Abstract

There is limited clinical evidence on the impact of nurse support and adverse event (AE) mitigation techniques on adherence to interferon beta-1b (IFNβ-1b) therapy in multiple sclerosis (MS) in a real-world setting. The aim of the Success of Titration, analgesics, and BETA nurse support on Acceptance Rates in MS Treatment (START) trial was to assess the combined effect of titration, analgesics, and BETA (Betaseron Education, Training, Assistance) nurse support on adherence to IFNβ-1b therapy in patients with early-onset MS and to evaluate safety. Participants were instructed to titrate IFNβ-1b and use analgesics to minimize flu-like symptoms. All received BETA nurse follow-up at frequent intervals: live training, two telephone calls during the first month of therapy, and monthly calls thereafter. Participants were considered adherent if they took at least 75% of the total prescribed doses over 12 months (≥75% compliance). Safety was monitored via reported AEs and laboratory test results. Participants who took at least one IFNβ-1b dose over 12 months were analyzed (N = 104); 73.8% of participants completed the study. The mean age of participants was 37.2 years; 72.1% were women and 78.8% were white. Ninety participants had relapsing-remitting MS and 14 had clinically isolated syndrome. The mean compliance rate, reported for 96 participants with complete dose interruption records, was 84.4%. At 12 months, 78.1% of participants were considered adherent. The serious adverse event rate was 9.6%; most events were unrelated to therapy. Thus in the START study, in which participants received nursing support combined with dose titration and use of analgesics, the majority of participants were adherent to therapy.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common disabling neurologic disease of young adults. The prevalence of MS in the United States is estimated to be 400,000 people, and about 10,000 new cases are diagnosed every year.1 Introduced in 1993, interferon beta-1b (IFNβ-1b; Betaseron, Bayer HealthCare, Wayne, NJ) was the first immunomodulatory drug capable of modifying the course of MS. Many individuals with MS have benefited from using this injectable medication, which must be taken regularly to achieve optimal outcomes.2 Adverse events (AEs) such as local injection-site pain and reactions, as well as a flu-like syndrome, may prevent some individuals from taking full advantage of IFNβ-1b therapy. However, various measures such as use of analgesic/anti-inflammatory medications, dose-titration schemes, and autoinjectors, along with use of patient support programs, may reduce the incidence and severity of skin reactions and flu-like symptoms, thereby enhancing treatment adherence. A recent study found that individuals with MS who were adherent to IFNβ therapy tended to have a lower risk of relapse, as well as lower risk for an emergency room visit or inpatient admission, than did those who were nonadherent.2 Strategies to improve treatment adherence can help minimize the negative impact of MS on individuals while reducing direct and indirect costs of treating disease exacerbations.

Measures to mitigate AEs and support treatment compliance were used in the BENEFIT (Betaseron®/Betaferon® in Newly Emerging MS for Initial Treatment) study, which evaluated the impact of IFNβ-1b use in patients who were treated early in their disease compared with those who received later treatment. In BENEFIT, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study, 93% of patients who started treatment with IFNβ-1b remained in the trial and completed the study as planned.3 The implementation of a dose-titration scheme at the initiation of therapy, the use of autoinjectors, and co-medication with an analgesic may have contributed to the high patient acceptance rate. However, the BENEFIT study was conducted outside of the United States in a clinical trial setting and used patient support programs specific to local regions.

The primary objective of the Success of Titration, analgesics, and BETA nurse support on Acceptance Rates in MS Treatment (START) study was to assess the combined effect of AE mitigation techniques and nursing support on adherence to IFNβ-1b therapy in a real-world setting in a US population. Nursing support was provided by BETA (Betaseron Education, Training, Assistance) nurses as part of the BETAPLUS MS Support Program (Bayer HealthCare). BETA nurses are certified MS nurses who provide education and support to patients receiving Betaseron. The BETA nurses receive referrals from physicians and, when patients have their medication, provide in-person training in drug reconstitution and self-injection. After training, the BETA nurse makes specific time-sensitive telephone calls to patients for the first 12 months of therapy to provide continuing education and support. A patient may call the BETAPLUS MS Support Program at any time, as a nurse is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. If the nurse determines that a patient or caregiver requires additional training, the BETA nurse can revisit the patient for an additional training session. BETA nurses began providing patient education and training in 1994, shortly after the launch of Betaseron. The BETA Field Nurse Program, launched in 2001, currently has 41 BETA field nurses located throughout the United States, who are supported by 6 telephonic nurses.

The secondary objectives of the START study were to evaluate safety and determine the progression of clinical severity in individuals receiving IFNβ-1b, using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), relapse status, and a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) questionnaire. The study also provided an opportunity to explore the potential importance of cytokine and neurotrophic factors in mediating the clinical effects of IFNβ-1b, and whether these immune parameters could potentially be used as biomarkers or predictors of clinical response to the drug. The results of the exploratory analysis will be reported in a separate publication.4

Methods

Participants

The START trial was a phase 4, open-label, multicenter (33 sites in the United States), prospective, observational, 12-month study designed to evaluate adherence to treatment with IFNβ-1b in individuals with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) with new onset of disease who opted to begin treatment with IFNβ-1b with their physicians' consent. Individuals diagnosed with early-onset RRMS (<12 months since onset) or CIS within 90 days prior to screening were enrolled in the study. Participants had to be between 18 and 50 years of age, with at least two typical MS lesions detected by brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a baseline EDSS score between 0 and 4.0. Participants had to have no cognitive impairment that might prevent their completion of questionnaires over the course of the study and be willing to enroll in the BETAPLUS support program, thereby agreeing to be trained by a BETA nurse and receive follow-up phone calls. Excluded from the study were individuals in whom any disease other than MS could explain neurologic signs and symptoms; those with a diagnosis of primary progressive MS, secondary progressive MS, or progressive relapsing MS, or a diagnosis of RRMS for more than 12 months; and those with complete transverse myelitis or simultaneous onset of bilateral optic neuritis. Also excluded were individuals who had clinically significant heart disease or hepatic, renal, or bone-marrow dysfunction, those with uncontrolled seizure disorder or a history of hypergammaglobulinemia, and those who received immunomodulating or immunosuppressive medications prior to study enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the initiation of any study-specific procedures. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at each site.

Study Design

All participants received IFNβ-1b 250 μg administered subcutaneously every other day. The study drug was obtained by prescription from the treating physician. The study drug was not provided by the sponsor. Each participant was provided with a Betaject 3 (Bayer HealthCare), an automatic injecting device with a 27-gauge needle that does not require calibration prior to study drug administration. Later in the study, the Betaject Lite autoinjector (Bayer HealthCare) was introduced, and participants had the option to switch to this new autoinjector with a thinner (30-gauge) needle or continue using the Betaject 3.

All participants were enrolled in the BETAPLUS Patient Support Program. Each participant received his or her first dose of study drug in the presence of a BETA nurse. During the live training visit, participants were taught to use appropriate injection techniques and were instructed in the use of autoinjectors. All participants received regular contact from a BETA nurse to check his or her progress and to ensure appropriate treatment management—two phone calls within the first month and monthly phone calls thereafter for the full 12 months of the trial.

In order to optimize the tolerability of the study medication, all participants were instructed to titrate the IFNβ-1b dose over a dose-escalation period of 7+ weeks beginning at the start of treatment until they reached the full dose of 250 μg. The participants initially received 25% of the full dose (0.25 mL) during weeks 1 to 2 of treatment, followed by 50% of the full dose (0.5 mL) during weeks 3 to 4, 75% of the full dose (0.75 mL) during weeks 5 to 6, and finally the full dose (1.0 mL) during week 7 and thereafter. For the first 3 months of the study, all participants were instructed to take analgesic/nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 30 minutes before injection to help minimize flu-like symptoms. Additional anti-inflammatory medication was allowed during or beyond the first 3 months of treatment if deemed necessary by the treating physician for relief of expected interferon-related flu-like symptoms. Steroid treatment for the first clinical demyelinating event and/or subsequent relapses was permitted at the discretion of the treating physician. However, if a participant was or had been on systemic steroids, a 2-week washout period must have taken place before study entry and baseline assessments. Participants were encouraged to use either ice packs or warm packs immediately before and after the administration of the study drug. During all contacts, participants were queried about study drug compliance; as part of their regular duties, the BETA nurses stressed the importance of study drug compliance.

Study Endpoints and Procedures

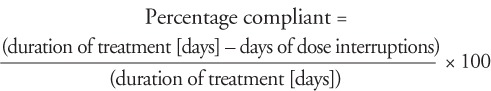

The primary efficacy variable was the rate of adherence to treatment with IFNβ-1b, as reported by the participant. Adherence was defined in terms of percentage compliant with prescribed IFNβ-1b treatment. Compliance was calculated using the following formula:

|

Participants were considered adherent to IFNβ-1b treatment if they took at least 75% of total prescribed doses over the study period. Participants who had taken less than 75% of total prescribed IFNβ-1b doses were considered nonadherent. Compliance information was obtained from participant self-reporting and recorded by the investigator during visits at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. Based on the investigator's assessment, the proportion of participants who were adherent (had taken ≥75% of total prescribed IFNβ-1b doses over the study period) was summarized. Participants with partial or missing dates of dose interruptions were excluded from the calculations.

The secondary efficacy variables included clinical outcomes, which were based on EDSS progression and relapse history during the treatment period. EDSS assessments were performed at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months. EDSS progression was defined as having an increase of 1.0 point or more in EDSS score over a baseline value at any time up to month 12.

Relapse assessments were performed at baseline and at 3, 6, and 12 months and whenever necessary. All of the following criteria had to be met for a relapse to be established: neurologic abnormality separated by at least 30 days from onset of a preceding clinical event and lasting for at least 24 hours; absence of fever or known infection; and objective neurologic impairment, correlating with the participant's reported symptoms, defined as either an increase in at least one of the functional systems of the EDSS score or an increase in the total EDSS score.

A questionnaire that assessed HRQOL, the Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS), was completed by each participant at the study site at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. The response period was the prior 7 days. The FAMS questionnaire consists of 58 items on 7 subscales (mobility, symptoms, emotional well-being, general contentment, thinking/fatigue, family/social well-being, and additional concerns); a higher score reflects a higher quality of life. To generate a valid FAMS score, at least 50% of all items within each domain must have been answered and at least 80% of total items must have been answered. The minimum important difference (MID) in median FAMS total score change is believed to be a change of 4 points. Therefore, the participants falling into three groups (improved, ≥4 points; same, between −4 and +4; worsened, ≤−4) were summarized for 6 and 12 months based on FAMS total score only.

Adverse events (AEs) were assessed and reported at each visit (scheduled and unscheduled) by the treating physicians. Clinical laboratory assessments including complete blood count with differential and platelet count and chemistry panel (creatinine, total bilirubin, and liver transaminase tests) were performed at baseline and at 3 and 12 months, and were evaluated by a central laboratory.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics for treatment duration and compliance rates were reported. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for the adherence rate. The proportion of participants who remained free of EDSS progression or free of relapses was analyzed using the Fisher exact test. The P value compared the proportion of participants who remained free of EDSS progression or relapses between the CIS and RRMS groups.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Of the 107 enrolled participants, 104 (97.2%) were treated with at least one dose of IFNβ-1b over the 12-month period and made up the efficacy and safety analyses set; 79 (73.8%) of the enrolled participants completed the study to month 12. For the 25 participants who discontinued the study early, the reasons included withdrawal of consent (4 participants), loss to follow-up (4 participants), AE (8 participants), physician decision (3 participants), pregnancy (2 participants), protocol deviation (1 participant), and other, which included family issues (1 participant), multiple appointments missed (1 participant), and moving (1 participant).

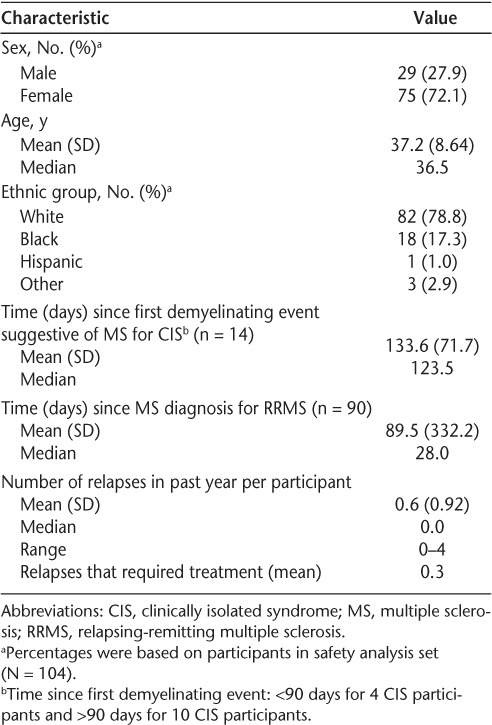

Most participants were women (72.1%), and the mean age was 37.2 years. Most were white (78.8%); 17.3% were black (Table 1). The majority of treated participants (86.5%) were diagnosed with RRMS, and 41.3% had at least one relapse within the year preceding enrollment; steroid treatment was required for 28.8%. Most patients (97.1%) did not have ongoing relapses at study entry.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants

Adherence to IFNβ-1b Treatment

Percentage Compliant with Treatment

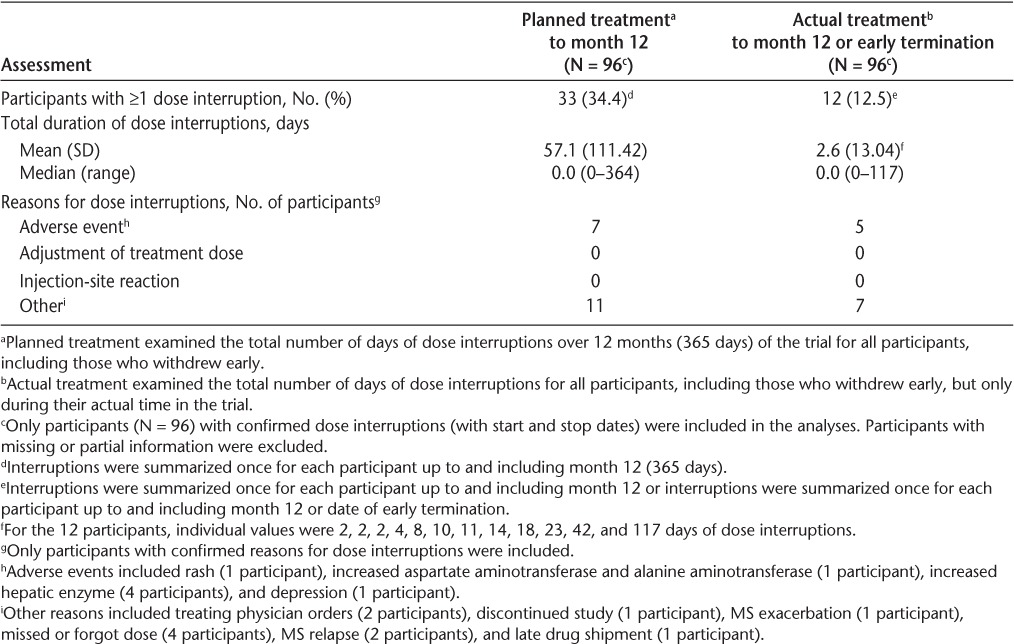

Of the 104 participants, 96 had complete dose interruption records from the start of the study, including those who withdrew early and did not complete the 12-month study. These participants made up the analysis set. Because participants who discontinued the study were included in the analysis, the mean compliance rate for the 96 participants was calculated in two ways: by planned treatment (examining the total number of days of dose interruptions over 12 months [365 days] of the trial for all participants, including those who withdrew early) and by actual treatment (examining the total number of days of dose interruptions for all participants, including those who withdrew early, but only during their actual time in the trial).

An analysis of dose interruptions based on planned treatment showed that 33 participants (34.4%) had at least one dose interruption to month 12, yielding a mean (SD) of 57.1 (111.42) days of dose interruptions (Table 2). An analysis of dose interruptions based on actual treatment showed that 12 participants had at least one dose interruption day (individually of 2, 2, 2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 14, 18, 23, 42, and 117 days) to month 12 or early termination, yielding a mean of 2.6 (13.04) days of dose interruptions. No participant missed a prescribed IFNβ-1b dose because of an injection-site reaction or needed a dose adjustment. A dose interruption due to an AE was reported in 7 patients.

Table 2.

Dose interruptions

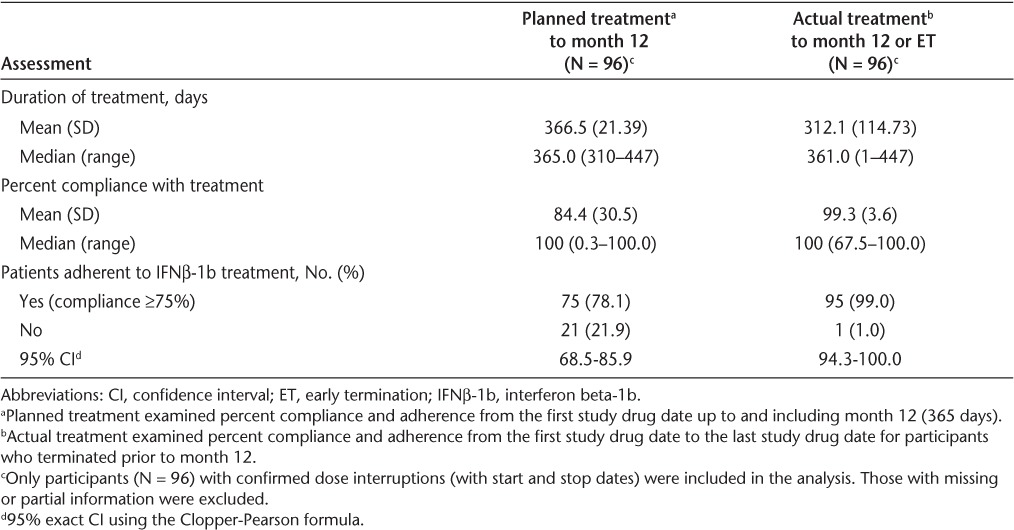

When based on planned treatment, the mean compliance rate was 84.4% (median, 100%). When based on actual treatment, the mean compliance rate was 99.3% (median, 100%) (Table 3). Although 79 (73.8%) participants completed the 12-month study, percent compliance with prescribed IFNβ-1b doses was determined for 96 (92.3%) participants, thus accounting for the high compliance rate.

Table 3.

Percent compliance and adherence to treatment

Percentage Adherent to Treatment

Adherence to IFNβ-1b treatment was the primary efficacy variable. Participants with a compliance rate of at least 75% were considered adherent to IFNβ-1b treatment. Based on planned treatment up to month 12, 78.1% (95% CI, 68.5–85.9) of participants were considered adherent to IFNβ-1b treatment (Table 3). Based on actual treatment up to month 12 or early termination, 99% (95% CI, 94.3–100.0) of participants were considered adherent to IFNβ-1b treatment.

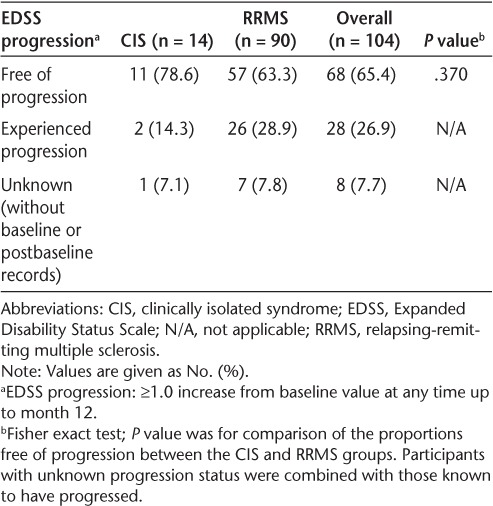

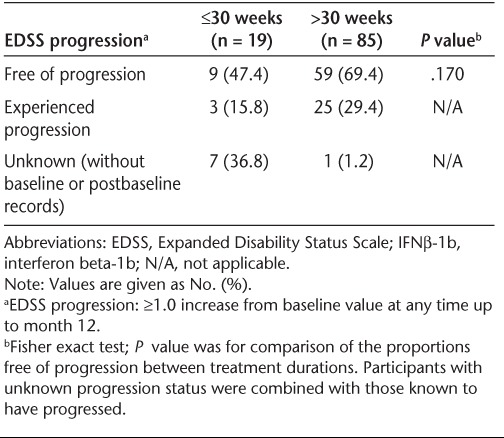

EDSS Progression

Of the 104 participants, 65.4% were free of EDSS progression to month 12 (Table 4). There was no statistically significant difference in freedom from EDSS progression by baseline disease status (78.6% of CIS participants vs. 63.3% of RRMS participants; P = .370). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in freedom from EDSS progression to month 12 when analyzed by median duration (51.5 weeks) of treatment (58.5% in the ≤51.5 weeks subgroup vs. 72.5% in the >51.5 weeks subgroup; P = .153). One potential explanation for this lack of difference is that the majority of participants in the RRMS group had very early disease (<1 year); differences between the RRMS and CIS subgroups might not have been observed at this early stage. Similarly, in post hoc analyses, there was no statistically significant difference in freedom from EDSS progression to month 12 when the duration of treatment analyzed was 30 weeks or less versus more than 30 weeks (47.4% in the ≤30 weeks subgroup vs. 69.4% in the >30 weeks subgroup; P = .170) (Table 5). Because most of the participants with unknown EDSS progression records were in the 30 weeks or less subgroup, interpretation of the percentage differences of participants who had progressed is difficult.

Table 4.

EDSS progression over the 12-month study period by baseline disease

Table 5.

EDSS progression over the 12-month study period by duration of IFNβ-1b treatment

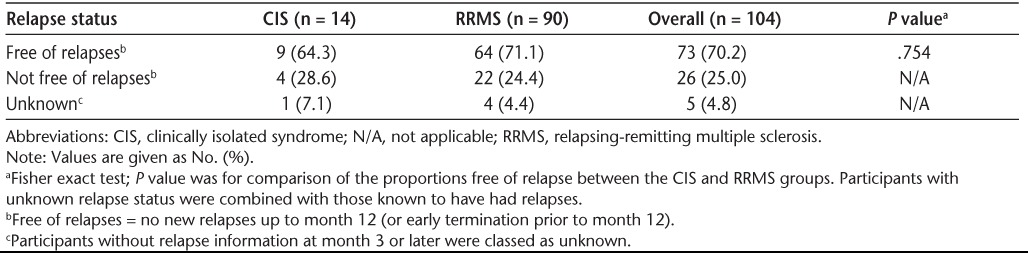

Relapse Rate

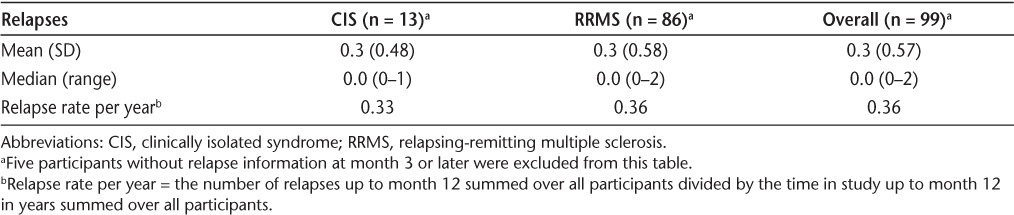

At month 12, 70.2% of participants were relapse-free; there was no statistically significant difference in relapse-free status between participants with CIS versus RRMS (P = .754) (Table 6). With IFNβ-1b treatment, the mean number of relapses at month 12 per participant was 0.3; the maximum number of relapses per participant was 1 in the CIS group and 2 in the RRMS group. At baseline, the mean yearly relapse rate was 0.6. At month 12, the mean relapse rate was 0.33 in the CIS group, 0.36 in the RRMS group, and 0.36 overall, a 40% reduction from baseline (Table 7). Approximately 70% of participants were relapse-free at month 12, regardless of the duration of IFNβ-1b treatment, when a median cutoff of 51.5 weeks was applied.

Table 6.

Relapse status over the 12-month study period by baseline disease

Table 7.

Total number of relapses per participant

Health-Related Quality of Life

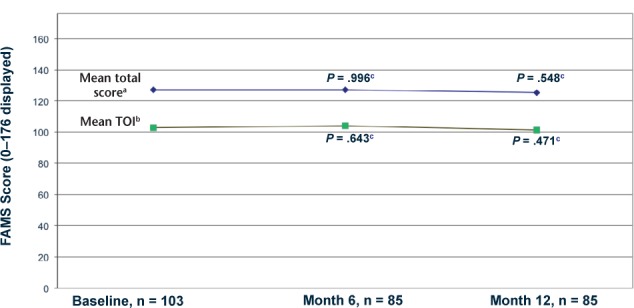

The FAMS questionnaire total score was calculated by summing domain subscores from six of the seven domains (mobility, symptoms, emotional well-being, general contentment, thinking/fatigue, family/social well-being), excluding the additional concerns domain. The FAMS scores were high at baseline, and there was very little mean change from baseline in the FAMS total score at 6 and 12 months (Figure 1). As for change in status based on the FAMS total score at month 6, 47.6% of participants improved, 16.7% showed no change, and 35.7% worsened. At month 12, 40.5% of participants improved, 19.0% showed no change, and 40.5% worsened. An additional assessment was performed using the FAMS Trial Outcome Index (FAMS-TOI), calculated by summing domain subscores from five of the seven domains (mobility, symptoms, general contentment, thinking/fatigue, and additional concerns). Similarly, there was little mean change from baseline in the FAMS-TOI at 6 and 12 months (Figure 1). None of the changes from baseline in the FAMS total score or the FAMS-TOI was statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Functional Assessment of Multiple Sclerosis (FAMS): total score and Trial Outcome Index (TOI)

aTotal score = sum of 6 of 7 domains (excluding additional concerns); scale 0–176.

bTOI = sum of 5 domains; scale 0–148.

cChange from baseline P value by Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Note: To be valid for analysis, at least 50% of the items in each domain must have been answered and at least 80% of items overall.

Adverse Events

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 73.1% of participants over the course of the study. The most common (≥5%) TEAEs were general symptoms and administration-site reactions, reported in 65.4% of participants, followed by nervous system disorders, reported in 46.2% of participants. The most frequently reported TEAEs—anticipated as a result of IFNβ-1b—were flu-like illness (29.8%), fatigue (26.0%), injection-site reaction (21.2%), and headache (17.3%). The TEAEs judged by the investigator as definitely related to the study drug were flu-like illness and events associated with the injection of the study drug, including injection-site reaction, injection-site pain, and injection-site erythema. Most TEAEs were considered of mild (26.0%) or moderate (54.8%) intensity; only 11.5% were considered of severe intensity.

A total of 8 participants experienced TEAEs that led to IFNβ-1b withdrawal. These TEAEs included psychiatric disorders in 3 participants, with depression in 2 of these participants and panic attack in the other participant. Other TEAEs that led to IFNβ-1b discontinuation were reported in 1 participant each and included fatigue, pyrexia, pain, injection-site hematoma, dizziness, lumbar radiculopathy, and abnormal hepatic function (due to transaminase elevation at month 12). Hematology laboratory results and vital sign results revealed no clinical concerns. A total of 9 participants experienced TEAEs in chemistry laboratory values as follows: increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT; 4 participants); increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST; 3 participants); increased hepatic enzyme (4 participants) (the numbers of participants do not add up to 9 because of the presence of multiple abnormal values in the same patient). There were no reports of abnormal total bilirubin as a laboratory value or TEAE.

Serious Adverse Events

Of the 104 participants, 10 (9.6%) experienced at least one serious AE (SAE). Two participants (1.9%) were reported with MS relapse. Other SAEs, reported in 1 participant each, did not conform to a particular pattern. One of 3 participants who became pregnant during the study experienced a breech birth, recorded as an SAE. There were no deaths during the study.

Impact of Needle Gauge on Participant Adherence to Therapy

Because AE mitigation techniques were an important aspect of this study, the impact of needle gauge on participant adherence to therapy was evaluated in a post hoc analysis. About 1.5 years after study enrollment began, a protocol amendment instituted a switch from use of a 27-gauge needle to use of a 30-gauge needle for IFNβ-1b injections (Betaject Lite autoinjectors). Participants were not required to switch, but new autoinjectors were provided to those receiving refills after November 2008. The needle gauge change was rolled out in phases and was monitored by BETA nurses rather than the study team. Of the 104 participants in the study, 53 used the 27-gauge needle only and 51 changed from a 27– to a 30-gauge needle. When adherence rates in participants (planned treatment cohort) using the 27-gauge needle for all injections compared with those of participants who switched from 27- to 30-gauge needles were analyzed retrospectively, a statistically significant difference was found (56.5% [26/46] for those using the 27-gauge needle vs. 98.0% [49/50] for those who switched; P < .001). For actual treatment, there was no statistically significant difference in adherence rates (100.0% [46/46] for those using the 27-gauge needle vs. 98.0% [49/50] for those who switched).

Interpretations drawn from these results should be made with caution. Participants who dropped out while using the 27-gauge needle may have been nonadherent to treatment. The remainder of participants who switched were in the study before the needle-gauge change with high compliance, and either continued as such with the needle-gauge change or still dropped out, but with sufficient compliance to remain adherent. When adherence was analyzed retrospectively by the use of analgesics or NSAIDs, newly starting (after initiating IFNβ-1b dosing) the concomitant use of analgesics or NSAIDs did not have an effect on the duration of treatment, percent compliant, or adherence rate in this study. It appears that the total intervention—consisting of dose titration, the use of analgesics, and enhanced BETA nurse support—had a positive impact on participant adherence to treatment over the study period, rather than any single technique.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the combined effect of AE mitigation techniques, such as dose titration and use of analgesics, and nurse support in improving treatment adherence and allowing patients to realize the benefits of IFNβ-1b therapy. Because patients may experience injection anxiety and difficulty managing self-care, the training and support offered by BETA nurses can also provide patients with encouragement, comfort, and confidence in self-injection that may contribute to improved adherence.

In START, the adherence rate to IFNβ-1b treatment, based on planned treatment (365 days), was 78.1%. When the analysis was based on actual treatment records, 99% of all participants were adherent to IFNβ-1b treatment. Comparison of these adherence results directly with those of previous studies may not be appropriate, since adherence may have been evaluated or calculated differently in a different sample set. In this study, IFNβ-1b use was participant-reported and not determined from prescription or drug accountability records. In clinical trials among people with chronic conditions such as MS, adherence rates can be markedly high because of the selection of patients and the attention they receive; yet the reported average adherence rates range from 43% to 78%.5

The demographic and baseline disease characterization of participants in START was, in part, typical for a target population with MS. Although most participants were white (78.8%), there were more black participants (17.3%) than in previous studies, in which white participants made up 93% to 98% of the IFNβ-1b treatment group.3,6

In the START trial, 65.4% of participants were free of EDSS progression to month 12. No statistically significant difference was found in freedom from EDSS progression to month 12 by baseline disease status (CIS vs. RRMS). A majority of participants (70.2%) were relapse-free at month 12. No statistically significant difference was found in relapse-free status by disease status (CIS vs. RRMS). Possible explanations for this lack of a difference are the small number of CIS patients and the very early disease stage of the RRMS group.

For the HRQOL outcome, the FAMS scores were high at baseline. There was very little mean change in the FAMS total score and FAMS-TOI over the course of the study (when evaluated by participants at months 6 and 12), which indicates stability of the disease course from the participants' perspective with IFNβ-1b treatment. None of the changes from baseline in FAMS total score or TOI were statistically significant.

The safety profile of IFNβ-1b in this 12-month study was consistent with that observed in previous studies of IFNβ-1b treatment in people with MS.3,6–8 The most frequently reported TEAEs, which were anticipated as a result of IFNβ-1b administration, were flu-like illness, fatigue, and injection-site reaction. The frequencies of these events were similar to those reported in previous studies, in which flu-like illness was reported in 40%6 and 31.9%9 of participants, fatigue was reported in 22%,6 and injection-site reactions were reported in 22%.6 No unusual patterns for TEAE intensity (mild in 26.0% of participants and moderate in 54.8% of participants) or relationship to IFNβ-1b (definitely related in 36.5% of participants and probably related in 24.0% of participants) were observed. In addition, neither skin necrosis nor suicide was reported for any participant in this study. Of note, fatigue had been reported as a baseline symptom or condition in 13.5% of participants and was reported as an increasing or worsening TEAE in 0.5% of participants. Psychiatric disorder had been reported as a baseline symptom or condition in 36.5% of subjects, with depression reported in 25.0%. Depression was an increased or exacerbated TEAE in 0.3% of participants. Chemistry and hematology laboratory results and vital signs results were in line with results in other recent studies.9

The positive effect of BETA nurse support, combined with dose titration and the use of analgesics, is reflected in the high adherence rates observed in this study. The study sample was too small to identify any subgroups who are at higher risk for nonadherence and/or AEs. Adverse events are one of the primary reasons for nonadherence in patients with MS receiving long-term treatment with interferon therapy. In a review of MS studies on compliance during long-term IFNβ treatment, the percentage of participants who stopped treatment ranged from 17% to 41%, with AEs reported as a major cause of nonadherence.10–15 As these findings suggest, AEs are a major barrier to treatment adherence.

Management strategies for the common side effects associated with MS therapy, such as injection-site reactions, headache, and flu-like symptoms, are critical to maximize patient compliance with long-term IFNβtreatment.16 In this study, various strategies including the gradual titration of the IFNβ-1b dose over a dose-escalation period of 7+ weeks initiated at the start of treatment and the use of analgesics/anti-inflammatory medications were implemented to help reduce the symptoms associated with the use of IFNβ therapy and promote adherence.

In addition to proactive side-effect management techniques, there is a need for strategies to deal with other factors that may contribute to nonadherence, including injection anxiety17,18 and difficulty managing self-care.19 Because nurses are the health-care professionals most often responsible for training MS patients in self-injection techniques and monitoring their compliance, the START study included BETA nurse support. The training in self-administration of IFNβ-1b, reimbursement assistance, educational materials, and follow-up support offered by BETA nurses provided participants with encouragement, comfort, and confidence in self-injection that may have contributed to the high compliance rate observed in this study and are factors known to improve adherence.20,21

Efforts to enhance treatment adherence optimize efficacy and allow patients to realize the benefits of therapy.22 The positive impact of adherence to 12 months of IFNβ-1b therapy was reflected in the START study clinical outcomes. The EDSS scores, the EDSS progression-free status, the relapse-free status, and FAMS scores all showed stable disease, or a disease status, similar to that observed with IFNβ-1b treatment of MS in other clinical trials.3,6–8

The impact of adherence to IFNβ treatment on clinical outcomes in a real-world setting was also explored in a retrospective study using a database that includes both pharmacy and medical claims data from individuals with MS (N = 1606) receiving IFNβ therapies over a 3-year period, from 2006 to 2008.2 During the study period, the average medication possession ratio (MPR) for all participants on IFNβ therapy ranged from 72% to 76%. The MPR used in this study was similar to our planned treatment definition, using a fixed-interval (360 days) compliance calculation and applying a cutoff compliance point for adherence to therapy. Participant adherence, defined as an MPR of at least 85% in any given year, ranged from 27% to 41%; only 4% of participants had an MPR of at least 85% throughout the 3-year study period. In addition, participants who were adherent to IFNβ treatment tended to have a lower risk of relapse and lower risk for an emergency room visit or inpatient admission than nonadherent participants. These findings provide evidence of the importance of treatment adherence and its impact on relapse and health-care resource utilization. Clearly, measures to improve adherence to IFNβ treatment should be implemented to enable individuals with MS to achieve optimal outcomes and reduce unnecessary health-care costs.

START was an observational study; therefore, the lack of comparative arms limits the interpretation to the combined effect of titration, use of analgesics, and nursing support on adherence to treatment with IFNβ-1b. However, the study documents adherence to IFNβ-1b treatment in a real-world setting, using 12-month support from BETA nurses combined with measures to mitigate AEs.

In conclusion, in the START study, the majority (78.1%) of participants who received BETA nurse support combined with dose titration and use of analgesics were adherent to 12 months of IFNβ-1b therapy; the mean compliance rate was 84.4%. The study findings indicate a safety profile of IFNβ-1b consistent with what has been reported in other clinical trials. Improving adherence to treatment has the potential to minimize the relapse rate and reduce health-care resource utilization in people with MS.

PracticePoints.

Adverse events have been found to be a major barrier to treatment adherence in MS.

Adverse event mitigation techniques, such as dose titration and use of analgesics, combined with nursing support can improve treatment adherence and allow MS patients to realize the benefits of interferon beta-1b therapy.

The training and support offered by BETA (Betaseron Education, Training, Assistance) nurses can help patients manage self-care and reduce injection anxiety, possibly contributing to improved adherence.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Margaret Callahan, MS, of Precept Medical Communications, Warren, New Jersey, and was funded by Bayer HealthCare.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Dhib-Jalbut has received grants for clinical research from Bayer HealthCare, Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, and Teva Neuroscience. In addition, he has served as an advisor or consultant for Bayer HealthCare, Merck Serono, Biogen Idec, and Teva Neuroscience. Dr. Markowitz has conducted research with Bayer HealthCare, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, EMD Serono, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical Co, and Biogen Idec. In addition, he has served as a consultant for Bayer HealthCare, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, EMD Serono, Novartis, Biogen Idec, Sanofi-Aventis, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Patel has been a salaried employee of Bayer HealthCare and Rutgers University. Drs. Boateng and Rametta are salaried employees of Bayer HealthCare.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by Bayer HealthCare.

References

- 1.National Multiple Sclerosis Society. About MS. What we know about MS. Who gets MS? National Multiple Sclerosis Society Web site. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/index.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2012.

- 2.Steinberg SC,, Faris RJ,, Chang CF,, Chan A,, Tankersley MA. Impact of adherence to interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: a non-experimental, retrospective, cohort study. Clin Drug Investig. 2010;30:89–100. doi: 10.2165/11533330-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappos L,, Polman CH,, Freedman MS, Treatment with interferon beta-1b delays conversion to clinically definite and McDonald MS in patients with clinically isolated syndromes. Neurology. 2006;67:1242–1249. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237641.33768.8d. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhib-Jalbut S,, Sumandeep S,, Valenzuela R,, Ito K,, Patel P,, Rametta M. Immune response during interferon beta-1b treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis who experienced relapses and those who were relapse-free in the (Success of Titration, analgesics, and BETA nurse support on Acceptance Rates to early MS Treatment with Betaseron) START Study. J Neuroimmunol. 2012 Sep 18;pii(12):S0165–5728. 00268-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.08.012. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.08.012. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterberg L,, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Connor P,, Filippi M,, Arnason B, 250 microg or 500 microg interferon beta-1b versus 20 mg glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:889–897. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70226-1. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kappos L,, Freedman MS,, Polman CH, Long-term effect of early treatment with interferon beta-1b after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: 5-year active treatment extension of the phase 3 BENEFIT trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:987–997. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70237-6. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Betaseron [package insert] Wayne, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reder AT,, Ebers GC,, Traboulsee A, Cross-sectional study assessing long-term safety of interferon-beta-1b for relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology. 2010;74:1877–1885. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e240d0. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clerico M,, Barbero P,, Contessa G,, Ferrero C,, Durelli L. Adherence to interferon-beta treatment and results of therapy switching. J Neurol Sci. 2007;259:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milanese C,, La ML,, Palumbo R, A post-marketing study on interferon beta 1b and 1a treatment in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: different response in drop-outs and treated patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1689–1692. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.12.1689. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruggieri RM,, Settipani N,, Viviano L, Long-term interferon-beta treatment for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:361–364. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0190-3. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tremlett HL,, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology. 2003;61:551–554. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078885.05053.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rio J,, Porcel J,, Tellez N, Factors related with treatment adherence to interferon beta and glatiramer acetate therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11:306–309. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1173oa. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Rourke KE,, Hutchinson M. Stopping beta-interferon therapy in multiple sclerosis: an analysis of stopping patterns. Mult Scler. 2005;11:46–50. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1131oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langer-Gould A,, Moses HH,, Murray TJ. Strategies for managing the side effects of treatments for multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;63:S35–S41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.11_suppl_5.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox D,, Stone J. Managing self-injection difficulties in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2006;38:167–171. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohr DC,, Boudewyn AC,, Likosky W,, Levine E,, Goodkin DE. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:125–132. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser C,, Morgante L,, Hadjimichael O,, Vollmer T. A prospective study of adherence to glatiramer acetate in individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2004;36:120–129. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saunders C,, Caon C,, Smrtka J,, Shoemaker J. Factors that influence adherence and strategies to maintain adherence to injected therapies for patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42:S10–S18. doi: 10.1097/jnn.0b013e3181ee122b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lugaresi A. Addressing the need for increased adherence to multiple sclerosis therapy: can delivery technology enhance patient motivation? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6:995–1002. doi: 10.1517/17425240903134769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girouard N,, Theoret G. Management strategies for improving the tolerability of interferons in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;30:18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]