and injured arteries, suggesting Notch2 may negatively regulate lesion formation.

Conclusions

We propose a receptor specific function for Notch2 in regulating Jag-1-induced p27kip1 expression and growth arrest in VSMC. During vascular remodeling, co-localization of Notch2 and p27kip1 to the non-proliferating region supports a model where Notch2 activation may negatively regulate VSMC proliferation to lessen the severity of the lesion. Thus Notch2 is a potential target for control of VSMC hyperplasia.

Keywords: Smooth muscle cell, Notch receptor, proliferation, neointima, neointimal hyerplasia

INTRODUCTION

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) exhibit tremendous phenotype plasticity in response to injury, remodeling, sheer stress and other environmental cues1. VSMC express contractile proteins necessary for maintaining vessel tone and function, including alpha smooth muscle actin (SM actin), calponin1, SM22α, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain and smoothelin B. In response to vascular injury, VSMC down regulate contractile proteins and begin proliferating and migrating in response to secreted cytokines potentially leading to the development and progression of neointimal hyperplasia, pulmonary hypertension, and other vascular diseases2.

An intact Notch pathway is critical for normal vascular development and remodeling in response to vascular pathology3. Notch3 was characterized as a major regulator of VSMC development4 and is mutated in human CADASIL5. We now understand that signaling through Notch2 and Notch1 also activate pathways required during embryonic vascular development and vascular repair. For example, mice with a homozygous hypomorphic mutation in Notch2 undergo abnormal development of the heart and eye vasculature6 and Notch2 has been implicated in the development of aortic smooth muscle7. Both Notch2 and Notch3 are required for normal VSMC development during embryogenesis where they play compensatory, yet non-overlapping roles8. Several reports have investigated potential functions of Notch or Jagged-1 (Jag-1) in neointimal lesion formation during pathological remodeling in response to injury9 and demonstrated their regulation of VSMC phenotype. Interestingly, though, there have not been unique signaling functions identified downstream of Notch1, Notch2, or Notch3 in VSMC.

Our work using human VSMC identifies a novel, Notch2-specific signaling role in the regulation of VSMC proliferation. Although human VSMC additionally express Notch1 and Notch3, and all can interact with Jag-1, only Notch2 signals to mediate cell cycle exit. We propose that this specific cell cycle regulatory pathway mediated by Jag-1 interaction with Notch2 is an important negative regulatory mechanism to prevent excessive VSMC proliferation in injured arteries.

METHODS

An expanded methods section is available in the online supplement.

Surgical procedures

All mouse studies were performed with strict adherence to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Maine Medical Center. For the arterial ligation model, 8 week old FVB male mice were subjected to common carotid artery ligation10. Control mice received a sham operation. Carotid arteries were collected after 14 days.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded mouse carotid arteries were cut into 5μm sections immediately adjacent to the site of injury. Sections were rehydrated and antigen retrieval performed using citric acid buffer and heat, permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes and blocked for 2h in solution of 2% BSA and 2% goat serum. Antibodies against Notch1, Notch2, Notch3, p27kip1 (Cell Signaling), PCNA (Santa Cruz), SM-actin (Sigma) or CD31 (Abcam) were diluted 1:200–1:500 and incubated with sections overnight at 4°C. After washing in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.01% tween-20 (TBS-T, pH=7.4), sections were either incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 2h, reacted with diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin or incubated with Alexa-fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) for 2h, washed with TBS-T, counterstained with DAPI and coverslipped.

Cell culture

Human primary aortic VSMC (Lonza) were used between passages 5 to 7. Human pulmonary arterial VSMC and coronary artery VSMC (Lonza) were used at passage 5. To activate Notch, VSMC were plated on dishes pre-coated with 3μg recombinant rat Jag-1 fused to human Fc (R&D Systems) or with a human Fc control protein (Millipore) as described11, 12. Small interfering RNAs or scrambled control (Qiagen) were transfected into VSMC using the Amaxa nucleofector12.

Cell cycle analysis

Human aortic VSMC were harvested by trypsinization, spun down and washed in PBS before resuspension in ice-cold 70% ethanol and incubation at −20°C overnight. The next day, the cells were centrifuged, washed in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in MUSE cell cycle reagent (Millipore), a propidium iodide-based staining kit compatible with the MUSE cell analyzer. DNA content was analyzed using the MUSE cell analyzer.

Statistical analysis

F-scores were generated for experiments containing multiple comparisons using ANOVA. Student’s two tailed t-test was used for pairwise analysis. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Notch2 expression is increased in VSMC of remodeling arteries

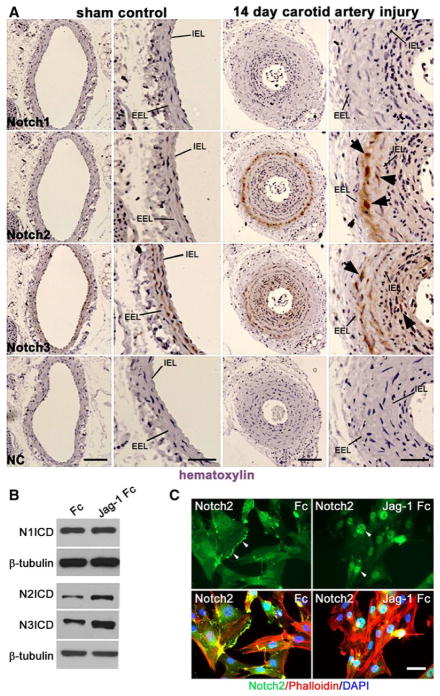

To determine the levels of Notch receptors in VSMC of normal and injured vessels, we utilized the carotid artery ligation model as a reproducible means to generate neointimal lesion formation10. Carotid arteries from 8 week old FVB male mice were studied 14 days following left carotid artery ligation or sham surgery. Expression of Notch3 was localized to the media of sham arteries, while Notch1 and Notch2 were undetectable (Fig. 1A, left columns). Consistent with previous studies13, vascular injury resulted in robust up regulation of Notch2 predominantly localized to the medial VSMC (arrowheads). Notch3 expression was high in both the medial and neointimal VSMC, whereas Notch1 was marginally elevated 14d after vascular injury (Fig. 1A, right columns). Cells with increased Notch2 protein in the ligated artery were also positive for smooth muscle actin and SM22α, markers of VSMC (data not shown). This expression pattern in injured arteries suggests an enhanced function for Notch2 in response to vascular remodeling.

Figure 1. Notch2 is produced in remodeling VSMC, and responsive to Jag-1 ligand.

A) Immunohistochemical analysis of Notch1, Notch2, or Notch3 receptors in sham control and injured murine carotid arteries 14 days after ligation. Slides were counter stained with hematoxylin. NC=non-immune control, IEL= internal elastic lamina, EEL=external elastic lamina. Scale bar=100μm for columns 1&3 and 50μm for columns 2&4, n=5 per group. B) Immunoblot of whole cell lysates for the ICD of Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 in human aortic VSMC plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 6h. C) VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 15h and Notch2 was analyzed using immunofluorescence (green). DAPI and phalloidin were used to visualize cell nuclei and actin filaments, respectively. Scale bar=50μm.

Prior studies found that Jag-1 activation of Notch3 in VSMC leads to maturation and quiescence14. To determine if Jag-1 also signals through other Notch receptors, we activated VSMC with recombinant Jag-1 fused to a human Fc domain12 and analyzed whole cell lysates by immunoblot for Notch. Notch1, Notch2 and Notch3 were detected in cultured human aortic VSMC; however, only Notch2 and Notch3 intracellular domains (ICD) were increased by stimulation with Jag-1 as compared to Fc (Fig. 1B). Notch2 activation following Jag-1 stimulation was further verified by immunostaining (Fig. 1C). Prior to ligand treatment, Notch2 was localized to the cell membrane (arrowheads), but was predominantly nuclear after Jag-1 stimulation. These experiments confirm accumulation of Notch2 in VSMC following vascular injury and its expression and activation in cultured human aortic VSMC.

Jag-1 selective activation of Notch2 is required to inhibit VSMC proliferation

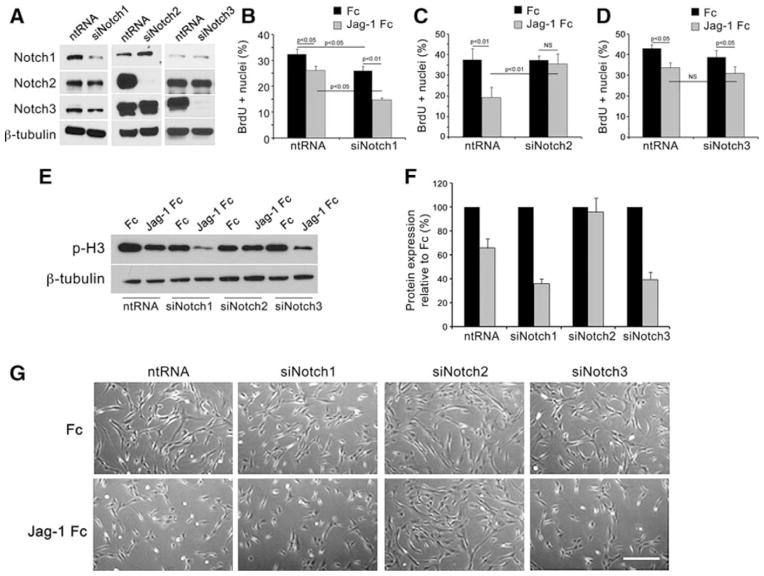

Proliferation of VSMC contributes to neointimal hyperplasia during pathological remodeling, and anti-proliferative agents have proven efficacious in reducing restenosis15. We previously reported that Jag-1 activation of Notch receptors in VSMC significantly reduced cell proliferation in addition to inducing differentiation12. To identify the receptor mediating the cell proliferation effect, we silenced Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 in VSMC using small-interfering (si) RNA. Confirmation of Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 knockdown was performed by immunoblot analysis for ICD compared to non-targeting RNA (ntRNA) control (Fig. 2A). We found each siRNA to specifically and effectively reduce its Notch target. We then analyzed Notch target gene Hes1 by quantitative reverse transcription (qRT) PCR following Jag-1 stimulation to validate suppression of Notch signaling (Online Fig. I, A–C). Knockdown of each Notch receptor significantly reduced the level of Hes1 transcript induced by Jag-1 stimulation. Finally, we assessed the effect of Notch knockdown on the VSMC differentiated phenotype. Jag-1-induced SM-actin transcripts were significantly reduced with knockdown of Notch1, Notch2, or Notch3 (Online Fig. ID). Additionally, reduction in basal levels of Notch2 and Notch3 was sufficient to reduce the ability of cells to contract a collagen gel (Online Fig. IE).

Figure 2. Jag-1 selective activation of Notch2 is required to inhibit VSMC proliferation.

A) Human aortic VSMC were transfected with 200pmol of non-targeting RNA (ntRNA), or siNotch, siNotch2, or siNotch3 and whole cell lysates collected 48h later for immunoblot analysis of each Notch ICD to validate specificity and efficiency of knockdown. VSMC with selective Notch receptor knockdown were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 42h, then pulsed with 10μM BrdU for 6h. Cells were processed for immunostaining to detect and quantify the percentage of BrdU positive nuclei in Notch1 (B), Notch2 (C) or Notch3 (D) knockdown cells. Graphed are means ± SD. E–F) VSMC transfected with ntRNA, siNotch1, siNotch2 or siNotch3 probes were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc and whole cell lysates collected after 48h for immunoblot to detect phospho-histone H3 (p-H3). Quantification of p-H3 protein relative to β-tubulin is shown (F). G) Representative phase micrographs of these VSMC are shown after stimulation with either Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h. Scale bar=200μm.

VSMC transfected with ntRNA or siRNA probes against Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 were activated with Jag-1 Fc for 48 hours and analyzed for cell proliferation. Cells were pulsed in the last 6h on ligand with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) to label cells undergoing DNA synthesis. As previously reported, Jag-1 Fc decreased cell proliferation (Fig. 2B–D). While inhibition of Notch1 (Fig. 2B) and Notch3 (Fig. 2D) did not change this, knockdown of Notch2 inhibited this suppression as compared to Fc control (Fig. 2C). We also assessed levels of phosphorylated histone H3 on serine 10 (p-H3), a marker of mitotic cells16, in Notch knockdown VSMC activated with Jag-1 Fc. Consistent with BrdU experiments, p-H3 levels were reduced by Jag-1 in control, Notch1 and Notch3 knockdown cells as compared to Fc, however no change was observed in Notch2 knockdown cells (Fig. 2E–F). The suppression in cell proliferation correlated with cell number. Cells transfected with ntRNA, siNotch1, or siNotch3 had significantly reduced cell number, whereas transfected siNotch2 populations had high cell density (Fig. 2G). These data show that Jag-1 signals exclusively through Notch2 to inhibit VSMC proliferation in vitro.

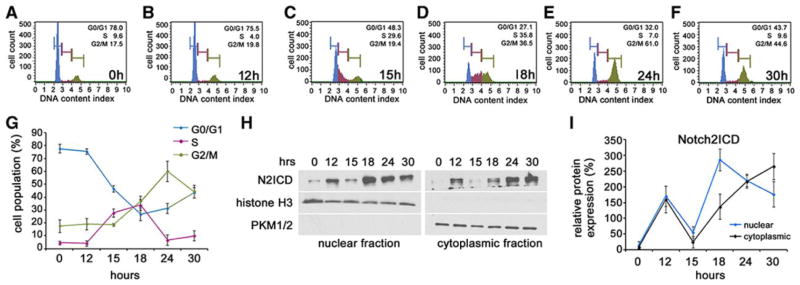

Nuclear Notch2 ICD is down regulated during entry into S-phase

Because Jag-1-specific activation of Notch2 is required to inhibit VSMC proliferation, we analyzed whether endogenous Notch2ICD expression varies during cell cycle progression. We utilized propidium iodide (PI) staining of total DNA content and analyzed the cells to quantify proportions in different phases of the cell cycle. To validate our system, VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h and the cell cycle analyzed using PI staining (Online Fig. IIA). Quantification of cells activated by Jag-1 Fc as compared to Fc revealed ~14% increase the G0/G1 population, while the S-phase and G2/M populations were reduced by ~5% and ~7%, respectively (Online Fig. IIB). To study Notch2ICD expression throughout cell cycle progression, VSMC were serum starved for 30h to synchronize the cells in G017 and then released using freshly prepared SmGM medium. Cells were harvested at 0h (30h starvation time point), 12h, 15h, 18h, 24h and 30h after releasing and simultaneously processed for cell cycle analysis (Fig. 3A–G) or nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation for Notch2ICD levels (Fig. 3H–I). Nuclear and cytoplasmic levels of Notch2ICD were at their lowest from 12h to 15h after release, concomitant with entry of the G0/G1 population into S-phase (Fig. 3G). At 18h after release, the S-phase population began moving into G2/M and simultaneous up regulation of nuclear Notch2ICD was observed (Fig. 3I, blue line). Following increased nuclear Notch2ICD expression at 18h, the population of cells in S-phase rapidly and steadily declined until 24h. Nuclear Notch2 steadily decreased through 30h as the cells normalized their proliferation rates. Steadily decreasing Notch2ICD coincided with a steady increase in Notch2ICD in the cytoplasm, suggesting nuclear export of the protein after transition of the population from S-phase to G2/M at 18h. Thus, nuclear Notch2ICD in VSMC changes during progression through the cell cycle, is lowest during entry into S-phase, and peaks during exit from S-phase.

Figure 3. Nuclear Notch2ICD is down regulated during entry into S-phase.

VSMC at passage 5 were synchronized in serum free media (SmBM) for 30h to induce G0. Freshly prepared smooth muscle growth media was added and the cells were harvested for cell cycle analysis at 0h (A), 12h (B), 15h (C), 18h (D), 24h (E) and 30h (F). G) Graphical representation of the percentage of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M at each time point analyzed. Graphed are means ± SD. H) VSMC were harvested at the same time points after release from starvation and fractionated into their nuclear (left) and cytoplasmic (right) constituents for immunoblot analysis of N2ICD. Total histone H3 and pyruvate kinase PKM 1/2 were used as loading controls for nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, respectively. Notch2ICD was normalized to loading control and quantified for each time point (I). Graphed are means ± SD.

Selective regulation of p27kip1 by Jag-1/Notch2 signaling inhibits VSMC proliferation

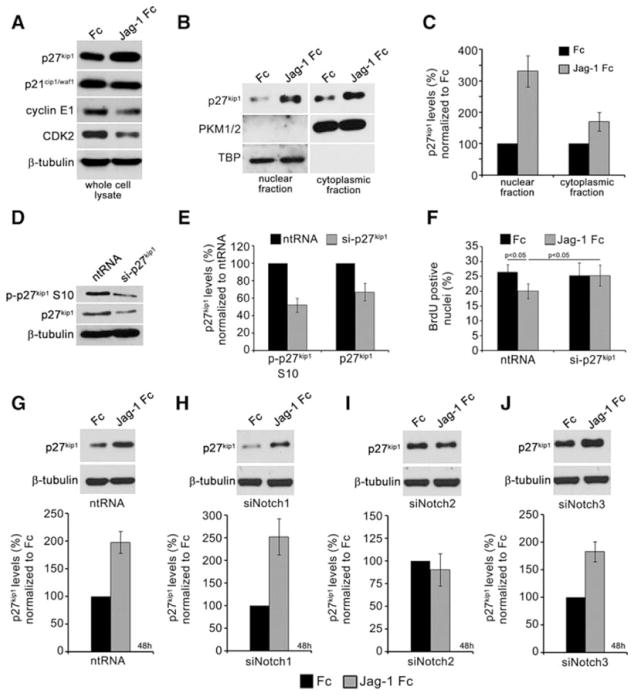

To identify cell cycle regulatory proteins targeted by Jag-1 via Notch2, we analyzed p27kip1, p21cip1/waf1, cyclin E1 and its associated cyclin dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), all important regulators of VSMC cell cycle18,19. Although p21cip1/waf1 was slightly down regulated by activation with Jag-1 Fc for 48h, p27kip1 levels doubled (Fig. 4A). Additionally, Jag-1 Fc activation inhibited expression of CDK2 and cyclin E1. One function of p27kip1 is to bind cyclin E1/CDK2 complexes and prevent cell cycle progression20. To determine if Jag-1 Fc promotes increased nuclear levels of p27kip1, we stimulated VSMC with Jag-1 Fc or Fc for 48h before fractionating the cells into nuclear and cytoplasmic components. Immunoblot analysis to detect p27kip1 protein showed increases in both nuclear and cytoplasmic levels in response to Jag-1 Fc (Fig. 4B–C), suggesting that enhanced nuclear p27kip1 expression may mediate the cell cycle inhibitory effects.

Figure 4. Selective regulation of p27kip1 by Jag-1/Notch2 signaling inhibits VSMC proliferation.

A) VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h, and cell lysates collected for immunoblot to detect total p27kip1, p21cip1/waf1, cyclin E1 and CDK2. B) Cell lysates were also fractionated into a nuclear and cytoplasmic pool, and immunoblotted to detect total p27kip1. Pyruvate kinase (PKM1/2) and TATA box binding protein (TBP) were used as cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively. C) Quantification of nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of p27kip1 in response to activation by Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h. D) VSMC were transfected with 125pmol of siRNA targeting p27kip1 (si-p27kip1) and efficiency was analyzed by immunoblot (D–E). F) VSMC transfected with ntRNA or si-p27kip1 were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 42h before pulsing with 10μM BrdU for 6h and quantifying the percentage of BrdU-positive nuclei. G–J) Immunoblot analysis and quantification of p27kip1 levels after 48h activation by Fc or Jag-1 Fc in control, Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 knockdown cells, respectively. Graphed are means ± SD.

To determine if p27kip1 is required for Jag-1 to suppress VSMC proliferation, we used an siRNA targeting p27kip1 (si-p27kip1) to suppress the induction by Jag-1 signaling. Quantification of knockdown efficiency showed that 125pmol of si-p27kip1 reduced levels of total p27kip1 and p-p27kip1 S10 by approximately 38% and 45%, respectively (Fig. 4D–E). Phosphorylation of p27kip1 on S10 is known to promote its stability and considerably increase its half-life21. Using this system, we seeded ntRNA and si-p27kip1 transfected VSMC on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 42h before pulsing with BrdU for 6h. Quantification of BrdU positive nuclei showed a significant reduction in proliferation in ntRNA receiving cells plated on Jag-1 Fc at 48h as compared to Fc (Fig. 4F), while even a moderate reduction in p27kip1 protein rescued the Jag-1-induced suppression of proliferation. These results were confirmed using PI staining in conjunction with cell cycle analysis (data not shown). These data show that the increase in p27kip1 is required for Jag-1 to suppress VSMC proliferation.

Because Notch2 selectively mediates Jag-1 signaling to reduce cell proliferation, we tested whether regulation of p27kip1 is also specific to Notch2. VSMC were transfected with ntRNA, siNotch1, siNotch2 or siNotch3, and plated on Jag-1 Fc for 48h before harvesting to analyze p27kip1 protein. We found that Jag-1 Fc upregulated expression of p27kip1 in control Notch1 and Notch3 knockdown cells but not in cells lacking Notch2 (Fig. 4G–J). These data indicate that Jag-1 induces p27kip1 expression exclusively through Notch2 to promote cell cycle arrest.

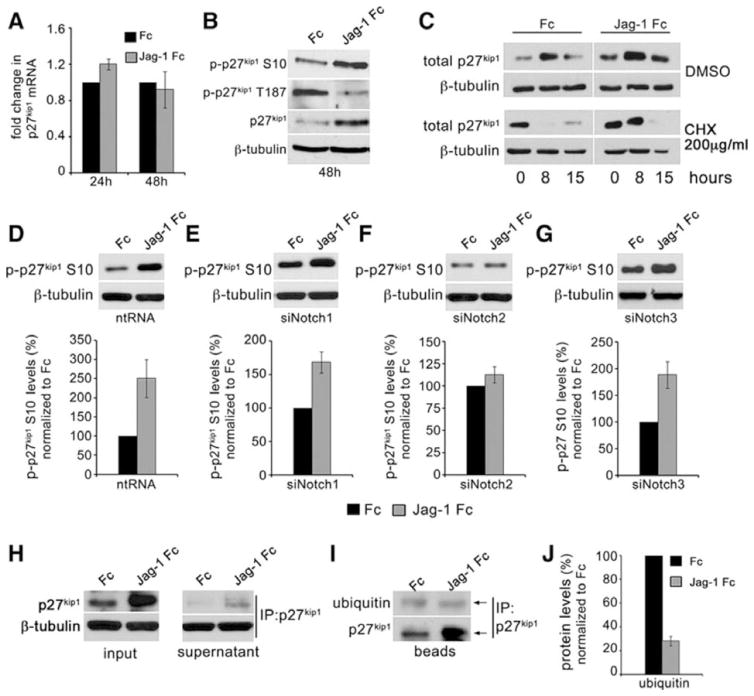

Jag-1 signaling via Notch2 stabilizes p27kip1 protein in VSMC

Canonical Notch signaling involves cleavage and translocation of NotchICD to the nucleus where it alleviates repression of the transcriptional regulator C promoter binding factor-1 (CBF-1) to promote transcriptional activation. We evaluated the levels of p27kip1 transcript after 24h and 48h activation by Jag-1 in VSMC. Using qRT-PCR, we did not observe any significant changes in p27kip1 mRNA levels following Jag-1 stimulation (Fig. 5A). Another common level of p27kip1regulation is post-translational, including phosphorylation events at specific residues that affect protein stability. S10 phosphorylated p27kip1 is the primary form in G0/G1 cells, representing ~70% of the phosphorylated protein21. Importantly, S10 phosphorylation increases the stability of p27kip1 in vivo22. In addition, p27kip1 can be phosphorylated on threonine (T)187, which promotes its turnover23. To determine if Jag-1 signaling affects levels of these phosphorylated forms, we plated VSMC on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h and analyzed whole cell lysates for total and phosphorylated forms of p27kip1. Jag-1 activation resulted in increased p-p27kip1 S10, a decrease in p-p27kip1 T187, and as anticipated, increased total p27kip1 at 48h (Fig. 5B). A profile of decreased phosphorylation on T187 and increased phosphorylation on S10 is expected to increase the stability of the protein. To determine if the overall increase in p27kip1 was indeed a result of protein stabilization, we measured its half-life. VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 24h before adding 200μM final concentration cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit de novo protein synthesis or vehicle (DMSO). Lysates were collected at 0, 8 or 15h to quantify p27kip1. Representative immunoblots (Fig. 5C) indicated that the normal half-life of p27kip1 was within 8h. However, following Jag-1 Fc stimulation, the protein level was unchanged at 8h, and had an extended half-life, decreasing only by 15h. These data demonstrate Jag-1 activation of Notch2 likely results in stabilization of the existing pool of p27kip1.

Figure 5. Jag-1 signaling via Notch2 stabilizes p27kip1 in VSMC.

A) VSMC were stimulated with Jag-1 Fc or Fc for 24h or 48h, and RNA collected for qRT-PCR analysis of p27kip1 transcript. Graphed are the fold changes relative to Fc. B) Lysates were collected from VSMC stimulated with Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h and analyzed by immunoblot for phosphorylated and total p27kip1. C) VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 24h prior to addition of DMSO or cycloheximide (CHX). Lysates were collected at indicated times. D–G) Control, Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 knockdown cells were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h and lysates collected for immunoblot analysis of p-p27kip1 S10 (top) and respective quantification relative to β-tubulin (bottom). H) VSMC were stimulated with Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h, and cell lysates immunoprecipitated (IP) to pull down total p27kip1. Analysis of whole cell lysates and remaining supernatant after p27kip1 IP confirms robust up regulation of p27kip1 by Jag-1 Fc at 48h and subsequent depletion of p27kip1 after IP (H, input and supernatant, respectively). I) Immunoprecipitated p27kip1 was analyzed by immunoblot for ubiquitin, and levels normalized to immunoprecipitated p27kip1 for quantification (J). Graphed are means ± SD.

We then tested if increased levels of p-p27kip1 S10 stimulated by Jag-1 Fc was mediated via Notch2 signaling. Similar to total p27kip1 expression (Fig. 4G–J) Jag-1 requires Notch2 to increase p-p27kip1 S10 protein. Suppression of Notch1 or Notch3 did not affect the ability of Jag-1 Fc to increase p-p27kip1 S10 (Fig. 5D–G). Ubiquitination of p27kip1 marks the protein for turnover24. Due to enhanced phosphorylation on S10 and prolonged half-life in response to Jag-1 Fc, we analyzed ubiquitination of p27kip1. VSMC were activated with Jag-1 Fc or Fc for 48h before immunoprecipitation (IP) of p27kip1. Prior to and after IP, a small amount of whole cell lysate from Fc and Jag-1 Fc conditions was analyzed by immunoblot for p27kip1 (Fig. 5H, input and supernatant, respectively). While significantly more p27kip1 was immunoprecipitated from Jag-1 activated cells as compared to Fc, relatively equal levels of ubiquitin were detected (Fig. 5I). Normalization of ubiquitin to immunoprecipitated p27kip1 suggested a ~70% reduction in ubiquitinated p27kip1 in response to activation by Jag-1 Fc (Fig. 5J), further explaining the increased half-life of p27kip1 observed in Fig. 5C. These experiments suggest that Jag-1/Notch2 signaling does not regulate p27kip1 by inducing de-novo transcription, but instead, stabilizes the existing species by promoting extensive post-transcriptional modifications. Increased S10 phosphorylation, and decreased ubiquitination likely account for enhanced p27kip1 stability and VSMC cell cycle arrest.

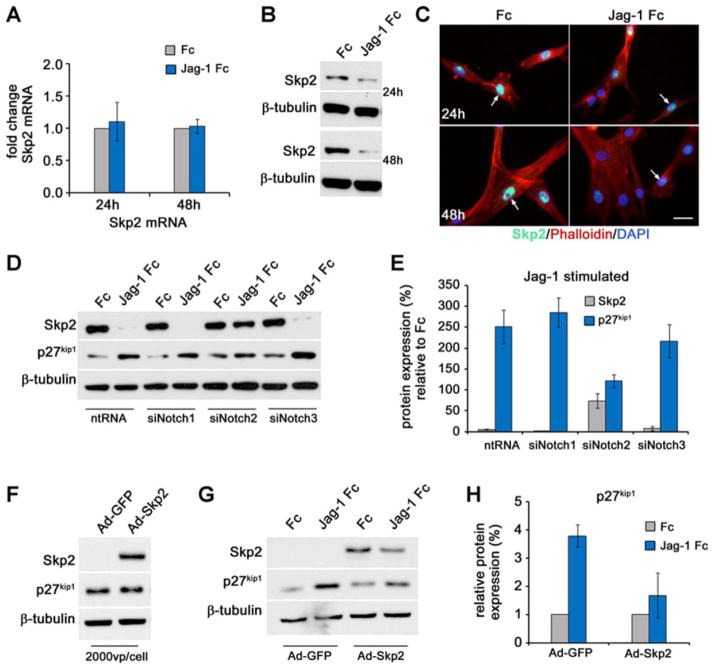

Jag-1/Notch2 regulation of p27kip1 is via down regulation of Skp2

Skp2 is a potent regulator of p27kip1 levels via ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation23. Notch signaling regulates Skp2 expression in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines25 and cell cycle progression via Skp2-dependent regulation of p27kip1 in adult stem cells26. Additionally, Skp2-mediated ubiquitination of p27kip1 regulates VSMC proliferation in culture and in response to vascular injury27, 28. In light of reduced p27kip1 ubiquitination (Fig 5I–J), and the regulation of p27kip1 by Skp2 in VSMC, we investigated whether Jag-1/Notch2 signaling regulates Skp2. VSMC were stimulated with Jag-1 Fc for 24h and 48h and Skp2 mRNA and protein levels analyzed. Although no change in Skp2 transcript was apparent at either time (Fig. 6A), Skp2 protein was robustly suppressed (Fig. 6B). In Fc stimulated cells, Skp2 expression was mainly nuclear and although Jag-1 did not affect the localization of Skp2, it significantly reduced its levels after 24h and 48h (Fig. 6C, arrowheads). Reduced Skp2 expression in the nucleus is consistent with increased nuclear p27kip1 (Fig. 4B–C).

Figure 6. Jag-1/Notch2 regulation of p27kip1 is via down regulation of Skp2.

VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 24h and 48h and harvested for qRT-PCR (A) and immunoblot analysis for Skp2 (B). Graphed are the fold changes relative to Fc. C) To study localization of Skp2, VSMC were treated as in (B) and processed for immunofluorescence analysis of Skp2 (green). F-actin and nuclei are stained in red and blue, respectively. Scale bar=25μm. D) VSMC were transfected with ntRNA, or siRNA targeting Notch1, Notch2, or Notch3, and plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h. Cell lysates were collected for immunoblot of p27kip1 and Skp2. E) Protein levels from (D) were quantified relative to Fc. F–H) VSMC were transduced with ~2000vp/cell human adenovirus encoding Skp2. After 48h, whole cell lysates were harvested for analysis of Skp2 and p27kip1 (F). Skp2 antibody was used to confirm over expression. G) VSMC were transduced as in (F), stimulated for 48h with Fc or Jag-1 Fc and analyzed by immunoblot for p27kip1. H) Quantification of p27kip1 relative to Fc from immunoblot in (G). Graphed are means ± SD.

To determine if Jag-1 regulates Skp2 expression via Notch2 exclusively, we plated control, Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 knockdown cells on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h and analyzed expression of Skp2 and p27kip1 by immunoblot (Fig. 6D–E). Knockdown of Notch2 rescued suppression of Skp2 by Jag-1 observed in control, Notch1 and Notch3 knockdown cells. In addition, decreased Skp2 by Jag-1 was associated with increased p27kip1 under all conditions except when Notch2 receptors were silenced.

VSMC response to stimuli varies depending on the source from which they are derived and can even vary within the same artery due to differential origins during development29. To determine if Jag-1 regulation of Skp2 and p27kip1 is a common pathway in VSMC derived from other vascular beds, primary human pulmonary artery or coronary artery VSMC were plated on Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h and assessed for levels of p27kip1, p-p27kip1 S10 and Skp2 (Online Fig. III). Consistent with human aorta-derived VSMC, VSMC from these sources responded to Jag-1 with increased total p27kip1, p-p27kip1 S10 and decreased Skp2 protein compared to Fc. Thus Jag-1 regulation of Skp2 and p27kip1 may be a common pathway in human VSMC from multiple origins. We also tested the effect of over expression of a constitutively active Notch1ICD, Notch2ICD or Notch3ICD on Skp2, p27kip1 and proliferation. Unlike the receptor-specific functions observed by endogenous activation of Notch by Jag-1, over expression of V5-tagged constitutively active forms of Notch1, Notch2 or Notch3 caused increased p27kip1, decreased Skp2 and decreased proliferation as indicated by Ki67 staining (Online Fig. IV, A–B). These findings show that expression of high levels of constitutively active Notch can mask receptor-specific functions compared to ligand stimulation at a more physiologically relevant level. Notch signaling is also activated by the Dll ligands, and we tested the activity of Dll1 in p27kip1 regulation. VSMC were plated on Dll-1 Fc for 48h and analyzed by immunoblot. No discernible changes were observed in p27kip1in response to Dll-1 (Online Fig. IV, C), suggesting that regulation is specific to Jag-1.

As a final evaluation, we asked whether Skp2 over expression could hinder the induction of p27kip1 in Jag-1 activated VSMC. A Skp2 adenoviral (Ad) expression construct30 was titrated in order to maintain expression while minimizing potential off-target effects (data not shown). A titer of ~2000vp/cell resulted in robust expression of Skp2 as compared to GFP control, but had minimal effect on endogenous p27kip1 levels (Fig. 6F). The absence of endogenous Skp2 in the Ad-GFP samples is due the short exposure time required to resolve a band in the Ad-Skp2 expressing cells (<5 seconds). Endogenous Skp2 was detected in Ad-GFP transduced cells with longer exposure times (~30s), however this resulted in over exposure of the Ad-Skp2 lane (data not shown). Using this approach, VSMC were transduced with Ad-GFP or Ad-Skp2 (~2000vp/cell), and given 24h recovery prior to stimulation with Fc or Jag-1 Fc for 48h. Immunoblot analysis of p27kip1 showed ~4 fold induction by Jag-1 Fc in the Ad-GFP transduced cells that could be suppressed by using the expression construct to maintain Skp2 levels in the presence of Jag-1 stimulation (Fig. 6G–H). This effect was also observed using 4000vp/cell (data not shown). Interestingly, Jag-1 stimulated Ad-Skp2 transduced cells still showed down regulation of Skp2 as compared to Fc, exemplifying the potent inhibitory action of Jag-1 on Skp2 levels. Thus, Jag-1 inhibits Skp2 levels in VSMC via activation of Notch2 exclusively, and suppression of Skp2 is required for Notch2-specific regulation of p27kip1.

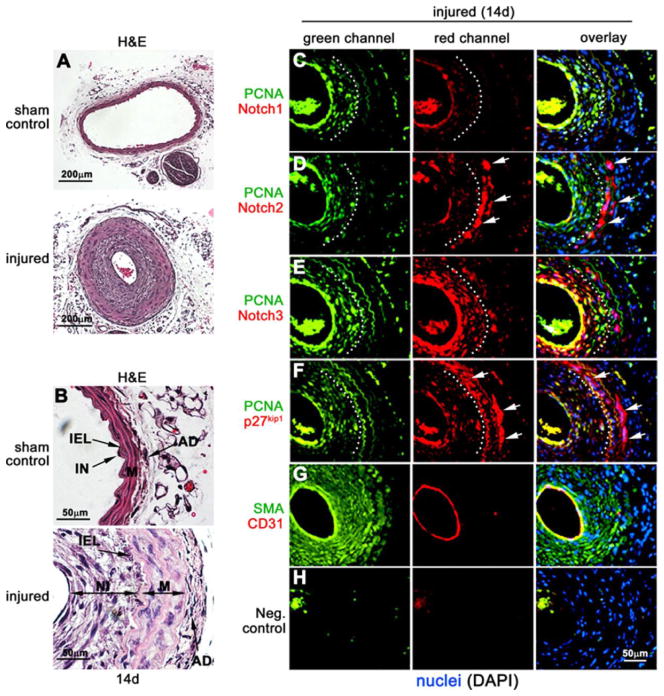

Notch2 and p27kip1 co-localize to the non-proliferative zone of injured carotid arteries

Notch signaling is involved in regulating neointimal lesion formation in response to vascular injury13, 31. Although Notch2 is required for VSMC differentiation and maturation during development7, 8, its function in vascular injury is poorly understood. Due to our observations that Notch2 increases in response to vascular injury, and inhibits VSMC proliferation via regulation of p27kip1, we studied the expression and co-localization of Notch receptors and p27kip1 in injured and normal arteries. Wild type, 8-week old male FVB mice were subjected to complete ligation of the left common carotid artery directly adjacent to the bifurcation or a sham surgery. After 14 days, carotid arteries were harvested for immunohistochemistry analysis. Histological staining revealed extensive vascular remodeling characterized by neointima formation and reduced lumen size in the ligated artery compared to sham surgery (Fig. 7A). At higher magnification, the sub-endothelial neointima appears ~8–12 layers thick and the medial layer is hypertrophic (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Notch2 and p27kip1 co-localize to the non-proliferative zone of injured carotid arteries.

Eight week old male FVB mice underwent complete ligation of the left common carotid artery (injury) or sham control surgery. Carotid arteries were harvested after 14d, embedded in paraffin and sectioned for H&E analysis (A). B) Higher magnification of control and injured arteries to visualize internal elastic lamina (IEL), intima (IN), neointima (NI), media (M) and adventitia (AD). Injured artery sections were processed immunofluorescence analysis of PCNA/Notch1 (C), PCNA/Notch2 (D), PCNA/Notch3 (E), PCNA/p27kip1 (F), SMA/CD31 (G) or antibody control (H) and counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei. Green and red channels indicated to visualize individual protein stains, and were overlaid with DAPI to show co-localization in the artery. Dotted line separates regions of high and low PCNA staining, white arrows indicate high Notch2 and p27kip1 staining in the medial layer (n=3).

To study Notch and p27kip1 expression in the proliferative and non-proliferative regions of the remodeling artery, we utilized co-staining with proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) to label proliferating cells32. In injured arteries after 14 days, PCNA staining was predominantly localized to the neointimal VSMC (Fig 7C–F, green channel, dotted white line marks the internal elastic lamina) while no PCNA positive cells were present in the sham arteries (Online Fig. V, A–D, green channel). Additionally, Notch1, Notch2 and p27kip1 expression was undetectable in sham arteries, however prominent Notch3 levels were observed in the medial VSMC (Online Fig. V, A–D). Staining for smooth muscle marker SM-actin and endothelial marker CD31 was performed to identify vessel structure and composition and a negative control for antibody specificity was utilized (Online Fig. V, E–F). In injured arteries, Notch1 was detectable in the endothelium and trace amounts in neointimal VSMC (Fig 7C). In stark contrast to uninjured arteries, Notch2 levels were high in the medial VSMC (Fig. 7D, white arrows). Interestingly, Notch2 expression was high in the non-proliferating VSMC as indicated by staining in regions that were negative for PCNA staining (Fig. 7D, overlay) Only trace amounts of Notch2 were detectable in the endothelium and neointimal VSMC whereas Notch3 was expressed throughout the injured vascular wall (Fig. 7E). Similar to Notch2 protein, high levels of p27kip1 were localized to the medial VSMC (Fig 7F white arrows) and outside of the proliferative zone. SM-actin and CD31 staining are shown to indicate cell type(s) and vessel structure (Fig. 7G). This localization of Notch receptors is consistent with our model that Notch2 and p27kip1 are upregulated and co-localized to the non-proliferative VSMC of the vascular wall following injury. Notch2 may be one regulator of p27kip1 expression in the injured vasculature that leads to re-establishment of vascular quiescence during remodeling.

DISCUSSION

Proper Notch signaling is required for the maturation of the cardiovascular system during development, and in humans, mutations of components of the Notch pathway lead to vascular disease (reviewed in3). Quiescent VSMC in vivo express high levels of Notch3 and Jag-1, while, injury or pathology promotes expression of Notch1 and Notch2 within the VSMC13 (Fig. 1). The specific roles and signaling functions of each of the four Notch receptors is not well understood. Our study is the first to identify a Notch2-specific signaling function in human vascular cells, which when activated, is predicted to suppress smooth muscle hyperproliferation. Because of the association of impaired Notch signaling and vascular disorders, there is an appreciation for targeting the Notch pathway in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases33. The most widely used Notch antagonist is gamma secretase inhibitor, which is being tested in cancer patient clinical trials. However, the lack of specificity of this enzyme for the Notch pathway34 presents a complex challenge when targeting diseases where multiple Notch receptors are active. Previous studies suggest that inhibition of some Notch pathways, including Notch1, may be effective in decreasing neointimal lesion formation13, 31. However, our findings suggest that selectively enhancing Notch2 function under conditions of VSMC hyperproliferation may promote cell cycle exit. Current attempts are indeed geared towards more selective targeting of individual Notch receptors35. We suggest that it is critical to understand the roles of each Notch receptor in specific disease processes to successfully apply targeted therapeutic interventions.

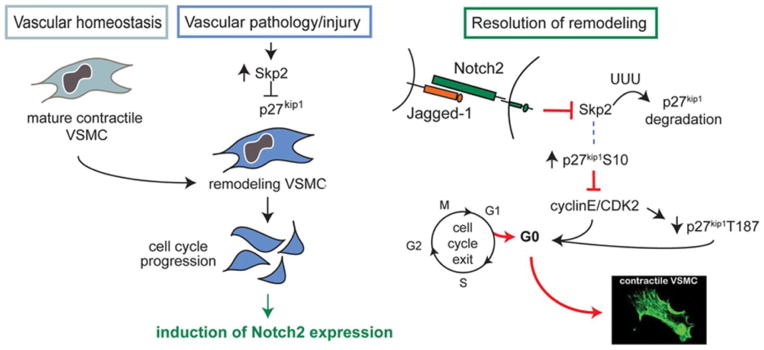

We identified a specific requirement for Notch2 in negatively regulating VSMC proliferation downstream of Jag-1. While cooperative roles can be shared between receptors, our data suggests Notch2-specific signaling roles that are unique (Fig. 8). To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify a receptor specific function for Notch2 in VSMC. Notch2 is required for Jag-1-induced VSMC differentiation via targeting of Skp2 and p27kip1 to decrease cell proliferation (Fig. 8). This cell cycle regulation is not mediated via either Notch1 or Notch3 receptors, although both of those receptors can respond to a Jag-1 signal. Thus, we hypothesize that one function of Notch2 is to provide crucial negative feedback on VSMC proliferation in response to vascular injury. Loss of differentiation of medial VSMC and subsequent migration and proliferation to the sub-endothelial compartment in response to injury has been reported36. Based on the in vitro mechanisms presented in this report, and the enhanced expression and co-localization of Notch2 and p27kip1 to medial VSMC following injury, one could speculate that Notch2 activation antagonizes excessive proliferation of medial VSMC to the neointimal layer, thereby acting to negatively regulate lesion formation and vascular occlusion.

Figure 8. Proposed model for Notch2-specific regulation of VSMC proliferation during vascular remodeling.

During vascular homeostasis, Notch2 is not present in arterial VSMC, while Notch3 is primarily expressed. Following vascular injury or the progression of disease, cytokine release and changes in the microenvironment lead to the induction of Skp2, which suppresses p27kip1. These factors contribute to loss of the contractile phenotype and VSMC proliferation. Notch2 is induced during this remodeling process in the VSMC. Unlike Notch1 and Notch3, Notch2 expression co-localized with p27kip1 to the non-proliferative medial VSMC. Our in vitro data supports a mechanism whereby Jag-1 activation of Notch2 inhibits Skp2, resulting in reduced ubiquitination and decreased turnover of p27kip1 in VSMC. As a result of increased stability, total p27kip1 and p-p27 S10 accumulate in the cell, inhibiting cyclinE/CDK2 functions. We hypothesize that reduced expression of cyclinE/CDK2 is a result of increased p27kip1 levels and accounts for dramatically decreased levels of p-p27kip1 T187. This pathway is required for Jag-1 inhibition of VSMC proliferation in vitro. Notch2 function is required for the full VSMC maturation since suppression of either Notch2 or Notch3 suppresses their differentiated, contractile phenotype.

Little is known about the contributions of Notch2 signaling during VSMC development and in response to vascular injury. Proliferation of VSMC derived from cardiac neural crest cells requires Notch2 signaling7. This result is in contrast to our model that Notch2 suppresses proliferation in VSMC from the adult injured vessel. It is possible that Notch2 proliferative signals are sensed differently in an embryonic vascular progenitor cell versus an adult differentiated VSMC. Also embryonically, a delay in VSMC differentiation is observed in developing blood vessels of Notch2 deficient mice, and these effects are severely exacerbated by dual knockout of Notch2 and Notch38. Constitutive expression of Notch2 and Notch3 are in the neointimal and medial VSMC after injury, and Notch1 expression is highest in neointimal VSMC13. While associated with many pathologies, pulmonary stenosis is often observed in patients with Allagile syndrome, caused by mutations in Jag-1 or Notch2 in humans37, and is consistent with Jag-1/Notch2 negatively regulating VSMC proliferation. Although there are many overlapping functions for Notch receptors, their differences in expression in time and space in response to vascular injury suggest the possibility of distinct receptor specific functions. The diverse origin of VSMC progenitors during development may also strongly influence the non-overlapping functions of Notch receptors in VSMC, and sensitivity to Notch2 signaling could vary during homeostasis or remodeling, and at different anatomic sites. Further identification of receptor-specific roles for Notch in large elastic arteries and smaller arterioles will be required to gain a more comprehensive picture of vascular function. Our findings are important in advancing our understanding of the molecular events contributing to arterial stenosis and other proliferative vascular disorders.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Jagged-1 activation of Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) promotes their differentiation and maturation.

The Notch pathway is re-activated in the vessel wall in response to injury and during vascular disease.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Jagged-1 activates Notch1, Notch2, and Notch3 in human VSMC; however, only Notch2 induces stabilization and nuclear accumulation of p27kip1, causing cell cycle exit.

S-phase associated kinase (Skp2) is suppressed by Jagged-1/Notch2 signaling in VSMC and is required for the induction of p27kip1.

Notch2 is induced in VSMC following vascular injury, and co-localizes with p27kip1 in non-proliferative regions of the remodeling artery.

Arterial VSMCs contribute to vascular tone and homeostasis. During vascular obstructive diseases, VSMC hyper-proliferation leads to lumen occlusion. Notch signaling regulates lesion formation after injury although specific signaling mechanisms for each of the four Notch proteins are not clear. We identied a unique function of Notch2 in VSMC, downstream of Jagged-1 stimulation. We found that Notch2 specifically suppresses proliferation via induction of the cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1, a function that cannot be mediated via Notch1 or Notch3. The mechanism includes the suppression of Skp2, a negative regulator of p27kip1. This corresponds to the stabilization and nuclear accumulation of p27kip1, leading to reduced proliferation in VSMC. During homeostasis, Notch2 is not expressed in the vessel wall, but is induced following vascular injury. Unlike widespread expression of Notch1 and Notch3 in injured VSMC, Notch2 is expressed in a sub-population of VSMC coincident with p27kip1in areas of non-proliferating VSMC. These findings support the notion that selective activation of Notch2 in VSMC suppresses proliferation and provide a potential means to reduce VSMC hyper-proliferation during vascular disease.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful for the donation of the Skp2 adenoviral expression construct generously provided by Dr. Dennis Bruemmer and colleagues at the University of Kentucky School of Medicine. We are also grateful for the resources provided by the core facilities at Maine Medical Center Research Institute in support of this project, including the Histopathology Core for tissue processing and sectioning, the Mouse Transgenic Facility for mouse surgical support, the Genomics and Bioinformatics Core for equipment for quantitative gene expression, and the Viral Vector Core for large scale purification of our adenoviral expression constructs.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants R01HL070865 and R01HL109652 (LL). The Mouse Transgenic Facility and the Viral Vector Core are supported by 5P30GM103392 (PI: R. Friesel), and the Genomics and Bioinformatics Core is supported by 8P20GM103465 (PI: D. Wojchowski). Both of these NIH COBRE awards jointly support the Histopathology Core.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CBF-1

C promoter binding factor-1

- Jag-1

Jagged-1

- NotchICD

Notch intracellular domain

- Skp2

S-phase kinase associated protein

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Alexander MR, Owens GK. Epigenetic control of smooth muscle cell differentiation and phenotypic switching in vascular development and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;74:13–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fouillade C, Monet-Lepretre M, Baron-Menguy C, Joutel A. Notch signalling in smooth muscle cells during development and disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:138–146. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher J, Gridley T, Liaw L. Molecular pathways of Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Front Physiol. 2012;3:81. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domenga V, Fardoux P, Lacombe P, Monet M, Maciazek J, Krebs LT, Klonjkowski B, Berrou E, Mericskay M, Li Z, Tournier-Lasserve E, Gridley T, Joutel A. Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2730–2735. doi: 10.1101/gad.308904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joutel A, Vahedi K, Corpechot C, Troesch A, Chabriat H, Vayssiere C, Cruaud C, Maciazek J, Weissenbach J, Bousser MG, Bach JF, Tournier-Lasserve E. Strong clustering and stereotyped nature of Notch3 mutations in CADASIL patients. Lancet. 1997;350:1511–1515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCright B, Gao X, Shen L, Lozier J, Lan Y, Maguire M, Herzlinger D, Weinmaster G, Jiang R, Gridley T. Defects in development of the kidney, heart and eye vasculature in mice homozygous for a hypomorphic Notch2 mutation. Development. 2001;128:491–502. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varadkar P, Kraman M, Despres D, Ma G, Lozier J, McCright B. Notch2 is required for the proliferation of cardiac neural crest-derived smooth muscle cells. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1144–1152. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Q, Zhao N, Kennard S, Lilly B. Notch2 and Notch3 function together to regulate vascular smooth muscle development. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X, Zou Y, Zhou Q, Huang L, Gong H, Sun A, Tateno K, Katsube KI, Radtke F, Ge J, Minamino T, Komuro I. Role of Jagged1 in arterial lesions after vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2000–2006. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Hoover JL, Simmons CA, Lindner V, Shebuski RJ. Remodeling and neointimal formation in the carotid artery of normal and P-selectin-deficient mice. Circulation. 1997;96:4333–4342. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang Y, Urs S, Boucher J, Bernaiche T, Venkatesh D, Spicer DB, Vary CP, Liaw L. Notch and transforming growth factor-beta (TGFbeta) signaling pathways cooperatively regulate vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17556–17563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boucher JM, Peterson SM, Urs S, Zhang C, Liaw L. The miR-143/145 cluster is a novel transcriptional target of Jagged-1/Notch signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28312–28321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y, Takeshita K, Liu PY, Satoh M, Oyama N, Mukai Y, Chin MT, Krebs L, Kotlikoff MI, Radtke F, Gridley T, Liao JK. Smooth muscle Notch1 mediates neointimal formation after vascular injury. Circulation. 2009;119:2686–2692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.790485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Kennard S, Lilly B. NOTCH3 expression is induced in mural cells through an autoregulatory loop that requires endothelial-expressed JAGGED1. Circ Res. 2009;104:466–475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wessely R. New drug-eluting stent concepts. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:194–203. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota T, Lipp JJ, Toh BH, Peters JM. Histone H3 serine 10 phosphorylation by Aurora B causes HP1 dissociation from heterochromatin. Nature. 2005;438:1176–1180. doi: 10.1038/nature04254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen M, Huang J, Yang X, Liu B, Zhang W, Huang L, Deng F, Ma J, Bai Y, Lu R, Huang B, Gao Q, Zhuo Y, Ge J. Serum starvation induced cell cycle synchronization facilitates human somatic cells reprogramming. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner FC, Boehm M, Akyurek LM, San H, Yang ZY, Tashiro J, Nabel GJ, Nabel EG. Differential effects of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p27(Kip1), p21(Cip1), and p16(Ink4) on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2000;101:2022–2025. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.17.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner FC, Greutert H, Barandier C, Frischknecht K, Luscher TF. Different cell cycle regulation of vascular smooth muscle in genetic hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:184–188. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000082360.65547.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lacy ER, Filippov I, Lewis WS, Otieno S, Xiao L, Weiss S, Hengst L, Kriwacki RW. p27 binds cyclin-CDK complexes through a sequential mechanism involving binding-induced protein folding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:358–364. doi: 10.1038/nsmb746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishida N, Kitagawa M, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama K. Phosphorylation at serine 10, a major phosphorylation site of p27(Kip1), increases its protein stability. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25146–25154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotake Y, Nakayama K, Ishida N, Nakayama KI. Role of serine 10 phosphorylation in p27 stabilization revealed by analysis of p27 knock-in mice harboring a serine 10 mutation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1095–1102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirane M, Harumiya Y, Ishida N, Hirai A, Miyamoto C, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama K, Kitagawa M. Down-regulation of p27(Kip1) by two mechanisms, ubiquitin-mediated degradation and proteolytic processing. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13886–13893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dohda T, Maljukova A, Liu L, Heyman M, Grander D, Brodin D, Sangfelt O, Lendahl U. Notch signaling induces SKP2 expression and promotes reduction of p27Kip1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3141–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarmento LM, Huang H, Limon A, Gordon W, Fernandes J, Tavares MJ, Miele L, Cardoso AA, Classon M, Carlesso N. Notch1 modulates timing of G1-S progression by inducing SKP2 transcription and p27 Kip1 degradation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:157–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu YJ, Sala-Newby GB, Shu KT, Yeh HI, Nakayama KI, Nakayama K, Newby AC, Bond M. S-phase kinase-associated protein-2 (Skp2) promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in vivo. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu YJ, Bond M, Sala-Newby GB, Newby AC. Altered S-phase kinase-associated protein-2 levels are a major mediator of cyclic nucleotide-induced inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2006;98:1141–1150. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000219905.16312.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majesky MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1248–1258. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gizard F, Zhao Y, Findeisen HM, Qing H, Cohn D, Heywood EB, Jones KL, Nomiyama T, Bruemmer D. Transcriptional regulation of S phase kinase-associated protein 2 by NR4A orphan nuclear receptor NOR1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35485–35493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caolo V, Schulten HM, Zhuang ZW, Murakami M, Wagenaar A, Verbruggen S, Molin DG, Post MJ. Soluble Jagged-1 inhibits neointima formation by attenuating Notch-Herp2 signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1059–1065. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.217935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan D, Yang J, Lu F, Xu D, Zhou L, Shi A, Cao K. Platelet-derived growth factor BB modulates PCNA protein synthesis partially through the transforming growth factor beta signalling pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;85:606–615. doi: 10.1139/o07-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Redmond EM, Guha S, Walls D, Cahill PA. Investigational Notch and Hedgehog inhibitors--therapies for cardiovascular disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2011;20:1649–1664. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.628658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haapasalo A, Kovacs DM. The many substrates of presenilin/gamma-secretase. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25:3–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, Hagenbeek TJ, de Leon GP, Chen Y, Finkle D, Venook R, Wu X, Ridgway J, Schahin-Reed D, Dow GJ, Shelton A, Stawicki S, Watts RJ, Zhang J, Choy R, Howard P, Kadyk L, Yan M, Zha J, Callahan CA, Hymowitz SG, Siebel CW. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464:1052–1057. doi: 10.1038/nature08878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thyberg J. Phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells during formation of neointimal thickenings following vascular injury. Histol Histopathol. 1998;13:871–891. doi: 10.14670/HH-13.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDaniell R, Warthen DM, Sanchez-Lara PA, Pai A, Krantz ID, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB. NOTCH2 mutations cause Alagille syndrome, a heterogeneous disorder of the notch signaling pathway. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:169–173. doi: 10.1086/505332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.