Abstract

Protein kinase signaling regulates human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) fate, yet little is known about critical pathway substrates. To address this, we have developed and applied a large-scale, empirically-optimized phosphopeptide affinity enrichment strategy with high-throughput 2D LC-MS/MS screening to evaluate the phosphoproteome of an isolated human CD34+ HSPC population. We first used hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) as a first dimension separation to separate and simplify protein digest mixtures into discrete fractions. Phosphopeptides were then enriched offline using TiO2-coated magnetic beads and subsequently detected online by C18 reverse phase nanoflow HPLC using data-dependent MS/MS High-Energy Collision-activated Dissociation (HCD) fragmentation on a high performance Orbitrap hybrid tandem mass spectrometer. We identified 15533 unique phosphopeptides in 3574 putative phosphoproteins. Systematic computational analysis revealed biological pathways and phosphopeptides motifs enriched in CD34+ HSPC that are markedly different from those observed in an analogous parallel analysis of isolated human T cells, pointing to the possible involvement of specific kinase-substrate relationships within activated cascades driving hematopoietic renewal, commitment and differentiation.

Keywords: human, hematopoietic, stem cell, signaling, phosphoprotein, phosphopeptide, chromatography, enrichment, tandem mass spectrometry

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells can self-renew or differentiate into progenitors of mature blood cells [1,2]. Peripheral human CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell populations (HSPC) derived from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood are used in clinical transplantation to restore the entire hematopoietic system [3]. Both gene expression and proteomic profiling of isolated HSPC populations have been widely studied in the past several years [4–7]. Through those studies, human hematopoietic cell fate has been shown to be tightly regulated by the differential activity of different signaling pathways [7]. However, unbiased global phosphoproteomic analysis of HSPC has not yet been reported [8] and relatively little is known about pathway substrates critical to cell fate decisions.

Due to the complexity of biological systems and the low abundance of many phosphoproteins under physiologic conditions, advanced methods for the selective enrichment, separation and detection of phosphopeptides have been developed over the past decade. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is one of the most popular phosphopeptide enrichment methods. The surface of TiO2 is positively charged and can specifically absorb phosphorylated peptides. Coating magnetic beads with TiO2 enables easier separations and increases enrichment yields compared to agarose resins [9]. Yet TiO2 alone cannot enrich phosphopeptides exclusively because of the non-specific binding effect from acidic peptides.

Other popular methods for phosphopeptide separation include reverse phase (RP) high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), which is usually coupled online with tandem mass spectrometry detection (LC-MS/MS), and multi-dimensional HPLC separations[10], which are usually performed offline using ion-exchange resins [11,12]. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) is an emerging separation method that uses a hydrophilic stationary phase and a hydrophobic mobile phase to efficiently separate out polar analytes, such as phosphopeptides [13]. HILIC is increasingly being applied in proteomics due to its buffer compatibility with mass spectrometry and its orthogonality relative to reverse phase chromatography separations (RP) [14]. While both HILIC and strong cation exchange chromatography (SCX) can be used as first dimension separations prior to RP/LC-MS/MS. [15], SCX has a lower separation ability compared to HILIC since it just separates differently charged ion groups. Moreover, the eluate of HILIC columns can be directly injected into an RP/LCMS/MS system or used for further downstream phosphopeptide enrichment, whereas desalting is required in SCX since the salt used in the mobile phase is likely to depress phosphopeptide detection.

Once enriched, phosphopeptides must be identified. Tandem mass spectrometry has a level of sensitivity and flexibility that set it apart from other analytical methods used in the past to analyze phosphoproteins, and is increasingly being used for unbiased mapping of phosphorylation sites on large numbers of polypeptides. After measuring each ionized analyte (i.e. phosphopeptide) according to its experimentally observed mass to charge ratio (m/z) (during a precursor ion scan), a fragmentation pattern can be generated and recorded nearly simultaneously (during a fragment ion scan or MS/MS) usually allowing for both sequence identification and modification site determination. Traditionally, two complementary fragmentation techniques, collision activated dissociation (CAD) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD), have been used to sequence phosphopeptides using workhorse ion trap instruments[16]. However the fragments obtained from CAD of phosphoserine and phosphotheronine often show prominent neutral loss which affects database searching. In contrast, ETD is preferred when examining higher charge density ions.

Higher energy collision dissociation (HCD) is an emerging fragmentation technique for phosphoproteomic studies now available on the popular high-performance Orbitrap platform [12,17,18] . Unlike CAD or ETD, HCD can measure the full mass range of the fragment ions with high mass accuracy. As both HCD on the Orbitrap and CAD performed in triple quadruple instruments (QQQ-CAD) use high energy collisions to fragment ions, . they tend to show high overall similarity in the product ion patterns observed, which can be exploited in targeted proteomic studies to increase the sensitivity of absolute quantification assays [18]. We have now developed an efficient 2D HPLC separation procedure, using HILIC as a first step before magnetic bead-based TiO2 enrichment and nanoflow RP chromatography, followed by phosphopeptide identification by high resolution HCD fragmentation on an Orbitrap-Velos instrument. Here, we report the application of this platform for the unbiased integrative global analysis of signaling networks in isolated human CD34+ HSPC. We compare the phosphopeptides motifs and biological pathways that are differentially active in CD34+ HSPC with those found in an analogous in house study of human CD3+ T cells . The systematic computational analysis revealed distinct protein phosphorylation motifs, pathway and phosphoprotein function from CD34+ HSPC, which provide insights into kinase-substrate relationships that underlie hematopoietic stem cell fate decisions.

Materials and Methods

Cell purification and cell culture

Human CD34+ HSPCs from G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood of two different donors and CD3+ T lymphocytes from non-mobilized peripheral blood of a different donor were accessed through the donor program at the FHCRC Large Scale Cell Processing Core/Center for Excellence in Hematology. CD34+ cells were enriched using the Miltenyi CliniMacs system with Miltenyi CD34 affinity beads, while CD3+ T cells were isolated using CD3 capture beads. Flow cytometry verified that the purity of CD34+ cells was over 93% after enrichment. CD34+ HSPCs were thawed and expanded for 4 days in serum-free StemSpan SFEM medium (StemCell Technologies), supplemented 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco) and 100 ng/ml stem cell factor (SCF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), flt3 ligand (FL), thrombopoietin (TPO) to a density between 0.5-1.5 million cells/ml at 37 °C under 5% CO2. T cells were thawed and cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1X Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco), 1% sodium pyruvate (HyClone), and 55 nM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma).

Sample preparation

Both human CD34+ HSPC and CD3+ T cell were lysed in 1 mL ice-cold 8 M urea in the presence of protease inhibitor (Complete; Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor (PhosphoSTOP; Roche). After brief sonication and centrifugation, the soluble protein supernatants were separated from the insoluble debris. Protein concentrations were measured by Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). In total, we digested 2mg of human CD34+ HSPC protein, or 1mg of CD3+ T cell protein, equilibrated in 50mM NH4HCO3. Samples were reduced with 2.5mM DTT for 1 hour at room temperature (RT) then alkylated with 5mM iodoacetamide for 45 minutes in the dark at RT. Denatured polypeptides were digested with sequencing-grade trypsin (Promega) in solution using a protein to trypsin ratio of 50:1 after 3-fold sample dilution with additional 50mM NH4HCO3. After 4 hours, the proteins were diluted another 3 fold with 50mM NH4HCO3 containing additional trypsin, and continuously digested overnight. After acidification to 1% formic acid, the peptides were desalted on disposable Toptip C-18 columns (Glygen) and lyophilized to dryness.

Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography (first dimension separation)

A 2.0 × 150-mm 5μm particle TSKgel Amide-80 column (Tosoh Biosciences), plummed to an Agilent 1100 quaternary pump HPLC system, was used for initial extract separations. The mobile phase buffer A consisted of 98% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), while buffer B contains 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA. The peptides were solubilised with a 80% buffer A/20% buffer B and loaded at a flow rate of 250μL/min. The column was then eluted with a gradient of 20% to 40% buffer B from 3 minutes to 30 minutes followed by 40% to 100% buffer B for3 minutes, then 100% buffer B for 5 minutes and 100% to 20% for2 minutes and finally 20% buffer B for 10 minutes. During elution, fractions were collected in eppendorf tubes at 2 minute intervals, except for the last interval which was collected over 12 minutes. The 20 fractions, collected over a 50 minute run time, were lyophilized to dryness.

Metal chelate enrichment

TiO2 coated magnetic beads (Pierce) were equilibrated and used for phosphopeptide enrichment according to the manufacturers protocol. The peptides in each HILIC fraction were resuspended in 200μL 80% acetonitrile/2% formic acid before incubating with 10 μL TiO2 magnetic beads for 1 min. After placing the beads on a magnetic plate for 1 minutes, unbound supernatant was decanted. The beads were washed three times with 200μL binding buffer in the TiO2 magnetic beads kit. After final decanting, the beads were incubated for 10 min with 30 μL elution buffer in the TiO2 magnetic beads kit. Then the phosphopeptide eluate was carefully removed using a multichannel pipettor and dried prior to LC-MS/MS analysis.

Second dimension (reverse phase) separation and mass spectrometry analysis

Each peptide mixture were individually loaded onto a reverse phase micro-capillary liquid trap pre-column and separated on an analytical column using an EASY-nLC HPLC system (Proxeon). The trap was constructed in 25mm × 75μm i.d silica capillary packed with 5μm Luna C18 stationary phase (Phenomenex). The analytical column was constructed in a 100mm × 75μm i.d. silica capillary packed with 3μm Luna C18 stationary phase, with a fine tip pulled with a column puller (Sutter Instruments). The organic nanoflow gradient consisted of buffer A, composed of 5% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid, and buffer B, which contained 95% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. The separation was performed for 120 minutes at a flow rate of 300nL/min, with a gradient of 2% to 6% buffer B for 1 minute, followed by 6% to 24% buffer B for 89 minutes, 24% to 100% buffer B for 16 minutes, then 100% buffer B for 5 minutes, 100% to 0% buffer B for 1 minute and finally 0% buffer B for 8 minutes.

Eluted peptides were directly sprayed into an LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) with high energy collision dissociation (HCD) fragmentation method using a nanospray ion source (Proxeon). Ten ms/ms data-dependent scans in centroid mode were acquired simultaneously with one profile mode full scan mass spectra. The full scan was performed in 30,000 resolution, with an ion packet setting of 1exp6 for automatic gain control (AGC) and a maximum injection time of 250ms. The ms/ms scans were performed using 7,500 resolution, with 3exp4 AGC, 150ms maximum injection time, 0.1ms activation time and 40% normalized collision energy. A dynamic exclusion list was enabled to exclude a maximum of 500 ions over 30s.

Protein and peptide identification

RAW files were submitted for database searching using MaxQuant (version 1.3.0.5; http://maxquant.org/) under standard workflow and a non-redundant human protein sequence FASTA file from the UniProt/SwissProt database (June 29, 2011) modified to contain Bovine Serum Albumin (Swiss-Prot accession number P02769) and trypsin sequences. Search parameters were set to allow for two missed cleavage sites, variable modification of Methionine oxidation, protein N-terminal acetylation and phosphorylation of STY, one fixed modification of cysteine carbamidomethylation using precursor ion tolerances of 20 ppm for first search and 6 ppm for a second search. The ms/ms peaks were de-isotoped and searched using a 20 ppm mass tolerance. A stringent 1% false discovery rate threshold was used to filter candidate peptide, protein and phosphosite identifications.

Data analysis

Phosphopeptide motifs were extracted from http://motif-x.med.harvard.edu specifying a minimum of at least 20 occurrences, a strict p-value cutoff of <10-6 using the IPI Human proteome as a background. A biological assessment of the CD34+ HSPC phosphoproteome was evaluated using the Panther server (http://www.pantherdb.org/).

Individual phosphopeptide fractions datasets were collated and analyzed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) [19,20] to uncover biological processes, pathways, and transcription factors that are over or under expressed amongst the cognate proteins corresponding to the CD34+ HSPC phosphopeptides (as compared to T cells). using a signal to noise metric and gene sets downloaded from http://download.baderlab.org/EM_Genesets/ (April 16, 2012 release) [21]. GSEA results were subsequently visualized graphically using Enrichment Map, a cytotscape plugin [21].

Results

Phosphoproteome profiling

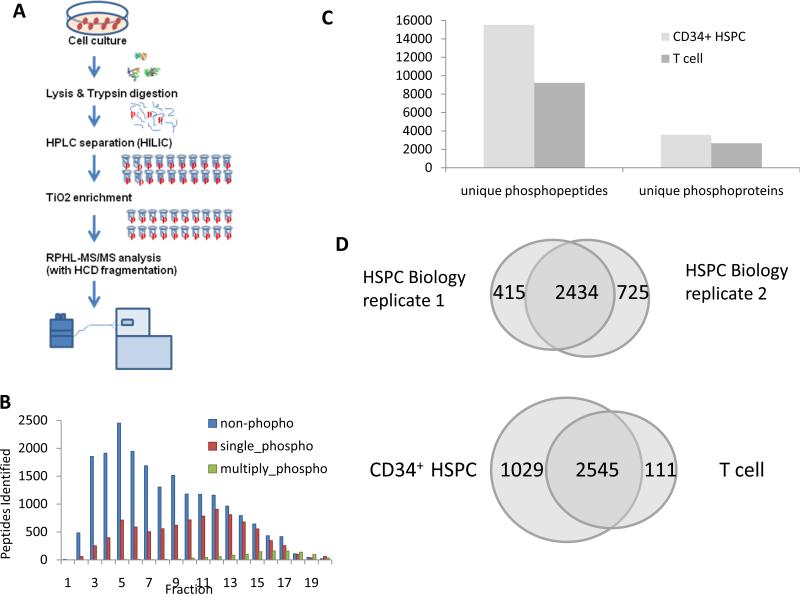

After generating soluble cell extracts, tryptic digests of CD34+ HSPC and CD3+ T cell derived polypeptides were separated each into 20 fractions using HILIC followed by TiO2-based phosphopeptide enrichment. In order to being enriched efficiently in the downstream process, the phosphopeptides need to be distributed more evenly across the fractions. Thus, the HPLC gradient was optimized to separate the phosphopeptide pools across the 20 fractions (Fig. 1B). Even though non-specific binding from nonphosphorylated peptides was evident across all the fractions, significantly more phosphopeptides (15533 unique instances) were enriched in this study compared to only 347 phosphopeptides in 229 phosphoproteins reported in previous study for CD34+ HSPC that performed phosphopeptide enrichment without front-end HILIC separation[8] (Fig. 1B). Due to the hydrophilicity of the column, however phosphopeptides with more than one phosphosite (i.e. multiple phosphorylations) tended to elute later in the gradient, whereas using SCX, due to poor retention, multiply phosphorylated peptides are often rarely retained or detected [12].

Figure 1. Global phosphoproteomic profiling of enriched human CD34+ HSPC and CD3+ T cell.

(A): The phosphopeptide separation and detection strategy used in this study combines HILIC and TiO2 enrichment as part of a 2D LC-MS/MS method. (B): Distribution plot showing the number of putative mono-site and multi- site containing phosphopeptides, and unmodified peptides, identified in the 20 fractions processed for CD34+ HSPC. (C): Comparison of the total number of unique phosphopeptides and phosphoproteins identified in CD34+ HSPC and CD3+ T cells. (D): Venn diagrams summarizing the overlap in phosphoprotein coverage obtained in two biological replicate analyses of CD34+ HSPC, as well as between CD34+ HSPC (with the proteins only found twice in two biological replicate) and T cells.

A total of 1804 peptides bearing multiple phosphorylation sites were detected in the CD34+ HSPC sample from this fractionation experiment. Using a stringent 1% FDR cutoff, 2434 distinct phosphoproteins were consistently identified in replicate analyses of two independent biological isolates of CD34+ HSPC (Fig. 1D; see Table S1 for details), establishing the good overall reproducibility of this HILIC-TiO2-RP-MS/MS system. Of these, 375 phosphoproteins consistently found in CD34+ HSPC were not detectable in a parallel HILIC-based phosphopeptide enrichment analysis of human CD3+ T cells (Fig. 1D). Hence, our phosphoprofiling strategy appears to have captured signaling features unique to HSPC.

Assessing biological function and the presence of phophorylation motifs

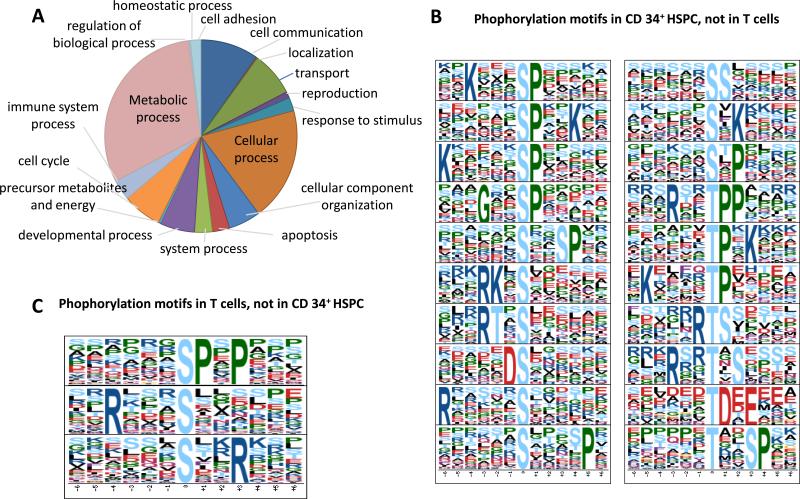

The range of biological functions represented in the CD34+ HSPC phosphoproteome were assessed using the Panther webtool (http://www.pantherdb.org/). As summarized in Figure 2A, the phosphoproteins mapped to 17 diverse biological processes.

Figure 2. Representative biological functions and phosphorylation motifs detected.

(A): Summary of the diverse functional annotations associated with the CD34+ HSPC phosphoproteome. (B). Phosphorylation motifs enriched in CD34+ HSPC, but not in T cell. (C). Phosphorylation motifs enriched in T cells, but not in CD34+ HSPC.

To assess the potential for differential kinase activation, we next evaluated the presence of phosphorylation motifs in both the CD34+ HSPC and CD3+ T cell phosphopeptidomes (Table S2, S3). For this enrichment analysis, the presence of 20 and 100 occurrences were chosen as thresholds for phosphothreonine and phosphoserine-containing sequences (so biased because of the relative low abundance of threonine phosphorylation in the overall phosphoproteome). In total, 34 motifs were found in common between the two cell lines (Table S2 and S3), whereas 20 motifs were preferentially detected in the CD34+ HSPC (listed in Fig. 2B) and another 3 motifs only in CD3+ T cells (listed in Fig. 2C). Almost half the motifs found in CD34+ HSPC reflect substrates of proline-directed kinases (...s/tP... concensus, where “s” represents phosphorylated Serine and “.” represents any amino acid). In both CD34+ HSPC and CD3+ T cells, the number of basophilic motifs (positively charged with K/R residues) was much more pronounced than acidophilic motifs (negatively charged with D/E residues), which might be unique for the blood cells since we did not find a a similar bias in analyses of other human cell types like HEK 293 cell line. While subject to more analyses, the CD34+ HSPC exhibited significantly more unique motifs compared to the CD3+ T cells, such as those consisting of ‘K...sP....’, ‘G..sP....’ and ‘...tP.K....’. The latter motif encompasses the known recognition sequences of the cell division CDK1-cyclin B kinase complex, a key driver of mitosis [22], consistent with the active proliferation of the HSPC population during expansion in vitro prior to sample processing.

Pathways and transcription factor binding sites

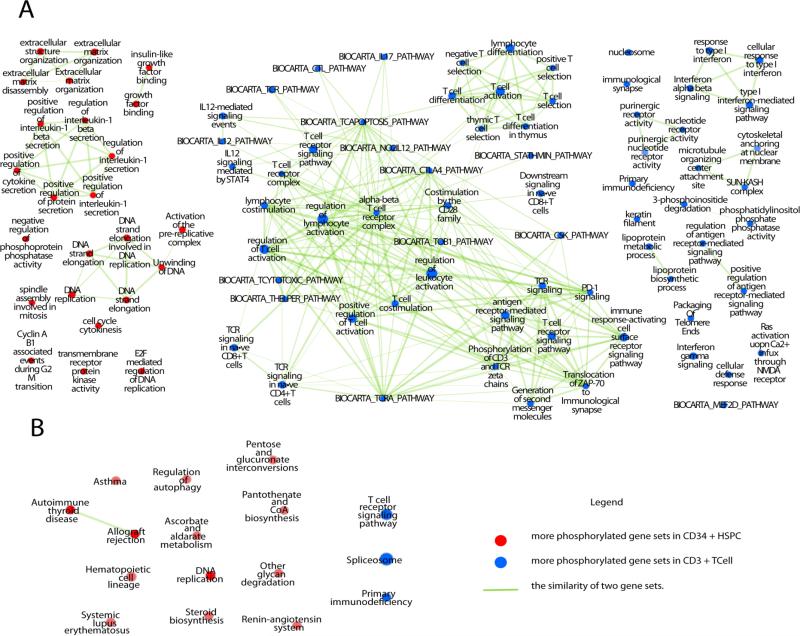

The global pattern of protein phosphorylation in the CD34+ HSPC and the downstream matured CD3+ T cell subpopulations were next analyzed to look for differential pathway and functional (biological process) activation using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). Using stringent cutoffs (p-value < 0.01, FDR < 0.1) and multiple-testing corrected tests, 24 gene sets were deemed significantly up-regulated in CD34+ HSPC phosphoproteome whereas 69 were down-regulated. For ease of analysis, the results were combined graphically and visualized using an Enrichment Map (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Enrichment maps of the CD34+ HSPC versus T cell phosphoproteomes.

Networks summarize the phosphoproteome enrichment results obtained by GSEA using gene sets (nodes) compiled from literature annotated functional categories and curated signalling pathways. Edges represent shared genes, with line width correlated with the similarity of two gene sets. Red nodes represent gene sets whose protein members are more extensively phosphorylated in CD34+ HSPC, while blue nodes represent gene sets whose members are enriched in T cells (or conversely, are less phosphorylated in CD34+ cells). Node size is correlated with the number of genes per set. (A): Enrichment map using gene sets for all relevant existing publicly accessible functional annotations. (B): Enrichment map using only gene sets extracted from the KEGG pathway database.

Cytokines are known to play an important role in regulating hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Consistent with this, 10 different cytokine-related gene sets were found to elevated in the CD34+ HSPC phosphoproteome. Most of these are known to be related to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell development. For example, insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF-binding proteins support ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)[23,24] . Cytokine-mediated receptor kinase activation, such as angiopoietin-1 receptor (TIE2)[25], c-Kit[26] and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt-3)[26], have been shown to transduce signals crucial for HSC development. In addition, intercellular feedback signals mediated by secreted proteins from HSC-derived differentiated progeny control HSC self-renewal versus differentiation[27,28]. Interleukin 1 (IL-1) and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), which were identified in the CD34+ HSPC enriched gene sets, are known paracrine signals to stimulate or inhibit HSPC expansion, respectively[29,30]. Moreover, 8 gene sets associated with DNA replication/cell-cycle progression were differentially up-regulated in HSPCs compared to CD3+ T cells, consistent with the greater proliferative potential of the primitive stem and progenitor cell population. Our analysis also pointed to the role of extracellular matrix (ECM) in controlling HSPCs, which is expected as HSC cell fate decision is tightly regulated by its microenvironment (niche) in bone marrow through cell-matrix interactions[31].

Conversely, for CD3+ Tcells, we detected enrichment for 49 gene sets associated with T cell receptor (TCR) signaling, which plays a pivotal role in regulating T cell survival, proliferation and differentiation, as well as cytokine production [32]. These include phosphorylation of the TCR/CD3 complex and its associated zeta chain, recruitment of ZAP-70 (a Syk family tyrosine kinase) to the zeta chain following receptor activation, activation of the downstream signaling cascades (e.g. PI3K/AKT, MAPK), hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol phosphate and the consequent generation of second messengers (e.g. diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol trisphosphate (IP3)), Ca2+ influx and production of IL-17 (which mediates the immune response against bacterial and fungal infection). Co-stimulatory signals mediated by other receptors expressed by T cells are also important in shaping T cell activation in immune reactions. Among them, CD4, CD8, CD28, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor [33], purinergic receptor [34], and receptors for IL-12, integrins [35], interferons (α, β, γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, were enriched in our analysis. In addition, 5 gene sets were related to the immunological synapse, that is, the cell-cell interaction interface between antigen-presenting cells and T cells which has a fundamental role in governing T cell activation[36]. Also consistent with previous studies[37,38], we detected 3 gene sets associated with histone modifications and the resulting changes in chromatin accessibility preferentially in T cells rather than in HSPC, which may indicate more profound epigenetic remodelling during cell differentiation and maturation. Unexpectedly, however, lipoprotein biosynthesis and metabolism were likewise identified in our analysis of T cells, although the biological significance of this finding warrants further investigation.

Signaling pathway regulation is especially important for hematopoietic cell fate decisions [7]. Hence, we applied the gene sets enrichment method to annotated KEGG pathways, and, using relatively more lax score cutoff s (p-value < 0.05, FDR < 0.24), found 13 pathways were up-regulated and 2 were down-regulated in the CD34+ HSPC compared to CD3+ T cells (Table S5, Fig. 3B). Here, a few additional gene set groups appeared in this approach besides cytokines, ECM and DNA replication factors. These include 6 gene sets related with autophagy and cell metabolism, which are known to regulate HSPC[39]. The small peptide Angiotensin-(1-7) was found to stimulate HSPC both vivo and vitro[40]. Of potential clinical relevance, 4 autoimmune system related disease gene sets were enriched, which are known to have blood cell specific properties.

Finally, to examine the downstream regulatory effects of signaling cascades, we evaluated gene sets constructed from groups of genes that share the same transcription factor binding site (TFBS) as defined in the TRANSFAC database (http://www.gene-regulation.com) using GSEA. From this, we found one gene set was up-regulated and 6 down-regulated in CD34+ HSPC (Table S6). The sole up-regulated transcription factor, GATA, is known to be important for HSC quiescence, activation and differentiation[41].

Discussion

It has been more than 50 years since bone marrow transplantation proved the existence of hematopoietic stem cells capable of self-replicating and generating progeny that can differentiate into all blood cell lineages. However, our understanding of the complexity of the signaling events controlling these cell fate decisions is only just now emerging. The past three decades of research on mammalian HSPCs has resulted in their prospective isolation and the identification of individual gene products and cognate signaling pathways that affect stem cell growth and differentiation [7]. Yet, methods to control stem cell fate - true self-replication and direct lineage commitment - remain elusive. This reflects a lack of knowledge of key time-resolved signaling events that drive lineage formation or which restrict development potential in blood progenitor populations.

In response to an external stimulus, such as binding of ligand to receptor, highly specific protein-protein interactions and protein modifications are initiated within developing hematopoietic cells. The reversible action of protein kinases, phosphatases and phosphopeptide binding domains (PBDs) are often essential for translocating signals from upstream signaling molecules to downstream effectors to initiate developmental cascades. The human genome encodes for ~500 putative protein kinases and a third of that for protein phosphatases [42], and defective expression of certain kinases and phosphatases and even mutations in PBDs is causally associated with blood disorders and cancers like chronic myelomonocystic and chronic myelogenous leukemias, to name a few [43] . Anecdotal evidence suggests that at least a third of all proteins present in a eukaryotic cells are likely phosphorylated at any given time [44]. Phosphorylation impacts blood protein function by influencing the physical associations between signaling proteins, leading to the formation of both transient and stable multiprotein complexes that perform distinct biological activities. Therefore, it is evident that protein phosphorylation is very important for the developmental biology of HSPC, regulating key cellular processes critical to normal blood cell physiology such as gene expression, cytoskeletal rearrangements, cell cycle progression, DNA repair and apoptosis [45].

Rapid growth of the mass spectrometry-based phosphopeptide separation and detection methods has provided the opportunity to systematically and globally analyze phosphoproteomes to infer kinase-substrate relationships. However, until very recently, the study of phosphoproteins in the biologically important CD34+ HSPC has been very limited, in large part due to the difficulty of detection and separation of low abundance phosphoproteins. For example, only 347 phosphopeptides in 229 phosphoproteins were identified in a recent study [8]. In this current study, HILIC based two dimensional HPLC separation coupled with TiO2 enrichment was used to enhance detection coverage of lower abundance phosphorylated proteins and peptides before high resolution precursor and fragment mass spectrometry. As a result, a large number of phosphorylation sites, most previously unreported, were detected in CD34+ HSPC with high confidence. Although 2-fold more putative phosphopeptides were tentatively identified in pilot analyses using CAD (data not shown)[12], we opted for HCD fragmentation in this current study due to the more reliable identifications it offers and for the potential ease of transfer of the acquired spectral information to an SRM style assay for validation using a QQQ instrument in follow up quantification studies.

In order to better understand the kinase recognition sequences and kinase-substrates relationships, over-represented sequence motifs present among all the candidate phosphopeptides were extracted. We found that CD34+ HSPC have markedly different patterns compared with CD3+ T cells. Moreover, gene enrichment analysis revealed differential pathways and biological processes impacted by phosphorylation in CD34+ HSPC, ranging from factors controlling blood cells regulation/activation/diffenrtiation, to cytokine regulators of the immune system, to factors impinging on cell growth and proliferation. Many of the gene sets detected encompass factors already known to be involved with HSPC fate decisions among quiescence, activation and differentiation. Further profiling studies aimed at dissecting the phosphoproteomes of additional progenitor subpopulations may help resolve the exact roles of the signaling events in hematopoietic cell specification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was generously supported by grants from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (HSF), Pew Biomedical Scholar Award (PJP), NIH/NHLBI U01 HL099993 (PJP) and NIDDK/NIH P30 DK56465 (PJP).

References

- 1.Orkin SH. Diversification of haematopoietic stem cells to specific lineages. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2000;1:57–64. doi: 10.1038/35049577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–11. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt RK, Loh Y, Pearce W, Beohar N, Barr WG, Craig R, Wen Y, Rapp JA, Kessler J. Clinical applications of blood-derived and marrow-derived stem cells for nonmalignant diseases. JAMA. 2008;299:925–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim YC, Wu Q, Chen J, Xuan Z, Jung Y-C, Zhang MQ, Rowley JD, Wang SM. The transcriptome of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem-progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:8278–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu F, Lu J, Fan H-H, Wang Z-Q, Cui S-J, Zhang G-A, Chi M, Zhang X, Yang P-Y, Chen Z, Han Z-G. Insights into human CD34+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells through a systematically proteomic survey coupled with transcriptome. Proteomics. 2006;6:2673–92. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao W, Wang M, Voss ED, Cocklin RR, Smith JA, Cooper SH, Broxmeyer HE. Comparative proteomic analysis of human CD34+ stem/progenitor cells and mature CD15+ myeloid cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22:1003–14. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-6-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SM, Zhang MQ. Transcriptome study for early hematopoiesis--achievement, challenge and new opportunity. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010;223:549–52. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponnikorn S, Panichakul T, Sresanga K, Wongborisuth C, Roytrakul S, Hongeng S, Tungpradabkul S. Phosphoproteomic analysis of apoptotic hematopoietic stem cells from hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia. J Transl Med. 2011;9:96. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han G, Ye M, Zou H. Development of phosphopeptide enrichment techniques for phosphoproteome analysis. Analyst. 2008;133:1128–38. doi: 10.1039/b806775a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song C, Ye M, Han G, Jiang X, Wang F, Yu Z, Chen R, Zou H. Reversed-Phase-Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography Approach with High Orthogonality for Multidimensional Separation of Phosphopeptides. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:53–6. doi: 10.1021/ac9023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beausoleil SA, Jedrychowski M, Schwartz D, Elias JE, Villén J, Li J, Cohn MA, Cantley LC, Gygi SP. Large-scale characterization of HeLa cell nuclear phosphoproteins. PNAS. 2004;101:12130–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jedrychowski MP, Huttlin EL, Haas W, Sowa ME, Rad R, Gygi SP. Evaluation of HCD- and CID-type fragmentation within their respective detection platforms for murine phosphoproteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M111.009910. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boersema PJ, Mohammed S, Heck AJR. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) in proteomics. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:151–9. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-1865-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNulty DE, Annan RS. Hydrophilic interaction chromatography reduces the complexity of the phosphoproteome and improves global phosphopeptide isolation and detection. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:971–80. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700543-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilar M, Olivova P, Daly AE, Gebler JC. Orthogonality of separation in two-dimensional liquid chromatography. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:6426–34. doi: 10.1021/ac050923i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swaney DL, McAlister GC, Coon JJ. Decision tree-driven tandem mass spectrometry for shotgun proteomics. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:959–64. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagaraj N, D'Souza RCJ, Cox J, Olsen JV, Mann M. Feasibility of large-scale phosphoproteomics with higher energy collisional dissociation fragmentation. J. Proteome Res. 2010;9:6786–94. doi: 10.1021/pr100637q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen JV, Macek B, Lange O, Makarov A, Horning S, Mann M. Higher-energy C-trap dissociation for peptide modification analysis. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:709–12. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. PNAS. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson K-F, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstråle M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:267–73. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merico D, Isserlin R, Stueker O, Emili A, Bader GD. Enrichment map: a network-based method for gene-set enrichment visualization and interpretation. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes JK, Solomon MJ. A Predictive Scale for Evaluating Cyclin-dependent Kinase Substrates A COMPARISON OF p34cdc2 AND p33cdk2. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:25240–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang CC, Kaba M, Iizuka S, Huynh H, Lodish HF. Angiopoietin-like 5 and IGFBP2 stimulate ex vivo expansion of human cord blood hematopoietic stem cells as assayed by NOD/SCID transplantation. Blood. 2008;111:3415–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang CC, Lodish HF. Insulin-like growth factor 2 expressed in a novel fetal liver cell population is a growth factor for hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2004;103:2513–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang CC, Kaba M, Ge G, Xie K, Tong W, Hug C, Lodish HF. Angiopoietin-like proteins stimulate ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2006;12:240–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kent D, Copley M, Benz C, Dykstra B, Bowie M, Eaves C. Regulation of hematopoietic stem cells by the steel factor/KIT signaling pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:1926–30. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Csaszar E, Kirouac DC, Yu M, Wang W, Qiao W, Cooke MP, Boitano AE, Ito C, Zandstra PW. Rapid Expansion of Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells by Automated Control of Inhibitory Feedback Signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:218–29. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirouac DC, Ito C, Csaszar E, Roch A, Yu M, Sykes EA, Bader GD, Zandstra PW. Dynamic interaction networks in a hierarchically organized tissue. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:417. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.W Brugger WM. Ex vivo expansion of enriched peripheral blood CD34 progenitor cells by stem cell factor, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta), IL-6, IL-3, interferon-gamma, and erythropoietin. Blood. 1993;81:2579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsson J, Karlsson S. The role of Smad signaling in hematopoiesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:5676–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth Factors, Matrices, and Forces Combine and Control Stem Cells. Science. 2009;324:1673–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torgersen KM, Aandahl EM, Taskén K. Molecular architecture of signal complexes regulating immune cell function. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2008:327–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72843-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miglio G, Varsaldi F, Lombardi G. Human T lymphocytes express N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors functionally active in controlling T cell activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:1875–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schenk U, Frascoli M, Proietti M, Geffers R, Traggiai E, Buer J, Ricordi C, Westendorf AM, Grassi F. ATP inhibits the generation and function of regulatory T cells through the activation of purinergic P2X receptors. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burbach BJ, Medeiros RB, Mueller KL, Shimizu Y. T-cell receptor signaling to integrins. Immunol. Rev. 2007;218:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis DM, Dustin ML. What is the importance of the immunological synapse? Trends Immunol. 2004;25:323–7. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutcliffe EL, Parish IA, He YQ, Juelich T, Tierney ML, Rangasamy D, Milburn PJ, Parish CR, Tremethick DJ, Rao S. Dynamic histone variant exchange accompanies gene induction in T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:1972–86. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01590-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei G, Wei L, Zhu J, Zang C, Hu-Li J, Yao Z, Cui K, Kanno Y, Roh T-Y, Watford WT, Schones DE, Peng W, Sun H-W, Paul WE, O'Shea JJ, Zhao K. Global mapping of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 reveals specificity and plasticity in lineage fate determination of differentiating CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:155–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerji V, Gibson SB. Targeting metabolism and autophagy in the context of haematologic malignancies. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:595976. doi: 10.1155/2012/595976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heringer-Walther S, Eckert K, Schumacher S-M, Uharek L, Wulf-Goldenberg A, Gembardt F, Fichtner I, Schultheiss H-P, Rodgers K, Walther T. Angiotensin-(1–7) stimulates hematopoietic progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo. Haematologica. 2009;94:857–60. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ku C-J, Hosoya T, Maillard I, Engel JD. GATA-3 regulates hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and cell-cycle entry. Blood. 2012;119:2242–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The Protein Kinase Complement of the Human Genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–34. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deininger MWN, Goldman JM, Melo JV. The molecular biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2000;96:3343–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann M, Ong S-E, Grønborg M, Steen H, Jensen ON, Pandey A. Analysis of protein phosphorylation using mass spectrometry: deciphering the phosphoproteome. Trends in Biotechnology. 2002;20:261–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01944-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blank U, Karlsson G, Karlsson S. Signaling pathways governing stem-cell fate. Blood. 2008;111:492–503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-075168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.