Abstract

Although injection-site reactions (ISRs) occur with US Food and Drug Administration–approved injectable disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis, there are currently few reports of real-world data on ISR management strategies or possible correlations between ISRs and patient demographics, disease characteristics, and missed injections. Patient-reported data on the use of DMTs, patient demographic and disease characteristics, missed injections, and ISR reduction strategies were collected via e-mail, a patient registry (www.ms-cam.org), and a Web-based survey. Of the 1380 respondents, 1201 (87%) indicated that they had used injectable DMTs, of whom 377 (31%) had used intramuscular (IM) interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a), 172 (14%) had used subcutaneous (SC) IFNβ-1a, 183 (15%) had used SC IFNβ-1b, and 469 (39%) had used glatiramer acetate (GA). The majority of respondents were older (73% were ≥40 years), female (79%), married or living with a partner (72%), white (94%), and nonsmoking (82%). Injection-site reaction incidence, grouped according to severity, varied among DMTs, with IM IFNβ-1a causing significantly (P < .001) fewer mild, moderate, or severe ISRs than the other therapies. Female sex and younger age were significantly (P < .05) associated with more moderate ISRs among users of IM IFNβ-1a, SC IFNβ-1b, and GA. Nonwhites reported severe ISRs more often than whites. For all DMTs injection-site massage and avoidance of sensitive sites were the most frequently used strategies to minimize ISRs. These data may help identify patients with characteristics associated with a higher risk for ISRs, allowing health-care professionals to provide anticipatory guidance to patients at risk for decreased adherence or discontinuation.

Between 1993 and 2002, four injectable disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in multiple sclerosis (MS) therapy: subcutaneous interferon beta-1b (SC IFNβ-1b; Betaseron, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ), intramuscular (IM) IFNβ-1a (Avonex, Biogen Idec, Inc, Cambridge, MA), SC IFNβ-1a (Rebif, Serono, Inc, Rockland, MA), and SC glatiramer acetate (GA; Copax-one, Teva Neuroscience, Inc, Kansas City, MO).1–4 A fifth injectable DMT (SC IFNβ-1b; Extavia, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp, East Hanover, NJ) received FDA approval in 2009, after this study was completed.5 Multiple clinical trials have shown that treatment with these injectable DMTs reduces the frequency of relapses and slows disease progression.6–9 Although the MS treatment armamentarium is changing with the addition of infused and oral therapies that have recently become available or will be available soon, injectable DMTs remain critical in the treatment of this disease.

One limitation of injectable DMT use for MS is the relatively high rate of treatment discontinuation, estimated to range from 24% to 40% over periods of 2 to 5 years.10–13 Among the patient-provided reasons for discontinuing therapy are the side effects of DMTs, specifically injection-site reactions (ISRs). In one report, the primary reasons for discontinuation among the 14% of patients who discontinued IFNβ therapy after experiencing associated side effects were ISRs (16%), flu-like symptoms (23%), depression (21%), and fatigue (21%).11 Another study found that among patients taking GA, ISRs were the most important side effect leading to discontinuation.14 Skin reactions influence not only discontinuation rates, but also adherence rates. Indeed, approximately 12% of missed injections may be related to pain at the injection site or other skin reactions.14 Not surprisingly, skin reactions are less common and appear to be less likely to cause discontinuation in users of the IM injectable therapy.1–5,14,15

Injection-site reactions as a side effect of injectable DMTs have important implications for both discontinuation and adherence. However, few large patient surveys have reported effective strategies for managing ISRs. Moreover, little is known about the relationships between ISRs and patient demographic variables, disease characteristics, and the frequency of missed injections.

Methods

Study Design

Self-reported patient data on ISR occurrence and use of injectable DMTs were collected using e-mail, a patient registry (www.ms-cam.org), and a Web-based survey instrument. The observational online survey collected descriptive information regarding the use of injectable DMTs, ISRs, disease characteristics, and how respondents with MS addressed the challenges presented by DMT-associated ISRs. For the purposes of this study, the population of interest was patients with MS who were using injectable DMTs. However, given that the respondents were from a self-selected registry that may not be completely representative of this population of interest, any generalizations based on the results should take account of this limitation.

Data Collection

Data were collected from a registry of patients with MS that has been maintained by the Rocky Mountain MS Center since June 2000. At the time of the reported survey, there were approximately 18,000 individuals with self-reported MS in the registry. This registry contains e-mail addresses and related unique, anonymous identifiers in a privately held, protected file. Individual patient participants also are given the opportunity to create passwords so that they can log into the server. These methods of data collection ensure both patient anonymity and secure information transfer and have previously been described in detail.16

MS registry participants were recruited through a variety of sources, including the Rocky Mountain MS Center (www.mscenter.org) and National Multiple Sclerosis Society (www.nationalmssociety.org) websites. To a lesser extent, patients also learned about this registry through in-office clinic visits or by attending programs presented by clinicians affiliated with the Rocky Mountain MS Center. Typically, registrants were referred to www.ms-cam.org for MS-specific information pertaining to an evidence-based approach to integrative medicine. Thus, it is likely that users registered at www. ms-cam.org to gain access to such information and to participate in survey research. Because the results of Rocky Mountain MS Center surveys are made available to MS registry participants, the opportunity to learn about the experiences of others with MS is an incentive for patients to register. All data collected using patient self-reports and responses from individual registrants remain anonymous.

This Multiple Sclerosis–Injection Site Reaction (MS-ISR) survey was initiated through e-mails sent to the subset of registered patients who had expressed interest in participating in surveys and also demonstrated an ability to complete administered surveys. The methodology and specific content of the MS-ISR survey were approved by a local institutional review board. A subset of these data was previously presented in a preliminary format.17 The MS-ISR survey instrument was designed by the authors and carefully reviewed by clinicians subspecializing in MS, although it did not undergo preliminary patient testing and evaluation prior to its administration. Patients who received regular medical care and who self-identified as having used injectable DMTs were asked about a number of other factors that might contribute to their ISRs, such as injectable medication used and time on current medication. Respondents were also asked to indicate whether they had tried any of ten possible strategies, compiled from multiple sources as well as the authors' own clinical experience, to prevent or relieve their ISRs. In addition, respondents were asked about their use of autoinjectors. For the purpose of this survey, no attempt was made to validate the effectiveness of any of these strategies. Disability data were also collected using the Patient-Determined Disease Steps model.18,19

Although ISRs are universally recognized to be an issue with the use of injectable DMTs for MS, the term currently has no standard definition, nor is there any widely accepted method for grading the severity of ISRs. In the present survey, respondents were asked to rate both the frequency with which they experienced ISRs (rarely, sometimes, or often) and the seriousness of these ISRs according to three categories: 1) “mild”—usually transient and involving heat, redness, swelling, and/or bruising; 2) “moderate”—possibly not transient, involving discomfort, and involving itching, pain, lumps, dimpling, and/or skin sores; and 3) “severe”—including scabs, crusting around wound, infection, and/or necrosis. The categories mild, moderate, and severe were not mutually exclusive, as respondents could have experienced one or more of the three different ISR categories. Thus, individual patients may be counted in more than one ISR category depending on their individual symptoms.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS, version 17 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Prior to analyses, data were examined for data entry and coding errors. Out-of-range and statistical outliers were also checked and, where possible, corrected. If data could not be corrected, they were treated as missing. Descriptive statistics were generated, including medians, means, standard deviations, minimums, and maximums; categorical variables were expressed as percentages. To assess possible associations between two variables, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for interval data, Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated for ordinal data, and point-biserial correlation coefficients were calculated for dichotomous variables. An independent-sample t test (or its nonparametric counterpart) was used to compare means between two groups, and a dependent-sample t test (or its nonparametric counterpart) was used to compare two means within a group. A one-way analysis of variance test, with or without repeated measures, was used to compare more than two means. Post hoc, pairwise multiple comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni adjustment. Chi-square analysis was used to assess differences in percentages or proportions.20

Results

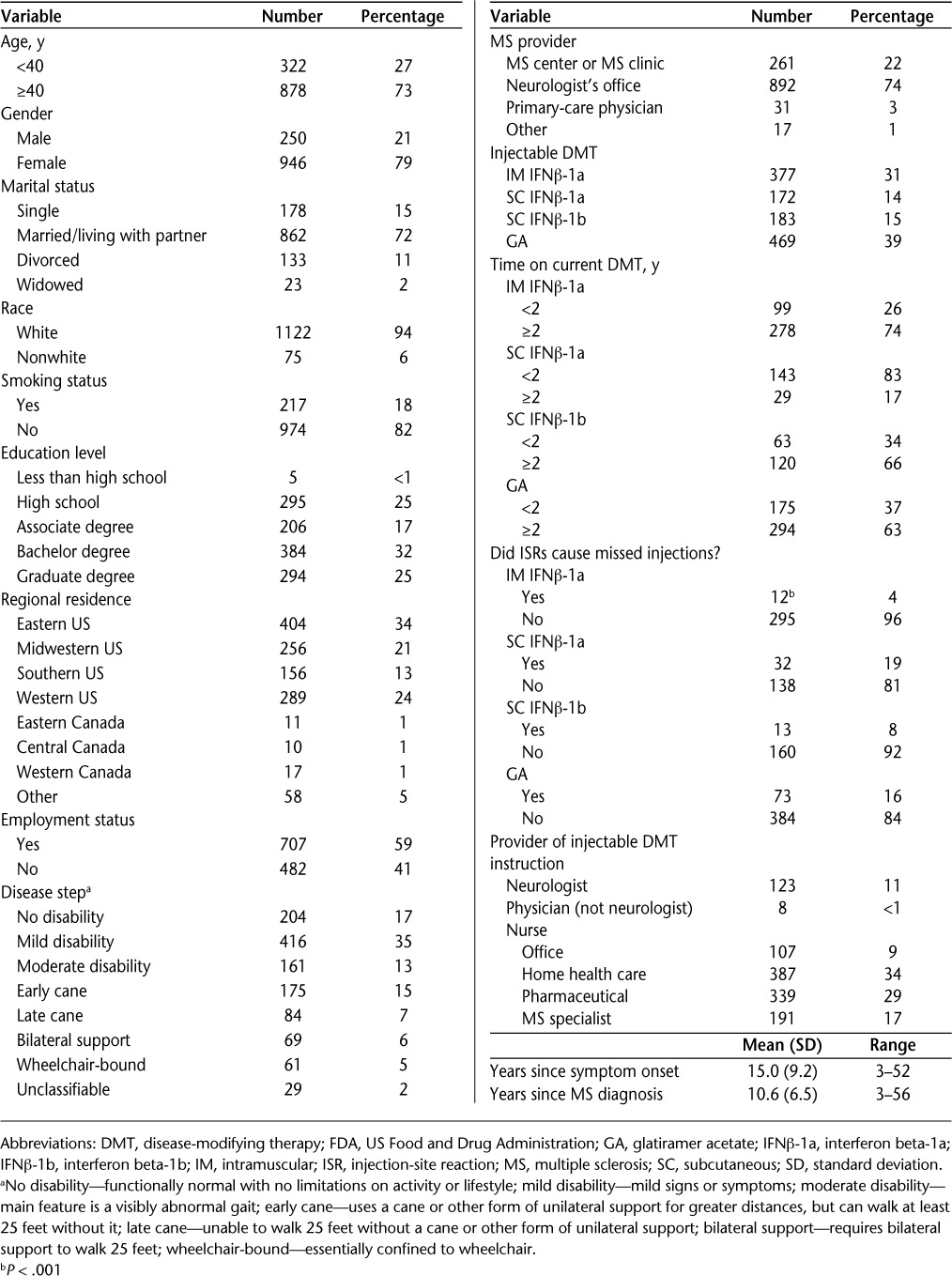

Data for the MS-ISR survey were collected in 2007, with a total of 1380 eligible patients with MS providing responses. However, 179 (13%) respondents did not provide information on DMT use, leaving 1201 responses for analysis. Not all respondents answered all questions; thus, the number of patient responses to each question is a subset of the total number of 1201 useful responses. Patient demographics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics for 1201 respondents using one of the four FDA-approved injectable DMTs

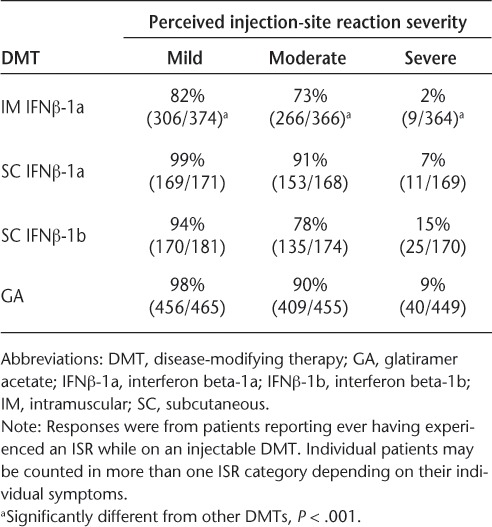

Analysis of patient-reported ISRs showed significant associations between use of injectable DMTs and reports of ISRs, induced discomfort following injection, and severe ISRs (Table 2). Intramuscular IFNβ-1a use was associated with significantly fewer reported ISRs than the other DMTs for all three severity categories, with 82% of patients receiving IM IFNβ-1a experiencing mild side effects (P < .001), 73% experiencing moderate side effects (P < .001), and 2% experiencing severe side effects (P < .001). Also, users of IM IFNβ-1a missed fewer injections because of skin reactions than users of the other DMTs. In comparison, patients receiving SC IFNβ-1a, SC IFNβ-1b, or GA reported a higher incidence of mild (99%, 94%, and 98%, respectively), moderate (91%, 78%, and 90%, respectively), and severe (7%, 15%, and 9%, respectively) ISRs.

Table 2.

Perceived injection-site reaction severity with different DMTs

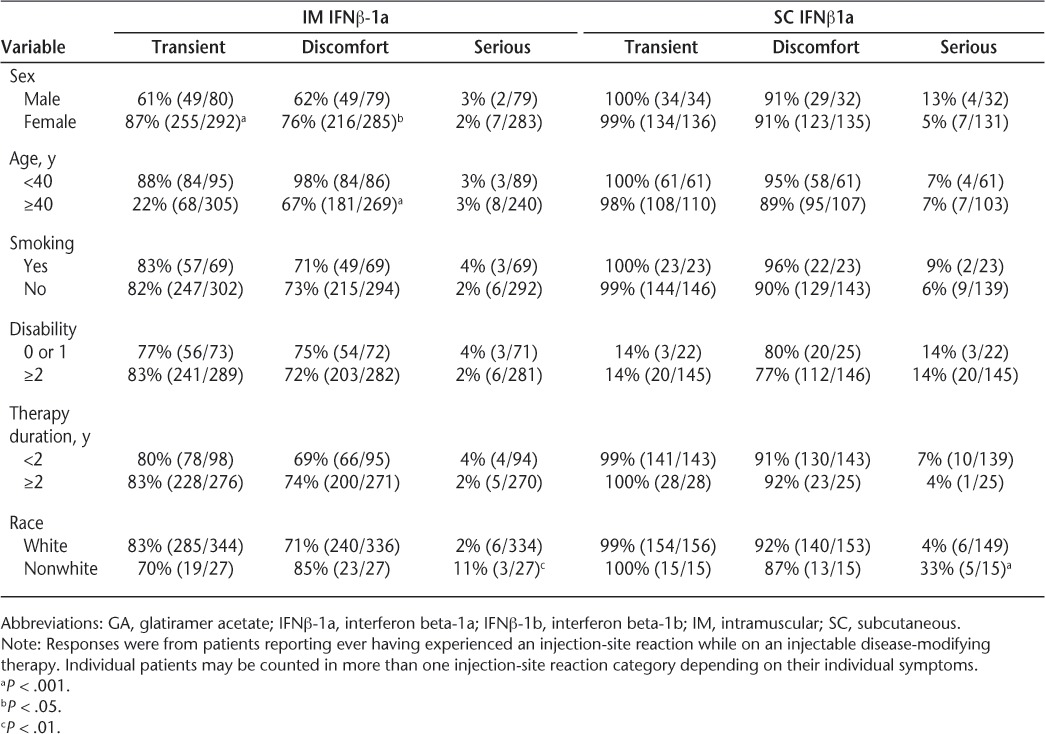

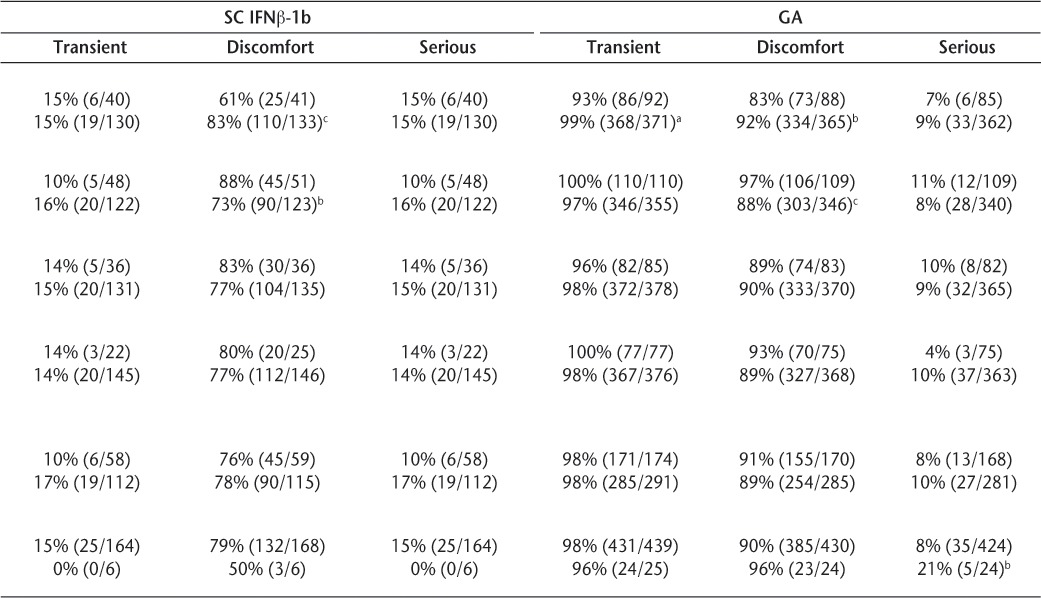

For IM IFNβ-1a, SC IFNβ-1b, and GA, female sex and younger age were significantly associated with moderate ISRs, including perceptions of discomfort. Female users of IM IFNβ-1a and GA reported more transient ISRs than did male users (Table 3). Also, nonwhite patients receiving IM IFNβ-1a, SC IFNβ-1a, and GA reported more severe reactions than whites. Smoking, therapy duration, and disability level were not significantly associated with any category (transient, discomfort-causing, or serious) of skin reactions.

Table 3.

Perceived transient, discomfort-causing, or serious injection-site reactions by select demographic variables

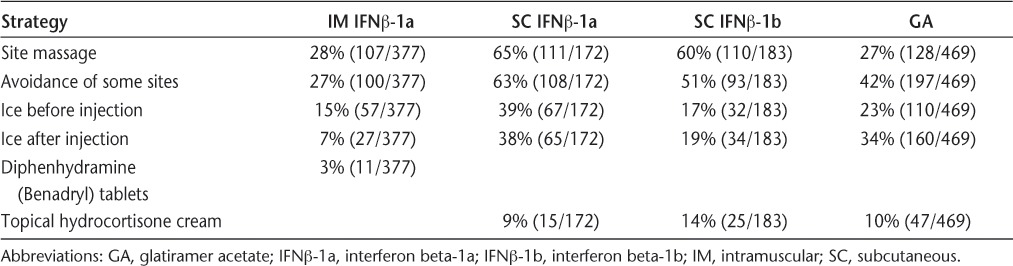

The specific strategies used to manage ISRs were similar among users of each of the four injectable DMTs, with a group of six management strategies constituting the top five strategies for all four injectable DMTs (Table 4). The top two management strategies, injection-site massage and avoidance of sensitive injection sites, were identical across all four injectable DMTs. In addition, of the 55% of all respondents who used SC autoinjectors, 24% reported that autoinjectors ameliorated their ISRs.

Table 4.

Most frequently used strategies to minimize injection-site reactions

Discussion

Multiple studies and clinical experience have demonstrated that ISRs are a common side effect of injectable DMTs.21–23 It is also clear from the present data set and multiple other reported studies that less severe ISRs are reported with IM IFNβ-1a than with the other injectable DMTs for MS.14,24,25 Our findings on the frequency of ISRs (Table 2) generally conform with what has previously been reported and underscore the deleterious effect that ISRs have on treatment continuation and adherence.9,25,26 These data highlight the need for continued study of these side effects and their causes and for continued patient education to alleviate symptoms, maintain compliance, and positively affect long-term MS outcomes.

Regarding associations among demographic characteristics and ISRs, the present results elaborate on previous findings reported by other investigators by identifying new associations and challenging a few previously proposed associations. In accordance with other studies,15,27,28 the present data suggest that females report more moderate ISRs than do males. However, this specific finding was not apparent with SC IFNβ-1a, possibly as the result of a ceiling effect, with a high frequency of moderate side effects being reported by almost all users of that drug. This study also revealed two demographic associations that, to our knowledge, have not been previously reported. First, younger patients (<40 years of age) had more frequent complaints of discomfort with injections. Again, this specific association was not apparent with patients receiving SC IFNβ-1a, possibly because of the higher proportion of patients describing moderate side effects. Second, for every DMT other than SC IFNβ-1b, nonwhites described more severe ISRs than did whites. (Subcutaneous IFNβ-1b may simply be an anomaly because of the small numbers of nonwhite patients receiving this DMT.)

No other significant associations were detected between other recorded demographic variables (tobacco smoking, disability level, or duration of therapy) and perceived ISR severity. Although at least one commentary29 has anecdotally suggested that cigarette smoking concurrent with injectable DMT use may increase ISR severity, neither the present study nor another unpublished analysis30 has confirmed such an association. However, the latter analysis did identify an association between “ever having smoked” and a perceived higher severity of skin reactions to SC DMTs.30 Interestingly, that same analysis also identified an association between increased body-mass index (BMI) and more severe ISRs in response to SC DMTs. Although the present study did not assess BMI, findings on this topic are equivocal, with at least one other report suggesting that BMI might be inversely related to ISR severity.15

It has been suggested that ISRs may become less severe with greater time on therapy.27 This statement is not supported by the present results, which are consistent with reported results from a 4-year study of SC IFNβ-1a in which the percentage of people reporting ISRs did not change over the 4-year study period.31 Recently, Treadaway et al.14 reported that 12% of patients with MS receiving a DMT were nonadherent (having missed more than one injection in the previous 4 weeks) because of concerns about ISRs and pain. Using a similar definition of adherence, the results of the present study were similar, with 11% of patients reporting having missed one or more injections because of ISRs. There were also significant differences between DMT groups in the percentage of patients reporting having missed one or more injections because of ISRs, with IM IFNβ-1a having the fewest (4%) and SC IFNβ-1a having the most (19%) missed injection reports (P < .001) (Table 1).

Several general techniques for mitigating ISRs are recommended to patients with MS who are receiving a DMT. Some techniques—such as use of an autoin-jector,32 EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) cream,33 massage,34,35 and a cooling pack36—are supported by at least small studies. However, evidence in the literature on use of other techniques (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents37 or oral antihistamines38) is either nonsupportive or conflicting. The package inserts for SC IFNβ-1b, SC IFNβ-1a, and GA also recommend injection-site rotation and avoiding reinjection of sites where the skin is red, sore, or damaged.1,3,4 The most frequently reported ISR management techniques in the current study included injection-site massage, site rotation, and the use of cooling techniques and autoinjectors. All other ISR management methods were employed by fewer than 5% of respondents. Widespread use of common clinical injection-site management techniques suggests that patients with MS may generally be receiving instructions on injection techniques and managing ISRs from their prescribers or clinical trainers.

One limitation of this study is that all data were collected by patient self-report, with responses provided by a self-selected group, as noted previously. A substantial proportion of this self-selected group consisted of well-educated, nonsmoking, married white females over 40 years of age, which should be considered when interpreting the results of the study. Having sought out additional Web-based sources of information on MS, this patient cohort may have a more detailed understanding of their disease, what to expect when using injectable DMTs, and ISR prevention and management techniques than the typical person with MS. However, because the current findings are generally consistent with previous reports, we believe that these results accurately represent the general experiences of patients with MS in the real world. In addition, since the time that this survey was conducted, the formulation for SC IFNβ-1a has changed, and the new formulation seems to produce fewer ISRs than the previous formulation, although this difference may depend on the delivery device used.39,40

The present findings reaffirm the importance of patient education on injectable DMT use and ISRs, and also suggest strategies for anticipating which patients may experience more severe ISRs. All patients should receive instruction on strategies for reducing ISR incidence and severity, including education regarding ways to manage side effects, such as site rotation and site massage. Similarly, all patients should be educated about possible severe injection reactions, such as infection and necrosis. Especially when providing anticipatory guidance to patients using SC DMTs and to patients who are female, under the age of 40, and/or nonwhite, it may be important to note that ISRs may be a barrier to adherence.

PracticePoints.

Injection-site reactions (ISRs) are common among users of FDA-approved injectable disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for MS.

Users of the intramuscular agent report fewer ISRs than do users of the subcutaneously (SC) injected therapies.

Patients who use the SC therapies, are under 40 years of age, are female, or are members of a racial minority appear to be more likely to experience bothersome ISRs.

Our findings reaffirm the importance of MS patient education on injectable DMT use and ISRs, and also suggest strategies for anticipating which patients are more likely to experience and to report ISRs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the many people with MS who took time to respond to our survey. They also gratefully acknowledge the support of the staff at the Rocky Mountain MS Center in collecting the data used for this study; the support of Allen Bowling, MD, PhD, Heidi Maloni, PhD, ANP-BC, Margaret O'Leary, RN, MSN, MSCN, and Patricia Kennedy, RN, CNP, MSCN, in developing and reviewing the survey instrument used for this study; and editorial support from Infusion Communications, which was funded by Biogen Idec, Inc.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Mr. Stewart has received speaking honoraria from several companies that manufacture and distribute the injectable MS therapies that are the subject of this study, including Biogen Idec, Inc, and Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by Biogen Idec, Inc, through a grant to the Rocky Mountain MS Center.

References

- 1.Betaseron [package insert] Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avonex [package insert] Cambridge, MA: Biogen Idec, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebif [package insert] Rockland, MA: Serono, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copaxone [package insert] Kfar-Saba, Israel: Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries, Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Extavia [package insert] East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paty DW, Li DK, UBC MS/MRI Study Group and the IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. II. MRI analysis results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993;43:662–667. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1995;45:1268–1276. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.7.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG) Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:285–294. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1998;352:1498–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haas J, Firzlaff M. Twenty-four-month comparison of immunomodula-tory treatments: a retrospective open label study in 308 RRMS patients treated with beta interferons or glatiramer acetate (Copaxone) Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:425–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Rourke KE, Hutchinson M. Stopping beta-interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis: an analysis of stopping patterns. Mult Scler. 2005;11:46–50. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1131oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruggieri RM, Settipani N, Viviano L, et al. Long-term interferon beta treatment for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treadaway K, Cutter G, Salter A, et al. Factors that influence adherence with disease-modifying therapy in MS. J Neurol. 2009;256:568–576. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0096-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lublin FD, Whitaker JN, Eidelman BH, Miller AE, Arnason BG, Burks JS. Management of patients receiving interferon beta-1b for multiple sclerosis: report of a consensus conference. Neurology. 1996;46:12–18. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart T, Tran Z, Bowling A. Factors related to fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2007;9:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart T, Kennedy P, Maloni H, et al. Survey of issues related to injection-site reactions caused by injectable FDA-approved multiple sclerosis medications. Paper presented at: 22nd Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 28–31, 2008; Denver, CO.

- 18.Schwartz CE, Vollmer T, Lee H, North American Research Consortium on Multiple Sclerosis Outcomes Study Group Reliability and validity of two self-report measures of impairment and disability for MS. Neurology. 1999;52:63–70. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohol MJ, Orav EJ, Weiner HL. Disease steps in multiple sclerosis: a simple approach to evaluate disease progression. Neurology. 1995;45:251–255. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wingerchuk DM. Multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies: adverse effect surveillance and management. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6:333–346. doi: 10.1586/14737175.6.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moses H, Jr, Brandes DW. Managing adverse effects of disease-modifying agents used for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2679–2690. doi: 10.1185/03007990802329959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEwan L, Brown J, Poirier J, et al. Best practices in skin care for the multiple sclerosis patient receiving injectable therapies. Int J MS Care. 2010;12:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandes DW, Bigley K, Hornstein W, Cohen H, Au W, Shubin R. Alleviating flu-like symptoms with dose titration and analgesics in MS patients on intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy: a pilot study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:1667–1672. doi: 10.1185/030079907x210741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003;61:551–554. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078885.05053.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samuel L, Lowenstein EJ. Recurrent injection site reactions from inter-feron beta 1-b. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:366–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaines AR, Varricchio F. Interferon beta-1b injection site reactions and necroses. Mult Scler. 1998;4:70–73. doi: 10.1177/135245859800400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frohman EM, Brannon K, Alexander S, et al. Disease modifying agent related skin reactions in multiple sclerosis: prevention, assessment, and management. Mult Scler. 2004;10:302–307. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1002oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conner J. The Effect of Cigarette Smoking and Body Mass Index on Injection Site Reactions in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Cypress, CA: Trident University International; 2008. [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gold R, Rieckmann P, Chang P, Abdalla J. The long-term safety and tolerability of high-dose interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: 4-year data from the PRISMS study. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:649–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brochet B, Lemaire G, Beddiaf A. Reduction of injection site reactions in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients newly started on interferon beta 1b therapy with two different devices [in French] Rev Neurol (Paris). 2006;162:735–740. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(06)75071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuwahara RT, Skinner RB. EMLA versus ice as a topical anesthetic. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:495–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzu N, Ucar H. The effect of cold on the occurrence of bruising, hae-matoma and pain at the injection site in subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarifakioglu N, Sarifakioglu E. Evaluating the effects of ice application on the pain felt during botulinum toxin type-a injections: a prospective, randomized, single-blind controlled trial. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:543–546. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000139563.51598.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauls J. Efficacy of cold for pain: fact or fallacy? Online J Knowl Synth Nurs. 1999;6:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rice GP, Ebers GC, Lublin FD, Knobler RL. Ibuprofen treatment versus gradual introduction of interferon beta-1b in patients with MS. Neurology. 1999;52:1893–1895. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pardo G, Boutwell C, Conner J, Denney D, Oleen-Burkey M. Effect of oral antihistamine on local injection site reactions with self-administered glatiramer acetate. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42:40–46. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181c71ab7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giovannoni G, Barbarash O, Casset-Semanaz F, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a new formulation of interferon beta-1a (Rebif New Formulation) in a phase IIIb study in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: 96-week results. Mult Scler. 2009;15:219–228. doi: 10.1177/1352458508097299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devonshire V, Arbizu T, Borre B, et al. Patient-rated suitability of a novel electronic device for self-injection of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis: an international, single-arm, multicentre, phase IIIb study. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]