The actin-binding protein ADD1 associates with mitotic spindles through Myo10 and is crucial for proper spindle assembly and mitotic progression.

Abstract

Mitotic spindles are microtubule-based structures, but increasing evidence indicates that filamentous actin (F-actin) and F-actin–based motors are components of these structures. ADD1 (adducin-1) is an actin-binding protein that has been shown to play important roles in the stabilization of the membrane cortical cytoskeleton and cell–cell adhesions. In this study, we show that ADD1 associates with mitotic spindles and is crucial for proper spindle assembly and mitotic progression. Phosphorylation of ADD1 at Ser12 and Ser355 by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 enables ADD1 to bind to myosin-X (Myo10) and therefore to associate with mitotic spindles. ADD1 depletion resulted in distorted, elongated, and multipolar spindles, accompanied by aberrant chromosomal alignment. Remarkably, the mitotic defects caused by ADD1 depletion were rescued by reexpression of ADD1 but not of an ADD1 mutant defective in Myo10 binding. Together, our findings unveil a novel function for ADD1 in mitotic spindle assembly through its interaction with Myo10.

Introduction

The simple overview of cell division in animal cells is that chromosome segregation is driven by microtubule dynamics in the mitotic spindle, whereas cytokinesis is driven by actin–myosin II dynamics in the contractile furrow. However, increasing evidence indicates that coordinated interactions between the two cytoskeletal systems are necessary to ensure the proper progression of cell division. For example, actin is involved in positioning the spindle via an interaction with astral microtubules (Gundersen and Bretscher, 2003). In contrast, aster and midzone microtubules position the cleavage furrow during anaphase (D’Avino et al., 2005). Remarkably, actin and myosin have been implicated in the organization and function of the spindle under certain conditions (Silverman-Gavrila and Forer, 2000; Rosenblatt et al., 2004).

Myosin-X (Myo10) belongs to a subclass of unconventional myosins (Berg et al., 2000). Its heavy chain consists of an NH2-terminal motor domain that binds to actin filaments (F-actin) and generates force, a neck domain with three IQ motif binding sites for calmodulin-like light chain, and a long tail domain at the C terminus, which contains three pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, a myosin tail homology 4 (MyTH4) domain, and a FERM (band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin) domain (Kerber and Cheney, 2011). The cluster of three PH domains allows Myo10 to target the plasma membrane via binding to phosphatidylinositol, which contributes to Myo10 distribution to filopodia (Umeki et al., 2011). The MyTH4 domain of Myo10 is sufficient to bind to microtubules (Weber et al., 2004), and this property makes Myo10 an unusual link between the microtubule and actin cytoskeletons. Remarkably, Myo10 has been implicated in the positioning of the meiotic spindles at the cortex in unfertilized Xenopus laevis eggs (Weber et al., 2004; Woolner and Papalopulu, 2012) and in positioning the mitotic spindle parallel to the substratum in cultured cells (Toyoshima and Nishida, 2007). In addition to positioning the spindle, Myo10 is required for mitotic spindle assembly and spindle length control (Woolner et al., 2008). Nevertheless, more studies are required to understand the mechanism of Myo10 regulation of the assembly and function of mitotic spindles.

Adducin (ADD) is an actin-binding protein that is important for the stabilization of the membrane cortical cytoskeleton (Gardner and Bennett, 1987; Hughes and Bennett, 1995) and cell–cell adhesion (Abdi and Bennett, 2008; Naydenov and Ivanov, 2010). The ADD family consists of three closely related genes: ADD1, ADD2, and ADD3. ADD1 (α isoform) and ADD3 (γ isoform) are found in most tissues, whereas ADD2 (β isoform) is abundant in erythrocytes and the brain (Gardner and Bennett, 1986; Bennett et al., 1988; Dong et al., 1995). All ADD isoform proteins are similar in their domain structures, which consist of a globular NH2-terminal head domain, a neck domain, and a C-terminal tail domain (Joshi and Bennett, 1990; Joshi et al., 1991; Dong et al., 1995). The C-terminal tail domain contains a 22-residue myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate (MARCKS)–related domain that has high homology to the MARCKS protein (Joshi et al., 1991; Dong et al., 1995). The MARCKS-related domain is required for the interaction of ADD with F-actin, spectrin, and calmodulin (Joshi et al., 1991; Dong et al., 1995; Li et al., 1998). The phosphorylation of ADD by protein kinase C or protein kinase A in the MARCKS-related domain diminishes its interaction with F-actin and spectrin (Matsuoka et al., 1996, 1998). The head domain is the most conserved region in the ADD family, but its exact function remains unclear.

In this study, we surprisingly found that ADD1 associates with mitotic spindles via its head domain. This observation prompted the question of whether ADD is involved in mitotic regulation. We found that ADD1 is phosphorylated by CDK1 during mitosis, which allows ADD1 to interact with Myo10 and to associate with mitotic spindles. Our results suggest that the interaction of ADD1 with Myo10 is required for proper spindle assembly and function.

Results and discussion

Association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles through its head domain

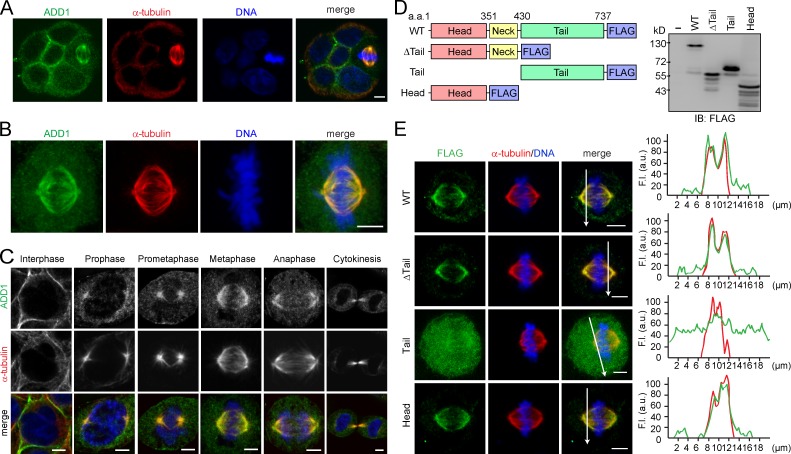

Although ADD1 mainly localized at the cell–cell junctions of MDCK epithelial cells, ADD1 apparently associated with mitotic spindles when the cells entered mitosis (Fig. 1 A). The association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles was also observed in other types of cells, such as HeLa cells (Fig. 1 B). The specificity of the ADD1 staining at mitotic spindles was verified by ADD1 knockdown (Fig. S1 A). In addition, ADD1 no longer associated with mitotic spindles upon the disruption of spindle microtubules by nocodazole (Fig. S1 B). The withdrawal of nocodazole restored the assembly of mitotic spindles and the association of ADD1 (Fig. S1 B). In contrast, the disruption of the actin cytoskeleton by latrunculin did not affect the association of ADD1 with the spindle (Fig. S1 C). As early as prophase, ADD1 was found to associate with mitotic asters before the breakdown of the nuclear envelope (Fig. 1 C). In metaphase and anaphase, ADD1 more visibly associated with spindle fibers and poles (Fig. 1 C). During cytokinesis, ADD1 retained its association with midzone microtubules (Fig. 1 C). Like endogenous ADD1, FLAG epitope–tagged ADD1 (FLAG-ADD1) associated with mitotic spindles throughout mitosis (Fig. S1, D and E).

Figure 1.

Association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles via its head domain. (A) MDCK cells were allowed to form cell colonies and were then stained for ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. Note that one of the cells in the colony is undergoing mitosis. (B) HeLa cells were stained for ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. Representative images from confocal z-stack projections are shown. (C) HeLa cells were stained for ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. Representative confocal images show the association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles throughout mitosis and with midzone microtubules during cytokinesis. (D) FLAG epitope–tagged ADD1 (FLAG-ADD1) and mutants were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells and were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-FLAG. (E) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-ADD1 and mutants were stained for FLAG-ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. (left) Representative confocal images from the cells in metaphase are shown, which were from a single experiment out of three repeats (n > 140). (right) Graphs show the relative fluorescence intensity (F.I.) at the lines that were scanned by confocal microscopy. a.u., arbitrary unit. Bars, 5 µm.

To determine which domain of ADD1 is responsible for its association with mitotic spindles, several deleted mutants of FLAG-ADD1 were constructed (Fig. 1 D). The ADD1 mutant without the tail domain retained its ability to associate with spindles, indicating that the tail domain is not required for ADD1 to localize at mitotic spindles (Fig. 1 E). Moreover, the tail domain by itself was diffusively distributed in the cytoplasm and failed to associate with mitotic spindles, whereas the head domain by itself was sufficient for the association (Fig. 1 E). These results together indicate that the head domain of ADD1 is responsible for its association with mitotic spindles.

Phosphorylation of ADD1 at S12 and S355 by CDK1 is crucial for its association with mitotic spindles

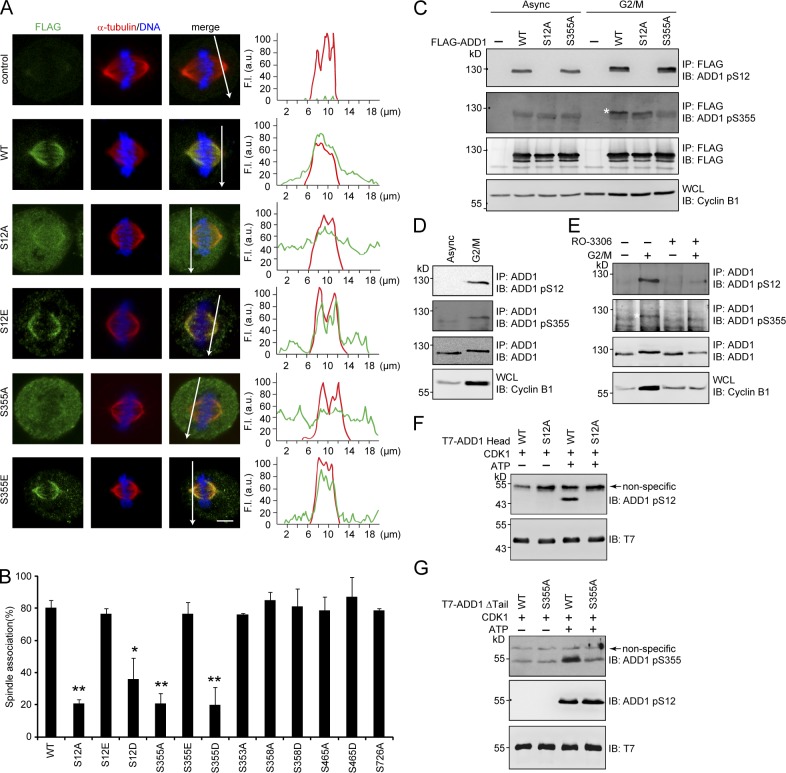

Because the molecular mass of ADD1 increased during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Fig. S2 A), we speculated that ADD1 might undergo certain posttranslational modifications in the G2/M phase. Indeed, several phosphorylation sites on ADD1 from the cells arrested in the G2/M phase were identified by mass spectrometry (MS; Fig. S2 B). Remarkably, S12A and S355A mutants became diffusively distributed in the cytoplasm of mitotic cells (Fig. 2 A), whereas S353A, S358A, S465A, and S726A mutants retained their association with mitotic spindles (Figs. 2 B and S2 C). The phosphorylation mimetic mutants S12E and S355E were able to associate with mitotic spindles (Fig. 2 A). Of note, S12D and S355D behaved like S12A and S355A (Figs. 2 B and S2 C), indicating that aspartate does not mimic phosphorylated serine in these two cases.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of ADD1 at Ser12 and Ser355 by CDK1 is crucial for ADD1 association with mitotic spindles. (A) HeLa cells transiently expressing FLAG-ADD1 and mutants were stained for FLAG-ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. (left) Representative confocal images from the cells in metaphase are shown, which were from a single experiment out of three repeats (n > 160). (right) Graphs show the relative fluorescence intensity (F.I.) of the lines that were scanned by confocal microscopy. a.u., arbitrary unit. Bar, 5 µm. (B) The percentage of FLAG-ADD1 association with mitotic spindles in the total number of mitotic cells counted was measured (n > 160). Values (means ± SD) are from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) FLAG-ADD1 and mutants were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells. The cells were synchronized in the G2/M phase or remained asynchronized (Async) before they were lysed. FLAG-ADD1 and mutants were immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-FLAG, and the immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with antibodies to ADD1 pS12 or pS355. S355-phosphorylated ADD1 is indicated by a white asterisk. WCL, whole-cell lysates. (D) HeLa cells were synchronized in the G2/M phase or remained asynchronized before they were lysed. Endogenous ADD1 was immunoprecipitated by anti-ADD1, and the immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to ADD1 pS12 or pS355. (E) HeLa cells were synchronized in the G2/M phase (+) or remained asynchronized (−). The cells were treated with 10 µM of the CDK1 inhibitor RO-3306 for 1 h before they were lysed. Endogenous ADD1 was immunoprecipitated by anti-ADD1, and the immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to ADD1 pS12 or pS355. S355-phosphorylated ADD1 is indicated by a white asterisk. (F and G) Purified T7-tagged ADD1 head domain (T7-ADD1 head) or the mutant with a deletion of the tail domain (Δtail) were incubated with recombinant CDK1 in the presence (+) or absence (−) of ATP for 30 min. The phosphorylation of ADD1 at S12 and S355 was analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies to ADD1 pS12 or pS355.

To facilitate the detection of ADD1 phosphorylation at S12 and S355, antibodies specific to phosphorylated S12 and S355 of ADD1 were generated (Fig. 2 C). The phosphorylation of ADD1 at S12 and S355 was indeed increased in the G2/M phase (Fig. 2, C and D), which was inhibited by RO-3306, a specific inhibitor for the mitotic kinase CDK1 (Fig. 2 E). In vitro, CDK1 was able to directly phosphorylate ADD1 at S12 and S355 (Fig. 2, F and G). These results together suggest that the phosphorylation of ADD1 at S12 and S355 by CDK1 may facilitate the association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles.

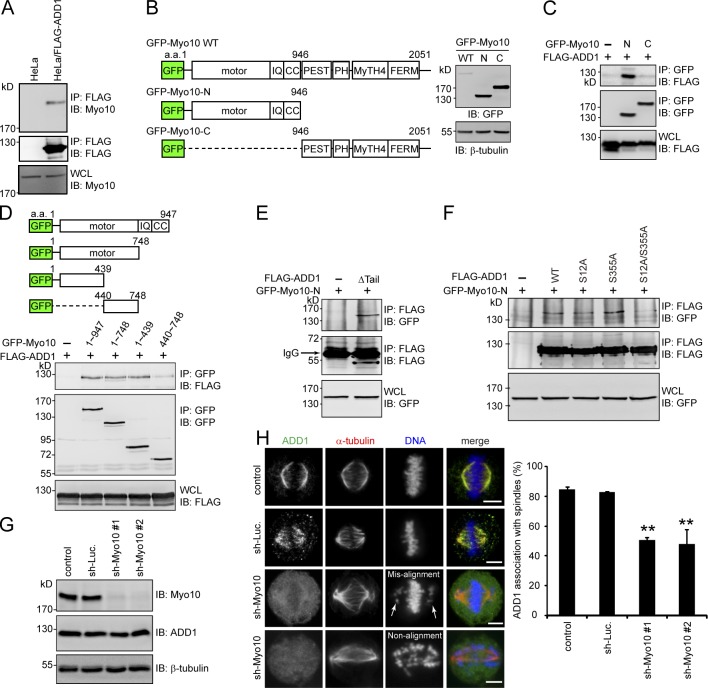

ADD1 associates with mitotic spindles through Myo10

Because purified FLAG-ADD1 does not bind to polymerized microtubules in vitro (Fig. S3), ADD1 may indirectly associate with mitotic spindles through other spindle-associated proteins. In this study, we demonstrated that FLAG-ADD1 interacts with endogenous Myo10 (Fig. 3 A). To characterize the interaction between ADD1 and Myo10, GFP-fused Myo10 and its mutants were constructed (Fig. 3 B). The NH2-terminal half of Myo10 contains a highly conserved motor domain, three IQ domains, and a coiled-coil domain. The MyTH4 domain and FERM domain in the C terminus of Myo10 are known to mediate the association of Myo10 with microtubules (Weber et al., 2004). We found that FLAG-ADD1 specifically bound to the NH2 terminus (aa 1–439) of the Myo10 motor domain (Fig. 3, C and D). In addition, we demonstrated that the head and neck domains of ADD1 mediated the interaction with Myo10 (Fig. 3 E) and that the mutation of ADD1 at S12 and S355 abrogated its capability to bind to Myo10 (Fig. 3 F). Myo10 depletion significantly (∼50%) prevented the association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles, accompanied by spindle distortion, spindle length elongation, and chromosome misalignment (Fig. 3, G and H). These data together suggest that ADD1 may associate with mitotic spindles through its interaction with Myo10.

Figure 3.

ADD1 phosphorylation at S12 and S355 is required for its interaction with the motor domain of Myo10. (A) The cell lysates prepared from HeLa cells or those stably expressing FLAG-ADD1 were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity resins. The bound proteins were eluted from the resins with FLAG peptides and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with anti-Myo10 or anti-FLAG. WCL, whole-cell lysates. (B) GFP-fused Myo10 (GFP-Myo10) and mutants were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells and were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP. The scheme shows the domain structures of GFP-Myo10. CC, coiled-coil domain; PEST, polypeptide enriched in proline, glutamic acid, serine, and threonine residues. (C and D) FLAG-ADD1 was transiently coexpressed with GFP-Myo10 or its mutants in HEK293 cells. GFP-Myo10 was immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-GFP, and the immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG or anti-GFP. (E) GFP-Myo10-N was transiently coexpressed with (+) or without (−) the FLAG-ADD1Δtail mutant in HEK293 cells. The cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG, and the immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP or anti-FLAG. (F) GFP-Myo10-N was transiently coexpressed with FLAG-ADD1 or its mutants in HEK293 cells. FLAG-ADD1 was immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG, and the immunocomplexes were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP or anti-FLAG. (G) HeLa cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs to Myo10 (sh-Myo10 #1 and sh-Myo10 #2) or to luciferase (sh-Luc.) as a control. The expression levels of Myo10, ADD1, and β-tubulin (as a loading control) were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (H) The cells, as in G, were stained for ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. Arrows indicate misaligned chromosomes. The percentage of ADD1 association with mitotic spindles in the total number of mitotic cells counted was measured (n > 270). Values (means ± SD) are from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01. Bars, 5 µm.

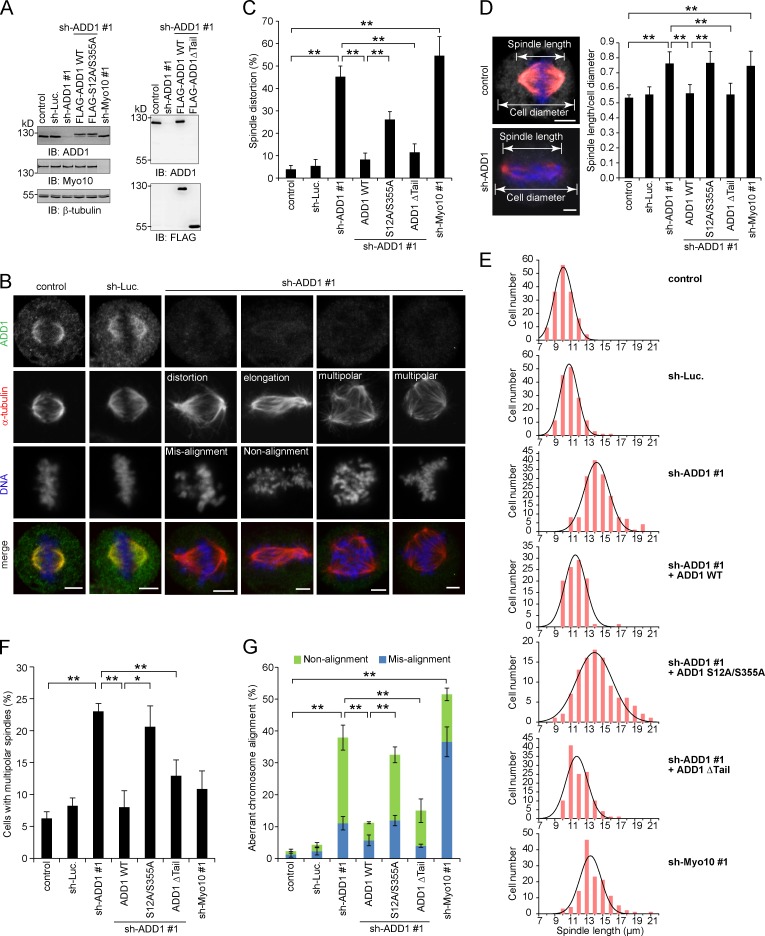

ADD1 depletion causes disorganized mitotic spindles

The effect of ADD1 depletion on mitotic spindles was analyzed (Fig. 4 A). We found that ADD1 depletion led to disorganized mitotic spindles (Fig. 4 B), which were characterized by distorted spindles (Fig. 4 C), elongated spindle length (Fig. 4, D and E), and multipolar spindles (Fig. 4 F). In addition, ADD1 depletion caused aberrant chromosome alignment, including misalignment and nonalignment (Fig. 4 G). Of note, most of the cells with distorted spindles also exhibited elongated spindle length, accompanied by chromosome nonalignment (Fig. 4 B). Importantly, the mitotic defects induced by ADD1 depletion were restored by the reexpression of FLAG-ADD1 but not by the S12A/S355A mutant (Fig. 4, C–G). Because the S12A/S355A mutant failed to interact with Myo10 (Fig. 3 D), our results together suggest that the interaction of ADD1 with Myo10 may be important for the assembly and function of mitotic spindles. Like FLAG-ADD1, the mutant lacking the tail domain (Δtail) was able to rescue the defects in ADD1-depleted cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Depletion of ADD1 results in distorted, elongated, and multipolar spindles. (A) HeLa cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs to ADD1 (shADD1 #1), Myo10 (shMyo10 #1), or luciferase (sh-Luc). FLAG-ADD1 or mutants (S12A/S355A and Δtail) were reexpressed in the cells whose endogenous ADD1 had been depleted. An equal amount of whole-cell lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. (B) The cells were stained for ADD1, α-tubulin, and DNA. (C) The percentage of distorted spindles in the total number of mitotic cells counted was measured (n > 700). (D) The cells were stained for ADD1 (gray), α-tubulin (red), and DNA (blue). The ratio of spindle length to cell diameter was measured (n > 90). (E) The spindle length of the mitotic cells was measured (n > 90). The results were obtained from three independent experiments. The best-fit Gaussian distribution is shown in the black curves. (F) The percentage of multipolar spindles in the total number of mitotic cells counted was measured (n > 700). (G) The percentage of aberrant chromosome alignment in the total number of mitotic cells counted was measured (n > 700). Values (means ± SD) are from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Bars, 5 µm.

ADD1 depletion causes aberrant congression and segregation of chromosomes in mitotic cells

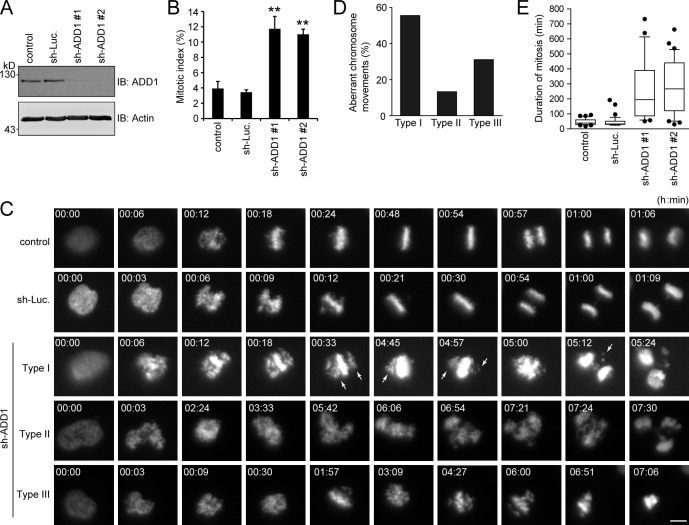

ADD1 depletion significantly increased the mitotic index in HeLa cells (Fig. 5, A and B). Next, the effect of ADD1 depletion on mitosis was monitored in living HeLa cells that stably expressed mCherry–histone H2B (Fig. 5 C). ADD1 depletion apparently caused aberrant congression and segregation of chromosomes in mitotic cells (Fig. 5 C and Videos 1–5). This aberrance can be classified into three types (Fig. 5 D). In type I, chromosomes undergo incomplete congression and then proceed to segregation, which leads to micronuclei in daughter cells (Video 3). In type II, chromosomes proceed to segregation without congression, which often leads to multiple nuclei in daughter cells (Video 4). In type III, chromosomes undergo several rounds of incomplete congression but do not proceed to segregation, which eventually leads to cell apoptosis (Video 5). The aberrance in chromosomal congression/segregation by ADD1 depletion led to prolonged mitosis (Fig. 5 E).

Figure 5.

ADD1 depletion causes aberrant congression and segregation of chromosomes. (A) HeLa cells expressing mCherry–histone H2B were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNAs to ADD1 (sh-ADD1 #1 and #2) or luciferase (sh-Luc). The expression level of ADD1 or actin (as a loading control) was analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. (B) The cells were stained for DNA, and the percentage of mitotic cells in the total number of cells was measured (n > 2,044). Values (means ± SD) are from three independent experiments. **, P < 0.01. (C) Images of HeLa cells expressing mCherry–histone H2B were acquired by time-lapse epifluorescent microscopy (Axio Observer.D1). Frames were taken every 3 min for 24 h. Arrows indicate misaligned chromosomes. Bar, 5 µm. (D) The defect in chromosome movement caused by ADD1 depletion was classified into three types (see the seventh paragraph in Results and discussion for details). The percentage of each type of defect in the total chromosomal aberrance was measured (n > 25). (E) The duration from chromosome condensation to anaphase onset was measured (n > 25). The results are expressed as box and whisker plots. The horizontal line in each box is the median. The boxes represent 50% of all measurements from the 25th to 75th percentile, and whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles. Values (means ± SD) are from three independent experiments.

ADD1 is well known for its function in the stabilization of the membrane cortical cytoskeleton and cell–cell junctions, which relies on its interaction with F-actin and spectrin (Hughes and Bennett, 1995; Abdi and Bennett, 2008). ADD1 binds to F-actin via its tail domain (Mische et al., 1987; Kuhlman et al., 1996; Li et al., 1998); however, we show here that the head domain of ADD1 is responsible for its association with mitotic spindles and its interaction with Myo10. This observation indicates that the function of ADD1 is not always dependent on F-actin and reveals a novel function of ADD1 through its head domain. In addition, we demonstrate that the phosphorylation of ADD1 at Ser12 (in the head domain) and Ser355 (in the neck domain) by CDK1 is essential for the interaction of ADD1 with Myo10, suggesting that the phosphorylation of ADD1 by CDK1 may induce conformational changes, leading to the exposure of the head domain to Myo10. Therefore, we propose a possible scenario in which ADD1 is first phosphorylated at the C-terminal MARCKS-related domain by a kinase that is activated in the G2/M phase, which diminishes the interactions of ADD1 with F-actin, and is subsequently phosphorylated by CDK1, which leads to ADD1’s interaction with Myo10 and its association with mitotic spindles.

The myosin motor domain has relatively few known interacting proteins other than F-actin. For example, the unusually large loop 2 region in the motor domain of myosin-IX is reported to bind to calmodulin (Liao et al., 2010), and the myosin chaperone UNC-45 is likely to bind to the myosin motor domain (Gazda et al., 2013). In this study, we show that ADD1 binds to the motor domain of Myo10. This finding affords the possibility that the motor activity of Myo10 may be modulated by ADD1 binding. It has been shown that the binding of the lissencephaly protein Lis1 to the motor domain of dynein (a microtubule-based motor protein) affects the dynein mechanical behavior, leading to a prolonged interaction of dynein with microtubules and thereby to slower microtubule sliding (McKenney et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012).

The role of Myo10 in spindle positioning and spindle length control is F-actin dependent (Woolner et al., 2008), which supports the spindle F-actin idea. In fact, F-actin cables can actually be seen to surround mitotic spindles in early Xenopus embryo mitosis (Woolner et al., 2008). In addition, the spindle F-actin structures have been shown to be more dynamic than regular F-actin structures (Velarde et al., 2007; Mitsushima et al., 2010; Field et al., 2011). The Arp2/3 protein complexes that tend to nucleate branched networks of short actin filaments were found to be involved in the formation of the spindle F-actin (Mitsushima et al., 2010; Field et al., 2011), suggesting that the spindle F-actin might be branched, short F-actin structures. Myo10 was initially identified as a motor protein localized to the filopodia (Berg et al., 2000), which are a type of membrane protrusion that contains a core of parallel F-actin. These studies together suggest that Myo10 may bind to parallel and branched F-actin under different circumstances. It is not known whether this property of Myo10 is affected by ADD1 binding. In summary, this work not only unveils a novel role for ADD1 in the spindle assembly but also highlights the significance of ADD1–Myo10 interactions in mitosis.

Materials and methods

Materials

The rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific to ADD1 pS12 and pS355 were generated using synthesized peptides C-SRAAVVTpSP and C-KSRpSPGSPVGE, respectively, as antigens (GeneTex, Inc.). The rabbit anti-ADD1 (H-100), mouse anti–β-tubulin (D-10), mouse anti–cyclin B1, and mouse anti-Myo10 (C-1) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The mouse anti-FLAG (M2), rabbit anti-FLAG, mouse anti–α-tubulin (DM1A), mouse anti-GFP (B-2), mouse anti–β-actin antibodies, and nocodazole were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The mouse anti-T7 antibody was purchased from EMD Millipore. The mouse anti-GFP antibody and X-tremeGENE HP were purchased from Roche. The HRP-conjugated goat anti–rabbit or goat anti–mouse antibodies and rabbit anti–mouse IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. Alexa Fluor 488– and Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated secondary antibodies and Lipofectamine were purchased from Invitrogen. The CDK1 inhibitor RO-3306 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences. Purified CDK1/cyclin B1 was purchased from EMD Millipore.

Plasmids and mutagenesis

For FLAG-ADD1, the human ADD1 cDNA from pEGFP-C1-ADD (Chen et al., 2007) was cloned into pCMV-3Tag-3A vector (Agilent Technologies) by SacI and BamHI sites. For deleted mutants of FLAG-ADD1, the corresponding cDNA fragments were amplified by PCR using pCMV-3Tag-3A-ADD1 as the template with the following primers and were subcloned into pCMV-3Tag-3A vector. For the Δtail mutant (aa 1–430), the forward primer was 5′-CGGGATCCCGATGAATGGTGATTCTCGTGCTGCG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GAATTCGCAAGTGCCCGAATCACCGTCACT-3′. For the head domain (aa 1–350), the forward primer was 5′-CGGGATCCCGATGAATGGTGATTCTCGTGCTGCG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GGAATTCTTTGTACTTCTCAGGATTCAGCAGGAC-3′. For the tail domain (aa 431–737), the forward primer was 5′-CGGGATCCATGTGCTCCCCACTCAGACACAGTTTT-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-GGAGAATTCGAGTCACTCTTCTTCTTGCT-3′. All point mutations in pCMV-3Tag-3A-ADD1 were generated by the site-directed mutagenesis kit (QuikChange; Agilent Technologies) and were confirmed by dideoxy-DNA sequencing. The mutagenic primers for making mutations at S12, S355, S358, S465, and S726 were shown in Table S1. To construct the plasmid encoding the T7-tagged ADD1 head domain (aa 1–350) or Δtail (aa 1–430), cDNAs from pCMV-3Tag-3A-ADD1-head or pCMV-3Tag-3A-ADD1Δtail were subcloned into the pET-21d vector (EMD Millipore).

The pEGFP-Myo10 plasmid was a gift from B.S. Lee (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) and was described previously (Berg and Cheney, 2002). The full-length bovine Myo10 cDNA (aa 1–2,052) was amplified by PCR and cloned into pEGFP-C2 vector (Takara Bio Inc.). To construct the pEGFP plasmids encoding GFP-Myo10-N (aa 1–946) or GFP-Myo10-C (aa 946–2,052), the corresponding cDNA fragments were PCR amplified using pEGFP-Myo10 as the template with the following primers and were subcloned into the pEGFP-C3 vector (Takara Bio Inc.). For GFP-Myo10-N, the forward primer was 5′-CCCAAGCTTATGGACAACTTCTTCCCCGAG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-AAAAGTACTTTGAGCGACTCCAGGAACTCC-3′. For GFP-Myo10-C, the forward primer was 5′-CCCAAGCTTCTCAACTTCGACGAGATCGACGAG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-AAAAGTACTTCACCTGGAGCTGCCCTGGCTGCTC-3′. For GFP-Myo10 aa 1–748 (the motor domain), the forward primer was 5′-CCCAAGCTTATGGACAACTTCTTCCCCGAG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-CAAGATCTCACCATGGCCGCCCGCGTCAC-3′. To construct the pEGFP plasmids encoding GFP-Myo10 aa 1–439 or aa 440–748, the corresponding cDNA fragments were PCR amplified using pEGFP-Myo10 as the template with the following primers and were subcloned into the pEGFP-C1 vector (Takara Bio Inc.). For GFP-Myo10 aa 1–439, the forward primer was 5′-CAAGATCTATGGACAACTTCTTCCCCGAG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-CGGAATTCTTCAAATCCAAAGATGTCCAAG-3′. For GFP-Myo10 aa 440–748, the forward primer was 5′-CGAGATCTAACTTTGAGGTGAATCACTTTGAGCAG-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-CAGAATTCCACCATGGCCGCCCGCGT-3′.

To express the FLAG-ADD1 wild-type (WT) or S12A/S355A mutant by lentivirus infection, the corresponding cDNAs were PCR amplified using pCMV-3Tag-3A-ADD1 WT or pCMV-3Tag-3A-ADD1 S12A/S355A as the template with the following primers and were subcloned into the lentiviral vector pLKO.AS2.neomycin (neo; National RNAi Core Facility, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan). The forward primer was 5′-CTCGCTAGCATGAATGGTGATTCTCGTGCT-3′, and the reverse primer was 5′-CGTTTAAACCTATTTATCGTCATCATCTTTGTAGTCCTT-3′. To generate FLAG-ADD1 WT or S12A/S355A resistant to ADD1-specific shRNAs, two nucleotides, C1539T and T1542C, were substituted by site-directed mutagenesis in the pLKO.AS2.neo-FLAG-ADD1 WT or S12A/S355A construct with the forward primer 5′-CGAGAGCAGAATTTACAGGATATCAAGACGGCTGGCCCTCAG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-CTGAGGGCCAGCCGTCTTGATATCCTGTAAATTCTGCTCTCG-3′.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa, HEK293, HEK293T, and MDCK cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. HeLa S3 cells that stably expressed mCherry–histone H2B were a gift from D.W. Gerlich (Swiss Institute of Technology, Zurich, Switzerland) and were described previously (Steigemann et al., 2009). To generate the HeLa S3 cells, HeLa cells were transfected with pIRES-puro2B-mCherry–histone H2B and selected by puromycin. To synchronize HeLa cells in the G2/M phase, cells were treated with 200 ng/ml nocodazole for 16–18 h. To synchronize HEK293 cells in the G2/M phase, cells were treated with 300 ng/ml nocodazole for 16–18 h. For transient transfection, cells were seeded on 60-mm culture dishes for 18 h and were then transfected with plasmids using X-tremeGENE HP or Lipofectamine.

shRNA and lentiviral production

The lentiviral expression system and the pLKO-AS1-puromycin (puro) plasmid encoding shRNAs were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility (Academia Sinica, Taiwan). The target sequences for ADD1 were 5′-GCAGAATTTACAGGACATTAA-3′ (#1) and 5′-GCAGAATTTACAGGACATTAA-3′ (#2). The target sequences for Myo10 were 5′-CCCAGATGAGAAGATATTCAA-3′ (#1) and 5′-GATAGGACTTTCCACCTGATT-3′ (#2). For FLAG-ADD1 expression, FLAG-ADD1 cDNA was amplified by PCR and was subcloned into the pLKO-AS2-neo vector. To produce lentiviruses, HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 2.25 µg pCMV-ΔR8.91, 0.25 µg pMD.G, and 2.5 µg pLKO-AS1-puro-shRNA (or pLKO-AS2-neo-FLAG-ADD1) using Lipofectamine. After 3 d, the medium containing lentivirus particles was collected and stored at −80°C. Cells were infected with lentiviruses encoding shRNAs (or FLAG-ADD1) for 24 h and were subsequently selected in the growth medium containing 1.8–2.5 µg/ml puromycin (or 0.5 mg/ml G418).

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

To prepare whole-cell lysates, cells were lysed in 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM Na3VO4) containing protease inhibitors (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin, and leupeptin). For immunoprecipitation, aliquots of cell lysates were incubated with 1 µg anti-ADD1 (H-100) or 0.4 µg anti-GFP for 1.5 h at 4°C, and the immunocomplexes were precipitated by protein A–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). For the monoclonal antibody, protein A–Sepharose beads were precoupled with 1 µg rabbit anti–mouse IgG before use. The beads were washed three times with 1% NP-40 lysis buffer, boiled for 3 min in SDS sample buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose (Schleicher and Schuell). Immunoblotting was performed with the indicated antibodies using the Western chemiluminescent HRP substrate (Immobilon; EMD Millipore) for detection. Chemiluminescent signals were detected by ECL (Hyperfilm; GE Healthcare) or by a luminescence imaging system (LAS-3000; Fujifilm). To precipitate FLAG-ADD1, the cells were lysed in TBS buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, and 150 mM NaCl) containing protease inhibitors and subjected to centrifugation at 19,200 g at 4°C for 10 min. The cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity resins (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FLAG-ADD1 proteins were eluted from the resins with 100 µM 3× FLAG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich).

In vitro kinase assay

T7-tagged ADD1 head or Δtail (also with 6× His tag at the C terminus) were expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21) and were purified by Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified T7-ADD1 proteins were incubated with 10 ng of active CDK1/cyclin B1 in kinase buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM ATP) at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by SDS sample buffer, and the proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-ADD1 pS12 (1:2,000), anti-ADD1 pS355 (1:1,000), or anti-T7 (1:5,000).

Immunofluorescent staining and image analysis

For immunofluorescent staining, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in 90% methanol at −20°C for 30 min and were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min at room temperature. To stain FLAG-ADD1, the time for permeabilization was 10 min. The fixed cells were stained with primary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488– or Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used for immunofluorescent staining in this study were anti-ADD1 (H-100; 1:100), mouse anti–α-tubulin (DM1A; 1:500), and rabbit anti-FLAG (1:500). Coverslips were mounted in mounting medium (Anti-Fade Dapi-Fluoromount-G; SouthernBiotech). Images were acquired using a laser-scanning confocal microscope imaging system (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss) with a Plan Apochromat 63×, NA 1.4 oil immersion objective (Carl Zeiss). Images in Fig. 1 B were captured by a laser-scanning confocal microscope imaging system (LSM 780; Carl Zeiss) with a Plan Apochromat 63×, NA 1.4 oil immersion objective. Z sections were acquired at 0.3-µm steps, and optical sections were projected into one picture by ZEN 2011 software (Carl Zeiss). Images were cropped in Photoshop CS5 (Adobe) and were assembled by Illustrator CS5 (Adobe). The distribution of fluorescence intensity (Figs. 1 E, 2 A, and S2 C) was graphed using AxioVision Rel. 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss), and the histogram results were fit with a Gaussian distribution by Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software). The cell diameter and spindle length (pole to pole distance) were measured only in cells with two spindle poles at the same focal plane by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and were graphed by Prism 5 software. The histogram of the spindle length data was fit with a Gaussian distribution by Prism 5 software. The curved plot using Excel (Microsoft) was superimposed on the histogram (generated by Prism 5) by Illustrator CS5. All quantifications were derived from at least three independent experiments.

Live-cell imaging

HeLa S3 cells stably expressing histone H2B–mCherry (Steigemann et al., 2009) with or without ADD1 depletion were seeded on 0.17-mm glass coverslips. Cells were maintained in a microcultivation system with temperature and CO2 control devices (Carl Zeiss). The cells were monitored on an inverted microscope (Axio Observer.D1; Carl Zeiss) using a Plan Apochromat 40×, NA 1.4 objective. Images were captured every 3 min for 24 h using a digital camera (AxioCam MRm D; Carl Zeiss) and were analyzed by AxioVision Rel. 4.8 software. The 515–560-nm wavelength was used to excite mCherry. The 590–650-nm beam path filter was used to acquire images for the emission from mCherry. The duration from prophase (chromosome condensation) to anaphase onset was measured for ≥25 cells from three independent experiments.

MS

FLAG-ADD1 was transiently overexpressed in HEK293 cells, and the cells were synchronized in the G2/M phase by nocodazole. FLAG-ADD1 was bound to anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel and was eluted by 100 µM 3× FLAG peptides. FLAG-ADD1 and its interacting proteins were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and were stained with Coomassie blue. MS for the identification of protein IDs and phosphorylation sites was performed as previously described (Chan et al., 2010). In brief, nanoscale capillary liquid chromatography (LC)/tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) analysis was performed using an LC system (UltiMate Capillary; LC Packings) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (QSTAR; Applied Biosystems). A nanoelectrospray interface was used for LC-MS/MS analysis. Ionization (2.0-kV ionization potential) was performed with a coated nano-LC tip. Data acquisition was performed by automatic Information Dependent Acquisition (Applied Biosystems). The Information Dependent Acquisition automatically finds the most intense ions in a time-of-flight MS spectrum and then performs an optimized MS/MS analysis on the selected ions. The product ion spectra generated by nano–LC-MS/MS were searched against NCBI databases for exact matches using the MASCOT search program (Matrix Science).

Statistics

The Student’s t test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between two means. An asterisk indicates P < 0.05, and two asterisks indicate P < 0.01.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the association of ADD1 with mitotic spindles. Fig. S2 shows the identification of ADD1 phosphorylation sites in mitosis and their importance in the association with mitotic spindles. Fig. S3 shows that ADD1 does not directly interact with microtubules in vitro. Table S1 shows the mutagenic primers for making point mutations in ADD1. Video 1 shows the mitosis of control HeLa cells. Video 2 shows the mitosis of HeLa cells expressing shRNAs to luciferase. Video 3 shows the type I mitotic defect caused by ADD1 depletion. Video 4 shows the type II mitotic defect caused by ADD1 depletion. Video 5 shows the type III mitotic defect caused by ADD1 depletion. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201306083/DC1. Additional data are available in the JCB DataViewer at http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201306083.dv.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Daniel W. Gerlich for HeLa S3 cells and Dr. Beth S. Lee for the bovine Myo10 cDNA. We thank the Agricultural Biotechnology Research Center (Academia Sinica, Taiwan) for the LSM 780 laser-scanning microscope, the National RNAi Core Facility (Academia Sinica, Taiwan) for the lentiviral expression system, and the Biotechnology Center (National Chung Hsing University, Taiwan) for DNA sequencing and proteomics analysis.

This work was supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan (grant numbers NSC99-2628-B-005-010-MY3 and NSC102-2321-B-005-015-MY3); by the National Health Research Institutes, Taiwan (grant number NHRI-EX101-10103BI); and by the Aiming Top University plan from the Ministry of Education, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ADD

- adducin

- fps

- frames per second

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- MARCKS

- myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- Myo10

- myosin-X

- MyTH4

- myosin tail homology 4

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- WT

- wild type

References

- Abdi K.M., Bennett V. 2008. Adducin promotes micrometer-scale organization of beta2-spectrin in lateral membranes of bronchial epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:536–545 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett V., Gardner K., Steiner J.P. 1988. Brain adducin: a protein kinase C substrate that may mediate site-directed assembly at the spectrin-actin junction. J. Biol. Chem. 263:5860–5869 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J.S., Cheney R.E. 2002. Myosin-X is an unconventional myosin that undergoes intrafilopodial motility. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:246–250 10.1038/ncb762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg J.S., Derfler B.H., Pennisi C.M., Corey D.P., Cheney R.E. 2000. Myosin-X, a novel myosin with pleckstrin homology domains, associates with regions of dynamic actin. J. Cell Sci. 113:3439–3451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P.C., Sudhakar J.N., Lai C.C., Chen H.C. 2010. Differential phosphorylation of the docking protein Gab1 by c-Src and the hepatocyte growth factor receptor regulates different aspects of cell functions. Oncogene. 29:698–710 10.1038/onc.2009.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.L., Hsieh Y.T., Chen H.C. 2007. Phosphorylation of adducin by protein kinase Cdelta promotes cell motility. J. Cell Sci. 120:1157–1167 10.1242/jcs.03408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Avino P.P., Savoian M.S., Glover D.M. 2005. Cleavage furrow formation and ingression during animal cytokinesis: a microtubule legacy. J. Cell Sci. 118:1549–1558 10.1242/jcs.02335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Chapline C., Mousseau B., Fowler L., Ramsay K., Stevens J.L., Jaken S. 1995. 35H, a sequence isolated as a protein kinase C binding protein, is a novel member of the adducin family. J. Biol. Chem. 270:25534–25540 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field C.M., Wühr M., Anderson G.A., Kueh H.Y., Strickland D., Mitchison T.J. 2011. Actin behavior in bulk cytoplasm is cell cycle regulated in early vertebrate embryos. J. Cell Sci. 124:2086–2095 10.1242/jcs.082263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner K., Bennett V. 1986. A new erythrocyte membrane-associated protein with calmodulin binding activity. Identification and purification. J. Biol. Chem. 261:1339–1348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner K., Bennett V. 1987. Modulation of spectrin-actin assembly by erythrocyte adducin. Nature. 328:359–362 10.1038/328359a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazda L., Pokrzywa W., Hellerschmied D., Löwe T., Forné I., Mueller-Planitz F., Hoppe T., Clausen T. 2013. The myosin chaperone UNC-45 is organized in tandem modules to support myofilament formation in C. elegans. Cell. 152:183–195 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen G.G., Bretscher A. 2003. Cell biology. Microtubule asymmetry. Science. 300:2040–2041 10.1126/science.1084938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Roberts A.J., Leschziner A.E., Reck-Peterson S.L. 2012. Lis1 acts as a “clutch” between the ATPase and microtubule-binding domains of the dynein motor. Cell. 150:975–986 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C.A., Bennett V. 1995. Adducin: a physical model with implications for function in assembly of spectrin-actin complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18990–18996 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R., Bennett V. 1990. Mapping the domain structure of human erythrocyte adducin. J. Biol. Chem. 265:13130–13136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R., Gilligan D.M., Otto E., McLaughlin T., Bennett V. 1991. Primary structure and domain organization of human α and β adducin. J. Cell Biol. 115:665–675 10.1083/jcb.115.3.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerber M.L., Cheney R.E. 2011. Myosin-X: a MyTH-FERM myosin at the tips of filopodia. J. Cell Sci. 124:3733–3741 10.1242/jcs.023549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman P.A., Hughes C.A., Bennett V., Fowler V.M. 1996. A new function for adducin. Calcium/calmodulin-regulated capping of the barbed ends of actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7986–7991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Matsuoka Y., Bennett V. 1998. Adducin preferentially recruits spectrin to the fast growing ends of actin filaments in a complex requiring the MARCKS-related domain and a newly defined oligomerization domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19329–19338 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W., Elfrink K., Bähler M. 2010. Head of myosin IX binds calmodulin and moves processively toward the plus-end of actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 285:24933–24942 10.1074/jbc.M110.101105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y., Hughes C.A., Bennett V. 1996. Adducin regulation. Definition of the calmodulin-binding domain and sites of phosphorylation by protein kinases A and C. J. Biol. Chem. 271:25157–25166 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y., Li X., Bennett V. 1998. Adducin is an in vivo substrate for protein kinase C: phosphorylation in the MARCKS-related domain inhibits activity in promoting spectrin–actin complexes and occurs in many cells, including dendritic spines of neurons. J. Cell Biol. 142:485–497 10.1083/jcb.142.2.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney R.J., Vershinin M., Kunwar A., Vallee R.B., Gross S.P. 2010. LIS1 and NudE induce a persistent dynein force-producing state. Cell. 141:304–314 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mische S.M., Mooseker M.S., Morrow J.S. 1987. Erythrocyte adducin: a calmodulin-regulated actin-bundling protein that stimulates spectrin-actin binding. J. Cell Biol. 105:2837–2845 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsushima M., Aoki K., Ebisuya M., Matsumura S., Yamamoto T., Matsuda M., Toyoshima F., Nishida E. 2010. Revolving movement of a dynamic cluster of actin filaments during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 191:453–462 10.1083/jcb.201007136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naydenov N.G., Ivanov A.I. 2010. Adducins regulate remodeling of apical junctions in human epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:3506–3517 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J., Cramer L.P., Baum B., McGee K.M. 2004. Myosin II-dependent cortical movement is required for centrosome separation and positioning during mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. 117:361–372 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00341-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman-Gavrila R.V., Forer A. 2000. Evidence that actin and myosin are involved in the poleward flux of tubulin in metaphase kinetochore microtubules of crane-fly spermatocytes. J. Cell Sci. 113:597–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steigemann P., Wurzenberger C., Schmitz M.H., Held M., Guizetti J., Maar S., Gerlich D.W. 2009. Aurora B-mediated abscission checkpoint protects against tetraploidization. Cell. 136:473–484 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima F., Nishida E. 2007. Integrin-mediated adhesion orients the spindle parallel to the substratum in an EB1- and myosin X-dependent manner. EMBO J. 26:1487–1498 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeki N., Jung H.S., Sakai T., Sato O., Ikebe R., Ikebe M. 2011. Phospholipid-dependent regulation of the motor activity of myosin X. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18:783–788 10.1038/nsmb.2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velarde N., Gunsalus K.C., Piano F. 2007. Diverse roles of actin in C. elegans early embryogenesis. BMC Dev. Biol. 7:142 10.1186/1471-213X-7-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K.L., Sokac A.M., Berg J.S., Cheney R.E., Bement W.M. 2004. A microtubule-binding myosin required for nuclear anchoring and spindle assembly. Nature. 431:325–329 10.1038/nature02834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolner S., Papalopulu N. 2012. Spindle position in symmetric cell divisions during epiboly is controlled by opposing and dynamic apicobasal forces. Dev. Cell. 22:775–787 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolner S., O’Brien L.L., Wiese C., Bement W.M. 2008. Myosin-10 and actin filaments are essential for mitotic spindle function. J. Cell Biol. 182:77–88 10.1083/jcb.200804062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.