Abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus is the predominant airborne fungal pathogen in immunocompromised patients. Genetic defects in NADPH oxidase (chronic granulomatous disease; CGD) and corticosteroid-induced immunosupression lead to impaired killing of A. fumigatus and unique susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis via incompletely characterized mechanisms. Recent studies link Toll-like receptor activation with phagosome maturation via the engagement of autophagy proteins. Herein, we found that infection of human monocytes with A. fumigatus spores triggered selective recruitment of the autophagy protein LC3 II in phagosomes upon fungal cell wall swelling. This response was induced by surface exposure of immunostimulatory β-glucans and was mediated by activation of the Dectin-1 receptor. LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus-phagosomes required syk kinase-dependent production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and was nearly absent in monocytes of patients with CGD. This pathway was important for control of intracellular fungal growth, as silencing of Atg5 resulted in impaired phagosome maturation and killing of A. fumigatus. In-vivo and ex-vivo administration of corticosteroids blocked LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes via rapid inhibition of syk kinase phosphorylation and downstream production of ROS. Our studies link Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling with maturation of A. fumigatus phagosomes and uncover a mechanism for development of invasive fungal disease.

Keywords: Autophagy, Aspergillus fumigatus, Dectin-1, β-glucan, syk, corticosteroids

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus fumigatus, a ubiquitous saprophytic mold, is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients1. Acquired quantitative and qualitative innate immune defects, typically encountered in hematological malignancy patients with severe chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and recipients of transplants following treatment with high doses of corticosteroids, are major predisposing factors for development of invasive aspergillosis1–3. A. fumigatus is currently regarded as an emerging fungal pathogen in a broad range of non-neutropenic hosts who receive prolonged courses of corticosteroid therapy4, including patients with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, and prolonged stay in intensive care units1,4–6. Moreover, patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a rare primary immunodeficiency characterized by genetic defects in NADPH oxidase complex, are uniquely susceptible for development of invasive aspergillosis1,2.

Although risk factors for development of invasive aspergillosis are well characterized, the immunopathogenesis of this frequently lethal opportunistic mycosis is incompletely understood. In immunocompetent individuals, professional phagocytes, including resident alveolar macrophages, circulating monocytes, and neutrophils, efficiently eliminate A. fumigatus spores, which are inhaled in a daily basis, to prevent germination of spores to hyphae and development of invasive fungal disease1,2,7,8. A. fumigatus spores are degraded within acidified lysosomal compartments of human phagocytes via the complex process of phagolysosomal fusion9,10. Genetic defects in NADPH oxidase-derived ROS generation and corticosteroid therapy are associated with impaired maturation of A. fumigatus phagosomes and attenuated fungal killing, via incompletely characterized mechanisms11–13.

The past few years have witnessed major advances in understanding innate sensing of fungi. Initial studies demonstrated that A. fumigatus preferentially activates Toll like receptors (TLR)-2 and TLR-4, and results in NF-κB mediated immune responses14,15. Recent evidence suggests an emerging role for Dectin-1 and other C-type lectin receptors in antifungal immunity16–21. Dectin-1 recognizes β-glucan carbohydrates in the fungal cell walls and triggers intracellular signaling via a cytoplasmic ITAM-like motif via recruitment of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and Raf-1 kinase16,22.

In contrast to the well-characterized role of pattern recognition receptors in activating signaling pathways for induction of cytokine release, their contribution in phagosome maturation is less well defined. Recently, the recruitment of proteins of the autophagy machinery, including LC3 II, Atg5, and Atg7, in phagosomes containing microbial ligands in response to TLR activation was found to be important for phagolysosomal fusion and pathogen elimination by murine macrophages23. Although the signaling regulating autophagy protein recruitment in TLR containing phagosomes has not been characterized, this response was shown to be dependent on NADPH-derived ROS production24. At present, there is no clear evidence on whether and how innate sensing of A. fumigatus is linked to phagosome maturation and killing by professional phagocytes.

Herein, we found that A. fumigatus infection of human monocytes triggered a selective recruitment of LC3 II autophagy protein in phagosomes upon fungal cell wall swelling. This response was induced by surface exposure of immunostimulatory β-glucans and required activation of Dectin-1 receptor. LC3 II recruitment in Aspergillus phagosomes was independent of raf-1 kinase signaling, but required syk kinase-mediated ROS production and it was nearly absent in monocytes of patients with CGD. This pathway was important for fungal clearance because conditional inactivation of Atg5 resulted in attenuated phagolysosomal fusion and killing of A. fumigatus spores. Importantly, in-vivo administration of corticosteroids in patients with rheumatologic diseases or ex-vivo treatment of human monocytes with hydrocortisone blocked LC3 II recruitment in Aspergillus-containing phagosomes via rapid inhibition of phosphorylation of syk kinase and downstream ROS production. Overall, our studies link Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling with phagosome maturation and uncover a potential target for development of novel immunotherapies against invasive fungal infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Highly purified Escherichia coli LPS (cat#, 437627) was purchased from Calbiochem, Laminarin from Laminaria digitata (cat#, L9634), β-1,3-D-glucanase from Aspergillus niger (cat#, 49101), and 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA; cat#, D6883) were all obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Purified particulate β-glucan (curdlan) was from Waiko (Tokyo, Japan). Yeast whole glucan particles (WGP) were from Biothera. For immunofluorescence imaging studies, WGP was labeled with fluorescein dichlorotriazine (DTAF; Molecular Porbes-Invitrogen). b-(1–3)-glucan-specific monoclonal antibody (cat#, 400-2) was from Biosupplies (Parkville, Australia). Blocking monoclonal antibody for Dectin-1 [GE2] (cat#, ab82888; 10 µg/ml) was from Abcam. TLR-2 (10 µg/ml), and TLR-4 (10 µg/ml) and appropriate isotype control antibodies were from eBioscience. In some experiments highly purified Bartonella LPS was used as a potent TLR-4 inhibitor. A specific syk kinase inhibitor (1µM) (cat#, 574711), piceatannol (40 µM) (cat#, 527948), and raf-1 inhibitor (40 µM) (cat#, 553008) were from Calbiochem. Hydrocortisone (Lyo-cortin) was from Vianex S.A.. Anti- LC3 antibody used for immunofluorescence was from Nanotools (0231-100/LC3-5F10). FITC conjugated Dectin-1 antibody (MCAA4661FT) was from AbD Serotec. Latex beads of 3µm diameter were purchased from Sigma. Coating of latex beads with IgG or BSA was performed by overnight rotating incubation at 4 °C with human IgG (1 mg/ml) or BSA (1 mg/ml) followed by 3 washes with PBS.

Isolation and stimulation of human primary cells from patients and controls

Healthy volunteers without any known infectious or inflammatory disorders donated blood as a control group for the assessment of LC3 II recruitment in fungal phagosomes. In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from three patients with CGD harboring homozygous mutations in the NCF1 gene (p47-phox) in which the complete absence of ROS production has been demonstrated, and 3 homozygous patients with the early stop-codon mutation Tyr238X in Dectin-1 (Dectin 1−/−). After informed consent, blood was collected by venipuncture from these patients and volunteers into 10-ml EDTA tubes. Six consecutive patients with various rheumatologic diseases receiving treatment with a standard dose of corticosteroids (Table 1) were recruited from the Rheumatology Department, University Hospital of Heraklion (Greece).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with rheumatologic diseases who received iv corticosteroids

| Patient Initials (Pt#) |

Sex | Age | Underlying Disease |

Disease Status |

Co-morbidities | Other Immunosuppressive agents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.T. (Pt#1) | F | 62 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Active disease | Multiple sclerosis | Methotrexate, rituximab (anti- CD20) |

| O.D (Pt#2) | F | 68 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Active disease, extra articular manifestations (rheumatoid lung) | Hepatitis B | Leflunomide, rituximab (anti- CD20), receipt of anti-TNFa monoclonal antibody in the past 12 months |

| S.A. (Pt#3) | F | 63 | Systemic lupus erythematoso us | In remission | Cirrhosis (autoimmune hepatitis) | Azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, rituximab (anti- CD20) |

| L.S. (Pt#4) | F | 46 | Polymyositis | In remission | Parkinson disease, pulmonary embolism | Methotrexate, low dose prednisone (5mg daily) in the past 6 months |

| K.M. (Pt#5) | F | 56 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Active disease, extra articular manifestations (pericarditis) | N/A | Methotrexate, rituximab (anti- CD20), receipt of anti-IL6 monoclonal antibody in the past 6 months |

| A.M. (Pt#6) | F | 61 | Rheumatoid arthritis | In remission | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Methotrexate, low dose prednisone (2.5 mg daily) in the past 6 months |

All patients received corticosteroids (methyl prednisone or hydrocortisone) at a standard dose of 250mg of hydrocortisone equivalent as premedication for prevention of infusional reactions associated with the use of rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody). Blood was drawn before (0h) and after (2h) iv treatment with corticosteroids.

Monocytes from healthy controls, and patients were isolated from PBMCs using magnetic bead separation with anti-CD14 coated beads (MACS miltenyi Germany) according to the protocol supplemented by the manufacturer. The monocytes were resuspended in RPMI culture medium supplemented with gentamicin 1%, L-glutamine 1%, and pyruvate 1%. The cells were counted in a Bürker counting chamber, and their number was adjusted to 1 × 106/ml. 2 × 105 monocytes per condition in a final volume of 200µL were allowed to adhere to glass coverslips (Ø12mm) for 1 hour after which they were exposed to A. fumigatus spores at a MOI of 3:1 at 37°C for 1 hour. After stimulation the coverslips were washed twice with PBS to remove medium and non-phagocytosed spores and cells were fixed on the coverslips for 15 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequently the coverslips were washed with PBS followed by a fixation in ice cold methanol for 10 minutes in −20 °C after which cover slips were stored in PBS at 4°C until immunofluorescence staining was performed.

Microorganisms and culture conditions

The Aspergillus fumigatus strains Af293, ATCC 46645 and the GFP-Aspergillus fumigatus strain (kind gift of KA Marr) were used in this study. All isolates were grown on YAG agar plates for 3 days at 37°C. Fungal spores in the presence of sterile 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS were harvested by gentle shaking, washed twice with PBS, filtered through a 40-µm-pore-size cell strainer (Falcon) to separate conidia from contaminating mycelium, counted by a hemacytometer, and suspended at a concentration of 108 spores/ml. Swollen spores of A. fumigatus were obtained following growth in liquid RPMI 1640 media for 4 h to 6 h at 37°C. Typically, > 90% of fungal spores were visibly swollen. The conidia were labeled with FITC as previously described9. Briefly, freshly harvested conidia (5 × 107/2 ml of 50 mM Na carbonate buffer [pH 10.2]) were incubated with FITC at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml at 37°C for 1 h and washed by centrifugation three times in PBS-0.1% Tween 20.

Enzymatic digestion of β-glucan in swollen spores of A. fumigatus was performed by using b-1–3-D-glucanase (Sigma). A. fumigatus spores were incubated overnight in a water bath with 100 U/ml of β-glucanase at a temperature of 55°C and pH 5, 0. Inactivation of enzyme was achieved by 10 min incubation at 100°C followed by three washes in PBS. Verification of β-glucan digestion was performed by immunostaining with a β-glucan monoclonal antibody. Inactivation of fungi was done by heat exposure (30 min, 65 C) or exposure to 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA; 4°C, overnight) following by treatment with glycine (100 mm/PBS) and three washes in PBS. PFA-inactivation of A. fumigatus spores had no effect on β-glucan surface exposure as evidenced by immunostaining.

Immunofluorescence staining

For immunofluorescence imaging, cells were seeded in coverslips pretreated with poly lysine, fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min in room temperature following by 10 min of fixation with ice cold methanol in −20 °C, washed twice with PBS, permeabilized by using 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich), blocked for 30 min in PBS plus 2% BSA, incubated for 1h with a mouse monoclonal antibody to LC3 (1:50, Nanotools), washed twice in PBS plus 2% BSA, stained by a secondary AlexaFluor555 goat anti-mouse Ab (1:500, Molecular Probes), followed by DNA staining with 10 µM TO-PRO-3 iodide (642/661; Invitrogen). After the washing steps, slides were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade media (Molecular Probes). Images were acquired using a laser-scanning spectral confocal microscope (TCS SP2; Leica), LCS Lite software (Leica), and a 40× Apochromat 1.25 NA oil objective using identical gain settings. A low fluorescence immersion oil (11513859; Leica) was used, and imaging was performed at room temperature. Unless otherwise stated, mean projections of image stacks were obtained using the LCS Lite software and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Phagosome acidification was assessed by use of the acidotropic dye LysoTracker Red DND-99 according to Invitrogen instructions (Invitrogen). Briefly, THP-1 cells were seeded on coverslips in 24 well flat bottom plates and differentiated to macrophages following 48h exposure to PMA (100 µg/ml) in RPMI-10% FCS media. Cells were preloaded with LysoTracker (diluted 1:20,000 [vol/vol] in RPMI complete medium) for 2 h and were subsequently infected at 4°C with FITC-labeled A. fumigatus conidia (MOI 5:1) in fresh medium without LysoTracker. After removal of uningested conidia by washing with warm RPMI media, medium with LysoTracker was readded to each well and conidia internalization was initiated at 37°C. Infection was stopped after 2 h, and the cells were washed with PBS, mounted on microscope slides, and examined immediately under the confocal microscope.

For β-glucan immunostaining of A. fumigatus live or PFA-inactivated spores (2 × 107/ condition) were pelleted in propylene tubes, washed twice with PBS, blocked for 30 min in PBS plus 2% BSA, incubated for 1 h with a mouse monoclonal antibody to linear-(1,3)-β-glucan (Biosupplies; 1 µg/ml) at room temperature, washed twice in PBS plus 2% BSA, stained by a secondary AlexaFluor 555 goat anti-mouse Ab (Molecular probes).and images were acquired by confocal microscopy.

Immunoelectron LC3 microscopy in monocytes

Immunoelectron microscopy was performed using mouse monoclonal LC3 antibody (Nanotools), applying the preembedding gold enhancement method as described previously25. Primary human monocytes cultured on poly lysine pretreated coverslips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Nacalai Tesque) for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with the same buffer three times for 5 min, the fixed cells were permeabilized using 0.25% saponin in PBS. The cells were washed with PBS, blocked by incubating for 30 min in PBS containing 0.1% saponin, 10% BSA, 10% normal goat serum, then exposed overnight to 0.01 mg/ml of anti-LC3 mouse monoclonal antibody or to 0.01 mg/ml of rat serum in the blocking solution. After washing with PBS containing 0.005% saponin, the cells were incubated with colloidal gold (1.4-nm diameter; Nanoprobes)-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG in the blocking solution for 2 h. The cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 min. After washing with 50 mM glycine in PBS, 1% BSA in PBS, and finally with milliQ water (Millipore), gold labeling was intensified with a gold enhancement kit (GoldEnhance EM; Nanoprobes) for 3 min at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After washing with distilled water, the cells were postfixed in 1% OsO4 containing 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide in PBS for 60 min at room temperature, and washed with distilled water. The cells were dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol solutions and embedded in epoxy resin. After the epoxy resin hardened, the plastic coverslip was removed from it. Ultrathin sections were cut horizontally to the cell layer and double stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Samples were analyzed with an electron microscope. Serial sections were collected on pioloform-coated copper grids and samples analyzed in a Philips (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) CM100 electron microscope.

Western Blot analysis

Primary human monocytes were stimulated with Aspergillus fumigatus conidia for the indicated time points at a MOI 10: 1. Where appropriate, cells were preincubated with DMSO or the indicated concentrations of inhibitors for 30 min prior to stimulation. Cells were washed once in phosphate-buffered saline prior to lysis in 1% NP-40 containing RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0,25% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1mM PMSF plus a mixture of protease inhibitors [Roche Molecular Biochemicals]). Cell lysis was performed on ice for 20 min and samples were centrifuged. After protein estimation of supernatants, addition of SDS sample buffer and boiling, samples were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Western blotting was performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer using the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-LC3 (NB100-2220, Novus), mouse anti-actin (MAB 1501, Millipore), mouse anti-tubulin (T5168, Sigma), rabbit anti-Syk (sc-1077), rabbit anti-phospho Syk (Tyr525/526, 2710 Cell Signaling), and goat anti-ATG5 (sc-8666, Santa Cruz). Secondary antibodies used in western blotting were purchased from Cell Signaling (anti-rabbit HRP, anti-goat HRP) as well as Millipore (anti-mouse HRP). The blots were developed using chemiluminescence (ECL; Thermo Scientific).

Measurement of ROS production in human monocytes

ROS measurements were performed by means of a dichlorofluorescein assay26. Stock solution of dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 100mM. Human monocytes (2 × 105/well) were plated on 96-well round bottom plates, incubated at 37°C for the indicated time (2h) with or without hydrocortisone and accordingly stimulated for 1h with A. fumigatus spores in the presence of DCFH-DA added to a final concentration of 10µM. After 30-min of exposure, the content of the wells were transferred to vials and the fluorescence of the cells from each well measured by flow cytometry. Cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Killing of A. fumigatus spores by THP-1 cells

THP-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were maintained in complete medium containing RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 4.5 g/l glucose, and 10% FCS (v/v) at 37°C (5% CO2), with passage every 3 days. THP-1 cells were plated onto 12-well plates and allowed to differentiate in the presence of 100 µg/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma). Cells that were adherent after 48 h were utilized in phagocytosis and killing experiments. To measure macrophage killing of conidia, PMA was removed by adding fresh media and THP-1 cells were allowed to ingest A. fumigatus conidia at a MOI of 1: 10 for 1 h at 37 °C. Medium containing nonadherent, nonphagocytosed conidia was removed, and wells were washed three times using warm PBS. Macrophages were then allowed to kill conidia for 2 and 6 h before intracellular conidia were harvested. Macrophages were removed by scraping, placed in propylene tubes, snap frozen with the use of liquid nitrogen and rapidly thawed at 37°C to lyse the THP-1 cells and harvest conidia. The process of cellular lysis was performed twice and confirmed by light microscopy. Lysates left overnight at 4°C in RPMI 1640. The percentage of killing (number of nongerminated spores per 100 counted conidia) in the culture well after 6 to 8 h of incubation at 37°C was assessed under a microscope. Control wells containing only A. fumigatus conidia showed that the percentage of germination of the conidia used was always > 90%.

Silencing of Atg5 expression by specific short interfering RNA (siRNA)

Short interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting was used to knockdown Atg5 expression in human THP-1 monocytes. Human monocyte nucleofector kit (Amaxa, Gaithenberg, MD, USA) and Nucleofector device (Amaxa) were used for delivering siRNA into monocytes by following the instructions provided by the company. In brief, 1.5 × 106 THP-1 cells were suspended in 100 µl of human monocyte nucleofector solution (Amaxa) and transfected with siRNA at a final concentration of 100nM using the V-001 program. Transfected cells were immediately diluted with pre-warmed growth media and cultured in 12-well plates for 24h. THP-1 cells were allowed to differentiate for an additional 48h in the presence of PMA (25 µg/ml) and then used for experiments. The following siRNA pool of oligonucleotide sequences were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA): ATG5 RNAi (sc-41445) and Control RNAi oligonucleotide sequences (C RNAi; sc-37003) Specific gene knockdowns were assessed by immunoblotting.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance of differences was determined by Student’s t test and Bonferroni’s t test (p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant). Analysis was done in GraphPad Prism software (version V).

RESULTS

The autophagy protein LC3 II is selectively recruited in A. fumigatus phagosomes upon fungal cell wall swelling

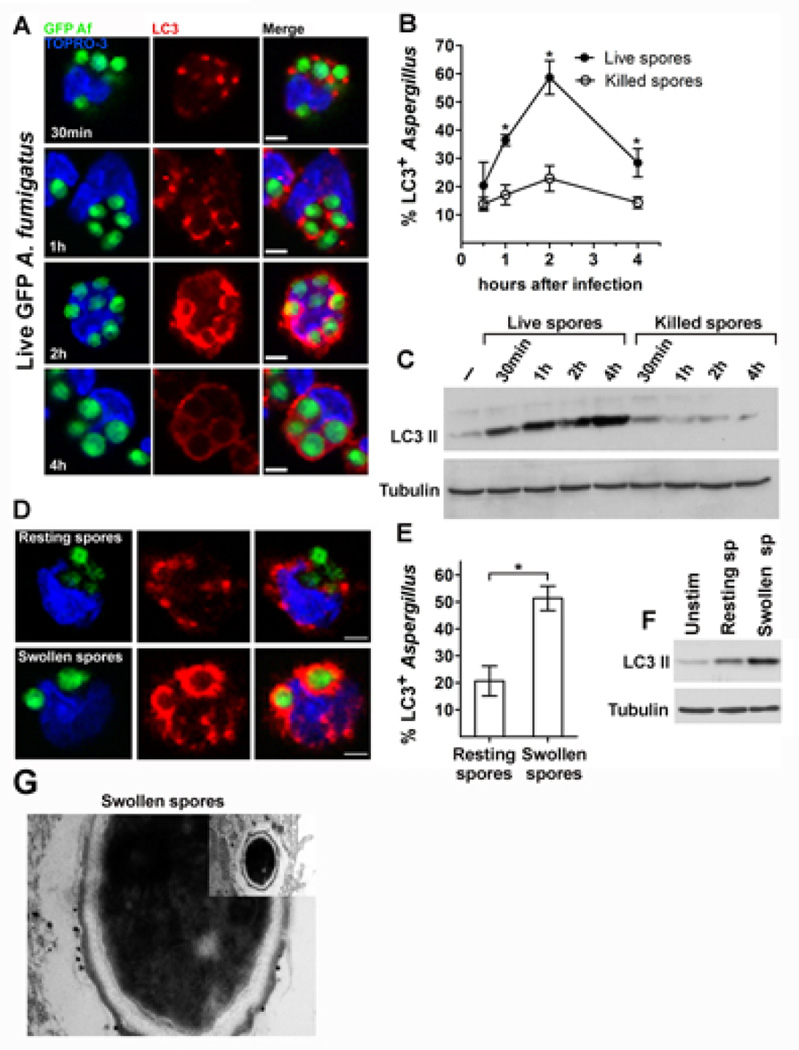

In order to evaluate whether autophagy proteins participate in immune responses against A. fumigatus, we monitored the kinetics of LC3 II recruitment to phagosomes of primary human monocytes infected with live spores of GFP- or FITC-labelled-A. fumigatus by immunostaining with the use of an LC3 specific antibody. In contrast to the previously reported rapid LC3+ phagosome formation, within minutes of the uptake of beads coated with TLR ligands24, we noticed a delayed LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes that was pronounced only after 2h of infection (Figure 1A). Next, we asked whether the formation of LC3+ phagosomes is elicited by fungal molecules that are either released or exposed during intracellular fungal cell wall swelling of A. fumigatus spores9. Thus, we infected human monocytes with paraformaldehyde (PFA)-killed resting (dormant) or PFA-killed swollen spores of A. fumigatus and assessed LC3 II recruitment. Surprisingly, we noticed minimal LC3 II recruitment in phagosomes even at late (4h) time points of infection of human monocytes with PFA-killed resting spores of A. fumigatus (Figure 1B). Similarly, while monocyte infection with live A. fumigatus spores triggered high levels of LC3 II protein expression, there was no evidence of significant LC3 II protein expression in monocytes infected with PFA-killed A. fumigatus resting spores (Figure 1C), by Western-blot analysis. In contrast to PFA-killed resting spores of A. fumigatus, PFA-killed swollen spores triggered robust LC3+ phagosome formation (Figure 1D, 1E) and pronounced LC3 II protein expression (Figure 1F) by Western-blot analysis. Collectively, these data reveal that LC3 II protein recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes is not dependent on release of soluble factors and occurs upon fungal cell wall swelling.

Figure 1. LC3 II is selectively recruited to phagosomes of primary human monocytes during cell wall swelling ofA. fumigatus.

A-B. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) isolated from healthy individuals were infected with live GFP A. fumigatus (GFP Af; A, B) or PFA-killed GFP A. fumigatus (B) at a MOI 5: 1 for the indicated times. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained for LC3 II with the use of an Alexa555 secondary antibody (red) and TOPRO-3 (blue, nuclear staining) and analyzed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. The percentages of LC3-associated A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus; n > 150 per group) at all time points were quantified by measuring the number of LC3+Aspergillus-containing phagosomes out of the total number of engulfed Aspergillus spores and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. Bar, 5 µm. C. Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) were infected with live GFP A. fumigatus or PFA-killed GFP A. fumigatus as in A-B for the indicated times. Cell lysates were prepared and levels of LC3 II protein were determined by immunoblotting. Levels of tubulin in the same lysates were determined by immunoblotting as loading controls. D-E. Primary human monocytes were stimulated for 1h with PFA-killed dormant or PFA-killed swollen spores of GFP A. fumigatus, fixed and stained as in A. The percentages of LC3+A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus; n > 150 per group) were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of 5 independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. Bar, 5 µm. F. Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) were left untreated (unstim) or stimulated with either PFA-killed dormant or PFA-killed swollen spores of A. fumigatus. Cell lysates were prepared and LC3 II and tubulin protein levels were determined by immunoblotting. G. Representative immunoelectron micrograph in which LC3 II was labeled in primary human monocytes stimulated for 1h with PFA-killed A. fumigatus swollen spores with 1.4-nm gold particles.

In agreement with previous studies that reported lack of classic double membrane autophagosome formation in LC3+ phagosomes containing TLR ligands23, we found that A. fumigatus swollen spores were contained within single membrane phagosomes, which was also suggested by the presence of gold conjugated antibody against LC3 only in the outer part of the phagosome membrane in immunoelectron microscopy studies (Figure 1G).

β-glucan surface exposure during fungal cell wall swelling triggers LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes

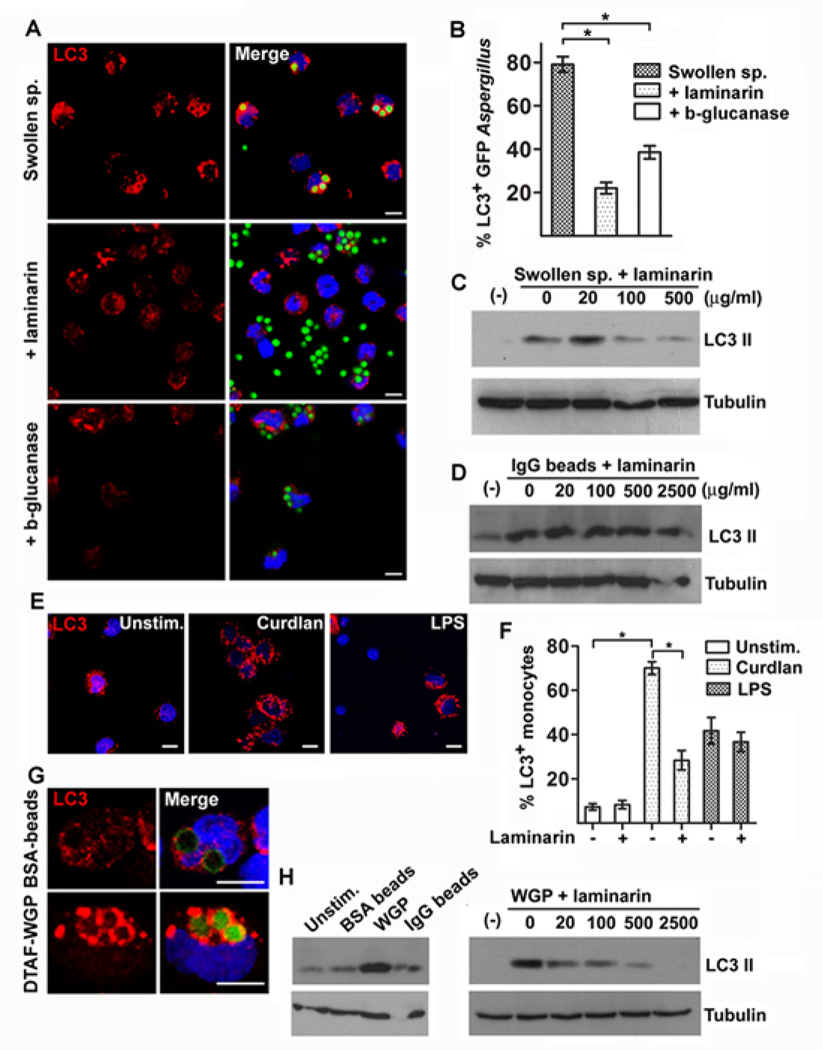

Recent studies demonstrated that resting A. fumigatus spores are immunologically inert because of concealing of immunostimulatory molecular patterns by a surface layer of hydrophobin27. Importantly, swelling of A. fumigatus spores leads to surface exposure of the immunostimulatory fungal polysaccharide β-1–3-D-glucan (β-glucan) and induction of robust inflammatory responses28. Therefore, we assessed whether stage-specific surface exposure of β-glucan in swollen spores of A. fumigatus accounts for selective LC3 II protein recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes. Accordingly, we performed enzymatic digestion of β-glucan in PFA-swollen spores of A. fumigatus by using a β-1–3-D-glucanase and assessed the effect on LC3 II protein recruitment in fungal phagosomes. Efficient digestion of β-glucan layer in A. fumigatus swollen spores was confirmed by immunofluorescence microscopy with the use of a β-glucan specific antibody. We found that enzymatic digestion of β-glucan resulted in significant reduction in LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation (Figure 2A, and 2B) following infection of human monocytes with swollen A. fumigatus spores. Furthermore, laminarin, a non-immunostimulatory soluble β-glucan that acts as competitive inhibitor of β-glucan receptors28, almost completely abolished LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation (Figure 2A and 2B) and LC3 II protein induction in human monocytes stimulated with swollen A. fumigatus spores (Figure 2C). Notably, laminarin treatment had no effect in LC3 II protein conversion in human monocytes stimulated with IgG coated latex beads (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. β-glucan surface exposure in swollen spores of A. fumigatus triggers LC3 II recruitment in fungal phagosomes.

A. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) isolated from healthy individuals were infected with GFP A fumigatus swollen spores with or without laminarin (500 µg/ml) or swollen spores following overnight enzymatic digestion of β-glucan (β-glucanase) at a MOI 5: 1 for 1h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained for LC3 II with the use of an Alexa555 secondary antibody (red) and TOPRO-3 (blue, nuclear staining) and analyzed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Bar, 5 µm. B The percentages of LC3+A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus n > 150 per group) were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of 3 independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. C Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) were stimulated with A. fumigatus swollen spores alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of laminarin, or (D) IgG coated 3mm latex beads alone or in the presence of increasing concentrations of laminarin for 1h. Cell lysates were prepared and levels of LC3 II protein were determined by immunoblotting. Levels of tubulin in the same lysates were determined by immunoblotting as loading controls. E-F. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) were left untreated or stimulated with purified β-gucan (curdlan, 100 µg/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml) with or without pretreatment with laminarin (500 µg/ml). The percentages of human monocytes containing autophagosomes as indicated by punctuate LC3 staining (LC3+ monocytes; n > 150 per group) were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of 2 independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t tes. Bar, 5 µm (G). Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) were stimulated with FITC-labeled BSA beads or DTFA-labeled WGP at a MOI 5: 1 for 1h. Cells were processed as in A and analyzed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Bar, 5 µm. (H). Primary human monocytes (1 × 106 cells/condition) were left untreated or stimulated with BSA coated-beads, IgG coated-beads or WGP with or without pretreatment with increasing concentration of laminarin at a MOI of 10:1 for 1h. Cell lysates were prepared and levels of LC3 II and tubulin were determined by immunoblotting.

The cell wall of A. fumigatus also contains galactomannan moieties29, and previous studies have implicated mannose- or mannan-specific receptors, including DC-SIGN and the long pentraxin PTX3, in the recognition of A. fumigatus30,31. To address the possible role of a mannose or mannan-specific receptor in LC3+ phagosome formation by swollen spores of A. fumigatus, we pretreated human monocytes with Saccharomyces cerevisiae–derived mannan31 prior to their addition to swollen spores and observed no effect on LC3 II recruitment by immunofluorescence imaging or LC3 II expression by western blot analysis, in contrast to the effect of laminarin (Supplementary Figure 1).

In order to confirm the ability of β-glucan to trigger LC3+ phagosome formation, we stimulated human monocytes with different forms of purified insoluble β-glucan, including curdlan and yeast-derived whole β-glucan particles (WGP) of approximately 3 µm size. Stimulation of human monocytes with curdlan particles elicited robust autophagosome formation that was blocked by pretreatment with laminarin (Figure 2E, and 2F); in contrast, laminarin had no measurable effect in autophagy induction by LPS in human monocytes (Figure 2F). In addition, stimulation of human monocytes with DTAF-labeled WGP resulted in a high degree of LC3+ phagosome formation, comparable to that induced by stimulation with IgG coated latex beads (Figure 2G). Similarly, we noticed high levels of LC3 II conversion following stimulation of human monocytes with WGP, a response completely inhibited by laminarin (Figure 2H). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that β-glucan surface exposure in A. fumigatus fungal cell wall activates the recruitment of the autophagy protein LC3 II in fungal phagosomes.

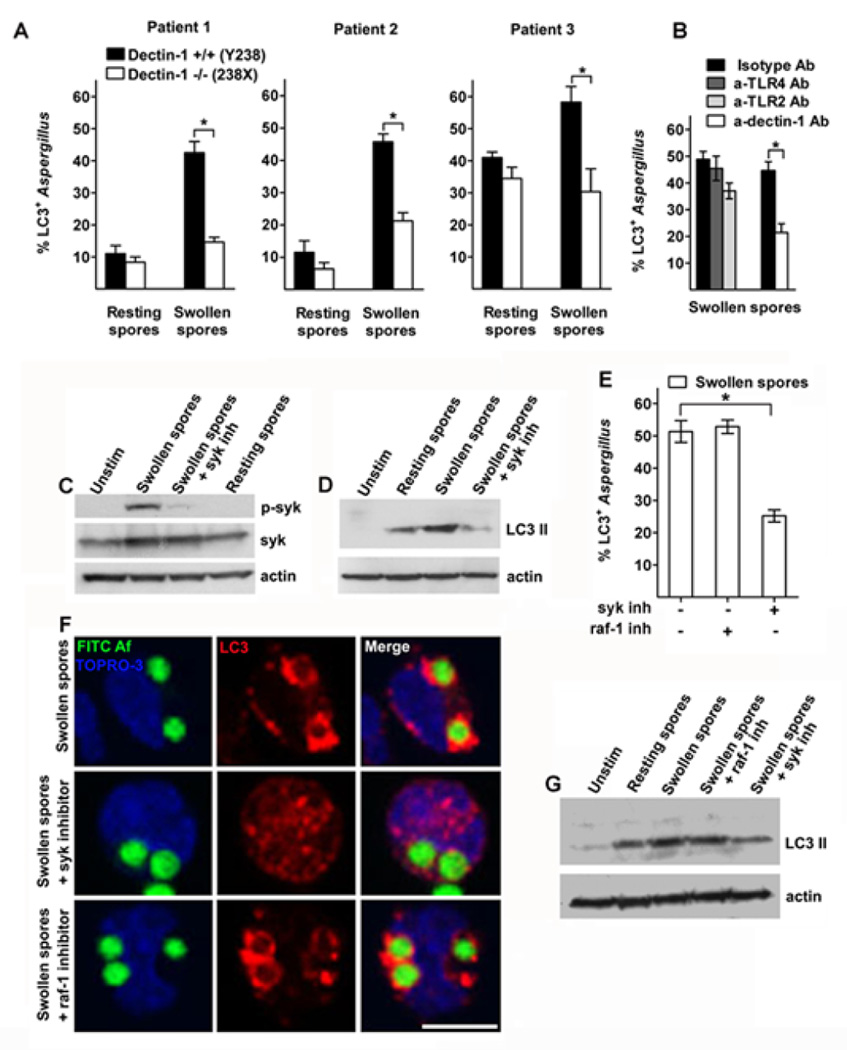

LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes depends on Dectin-1 signaling and is mediated by syk kinase

Sensing of β-glucan by human myeloid cells predominantly occurs via engagement of the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-116,17. Human patients with the homozygous early stop-codon mutation Tyr238X in Dectin-1 display lack of surface receptor expression, defective cytokine release and hypersusceptibility to mucocutaneous fungal infections20. We tested whether Dectin-1 receptor is involved in β-glucan induced LC3+ phagosome formation by infecting monocytes of three patients having homozygous Dectin-1 Tyr238X mutation (Dectin-1 −/−) with PFA-killed resting and swollen spores of A. fumigatus. We found that monocytes of Dectin-1 −/− patients had significant reduction in formation of LC3+ phagosomes following infection with swollen spores of A. fumigatus when compared to monocytes of Dectin-1 +/+ controls (Figure 3A and supplementary Figure 2). In addition, blocking of Dectin-1 receptor in monocytes from healthy individuals with the use of a specific antibody resulted in significant reduction in LC3+ phagosome formation following infection with swollen spores of A. fumigatus (Figure 3B). Because TLR-2 and TLR-4 receptors are the main TLRs involved in sensing of A. fumigatus2,14,15, we tested whether they also regulate autophagy protein recruitment in the phagosome. There was no evidence of significant reduction in LC3 II recruitment in phagosomes containing swollen spores of A. fumigatus following blockade of either TLR-2 receptor using TLR-2 specific antibody, or TLR-4 receptor using either TLR-4 specific antibody (Figure 3B) or Bartonella Quintana LPS, a specific TLR-4 inhibitor Because β-glucan has been reported to activate complement receptor 3 (CR3) in human phagocytes17, we blocked this receptor by using competitive inhibition with N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (NADG;32,33) and assessed the effect in LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation. We did not find significant reduction in LC3 II recruitment and LC3 II protein conversion in human monocytes pre-exposed to NADG and subsequently infected with swollen spores of A. fumigatus (Supplementary Figure 3). These studies suggest that LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes depends mainly on activation of Dectin-1 receptor.

Figure 3. Dectin-1/syk kinase signalling regulates LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes.

A. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) isolated from homozygous patients with the stop codon mutation 238X (Dectin-1 −/−) and healthy controls (Dectin-1 +/+) were infected with FITC-labeled resting or swollen spores of A. fumigatus at a MOI 5: 1 for 1h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for LC3 II as in Figure 1A. The percentages of LC3+A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus; n > 100 per group) were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.D. for each patient. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. B. Primary human monocytes from healthy individuals were stimulated with FITC-labeled swollen spores of A. fumigatus following 30 min pre-incubation with blocking antibodies for Dectin-1 (10 µg/ml), TLR-2 (10 µg/ml), or TLR-4 (10 µg/ml) or the indicated isotype control antibodies (10 µg/ml) at a MOI 5: 1 for 1h at 37 °C. Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy as in Fig 1A. C. Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) from healthy individuals were either left untreated, or stimulated with resting spores of A. fumigatus, or swollen spores of A. fumigatus with or without 30 min pretreatment with syk inhibitor (1µM) at a MOI 10:1 for 10 min at 37 °C. Cell lysates were prepared and levels of phospho-syk activity were determined by immunoblotting. Levels of tubulin and total syk in the same lysates were determined by immunoblotting as loading controls. D. Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) were stimulated as in C for 1h at 37 °C and levels of LC3 II and tubulin were determined in cellular lysates by immunoblotting. E-F. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) were stimulated with FITC-labeled swollen spores of A. fumigatus with or without 30 min pretreatment with syk inhibitor (1µM) or raf-1 inhibitor (40µM) at a MOI of 5:1 for 1h and processed for immunostaining as in A. The percentages of LC3+A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus; n > 150 per group) were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of four independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. Bar, 5 µm. G. Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) stimulated as in E and levels of LC3 II and tubulin were determined in cellular lysates by immunoblotting.

Coupling of syk kinase with Dectin-1 and other c-type lectin receptors activates multiple downstream pathways16,17,34. However, the role of syk kinase in phagosome maturation has not been earlier evaluated. In agreement with stage specific pattern of β-glucan exposure in cell wall surface of A. fumigatus, we found selective activation of syk kinase following monocyte infection with swollen and not with resting spores of A. fumigatus (Figure 3C). Importantly, treatment of human monocytes with two different syk kinase inhibitors almost completely abolished LC3 recruitment in phagosomes containing swollen A. fumigatus spores and blocked LC3 II protein conversion by Western-blot analysis (Figure 3D, E). Similarly, treatment with syk kinase inhibitor blocked LC3 recruitment in phagosomes containing purified β-glucan particles (WGP; Supplementary figure 3). Of interest, syk kinase inhibitors also blocked LC3 recruitment in phagosomes containing IgG coated latex beads (Supplementary figure 3), implying that syk kinase controls LC3+ phagosome formation upon activation of a broad range of pattern recognition receptors that contain ITAM motifs.

Raf-1 kinase has been implicated in Dectin-1 signaling via a syk-independent alternative non-canonical pathway of activation of NF-κB22. Thus, we tested whether signaling mediated by raf-1 kinase is involved in LC3 recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes. Blocking of raf-1 kinase by use of a specific raf-1 inhibitor did not cause significant reduction in LC3+ phagosome formation (Figure 3E, 3F) and LC3 II protein expression (Figure 3G) in human monocytes stimulated with swollen Aspergillus spores. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling regulates the formation of LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosomes.

Syk kinase-dependent ROS production regulates formation of LC3+ Aspergillus containing phagosomes

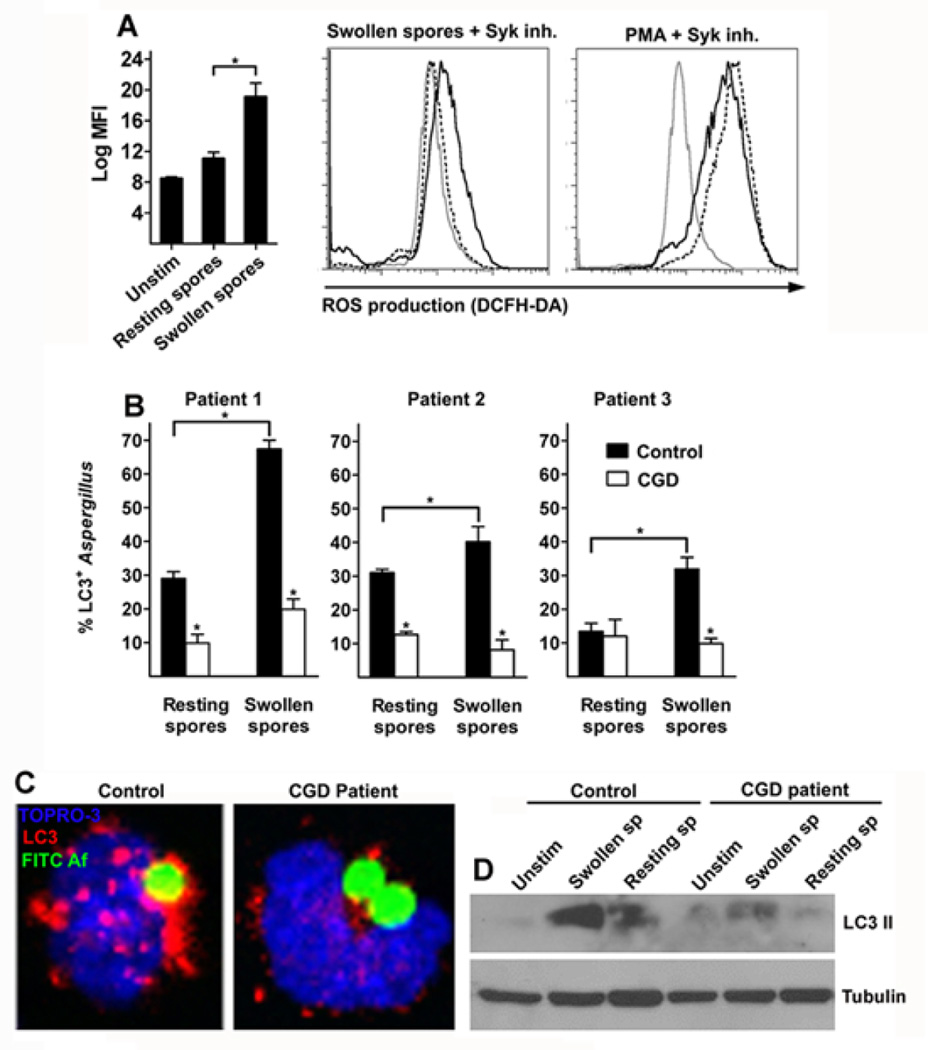

Recent studies implicate NOX-2 dependent ROS production in regulation of LC3 II recruitment in phagosomes of murine macrophages containing TLR and Fcγ receptor ligands24. Because syk kinase regulates ROS production in response to β-glucan16,17,34,35, we tested whether syk-mediated LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus containing phagosomes was dependent on production of ROS. We initially confirmed that similar to murine macrophages35, treatment with syk kinase inhibitor in primary human monocytes resulted in complete inhibition of ROS production in human monocytes stimulated with swollen A. fumigatus spores (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Syk kinase dependent ROS production regulates formation of LC3+ Aspergillus containing phagosomes.

A. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) were left unstimulated or infected with resting spores or swollen spores of A. fumigatus at a MOI of 5:1 with or without 30 min pretreatment with syk inhibitor (1 µM) or stimulated with PMA (100 ng/ml) with or without 30 min pretreatment with syk inhibitor (1 µM) for 1h at 37 °C. DCFH-DA was added during the last 30 min of stimulation and intracellular ROS production was determined by measurement of relative fluorescent intensity at the FL1 channel (log MFI). Differences in ROS production between experimental groups were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. from 4 independent experiments. *, P < 0.005, paired Student’s t test. Representative FL1 histograms from human monocytes left untreated (gray solid line), stimulated with either swollen spores of A. fumigatus alone or PMA alone (black solid line) or in the presence of syk inhibitor (black dashed lines) are shown. B-C. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) isolated from CGD patients and healthy controls were infected with FITC-labeled resting or swollen spores of A. fumigatus at a MOI 5: 1 for 1h at 37 °C. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for LC3 II as in Figure 1A. The percentages of LC3+A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus; n > 100 per group) were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.D. for each patient. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. Representative immunofluorescence image of LC3+ phagosomes containing FITC-labeled swollen spores of A. fumigatus in monocytes obtained from healthy control and CGD patient. D. Primary human monocytes (1 × 106 cells/condition) from a representative CGD patient and the corresponding healthy control were left untreated (unsitm) or stimulated with resting spores or swollen spores of A. fumigatus at a MOI 10:1 for 1h at 37 °C and levels of LC3 II and tubulin were determined in cellular lysates by immunoblotting.

Importantly, patients with GCD have mutations in various components of NADPH oxidase and unique susceptibility to invasive A. fumigatus infection via incompletely characterized mechanisms1,2,11. Thus, we tested whether abolished ROS production in monocytes of CGD patients results in defective LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes. When compared to monocytes of control healthy individuals, monocytes of three CGD patients displayed almost complete abolishment of LC3+ phagosome formation following infection with A. fumigatus (Figure 4B, and 4C). In addition, we noticed decreased LC3 II protein expression in lysates of monocytes from CGD patients infected with A. fumigatus in comparison to lysates of monocytes from healthy control patients infected with the fungus (Figure 4D). Therefore, NADPH derived ROS production regulates LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes and this pathway is defective in patients with CGD.

Silencing of Atg5 in human macrophages results in attenuated phagosome maturation and killing of A. fumigatus

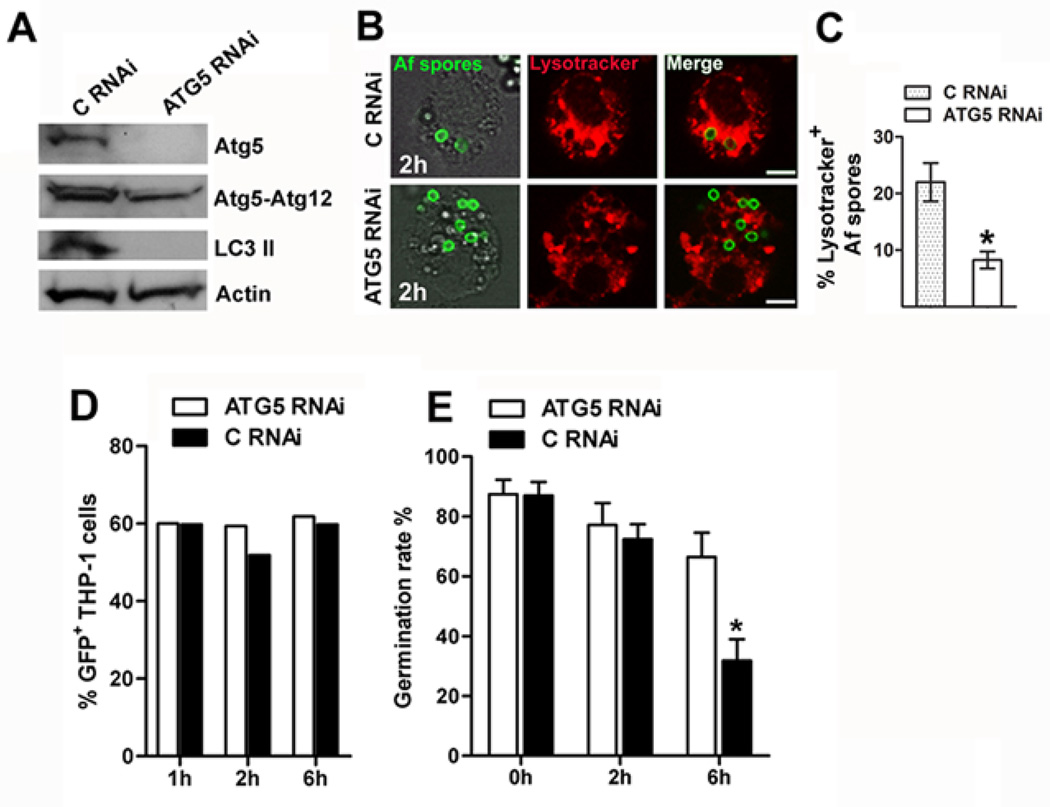

Recent studies demonstrated that silencing or knockdown of autophagy related genes Atg5 and Atg7 in murine macrophages resulted in impaired fusion of zymosan-containing phagosomes with lysosomes23, and defective killing of Saccharomyces cerevisiae23 and Candida albicans36. In order to evaluate the role of autophagy in human macrophage effector function against A. fumigatus, we performed silencing of Atg5 in THP-1 differentiated macrophages (Figure 5A), a human cell line previously shown to efficiently internalize and kill A. fumigatus37. Silencing of Atg5 in THP-1 macrophages resulted in significant reduction of the percentage of A. fumigatus spores within acidified lysosomes, as evidenced by lysotracker staining (Figure 5B, 5C).

Figure 5. Conditional inactivation of Atg5 in THP-1 human macrophages results in attenuated phagolysosomal fusion and killing of A. fumigatus.

A. THP-1 cells (1 × 106 cells/condition) were transfected with RNAi sequences targeting ATG5 vs. scramble control RNAi (C RNAi) by Amaxa electroporation. Cell lysates were prepared 48 h following transfection and levels of LC3 II, Atg5, and Atg5-Atg12 proteins were determined by immunoblotting. Levels of actin in the same lysates were determined by immunoblotting as loading controls. B-C. LysoTracker staining in THP-1 cells transfected with ATG5 RNAi or C RNAi and differentiated to macrophages with addition of PMA (25 ng/ml) following 2h of infection with FITC-labeled A. fumigatus spores. Data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of three independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test. Bar, 5 µm. D. Degree of association (uptake) of GFP A. fumigatus spores with THP-1 cells transfected with ATG5 RNAi or C RNAi and differentiated to macrophages in the presence of PMA (25 ng/ml) at different time points of infection (1h, 2h, 6h), assessed by FACS analysis. Results are representative of two independent experiments. E. THP-1 cells transfected by Amaxa nucelofection with ATG5 RNAi or C RNAi, were seeded in 12 well plates (5 × 105 cells/condition), differentiated with PMA (25 ng/ml) for 48 h and infected with A. fumigatus spores at a MOI of 1:10 at 37 °C. Medium containing nonadherent, nonphagocytosed conidia was removed at 1 h, and wells were washed three times using warm PBS. Macrophages were then allowed to kill conidia for 2 h and 6 h before intracellular conidia were harvested. The percentage of germinating spores in the culture well after 6 to 8 h of incubation at 37°C was assessed under a microscope. The percentage of germination rate (number of germinated spores per 100 counted conidia) of A. fumigatus spores following different time points of infection (1 h, 2 h, 6 h) was calculated and data are expressed as mean + S.E.M. of three independent experiments; * P = 0. 0003, paired Student’s t test.

We next assessed the effect of Atg5 silencing in killing of A. fumigatus by THP-1 macrophages. Previous studies demonstrated that elimination of A. fumigatus occurs following an initial 2h lag phase and reaches maximum levels at about 6h of infection9,10,37. In agreement with previous studies35, we found that THP-1 cells prevented germination of almost 60% of A. fumigatus spores at 6h of infection , whereas there was little evidence of inhibition of A. fumigatus growth at earlier (2h) time points of infection (Figure 5E). Silencing of Atg5 in THP-1 human macrophages had no significant effect on the uptake of fungal spores (Figure 5D), but resulted in attenuated killing of A. fumigatus (Figure 5E). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that autophagy proteins regulate phagosome maturation and intracellular killing of A. fumigatus.

Corticosteroids block LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes via inhibiting syk kinase-dependent ROS production

Prolonged treatment with corticosteroids is a major risk factor for development of invasive aspergillosis1–3. Seminal studies in the 1970s demonstrated that corticosteroids blocked the fusion of lysosomes with Aspergillus-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages and impaired killing of A. fumigatus12,13. However, the molecular mechanisms of the immunosuppressive action of corticosteroids that account for defective phagocyte effector function and development of invasive aspergillosis are currently unknown.

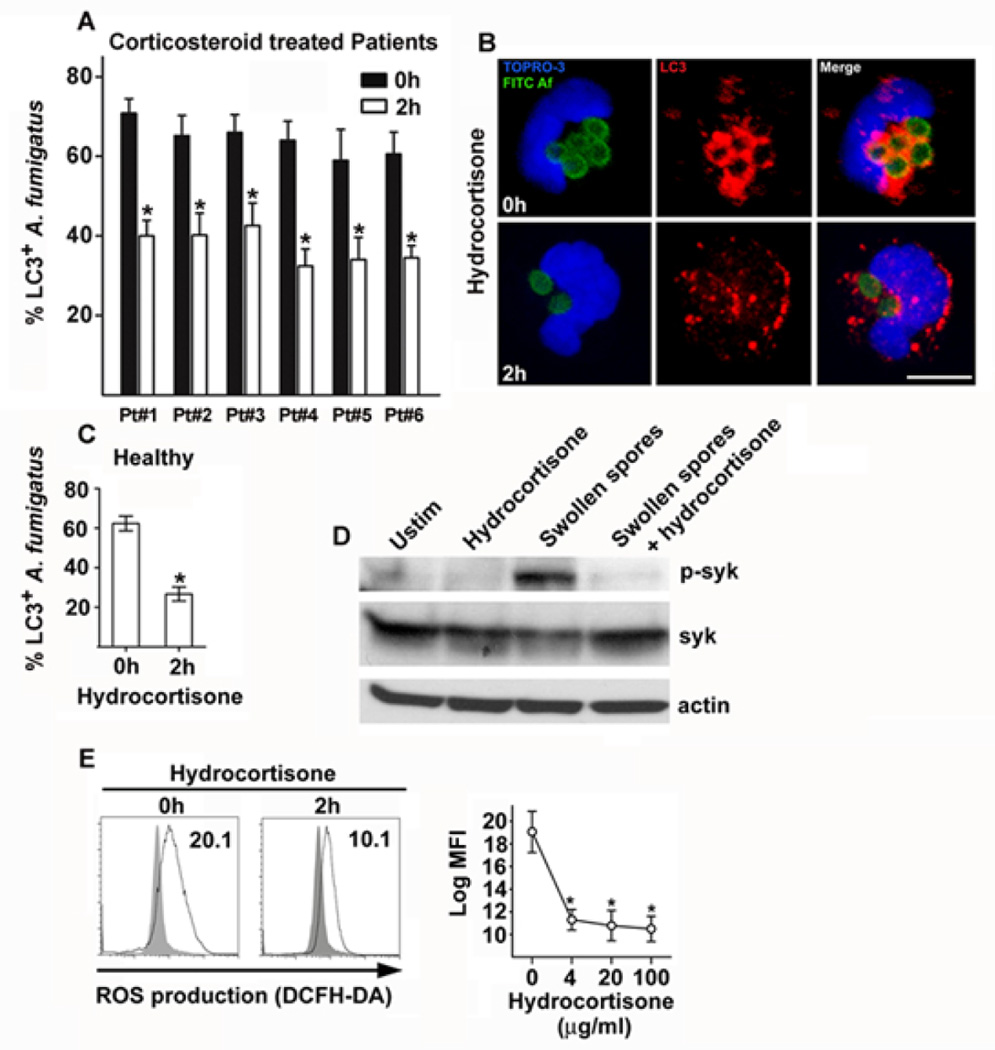

Since we found that components of autophagy pathway regulate phagosome maturation and A. fumigatus killing upon activation of Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling, we evaluated whether corticosteroids target this antifungal immune pathway. Therefore, we collected monocytes from consecutive patients with rheumatologic diseases who received intermittent infusion of a standard dose of corticosteroids (250 mg hydrocortisone equivalent), and infected them with swollen spores of A. fumigatus to assess the effect on LC3+ phagosome formation before and 2h after intravenous administration of corticosteroids. Notably, we found a significant reduction in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes following corticosteroid treatment in monocytes of all patients tested (Figure 6A and 6C). In addition, monocytes from healthy individuals pre exposed ex-vivo for 2h to hydrocortisone displayed significant reduction in LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation when compared to control untreated monocytes (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Corticosteroids block LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes via inhibiting phosphorylation of syk kinase and downstream ROS production.

A. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) from six consecutive patients with rheumatologic diseases were collected before and 2h after intravenous administration of corticosteroids (250 mg hydrocortisone) and stimulated with swollen spores of A. fumigatus at a MOI 5:1 at 37 °C. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, stained for LC3 II with the use of an Alexa555 secondary antibody (red) and TOPRO-3 (blue, nuclear staining) and analyzed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. The percentages of LC3+A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes (LC3+Aspergillus; n > 150 per group), before (0h) and after (2h) corticosteroid treatment, were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.D. for each patient. *, P < 0.05, paired Student’s t test. B. Representative immunofluorescence image of LC3+ phagosomes containing FITC-labeled swollen spores of A. fumigatus in monocytes obtained before (0h) and after (2h) administration of corticosteroids. Bar, 5 µm. C. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) from healthy individuals (n = 4) were stimulated before (0h) and after (2h) ex vivo exposure to hydrocortisone (20 µg/ml), fixed and processed as in A; data are presented as mean + S.E.M. of four independent experiments. P < 0.05, paired Student’s t test. D. Primary human monocytes (2 × 106 cells/condition) from healthy individuals were either left untreated with or without 1h exposure to hydrocortisone (20 µg/ml), or stimulated with swollen spores of A. fumigatus with or without 1h pre-exposure to hydrocortisone ((20 µg/ml) at a MOI 10:1 for 10 min at 37 °C. Cell lysates were prepared and levels of phospho-syk activity were determined by immunoblotting. Levels of tubulin and total syk in the same lysates were determined by immunoblotting as loading controls. E. Primary human monocytes (2 × 105 cells/condition) were left unstimulated or infected with swollen spores of A. fumigatus at a MOI of 5:1 for 1 h with or without pre-exposure (2 h) to increasing concentrations of hydrocortisone at 37 °C. DCFH-DA was added during the last 30 min of stimulation and intracellular ROS production was determined by measurement of relative fluorescent intensity at the FL1 channel (log MFI). Representative FL1 histograms from human monocytes left untreated (gray area), or stimulated with swollen spores of A. fumigatus (black solid line) with or without pre-exposure to hydrocortisone (20 µg/ml) are shown. Differences in ROS production between experimental groups were quantified and data are presented as mean + S.E.M. from 4 independent experiments. *, P < 0.0001, paired Student’s t test.

In order to gain insight in the molecular mechanism(s) of corticosteroid-mediated inhibition of LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes we assessed whether Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling regulating this pathway is also targeted by corticosteroids. Of interest, we found no difference in the uptake of A. fumigatus spores and the level of expression of Dectin-1 receptor following administration of corticosteroids in human monocytes, suggesting that corticosteroids may affect downstream signaling events following receptor activation (Supplementary figure 4). Previous studies reported that corticosteroids block T cell receptor (TCR) signaling by affecting early phosphorylating events induced after TCR ligation38,39. In particular, corticosteroids inhibited phosphorylation of ITAM motifs of TCR mediated by tyrosine kinases within 1h of administration both in vitro and in vivo, an effect mediated by direct interaction of glucocorticosteroid receptor with the TCR signalosome38,39. Importantly, there are no studies on the direct nongenomic action of corticosteroids in innate immune receptor signaling in phagocytic cells.

Because activation of C-type lectin receptors in myeloid cells via phosphorylation of ITAM motifs resembles activation of TCR signaling, we reasoned that corticosteroids might as well inhibit phosphorylation of syk tyrosine kinase in human monocytes. Therefore, human monocytes exposed at different time points to hydrocortisone at a dose that blocked LC3+ phagosome formation were stimulated for 10 min with swollen Aspergillus spores, and subsequently lysed and assessed for phosphorylation of syk kinase by Western-blot analysis. Importantly, we found that hydrocortisone administration caused a rapid block in phosphorylation of syk kinase, without affecting cytoplasmic levels of syk within minutes of administration, an effect that was more pronounced following 1h of pre-exposure (Figure 6D).

Corticosteroids have been previously shown to inhibit ROS production in murine macrophages following infection with A. fumigatus10. Because we found that in human monocytes ROS production in response to A. fumigatus infection is dependent on phosphorylation of syk kinase, we hypothesized that a blockade of syk kinase activation following hydrocortisone receipt would result in defective ROS production and subsequent defective LC3 II phagosome recruitment. Indeed, human monocytes treated with corticosteroids at doses that blocked LC3 II recruitment displayed a significant reduction in ROS production following infection with A. fumigatus (Figure 6E). These studies demonstrate that corticosteroids target autophagy protein recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes via inhibiting syk dependent ROS production, and provide a mechanistic explanation for their direct immunosuppressive properties in phagosome maturation and killing of Aspergillus spp.

DISCUSSION

In the present work we shed light in the signaling pathway regulating A. fumigatus phagosome maturation and uncover an important mechanism for development of invasive fungal disease. In particular, we found that activation of Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling upon exposure of β-glucan in A. fumigatus spores triggers the recruitment of autophagy protein LC3 II in fungal phagosomes. LC3 II recruitment requires syk kinase-dependent ROS production and is abolished in monocytes of patients with CGD, who display unique susceptibility for invasive aspergillosis. Furthermore, by silencing Atg5 in human phagocytes, we demonstrate that autophagy protein assembly is important for maturation of A. fumigatus phagosomes and fungal clearance. Very important from a clinical point of view, we also discovered that corticosteroids target the pathway of LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation by causing an early block in phosphorylation of syk kinase and downstream production of ROS.

Autophagy is a lysosomal degradation pathway that among other immune related actions mediates clearance of intracellular pathogens via their engulfment upon escape to the cytosol40. Little is known on the role of autophagy pathway in immunity against extracellular pathogens, including fungi. Recent studies implicating autophagy proteins in regulation of maturation of phagosomes containing TLR ligands prompted us to study the physiologic relevance of this pathway in immunity against A. fumigatus23,24. Our initial experiments identified that fungal cell wall swelling is the trigger for LC3 II recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes. Of interest, these studies provide a mechanistic explanation of previous observations by electron microscopy on the intracellular lifecycle of A. fumigatus, suggesting that fungal cell wall swelling is a prerequisite for efficient phagosome maturation and killing of A. fumigatus by murine macrophages9.

Because immunostimulatory β-glucans are selectively exposed at the surface of the fungal cell wall surface upon swelling of A. fumigatus spores28, we tested whether this could be the trigger for LC3 recruitment in fungal phagosomes. By using different assays, including β-glucan enzymatic digestion and competitive inhibition with the use of the soluble β-glucan laminarin, we found that LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation was dependent on sensing β-glucans. As a further proof-of-principle, purified β-glucan particles triggered robust LC3+ phagosome formation. Previous studies in the murine RAW macrophage cell line using zymosan, a crude fungal cell wall extract rich in β-glucans, reported robust LC3+ phagosome formation around zymosan particles mediated by TLR2 engagement23,24. However, because RAW macrophages express low levels of the β-glucan sensing receptor Dectin-141, and because zymosan is a mixture of β-glucan and TLR ligands, it was difficult to dissect the contribution of β-glucan sensing in LC3 recruitment. Overall, our study identified β-glucan as the key molecule activating recruitment of autophagy proteins in fungal phagosomes.

In a following set of experiments, we tested whether LC3+ Aspergillus phagosome formation was defective in monocytes of patients with the homozygous early stop-codon mutation Tyr238X in Dectin-1 (Dectin-1 −/−). Indeed, we found a significant reduction in recruitment of LC3 protein in monocytes of Dectin-1 −/− patients when compared to control Dectin-1 +/+ monocytes infected with A. fumigatus. Similarly, blocking Dectin-1 receptor in monocytes of healthy individuals with the use of a specific antibody resulted in significant reduction in LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosomes, whereas blocking TLR-2 and TLR-4 did not affect LC3 recruitment. In addition, blocking of mannose, mannan receptors and the lectin binding site of CR3 had no significant effect in LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation in human monocytes. Our findings corroborate a recent study reporting that in murine dendritic cells and macrophages Dectin-1 activation was required for LC3 II recruitment in Candida albicans phagosomes43. Thus, our study links activation of Dectin-1 receptor with autophagy protein recruitment in the phagosome of human phagocytes.

In addition, we assessed the role of syk kinase in LC3 recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes. Pharmacologic inhibition of syk kinase almost completely abolished LC3 protein recruitment in Aspergillus phagosomes. Notably, inhibition of raf-1 kinase that also activates an alternative signaling pathway downstream of Dectin-1 had no impact on LC3+ phagosome formation. Because syk kinase is downstream of many different signaling receptors34, our finding could have broad spectrum implications on regulation of autophagy responses following sensing of endogenous or pathogen-related ligands. For example, LC3 recruitment following stimulation of primary human monocytes with IgG coated beads, a response dependent on activation of Fcγ receptors, was also dependent on syk kinase. Although there are no previous studies on the role of syk kinase in phagosome maturation, conditional inactivation of syk in murine neutrophils resulted in impaired clearance of bacterial pathogens without a significant effect on phagocytosis42.

NADPH oxidase-derived ROS production was recently shown to regulate recruitment of autophagy proteins in phagosomes of murine macrophages containing TLR or Fc-gamma receptor ligands24. In agreement with previous studies in murine and human phagocytes demonstrating that ROS production in response to zymosan is dependent on activation of syk kinase35, we found that ROS production was selectively induced in response to swollen spores of A. fumigatus in a syk-dependent fashion. Studies in monocytes of CGD patients also revealed a block in LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation, confirming that NADPH derived ROS also regulate recruitment of autophagy proteins in fungal phagosomes. Because patients with CGD have increased susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis1,2,11, and macrophages of mice with mutations in NADPH oxidase display defective phagolysosomal fusion and killing following the uptake of A. fumigatus spores10, our studies suggest that defective autophagy protein recruitment could play an important role for development of invasive fungal infections in CGD.

Previous studies in murine macrophages demonstrated an important role of Atg7 and Atg5 proteins in phagosome maturation and clearance of yeast, including S. cerevisiae and C. albicans23,37. We also found that silencing of Atg5 in human THP-1 macrophages did not affect the uptake of fungal spores, but resulted in impaired maturation of A. fumigatus phagosomes and attenuated killing of the fungus. In humans, there are no previous studies to suggest a link between defective autophagy protein function and invasive fungal disease. Because full disruption of Atg5 is lethal in mice44 and human patients with homozygous loss-of-function mutations in Atg5 have not been described, it has been difficult to assess the direct in vivo role of autophagy in Aspergillus immunity. An important future direction of research is represented by genetic association studies of polymorphisms in autophagy genes with susceptibility to fungal infection, studies that could validate the present in-vitro data in a clinical setting.

Finally, we assessed whether corticosteroids, the major risk factor for development of invasive aspergillosis, target autophagy protein recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes. Because the main immunosuppressive effect of corticosteroids in phagocyte effector function is mediated via inhibition of fusion of phagosomes with the lysosomes2,3,12,13, a process regulated by autophagy proteins, we reasoned that corticosteroids may possess a direct inhibitory action on recruitment of autophagy proteins in fungal phagosomes. Surprisingly, we found that administration of a relatively low dose of corticosteroids blocked LC3 recruitment in A. fumigatus phagosomes within 2h of exposure. This effect was consistent in all patients tested and was highly reproducible following ex vivo administration of hydrocortisone in monocytes of healthy individuals.

Because of the rapid inhibition of LC3+ A. fumigatus phagosome formation by hydrocortisone, we reasoned that this effect is mediated by nongenomic action of corticosteroids on Dectin-1/syk kinase signaling. Notably, corticosteroids had no effect on A. fumigatus uptake and expression of Dectin-1 receptor. Since corticosteroids have been shown to block tyrosine kinase phosphorylation within minutes of exposure in T cells39,40 and another study on B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia reported inhibition of p-syk kinase by methylprednisolone via activation of phosphatase PTP1B45, we focused on their effects in phosphorylation of syk kinase in monocytes. Notably, we found that hydrocortisone almost completely inhibited phosphorylation of syk kinase within 10 min of exposure. Because syk kinase regulates ROS production in response to A. fumigatus infection, and corticosteroids have been shown to block ROS in macrophages during fungal infection10, we tested whether hydrocortisone blocked ROS production in monocytes infected with A. fumigatus. Indeed, hydrocortisone caused a significant reduction in ROS production following infection with A. fumigatus. Of interest, recent studies on T cells demonstrate that glucocorticoids induce macroautophagy prior to the induction of apoptosis, because of their ability to inhibit Src kinases and downstream IP3-mediated calcium signaling46. Thus, our studies reveal a selective property of corticosteroids to inhibit LC3 recruitment in fungal phagosomes, which is regarded as a specialized form of autophagy.

Collectively, we discovered a new antifungal immunity pathway that links dectin-1/syk kinase signaling with intracellular elimination of A. fumigatus. This pathway has major physiologic relevance for the control of fungal infection by human phagocytes as evidenced by impaired autophagy protein recruitment in A. fumigatus-containing phagosomes in two distinct groups of patients with increased susceptibility for invasive aspergillosis. Therefore, our studies unravel a new pathway with important physiologic relevance in fungal disease and provide a mechanistic explanation for the defective phagocyte function of individuals with susceptibility for invasive aspergillosis. Moreover, future studies are warranted to explore the therapeutic potential of autophagy induction in these patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yiannis Dalezios for assistance in electron microscopy studies. The authors have no conflicting financial interests in this work. This work was supported by a Marie Curie International Reintegration Grant (IRG-260210) to G.C., and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Core Grant (CA16672) from the University of Texas to D.P.K. M.G.N. was supported by an ERC Consolidator Grant (nr. 310372). F.vd V. was supported by a Veni grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

Contributions: E.K., M.S.G., T.A., and G.C. analyzed data and performed experiments. G.C. conceived and supervised the study, designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. G.S., P.S., D.B. D.P.K., M.G.N., and F.L.V. analyzed the data. M.G.N. and F.L.V. contributed reagents.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dagenais TR, Keller NP. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(3):447–465. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romani L. Immunity to fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(4):275–288. doi: 10.1038/nri2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lionakis M, Kontoyiannis DP. Glucocorticoids and invasive fungal infections. Lancet. 2003;362(9398):1828–1838. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14904-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornillet A, Camus C, Nimubona S, et al. Comparison of epidemiological, clinical, and biological features of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic and nonneutropenic patients: a 6 year survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(5):577–584. doi: 10.1086/505870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ader F, Nseir S, Le Berre R, et al. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an emerging fungal pathogen. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(6):427–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Van Wijngaerden E. Invasive aspergillosis in the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(2):205–216. doi: 10.1086/518852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaffner A, Douglas H, Braude A. Selective protection against conidia by mononuclear and against mycelia by polymorphonuclear phagocytes in resistance to Aspergillus: observations on these 2 lines of defense in vivo and in vitro with human and mouse phagocytes. J Clin Invest. 1982;69(3):617–631. doi: 10.1172/JCI110489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldorf AR, Levitz SM, Diamond RD. In vivo bronchoalveolar macrophage defense against Rhizopus oryzae and Aspergillus fumigatus . J Infect Dis. 1984;150(5):752–760. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ibrahim-Granet O, Philippe B, Boleti H, et al. Phagocytosis and intracellular fate of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia in alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun. 2003;71(2):891–903. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.891-903.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philippe B, Ibrahim-Granet O, Prévost MC, et al. Killing of Aspergillus fumigatus by alveolar macrophages is mediated by reactive oxidant intermediates. Infect Immun. 2003;71(6):3034–3042. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3034-3042.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morgenstern DE, Gifford MA, Li LL, Doerschuk CM, Dinauer MC. Absence of respiratory burst in X-linked chronic granulomatous disease mice leads to abnormalities in both host defense and inflammatory response to Aspergillus fumigatus. J Exp Med. 1997;185(2):207–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merkow L, Pardo M, Epstein SM, Verney E, Sidransky H. Lysosomal stability during phagocytosis of Aspergillus flavus spores by alveolar macrophages of cortisone-treated mice. Science. 1968;160(3823):79–81. doi: 10.1126/science.160.3823.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaffner A. Therapeutic concentrations of glucocorticoids suppress the antimicrobial activity of human macrophages without impairing their responsiveness to gamma interferon. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(5):1755–1764. doi: 10.1172/JCI112166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mambula SS, Sau K, Henneke P, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling in response to Aspergillus fumigatus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(42):39320–39326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellocchio S, Montagnoli C, Bozza S, et al. The contribution of Toll-like/IL-1 receptor superfamily to innate and adaptive immunity to fungal pathogens in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172(5):3059–3069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drummond RA, Brown GD. The role of Dectin-1 in the host defense against fungal infections. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14(4):392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodridge HS, Wolf AJ, Underhill DM. Beta-glucan recognition by the innate immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;230(1):38–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gringhuis SI, Wevers BA, Kaptein TM, et al. Selective C-Rel activation via Malt1 controls antifungal T(H)-17 immunity by dectin-1 and dectin-2. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(1):e1001259. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werner JL, Metz AE, Horn D, et al. Requisite role of dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor in pulmonary defense against Aspergillus fumigatus. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):4938–4946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferwerda B, Ferwerda G, Plantinga TS, et al. Human dectin-1 deficiency and mucocutaneous fungal infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(18):1760–1767. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunha C, Di Ianni M, Bozza S, et al. Dectin-1 Y238X polymorphism associates with susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis in hematopoietic transplantation through impairment of both recipient- and donor-dependent mechanisms of antifungal immunity. Blood. 2010;116(24):5394–5402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gringhuis SI, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, et al. Dectin-1 directs T helper cell differentiation by controlling noncanonical NF-kappaB activation through Raf-1 and Syk. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(2):203–213. doi: 10.1038/ni.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanjuan MA, Dillon CP, Tait SW, et al. Toll-like receptor signaling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/nature06421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang J, Canadien V, Lam GY, et al. Activation of antibacterial autophagy by NADPH oxidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(15):6226–6231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811045106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo H, Nakatsu F, Furuno A, Kato H, Yamamoto A, Ohno H. Visualization of the post-Golgi trafficking of multiphoton photoactivated transferrin receptors. Cell Struct Funct. 2006;31(2):63–75. doi: 10.1247/csf.31.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using a microplate reader. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(5–6):612–616. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aimanianda V, Bayry J, Bozza S, et al. Surface hydrophobin prevents immune recognition of airborne fungal spores. Nature. 2009;460(7259):1117–1121. doi: 10.1038/nature08264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohl TM, Van Epps HL, Rivera A, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus triggers inflammatory responses by stage-specific beta-glucan display. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1(3):e30. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontaine T, Simenel C, Dubreucq G, et al. Molecular organization of the alkali-insoluble fraction of Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):27594–27607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909975199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persat F, Noirrey N, Diana J, et al. Binding of live conidia of Aspergillus fumigatus activates in vitro-generated human Langerhans cells via a lectin of galactomannan specificity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133(3):370–377. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serrano-Gomez D, Dominguez-Soto A, Ancochea J, et al. Dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin mediates binding and internalization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by dendritic cells and macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;173(9):5635–5643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thornton BP, Vetvicka V, Pitman M, Goldman RC, Ross GD. Analysis of the sugar specificity and molecular location of the beta-glucan-binding lectin site of complement receptor type 3 (CD11b/CD18) J Immunol. 1996;156(3):1235–1246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross GD, Cain JA, Lachmann PJ. Membrane complement receptor type three (CR3) has lectin-like properties analogous to bovine conglutinin as functions as a receptor for zymosan and rabbit erythrocytes as well as a receptor for iC3b. J Immunol. 1985;134(5):3307–3315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mocsai A, Ruland J, Tybulewicz VL. The SYK tyrosine kinase: a crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):387–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Underhill DM, Rossnagle E, Lowell CA, Simmons RM. Dectin-1 activates Syk tyrosine kinase in a dynamic subset of macrophages for reactive oxygen production. Blood. 2005;106(7):2543–2550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicola AM, Albuquerque P, Martinez LR, et al. Macrophage autophagy in immunity to Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2012;80(9):3065–3076. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00358-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marr KA, Koudadoust M, Black M, Balajee SA. Early events in macrophage killing of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia: new flow cytometry viability assay. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8(6):1240–1247. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.6.1240-1247.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Löwenberg M, Tuynman J, Bilderbeek J, et al. Rapid immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids mediated through Lck and Fyn. Blood. 2005;106(5):1703–1710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Löwenberg M, Verhaar AP, Bilderbeek J, Marle Jv, Buttgereit F. Glucocorticoids cause rapid dissociation of a T-cell-receptor-associated protein complex containing LCK and FYN. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(10):1023–1029. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuballa P, Notle WM, Castoreno AB, Xavier RJ. Autophagy and the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:611–646. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown GD, Herre J, Williams DL, Willlment JA, Marshall AS, Gordon S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J Exp Med. 2003;197(9):1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma J, Becker C, Lowell CA, Underhill DM. Dectin-1-triggered Recruitment of Light Chain 3 Protein to Phagosomes Facilitates Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Presentation of Fungal-derived Antigens. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(41):34149–34156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.382812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA. Neutrophil-specific deletion of Syk kinase results in reduced host defense to bacterial infection. Blood. 2009;114(23):4871–4882. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432(7020):1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boelens J, Lust S, Van Bockstaele F, et al. Steroid effects on ZAP-70 and SYK in relation to apoptosis in poor prognosis chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2009;33(10):1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harr MW, McColl KS, Zhong F, Molitoris JK, Distelhorst CW. Glucocorticosteroids downregulate Fyn and inhibit IP(3)-mediated calcium signaling to promote autophagy in T lymphocytes. Autophagy. 2010;6(7):912–921. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.7.13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]