Abstract

The purpose of this study was to cross-validate measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity made with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurements to those made with phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS). Sixteen young (age = 22.5 ± 3.0 yr), healthy individuals were tested with both 31P-MRS and NIRS during a single testing session. The recovery rate of phosphocreatine was measured inside the bore of a 3-Tesla MRI scanner, after short-duration (∼10 s) plantar flexion exercise as an index of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. Using NIRS, the recovery rate of muscle oxygen consumption was also measured using repeated, transient arterial occlusions outside the MRI scanner, after short-duration (∼10 s) plantar flexion exercise as another index of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity. The average recovery time constant was 31.5 ± 8.5 s for phosphocreatine and 31.5 ± 8.9 s for muscle oxygen consumption for all participants (P = 0.709). 31P-MRS time constants correlated well with NIRS time constants for both channel 1 (Pearson's r = 0.88, P < 0.0001) and channel 2 (Pearson's r = 0.95, P < 0.0001). Furthermore, both 31P-MRS and NIRS exhibit good repeatability between trials (coefficient of variation = 8.1, 6.9, and 7.9% for NIRS channel 1, NIRS channel 2, and 31P-MRS, respectively). The good agreement between NIRS and 31P-MRS indexes of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity suggest that NIRS is a valid method for assessing mitochondrial function, and that direct comparisons between NIRS and 31P-MRS measurements may be possible.

Keywords: mitochondrial capacity, 31P-MRS, oxidative metabolism, mitochondrial function

the mitochondrion is a dual-membrane organelle that is vital for maintaining proper cell function. Mitochondria have several roles, including cellular growth and differentiation, apoptosis, and cellular signaling, but are most known for their metabolic capability to generate chemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (25). In skeletal muscle, mitochondria generate most of the fuel required for contractile activity and physical functioning, under normal conditions. Both the number of mitochondria and the function of mitochondria are related to exercise performance (11, 14, 15). Reduced mitochondrial function and/or density is also associated with several pathological conditions, including diabetes (16, 30), aging (6, 22), and neuromuscular diseases (17, 20, 24, 38). Because of the importance of mitochondrial function on both health and physical performance, the development of novel, cost-effective methodologies to study mitochondrial health is critical.

Traditionally, mitochondrial function has been studied using methods that can be classified into two categories: invasive (ex vivo) or noninvasive (in vivo) approaches. Ex vivo approaches involve a small biopsy of muscle tissue to measure enzyme concentrations or activity levels (11, 14), isolated mitochondrial preparations (5), or permeabilized muscle fiber preparations (10). Until recently, in vivo approaches to studying mitochondrial function have been limited to the use of magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to study changes in phosphorus (31P) metabolites during exercise and the recovery postexercise (4). The most widely used 31P-MRS assessment for mitochondrial function is the recovery rate of phosphocreatine (PCr) following exercise. Using the assumption of equilibrium for the creatine kinase reaction, the recovery rate of PCr after exercise is a function of mitochondrial ATP production, which has been validated against in vitro measurements of enzyme activity (19, 21, 29) and high-resolution respirometry (18).

Alternatively, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has been used to investigate muscle blood flow and oxidative metabolism both at rest and during different types of exercises. It has been shown by our laboratory and others that oxidative metabolism, measured by NIRS, increases linearly with exercise intensity (32, 36). Previous studies have compared the recovery of O2Hb (oxygenated hemoglobin/myoglobin) and/or Hbdiff (O2Hb − HHb, where HHb represents deoxygenated hemoglobin/myoglobin) after exercise with the recovery kinetics of PCr (13, 23). Interestingly, the findings of these studies are contradictory. McCully et al. (23) reported “good agreement” between the time constants for the recovery of PCr and O2Hb after submaximal exercise intensities, but not for the recovery after maximal exercise intensities. Although there was a strong correlation in the study by McCully et al., they did report that the time constants for the recovery of O2Hb were faster than PCr in all participants. Surprisingly, Hanada et al. (13) did not find a correlation between the time constants of PCr and O2Hb recovery in either healthy controls or patients with heart failure. These somewhat conflicting results can be explained by the fact that the recovery of O2Hb is not actually a measurement of oxidative metabolism, but rather a combination of oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption. For these reasons, our laboratory and others have recently utilized a novel, in vivo approach to measuring skeletal muscle mitochondrial function using NIRS (26, 27, 33). This approach uses NIRS in combination with a rapid cuff inflation system (used to block oxygen delivery and venous return) to measure kinetic changes in skeletal muscle oxygen consumption (mV̇o2) after submaximal exercise. This approach is different from that used by McCully et al. (23) and Hanada et al. (13) because the arterial occlusions isolate oxygen consumption from oxygen delivery, whereas the recovery of NIRS signals without arterial occlusions represents the recovery of an oxygen debt and is influenced by both the rate of oxygen consumption and the rate of oxygen delivery. Similar to PCr recovery, the recovery of mV̇o2 (using arterial occlusions) after exercise should be a function of mitochondrial ATP production and, therefore, has the potential to be used as a measure of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity (26). This NIRS approach has been shown to be reproducible (33) and independent of exercise intensity (32), detects the expected differences between untrained and trained individuals (3), as well as paralyzed and nonparalyzed individuals (8), and can track changes in mitochondrial function with exercise training and detraining (34). In the present study, we cross-validated NIRS measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity with 31P-MRS measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in a population of young healthy adults. Because the repeatability of measurements can affect the level of agreement, we also assessed the repeatability of both NIRS and 31P-MRS measurements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Sixteen healthy participants (10 men, 6 women), ages 19–30 yr, were tested in this study. The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board at the University of Georgia (Athens, GA), and all subjects gave written, informed consent before testing.

Study Design

NIRS and 31P-MRS testing was performed on all participants (in random order) in a single visit to the University of Georgia BioImaging Research Center (Athens, GA). The NIRS and 31P-MRS testing protocols took ∼30 min each.

NIRS Experimental Protocol

NIRS testing performed in this study is similar to that describe in previous studies (32, 33). Each subject was placed on a padded table with both legs extended (0° of knee flexion). The participant's dominant foot was placed into a home-built nonmagnetic pneumatic exercise device, similar to that used in previous studies (23, 39). The foot was strapped firmly to the exercise device using nonelastic Velcro straps proximal to the base of the fifth digit, and the knee was supported. The NIRS optode was placed at the level of the largest circumference of the triceps surae, specifically over the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle and secured with Velcro straps and biadhesive tape. A blood pressure cuff (Hokanson SC12D, Bellevue, WA) was placed proximal to the NIRS optode above the knee joint. The blood pressure cuff was connected to a rapid-inflation system (Hokanson E20, Bellevue, WA). Adipose tissue thickness (ATT) was measured at the site of the NIRS optode using B-mode ultrasound (LOGIQ e; GE HealthCare). Participants were asked not to consume caffeine or tobacco on the day of the test or to use alcohol or perform moderate or heavy physical activity for at least 24 h before the test.

The test protocol consisted of two measurements of resting mV̇o2 by way of inflation of a blood pressure cuff (250–300 mmHg) for 30 s. For the recovery measurements, 10 s of plantar flexion exercise were performed at a given resistance [pneumatic resistance in the form of pounds per square inch (psi)] to increase mV̇o2. The resistance was set during a familiarization session before testing to a level that would produce the optimal balance between force and speed of contractions. For example, the participants were expected to perform plantar flexions at the highest psi (air resistance) that would allow for a minimum of 2 contractions/s. The average resistance was 19 ± 4 psi (range = 12–25 psi). Previous studies have shown short-duration exercise produces similar rates of PCr resynthesis (39). Following the plantar flexion exercise, a series of 10–18 brief (5–10 s) arterial occlusions were applied to measure the rate of recovery of mV̇o2 back to resting levels. There was a small time delay between the end-exercise and initial arterial occlusion (∼2 s) due to movement of the exercise ergometer as the pressure dissipated from the air cylinder. To maximize our ability to measure the recovery of mV̇o2 while minimizing the discomfort to participants, the duration between arterial occlusions began at 5 s and extended to 20 s by the end of the repeated occlusions (i.e., 5 s on/5 s off for cuffs 1–6, 7 s on/7 s off for cuffs 7–10, 10 s on/15 s off for cuffs 11–14, and 10 s on/20 s off for cuffs 15–18). The exercise and repeated cuffing procedure was repeated a second time, with ∼5–7 min in between the first and second exercise/recovery bouts.

An ischemic calibration procedure was performed before the recovery measurements and used to scale the NIRS O2Hb, HHb, and Hbdiff signals to the maximal physiological range, as previously described (32).

NIRS device.

NIRS signals were obtained using a continuous-wave NIRS device (Oxymon MKIII, Artinis Medical Systems). The probe was set to have two source-detector separation distances (between 30 and 45 mm), with the smallest source-detector distance set to approximately twice the ATT. The second source-detector distance was always 1 cm greater than the first. NIRS data were collected at 10 Hz.

Calculation of mV̇o2.

mV̇o2 was calculated as the slope of change in the Hbdiff signal (Hbdiff = O2Hb − HHb) during the arterial occlusion using simple linear regression. mV̇o2 was expressed as a percentage of the ischemic calibration per unit time. This measurement was made at rest and repeated a number of times after exercise. The postexercise repeated measurements of mV̇o2 were fit to a monoexponential curve according to the formula below:

| (1) |

For this equation, y is relative mV̇o2 during the arterial occlusion, End is the mV̇o2 immediately after the cessation of exercise, Δ is the change in mV̇o2 from rest to end exercise, and k is the fitting rate constant, t is the time.

Correction for blood volume.

NIRS data were analyzed using custom-written routines for Matlab version 7.13.0.564 (The Mathworks, Natick, MA). NIRS signals were corrected for changes in blood volume using the following method, as previously described (33).

Calculation of signal-to-noise ratio.

The quality of NIRS data was determined by calculating a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The SNR was calculated for each arterial occlusion on all data. The signal was calculated as the change in the NIRS signal during the chosen measurement period of an arterial occlusion and is, therefore, a function of the duration of the occlusion and the rate of oxygen consumption. The noise was calculated as the standard deviation of 600 data points (60 s).

31P-MRS Experimental Protocol

Subjects were tested in a 3-Tesla whole-body magnet (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). A 1H and 31P radio-frequency dual-surface coil (Clinical MR Solutions, Brookfield, WI) was placed over the medial gastrocnemius muscle of the subject's dominant leg. The size of the 31P coil was 13 cm × 13 cm, placed orthogonal to the 1H coil (two loops, side by side, 20 cm × 20 cm in size). Manual shimming on 1H was applied to get a better SNR and less spectrum distortion, after an auto-shimming by a prescan sequence [all subjects 1H full width half maximum (FWHM) mean ± SD; 0.60 ± 0.14 ppm]. A nonlocalized, single pulse-acquisition pulse sequence was applied to acquire the 31P spectrum with the following scan parameters: repetition time (TR) = 3 s, field of view = 8 cm, slice thickness = 8 cm, number of excitation = 1, RF pulse = hard. The field of view and slice thickness correspond to the shimming volume (33).

Metabolic calculations.

Resting spectra were acquired every 3 s until 50 scans are taken. The resulting spectra were summed in a custom analysis program (Winspa, Ronald Meyer, Michigan State University). The summed spectrum was apodized using 5-Hz exponential line broadening, and zero-filled from 2,048 to 8,192 points. The area under the curve for each peak (Pi, PCr, α-ATP, β-ATP, and γ-ATP) was determined using integration. Absolute concentrations were calculated using the assumed value of 8.2 mM for the γ-ATP peak. Saturation effects were corrected for using fully relaxed spectra collected from four individuals using the same pulse sequence above, except the TR was changed to 15 s. Muscle pH was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

where Pishift is the chemical shift of Pi relative to PCr in parts per million (ppm).

Exercise Protocol

Plantar flexion exercise in a home-built nonmagnetic pneumatic ergometer was performed inside the bore of the MRI. Identical resistances (psi) were used for 31P-MRS and NIRS testing. The exercise protocol consisted of ∼45 s of rest, followed by ∼10 s of rapid plantar flexion, and ∼4 min for the measurement of the resynthesis of PCr. 31P spectra were obtained using the same pulse sequence characteristics described above. This short-duration exercise bout was designed to decrease PCr concentration ([PCr]) without causing significant acidosis.

PCr recovery.

[PCr] values were determined from the peak heights from individual spectra (temporal resolution of 3 s) using custom-written routines in Matlab version 7.13.0.564 (The Mathworks, Natick, MA) (24). Individual spectra were apodized using 2-Hz exponential line broadening, followed by zero-filling to 8,192 points. Peak heights were determined using the magnitude of each spectrum. The assumption that changes in peak height represent changes in concentration is only valid when there is no change in the peak widths (FWHM). FWHM of each PCr peak was calculated to ensure no changes in magnetic field homogeneity occurred during the recovery period. PCr peak heights during recovery after exercise were fit to an exponential curve.

| (3) |

where PCrend is the percent PCr immediately after cessation of exercise, ΔPCr is the change in PCr from rest to end exercise, and k is the fitting rate constant, and t is the time. The maximal rate of ATP synthesis (Qmax) was calculate using the following equation:

| (4) |

where [PCr]resting is the resting concentration of PCr, and kPCr is the rate constant for the recovery of PCr after exercise.

Calculation of SNR

The quality of phosphorus data collected was determined by calculating a SNR for each individual spectra. The signal was calculated as the peak height of PCr for each spectra (TR = 3 s). After apodization (5-Hz exponential filtering), the resulting spectra were zero-filled (from 2,048 to 8,192 points) and Fourier transformed. The noise was calculated as the standard deviation of the first 3,000 data points of the spectra.

Comparison of Peak Heights Analysis and AMARES

The peak heights analysis approach described above was directly compared with a commonly used time-domain fitting algorithm, Advanced Method for Accurate, Robust and Efficient Spectral fitting (AMARES) with prior knowledge (37), using the freely available JMRUI software (28). The recovery of PCr after exercise was determined using both AMARES and the peak heights approach. The sum of squared residuals between the monoexponential curve fit and [PCr] was used to evaluate the quality of curve fitting. For resting phosphorus scans, the [PCr] was calculated for individual spectra (N = 50 scans per participant) using both analytic approaches. The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for the [PCr] using both approaches.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Test-retest reliability was analyzed using CV and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC model 1,1). CV was expressed as a percentage. PCr time constants were compared with NIRS time constants using a two-tailed Student's t-test for paired samples. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the relationship between two variables. Bland-Altman limits of agreement analysis was performed to determine the level of agreement between two variables (1). Statistical analyses were performed using either SPSS 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) or GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Significance was accepted when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

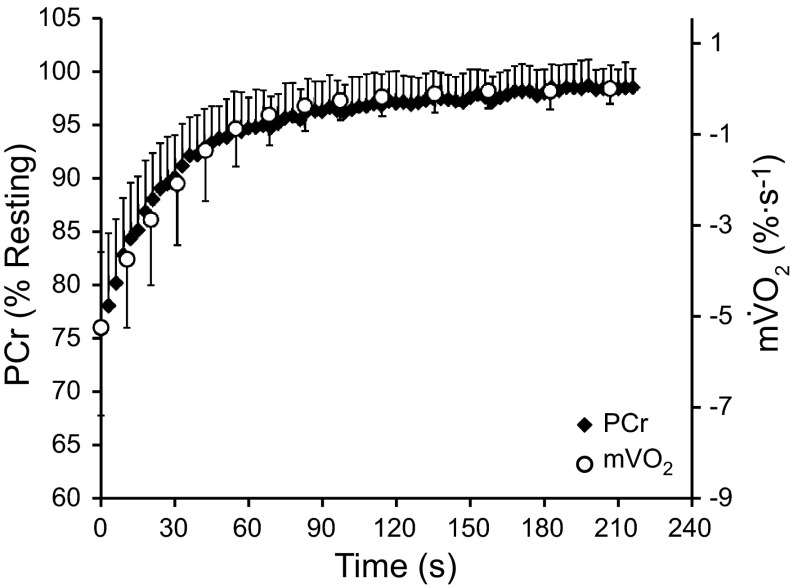

All participants completed testing without any adverse events. The physical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The group average recovery of mV̇o2 is shown in Fig. 1, overlapped with the recovery of PCr (error bars represent SD).

Table 1.

Physical characteristics of the participants

| Optode Distance, mm |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Height, cm | Weight, kg | Age, yr | ATT, mm | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | |

| Men | 10 | 179.1 ± 6.4 | 79.9 ± 12.2 | 23.0 ± 3.2 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | ||

| Women | 6 | 168.1 ± 9.6 | 68.1 ± 11.6 | 21.6 ± 2.6 | 9.1 ± 3.4 | ||

| Total | 16 | 174.9 ± 9.2 | 75.5 ± 13.0 | 22.5 ± 3.0 | 7.2 ± 2.8 | 30/35 (n = 10/6) | 40/45 (n = 10/6) |

Values are means ± SD; n, no. of subjects. ATT, adipose tissue thickness. Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) optode distances used and their corresponding frequency of use are shown for informational reasons. Statistical comparisons between sexes were not performed.

Fig. 1.

Recovery of phosphocreatine (PCr) and muscle oxygen consumption (mV̇o2) after short-duration plantar flexion exercise. Values are mean of all participants (n = 16) and all trials ± SD.

31P-MRS

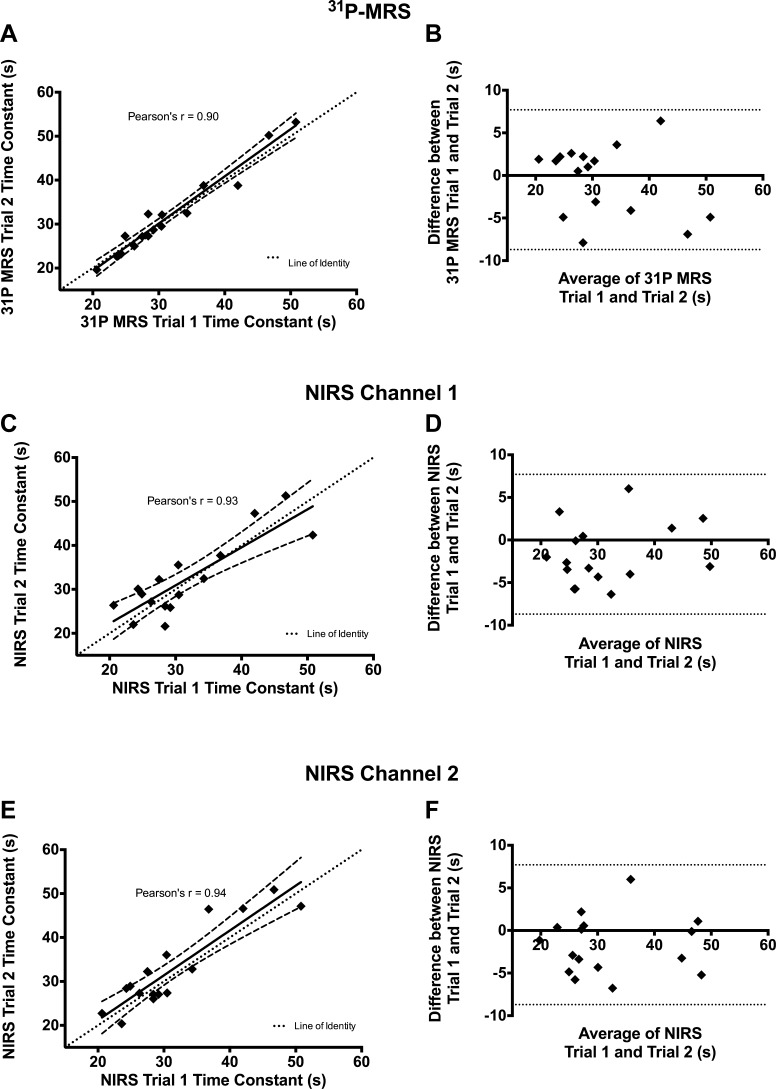

The average recovery time constant for PCr was 31.5 ± 8.5 s for all participants. The recovery rate was reproducible between trials (CV = 7.6%, ICC = 0.90). Comparisons between trials for the PCr recovery time constant are shown in Fig. 2A. The corresponding Bland-Atlman plot is shown in Fig. 2B. During the 10 s of rapid plantar flexion exercise, [PCr] decreased by ∼24%.

Fig. 2.

Repeatability and reproducibility of phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy (31P-MRS) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) data. Correlations between trials are shown for 31P-MRS (A), NIRS channel 1 (C), and NIRS channel 2 (E). For A, C, and E, the dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals for the regression equation. Corresponding Bland-Altman plots are shown for 31P-MRS (B), NIRS channel 1 (D), and NIRS channel 2 (F). For Bland-Altman plots, dotted lines represent the 95% limits of agreement.

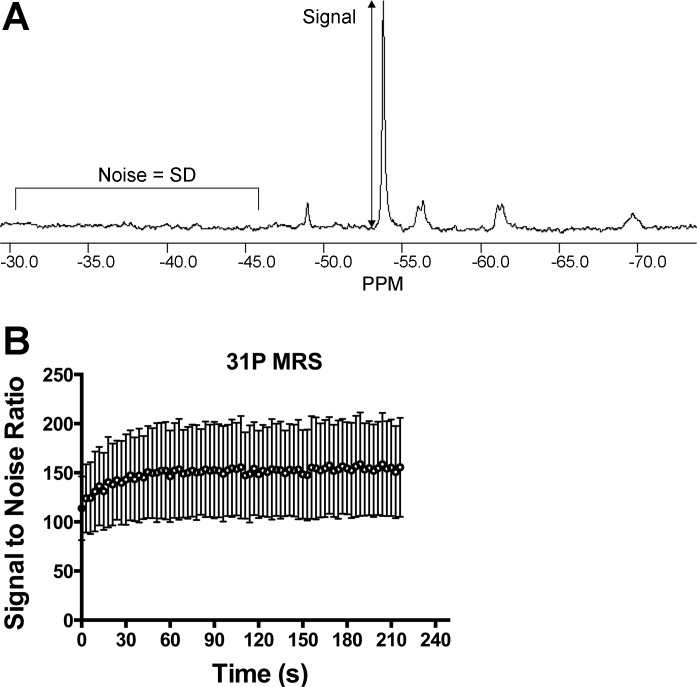

The resting and end-exercise values for [PCr] and pH are shown in Table 2. FWHM of PCr was calculated for each spectra, on all tests, and did not change throughout the recovery from exercise (data not shown). The average SNR of resting phosphorus spectra was 154 ± 47. During the recovery of PCr, the SNR increased as PCr is resynthesized (Fig. 3). We did not find a strong relationship between the variability of the time constant (CV) and SNR for 31P-MRS (R2 < 0.07).

Table 2.

Resting and end-exercise [PCr] and pH

| Resting |

End Exercise |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [PCr] | pH | [PCr] | pH (minimum) | |

| All participants | 34.25 ± 2.86 | 7.05 ± 0.03 | 25.89 ± 2.96 | 7.01 ± 0.07 (6.98 ± 0.06) |

Values are means ± SD. [PCr], phosphocreatine concentration. End-exercise pH was calculated from the first phosphorus spectra during the recovery measurements. The minimum pH is the lowest pH recorded during the recovery measurements.

Fig. 3.

Signal-to-noise analysis of 31P-MRS data. A: a single free induction decay, after apodization, zero filling, and Fourier transformation. B: average signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) during the postexercise recovery for all participants and all trials. Values are means ± SD.

NIRS

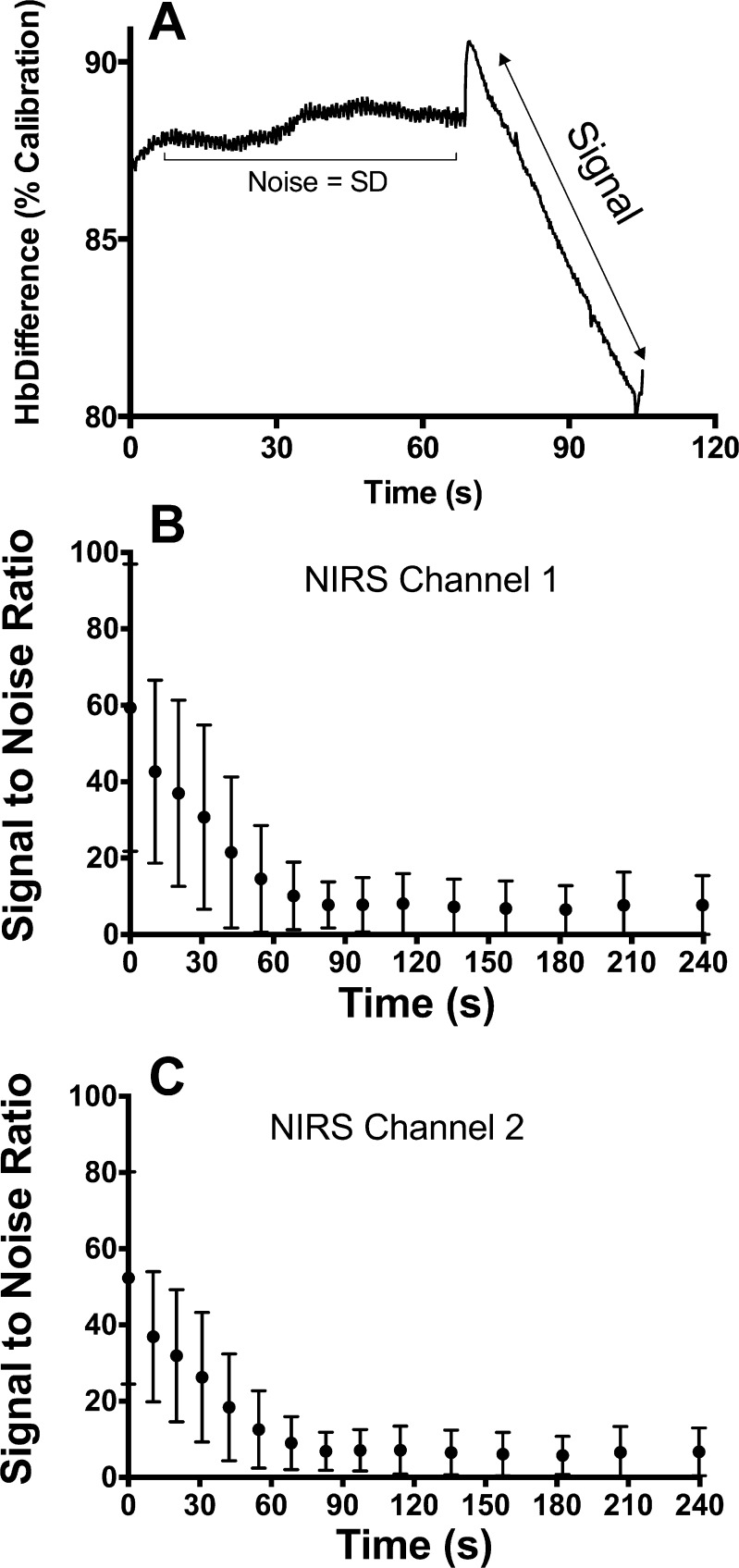

The resting value for mV̇o2 was 0.26 ± 0.10%/s for all participants. The average time constant for the recovery of mV̇o2 after exercise was 31.5 ± 8.9 s. The time constant was reproducible between trials for both channels of NIRS device (CV = 8.1 and 6.1%, ICC = 0.93 and 0.95, for channel 1 and channel 2, respectively). The trials were also well correlated with each other for channel 1 (Pearson's r = 0.93, P < 0.0001) and channel 2 (Pearson's r = 0.94, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2, C and E). Corresponding Bland-Altman plots for the trials of NIRS channel 1 and channel 2 are shown in Fig. 2, D and E, respectively. Statistical values regarding the repeatability of NIRS measurements are shown in Table 3. The SNR for NIRS measurements of mV̇o2 decreased as mV̇o2 returned to resting levels (Fig. 4). The average SNR for resting mV̇o2 was 7.38 ± 7.06 for channel 1 and 6.34 ± 5.94 for channel 2. We did not find a strong relationship between the variability of the time constant (CV) and SNR for NIRS (R2 < 0.1).

Table 3.

Metabolic parameters for NIRS and 31P-MRS

| Trial 1 | Trial 2 | CV (Range), % | ICC | Pearson's r | P (Paired t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIRS parameters | ||||||

| Channel 1 | ||||||

| End-exercise mV̇o2, %/s | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 5.4 ± 2.0 | 9.8 (0.2–57.4) | 0.85 | 0.827 | 0.311 |

| Time constant, s | 30.5 ± 9.5 | 32.2 ± 8.6 | 8.1 (0.2–15.7) | 0.93 | 0.936 | 0.599 |

| Time constant, 95% CI | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.8 | − (0.3–6.6) | |||

| kmV̇o2, s−1 | 0.0353 ± 0.0091 | 0.0329 ± 0.0078 | 8.1 (0.2–15.7) | 0.93 | 0.838 | 0.513 |

| Channel 2 | ||||||

| End-exercise mV̇o2, %/s | 5.2 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 2.0 | 8.9 (0.2–52.1) | 0.83 | 0.813 | 0.289 |

| Time constant, s | 31.2 ± 9.7 | 33.0 ± 9.6 | 6.9 (0.2–15.7) | 0.95 | 0.925 | 0.720 |

| Time constant, 95% CI | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 2.0 | − (0.3–7.5) | |||

| kmV̇o2, s−1 | 0.0347 ± 0.0095 | 0.0326 ± 0.0085 | 6.9 (0.2–15.7) | 0.95 | 0.936 | 0.164 |

| 31P-MRS parameters | ||||||

| End-exercise PCr, mM | 25.7 ± 3.0 | 26.0 ± 3.0 | 3.8 (0.4–12.9) | 0.87 | 0.848 | 0.463 |

| End-exercise pH | 7.00 ± 0.08 | 7.02 ± 0.06 | 0.3 (0.0–1.1) | 0.86 | 0.896 | 0.150 |

| Time constant, s | 31.3 ± 8.2 | 31.8 ± 9.4 | 7.6 (1.3–19.7) | 0.90 | 0.896 | 0.639 |

| Time constant, 95% CI | 3.2 ± 2.9 | 2.6 ± 1.5 | − (0.5–11.9) | |||

| kPCr, s−1 | 0.0338 ± 0.0078 | 0.0337 ± 0.0086 | 7.6 (1.3–19.7) | 0.90 | 0.862 | 0.946 |

| Qmax, mM ATP/s | 1.16 ± 0.28 | 1.16 ± 0.32 | 7.6 (2.3–19.7) | 0.89 | 0.883 | 0.999 |

Values are means ± SD. 31P-MRS, phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy; CV, coefficient of variation; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; mV̇o2, muscle oxygen consumption; kmV̇o2, rate constant for the recovery of mV̇o2; kPCr, rate constant for the recovery of PCr; Qmax, maximal rate of ATP synthesis (in mM ATP/s); 95% CI, 95% confidence interval for curve fitting in seconds. Student's Paired t-test was performed between trials.

Fig. 4.

Signal-to-noise analysis of NIRS data. A: sample NIRS signal showing how the SNR was calculated. SNRs for each postexercise arterial occlusions are shown for channel 1 (B) and channel 2 (C). Values in B and C are the average of all participant and all trials ± SD.

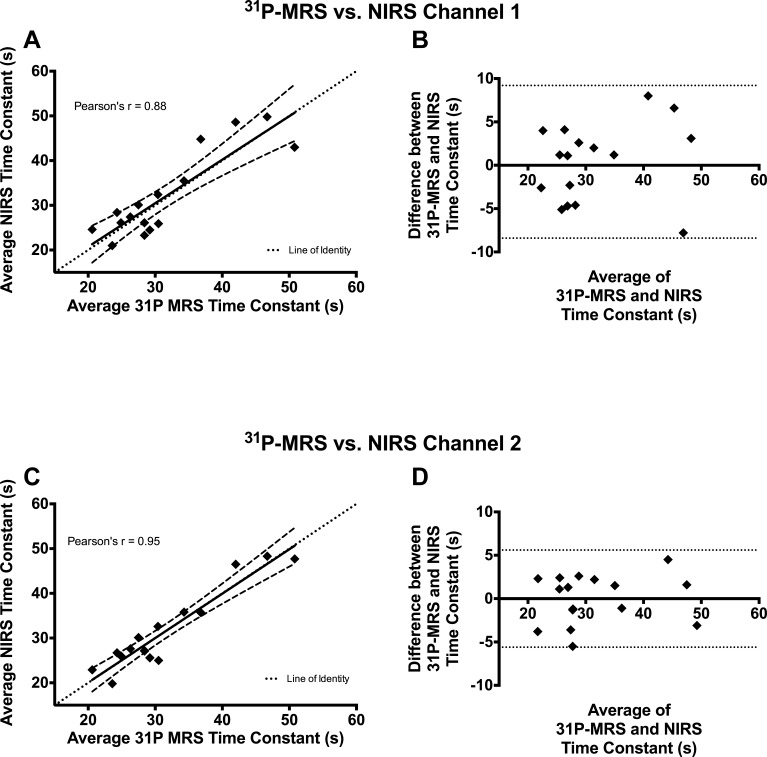

Relationship Between NIRS and 31P-MRS

The rate of recovery of mV̇o2 measured by NIRS correlated well with the rate of recovery of PCr measured by 31P-MRS. Using the average time constant for both trials, 31P-MRS correlated well with NIRS for both channel 1 (Pearson's r = 0.88, P < 0.0001) and channel 2 (Pearson's r = 0.95, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5, A and B). Bland-Altman plots (Fig. 5, B and C) of the time constants show that the errors (differences between NIRS and 31P-MRS time constants) were approximately symmetrically distributed around zero, with no indication of a systematic bias between measurement techniques.

Fig. 5.

Comparison between 31P-MRS and NIRS data. All comparisons were made by averaging the time constants for both trials. Correlations between 31P-MRS and NIRS channel 1 (A) and NIRS channel 2 (C) are shown, where dashed lines represent the 95% confidence intervals for the regression equation. Corresponding Bland-Altman plots for comparisons between 31P-MRS and NIRS channel 1 (B) and NIRS channel 2 (D) are also shown, with the dotted lines indicating the 95% limits of agreement.

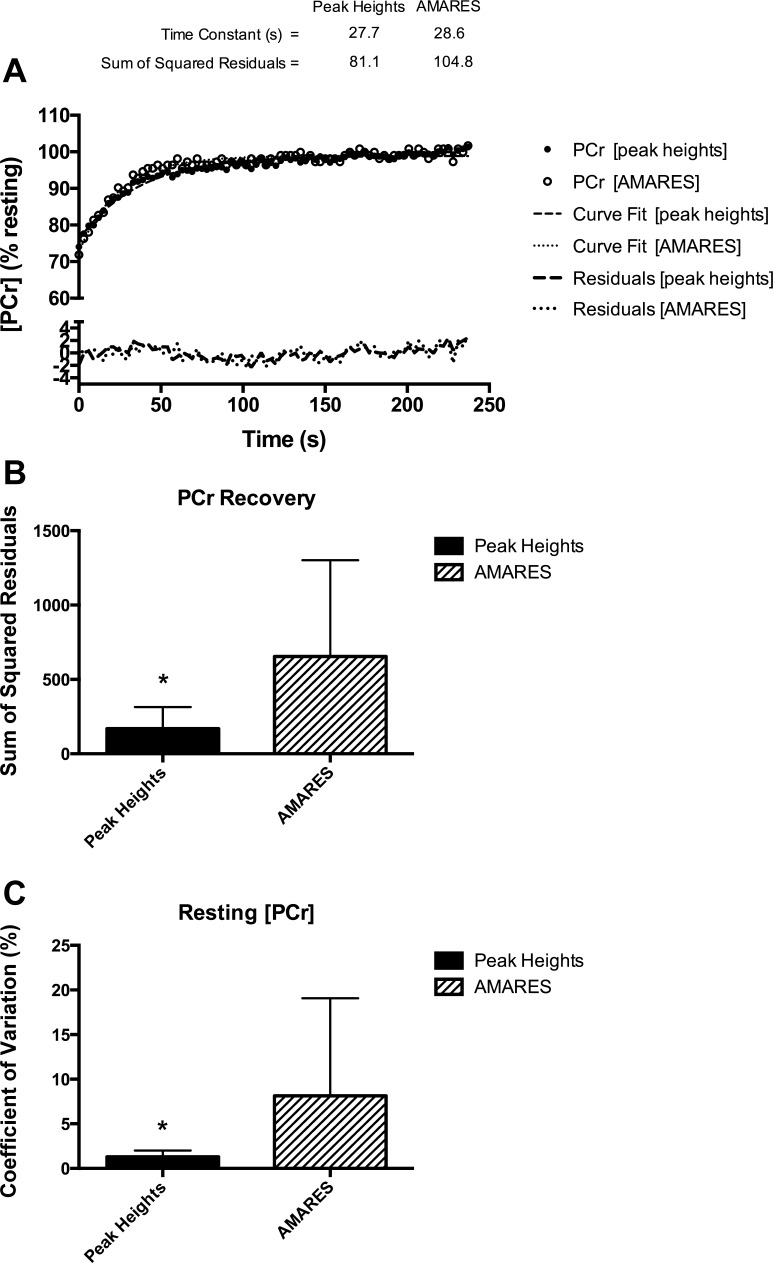

Comparison of Peak Heights and AMARES

An example from one participant of PCr recovery kinetics analyzed using the peak heights approach and AMARES is shown in Fig. 6A. The sum of squared residuals between the measured [PCr] and the monoexponential curve fit was significantly smaller (P < 0.001) with the peak heights approach, indicating a better quality fit (Fig. 6B). The reproducibility of peak heights analysis was determined from the resting scan (50 spectra per participant). The mean CV of PCr peak heights was 1.3 ± 0.7% (range = 0.6–2.9%) and 8.1 ± 10.9% (range = 0.96–21.0%) for AMARES (P = 0.02) (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

A: comparison between peak heights and Advanced Method for Accurate, Robust and Efficient Spectral fitting (AMARES) analysis approaches. B: the sum of squared residuals between the measured PCr concentration ([PCr]) and the monoexponential curve fit was significantly lower using the peak heights analysis. C: the variance of resting PCr peaks was also significantly lower using the peak height approach. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study found that NIRS-measured recovery kinetics of mV̇o2 were not statistically different from and correlated well with 31P-MRS-measured recovery kinetics of PCr after short-duration exercise. Furthermore, both NIRS and 31P-MRS measurements exhibited excellent reproducibility in the current experimental conditions. The level of agreement between NIRS and 31P-MRS is similar to a previous study. Nagasawa et al. (27) made similar measurements in the forearm muscles of eight male participants, reporting a similar relationship between NIRS and 31P-MRS recovery kinetics (r = 0.92). In contrast to the present study, the study by Nagasawa and colleagues did not utilize a correction for blood volume shifts, which has been shown to reduce the variability of NIRS time/rate constants with continuous-wave NIRS devices (33). Nonetheless, our findings support those reported by Nagasawa et al. (27). The recovery time constants in the present study (31.5 ± 8.5 s for PCr and 31.5 ± 8.9 s for NIRS) are also similar to those reported by previous studies using 31P-MRS in untrained individuals (9, 19, 39).

NIRS measurements of mV̇o2 have been quantitatively validated using 31P-MRS in both resting and exercising skeletal muscle (12, 35). Hamaoka et al. (12) utilized arterial occlusions to measure mV̇o2 with NIRS and quantified the NIRS mV̇o2 using the rate of PCr breakdown at rest (as a indication of ATP consumption). These authors also reported strong linear relationships between mV̇o2 and both [ADP] and [PCr], consistent with kinetic and thermodynamic models of respiration. Using a similar experimental design, Sako et al. (35) quantified NIRS measured mV̇o2 during various levels of exercise intensity using a similar “calibration” with resting metabolism measurements with NIRS and 31P-MRS. After quantification, Sako et al. (35) reported a strong correlation between NIRS and 31P-MRS measurements of muscle oxidative metabolism. While both of these studies have important findings and support NIRS as a valid tool for assessing muscle oxidative metabolism noninvasively, the methodology used is such that NIRS in combination with 31P-MRS provides valid measurements. In contrast, the present study demonstrates clearly that the NIRS-based recovery kinetics of mV̇o2, using repeated arterial occlusions, can provide an index of the maximal oxidative capacity of skeletal muscle (i.e., time constant or rate constant), which is measured independent of 31P-MRS, but is both similar and well correlated with 31P-MRS. These findings, in combination with those by Nagasawa et al. (27), suggest that NIRS could be used to study muscle metabolism in vivo, when 31P-MRS is not available. Importantly, the use of repeated arterial occlusions to measure the recovery kinetics of oxygen consumption provides a more direct measurement oxidative metabolism compared with previous studies that measured the recovery kinetics of NIRS signals (mainly O2Hb or oxygen saturation), which provides information about the balance of oxygen consumption and oxygen delivery (13, 23).

The direct comparisons between NIRS and 31P-MRS in this study were made using a convenience sample of young healthy, college-aged individuals. This sample of individuals was chosen to achieve the highest quality of data possible. For this reason, we have also calculated SNR measurements for both NIRS and 31P-MRS. Some potential factors that could influence the SNR of 31P-MRS data include the following: leg positioning compared with the isocenter of the magnet, coil positioning and loading, shim quality, muscle composition (intramuscular fat and subcutaneous fat levels), and movement during in-magnet exercise protocols. There are several approaches to calculating SNR of magnetic resonance spectra. Some approaches account for differences in magnetic resonance signal acquisition parameters (acquired flip angle, T1 and T2* relaxation rate, and partial saturations) (31). The approach used in this study is a rather simple method for calculating in vivo SNR that is easy to perform and similar to previous studies (2, 7, 40).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a calculation of SNR for NIRS measurements of mV̇o2. The SNR of NIRS data are likely influenced by ATT, NIR light intensity (gain settings on most commercially available devices), source-detector distances, and possible movement artifact during testing. Participants in this study underwent familiarization of both NIRS and 31P-MRS testing protocols before data collection to ensure the best possible data quality was collected. It is difficult to make direct comparisons of SNR between NIRS and 31P-MRS, but using the approach describe herein should allow for interlaboratory comparisons of data quality for both methodologies.

We utilized two approaches to analyzing 31P-MRS spectra: the peak heights and AMARES fitting routine. A direct comparison between analysis approaches showed a significantly better quality of curve fit for recovery kinetics of PCr and lower variation in the [PCr] in the resting scans using the peak heights analysis. The peak height analysis uses only the peak of the spectrum, which has the highest SNR of any point in the spectrum. After zero filling our spectra several times, we can accurately obtain the highest point. For a single resonance like PCr (in skeletal muscle), the peak height accurately reflects relative changes in peak area, assuming no overlapping peaks or changes in line shape (FWHM). Peak fitting algorithms like AMARES have advantages for analyzing MRS data that have complex and/or changing peak shapes, but requires extreme accuracy in phasing of the data. While the peak heights approach was superior to AMARES for the recovery kinetics, absolute concentrations (as done with our summed resting spectra) should be performed using a peak-fitting approach like AMARES.

Limitations and Assumptions

The participants in this study were all young, healthy, and relatively lean. It remains to be seen if the same level of agreement between NIRS and 31P-MRS would be found in other clinical populations. In participants with less well-coupled mitochondrial respiration (i.e., P/O ratio), the level of agreement between NIRS and 31P-MRS may be different. In this study, a continuous-wave NIRS device was used. These devices are unable to calculate the path length of NIR light, and therefore absolute calculations of O2 consumption are not possible. Instead, we chose to scale values to the maximal “physiological” calibration (ischemic calibration), as previously described (33), to allow for comparisons between individuals with varying amounts of adipose and skin tissues overlying the muscle of interest. While time-domain or frequency-domain devices can measure the path length and better estimate absolute values, this additional information will not influence the calculation of the rate constant (k) for the recovery of mV̇o2.

Perspectives and Significance

The present study provides conclusive evidence in support of a novel approach to measuring in vivo skeletal mitochondrial oxidative capacity using NIRS. The simplicity of this approach is highlighted by the use of short-duration voluntary exercise, followed by a series of short arterial occlusions, which could easily be performed in a variety of settings and participant populations. It should also be noted that NIRS has significant financial advantages over other methodologies like MRS. NIRS devices are commercially available for as little as $10,000, compared with several million dollars for a multinuclear magnet (plus operating and maintenance costs). The physiological importance of mitochondria is widely appreciated, and dysfunctional mitochondrial energetics have been associated with a number of health problems ranging from neuromuscular diseases and cancer to metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance. The NIRS approach described herein should be seen as an emerging technique with tremendous potential for expanding both our ability to study in vivo mitochondrial energetics and our understanding of the role of mitochondrial function in (patho) physiology.

GRANTS

This study was funded in part by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD-039676.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.E.R. and K.K.M. conception and design of research; T.E.R., W.M.S., and M.A.R. performed experiments; T.E.R. and W.M.S. analyzed data; T.E.R., W.M.S., M.A.R., and K.K.M. interpreted results of experiments; T.E.R. prepared figures; T.E.R. drafted manuscript; T.E.R., W.M.S., M.A.R., and K.K.M. edited and revised manuscript; T.E.R., W.M.S., M.A.R., and K.K.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Jared Brizendine and Michael Smith for assistance with data collection during this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1: 307–310, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boska MD, Hubesch B, Meyerhoff DJ, Twieg DB, Karczmar GS, Matson GB, Weiner MW. Comparison of 31P MRS 1H MRI at 1.5 and 2.0 T. Magn Reson Med 13: 228–238, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brizendine JT, Ryan TE, Larson RD, McCully KK. Skeletal muscle metabolism in endurance athletes with near-infrared spectroscopy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45: 869–875, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chance B, Im J, Nioka S, Kushmerick M. Skeletal muscle energetics with PNMR: personal views and historic perspectives. NMR Biomed 19: 904–926, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chance B, Williams GR. Respiratory enzymes in oxidative phosphorylation. IV. The respiratory chain. J Biol Chem 217: 429–438, 1955 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conley KE, Jubrias SA, Esselman PC. Oxidative capacity and ageing in human muscle. J Physiol 526: 203–210, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drost DJ, Riddle WR, Clarke GD, Group AMT. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the brain: report of AAPM MR Task Group #9. Med Phys 29: 2177–2197, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erickson ML, Ryan TE, Young HJ, McCully KK. Near-infrared assessments of skeletal muscle oxidative capacity in persons with spinal cord injury. Eur J Appl Physiol 113: 2275–2283, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes SC, Paganini AT, Slade JM, Towse TF, Meyer RA. Phosphocreatine recovery kinetics following low- and high-intensity exercise in human triceps surae and rat posterior hindlimb muscles. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R161–R170, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gnaiger E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 41: 1837–1845, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gollnick PD, Armstrong RB, Saltin B, Saubert CWT, Sembrowich WL, Shepherd RE. Effect of training on enzyme activity and fiber composition of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 34: 107–111, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamaoka T, Iwane H, Shimomitsu T, Katsumura T, Murase N, Nishio S, Osada T, Kurosawa Y, Chance B. Noninvasive measures of oxidative metabolism on working human muscles by near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol 81: 1410–1417, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanada A, Okita K, Yonezawa K, Ohtsubo M, Kohya T, Murakami T, Nishijima H, Tamura M, Kitabatake A. Dissociation between muscle metabolism and oxygen kinetics during recovery from exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart 83: 161–166, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holloszy JO. Biochemical adaptations in muscle. Effects of exercise on mitochondrial oxygen uptake and respiratory enzyme activity in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 242: 2278–2282, 1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holloszy JO, Oscai LB, Don IJ, Mole PA. Mitochondrial citric acid cycle and related enzymes: adaptive response to exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 40: 1368–1373, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph AM, Joanisse DR, Baillot RG, Hood DA. Mitochondrial dysregulation in the pathogenesis of diabetes: potential for mitochondrial biogenesis-mediated interventions. Exp Diabetes Res 2012: 642038, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kent-Braun JA, Sharma KR, Miller RG, Weiner MW. Postexercise phosphocreatine resynthesis is slowed in multiple sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 17: 835–841, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanza IR, Bhagra S, Nair KS, Port JD. Measurement of human skeletal muscle oxidative capacity by 31P-MR spectroscopy: a cross-validation with in vitro measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging 34: 1143–1150, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson-Meyer DE, Newcomer BR, Hunter GR, Joanisse DR, Weinsier RL, Bamman MM. Relation between in vivo and in vitro measurements of skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism. Muscle Nerve 24: 1665–1676, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lodi R, Taylor DJ, Schapira AH. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Friedreich's ataxia. Biol Signals Recept 10: 263–270, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCully KK, Fielding RA, Evans WJ, Leigh JS, Jr, Posner JD. Relationships between in vivo and in vitro measurements of metabolism in young and old human calf muscles. J Appl Physiol 75: 813–819, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCully KK, Forciea MA, Hack LM, Donlon E, Wheatley RW, Oatis CA, Goldberg T, Chance B. Muscle metabolism in older subjects using 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 69: 576–580, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCully KK, Iotti S, Kendrick K, Wang Z, Posner JD, Leigh J, Jr, Chance B. Simultaneous in vivo measurements of O2Hb saturation and PCr kinetics after exercise in normal humans. J Appl Physiol 77: 5–10, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCully KK, Mulcahy TK, Ryan TE, Zhao Q. Skeletal muscle metabolism in individuals with spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol 111: 143–148, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell P. Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature 191: 144–148, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motobe M, Murase N, Osada T, Homma T, Ueda C, Nagasawa T, Kitahara A, Ichimura S, Kurosawa Y, Katsumura T, Hoshika A, Hamaoka T. Noninvasive monitoring of deterioration in skeletal muscle function with forearm cast immobilization and the prevention of deterioration. Dyn Med 3: 2, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagasawa T, Hamaoka T, Sako T, Murakami M, Kime R, Homma T, Ueda C, Ichimura S, Katsumura T. A practical indicator of muscle oxidative capacity determined by recovery of muscle O2 consumption using NIR spectroscopy. Eur J Sport Sci 3: 1–10, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naressi A, Couturier C, Devos JM, Janssen M, Mangeat C, de Beer R, Graveron-Demilly D. Java-based graphical user interface for the MRUI quantitation package. MAGMA 12: 141–152, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paganini AT, Foley JM, Meyer RA. Linear dependence of muscle phosphocreatine kinetics on oxidative capacity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C501–C510, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 350: 664–671, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao H, Zhang X, Zhu XH, Du F, Chen W. In vivo 31P MRS of human brain at high/ultrahigh fields: a quantitative comparison of NMR detection sensitivity and spectral resolution between 4 T and 7 T. Magn Reson Imaging 24: 1281–1286, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan TE, Brizendine JT, McCully KK. A comparison of exercise type and intensity on the noninvasive assessment of skeletal muscle mitochondrial function using near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol 114: 230–237, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan TE, Erickson ML, Brizendine JT, Young HJ, McCully KK. Noninvasive evaluation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial capacity with near-infrared spectroscopy: correcting for blood volume changes. J Appl Physiol 113: 175–183, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan TE, Southern WM, Reynolds MA, McCully KK. Activity-induced changes in skeletal muscle metabolism with optical spectroscopy. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829a726a In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sako T, Hamaoka T, Higuchi H, Kurosawa Y, Katsumura T. Validity of NIR spectroscopy for quantitatively measuring muscle oxidative metabolic rate in exercise. J Appl Physiol 90: 338–344, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Beekvelt MC, van Engelen BG, Wevers RA, Colier WN. In vivo quantitative near-infrared spectroscopy in skeletal muscle during incremental isometric handgrip exercise. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 22: 210–217, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanhamme L, van den Boogaart A, Van Huffel S. Improved method for accurate and efficient quantification of MRS data with use of prior knowledge. J Magn Reson 129: 35–43, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vorgerd M, Schols L, Hardt C, Ristow M, Epplen JT, Zange J. Mitochondrial impairment of human muscle in Friedreich ataxia in vivo. Neuromuscul Disord 10: 430–435, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walter G, Vandenborne K, McCully KK, Leigh JS. Noninvasive measurement of phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in single human muscles. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 272: C525–C534, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wylezinska M, Cobbold JF, Fitzpatrick J, McPhail MJ, Crossey MM, Thomas HC, Hajnal JV, Vennart W, Cox IJ, Taylor-Robinson SD. A comparison of single-voxel clinical in vivo hepatic 31P MR spectra acquired at 15 and 30 Tesla in health and diseased states. NMR Biomed 24: 231–237, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]