Abstract

The aim of this study was to elucidate the experience of self-management among people with multiple sclerosis (MS) and gather their input to inform a self-management intervention. Twelve people with MS participated in focus groups in which they were asked open-ended questions about MS symptoms, challenges, overcoming challenges, symptom management, and treatment preferences. The results suggest four major themes: 1) “The Everyday Experience of MS,” including comments about symptoms and their impact on functioning; 2) “Motivation for Self-Management,” including descriptions of motivation originating from physical necessity, success with other management techniques, and external sources; 3) “Coping Strategies and Skills,” including descriptions of changing behaviors, expanding social support networks, finding resources, utilizing medical treatment, and monitoring symptoms; and 4) “Vision for a Self-Management Intervention,” including suggestions that an intervention be individualized, be motivating, and provide resources. The results of this study can inform the design and implementation of self-management interventions. Experiences described by participants are consistent with other qualitative reports suggesting the active role people with MS play in managing their condition. Intervention approaches must consider the complex constellation of symptoms associated with MS and provide individualized treatments that enhance the person's ability to manage their symptoms, barriers presented by such symptoms, and their health care.

People living with chronic diseases self-manage their conditions.1 They decide whether or not to adhere to medical routines, to exercise, to participate in social activities and roles, and to use the health-care resources available to them. Self-management is based on the idea that those with a chronic condition should take an active, central role in managing their disease, secondary conditions, and health care. It is rooted in cognitive-behavioral theory and is thought to enhance outcomes by improving self-efficacy for managing the chronic health condition, skill-building (including problem-solving skills), and obtaining support to change. Evidence to support the effectiveness of self-management interventions has been reported for many chronic conditions, including arthritis, asthma, HIV/AIDS, limb loss,2 and back pain.3 Self-management techniques have been applied to people with multiple sclerosis (MS) to manage their fatigue.4,5

Self-management interventions seem especially appropriate for people living with MS because they face a constellation of symptoms that vary from day to day and over the course of years. Pain, fatigue, depression, and cognitive impairment often co-occur, and the effect of all may be greater than the sum of each individually (eg, depression can worsen fatigue and cognitive impairment can worsen depression).6–8 Consideration of the co-occurrence of secondary conditions in the context of overall disease symptoms and burden is thought to be critical for successful assessment and clinical intervention in MS.9

Although rehabilitation and psychological treatments exist for individually addressing many of the specific conditions associated with MS, interventions typically do not focus on how to manage the constellation of symptoms. While it is known that people with MS and other chronic conditions develop coping techniques to self-manage their disease, little is understood about the complex experience of self-management in MS. Qualitative data collection, including focus groups, is an ideal way to learn how people with MS cope with their symptoms and can inform efforts to provide treatment to enhance these skills.10,11 The objectives of this study were to 1) elucidate the experience of self-management among people with MS, and 2) gather their input to inform a self-management intervention intended to increase self-efficacy and to provide a practical skill set for coping with the constellation of secondary conditions associated with MS.

Methods

Participants

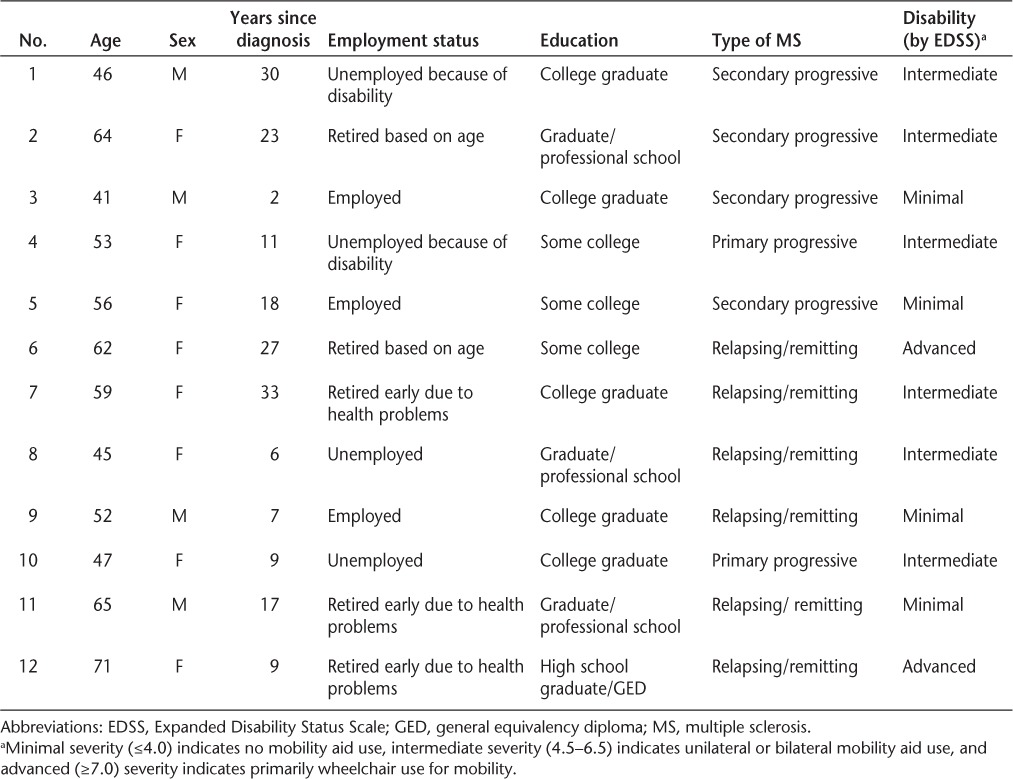

Potential participants were identified through involvement in previous research studies and through the Greater Washington chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), which serves 23 counties in Washington. Recruitment was done through invitation letters, advertisements in the organization's newsletter, self-help groups, and the NMSS website. We used special case purposive sampling,12 in which we intentionally oversampled people with moderate disability (no less than 2 years since diagnosis and minimal or intermediate disability on the Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]) who potentially could be users of or benefit from self-management. Eligible participants were aged 18 years or older, with physician-diagnosed MS and the ability to travel to the University of Washington without financial or logistical support. Individuals received payment of $25 for their participation. We recruited consecutive responders. Twenty people were scheduled for two focus groups, and 12 people participated: 5 in the first group and 7 in the second. (Travel difficulty or illness prevented attendance for some people originally scheduled to participate.) Demographic information about participants is shown in Table 1. The group composition is typical of the larger MS population: mostly women (67%), aged from 41 to 71 years, most with at least a college education (67%). All recruiting and focus group methods were approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Committee.

Table 1.

Characteristics of focus group participants

Focus Groups

This study used focus group methods to examine the experience of self-management among people with MS. Focus groups were selected for the study because conversation in the group may trigger recall of experiences by those with memory or attention difficulty, and because discussion can help to identify areas of agreement and disagreement.13 Participants first completed a brief demographic questionnaire and then took part in focus group discussion. Focus groups lasted approximately 2 hours and were held at the University of Washington in Seattle, a facility that is both centrally located and accessible to people with disabilities. Discussion was moderated by a team of two University of Washington Department of Rehabilitation Medicine faculty members who were trained, experienced facilitators. One researcher was the primary facilitator; the other contributed when appropriate. Three additional staff members served as note takers. A discussion guide was developed that included questions such as, “What have you learned about managing your MS that you think will be helpful to others?” Questions set the agenda but did not confine the discussion—direction of the conversation was driven by the flow of the discussion, with the guide serving as a reminder of key questions and points to ask. To explore participants' self-management techniques, a series of open-ended questions were asked regarding symptoms, challenges, overcoming challenges, and how people managed their symptoms. Additional questions asked about treatment preferences relating to intervention format, delivery, and content.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were recorded using real-time transcription by a court reporter and digital audio recording. Transcripts and field notes were read several times in order to identify the main issues expressed. Next, a short list of codes were formed that indicated important concepts from the focus group data and from self-management literature used to develop the study design. These initial codes were then expanded into a codebook using open coding of transcript quotes that explored additional, deeper themes. The themes were reviewed and discussed by the entire research group. This process continued until all authors agreed that the themes accurately reflected the information provided in the focus groups and that the second focus group added no new themes beyond those identified in the first group. ATLAS.ti Version 5.0 (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) was used to organize and code the data.

Results

Our findings revealed the complex experience of self-management for people with MS and identified key areas that an intervention should address. Four major themes and 13 subthemes emerged from the analysis of focus group discussions. These themes are described below.

The Everyday Experience of MS

Focus group discussion painted a vivid picture of the everyday experience of people living with MS. As expected, participants listed numerous symptoms they managed as a result of having MS, including fatigue, pain, cognitive disability, mobility issues, and vision problems. In addition to the secondary symptoms of MS itself, several people described the association between MS and other diseases, such as arthritis and depression, while others recognized that they were vulnerable to unrelated health issues, such as breast cancer. Several key themes emerged that characterized their MS experience.

Shaping the Way We Live

Participants shared with the group descriptions of their disability and how it affected their quality of life. Many depicted an ongoing, daily struggle to manage their current symptoms and prepare for an unpredictable future. One 52-year-old male participant said that his symptoms “shaped the way I live and look at everything.” Some described a constant flux of improvements and setbacks. One 45-year-old female participant summed up this experience: “But as I've adjusted to it, my cognitive skills have gotten so much worse that it's like a tap dance. It's two steps forward, three steps back. Two steps forward, one step back.” While most participants acknowledged the challenges of the disease, some also felt that MS had transformed their lives for the better. In particular, many said that having to reduce their work hours or quit working altogether as a result of their MS gave them a life balance they did not have before.

Acceptance and Adjustment

Even in the face of severe disability, many participants described their experience of accepting MS and adjusting to the changes it brought to their lives. One 45-year-old female participant said about this process, “You have to accept it on some level. Or, again, you go through the crazies. If you don't accept it, what are you going to do with it? If you deny it, that's certainly not helpful for your health.” Another participant, a 52-year-old man, said that over time he had redefined what was normal for him: “Normal isn't the way I used to live. My normal is disabled. But I'm able to adapt to that.”

Motivation for Self-Management

Study participants also shared several specific triggers that led them to self-manage their condition.

Out of Necessity

Participants described being moved to self-manage as a result of physical necessity, when they realized that making changes was essential to functioning. One 52-year-old male participant described using pacing techniques only because his MS prevented him from keeping up his normal activity level: “I started doing it because I had to. I mean I was so opposed to pacing. I was full speed ahead, you know, run through the wall. Win one for the Gipper and it was very, very hard for me. I only started pacing because I had to.” Several participants described having this insight at work. One 45-year-old woman experienced great physical strain before realizing she had to quit her job: “But at the end of the hours and just the physical walking and the energy that it took, I would literally crawl to my car. And after doing that for so many months and having the numbness and one time I sat down with my family I couldn't use my right hand to eat dinner. I said I'm just not hungry. My husband knew. He said it just isn't worth it. You just need to step down.”

Seeing Success

Many participants found that they increased their use of self-management strategies after having success with other coping strategies they had used in the past or were currently using. Once they realized the effectiveness of specific strategies, they continued their use and attempted others. One 65-year-old male participant found that taking naps allowed him to increase his functioning, and this encouraged him to continue to employ that strategy: “You had to walk away and then maybe come back to the problem at a different time. Then when it's time to lie down and rest, it's better. I'll get more accomplished if I take a rest than if I fight it.”

External Motivation

Finally, a few participants identified sources of external motivation to employ self-management strategies. Participants described the positive impact of specific advice or encouragement from health-care providers, friends, family, and others in their lives. One 56-year-old female participant summed up this source of motivation when she described what she needed from health-care providers and others in her life: “I was just overwhelmed with the idea that my body was eating itself . . . And I didn't need somebody feeling sorry for me. I needed somebody saying, okay, you're a grown-up, what are you doing?”

While many participants identified external sources of positive motivation, others described instances where people in their lives had a negative impact on them. Several shared the common experience of having their symptoms, particularly fatigue, misunderstood and dismissed. One 41-year-old male participant described a common scenario at his workplace: “I did a lot on Sunday and that's why I missed work on Tuesday, and I was so tired. To people it seems, gee, sometimes he sleeps all day.”

Coping Strategies and Skills

The final piece of the self-management experience that came out of the focus group discussion was the use and development of management strategies. Participants revealed a range of diverse coping techniques to manage their MS symptoms, improve their function, and enhance their quality of life.

Changing Behaviors

The most common coping strategy was to change behaviors. Often, multiple co-occurring changes improved functioning at work and at home, and allowed participants to function despite considerable disability. Many participants described regularly exercising to help them perform activities, including walking, yoga, swimming, and lifting weights. One 52-year-old male participant prioritized “time for long walks . . . no matter what time of the day.” One 56-year-old female participant found that exercise ameliorated her depression: “I learned this a long time ago. I started exercising because I was too blue. And it really helped.” In addition, several participants applied changing behaviors in the workplace, such as altering their work schedule. Others recognized that work of any kind was no longer possible. One 65-year-old male participant related, “I was a schoolteacher. I didn't know why I was getting so tired all the time. Then when I found out why, I quit.”

Increasing Social Support

Creating and enhancing social support networks was another way participants managed the impact of their MS. Many participants described peer support systems, such as MS support groups and exercise classes for people with MS. Participants also described the camaraderie and motivation they felt when talking with others who have MS. One 71-year-old woman said about an educational class for people with MS, “It's great to be among people with MS. I go to a support group meeting once a month, too. But it's just nice, it's just nice to talk . . . it validates who we are, you know.”

Many also felt that these peer networks increased their understanding of MS. Several participants found that their knowledge of their disease deepened as a result of hearing others' experiences. One 45-year-old female participant summed up this idea as follows: “It's educational. I remember going to one of these follow-up meetings and a woman said, ‘Oh, I've lost my sense of taste.' And that's attributed to MS and that was good to know. So you don't feel like you're going crazy that it happens to you.”

It also became apparent that these types of activities were not for everyone. Some participants stated that it was difficult to spend time with other people experiencing progressing disability. One 46-year-old male participant said, “I belong to a support group that I only go to about once or twice a year. I get sick of sitting around the table and listening to everybody.”

Information Is Critical

Accessing information about MS and strategies to improve functionality was another component of participants' self-management toolkits. Many sought out information from community resources, such as the NMSS, to learn more about their disease. Others described gathering information from health-care providers, including physicians, occupational therapists, and others. Providers were identified as a critical source of information and clarification about symptoms, triggers, diagnosis, and other information. According to one 62-year-old woman, “I get information from other people. I talk to some experts. I've had an occupational therapist come into my house and tell me what I need to do to make it easier for me to live. I get on the Web site—yeah. I have good doctors that tell me things.”

Utilizing Medical Treatment

To complement other management strategies, many participants took medication and received medical treatment to mitigate symptoms. Overall, participants felt that medical treatment was critical to their functioning. In the case of one 56-year-old woman, medication—in conjunction with other behavioral changes—allowed her to continue her exercise regimen: “The medication really works well in helping me out. Usually, I've developed this routine where I get to take a nap before I go the gym. I'll go to work and take a nap, and I'll get—by the time I get to the gym, the medication has kicked in and I'm refreshed from this nap. And that really seems to help. I don't think I could do exercise without it.”

Monitoring and Prevention

In conjunction with specific coping techniques, most participants described a constant vigilance and heightened awareness of the effects of MS. One 52-year-old male participant shared his experience of increased vigilance at his workplace: “I started to make goofs and I was always very accurate . . . But it just came down to where I double check now I triple check. I don't know if I can blame that on MS or what. I think it helps me just being conscious that I'm more prone to error than normal. So I take the extra time to double check things, triple check things, then go on my way.” Others described prioritizing activities and pacing themselves in order to conserve energy. Participants learned to plan around MS symptoms and made adjustments to both prevent symptoms and mitigate their impact. One 47-year-old female participant shared how this prevention strategy played out on a given day: “The pacing is important because, for example, Wednesdays go to physical therapy, come home, take a nap for a couple hours, go to yoga, come home, rest again. I have to really monitor the difference between getting tired to being able to stop that and have a chance to recover.” Several described learning to be more aware of and avoid key triggers of symptoms, such as heat, stress, and overexertion.

Vision for a Self-Management Intervention

Participants' experience of MS and self-management provided insights into the challenges, motivations, and strategies of managing this disease. After a discussion of this experience, focus group participants were asked to provide feedback on an intervention that could enhance coping skills for themselves and others with MS.

Addressing the Unique MS Experience

First, participants felt that the intervention should be flexible enough to address not only the complexity but also the diversity of the disease. Every aspect of the intervention—from goals set, to content used, to format and medium—should be individualized. Specifically, participants said that it was important that the content core of the intervention change based on the stage of the disease and the range of physical and cognitive needs.

Others described the importance of having a format and medium that took into account both individuals' disability and their comfort with technology. Some participants, such as one 53-year-old woman, suggested having materials to follow along with so that they “don't have to depend entirely on listening skills.” Despite personal preferences, overall they endorsed the idea of having multiple media and delivery methods to meet individual needs. One 45-year-old female participant summed up this idea: “You don't know what the comfort level is with the person. Some people are comfortable on the computer, other people would rather work off paper.”

Enhancing Motivation

Participants felt it was critical that an intervention motivate people to use self-management strategies. Specifically, focus group participants suggested that the intervention help people set finite, personalized, and achievable goals, and offer support to reach those goals. Several participants felt that this would provide a sense of progress. One 45-year-old female participant said, “I would think you'd want to have some sort of benchmarks or milestones built into the program. So that someone feels they're kind of making some sort of accomplishment.” A 56-year-old female participant said that offering this kind of direction was critical, without which managing MS “seemed like an endless road to nowhere.”

A few participants felt that the intervention should be grounded in a strong connection between the inter-ventionist and the patient. This would help the patient be more invested in the work being done and motivated to accomplish more. One 52-year-old male participant said, “I think that would be helpful for an interviewer or counselor was able to kind of push, you know, nudge.”

Information Sharing and Self-Management

Finally, participants wanted an intervention that enhanced existing self-management skills while developing new ones, specifically the ability to access and use information. Several participants suggested that the intervention should directly provide resources and information about MS. One 62-year-old female participant said that having a source of information in addition to her health-care provider would be important to her during a health crisis: “I would have liked to know that there was somebody I could call, other than my own, I mean, I talked to my doctor.”

A few participants, such as one 47-year-old woman, also suggested that these resources could be some of the “takeaways” of the intervention, “so that when you're progressing through the 8- to 10-week program you have something to refer to. Then when it's done it's not over. You have some resources.” Many participants felt that providing information alone was not sufficient; they also wanted to increase their problem-solving skills. Despite the overall endorsement of information sharing and problem solving, a few participants indicated that they had had the disease so long that they knew all there was to know. One 62-year-old female participant said, “I feel like it would be something that would be very good for somebody who is newly diagnosed or recently diagnosed. For me, who has had it for 25 years, there's not much new out there.”

Discussion

Experiences described by the participants in this study are consistent with other qualitative reports that suggest the active role of people with MS in managing their condition. For example, participants in a focus group study suggested that coping with MS involved maintaining active control over one's life.10 Participants said that picking and choosing activities allowed them to alter their lifestyles while maintaining control. In a series of semi-structured interviews with people with MS about work activities both inside and outside the home, participants explained how they changed the way they did things in order to perform valued activities.14 The strategies they used did not focus on a single problem, such as memory or fatigue, but rather concentrated on a more general set of skills, including the identification of precipitating factors, development of self-monitoring skills and vigilance, and construction and later evaluation of a set of strategies. This skills set could be applied to a variety of activities in many different settings.

Based on this and other studies, it can be argued that well-designed self-management programs have an important place in MS care. Such programs typically provide not only education but also a set of skills that can be used to manage a variety of challenges faced by people with MS. Key skills include 1) knowledge acquisition, 2) self-monitoring, 3) problem solving and goal setting, 4) skill acquisition (eg, cognitive coping skills, relaxation skills, activation, and mindfulness), 5) identifying and building upon existing strengths, and 6) rehearsal of coping and self-management skills.15,16 Intervention approaches are needed that take into account the complex constellation of symptoms associated with MS and provide individualized treatments that enhance the person's ability to manage their symptoms, barriers presented by such symptoms, and their health care in the context of their preferences. Such intervention approaches would rely on the contributions of many health-care providers and consumer organizations.

The current study has several limitations that point to future research directions. In addition to the relatively small sample size, people in the moderate range of severity were selected for participation because we believed that since they were likely to experience multiple symptoms, they would be good informants with respect to skills and strategies for coping with these symptoms. The self-management needs of people who are newly diagnosed or in the advanced stages of MS may be different. The experiences of people in these groups need to be explored. Our focus group included only those who had been diagnosed with MS. Clearly, caregivers or partners of people living with MS have an important role in self-management.17 The perspectives of how couples with MS manage the condition would also be an important area for future investigation.

Conclusion

Participants in this study provided useful insights into the experience of living with MS, which can inform the design and implementation of self-management intervention programs. Participants reported how MS shaped the way they live and how they used coping strategies and skills that allowed them to continue to participate in valued activities and roles. Among the strategies described were changes in behavior, increasing use of social support, acquiring pertinent information, using medical treatment, and being vigilant in order to recognize warning signs of future problems. They indicated that their use of the strategies arose out of necessity and was triggered by the presence of symptoms coupled with the desire to maintain function. They were motivated by the success they had with current strategies to continue their use or develop new ones. While they found that advice and feedback from others was helpful at times, at other times it was not. Participants clearly described the help they needed. Every aspect of the program should be individualized, including goals, content, format, length, and follow-up. They felt that support materials were essential but wanted that material presented as a menu of options, including written material and web-based resources. Setting specific, achievable goals was felt to be a way of enhancing motivation for continued strategy use.

Practice Points.

Because people living with MS experience multiple symptoms that interfere with participation in valued activities and roles, they use a number of strategies to manage their condition.

Use of these strategies is triggered by symptoms coupled with the desire to maintain function, and continued use is motivated by the success of the strategy.

Programs to assist people in the self-management of MS should be individualized in terms of content, goals, format, and length. Setting specific, achievable goals is an excellent way to promote continued strategy use.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: The contents of this article were developed under a grant from the US Department of Education, National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) grant number H133B080025. However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and endorsement by the federal government should not be assumed.

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumback K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;2888:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wegener ST, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim P, Ehde D, Williams A. Self-management improves outcomes in persons with limb loss. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.08.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlayson M, Holberg C. Evaluation of a teleconference-delivered energy conservation education program for people with multiple sclerosis. Can J Occup Ther. 2007;74:337–347. doi: 10.2182/cjot.06.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matuska K, Mathiowetz V, Finlayson M. Use and perceived effectiveness of energy conservation strategies for managing multiple sclerosis fatigue. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:62–69. doi: 10.5014/ajot.61.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarci O, Wingerchuk D. Epidemiology and natural history of multiple sclerosis: new insights. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:248–254. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000227033.47458.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chwastiak LA, Gibbons LE, Ehde DM. Fatigue and psychiatric illness in a large community sample of persons with multiple sclerosis. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.001. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehde DM, Osborne TL, Hanley MA, Jensen MP, Kraft GH. The scope and nature of pain in persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2006;12:629–638. doi: 10.1177/1352458506071346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraft GH, Johnson KL, Yorkston K. Setting the agenda for multiple sclerosis rehabilitation research. Mult Scler. 2008;14:1292–1297. doi: 10.1177/1352458508093891. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Courts NF, Buchanan EM, Werstlein PO. Focus groups: the lived experience of participants with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA. Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S12–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yorkston KM, Johnson K, Klasner ER, Amtmann D, Kuehn CM, Dudgeon BJ. Getting the work done: a qualitative study of experiences of individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25:369–379. doi: 10.1080/0963828031000090506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effect Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH. Self-management education programs in chronic disease: a systematic review and methodological critique of the literature. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1641–1649. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.15.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starks H, Morris M, Yorkston K, Gray R, Johnson K. Being in- or out-ofsync: a qualitative study of couples' adaptation to change in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32:196–206. doi: 10.3109/09638280903071826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]