Summary

Motor neurone disease (MND), the commonest clinical presentation of which is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), is regarded as the most devastating of adult-onset neurodegenerative disorders. The last decade has seen major improvements in patient care, but also rapid scientific advances, so that rational therapies based on key pathogenic mechanisms now seem plausible. ALS is strikingly heterogeneous in both its presentation, with an average one-year delay from first symptoms to diagnosis, and subsequent rate of clinical progression. Although half of patients succumb within 3–4 years of symptom onset, typically through respiratory failure, a significant minority survives into a second decade. Although an apparently sporadic disorder for most patients, without clear environmental triggers, recent genetic studies have identified disease-causing mutations in genes in several seemingly disparate functional pathways, so that motor neuron degeneration may need to be understood as a common final pathway with a number of upstream causes. This apparent aetiological and clinical heterogeneity suggests that therapeutic studies should include detailed biomarker profiling, and consider genetic as well as clinical stratification. The most common mutation, accounting for 10% of all Western hemisphere ALS, is a hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9orf72. This and several other genes implicate altered RNA processing and protein degradation pathways in the core of ALS pathogenesis. A major gap remains in understanding how such fundamental processes appear to function without obvious deficit in the decades prior to symptom emergence, and the study of pre-symptomatic gene carriers is an important new initiative.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia, neurodegeneration, anterior horn cell, RNA, TDP-43, autophagy, protein aggregation

Introduction

Motor neurone disease (MND) is an adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder characterised by loss of upper motor neurons (UMNs, including the Betz cells of the motor cortex), and lower motor neuron (LMNs, anterior horn cells of the spinal cord and brainstem nuclei) (Figure 2a).1 The term MND is largely synonymous with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), reflecting the observation that most patients demonstrate combined LMN-related loss of muscle as a result of denervation (amyotrophy), and UMN degeneration of the lateral corticospinal tract and its cortical origins manifesting as gliosis, or hardening (sclerosis). Despite numerous therapeutic trials, there is no reversible treatment for what is typically a catastrophic collapse of a previously apparently normally functioning motor system.

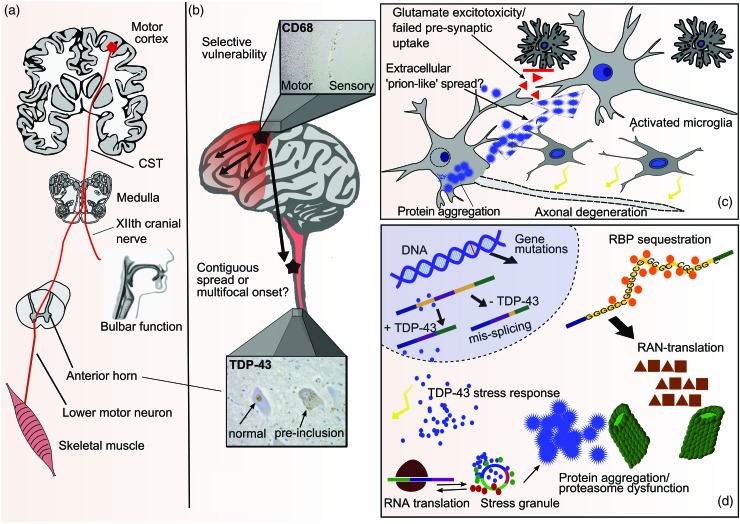

Figure 2.

Pathogenic overview of ALS from the systems to tissue to neuronal to molecular level. (a) ALS affects motor neurons in the motor cortex (UMN) and anterior horn of the spinal cord (LMN) and corticospinal tract (CST). Bulbar dysfunction frequently arises as a combination of corticobulbar tract involvement and brainstem LMN loss. (b) The disease affects predominantly the anterior part of the brain, sparing regions such as the sensory cortex (inset: CD-68 stain of a section covering parts of the primary motor cortex ‘M’ and primary sensory cortex ‘S’). Spread of disease may occur along contiguous anatomical regions or along functional connections. Multifocal onset is a possibility (lower inset: TDP-43 stain of spinal motor neurons showing some neurons with normal nuclear TDP-43, and cells with pathological cytoplasmic inclusions). (c) Protein aggregation, predominantly of TDP-43, is observed in affected motor neurons. Spread of prion-like protein aggregates from cell to cell is hypothetical. Glutamate excitotoxicity, in part mediated by failure of synaptic uptake of glutamate by astrocytes, is another potential mechanism of cell to cell spread. Activated microglia with pro-inflammatory properties may play a role in disease progression. (d) TDP-43 is thought to leave the nucleus as part of a physiological stress response. Stress granules transiently stall translation of specific mRNAs, but release them again to translating polysomes after resolution of the stress. Due to its prion-like domain, TDP-43 in stress granules may be an initial step to pathological TDP-43 aggregates which are cleared by the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy. Loss of nuclear TDP-43 may then lead to aberrant splicing of pre-mRNAs. Other RNA-binding proteins (RBP) may be trapped by ‘toxic’ RNA species, for example the hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9orf72. This is also translated into aggregating dipeptide repeats that need to be cleared by the protein degradation machinery.

It is no longer tenable to think of ALS as a disease restricted to the motor system. Extra-motor cerebral pathology, even if not always clinically obvious, is routinely observed on histopathological examination, with a predilection for the prefrontal, frontal and temporal cortices. This is associated with variable dysexecutive impairment and behavioural disturbance, and in up to 15% there is overt frontotemporal dementia (FTD). There is now a wealth of clinical and neuropathological evidence to support the notion of ALS and FTD as extremes of a spectrum2 (Figure 1).

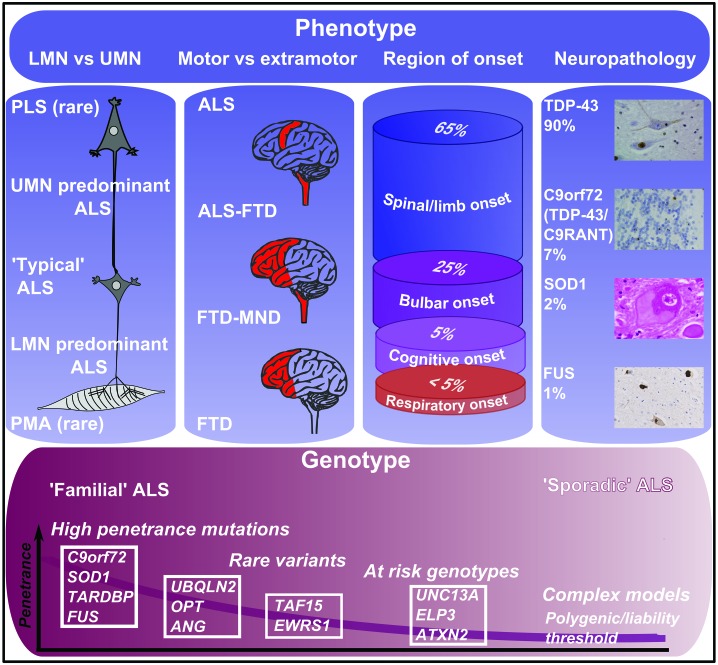

Figure 1.

Classification and nomenclature of MND. Note: MND can be classified according to clinical, neuropathological and genetic features. Importantly, a specific genetic or neuropathological category does not predict a completely distinct clinical phenotype. LMN, lower motor neurone; UMN, upper motor neurone; PLS, primary lateral sclerosis; PMA, progressive muscular atrophy.

Clinical features and diagnosis

The clinical hallmark of ALS is progressive motor weakness without sensory disturbance. Characteristically, loss of motor function is due to a combination of UMN and LMN involvement and, with signs of both demonstrable on examination, there are few credible mimic disorders.3 Rare ‘pure’ LMN or UMN cases, typically also more slowly progressive, present the greatest challenge diagnostically, although it is exceptional for a reversible disease to be missed in this context. Considerable distress arises when patients are denied appropriate support because of diagnostic procrastination.

Focality of symptom onset is a striking feature of ALS. Patients initially develop a weak limb (∼60%) or bulbar dysfunction manifesting as dysarthria (∼30%). Presentation with FTD or respiratory weakness (both ∼5%) is also seen. Characteristic regionally isolated variants of ALS may be delineated, including ‘flail arm’ or ‘man-in-a-barrel’ syndrome involving bilateral proximal and typically LMN-predominant arm weakness, and the flail leg or ‘pseudopolyneuritic’ syndrome, both typically much slower in progression. Although bulbar-onset ALS is frequently associated with more rapid progression of symptoms, a subgroup, typically elderly women, may develop rapid corticobulbar involvement (UMN-predominant, with severe emotionality) that remains isolated for many months, occasionally years, before the limbs become weak. Bulbar-onset patients are very frequently mis-referred to TIA or ENT clinics, and unnecessary spinal surgery can result from over-interpretation of incidental spondylotic disease in those with limb weakness.

Weakness in ALS progresses to affect other body parts in a contiguous manner. Cognitive impairment, if it occurs, is typically seen early in the disease course, often involves behavioural changes, and is generally associated with more rapidly progressive motor weakness. A more subtle dysexecutive syndrome is found in up to 50% of patients, but does not obviously progress in severity at the same rate as motor weakness. Death in ALS is typically due to gradual ventilatory failure. Choking is exceptional as a mode of death, even in those with profound bulbar weakness, and patients should be specifically reassured about this.

ALS is a clinical diagnosis based on eliciting a history of progressive motor dysfunction such as weakness and loss of dexterity, and demonstrating a combination of UMN and LMN signs. UMN signs may sometimes be hard to elicit. Electromyography (EMG) may be helpful in demonstrating LMN denervation. The sensitivity of EMG, however, is only 60%, so that it should not be considered a diagnostic or mandatory investigation. In the research setting, the diagnostic process has been formalized by the use of the El Escorial criteria, linking diagnostic certainty with the number of body regions affected clinically or neurophysiologically,4 with categories of ‘possible’ and ‘probable’ ALS. The neurophysiological aspects of the El Escorial criteria have been refined in the Awaji criteria,5 which likely improves their sensitivity,6 although they remain overly restrictive in clinical practice. As well as reaching a firm diagnosis, the aim of clinical assessment is to estimate the individual patient’s disease trajectory to facilitate the timing of interventions such as gastrostomy or non-invasive ventilation. These milestones have formed the basis for efforts aimed at disease ‘staging’ that might have benefit in clinical trials.7

Epidemiology

ALS is considered to occur throughout the world, though knowledge is incomplete, especially in Africa, India and China, where systematic epidemiology has not yet been carried out.8 Hotspots for the ALS-Parkinsonism-Dementia complex, described in the Japanese Kii Peninsula and on the Pacific island of Guam, are exceptional, still poorly understood in terms of aetiology, and pathologically distinct. A UK population-based study found an ALS incidence of 2.6 per 100,000 population per year for women, and 3.9 per 100,000 for men, resulting in a lifetime risk of 1 in 472 and 1 in 350, respectively.9 ALS is extremely rare below the age of 30 years, though cases linked to genetic mutations in FUS are seen in teenagers, and have a typically aggressive course.10 The risk of ALS increases after the age of 40 years and peaks in the early seventies, before a decline in incidence occurs that is unexplained. A younger age at symptom onset is a positive prognostic marker. Despite a median survival of approximately 3–4 years from onset of symptoms in population-based studies, there is marked prognostic heterogeneity in ALS. No consistent environmental risk factor has been identified, but there is a strong impression among many clinicians that patients with ALS have higher-than-average levels of pre-morbid physical fitness and lower body mass index.11 A possible explanation for an association may lie in a genetic profile that predisposes to athleticism but is somehow more permissive to motor system degeneration in later life.

Genetics

A genetic contribution to ALS was long thought to be significant for only the 5% of cases with a family history consistent with Mendelian inheritance. Incomplete gene penetrance and small family size are only two of many factors that led to an under-appreciation of the inherited contribution to ALS. For nearly two decades, only one-fifth of ‘familial’ cases (2% of all ALS) were accounted for genetically, through mutations in the superoxide dismutase-1 gene (SOD1). Now three-quarters of cases with a family history of either ALS or FTD are explained as autosomal dominant single gene disorders. The single most frequent genetic cause is an intronic hexanucleotide repeat expansion in open reading frame 72 on chromosome 9 (C9orf72).12 Mutations in SOD1, TARDBP and FUS occur in <10% of cases in population-based studies, and mutations in other genes are even more uncommon (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genetics of ALS.

| Gene | Function/disease mechanism | Phenotype | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| C9orf72 | Protein function unknown RNA toxicity of hexanucleotide repeat expansion, abnormal protein translation and haploinsufficiency may be relevant | ALS, FTD, unusual phenotypes | >30% of FALS >5% of SALS |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase enzyme Likely gain of function; protein aggregation | ALS, PMA FTD rare | 20% of FALS 2–7% of SALS |

| TARDBP | RNA and DNA binding Protein aggregation, RNA dysfunction | ALS, rarely FTD | Up to 5% FALS Up to 2% SALS |

| FUS | RNA and DNA metabolism Protein aggregation, RNA dysfunction | ALS Juvenile ALS with basophilic inclusions FTD with FUS pathology uncommon, no FTD caused by FUS mutations | 1–5% of FALS <1% of SALS |

| Angiogenin (ANG) | RNA metabolism Ribosome biogenesis Stress response | ALS, ALS-FTD | <1% of all ALS |

| Ataxin-2 (ATXN2) | RNA metabolism and stress response Modifier of TDP-43 toxicity in vitro | Intermediate-length CAG repeat (polyQ) expansion predisposes to ALS >34 repeats cause SCA2 | <1% of SALS |

| Optineurin (OPT) | Protein degradation, autophagy | ALS, ALS-FTD | <1% of all ALS |

| Ubiquilin-2 (UBQLN2) | Ubiquitin-like protein, protein degradation | X-linked dominant ALS and ALS-FTD | <1% of all ALS |

| P62 (SQSTM1) | Protein degradation, autophagy | ALS, FTLD | <1% of all ALS |

| Valosin-containing protein (VCP) | Protein degradation, autophagy | ALS inclusion Body myopathy with early-onset Paget disease and FTD | <1% of all ALS |

| FIG4 | Phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase, endosomal vesicle trafficking, autophagy | ALS Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease 4J | Unknown |

Note: Selection of important genes shown to cause ALS. RNA metabolism and protein degradation are common themes. An up-to-date list of gene mutations can be found at http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk

C9orf72 expansions account for 40% of familial ALS cases and one-quarter of familial FTD cases, and may cause either ‘pure’ ALS or FTD in members of the same family. While the clinical phenotypes are largely indistinguishable from non-C9orf72 related ALS and FTD, there appears to be an over-representation of ALS with cognitive impairment. The pathological expansion leads to a reduction of C9orf72 mRNA levels, but the functional consequences of this are unknown, as is the function of the encoded protein. Gain of function-related to RNA toxicity is currently favoured as a pathogenic mechanism.13

It is possible that all cases of ALS are at least partially genetically determined even in the absence of a family history. Great hope was pinned on genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to help uncover the ‘missing heritability’, but with the exception of a strong association with a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the gene UNC13A, few other findings have been replicated.14 Identified SNPs themselves are not necessarily biologically relevant, but can act as markers of genetic variants with which they are in linkage disequilibrium. Loci identified in GWAS are likely to have low odds ratios, and their functional significance in terms of disease aetiology may be difficult to ascertain, despite a significant contribution to the genetic make-up of the at-risk population as a whole.

Importantly, it has become apparent that, in the Western hemisphere at least, nearly 10% of apparently sporadic ALS cases carry expansions in C9orf72.15 Testing for mutations in C9orf72 may be appropriate in patients with a family history of ALS or FTD, and in cases of apparently sporadic ALS with prominent cognitive impairment. Testing for SOD1, TARDBP and FUS mutations has a low chance of yielding a positive result whether or not there is a family history of ALS. Pre-symptomatic genetic testing of patients' relatives is not recommended on the basis of current knowledge, and should only be carried out after formal genetic counselling.

Pathology and pathogenesis

ALS has a distinctive neuropathological signature. Astrogliosis and a sometimes intense microglial reaction can accompany loss of motor neuron cell bodies in the motor cortex, brain stem and spinal cord. Remaining neurons and some glial cells contain hallmark cytoplasmic inclusions of the ubiquitinated protein TDP-43 (Figure 2b).16

TDP-43 is a DNA- and RNA-binding protein (encoded by the TARDBP gene) with various functions in transcription, pre-mRNA splicing and translation control. In addition to forming potentially toxic cytoplasmic inclusions, the protein is cleared from its normal nuclear location in affected cells, suggesting a nuclear loss of function may also contribute to pathogenesis (Figure 2d). The vast majority of ALS cases, as well as a large proportion of non-tau FTD cases, are now considered ‘TDP-43 proteinopathies’. Important exceptions are cases of SOD1 and FUS-related ALS, in which TDP-43 appears normal, with SOD1 and FUS abnormally aggregated and ubiquitinated instead.

While TDP-43 pathology is also found in C9orf72 expansion carriers, there is notably extensive TDP-43 negative pathology characterised by ubiquitinated inclusions containing aggregates of abnormally translated dipeptide repeats derived from the hexanucleotide repeat expansion.17 The mechanism by which this intronic region can produce peptide is thought to be due to a novel translational mechanism not requiring a start codon, called repeat-associated non-ATG-initiated (RAN) translation. These inclusions are most conspicuous in the cerebellum and hippocampus. Understanding the relationship between dipeptide repeat deposition, TDP-43 pathology and the clinical phenotype is a priority.

ALS model systems have been based on transgenic over-expressing SOD1 rodents for nearly two decades. This has generated a variety of candidate pathogenic mechanisms, including failure of axonal transport, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity,18 with growing concern at the lack of therapeutic translation. The discovery of TARDBP and FUS mutations, and the recognition that both are related RNA-binding proteins, has focused the search for upstream disease mechanisms on RNA metabolism. Several other ALS-related genes have roles in RNA metabolism, as do genes mutated in other, non-ALS motor neuron disorders, e.g. spinal muscular atrophy.19 A generic hypothesis is therefore that RNA metabolism at the level of mRNA splicing, transport or translation regulation, is altered. This could be mediated by loss of nuclear TDP-43 or FUS, or by cytosolic aggregation of these proteins. The presence of an abnormal hexanucleotide repeat in C9orf72 could lead to altered homeostasis of RNA-binding proteins. Loss of TDP-43 from mouse brain leads to altered mRNA splicing, as does over-expression of disease-causing TARDBP mutations.20

Another major theme in pathogenesis is abnormal protein aggregation. Intraneuronal inclusions are ubiquitinated, but also linked to autophagy via p62, a protein targeting ubiquitinated cargoes for clearance. Both the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy are vital for cellular survival, and it is possible that these systems are overwhelmed in ALS, either through an overload of aggregating protein or primary dysfunction of the protein degradation machinery. Several rare forms of ALS are caused by mutations in genes directly involved in protein degradation pathways. These include: UBQLN2, encoding the UPS component ubiquilin 2; SQSTM1, encoding p62; VCP, encoding the polyubiquitylated protein binding valosin containing protein; and others, including OPTN and FIG4.

Dysregulated RNA metabolism and abnormal protein aggregation are not mutually exclusive themes. Many RNA-binding proteins are exceptionally prone to aggregation as a consequence of carrying a prion-like domain. These domains are functionally important, facilitating transient aggregation to form protein-RNA granules. It has been hypothesised that abnormal protein inclusions in ALS may arise from physiologically occurring ‘stress granules’ that persist longer than needed because of mutations or chronic stress. These might then seed abnormal protein aggregation, possibly compounded by a failing clearance mechanism, such as defective autophagy. Sequestration of more RNA-binding proteins may then lead to abnormal RNA handling.

Whatever the precise mechanism of initial neuronal injury is, it appears to be accompanied by an immune reaction, most visible in the form of microglial activation. There is a balance of neuroprotective (M2-like) and cytotoxic (M1-like) sub-populations of microglial cells, and it is likely that the ratio between the two has an impact on disease progression. It is less clear whether there is a primary role for the immune system in pathogenesis, but an excess of autoimmune diseases prior to ALS supports shared genetic or environmental factors.21

Biomarkers

There is a need for biomarkers that might reduce diagnostic delay, or improve prognostic stratification and therapeutic response assessment.22 Trials currently rely on survival as the primary endpoint, or change in the slope of the revised ALS Functional Rating Score (ALSFRS-R), both of which lack sensitivity. CSF neurofilaments, TDP-43 and neuroinflammatory molecules may reflect aspects of disease pathogenesis and progression, but need validation in large cohorts. Neurophysiology offers quantitative LMN biomarker candidates, for example Motor Unit Number Estimation (MUNE) and electrical impedance myography.18 Cortical hyperexcitability, measured using transcranial magnetic stimulation, has promising specificity for ALS.23 While routine clinical MRI is frequently used to rule out structural lesions in the differential diagnosis of ALS, more advanced quantitative applications have emerged that are leading the way in defining a systems-level biomarker signature.24 Voxel and surface-based morphometry of the cortex, and diffusion tensor imaging measures of white matter tract integrity have shown promise across the range of phenotypes. Thinning of the primary motor cortex and loss of corticospinal tract and corpus callosum integrity are consistent findings. Functional MRI across the so-called resting-state networks reveals changes in functional connectivity that may be linked pathogenically to structural changes. While no single neuroimaging finding has currently permitted discrimination of disease state at the level of the individual, it is hoped that a combination of markers will prove effective.

Therapy

Disappointingly, the only drug to demonstrate survival benefit in human ALS is riluzole, thought to have a broadly anti-glutamatergic mode of action. Its effects are very modest, prolonging mean survival from 12 to 15 months in the clinical trial setting. Emerging therapeutic strategies include those aimed at improving muscle function, an example being anti-NOGO-A antibodies thought to encourage axonal growth, based on models of spinal cord trauma.

Of much higher impact on quality of life for patients has been the development of a multidisciplinary team approach within specialist clinics, led by ALS-focused neurologists with a specialist nurse, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, dietician and physiotherapy support, plus links to gastroenterology and respiratory teams.25 Key interventions to be considered are nutritional management, including timely gastrostomy to maintain quality of life in dysphagic patients. Non-invasive ventilation has a significant survival as well as important quality-of-life benefits. Invasive tracheostomy does not mitigate the inexorable loss of limb function or likelihood of cognitive impairment, so that patients rarely choose this. End of life in ALS is typically managed with the close support of palliative care services.

Future developments

New pathogenic insights are emerging from the recognition of cognition as the ‘third space’ in addition to the traditional UMN and LMN pathology in ALS. The recognition of ALS and FTD as spectrum disorders broadens the concept of selective vulnerability to encompass neuronal networks, rather than cell types.26 At the systems level, the notion that toxic prion-like proteins may help to propagate disease along contiguous regions is being actively considered. According to this theory, major ALS proteins including SOD1, TDP-43 and FUS start to seed foci of aggregation which can spread from cell to cell through permissive templating, either from neuron to neuron or via glial cells (Figure 2c).27 This theory is an attractive match to the clinical observation that disease appears to spread from a focal point of onset to a neighbouring area28 and the concept of ‘spread’ of disease is closely related to the conundrum of selective vulnerability in ALS. Why some sub-populations of motor neurons are notably resistant, including those supplying the extraocular muscles, remains opaque. Physiological differences between these types of motor neurons are well established, and differences in the transcriptome have begun to emerge, which may lead to a better understanding of neuronal susceptibility at the molecular level.29

It is becoming clear that ALS is a syndrome with a heterogeneous aetiology. The full genetic contribution to this may be elucidated within the next decade, utilising the power of new sequencing technologies. This should lead to the development of improved disease models. Even now, TDP-43, rather than SOD1-based rodent models may better reflect the majority of human ALS, but the challenge will be to model the broader effects of biological ageing in a feasible time frame. The technology of producing motor neuron-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells, in turn generated from patient fibroblasts, shows promise as a model system more relevant to disease than over-expressing cDNA constructs in cell lines.30 It might conceivably be used as a platform for high-throughput drug screening. Conversely, the potential for therapeutic use of stem cell-derived motor neurones seems less certain, given the target of replacing long and precisely targeted axonal outgrowths that were established in early development. This approach might have more potential by creating a neuroprotective microenvironment for degenerating cells.

In the presence of a pathogenic mutation, there is potential for gene therapy in ALS. The C9orf72 hexanucleotide expansion might theoretically be targeted by antisense oligonucleotides to prevent RNA toxicity, an approach already being pioneered in myotonic dystrophy. However, such highly individualised therapies would only be useful for a minority of patients, and so strategies will need to harness the increasing understanding of the complex molecular and physiological alterations downstream of the genetic defect, to provide treatments focused on common pathways. One example might be strategies to restore or boost cortical inhibitory interneuronal functions.31

It seems likely that pathological events occur years, if not decades prior to symptoms, and the study of pre-symptomatic individuals carrying high-risk ALS mutations offers unique potential to capture the very earliest changes and even begin to consider primary prevention.32 If the pace of molecular, cellular and systems-level neuroscientific discovery continues its exponential increase, then an emerging therapeutic era for ALS seems assured within a much shorter time frame than could have been envisaged a decade ago.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

DB is supported by an OHSRC/BRC/NOHF Fellowship Grant and MRT is supported by the Medical Research Council & Motor Neurone Disease Association UK Lady Edith Wolfson Senior Clinical Fellowship (MR/K01014X/1)

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Guarantor

MRT

Contributorship

DB drafted the manuscript. KT edited the manuscript. MRT conceived and edited the manuscript

Acknowledgements

None

Provenance

Invited contribution; peer-reviewed by Matthew Kiernan

References

- 1.Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2011; 377: 942–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phukan J, Elamin M, Bede P, et al. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012; 83: 102–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner MR, Talbot K. Mimics and chameleons in motor neurone disease. Pract Neurol 2013; 13: 153–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2000; 1: 293–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Carvalho M, Dengler R, Eisen A, et al. Electrodiagnostic criteria for diagnosis of ALS. Clin Neurophysiol 2008; 119: 497–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa J, Swash M, de Carvalho M. Awaji criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis:a systematic review. Arch Neurol 2012; 69: 1410–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roche JC, Rojas-Garcia R, Scott KM, et al. A proposed staging system for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 2012; 135: 847–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beghi E, Logroscino G, Chio A, et al. The epidemiology of ALS and the role of population-based registries. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1762: 1150–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso A, Logroscino G, Jick SS, Hernan MA. Incidence and lifetime risk of motor neuron disease in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Eur J Neurol 2009; 16: 745–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumer D, Hilton D, Paine SM, et al. Juvenile ALS with basophilic inclusions is a FUS proteinopathy with FUS mutations. Neurology 2010; 75: 611–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turner MR. Increased premorbid physical activity and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: born to run rather than run to death, or a seductive myth? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84: 947–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron 2011; 72: 245–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Blitterswijk M, DeJesus-Hernandez M, Rademakers R. How do C9ORF72 repeat expansions cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: can we learn from other noncoding repeat expansion disorders? Curr Opin Neurol 2012; 25: 689–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A. Clinical genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: what do we really know? Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7: 603–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majounie E, Renton AE, Mok K, et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 323–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 2006; 314: 130–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mori K, Weng SM, Arzberger T, et al. The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science 2013; 339: 1335–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner MR, Bowser R, Bruijn L, et al. Mechanisms, models and biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2013; 14: 19–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bäumer D, Ansorge O, Almeida M, Talbot K. The role of RNA processing in the pathogenesis of motor neuron degeneration. Expert Rev Mol Med 2010; 12: e21–e21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polymenidou M, Lagier-Tourenne C, Hutt KR, et al. Long pre-mRNA depletion and RNA missplicing contribute to neuronal vulnerability from loss of TDP-43. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14: 459–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner MR, Goldacre R, Ramagopalan S, Talbot K, Goldacre MJ. Autoimmune disease preceding amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: an epidemiologic study. Neurology 2013; 81: 1222–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner MR, Kiernan MC, Leigh PN, Talbot K. Biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 94–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vucic S, Cheah BC, Yiannikas C, Kiernan MC. Cortical excitability distinguishes ALS from mimic disorders. Clin Neurophysiol 2011; 122: 1860–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turner MR, Agosta F, Bede P, Govind V, Lule D, Verstraete E. Neuroimaging in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biomark Med 2012; 6: 319–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardiman O, van den Berg LH, Kiernan MC. Clinical diagnosis and management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2011; 7: 639–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisen A, Turner MR. Does variation in neurodegenerative disease susceptibility and phenotype reflect cerebral differences at the network level? Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2013 doi: 10.3109/21678421.2013.812660. Jul 24. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2013.812660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. The seeds of neurodegeneration: prion-like spreading in ALS. Cell 2011; 147: 498–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravits JM, La Spada AR. ALS motor phenotype heterogeneity, focality, and spread: deconstructing motor neuron degeneration. Neurology 2009; 73: 805–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brockington A, Ning K, Heath PR, et al. Unravelling the enigma of selective vulnerability in neurodegeneration: motor neurons resistant to degeneration in ALS show distinct gene expression characteristics and decreased susceptibility to excitotoxicity. Acta Neuropathol 2013; 125: 95–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bilican B, Serio A, Barmada SJ, et al. Mutant induced pluripotent stem cell lines recapitulate aspects of TDP-43 proteinopathies and reveal cell-specific vulnerability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 5803–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turner MR, Kiernan MC. Does interneuronal dysfunction contribute to neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2012; 13: 245–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benatar M, Wuu J. Presymptomatic studies in ALS: Rationale, challenges, and approach. Neurology 2012; 79: 1732–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]