Abstract

The objective of this study was to identify characteristics of informal caregivers, caregiving, and people with multiple sclerosis (MS) receiving this assistance that are associated with the strength of the care-giver/care recipient relationship. Data were collected in a national survey of informal caregivers and analyzed using an ordered logistic regression model to identify factors associated with caregiver perceptions of the strength of the relationship with the person with MS. The overall health of the person with MS was significantly associated with caregiver perceptions that providing assistance strengthened the caregiver/care recipient relationship, with poor health having a negative impact on the relationship. A spousal relationship between the caregiver and the person with MS was associated with significantly lower perceptions of a strengthened relationship. Conversely, caregiver perceptions that MS symptoms interfered with the independence of the person with MS in daily life were associated with caregiver perceptions of a strengthened relationship. Longer duration of caregiving and more hours per week spent providing assistance also were associated with a stronger relationship. In contrast, we found a significant negative association between caregiver perceptions that assisting the person with MS was burdensome and the strength of the relationship. Similarly, higher levels of education among caregivers tended to have a significantly negative impact on the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Our findings highlight the importance of addressing the needs and concerns of spousal caregivers. Health professionals who treat informal caregivers, as well as those treating people with MS, should be sensitive to the impact caregiving has on caregivers, especially spouses providing assistance.

About 30% of people with multiple sclerosis (MS) need supportive and maintenance assistance at home, with 80% of that care provided by informal or unpaid caregivers, usually family members.1,2 Informal caregivers enable people with MS to remain in their homes as their functional limitations become more permanent and their needs for personal assistance increase.3,4 These informal caregivers provide a variety of services, including personal care, homemaking, and assistance with daily activities, mobility, and leisure activities.5–8 Most previous studies of informal caregivers assisting people with MS focused on burden and stress. The objective of the present study was to develop preliminary analyses to identify factors associated with positive aspects of caregiving, focusing on caregiver perceptions that providing assistance has improved or strengthened the relationship with the person with MS. The study also aimed to identify aspects of informal caregiving that have a negative impact on the caregiver/care recipient relationship.

Caregiver Burden and MS Care

An earlier study found that more than 20% of informal caregivers assisting people with MS thought that this caregiving was burdensome either most or all of the time.9 Caregiver burden is a reaction to factors associated with providing assistance to the person with MS on a daily basis, including physical, psychological, emotional, and social stressors.10 Other studies found that emotional factors among caregivers and assisting more severely affected people with MS were major predictors of care-giver burden.11,12 Psychiatric symptoms and cognitive impairment in the person with MS have been linked to caregiver distress.13 Forbes et al.14 found that the impact of MS and patient and caregiver health explained most of the variance in burden among caregivers. Strategies that reduce burden are necessary to improve the health and quality of life among caregivers and people with MS receiving their assistance.12,15

Positive Aspects of Caregiving

Recent studies have focused on the benefits to informal caregivers from assisting a person with MS. Benefits derived from assisting a family member with MS can sustain the caregiver over the duration of caregiving.16 Benefit finding is the identification of benefits in adverse situations, helping the caregiver or the person with MS cope with this adversity.17–19 Caregivers assisting people with MS have reported a range of benefits from their caregiving, with more than one-third of MS caregivers reporting personal growth.18 Sense making, a related concept, is the development of explanations by caregivers or the person with MS for adversity.20,21 Pakenham22 identified six factors that describe sense-making explanations used by MS caregivers to explain their situation, including caregiving as a catalyst for change and an expression of close relationships.

Health-care practitioners should recognize the variety of benefit-finding and sense-making themes expressed by caregivers to facilitate efforts to discover gains in their experiences providing assistance to people with MS.16,18,20,22 Sharing positive and negative caregiving experiences in support groups also could promote benefit finding among caregivers.16 Our study builds on this benefit-finding research to identify characteristics of caregivers and the people with MS receiving care that are associated with caregiver perceptions that providing this assistance has improved or strengthened their relationship with the person with MS.

Methods

The data analyzed in this study were collected in a national survey of 530 people providing informal or unpaid care to people with MS who were more disabled and dependent. (However, 414 caregivers provided all data in their survey responses needed to implement our regression model.) We developed the sample of 530 informal caregivers by contacting people with MS participating in the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry who were more functionally dependent. The level of functional dependence was measured using the Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale, a self-assessment of the ability of the person with MS to walk, with scores ranging from 0 (normal) to 8 (bedridden).23 We included in the study only people with MS who needed a cane to walk 25 feet (score of 5), required bilateral support (score of 6), primarily used a wheelchair or scooter (score of 7), or were bedridden (score of 8). We identified 4943 NARCOMS Registry participants with MS who met our impairment criteria. Although our survey included only informal caregivers assisting people with MS who had greater disability and impairment, about 41% of responders to the NARCOMS update survey in Spring 2006 reported similar dependency levels.9

NARCOMS Registry

The NARCOMS Registry contains the names and contact information of more than 35,000 people with MS who volunteered to participate in routine data collection and possibly other research projects.24 It is estimated that up to 10% of Americans with MS are in the NARCOMS Registry.25 People with MS at least 18 years of age are invited to enroll in the Registry through direct mailings, MS clinical centers, support groups, and the NARCOMS Registry website.26 The enrollment process involves completing a NARCOMS questionnaire, which collects data on demographic characteristics, MS-related symptoms, disease-modifying and symptomatic therapies, and the use of various health services. Registry participants are assured confidentiality and that their names will never be disclosed to anyone without the participant's written permission.

Caregiver Interview Questionnaire

Our survey was designed to record the caregiver's perceptions of the impact of MS on the person receiving their assistance, the care needs of the person with MS, the informal care and services provided, and how assisting the person with MS affected the caregiver. We conducted two focus groups to help identify important issues and questions to include in the survey interview. The focus groups were conducted in Waltham, Massachusetts, during July 2004 and Springfield, Missouri, during August 2004. The Ozark Branch of the Mid America Chapter and Greater New England Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society assisted with the recruitment of focus group participants. In addition, the Lone Star Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society in Houston, Texas, recruited three volunteers during August 2006 to pretest the computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) program and the survey process and assess the clarity and acceptability of survey questions. This pretest was successful, with no major changes to the CATI process or questionnaire deemed necessary.

The 35-minute interview asked about the caregiver's relationship with the person with MS, MS disease and symptom characteristics, and demographic information about the person with MS and the caregiver. The interviewer asked the caregiver to assess the overall health status of the person with MS and the cognitive decision-making ability of the person with MS, with this cognitive-related question adapted from the “Minimum Data Set for Nursing Home Resident Assessment and Care Screening.”27 The interviewer read a list of statements assessing the caregiver's feelings and attitudes experienced when assisting the person with MS, such as “caregiving is burdensome.” These caregiver feelings were measured using a 5-point Likert item, with possible responses of none of the time, once in a while, some of the time, most of the time, and all of the time. The interviewer also asked the caregiver the average number of hours per week spent helping the person with MS cope with the effects of their illness. The caregiver was asked whether any unpaid caregiver was employed to help the person with MS perform activities of daily life.

The interview included the 8-item Short Form Health Status Survey (SF-8), which is designed to provide a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) profile.28,29 Previous studies have documented the validity of the SF-8 in the United States,29 and the SF-8 meets standard evaluation criteria for content, construct, and criterion-related validity.28 The SF-8 HRQOL profile consists of eight items and includes a Mental Component Summary (MCS), with higher scores indicating better health-related status. In our study the SF-8 measured the HRQOL of the caregiver, not the person with MS. The interviewer began the SF-8 segment of the survey by telling the caregiver, “I will now briefly ask your views about your overall health, about how you feel, and how well you are able to do your usual activities.” We included the MCS from the SF-8 in our analysis as a measure of the mental health status of the caregiver. Caregivers were asked to provide a self-assessment of their overall health using a question from the SF-8 interview.

The interviewer asked the caregiver to provide any number from 0 to 10 to describe how MS symptoms affected the independence of the care recipient in daily life, with 0 being no interference at all and 10 being the most severe interference. The caregiver was also asked to rate on a scale from 0 to 10 the extent to which assisting the person with MS “affects your ability to perform activities in daily life that are important to you,” with 0 indicating no negative impact at all and 10 indicating the most severe impact. The caregiver was also asked to rate on a scale from 0 to 10 their satisfaction with the access that the person with MS had to MS-focused care, with 0 indicating total dissatisfaction with access and 10 indicating complete satisfaction with access. MS-focused care integrates the expertise of many health professionals, including neurologists, nurses, urologists, rehabilitation specialists, physical and occupational therapists, and mental health specialists. The goal of MS-focused care is comprehensive, coordinated care designed to manage the disease and promote function, independence, health, and wellness.30 The scales developed for this study were adapted from the 0 to 10 scales used in the Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems (CAHPSR) survey.31

Survey Process

A recruitment letter was mailed to the 4943 Registry participants with MS who met our disability criteria, requesting their assistance to identify informal caregivers. These letters explained the purpose of the study, stating that we wanted to interview “the person who provides the majority of informal or unpaid care to you to help you cope with the effects of MS on your daily life.” This letter requested that the person with MS ask the person who provided the majority of their informal or unpaid care to call a toll-free telephone number to complete an interview. This CATI process was administered by the Public Policy Research Institute (PPRI) at Texas A&M University.

About 1000 recruitment letters per week were mailed during September 2006, for a total initial mailing of 4071 letters. By December 2006, we completed interviews with 432 informal caregivers. Additional recruitment letters were mailed in January 2007 to another 872 people with MS not included in the September 2006 mailings. When the survey process ended in March 2007, we had completed 530 interviews with informal caregivers to people with MS. The survey was stopped when no caregivers called in during a 2-week period. The pretest and survey process were approved by the Office of Regulatory Compliance at Mississippi State University (study design and data analysis) in June 2006 and by the Office of Research Compliance, Institutional Review Board, at Texas A&M University (interview administration) in July 2006.

Calculation of a participation rate for our survey is difficult because we do not know how many people with MS receiving our recruitment letter had an informal caregiver. It is estimated that about 30% of people with MS require some type of home care assistance, with 80% of that assistance provided by informal caregivers.1,2 Using those estimates, about 25% of people with MS have an informal caregiver, or about 1235 of the 4943 people with MS who received our recruitment letters. Given the study's focus on more functionally dependent people with MS, this estimate of 1235 informal caregivers may be low. Assuming 1235 informal caregivers, 530 completed interviews yields a 43% participation rate.

Ordered Logistic Regression Model

We developed an ordered logistic regression model using survey data to analyze the contributions of characteristics of the person with MS and the caregiver to caregiver perceptions that providing assistance improved or strengthened the caregiver/care recipient relationship. These analyses included 414 caregivers in the regression model (caregivers providing all data in their survey responses needed to implement our model). The dependent variable is the caregiver's assessment that assisting the person with MS improved or strengthened their relationship. The interviewers said to each caregiver, “I would like you to tell me how you feel about your caregiving experiences. Please tell me how the following phrases reflect your experiences or attitudes about providing care to [the person with MS].” The interviewers read the statement “caregiving has improved or strengthened our relationship,” with caregiver responses providing data for the dependent variable. Caregiver perception of the strength of the relationship was measured using a 5-point Likert item, with possible responses of none of the time, once in a while, some of the time, most of the time, and all of the time. This Likert scale has face validity. In addition, we pretested the interview questionnaire before we began the full-scale survey, with no problems encountered.

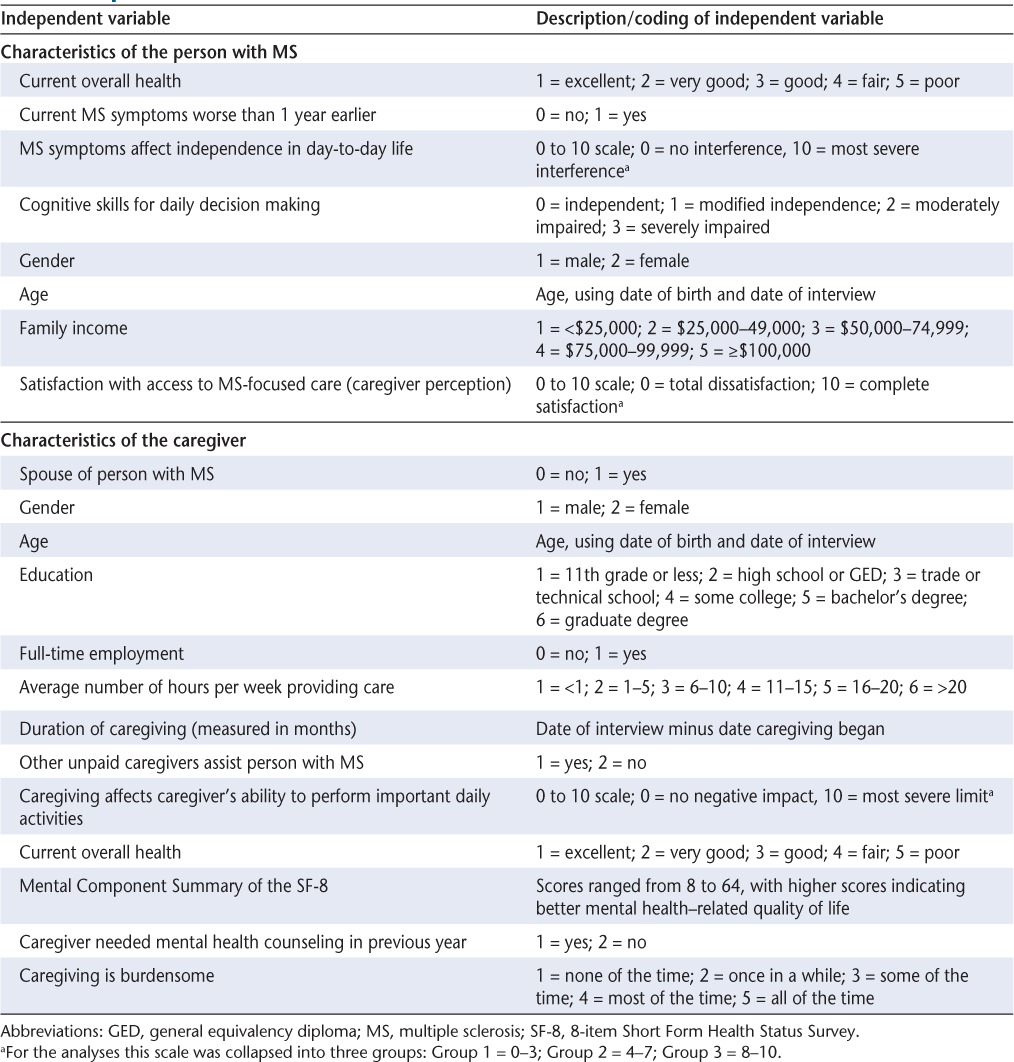

Table 1 presents the independent variables included in the study and describes how they were coded. These independent variables include MS symptoms, demographic and health assessments of the person with MS and the caregiver, time spent providing care, the impact of providing assistance on the caregiver's day-to-day life, and mental health and emotional characteristics of the caregiver. The model identified seven characteristics of caregivers, caregiving, and the person with MS that were significantly associated with the caregivers' perceptions that caregiving improved or strengthened their relationship with the person with MS, at the level of α= .05. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the independent variables associated with the person with MS, and Table 3 provides these statistics for the independent variables associated with the caregiver.

Table 1.

Independent variables used in analyses of factors associated with strengthened relationships

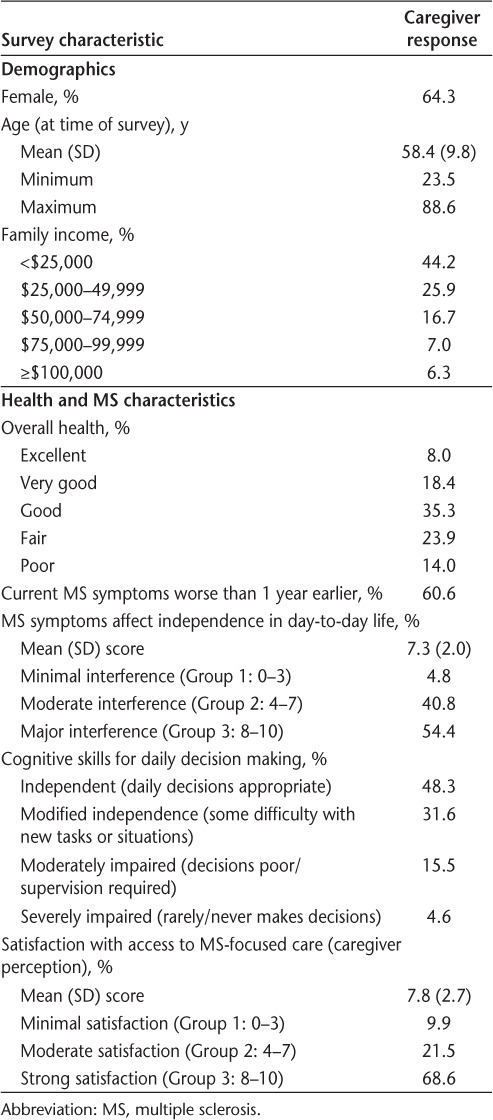

Table 2.

Characteristics of the person with MS

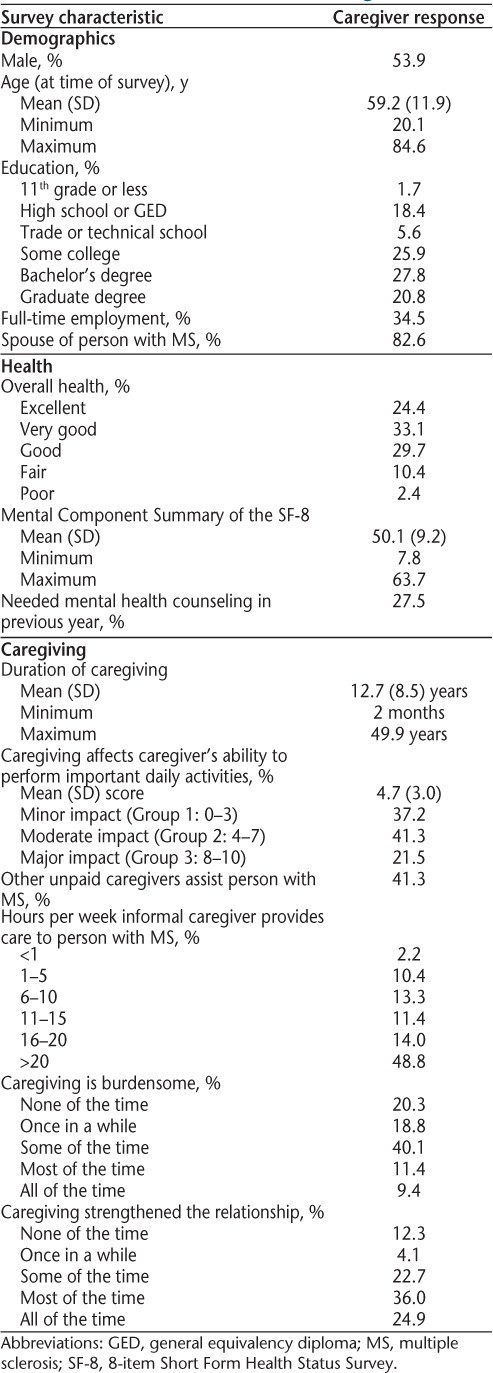

Table 3.

Characteristics of the caregiver

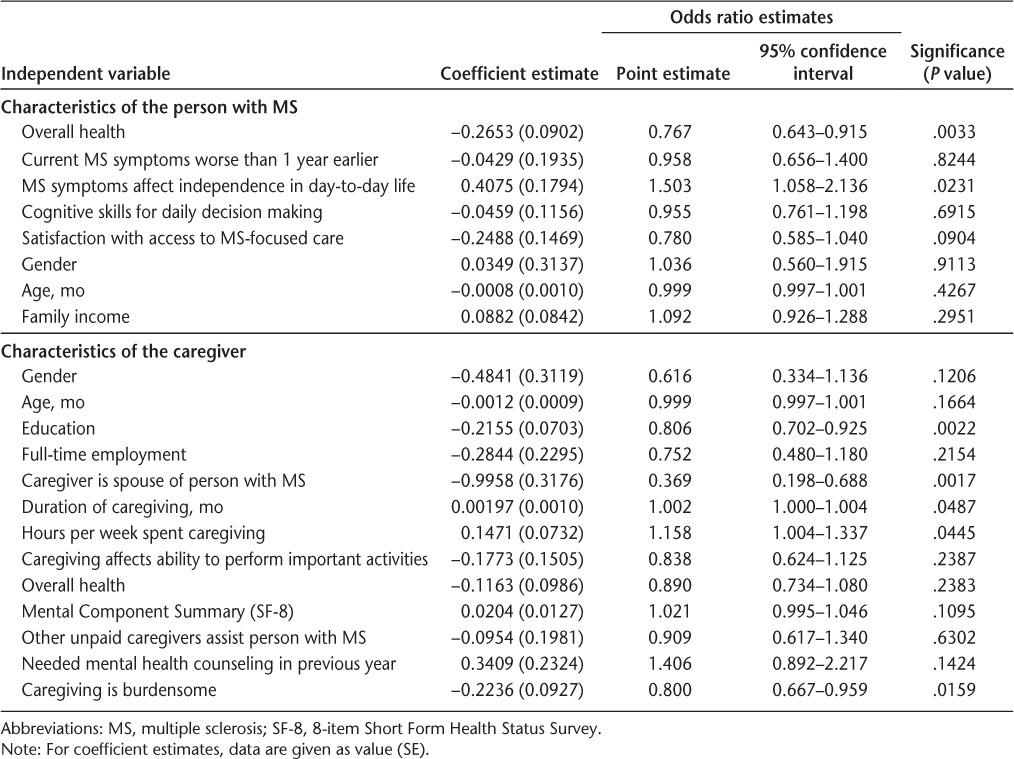

Logistic regression is utilized in the analyses of categorical dependent variables, such as these caregiver perceptions measured using this 5-point Likert item.32 Coefficient estimates and point estimates for our logistic regression model are presented in Table 4. The coefficient estimate indicates the direction of the association of each independent variable with the dependent variable (perceived strength of the caregiver/care recipient relationship). A negative coefficient estimate indicates an inverse or negative association between the independent variable and the dependent variable. The odds ratio point estimate is used to calculate the odds that the independent variable affected the dependent variable by subtracting the point estimate from 1 when the coefficient estimate is negative. For example, the point estimate for the independent variable “current overall health” of the person with MS is 0.767 (1 – 0.767 = 0.233), indicating that a one-unit decline in the overall health of the person with MS decreased the odds by 23.3% that caregiving strengthened the relationship.

Table 4.

Factors associated with caregiver perceptions of the strength of the relationship

A positive coefficient estimate indicates a direct or positive association between the independent variable and the dependent variable. Again, the odds ratio point estimate is used to calculate the odds that the independent variable affected the dependent variable. For example, the point estimate for the independent variable “MS symptoms affect independence in day-to-day life” for the person with MS is 1.503, indicating that a one-unit increase in the interference of MS symptoms with the independence of the person with MS increased the odds by 50.3% that caregiving strengthened the relationship. The statistical software SAS (SAS, Cary, NC) was used in this study.

Many characteristics from the survey, theorized to have predictive power for the caregiver/care recipient relationship based on the review of the literature, were included as independent variables in the regression analysis. For example, previous studies concluded that reduction in caregiver burden is necessary to improve health and quality of life among caregivers.12,15 We predicted that lower caregiver burden was associated with a stronger caregiver/care recipient relationship. Pakenham and Cox16 observed a negative relationship between a greater ability of the person with MS to care for themselves in the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and family relations growth and relationship opportunities. They posited that people with MS who were more independent in the performance of ADLs would require less assistance from family members, reducing the need or opportunities for family caregivers to extend relationships. Based on this previous study, we predicted that the more MS symptoms interfered with the independence of the person with MS in daily life and increased the need for informal care, the greater the opportunities for caregivers to expand, strengthen, or improve their relationship with the care recipient.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

People with MS

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for people with MS receiving care in our study, who averaged 58.4 years of age, were mostly female (64%), and generally had family incomes below $50,000 per year (70%). Almost 4 in 10 of the people with MS receiving assistance had fair (24%) or poor (14%) overall health, while about 8 in 10 either were independent (48%) or had modified independence (32%) in cognitive skills for daily decision making. The interviewer defined “modified independence” to the caregiver as the ability of the person with MS to make daily decisions that typically are appropriate and reasonable in familiar situations, while facing some difficulty with new tasks or situations. MS symptoms interfered with independence in daily life for most people with MS in our study, with about 95% experiencing at least moderate interference according to their caregivers (a response of 4 or greater on the 10-point scale used in the interview).

Caregivers

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics for the informal caregivers in our study. About 54% of the caregivers were male, and the average age was 59.2 years. Almost half of the caregivers had either a bachelor's or a graduate degree. About 83% of the caregivers were the spouse of the person with MS. Almost 90% of caregivers in our study reported that their overall health was at least good. About half of the caregivers reported that they provided more than 20 hours of assistance each week to the person with MS, while only about 13% said they provided 5 or fewer hours of informal care per week. About 63% of the caregivers replied that assisting the person with MS had at least a moderate impact on their ability to perform daily activities important to the caregiver (a response of 4 or greater on the 10-point scale provided by the interviewer). About 41% of caregivers in our study reported that other unpaid caregivers also helped the person with MS cope with the impact of their illness. About half of the informal caregivers responded that paid caregivers also helped the person with MS cope with the effects of MS on daily activities. For example, 29% of informal caregivers reported the use of paid housekeepers, and 30% reported the use of home health aides or nurses.9

Ordered Logistic Regression

As Table 4 presents, we identified a total of seven characteristics of the caregiver, caregiving, and the person with MS that were significantly associated with the caregiver's perception that providing assistance improved or strengthened their relationship with the person with MS. Worse overall health of the person with MS had a significant negative association with care-giver perceptions that providing assistance improved or strengthened the caregiver/care recipient relationship. A one-unit decline in the overall health of the person with MS (eg, from good health to fair health) decreased the odds by 23.3% that the caregiver perceived that assisting the person with MS strengthened their relationship. Conversely, we found that caregiver perceptions that MS symptoms interfered with the independence of the person with MS in daily life had a positive association with caregiver perceptions of a strengthened relationship. A one-unit increase in the interference of MS symptoms with the independence of the person with MS (eg, from minimal interference to moderate interference) increased the odds by 50.3% that caregivers perceived that assisting the person with MS strengthened their relationship. We observed that a spousal relationship between the caregiver and the person with MS had a significant negative association with perceptions of a strengthened relationship, with a spousal relationship reducing the odds that caregiving strengthened the relationship by 63.1%.

We identified four characteristics of the caregiver or the assistance provided that were significantly associated with the caregiver's perception of their relationship with the person with MS. Higher levels of caregiver education had a significant negative association with perceptions of a strengthened relationship with the person with MS. A one-unit increase in the caregiver's level of education (eg, “some college” compared with a “bachelor's degree”) decreased the odds of the caregiver reporting a strengthened relationship by 19.4%. Increased duration of caregiving and spending more hours per week assisting the person with MS had a positive impact on caregiver perceptions of the relationship. Each 1-month increase in the duration of assisting the person with MS increased the odds that the caregiver perceived a stronger relationship by 0.2%, while a 1-year increase in the duration of caregiving increased the odds of a stronger relationship by 2.4% and a 5-year increase in the duration of caregiving increased these odds by 12.5%. A one-unit increase in the number of hours per week assisting the person with MS (eg, an increase from 6–10 hours per week to 11–15 hours per week) increased the odds of the care-giver reporting a strengthened relationship by 15.8%. In contrast, we found a significant negative association between caregiver perceptions that assisting the person with MS was burdensome and the strength of the relationship with the person with MS. A one-unit increase in the perception that caregiving was burdensome (eg, an increase from “some of the time” to “most of the time”) reduced the odds of reporting a strengthened relationship by 20.0%.

Discussion

We identified a number of characteristics of the caregiver, caregiving, and the person with MS that had a significant positive association with the caregiver/care recipient relationship, as well as characteristics with a significant negative impact on this relationship. Worse overall health of the person with MS had a negative impact on the relationship. Pozzilli et al.15 found that depression in caregivers was linked to the physical, emotional, and health status of the person with MS receiving assistance. This association of health status of the person with MS with emotional distress in caregivers could affect the caregiver/care recipient relationship, supporting our finding that worse overall health in the person with MS had a negative impact on the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Economic costs of poor health can contribute to strains in the relationship between the person with MS and informal caregivers (mostly family members). For example, Iezzoni and Ngo33 reported that 21% of people with MS spent less on food and other daily necessities to pay for their health care. Worse over-all health in the person with MS would increase these financial strains, adding to pressures threatening the relationship with family caregivers.

We found a positive association between caregiver perceptions that MS symptoms interfered with the independence of the person with MS in daily life and their relationship with this care recipient, with greater interference with independence significantly increasing the odds that caregiving improved or strengthened the relationship. Pakenham and Cox16 found a negative relationship between a greater ability of the person with MS to perform ADLs independently and family relations growth and relationship opportunities. They theorized that people with MS who are more independent in the performance of ADLs would require less assistance from family members, reducing the need or opportunities for family caregivers to extend relationships. Hence, the more MS symptoms interfered with the independence of the person with MS in daily life and increased the need for informal care, the greater the opportunities for care-givers to extend relationships and strengthen or improve their relationship with the care recipient. Also, the more MS symptoms interfered with the independence of the person with MS in daily life, the greater the amount of assistance that may be required to enable the person with MS to cope with the impact of their illness. Helping the care recipient cope with the impact of MS on daily life may be rewarding to caregivers, strengthening the care-giver/care recipient relationship. Pakenham34 found that the more caregivers provided various types of assistance to the person with MS, the more likely caregivers were to find benefits in providing assistance.

We found that a spousal relationship between the caregiver and the person with MS had a significant negative impact on the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Previous studies focusing on spousal caregivers to people with MS help explain our finding. Spousal caregivers may feel that they lost their partner, companion, friend, co-parent, and lifestyle while gaining a person who needs care, with constraints and limitations imposed on the caregiver providing this assistance.10,35 In addition, a spouse assisting a person with MS may feel a loss of identity as a husband or wife while becoming a caregiver.36 Health professionals need to understand the worries and experiences of informal caregivers assisting spouses with MS so that appropriate services and support, such as respite care, can be provided.37

In our study, higher levels of caregiver education had a negative impact on caregiver perceptions that caregiving improved or strengthened the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Caregivers with more education may have broader opportunities for other rewarding activities in their lives (eg, their careers) in addition to caregiving. Time spent assisting the person with MS could reduce opportunities for more-educated caregivers to focus on these other aspects of their lives, weakening the relationship with the person with MS.

Longer duration assisting the person with MS was significantly linked to positive perceptions of the relationship. Pakenham18 found that benefit finding was linked to duration of MS caregiving, with benefit finding emerging later in the adjustment process. Similarly, we found that the number of hours per week spent assisting the person with MS was significantly related to caregiver perceptions of the relationship, with more hours providing assistance associated with an improved or strengthened relationship. A greater investment of effort in assisting the person with MS may improve the care recipient's ability to cope with the impact of MS on daily life, increasing the caregiver's feelings of benefit and thus strengthening the relationship. Our findings are consistent with a study by Pakenham34 that found that the more caregivers provided various types of assistance to the person with MS, the more likely the caregivers were to find benefits in providing assistance.

Caregiver perceptions that assisting the person with MS was burdensome had a significant negative impact on the caregiver/care recipient relationship. Providing informal assistance to a person with MS can have a negative effect on the psychological well-being of the caregiver.4,12,13,38 Strategies to reduce caregiver burden are necessary to improve the health and quality of life of caregivers and people with MS receiving their assistance.12,15 Health professionals who treat informal caregivers, as well as those treating people with MS, should be aware of the burdens and emotional strains that providing assistance places on informal caregivers. As Patti et al.39 advocate, health professionals need to be knowledgeable about educational and support programs available to caregivers assisting people with MS and refer caregivers to these programs. In addition, Pakenham18,20,22 advocates that practitioners should be sensitive to the benefit-finding themes expressed by caregivers to facilitate caregivers' efforts to identify gains in their experiences providing assistance to people with MS. Efforts to reduce caregiver burden should help strengthen the relationship between the caregiver and the care recipient.

Study Limitations

The survey sample of informal caregivers in this study was developed by contacting people with MS who participated in the NARCOMS Registry. Such participation is voluntary; thus the Registry membership is not a random sample of people with MS, resulting in possible self-selection bias. However, the Registry population is large, accounting for an estimated 10% of the MS population in the United States.25 In addition, Registry participants have age at onset of MS symptoms and demographic characteristics comparable to those of people with MS in the National Health Interview Survey and the Slifka Study (a representative national sample of people with MS).25,40,41 In addition, we surveyed caregivers who provided their perceptions of the dependency and care needs of the person with MS, as well as their perceptions of the amount of care provided. A previous study found that caregivers reported providing more frequent care and for a longer duration than people with MS reported receiving.5

Our study is a preliminary analysis of caregivers' perceptions of whether assisting the person with MS strengthened their relationship, using data collected in a large and comprehensive survey of informal caregivers.7,9 Assessing caregiver perceptions of the relationship was not the primary focus of this survey. The survey economically assessed caregiver perceptions of whether “caregiving has improved or strengthened our relationship” using a 5-point Likert item to generate preliminary data for a future comprehensive study focusing on assessments of caregiver perceptions of the relationship with the person with MS. Given the length of our care-giver questionnaire (which took about 35 minutes to complete), we did not want to add to the expense of the survey or the amount of time required to complete the interview and risk a lower completion rate by using standard instruments assessing spousal or family relationships. However, the 5-point Likert scale we developed to measure caregivers' perceptions of their relationship with the person with MS has face validity. In addition, we pretested the interview questionnaire before we began the full-scale survey.

The overall survey questionnaire was designed to learn about a range of caregiver perspectives on the caregiving process, as well as caregiver perceptions of the needs and health-related status of the person receiving this care. The survey focused on how MS and MS symptoms affected the person receiving care, the types of care provided, health insurance coverage of home-care services, and the amount of time the caregiver spent providing assistance and how providing this assistance affected the caregiver. A major objective of the overall, larger care-giver survey was to identify services and programs that could assist informal caregivers and enable people with MS to remain in the community as their disability and dependence increase. Caregiver perceptions of strengthened caregiver/care recipient relationships were only one part of this larger study.

Another possible limitation of our study is social desirability response bias and caregiver replies to our survey interview. The social desirability response bias is self-reported overestimation of culturally and socially acceptable behaviors or attitudes and underestimation of unacceptable traits.42,43 Pakenham and Cox19 found a correlation between their MS benefit-finding scale and social desirability, suggesting that there may be a social desirability response bias associated with chronic illness. In our study, informal caregivers may have believed that it was more socially or culturally acceptable to report that providing assistance to the person with MS strengthened their relationship or strengthened it to a greater degree than they really felt.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the need to reduce the burden experienced by informal caregivers assisting people with MS, given our finding that greater burden had a significant negative impact on the caregiver's relationship with the care recipient. Our analyses especially highlight the importance of addressing the needs and concerns of spousal caregivers, as a spousal relationship had a significant negative association with the strength of the caregiver/care recipient relationship. A spousal relationship reduced the odds of a strengthened relationship by 63%. Health professionals who treat informal caregivers, as well as those treating people with MS, should be sensitive to the impact caregiving has on caregivers, especially spouses providing assistance. These health practitioners need to understand the loss many spousal caregivers experience, as well as burdens, constraints, and limitations they confront when providing care. Health professionals also need to be aware of appropriate services, support, and programs that can assist informal caregivers, especially spouses. As Pakenham18,20,22 advocates, health practitioners should be sensitive to the variety of benefit-finding themes expressed by caregivers to facilitate caregivers' efforts to discover gains in their experiences providing assistance, including a strengthened or improved relationship with the person with MS.

PracticePoints.

A spousal relationship between the caregiver and the person with MS is linked to significantly lower caregiver perceptions of a strengthened relationship, highlighting the importance of addressing the needs of spousal caregivers.

Caregiver perceptions that assisting the person with MS is burdensome have a negative effect on the caregiver/care recipient relationship, demonstrating the need to reduce caregiver burden.

Health professionals treating informal caregivers, as well as those treating people with MS, should be sensitive to the impact caregiving has on care-givers, especially spouses providing assistance.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nicholas LaRocca, Associate Vice President, Health Care Delivery and Policy Research Program, and Dorothy Northrop, National Director of Clinical Programs, at the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) for their assistance with this research. The Lone Star Chapter of the NMSS recruited volunteers to pretest the caregiver survey questionnaire. The Central New England Chapter and the Ozark Branch of the Mid America Chapter of the NMSS recruited volunteers to participate in focus groups for this study. In addition, the authors are grateful to the people with MS who identified their caregivers and the caregivers who participated in the focus groups, the pretest of the survey questionnaire, and the telephone interviews. Without their cooperation and input, this study could not have been completed.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by a contract (HC 0043) from the Health Care Delivery and Policy Research Program of the NMSS.

References

- 1.Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L, Srinath KP, Perloff JN. Disability in elderly people with multiple sclerosis: an analysis of baseline data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:55–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Study renewed. NMSS Research Highlights, Winter/Spring 2007. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/download.aspx?id=77. Accessed March 10, 2011.

- 3.McKeown LP, Porter-Armstrong AP, Baxter GD. Caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis: experiences of support. Mult Scler. 2004;10:219–230. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1008oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKeown LP, Porter-Armstrong AP, Baxter GD. The needs and experiences of caregivers of individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:234–248. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr618oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson KJ, Cleghorn G, Goldenberg E. Assistance arrangements and use of services among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Disabil Rehabil. 1996;18:354–361. doi: 10.3109/09638289609165894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carton H, Loos R, Pacolet J, Versieck K, Vlietinck R. A quantitative study of unpaid caregiving in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2000;6:274–279. doi: 10.1177/135245850000600409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Chakravort B, Tyry T. Perceptions of informal care givers: health and support services provided to people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:500–510. doi: 10.3109/09638280903171485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Hara L, DeSouza L, Ide L. The nature of care giving in a community sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1401–1410. doi: 10.1080/09638280400007802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan RJ, Radin D, Chakravort B, Tyry T. Informal care giving to more disabled people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1244–1256. doi: 10.1080/09638280802532779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buhse M. Assessment of caregiver burden in families of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;40:25–31. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200802000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera-Navarro J, Benito-Leon J, Oreja-Guevara C. Burden and health-related quality of life of Spanish caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2009;15:1347–1355. doi: 10.1177/1352458509345917. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan F, Pallant J, Brand C. Caregiver strain and factors associated with caregiver self-efficacy and quality of life in a community cohort with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1241–1250. doi: 10.1080/01443610600964141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Figved N, Myhr KM, Larsen JP, Aarsland D. Caregiver burden in multiple sclerosis: the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1097–1102. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbes A, While A, Mathes L. Informal carer activities, carer burden and health status in multiple sclerosis. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:563–575. doi: 10.1177/0269215507075035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pozzilli C, Palmisano L, Mainero C. Relationship between emotional distress in caregivers and health status in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:442–446. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1046oa. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pakenham KI, Cox S. Development of the benefit finding in multiple sclerosis (MS) caregiving scale: a longitudinal study of relationships between benefit finding and adjustment. Br J Health Psychol. 2008;13:583–602. doi: 10.1348/135910707X250848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pakenham KI. The nature of benefit finding in multiple sclerosis. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:190–196. doi: 10.1080/13548500500465878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pakenham KI. The positive impact of multiple sclerosis (MS) on carers: associations between carer benefit finding and positive and negative adjustment domains. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:985–997. doi: 10.1080/09638280500052583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pakenham KI, Cox S. The dimensional structure of benefit finding in multiple sclerosis and relations with positive and negative adjustment: a longitudinal study. Psychol Health. 2009;24:373–393. doi: 10.1080/08870440701832592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pakenham KI. The nature of sense making in caregiving for persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1263–1273. doi: 10.1080/09638280701610320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pakenham KI. Making sense of illness or disability: the nature of sense making in multiple sclerosis (MS) J Health Psychol. 2008;13:93–105. doi: 10.1177/1359105307084315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pakenham KI. Making sense of caregiving for persons with multiple sclerosis (MS): the dimensional structure of sense making and relations with positive and negative adjustment. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15:241–252. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Volmer T. Comorbidity delays diagnosis and increases disability at diagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2009;72:117–124. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000333252.78173.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Project. Welcome to the NARCOMS Registry. 2011. http://narcoms.org/. Accessed March 10, 2011.

- 25.Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Volmer T. Comorbidity, socioeconomic status and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14:1091–1098. doi: 10.1177/1352458508092263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Project. Become a participant. 2011. http://narcoms.org/becomingaparticipant. Accessed March 10, 2011.

- 27.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Minimum Data Set (MDS)–Version 2.0–for Nursing Home Resident Assessment and Care Screening. Basic Assessment Tracking Form. 2000. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS20MDSAllForms.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2011.

- 28.Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003–1012. doi: 10.1023/a:1026179517081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to Score and Interpret Single-Item Health Status Measures: A Manual for Users of the SF-8TM Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchanan RJ, Huang C, Kaufman M. Health-related quality of life among young adults with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2010;12:190–199. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPSR Health Plan Survey 3.0 Adult Commercial Questionnaire. 2006. https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/CAHPSkit/files/ce151ad_engadultcom_3.0.doc. Accessed March 10, 2011.

- 32.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iezzoni LI, Ngo L. Health, disability, and life insurance experiences of working-age persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2007;13:534–546. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pakenham KI. The nature of caregiving in multiple sclerosis: development of the caregiving tasks in multiple sclerosis scale. Mult Scler. 2007;13:929–938. doi: 10.1177/1352458507076973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheung J, Hocking P. The experiences of spousal caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis. Qualitat Health Res. 2004;14:153–166. doi: 10.1177/1049732303258382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mutch K. In sickness and in health: experience of caring for a spouse with MS. Br J Nurs. 2010;19:214–219. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2010.19.4.46782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung J, Hocking P. Caring as worrying: the experience of spousal carers. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:475–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knight RG, Devereux RC, Godfrey HP. Psychosocial consequences of caring for a spouse with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1997;19:7–19. doi: 10.1080/01688639708403832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patti F, Amato MP, Battaglia MA. Caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a multicentre Italian study. Mult Scler. 2007;13:412–419. doi: 10.1177/1352458506070707. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marrie RA, Hadjimichael O, Vollmer T. Predictors of alternative medicine use by multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2003;9:461–466. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms953oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden L. The Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study: methods and sample characteristics. Mult Scler. 2006;12:24–38. doi: 10.1191/135248506ms1262oa. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Logan DE, Claar RL, Scharff L. Social desirability response bias and self-report of psychological distress in pediatric chronic pain patients. Pain. 2008;136:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson K, Baranowski T, Thompson D. Innovative application of a multidimensional item response model in assessing the influence of social desirability on the pseudo-relationship between self-efficacy and behavior. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(suppl 1):i85–i97. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl137. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]