Summary

DNA polymerase ζ (Polζ) is specialized for the extension step of translesion DNA synthesis (TLS). Despite its central role in maintaining genome integrity, little is known about its overall architecture. Initially identified as a homodimer of the catalytic subunit Rev3 and the accessory subunit Rev7, yeast Polζ has recently been shown to form a stable four-subunit enzyme (Polζ-d) upon incorporation of Pol31 and Pol32, the accessory subunits of yeast Polδ. To understand the 3-D architecture and assembly of Polζ and Polζ-d we employed electron microscopy. We show here how the catalytic and accessory subunits of Polζ and Polζ-d are organized relative to each other. In particular, we show that Polζ-d has a bilobal architecture resembling the replicative polymerases, and that Pol32 lies in proximity to Rev7. Collectively, our study provides the first views of Polζ and Polζ-d, and a structural framework for understanding their roles in DNA damage bypass.

Introduction

Cellular DNA is under constant attack by external and internal agents that cause lesions and block the progression of the DNA replication machinery. Both prokaryotes and eukaryotes possess specialized translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA polymerases (Pols) that can replicate through these lesions (Prakash et al., 2005). Most of the TLS polymerases belong to the Y-family, which includes the single subunit Polη, Polι, Polκand Rev1 in humans (Prakash et al., 2005). Polζ is a multi-subunit TLS polymerase that belongs to the B-family (Prakash et al., 2005; Sharma et al., 2013). It is specialized for the extension step of lesion bypass, whereby it is recruited to add nucleotides once another TLS polymerase has added a nucleotide opposite the lesion. The ability of Polζ to carry out synthesis downstream of DNA lesions caused by UV-light and chemical mutagens (Prakash et al., 2005) is important in maintaining genome integrity and preventing cancer (Lange et al., 2011; Sharma et al., 2013). Because Polζ can extend from both correct and incorrect nucleotides opposite from DNA lesions, it also contributes to mutagenic TLS.

Although Polζ was discovered >40 years ago (Lemontt, 1971), there is still little or no structural understanding of how this TLS polymerase is organized. Polζ from S. cerevisiae was initially identified as a heterodimer consisting of the subunits Rev3 and Rev7 (Nelson et al., 1996). Rev3 is the catalytic subunit that belongs to the same B-family of Pols as Pol1, Pol2, and Pol3, the catalytic subunits of the high-fidelity eukaryotic replicative Pols,α,ε andδ, respectively (Johansson and Macneill, 2010; Johnson and O'Donnell, 2005). During replication, Polα primes the Okazaki fragments on the lagging DNA strand, which are then elongated by Polδ. Polε is believed to be the leading strand DNA polymerase (Nick McElhinny et al., 2008). Besides the catalytic subunits, these high fidelity polymerases in yeast also contain accessory subunits: Pol12, Pri1 and Pri2 in Polα; Dpb2, Dpb3 and Dpb4 in Polε; and Pol31 and Pol32 in Polδ (Johansson and Macneill, 2010; Johnson and O'Donnell, 2005). In mice, disruption of the Rev3 subunit of Polζ causes embryonic lethality (Prakash et al., 2005; Sharma et al., 2013). The Rev3 sequence differs from that of Pol1, Pol2 and Pol3 in containing a large insert that is the site of Rev7 binding (Fig. 1A). Rev7 both stabilizes and increases the activity of Polζ. Surprisingly, Polζ has been found recently to associate with Pol31 and Pol32, the accessory subunits of Polδ (Johnson et al., 2012; Makarova et al., 2012). A stable four subunit Rev3/Rev7/Pol31/Pol32 complex can be purified from yeast, which we refer to as Polζ-d to distinguish it from the traditional Polζ heterodimer (Johnson et al., 2012). Importantly, the Pol31 and Pol32 subunits have been shown to be essential for Polζ function in vivo, and in vitro they increase the catalytic activity of Polζ between threefold and tenfold (depending on the lesion) (Johnson et al., 2012; Makarova et al., 2012). The Pol31/Pol32 sub-complex associates with Polζ via an interaction between the Rev3 C-terminal domain (CTD) and Pol31 (Baranovskiy et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2012; Makarova et al., 2012). The Rev3 CTD contains two cysteine-rich metal-binding motifs, CysA and CysB, analogous to the motifs at the C-termini of Pol1, Pol2, and Pol3. Thus, in subunit composition and structural complexity, Polζ-d resembles the high-fidelity replicative Polsα, ε, andδ. The fact that it shares the same accessory subunits (Pol31 and Pol32) as Polδ raises questions as to how the activities of the two polymerases are coordinated during lesion bypass.

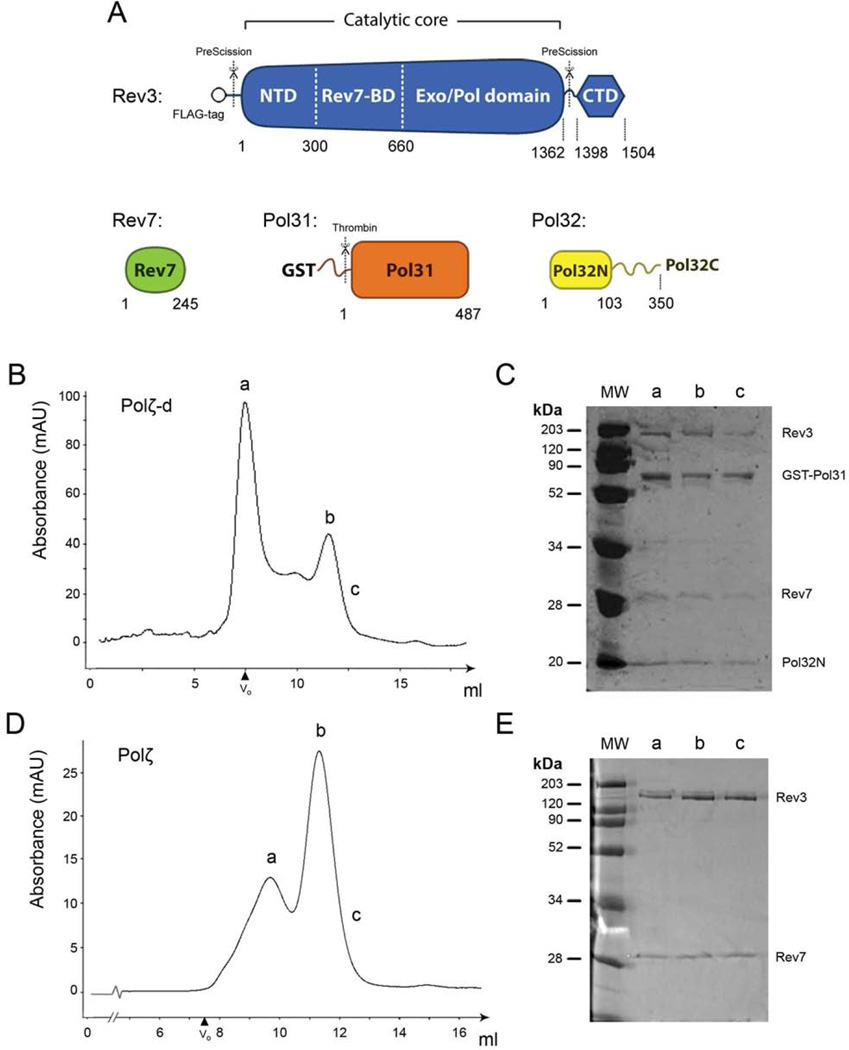

Figure 1. Purification of Polζ and Polζ-d complexes.

A. Scheme of the proteins and domains of the Polζ and Polζ-d complexes used in this study. Numbers indicate the delimiting residues. The Rev3 catalytic core is composed of the N-terminal domain (NTD), the Rev7 binding domain (Rev7-BD) and the Exo/Pol domain. The Rev3 C-terminal domain (CTD) is joined to the catalytic core by a flexible region. Pol32N is composed of the first 103 N-terminal amino acid residues of Pol32. “PreScission” and “Thrombin” indicate protease cleavage sites. B. Gel filtration elution profile of Polζ-d over a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column. The exclusion volume at 7.5 ml is indicated as Vo. The first and second peaks of the chromatogram are labeled as ‘a’ and ‘b’, while ‘c’ indicates the slope of the second peak. C. SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie blue staining of this peak reveals that Polζ-d is a stable complex of the subunits Rev3:Rev7:Pol31-GST:Pol32N. D. Gel filtration elution profile of Polζ over a Superdex 200 10/300 size exclusion column. Peaks are labeled as described in panel B. E. The SDS-PAGE analysis of this peak shows that Polζ forms a stable Rev3:Rev7 complex. Aliquots of the top fractions of peaks ‘b’ were used for single particle EM analysis for both samples.

Current structural information on Polζ (or Polζ-d) is limited to structures of human Rev7 in complex with a short peptide (residues 1875–1895) from human Rev3 and a structure of the human counterpart of Pol31 (p50) in complex with the N-terminal domain of Pol32 (p66N) (Baranovskiy et al., 2008; Hara et al., 2010). To understand how Polζ and Polζ-d are assembled into functional DNA polymerases, we undertook electron microscopy (EM) analyses of the two complexes. We present here the first 3-D models of yeast Polζ-d and Polζ, showing how the catalytic and accessory subunits are organized relative to each other. We show that Polζ-d has a bilobal architecture resembling the high fidelity replicative Pols, and that Pol32 lies in close proximity to Rev7. We discuss the implications of our findings for the role of Polζ in DNA damage bypass.

Results

Purification and EM analysis of Polζ-d and Polζ complexes

To purify the four-subunit Polζ-d complex we co-transformed plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged Rev3 (residues 1–1504), Rev7 (residues 1–245), GST-tagged Pol31 (residues 1–487) and Pol32N (residues 1–103) in S.cerevisiae cells (Fig. 1A). The FLAG-and GST-tags were engineered to be cleaved with PreScission and thrombin protease, respectively, and Pol32N was designed to express only the N-terminal domain of Pol32 (residues 1–103) that interacts with Pol31. The unstructured C-terminal tail of Pol32 (residues 104–350) that contains a proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) interaction motif was omitted from the construct. The Polζ-d heterotetramer was first purified over a Glutathione Sepharose (GST) column and then over an anti-FLAG agarose column. The FLAG- and GST-tags were not cleaved and the complex was concentrated and further purified over a Superdex-200 gel filtration column. SDS-PAGE analysis of peak ‘b’ fraction indicated a complex consisting of Rev3, Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32N (Fig. 1B & C). To prepare the Polζ heterodimer (Rev3/Rev7) for EM analysis, we separated it from partially purified Polζ-d. We adopted this procedure because expression of Rev3/Rev7 in the absence of Pol31/Pol32 is poor and the complex tends to aggregate. Thus, following the partial purification of Polζ-d over the GST column (described above), ion exchange chromatography was used to separate the Rev3/Rev7 heterodimer from the Pol31/Pol32N subcomplex. The Rev3/Rev7 heterodimer was then further purified over a Superdex-200 gel filtration column (Fig. 1D & E).

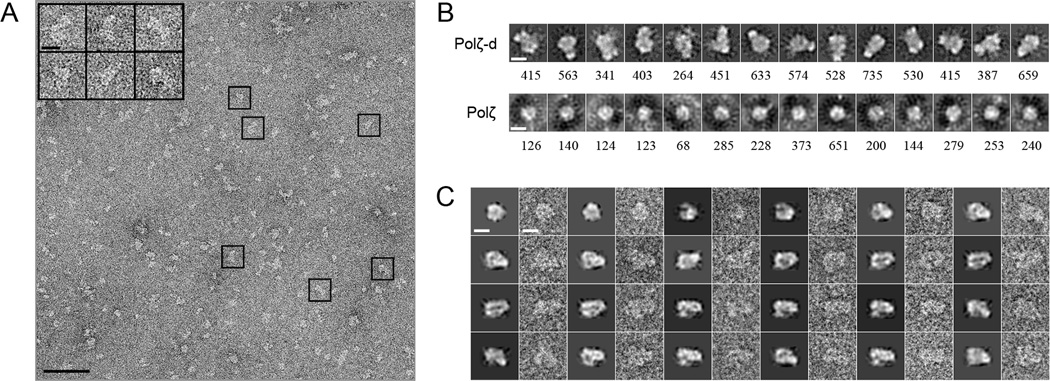

Gel-filtered samples of Polζ-d and Polζ were used to prepare the EM grids. Due to the relatively small size of both Polζ-d and Polζ, we imaged the specimens embedded in negative stain to ensure sufficient contrast (Ohi et al., 2004). Figure 2A displays a representative field view of negatively stained Polζ-d showing abundant elongated particles. Approximately 56,000 single images of Polζ-d particles and 69,000 of Polζ were automatically selected using EMAN2 (Tang et al., 2007), and then subjected to iterative rounds of reference-free classification and heterogeneity analysis using 2D maximum likelihood (MLF2D) (Scheres et al., 2005). The MLF2D averages for Polζ-d revealed (Fig. 2B) an elongated bilobal structure, that is reminiscent of the bilobal architecture previously determined for the Pol1–Pol12 complex (Klinge et al., 2009) and presumably represent side view projections of the Polζ-d complex rotating along its longitudinal axis. Consistent with the lower molecular weight of the Polζ heterodimer (185 KDa), the MLF2D averages for this complex revealed smaller globular particles, which correspond with projections of the larger of the two lobes observed for the Polζ-d heterotetramer. Further support for this interpretation was obtained by comparative KerDenSOM heterogeneity analysis (Pascual-Montano et al., 2001) between selected particle images of Polζ and Polζ-d masked around the large lobe (Fig. S1).

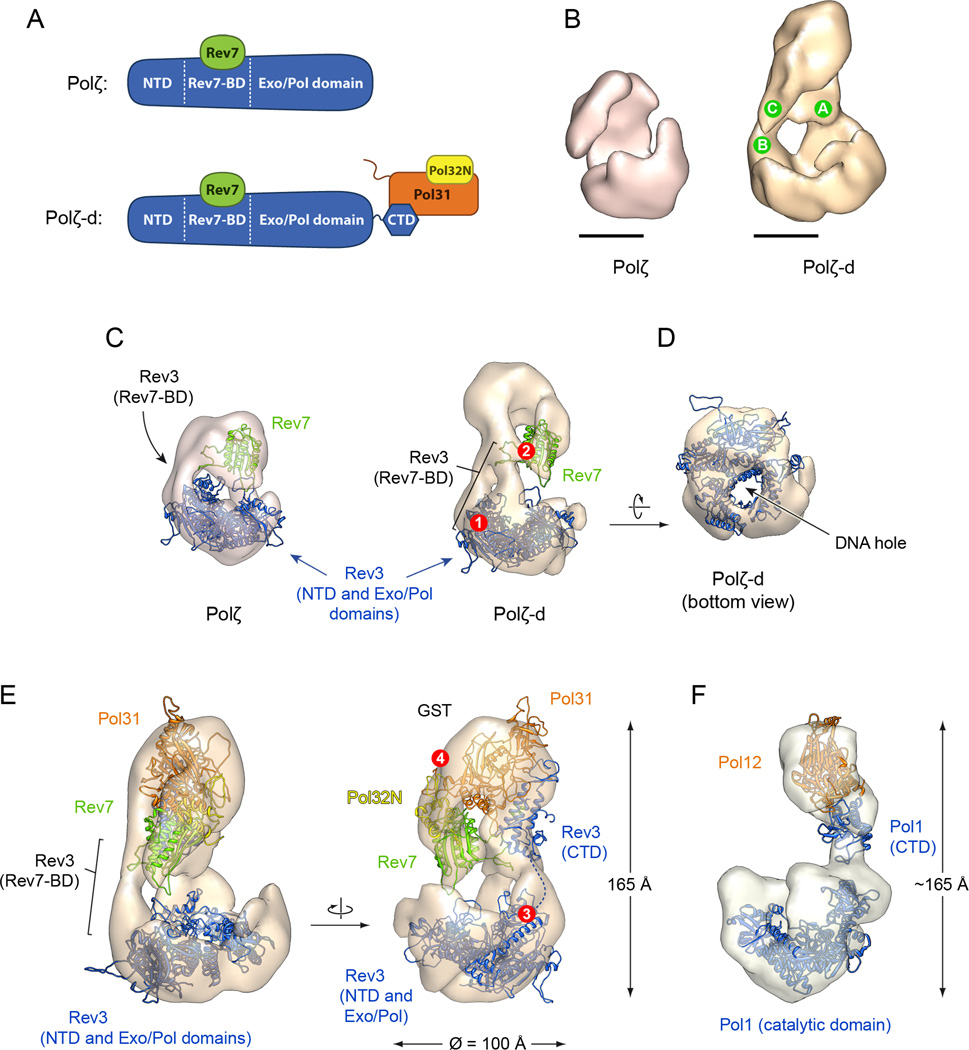

Figure 2. EM and image processing.

A. EM field view of negatively stained Polζ-d. Representative particle images are boxed. Scale bars indicate 50 nm in the EM field and 100 Å in the boxed particles. B. ML representative classes obtained during the iterative rounds of 2-D processing and classification of the raw particle images of the Polζ-d heterotetramer and the Polζ heterodimer. The number of particles included in each class is shown below every image. Masks were omitted in this analysis. Scale bars represent 100 Å. C. Comparison between projections of the final 3-D reconstruction of Polζ-d and raw single particle images. Every couple of images corresponds to a projection of the masked volume (the first image) and a corresponding single particle image (the second image). Scale bars represent 100 Å. See also Figures S1 and S2.

As a result of our MLF2D analysis a subset of approximately 15,000 particle images of the Polζ-d heterotetramer and 2,000 of the Polζ heterodimer were employed for 3-D reconstruction and refinement using Xmipp (Scheres et al., 2008). Projections of the reconstruction of Polζ-d correspond closely with individual particle images (Fig. 2C), indicating consistency between the reconstructed structure and the particle dataset. Based on the 0.5 criterion of the Fourier ring correlation (FRC), the final structures of Polζ-d heterotetramer and Polζ heterodimer were determined to resolutions of 23 and 25 Å, respectively (Fig. S2).

Polζ-d has a two-lobe architecture with separate catalytic and regulatory modules

The 3-D reconstruction of Polζ-d was rendered a threshold that includes a volume of 344,000Å3 corresponding to a molecular weight (determined using an average protein density of 0.856 Da/Å3 (Fischer et al., 2004)) of ~298 kDa, in agreement with the mass of the Polζ-d heterotetramer. The EM map revealed an elongated bilobal structure, in which two “stems” at the back of the structure connect the small upper lobe with the large lower lobe (Fig. 3B, right panel; stems labeled as green circles A and B). There is also a prominent “protrusion” at the front of the small lobe that does not connect with the large one (labeled as a green circle C in the right panel of Fig. 3B). The overall dimensions of the large lobe in Polζ-d are consistent with the molecular weight of Rev3 (173 KDa), while the small lobe has a size consistent with the combined mass of Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32N (total mass of 122 KDa). Due to the lower molecular weight of Polζ and the significantly lower number of particles used for its 3D reconstruction, the EM map of Polζ was of lower quality relative to that of Polζ-d. However, the density features shared by Polζ-d and Polζ (Fig. 3B) confirm that the large lobe corresponds to the catalytic subunit Rev3. The density region corresponding to the protrusion at the front of Polζ-d heterotetramer is also apparent in the Polζ heterodimer, indicating that it likely represents Rev7. Consistent with the absence of Pol31 and Pol32 subunits in the Polζ heterodimer, the major part of the density in the small lobe of the Polζ-d heterotetramer is missing in the Polζ heterodimer.

Figure 3. Structures of Polζ and Polζ-d.

A. Schema depicting the modeled regions of the different subunits of Polζ and Polζ-d. B. Front views of the EM reconstructions of Polζ and Polζ-d. Consecutive letters A, B and C inside green circles mark the two stems that separate the big and small lobes, and the protrusion extending from the small lobe. Scale bars represent 50 Å. C. Fitting of the modeled domains of Rev3 catalytic core (in blue: residues 1–300 and 660–1362) and Rev7 (in green) into the EM maps. Both maps are rotated 90° along the z axis relative to the orientations in B. Residues flanking Rev7-BD (330 and 660, labeled with a red circle #1) are located in proximity to the assigned density of Rev7-BD. The β-strands of Rev7 responsible of the interactions with Rev3 (red circle #2) are facing the Rev7-BD assigned density. D. Bottom view of the Polζ-d EM map, showing a hole in the density that matches the DNA hole of Rev3. E. Fitting of the four subunits into the EM map of the Polζ-d heterotetramer. The height of Polζ-d was measured as 165 Å. The residue 1362 of Rev3 is labeled (red circle #3), and the location of the 32 next amino acid residues that separates the CTD (residues 1398–1504) of the catalytic core, is represented by a dashed line. The density assigned to GST is in proximity to the N-term residues of Pol31 (red circle #4). F. EM structure and subunit architecture of Polα in a similar orientation to our reconstruction (Klinge et al., 2009). Homologous Pol31 and Pol12 (PDB id: 3FLO), and Rev3 and Pol1 (PDB id: 2VWJ), are depicted in panels E and F using identical colors. Both Polζ and Polα share a similar architecture with comparable dimensions. See also Figures S3 and S4 and Movie S1.

A structural model of Polζ-d

In order to produce a structural model of yeast Polζ-d consistent with our 3-D reconstruction we manually fitted homology models of all the subunits to match the corresponding regions of the EM map. To guide the placement and orientation of the subunits in the map we used constraints derived from the comparison of the EM maps of Polζ-d and Polζ, complemented with additional constraints derived from published structural and biochemical data. We employed comparative protein structure modeling with the program Modeller (Fiser and Sali, 2003) to build homology models for yeast Rev3, Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32N. The modeled regions of the different subunits are schematized in Figure 3A. The structure of Pol3 catalytic core of yeast Polδ (Swan et al., 2009) served as a template for the catalytic core of yeast Rev3. The Rev3 CTD was modeled on the basis of the structure of yeast Pol1 CTD in complex with Pol12 (Klinge et al., 2009). In addition, the crystal structures of human Rev7 (Hara et al., 2010) and the p50–p66N heterodimer (Baranovskiy et al., 2008) served as templates to build the models of yeast Rev7 and Pol31–Pol32N, respectively.

The catalytic core of yeast Rev3 is much larger than the Rev7 subunit and could fit with a high cross correlation (CC) coefficient of 0.86 into the large lobe of Polζ-d (Fig. 3C, right panel). The orientation of the catalytic core was inferred by matching a characteristic “DNA hole”, also observed in the center of the structure of Pol3, with the only hole at the bottom of the large lobe of the EM map (Fig. 3D). Consistently, the Rev3 catalytic core also fitted well and with the same orientation into the corresponding density in the Polζ heterodimer (Fig. 3C, left panel). Rev7 fitted (CC coefficient = 0.81) into the density region suspended over Rev3 in both the Polζ-d heterotetramer and the Polζ homodimer.

The crystal structure of only a short peptide region (21 amino acids) from human Rev3, which interacts with Rev7, has been elucidated (Hara et al., 2010). Due to the lack of an appropriate structural template, we could not model the corresponding Rev7-interacting region of yeast Rev3 (residues 300–660) in Polζ and Polζ-d EM models. However, the orientation of Rev7 in our model positions the Rev3 binding site in Rev7 (red circle 2 in Fig. 3C) ~50 Å away from residues 299 and 661 in Rev3 (red circle 1 in Fig. 3C), in the direction of the first stem (labeled as green circle B in Fig. 3B) connecting the large lobe with the small lobe in the Polζ-d EM map. We suggest that this density along the first stem corresponds to the unmodeled insert in Rev3 (residues 300–660) that connects to Rev7. Based on recent biochemical studies, the Pol31/Pol32 sub-complex associates with Rev3 via a direct interaction between the Rev3 CTD and Pol31. We modeled the Pol31/Pol32 complex based on the crystal structure of p50/p66N complex (Baranovskiy et al., 2008), the human counterparts of Pol31 and Pol32, and the interaction between Rev3 CTD and Pol31 was modeled on the crystal structure of Pol1 CTD/Pol12 complex (Klinge et al., 2009). The modeled Pol31–Pol32-CTD structure accounts for the major portion of the EM density (CC coefficient = 0.87) in the small lobe of Polζ-d (Fig. 3E). The Rev3 CTD region of Rev3 connects to the catalytic core via a 36 amino acid long linker, beginning at amino acid 1362 (red circle 3 in Fig. 3E). We suggest that this unmodeled linker corresponds to the 2nd stem (labeled as green circle A in Fig. 3B) of density connecting the upper lobe with the larger lower lobe in the Polζ-d EM map.

Taken together, the structural model of Polζ-d shown in Figure 3 accounts for a majority of the EM density of the 3-D reconstruction of Polζ-d (CC coefficient = 0.86). The model suggests a bilobal architecture for Polζ-d with separate catalytic and regulatory modules. The accessory subunits Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32 form the regulatory module that connects to the catalytic subunit Rev3 at two different sites via interaction with Rev7 and Pol31, respectively. The Pol31/Pol32 subunits hover above the Rev3 catalytic core, raising the possibility that they may interact with the DNA (Fig. S3).

Interactions with the DNA

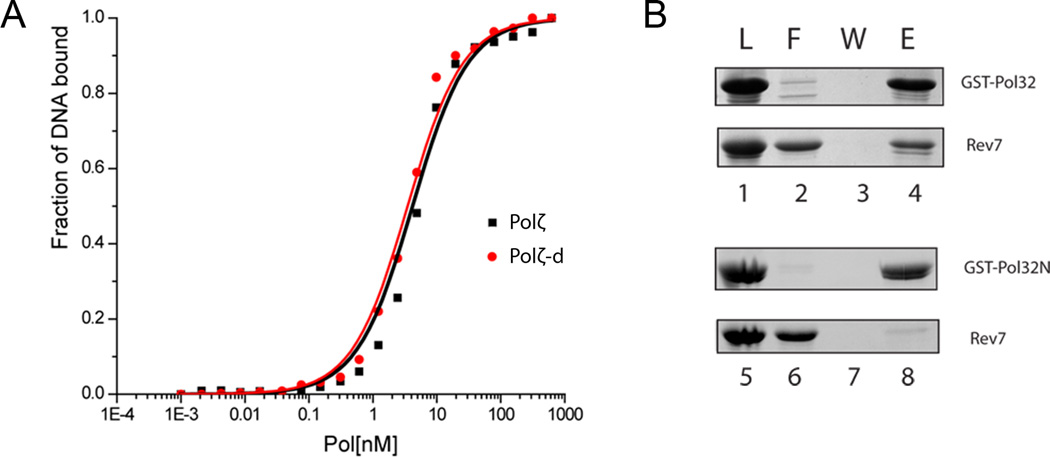

To test whether the Pol31/Pol32 subunits in Polζ-d increase the affinity of Polζ for DNA, we compared the binding of Polζ-d and Polζ to a fluorescein-labeled 40-nt/45-nt primer/template using fluorescence anisotropy. The length of the primer/template was based on the Polζ-d structural model, as the number of nucleotides required to span the catalytic (Rev3) and regulatory (Rev7/Pol31/Pol32) modules. Figure 4A shows that the Polζ homodimer (Rev3/Rev7) and Polζ-d heterotetramer (Rev3/Rev7/Pol31/Pol32N) bind the primer/template with similar Kd of ~4 nM. Together, these data suggest that despite the proximity of Pol31 and Pol32N to the modeled DNA in the Polζ-d heterotetramer, these subunits do not contribute significantly to DNA binding.

Figure 4. Biochemical assays.

A. DNA binding activity of Polζ and Polζ-d. Binding of Polζ-d and Polζ to a 40/45 duplex DNA as monitored by changes in anisotropy during the titration. Fitting of the data yields a Kd of 3.5 ± 0.25 nM for the Polζ-d heterotetramer (red line) and a Kd of 4.2 ± 0.40 nM for the Polζ heterodimer (black line). The 6-FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) labeled oligonucleotides were excited at 490 nm and the resulting emission was passed through a 520 nm cutoff filter on a Beacon 2000 fluorescence polarization system. The DNA concentration was fixed at 2 nM. Protein concentration was varied from 10 pM to 600 nM. B. Physical interaction of Rev7 with Pol32 and Pol32N. Glutathione-sepharose bead bound Pol32 (Lanes 1–4) or Pol32N (Lanes 5–8) was mixed with Rev7 and pull-down assays were dome as described in experimental procedures. Fractions load (L, lanes 1 and 5), flow through (F, 2 and 6), wash (W, 3 and 7) and elution (E, 4 and 8) were resolved on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, followed by Coomassie blue R-250 staining. Rev7 binds to full length Pol32 but not to the C-terminally truncated Pol32 (Pol32N). See also Figure S3 and Movie S1.

Interactions between Rev7 and Pol32

Intriguingly, Rev7 and Pol32N are in close spatial proximity in our Polζ-d model, raising the possibility that Rev7 and Pol32 physically interact. We tested this idea via a GST-pulldown assay. Briefly, GST-Pol32 and GST-Pol32N (C-terminally truncated Pol32, 1–104 a) were bound to GST beads and individually mixed with Rev7. After incubation and extensive washing, the bead bound proteins were eluted and resolved on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, followed by Coomassie blue staining. Indeed, figure 4B shows that Rev7 binds to full length Pol32 but not to the C-terminally truncated Pol32 (Pol32N).

Comparison to Polα

Despite differences in subunit composition and stoichiometry, a comparison between the EM structures of Polζ-d and high-fidelity Polαcomplexes (Klinge et al., 2009; Nunez-Ramirez et al., 2011), reveals a common architecture (Fig. 3F). Both polymerases share a bilobal configuration with very similar dimensions along the longitudinal axis, and separate catalytic and regulatory modules. In both polymerases, a short linker connects the polymerase catalytic core to its CTD and the respective B–accessory subunit, Pol31 in Polζ-d and Pol12 in Polα. In Polα structures, this linker has been suggested to be the source of flexibility between the regulatory and catalytic modules (Klinge et al., 2009). A study of the conformational heterogeneity of the Pol1–Pol12 complex, for example, using MLF3D revealed that the CTD–Pol12 module could sample a range of positions relative to the catalytic core. Indeed, this inter-modular flexibility appears to be a general property of replicative B-family polymerases. An EM 3-D model of the yeast Polε holoenzyme suggests analogous flexibility between the catalytic subunit (Pol2) and the accessory subunits (Dpb2, Dpb3 and Dpb4) (Asturias et al., 2006). Also, small-angle X-ray scattering analysis of the yeast Polδ holoenzyme, which shares the Pol31–Pol32 subunits with Polζ, suggests high conformational variability of the regulatory module with respect to the catalytic domain (Jain et al., 2009). To examine the conformational heterogeneity in the Polζ-d heterotetramer, we performed the MLF3D procedure on the EM data but did not observe significant variation in the relative positions of the catalytic and regulatory modules (data not shown).

Discussion

We present here the first 3-D structural models of Polζ and Polζ-d, based on EM imaging and single-particle reconstruction. We show that Polζ has a globular-like structure, whereas Polζ-d has an elongated bilobal architecture. The large lobe of Polζ-d can be fitted with the Rev3 catalytic core and the smaller lobe with the accessory subunits Rev7, Pol31, Pol32N, as well as Rev3 CTD. There are two stems of density connecting the lobes, which appear to derive from the insert in Rev3 (residues 300–660) that binds Rev7 and the linker connecting the catalytic core of Rev3 to the CTD/Pol31/Pol32N substructure. The extended bilobal architecture of Polζ-d is highly reminiscent of high fidelity replicative Pols α and δ (Jain et al., 2009; Klinge et al., 2009; Nunez-Ramirez et al., 2011). One difference is that whereas the catalytic and regulatory modules in Polα and Polδ are flexibly tethered (Jain et al., 2009; Klinge et al., 2009), they seem to be more rigidly associated in Polζ-d. This may reflect the fact that two modules in Polζ-d are additionally tethered via Rev3– Rev7 interactions. In Polα, the flexibility between the modules is thought to be important in the transfer of the RNA primer from the active site of its primase Pri1/Pri2 subunits on one module to the active site of the polymerase Pol1 subunit on the other module (Nunez-Ramirez et al., 2011). In Polδ, flexibility may be important when there is a change in DNA direction as, for example, during a switch in the DNA primer from the polymerase to the exonuclease active site of Pol3 during DNA synthesis. In contrast, because there is no equivalent change in DNA direction when Polζ-d extends from DNA lesions this may partially obviate the need for inter-module flexibility of the type observed in Polα and Polδ.

Rev7 and Pol32N are in close spatial proximity in our Polζ-d model. We tested whether Rev7 and Pol32 physically interact via a GST-pulldown assay. Intriguingly, Rev7 binds to full length Pol32 but not to the C-terminally truncated Pol32 (Pol32N). From secondary structure analysis, the C-terminal residues of Pol32 (104–350) lack secondary structure but based on our Polζ-d model and pulldown assay appear capable of physically interacting with Rev7. This Rev7 and Pol32 interaction may be one reason why Pol32 is indispensable for Polζ-d complex formation. Thus, whereas Pol3, the catalytic subunit of Polδ, can form a stable complex with Pol31 in the absence of Pol32, Rev3/Rev7 is less stable without Pol32 (Johnson et al., 2012; Makarova et al., 2012).

Pol31 and Pol32 are essential for Polζ function in vivo, and in vitro they increase the catalytic activity of Polζ between threefold and tenfold (Johnson et al., 2012; Makarova et al., 2012). Since Pol31 contains an oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide (OB) fold and an inactive phosphodiesterase domain it could, in principle, help to increase the affinity of Polζ for DNA (Baranovskiy et al., 2008); however, we show here that Polζ and Polζ-d bind DNA with similar Kds. Pol31 and Pol32 greatly increase the stability of Rev3/Rev7 complex as indicated from the high resistance of Polζ-d to salt concentrations up to 1 M NaCl (Johnson et al., 2012). The increase in stability is also reflected in effects on catalysis, as kinetic analysis of Polζ and Polζ-d shows that increase in the catalytic efficiency of Polζ-d compared to Polζ is primarily due to an increase in kcat value (Johnson et al., 2012).

Intriguingly, a deficiency in Rev1 confers a similar phenotype as a deficiency in Polζ, suggesting an interaction between the two proteins (Lawrence, 2004). Indeed, in vertebrates, Rev7 has been shown to physically associate the C-terminal region of Rev1 (Murakumo et al., 2001), and a number of crystal structures have provided the molecular basis of this interaction (Kikuchi et al., 2012; Wojtaszek et al., 2012). Figure S4 shows the C-terminal region of human Rev1, composed of 4 helices, docked against Rev7 in our yeast Polζ-d model. Notably, the Rev1 C-terminal region extends from the Polζ-d core in an accessible position to engage other TLS polymerases in mammalian cells.

In conclusion, despite the critical role of Polζ (or Polζ-d) in eukaryotic DNA damage response, there has been little structural information on the architecture of the complex. We present here the first 3-D structural models of Polζ and Polζ-d, showing how the catalytic and accessory subunits are organized relative to each other for DNA damage bypass in eukaryotic cells.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Expression and Purification

The Rev3/Rev7 complex in the absence of Pol31/Pol32 expresses poorly and tends to aggregate. To overcome this hurdle we engineered constructs of the enzyme carrying several purification tags and specific protease sites, which would allow us to purify both Polζ-d and Polζ from the “same” preparation. Briefly, plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged Rev3 (residues 1–1504), Rev7 (residues 1–245), GST-tagged Pol31 (1–487 residues) and Pol32N (residues 1–103) were co-transformed into yeast cells. The FLAG-tag was engineered to be cleaved with the PreScission protease; the GST-tag was linked to Pol31 via a 12 amino acid long linker containing a thrombin protease site; Rev3 included an additional PreScission protease site in between the catalytic core and the CTD domain; and Pol32N was designed to express only the N-terminal domain of Pol32 (residues 1– 103) that interacts with Pol31. The Polζ-d heterotetramer was first purified over a GST column and then over an anti-FLAG agarose column. The GST and FLAG tags were not cleaved and the complex was concentrated and further purified over a Superdex-200 Gel Filtration column. The FLAG tag was not removed because proteolysis with PreScission would have also removed the region corresponding to Pol31/Pol32/CTD; the GST tag was not removed because thrombin is a promiscuous protease and the presence of a cryptic thrombin cleavage site in Rev3 (residues 393–398). SDS-PAGE analysis of peak b fraction indicated a homogeneous complex of Rev3, Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32N (Fig. 1B & C). To prepare the Polζ heterodimer (Rev3/Rev7) for EM analysis, we separated it from Polζ-d, which was first partially purified over the GST column (described above), and then incubated with PreScission protease to remove the CTD domain of Rev3 together with Pol31/Pol32N. Following the PreScission protease treatment ion exchange chromatography was used to separate the Rev3/Rev7 heterodimer from the CTD/Pol31/Pol32N subcomplex. The Rev3/Rev7 heterodimer was then further purified over a Superdex-200 gel filtration column (Fig. 1D & E).

DNA Binding Experiments

DNA binding experiments were performed with a 6-FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) – labeled 45-mer/40-mer template/primer (2nM) on a Panvera Beacon 2000 fluorescence polarization system, with increasing concentrations of Polζ-d and Polζ complexes (10 pM to 625 nM).

Physical Interaction of Rev7 with Pol32 and Pol32N

GST beads bound Pol32 or Pol32N were individually mixed with Rev7. The beads were spun down, washed, and the bound proteins eluted with an SDS buffer.

Electron Microscopy and 3-D Reconstruction

Negatively stained Polζ-d and Polζ were imaged on a Jeol 2100F FEG transmission electron microscope at 200 kV under low dose conditions, using a 2k×2k pixel CCD Tietz camera at the equivalent calibrated magnification of 63,450 × and −1.5 µm defocus. Particle images of Polζ-d and Polζ were automatically selected using EMAN2 (Tang et al., 2007), and then subjected to iterative rounds of reference-free classification and heterogeneity analysis using 2D maximum likelihood (MLF2D) (Scheres et al., 2005). 3D reconstruction was carried out using the software Xmipp (Scheres et al., 2008). Fitting, visualization and 3-D image generation were performed using UCSF Chimera (Goddard et al., 2007).

Modeling and protein interactions

The homology models for yeast Rev3, Rev7, Pol31 and Pol32 were built by comparative protein structure modeling. The approximate location and orientation of the DNA was inferred by comparison with the DNA-Pol3 complex of the DNA polymerase Polδ from yeast (PDB id: 3IAY).

Accession Numbers

The EM map of Polζ-d is deposited in EMDB (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/) The accession number is EMD-2409

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

First view of the architecture of DNA Polymerase ζ.

Enzyme has an elongated structure with separate catalytic and regulatory lobes.

The accessory Pol32 and Rev7 subunits are in close spatial proximity.

The structure shows why Pol32 and Rev7 are needed for complex formation.

Acknowledgments

Access to electron microscopy instrumentation was provided by the New York Structural Biology Center, a STAR center supported by the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research. Computing resources needed for this work were provided in part by the scientific computing facility of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. L.P. was supported by grant CA107650 from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asturias FJ, Cheung IK, Sabouri N, Chilkova O, Wepplo D, Johansson E. Structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase epsilon by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:35–43. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranovskiy AG, Babayeva ND, Liston VG, Rogozin IB, Koonin EV, Pavlov YI, Vassylyev DG, Tahirov TH. X-ray structure of the complex of regulatory subunits of human DNA polymerase delta. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3026–3036. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranovskiy AG, Lada AG, Siebler HM, Zhang Y, Pavlov YI, Tahirov TH. DNA polymerase delta and zeta switch by sharing accessory subunits of DNA polymerase delta. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17281–17287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.351122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer H, Polikarpov I, Craievich AF. Average protein density is a molecular-weight-dependent function. Protein Sci. 2004;13:2825–2828. doi: 10.1110/ps.04688204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser A, Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:461–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Hashimoto H, Murakumo Y, Kobayashi S, Kogame T, Unzai S, Akashi S, Takeda S, Shimizu T, Sato M. Crystal structure of human REV7 in complex with a human REV3 fragment and structural implication of the interaction between DNA polymerase zeta and REV1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12299–12307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Hammel M, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Structural insights into yeast DNA polymerase delta by small angle X-ray scattering. J Mol Biol. 2009;394:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E, Macneill SA. The eukaryotic replicative DNA polymerases take shape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, O'Donnell M. Cellular DNA replicases: components and dynamics at the replication fork. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:283–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. Pol31 and Pol32 subunits of yeast DNA polymerase delta are also essential subunits of DNA polymerase zeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12455–12460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206052109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, Hara K, Shimizu T, Sato M, Hashimoto H. Structural basis of recruitment of DNA polymerase zeta by interaction between REV1 and REV7 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33847–33852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge S, Nunez-Ramirez R, Llorca O, Pellegrini L. 3D architecture of DNA Pol alpha reveals the functional core of multi-subunit replicative polymerases. Embo J. 2009;28:1978–1987. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange SS, Takata K, Wood RD. DNA polymerases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:96–110. doi: 10.1038/nrc2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CW. Cellular functions of DNA polymerase zeta and Rev1 protein. Adv Protein Chem. 2004;69:167–203. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)69006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemontt JF. Mutants of yeast defective in mutation induced by ultraviolet light. Genetics. 1971;68:21–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/68.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarova AV, Stodola JL, Burgers PM. A four-subunit DNA polymerase zeta complex containing Pol delta accessory subunits is essential for PCNA-mediated mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11618–11626. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakumo Y, Ogura Y, Ishii H, Numata S, Ichihara M, Croce CM, Fishel R, Takahashi M. Interactions in the error-prone postreplication repair proteins hREV1, hREV3, and hREV7. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35644–35651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102051200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JR, Lawrence CW, Hinkle DC. Thymine-thymine dimer bypass by yeast DNA polymerase zeta. Science. 1996;272:1646–1649. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nick McElhinny SA, Gordenin DA, Stith CM, Burgers PM, Kunkel TA. Division of labor at the eukaryotic replication fork. Mol Cell. 2008;30:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Ramirez R, Klinge S, Sauguet L, Melero R, Recuero-Checa MA, Kilkenny M, Perera RL, Garcia-Alvarez B, Hall RJ, Nogales E, et al. Flexible tethering of primase and DNA Pol alpha in the eukaryotic primosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8187–8199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi M, Li Y, Cheng Y, Walz T. Negative Staining and Image Classification - Powerful Tools in Modern Electron Microscopy. Biol Proced Online. 2004;6:23–34. doi: 10.1251/bpo70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Montano A, Donate LE, Valle M, Barcena M, Pascual-Marqui RD, Carazo JM. A novel neural network technique for analysis and classification of EM single-particle images. J Struct Biol. 2001;133:233–245. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash S, Johnson RE, Prakash L. Eukaryotic Translesion Synthesis DNA Polymerases: Specificity of Structure and Function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:317–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH, Nunez-Ramirez R, Sorzano CO, Carazo JM, Marabini R. Image processing for electron microscopy single-particle analysis using XMIPP. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:977–990. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres SH, Valle M, Nunez R, Sorzano CO, Marabini R, Herman GT, Carazo JM. Maximum-likelihood multi-reference refinement for electron microscopy images. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Helchowski CM, Canman CE. The roles of DNA polymerase zeta and the Y family DNA polymerases in promoting or preventing genome instability. Mutat Res. 2013;743–744:97–110. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan MK, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Structural basis of high-fidelity DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase delta. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:979–986. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek J, Lee CJ, D'Souza S, Minesinger B, Kim H, D'Andrea AD, Walker GC, Zhou P. Structural basis of Rev1-mediated assembly of a quaternary vertebrate translesion polymerase complex consisting of Rev1, heterodimeric polymerase (Pol) zeta, and Pol kappa. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33836–33846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.