Abstract

Although major advances have been made in delaying or preventing progression for the relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), little progress has been made to date in disease management for primary progressive MS (PPMS). Treatment strategies are largely focused on managing the symptoms of the disease and providing counseling and other forms of psychosocial support. The nurse plays a major role in managing these patients. This article summarizes a collaborative effort by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America to analyze the needs of this patient population and respond with programs that will meet those needs. This approach to developing a needs assessment is broadly applicable to other patient populations.

Multiple sclerosis (MS), the leading cause of disability in young adults,1,2 is a chronic, inflammatory disease of unknown etiology. It is hypothesized to be an autoimmune disease in which one or more environmental triggers act in a genetically susceptible individual.3–5 Central myelin and the oligodendrocytes that form central myelin appear to be the primary targets of the inflammatory attack, although the axons themselves are also damaged. MS may affect almost any part of the central nervous system (CNS) white matter (and gray matter to a more limited extent), resulting in a broad spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms.3 The diagnosis of MS is a clinical one, requiring evidence from the medical history, neurologic examination, and supporting laboratory findings, if needed, of multiple lesions that have occurred in different locations in the CNS and at different points in time (dissemination in space and time).6

Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years, although MS can occur in young children and older adults. Women are at least two to three times more likely to develop MS than men. The disease can occur in any racial group but is more common in whites of northern European ancestry.4

Four disease courses have been identified in MS7: 1) Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), the most common type, is diagnosed in approximately 85% of patients. It is characterized by periodic acute exacerbations of disease activity (relapses), which are primarily inflammatory in nature, and remissions, during which symptoms completely or partially remit.8 2) With time, most—but not all—people with RRMS transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS), a disease course characterized by disability progression, with or without any relapses. In this more progressive course, the disease process appears to be more neurodegenerative than inflammatory.9 3) Approximately 10% to 15% of people with MS experience a primary progressive disease course (PPMS). Unlike those with SPMS, individuals with PPMS experience disease progression from onset, without a preceding relapsing-remitting phase or subsequent relapses.7 4) Approximately 5% of patients experience steady progression from onset, but also have occasional relapses along the way; these patients have progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS). For the purposes of this article, this small group is considered a subset of those with PPMS.7

The Unique Characteristics of PPMS

Over the past decades, a variety of criteria have been used to indicate the diagnosis of MS, beginning with the Schumacher criteria,10 which relied primarily on the results of a neurologic examination to show evidence of demyelinating lesions in the CNS. The diagnosis of MS became much more straightforward with the advent of modern imaging techniques that make it possible to visualize CNS lesions, as well as a variety of laboratory tests for measuring immune reactions in the CNS. In 1983, the Poser criteria were proposed, which combined clinical findings with imaging and other test results.11 In 2001, the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis proposed what became known as the McDonald criteria.12 These have been updated and refined,13–15 most recently in 2010.16

Despite these significant advances, identifying those individuals who have the progressive forms of MS remains a challenge, especially early in the disease process. The diagnosis of PPMS is often made retrospectively, once a patient has exhibited steady progression without relapses over a period of years. There is a strong need to refine the definition of PPMS. This is not merely an academic issue: the lack of definition and the ability to use it to better characterize the processes involved in this form of the disease hampers the development of effective treatments.

Clinicians and researchers are seeking markers of disease that will allow for an earlier diagnosis and lead to improved therapeutic management. Although a number of factors have been identified as being more or less common in PPMS, to date no single factor has been identified as a diagnostic marker. Several definable characteristics predict progression17–20:

Clinically, PPMS is often characterized by an early, rapid progression, and those with three or more systems affected at the time of diagnosis may experience a more rapid progression.

The median age at diagnosis for patients with PPMS is about 10 years older than for those with RRMS. As a result, concomitant illness and incidental pathologies are more common.

Individuals with PPMS have a distinctive pattern of lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), including lesions in specific areas of the brain affected and a lower incidence of inflammatory lesions as compared with RRMS and SPMS. This is in keeping with the fact that inflammatory processes appear to play a lesser role in this type of MS.18 However, the distribution of lesions does not completely explain the pattern of symptoms seen in a given individual.

Brain and spinal cord atrophy, especially of gray matter, can be seen early in the course of the disease and helps predict disability. Atrophy is reflected by an increased ventricular volume, a decreased central cord area, and a decreased upper cervical cord area.

The most common symptoms of PPMS include mobility issues, progressive weakness, spasticity, pain, depression, cognitive changes, constipation, bladder dysfunction, respiratory complications, skin breakdown, osteoporosis and fractures, and dysphagia. These are not unique to the progressive forms of MS, but they tend to be persistent and especially difficult to manage.

Disease-Management Strategies in MS

Beginning in the early 1990s, a number of disease-modifying agents (DMAs) became available to treat the relapsing forms of the disease. In addition to reducing the frequency and severity of relapses, these medications have slowed the transition to SPMS for many individuals. However, none of the current DMAs, which primarily target the inflammatory process in MS, have shown benefit for people with PPMS, whose disease takes a progressive, neurodegenerative course from onset.21 These patients have remained what they often self-describe as an “orphan” population, with little or no prospect for relief from the steadily progressive course of the disease. Efforts to identify effective DMAs for PPMS are challenged by the difficulty of doing clinical trials in this population—largely due to the long time course of the disease and the lack of easily measurable changes, such as a decline in relapse rate. Clearly, there is a need to obtain more information specific to this form of MS.22

With no approved DMAs to offer, people with PPMS are often told that little can be done for them. Even though this form of MS is associated with the most severe and unrelenting symptoms, people with PPMS live without much hope of a “cure,” believing (correctly) that current research focuses primarily on the relapsing forms of the disease.

Rationale for the Current Project

People with PPMS have a wide range of needs. In addition to pharmacologic and other types of symptom management, they need ongoing supportive care from nurses, physicians, occupational (OTs) and physical therapists (PTs), and other specialists to address the physical and emotional issues that they experience while living with a steadily progressive and debilitating disease.

Realizing that this segment of the MS population is an underserved group, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) and the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America (MSAA) undertook a major analysis of the available data on this group and their support needs, with the goal of developing programs to meet these needs. This model, involving quantitative and qualitative data as well as expert opinion, can be replicated in other patient populations for which a needs assessment would lead to improvement in quality of life and care for the designated group, and where the necessary data are available or can be developed.

Methodology and Data Collection

A conference jointly sponsored by the NMSS and the MSAA, and funded by an educational grant from Genentech, was held in February 2008. Neither the grant from Genentech nor Genentech itself influenced the design, analysis, or presentation of the results, nor did it create any conflict of interest for the authors. The objective of the conference was to review the data derived from three MS databases and five focus groups, and to use the information as a basis for addressing the unmet needs of this underserved community, as well as the concerns of health-care providers. Participants at the conference included MS specialist clinicians, people with PPMS and their support partners, data analysts, and staff from both organizations.

Database Analysis

Information on the PPMS segment of the MS population from three self-report databases was analyzed.

Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study

The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study, sponsored by the NMSS since 1999, follows a population-based cohort of approximately 2000 people with MS in order to evaluate a variety of factors, including demographic and clinical characteristics,23 use of MS specialists and DMAs,24,25 and quality of life.26 The Slifka sample, which was drawn from all regions of the United States, employed random sampling techniques and included people who do not use traditional health services as well as people who live in nursing facilities. As a result, with the application of sampling weights that management account for the probability of selection and adjust for nonresponse, the sample can be used to produce population-based estimates for a number of variables.

MSAA 2005–2006 Comprehensive Client Needs Assessment

The MSAA's 2005–2006 Comprehensive Client Needs Assessment was sent to all 2058 of the association's members. Responses were received from 762 members, 76 of whom had PPMS. Respondents, including people with MS and care partners, were asked a variety of questions regarding demographics, medical history, and disease characteristics, as well as questions about their information and service needs (S. S. Cofield, PhD, oral communication, February 7, 2008).

North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis Patient Registry

The North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Patient Registry is a project of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC).27 Individuals with MS are invited to enroll in the Registry through direct mailings, MS centers, support groups, and the Registry's website. Upon enrollment, registrants complete a detailed questionnaire, and they have the option to update their core data biannually. Data for this PPMS project were obtained from the 3567 people with MS in the study who self-identified as having this disease course (S. S. Cofield, PhD, oral communication, February 7, 2008).

Online Focus Groups

The NMSS and the MSAA commissioned Mindspot Research, an Orlando, Florida–based company that specializes in the conduct of online, in-person, and telephone consumer focus groups, to conduct qualitative research to explore issues that different stakeholder groups face in living with, managing, and treating PPMS. A series of five online focus groups helped guide the development of strategic planning and programs to address the needs of people with PPMS. Two groups included both adults with a diagnosis of PPMS and family members/care partners. The patients included an even mix of men and women from 14 states, predominantly white and in the age range of 35 to 61 years. All had been diagnosed with PPMS at least 4 years previously. The third group was made up of MS specialist neurologists, the fourth of MS nurses, and the fifth of psychologists and licensed social workers who treat people with MS. Each of the groups lasted 60 to 90 minutes and occurred during the period January 15 to 17, 2008.

Results

The Demographics of PPMS

Information on the following demographic factors was consistent among the three databases:

The percentage of people with MS who have the primary progressive form is approximately 10%; approximately 5% have the progressive-relapsing form.

People with PPMS tend to be older at age of onset of symptoms than those with RRMS. They also tend to be older as a group than those with RRMS.

A higher proportion of men are affected by PPMS—approximately 50% as compared with the 25% to 35% in most studies of the general MS population. The PPMS group also has a higher number of men with advanced levels of disability.

People with PPMS tend to be more disabled than those with RRMS or SPMS. In the MSAA Needs Assessment, this was reflected by a lower percentage of the population living independently (83% for PPMS vs. 92% for RRMS and 93% for SPMS) and a higher percentage having a care partner (73% vs. 58% for RRMS and 57% for SPMS). Additionally, 43% of those with PPMS were unable to walk, compared with 5% of people with RRMS and 28% of those with SPMS. People with PPMS are much more likely to need help with activities of daily living (ADLs) than those with RRMS, and they require more assistance in the home.

People with PPMS are less likely to be working than those with RRMS, and they have lower family incomes. They are much more likely to receive Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) benefits than are those with RRMS (67% vs. 41%), and are somewhat more likely to be on SSDI assistance than are those with SPMS (67% vs. 62%).

The Self-Identified Needs of People with PPMS

Patient needs are intertwined. The onset of new symptoms—or the worsening of existing ones—has serious consequences for many nonmedical areas, ranging from interpersonal and family relationships to economic issues such as employment and insurance coverage. Conversely, improvements in symptom control or psychosocial support can contribute to general well-being as well as to improving relationships and practical issues such as the ability to continue working.

From the MSAA's Needs Assessment, the NARCOMS database, and the five focus groups, a number of broad areas were identified as being in need of improvement, including education, medical management, insurance coverage, the management of mental health and emotional issues, quality of life needs, family and caregiver support, and support for health-care providers.

The Need for Targeted Information

A theme flowing through all focus groups and the conference was the need for better dissemination of information about PPMS, including the treatment strategies and support services available to help manage it.

The NMSS and MSAA play a broad role in providing information about MS, and both organizations are viewed as key resources. Some patients and family members take active advantage of these educational resources while others do not.

In the focus groups, a clear discrepancy existed between patient/family reports and those of physicians concerning utilization of these organizations. Patients and families indicated that, for the most part, their health-care professionals did not refer them to these organizations at the time of diagnosis or later; however, physicians reported much higher levels of referral than the patients indicated. This is not unusual; a substantial discrepancy exists across a range of diseases between reports from patients and physicians concerning what information was offered at the time of diagnosis.28–30

Medical Needs

Feedback from the five focus groups confirms that, in many ways, the management of PPMS today is similar to that of MS in general before the first DMAs became available in the early 1990s. Because no medications have been found to slow or halt progression of PPMS, symptom management, rehabilitation, and psychosocial support remain the major focus of treatment. Physical and occupational therapy and other types of intervention are extremely helpful but often difficult to obtain because of insurance and related financial issues.

The primary medical needs of people with PPMS— expressed in the patient focus groups and confirmed in the professional focus groups—include research targeting the causes and cure, as well as ways to decrease disability progression; strategies to enhance overall health care; ways to improve access to home health care; and more time and better communication with physicians and other health-care providers, such as nurse practitioners.

Psychological Changes and Challenges

Mood. Information from the Sonya Slifka Study and the five focus groups provided important information about mood-related issues: People with MS—regardless of their disease course—are at greater risk for severe depression than people in the general population or with other chronic illnesses.31 Approximately 50% of people with MS will experience a major depressive episode at some point in the disease.31,32

However, the five focus groups were consistent in reporting that there is a significant attitudinal difference. People with the relapsing forms of MS, for which effective DMAs are available, live with constant anxiety about new attacks, which usually come without warning. In contrast, people with the progressive forms tend to feel hopelessness and resignation based on the knowledge that no effective therapies exist or are expected to exist in the near future. A similar theme—that people with PPMS have a significantly weaker belief in their ability to control their disease and function with it than do those with relapsing forms of the disease—has been confirmed in the literature.33

According to the group participants, many nonmedical issues contribute to the emotional stresses of PPMS, including financial pressure and stress, long-term planning needs, and a loss of the ability to work; neglect and other quality of life issues; a loss of independence and being dependent on family members for assistance; family and relationship stress, marital problems, and intimacy issues; caregiver burden and burnout; and a general fear of the future.

In the focus groups, people with PPMS reported being “scared and confused” when they received their MS diagnosis and again when they were told they had PPMS. Despite this, it is rare for a social worker or other mental health professional who could provide emotional support to be present at the time of the diagnosis with MS, including PPMS. Rather than recommending a counselor, neurologists may suggest that their newly diagnosed patients contact the NMSS or MSAA to learn about available services, as they tend to believe that the first thing patients need is information about MS or PPMS. They may recommend counseling if it is evident that the patient is experiencing difficulty in dealing with the diagnosis. In the worst-case scenario, no referral is made at all.

Negative connotations associated with mental health issues may cause some people to avoid seeking help from a mental health professional. This may be addressed by the way in which material is offered—for example, information might be better received if it is presented as “education” or “counseling” rather than “therapy.” This is an often-neglected area, in large part because of the tendency to prioritize physical symptom management over emotional and social issues. In addition, access to mental health services is often restricted as a result of financial and insurance challenges.

Cognition. The five focus groups identified cognitive changes as another significant challenge in PPMS. In MS overall, between 50% and 66% of people experience some degree of cognitive dysfunction, with the primary deficits occurring in the areas of learning and memory, attention and concentration, information processing speed, and executive functions including problem-solving, organization, and decision-making.34 Cognitive changes can interfere with daily functioning, adherence to treatment, self-care, planning and problem-solving, and interpersonal relationships.35

Quality of Life Needs

The most common symptoms experienced by people with PPMS have a tremendous effect on social patterns with friends and families. A “quality of life needs ladder” emerged from the discussions of the five focus groups, beginning with independence and normalcy at the top, and continuing down through dignity, socialization, cognition, and mental health. People with PPMS reported that they tend to move down this ladder as their physical condition deteriorates.

The members of the patient focus groups viewed a “good day” with MS as one in which they generally were not experiencing major symptoms, felt energized, were without pain or stress, were able to think clearly, and could participate in normal activities and enjoy simply being alive and loved. On a “bad day,” they focused more on symptoms—including fatigue, weakness, stress, depression, medication issues, and bowel and bladder problems. They experienced a lack of human contact and felt they had nothing to look forward to.

When asked what concerned them the most, patient responses focused on what the future would bring, how the disease would affect their relationships, worries about becoming a physical and financial burden on their families, financial issues—including the cost of care—and a general fear of the unknown.

Family and Caregiver Challenges

Family members and caregivers shared their feelings about being overwhelmed or burned out by the demands of the assistance they are providing and the multiple roles they are forced to take on in the household—experiences that are confirmed in the MS caregiver literature.36,37 Care partners in the focus groups expressed the need for assistance with home care and respite care as well as less isolation and more balance in their lives.

Compounding the pressure on caregivers is the feeling of guilt they often experience about doing something for themselves. They seem to need “permission” to take care of themselves and take advantage of available programs and resources, such as the well-spouse programs sponsored by the National Association of Home Care (NAHC). As in most other areas, information about existing resources for partners has not been readily available.

Conference Recommendations

The information derived from the databases and focus groups has broad implications for the provision of support services to people with PPMS and their families. The lack of effective therapies and the extent of advanced disease make it critical to provide effective symptom management. Information is needed about a wide range of nonmedical issues, including employment (how to maintain it as long as possible, and leave the workforce when the time is right), financial planning, transportation options, assistive technology, social isolation, changing family roles, and loss of intimacy. And individuals with PPMS and their families need assistance in obtaining financial aid for all the services for which they tend to be underinsured38—assistive equipment, home care, adult day health programs, and nursing home care—as well as accessible housing options.

This section summarizes the recommendations made by the conference attendees in response to identified needs. The recommendations were made with the caveat that any new programs and strategies must be accompanied by research that can provide quantifiable measures of efficacy.

Information for All

Members of the PPMS task force recommended that more printed and online materials be developed for this population, including information that can be given out at the time of diagnosis. This suggestion is now being implemented by both organizations. Specific products include the following:

A separate website for PPMS, or one that is clearly and easily accessible from within the major MS organization sites.

A book on PPMS to provide all needed information and resources in a single, easy-to-use form. This book has recently been published and is available at no charge from the NMSS and the MSAA for people affected by PPMS.39

A printed newsletter publication, to be available online or by e-mail, covering all aspects of PPMS and providing resources for everyone affected by it.

Continuing education for health professionals as well as print and online publications.

Medical Care

People with PPMS need access to high-quality comprehensive health care provided by knowledgeable professionals. As with other chronic illnesses and disorders, the management of PPMS is best provided by a comprehensive approach that focuses on their symptoms and quality of life. This involves a move away from the “medical” model of care toward a “functional” model in which the concerns of patients, family members, and caregivers play a key role, with services provided by a wide variety of health-care professionals.

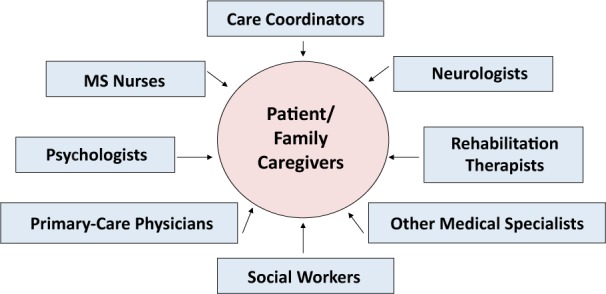

The MS specialist team should include physicians, nurses, OTs and PTs, psychologists and psychiatrists, social workers, speech and language pathologists, and others as needed (Figure 1). Nurses play a key role in ensuring optimal delivery of care, often serving as the “point person” and coordinator for the person with MS.

Figure 1.

Patient-centered and seamless integrated medical and functional model of care

The availability of rehabilitation and personal care services is of critical importance to the person with MS. The ever-changing course of the disease affects patients in many ways. Services that will help maximize capacity and quality of life must be available and affordable. Services such as physical and occupational therapy and personal care are often financially restricted by insurance companies and government programs. These services are often time-limited and tied to hospitalizations, and have lifetime usage limits. These restrictions are inappropriate for a chronic disease such as MS. Strategies, including legislative and policy advocacy, must be developed and implemented to make these services more broadly available.

Services and Resources

Even when services are available, people with MS and their families often fail to take advantage of them, in part because they do not know how or where to begin. To address this issue, it is essential that anyone affected by MS be able to “navigate” the system to find the extensive resources and support that are available. The clinic nurse has a key role to play in helping patients and their families access available information and services.

MS Navigator

The NMSS's MS Navigator program was recently developed to ensure that those who call the society are easily connected to the wide variety of available services. Staff members can help clients identify financial planning resources or emergency financial assistance, home health-care providers, and transportation and other resources; inform people of clinical trial opportunities; reduce nonreimbursed care through prolonging employment, increasing insurance coverage, and other resources; and address quality of life issues.

Service is provided at three levels: The entry-level tier provides information and referrals. It helps people with MS reach the professionals who can help them with specific problems and directs them to available resources. The second tier is services management. In this tier, staff members provide service that goes beyond information and referral; this may involve more extensive knowledge of community resources and of the processes required to obtain needed services. Staff members work individually with people to fill out forms, contact community agencies, or coordinate between agencies. This type of service usually takes more time and may involve multiple contacts with the individual. The third tier is care coordination/management. Most NMSS chapters provide some level of care management. Typically, the chapter contracts with an external care management company to provide an in-depth assessment and targeted care interventions. Some chapters have internal care management staff and programs. Traditionally, fewer people participate in this level of service. Services can include home safety assessments, physical or occupational therapy following acute attacks or change in symptoms, developing plans and contacting community services to help maintain independence, or transitions to assistive-care facilities.

Helpline

The Association provides consultation, information, and referral through its Helpline. This service is enhanced by a comprehensive resource database that allows quick access to program and service information across the nation. The information in this system is provided and continuously updated by volunteer Resource Detectives, many of whom have been directly affected by MS.

Emotional Support

People with PPMS need better ways to broaden their support circle to include others who have this form of MS. A recurring theme among patients and care partners was that they need support groups that are specifically targeted to their needs rather than to those of the general MS population.

The Internet is a good way to provide online support for people affected by PPMS—utilizing chat rooms, bulletin boards, and social media sites such as Facebook.

Self-help group leaders could offer telephone support to people with PPMS. Training people with PPMS to become support group leaders and provide telephone support to others would expand the number of people available for this activity.

MyMSMyWay.com, a collaborative project involving the NMSS, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, and Microsoft, has been developed to help interested people with MS utilize accessible technology to increase their productivity and social interactions.

Family/Care Partner Issues

To address the needs of family members and care partners, the following suggestions were made:

Wellness programs for care partners could include exercise, stress management, and information about nutrition, as well as programs to make sure that caregivers receive regular medical care. Information about existing programs such as the NMSS's Gateway to Wellness and collaborative programs with Can Do Multiple Sclerosis (CanDoMS.org) are available through chapters, and might be adapted for care partners.

Classes on caregiving essentials, especially if given in the home, could include such topics as safe transfers, feeding, bathing, transportation, how to pick up a person who falls, and transportation options. A text on this topic, co-sponsored by the NMSS, is already available.40 Issues such as legal and financial planning would also be appropriate.

The Share the Care model41 could be applied to MS. It uses volunteer care coordinators to bring in family, friends, church groups, and others who can help with care needs and provide respite for caregivers.

Support groups specifically for caregivers of people with PPMS, or one including those whose partners have SPMS and similar illnesses, would be very helpful, as their issues differ from those of caregivers of people with relapsing forms of MS. Because many caregivers have difficulty leaving the home for an extended period, an online or telephone support group might be especially useful.

Respite grants could be given directly to caregivers; their nature could be widely variable and defined by individual caregivers.

Health-Care Providers

The members of the professional focus groups felt strongly that health professionals need information and training specific to PPMS:

Continuing education conferences at the regional and local levels, with accompanying written and visual materials, should be developed for people in all disciplines involved in the management of MS. These materials will allow providers to learn about progressive MS and to create an opportunity for networking to facilitate the sharing of knowledge. Goals for these programs should include teaching physicians how to implement integrated care, and providing all health-care professionals with information on maximizing reimbursement for services.

Clinicians need to remember that “it is not always MS.” People with PPMS also need ongoing general medical care, including access to regular health screenings and other wellness strategies.

Preceptorships and other types of mentoring opportunities should be developed. A 5-day prototype training session for physicians and nurses at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center could be expanded if adequate financial support were available.

MS organizations and centers should partner with community agencies, rehabilitation clinics, and other organizations that have shown a commitment to MS.

Student internships and fellowships could be developed in partnership with local universities.

Funding for these programs could come from a variety of sources: the National Institutes of Health (NIH), private foundations, state agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and partnerships with universities.

Summary

Primary progressive MS affects 10% to 15% of all people with MS and is associated with severe and unrelenting symptoms. Treatment of this type of MS has lagged in comparison with the dramatic advances that have been made in treating the relapsing-remitting forms of MS. The NMSS and MSAA have analyzed the needs of this patient population and are initiating programs to meet those needs. These include a wide range of medical and nonmedical issues. Care must be provided in a comprehensive, interdisciplinary fashion, and the nurse plays a key role in ensuring continuity of care. The approach described in this article to developing a needs assessment is applicable to a broad range of patient populations.

PracticePoints.

Primary progressive MS (PPMS) affects 10% to 15% of all people with MS and is associated with severe and unrelenting symptoms.

Treatment of PPMS has lagged in comparison with the options available for treating relapsing forms of MS.

Care must be provided in a comprehensive, interdisciplinary fashion, with the nurse playing a key role in ensuring continuity of care, and MS advocacy groups providing programs to address the complex psychosocial challenges.

Online Resources for People with Progressive Forms of MS.

Agencies

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). www.cms.gov.

Department of Veterans Affairs. www.va.gov. The VA provides a wide range of benefits and services to those who have served in the armed services, their dependents, beneficiaries of deceased veterans, and dependent children of veterans with disabilities.

Medicare. www.medicare.com.

Medline Plus. www.medlineplus.gov. A service of the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health that provides health news, drug information, clinical trials listings, and links to other databases.

National Health Information Center. www.health.gov/nhic. Maintains a database of health-related organizations.

National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. www.loc.gov/nls.

President's Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities. www.usccr.gov/pubs/crd/federal/pcepd.htm.

Social Security Administration. www.ssa.gov.

MS Organizations

Can Do Multiple Sclerosis (formerly the Heuga Center for Multiple Sclerosis). www.mscando.org. An innovative provider of lifestyle empowerment programs.

Centers for Independent Living. www.ncil.org. Network offering advice, training, and advocacy.

Multiple Sclerosis Association of America. Publications can be accessed at: www.msassociation.org/publications.

Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. www.msif.org. Links the activities of MS societies worldwide.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Information and resources related to PPMS can be accessed at: www.nationalMSsociety.org/PPMS.

The Well Spouse Association. www.wellspouse.org. An emotional support network for spousal caregivers.

Accessibility Resources

AbleData. www.abledata.com. Objective information about assistive-technology products and rehabilitation equipment.

Accessible Journeys. www.disabilitytravel.com. Arranges travel for people with disabilities.

National Rehabilitation Information Center (NARIC). www.naric.com. Access to resources for employment, advocacy, benefits and financial assistance, education, and technology.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: The conference from which this article stems was jointly sponsored by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Multiple Sclerosis Association of America and was funded by an educational grant from Genentech.

References

- 1.McDonald WI. Relapse, remission, and progression in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1486–1487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2006;332:525–527. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7540.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herndon R. Pathology and physiology. In: Burks J, Johnson K, editors. Multiple Sclerosis: Diagnosis, Medical Management, and Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2000. pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frohman EM. Multiple sclerosis. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:867–897. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyment DA, Ebers GC, Sadovnick AD. Genetics of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:104–110. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00663-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coyle P. Diagnosis and classification of inflammatory demyelinating disorders. In: Burks J, Johnson K, editors. Multiple Sclerosis: Diagnosis, Medical Management, and Rehabilitation. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2000. pp. 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:907–911. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heard RN. The spectrum of multiple sclerosis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:280–284. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tallantyre EC, Bø L, Al-Rawashdeh O, Polman CH, Lowe JS, Evangelou N. Clinico-pathological evidence that axonal loss underlies disability in progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:406–411. doi: 10.1177/1352458510364992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher GA, Beebe G, Kebler RF, et al. Problems of experimental trials of therapy in multiple sclerosis: report by the Panel on the Evaluation of Experimental Trials of Therapy in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1965;122:552–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb20235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poser C, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:227–231. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Seze J, Debouverie M, Waucquier N, et al. Diagnostic criteria for primary progressive multiple sclerosis: a position paper. Mult Scler. 2007;13:622–625. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson AJ, Montalban X, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnostic criteria for primary progressive multiple sclerosis: a position paper. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:831–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawker K. Prognosis and treatment for primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Paper presented at: 22nd Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 28–31, 2008; Denver, CO.

- 18.Pelletier D. Imaging of primary progressive MS. Paper presented at: 22nd Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 28–31, 2008; Denver, CO.

- 19.Racke MK. Immunopathology of PPMS. Paper presented at: 22nd Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 28–31, 2008; Denver, CO.

- 20.Wolinsky JS. PPMS: natural history and diagnosis. Paper presented at: 22nd Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 28–31, 2008; Denver, CO.

- 21.Samkoff L. Immunomodulatory agents for relapsing-remitting MS. In: Giesser BS, editor. Primer on Multiple Sclerosis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson A. Overview of primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS): similarities and differences from other forms of MS, diagnostic criteria, pros and cons of progressive diagnosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10(suppl 1):S2–S7. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1024oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Perloff J, Srinath KP, Hoaglin DC. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12:24–38. doi: 10.1191/135248506ms1262oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minden SL, Hoaglin DC, Hadden L, Frankel D, Robbins T, Perloff J. Access to and utilization of neurologists by people with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;70(13 pt 2):1141–1149. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306411.46934.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minden S, Hoaglin D, Jureidini S, et al. Disease-modifying agents in the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. Mult Scler. 2008;14:640–655. doi: 10.1177/1352458507086463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu N, Minden SL, Hoaglin D, Hadden L, Frankel D. Quality of life in people with multiple sclerosis: data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. J Health Hum Serv Admin. 2007;30:233–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flachenecker P, Stuke K. National MS registries. J Neurol. 2008;255(suppl 6):102–108. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-6019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dibbelt S, Schaidhammer M, Fleischer C, Greitemann B. Patient-doctor communication in rehabilitation: the relationship between perceived interaction quality and long-term treatment results. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch-Weser S, Dejong W, Rudd RE. Medical word use in clinical encounters. J Health Communication. 2009;15:590–602. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heeson C, Kolbeck J, Gold SM, et al. Delivering the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: results of a survey among patients and neurologists. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107:363–368. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minden SL, Orav J, Reich P. Depression in multiple sclerosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1987;9:426–434. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(87)90052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadovnick AD, Remick RA, Allen J, et al. Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:628–632. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraser C, Polito S. A comparative study of self-efficacy in men and women with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39:102–106. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeLuca J. What we know about cognitive changes. In: LaRocca N, Kalb R, editors. Multiple Sclerosis: Understanding the Cognitive Challenges. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2007. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaRocca N, Kalb R. Multiple Sclerosis: Understanding the Cognitive Challenges. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buhse M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40:25–31. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200802000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aronson KJ. Quality of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Neurology. 1997;48:74–80. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Hoaglin DC. Access to healthcare for people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:547–558. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holland NJ, Burks J, Schneider DM. Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. New York, NY: DiaMedica; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer MM, Derr P. Portland, OR: CareTrust; 2006. The Comfort of Home, Multiple Sclerosis Edition: An Illustrated Step-by-Step Guide for Multiple Sclerosis Caregivers. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Capossela C, Warnock S, Miller S. Share the Care: How to Organize a Group to Care for Someone Who Is Seriously Ill. Wichita, KS: Fireside; 2004. [Google Scholar]