Abstract

Liver diseases in pregnancy although rare but they can seriously affect mother and fetus. Signs and symptoms are often not specific and consist of jaundice, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Although any type of liver disease can develop during pregnancy or pregnancy may occur in a patient already having chronic liver disease. All liver diseases with pregnancy can lead to increased maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is difficult to identify features of liver disease in pregnant women because of physiological changes. Physiological changes of normal pregnancy can be confounding with that of sign and symptoms of liver diseases. Telangiectasia or spider angiomas, palmar erythema, increased alkaline phosphatase due to placental secretion, hypoalbuminemia due to hemodilution. These normal alterations mimic physiological changes in patients with decompensated chronic liver disease. Besides all these pathological changes however, blood flow to the liver remains constant and the liver usually remains impalpable during pregnancy. The diagnosis of liver disease in pregnancy is challenging and relies on laboratory investigations. The underlying disorder can have a significant effect on morbidity and mortality in both mother and fetus, and a diagnostic workup should be initiated promptly. If we see the spectrum of liver disease in pregnancy, in mild form there occur increase in liver enzymes to severe form, where liver failure affecting the entire system or maternal mortality and morbidity. It can not only complicate mother's life but also poses burden of life of fetus to growth restriction. Most of the times termination is only answer to save life of mother but sometimes early detection of diseases, preventive measures and available active treatment is helpful for both of the life. Extreme vigilance in recognizing physical and laboratory abnormalities in pregnancy is a prerequisite for an accurate diagnosis. This could lead to a timely intervention and successful outcome.

Keywords: Complications, delivery, hepatobiliary diseases, outcome, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

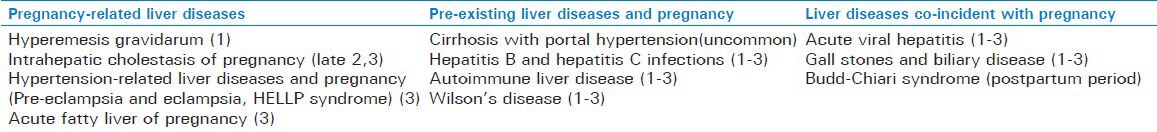

We reviewed the pubmed, Cochrane database with the key words like hepatobiliary diseases, liver disease, pregnancy, management, complications and outcome. Present review is the latest available information on diagnosis and managementon above related topics from 2000 to 2012. Liver disease during pregnancy is although rare, but it can complicate up to 3% of all pregnancies.[1] During a normal pregnancy in liver function test alkaline phosphatase activity increases due to added placental secretion. The aminotransferase concentrations (alanine and aspartate), bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT) and prothrombin time all remain normal throughout pregnancy. Their increase in pregnancy is always pathological, and should be further investigated. Liver diseases in pregnancy can be categorized according trimester of occurrence or for easy description. we classified the liver diseases during pregnancy in present review are as follows [Table 1].

Table 1.

Classification of liver diseases with pregnancy (Trimester vise occurrence)

Pregnancy-related liver diseases

Hyperemesis gravidarum

Hyperemesis gravidarumis defined as intractable nausea and vomiting during pregnancy that often leads to fluid and electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, ketonuria, catabolism. There may weight loss of 5% or greater and nutritional deficiency requiring hospital admission.[2] The incidence of HG varies from 0.3% to 2% of all live births.[3] HG often occurs between the 4th and 10th weeks of gestation and usually resolves by the 20th week. However, in approximately 10% patients, symptoms resolve only with delivery of the fetus. The etiology is multifactorial includes hormonal, immunologic, and genetic factors but remains a poorly understood condition. There is increase in human chorionic gonadotropin levels, stimulation of the thyroid gland, elevations of estrogen, decreases in prolactin levels, and over activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In immune mechanism, an increased level of tumor necrosis factor-alpha is involved.[4] Treatment is supportive with correction of dehydration and electrolyte disturbance, antiemetic therapy, thiamine and folate supplementation. The prevention and treatment of complications like Wernicke's encephalopathy, osmotic demyelination syndrome, thromboembolism, and good psychological support is essential. Patients should avoid triggers that aggravate nausea and eat small, frequent, low-fat meals. Antiemetic such as promethazine, metoclopramide, ondansetron and prochlorperazine may benefit selected patients and steroids have also been used.

In newer treatments, pyridoxine appears to be more effective in reducing the severity of nausea. The results from trials of P6 acupressure are equivocal.[5] Severe cases require thiamine and total parenteral nutrition. Aminotransferases values can rise up to 200U/L with mild jaundice.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy occurs in the late second or third trimester, also known as obstetric cholestasis. It has prevalence of about 1/1000 to 1/10,000 and are more common in South Asia, South America and Scandinavian countries. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is more common in women with multiparity, advanced maternal age and in women with history of cholestasis with oral contraceptive use. The prognosis is usually good. The etiology is multifactorial includes, genetic, hormonal and environmental factors. Pregnancy-associated increase in estrogen, progesterone and mutations in canalicular bile salt export pump(ABCB11) and multidrug resistant protein-3 (MDR3,ABCB4) gene lead to increased sensitivity to estrogen, which impairs sulfation and transportation of bile acids, decrease hepatocytes membrane permeability and bile acid uptake by the liver.[6] The high bile acid levels affect myometrial contractility and causes vasoconstriction ofchorionic veins in placenta, which leads to preterm deliveries, meconium staining of liquor, fetal bradycardia, distress and fetal loss associated with fasting serum bile acid levels >40 μmol/L. The fetal complications correlate with serum bile acid concentrations. The fetal risk is very low if levels remain below 40 μmol/L.

The classic maternal symptom is pruritus usually begins in the second or third trimester in palms and soles, may progress to rest of the body, it often worsens at night. Jaundice occurs in approximately 10-25% of patients and may appear within the first four weeks of pruritus.[7] The frequency of cholelithiasis and cholecystitisis are more in women with ICP. Other symptoms include fatigue, anorexia, epigastric pain, and steatorrhea due to fat malabsorption. Malabsorption may also lead to vitamin K deficiency leading to prolonged PT and postpartum haemorrhage. Also, as the normal fetal-to-maternal transfer of bile acids across the trophoblast is impaired, the excess bile acids with abnormal profiles accumulate and are toxic to the fetus.[8] The key diagnostic test is a fasting serum bile acid concentration of greater than 10 μmol/L. Abnormal laboratory findings include elevated aaminotransferase 2-10 folds and may exceed 1000U/L. Total bile acid levels up to 10 to 100 fold, with increased cholic acid and decrease chenodeoxycholic acid with markedly elevated cholic/chenodeoxycholic acid ratio. Bilirubin levels may be elevated but usually less than 6 mg/dL. Serum alkaline phosphatase levels may be elevated 7-10 times, but due to pregnancy, less helpful to follow. Histopathologic findings on liver biopsy include nondiagnostic centrilobular cholestasis without inflammation and bile plugs in hepatocytes and canaliculi.

The treatment of choice for ICP is synthetic bile acid ursodeoxycholic acids (UDCA), which relieves pruritus and improve liver test abnormalities.[9] UDCA increases expression of placental bile acid transporters and improves bile acid transfer. Other medications are cholestyramine, S-adenosyl-L-methionine and dexamethasone but UCDA is superior. Antihistamines are given to relieve pruritus and vitamin K and other fat-soluble vitamin supplementation, if fat malabsorption is suspected. ICP normally resolves after delivery but, in rare cases of familial forms, the condition can persist after delivery, leading to fibrosis and even cirrhosis.[10]

Hypertension-related liver diseases and pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia is a multisystem disorder complicatesabout 2-8% of all pregnancies.[11] It can involve the kidneys, CNS, hematological system, and liver. The etiology of this condition is unknown, but it seems that uteroplacental ischemia cause activation of endothelium. All of clinical feature of pre-eclampsia can be explained as maternal response to generalized endothelial dysfunctionleads to impairment of the hepatic endothelium contributing to onset of the HELLP syndrome. Disturbed endothelial control of vascular tone causes hypertension, increased permeability results in edema and proteinuria, and abnormal endothelial organs such as the brain, liver, kidney and placenta.[12] Clinical features include right upper abdominal pain, headache, nausea, and vomiting, visual disorders. Complications include maternal hypertensive crises, renal dysfunction, hepatic rupture or infarction, seizures, and increased perinatal morbidity and mortality. On the fetal the deleterious effect of hypertensive disorder are especially intrauterine growth retardation, oligohydramnios, or fetal death in utero.

Eclampsia is the major neurological complication of pre-eclampsia. Abnormal laboratory values include a 10 to 20, fold elevation in aminotransferases, elevations in alkaline phosphatase levels that exceed those normally observed in pregnancy, and bilirubin elevations of less than 5 mg/dl. Liver histology generally shows hepatic sinusoidal deposition of fibrin along with periportal hemorrhage, liver cell necrosis, and in severe cases, infarction.[13] Maternal and neonatal morbidity may include placental abruption, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction or maternal renal failure, pulmonary edema, or cerebrovascular accident.

The only effective treatment for pre-eclampsia is delivery of the fetus and placenta.[14] Magnesium sulfate is indicated in the treatment of eclamptic convulsions as well as for secondary prevention of eclampsia in severe pre-eclampsia.[15]

HELLP syndrome

The incidence among pregnant patients is 0.5-0.9%, and in presence of severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia the incidence is 10-20%. HELLP syndrome is characterized by three diagnostic lab criteria, hemolysis (H), elevated liver tests (EL), and low platelet count (LP).[16] Although HELLP is a severe form of pre-eclampsia having rest of the same symptoms. It can develop in women who might not have developed hypertension or proteinuria and diagnosis is confirmed by angiogenic markers including decreased placental growth factor, increased serum soluble endoglin, and increased soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (VEGF) receptor.[17]

Etiology: The HELLP syndrome is a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia associated with vascular endothelial injury, fibrin deposition in blood vessels, and platelet activation with platelet consumption, resulting in small to diffuse areas of hemorrhage and necrosis leading to large hematomas, capsular tears, and intraperitoneal bleeding.

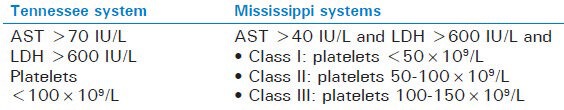

Clinical Features and Diagnosis: There are no diagnostic clinical features to distinguish HELLP from pre-eclampsia. Most patients present between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation, but about 25% in postpartum period. The diagnosis of HELLP must be quickly made because of maternal and fetal risk needed the necessity for immediate delivery. Occasionally, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) may be present. Aminotransferase elevation is from mild to 10-20 fold, and bilirubin is usually <5 mg/ dl. Computed tomography of the liver may show sub capsular hematomas, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, infarction or hepatic rupture. The PT or INR remains normal unless there is DIC or severe liver injury. A serum uric acid >7.8mg/dl is associated with increased maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.[18] Microscopic findings may be non-specific or similar to those of pre-eclampsia. Recognized classification systems of HELLP include the Tennessee and the Mississippi systems shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Recognized classification systems of HELLP include the tennessee and the mississippi systems

Management of HELLP

If possible shift the patient with HELLP to a tertiary referral center and a hepatic computed tomography obtained. The patient must be hospitalized for antepartum stabilization of hypertension, DIC, for seizure prophylaxis, and fetal monitoring. Delivery is the only definitive therapy. Prophylactic antibiotics and blood or blood products to correct hypervolemia, anemia, and coagulopathy are recommended. Maternal platelet count decreases immediately after delivery, then rises starting with day 3 postpartum, reaching>100,000/mm3 after day 6th of postpartum. If platelets do not increase after 96 hours from delivery, it indicates severe condition with possible development of multiple organ failure.[19] Corticosteroids use in HELLP syndrome does not show effect on clinical outcomes.[20]

Complications of the HELLP syndrome

Serious maternal complications are common like DIC, abruptio placentae, acute renal failure, eclampsia, pulmonary edema, acute respiratory distress syndrome, severe ascites, sub capsular hematoma, hepatic failure, and wound hematomas. In subsequent pregnancies there is high risk of pre-eclampsia, recurrent HELLP, prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, abruptio placentae and perinatal mortality.

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

It is a rare disorder of the third trimester affecting with an incidence of 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 15,000of pregnant women and inherited as autosomal recessive traits. It is most common in primiparous women older than 30 years and in women with multiple gestations carrying a male fetus. During pregnancy, levels of free fatty acids increase in maternal blood due to effect of hormone sensitive lipase and gestational insulin. These fatty acids transported into cell and oxidation of fatty acids by the mitochondria provides the energy necessary for the growth of fetus. Defect in genes G1528C and E474Q leads to deficiency of long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) enzyme. It is a component of an enzyme complex known as the mitochondrial trifunctional protein (MTP) required for transport and oxidation pathway of fatty acids.[21] During the last trimester due to increase metabolic demands of fetus, mother heterozygous for fatty acid oxidation disorder and with an affected fetus can develop Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) because of their inability to metabolize fatty acids for energy production and fetal growth. Fetal fatty acids accumulate and return to the mother's circulation and lead to hepatic fat deposition and impaired hepatic function in the mother. Typical symptoms are 1 to 2 weeks history of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and fatigue. Progression to moderate to severe hypoglycemia, coagulopathy, marked decreased of antithrombin III activity, encephalopathy and frank liver failure can rapidly ensue. Approximately 50% of patients will also have signs of pre-eclampsia. DIC is seen in about 80-100% of patients with AFLP as compare to 21% of patients with HELLP syndrome.[22]

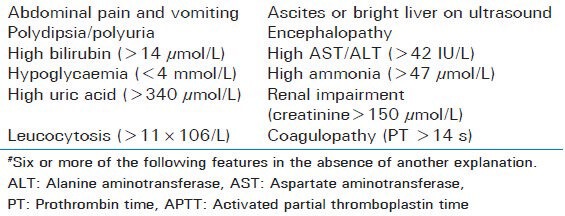

Laboratory findings include elevations in aminotransferase levels from mild to approaching 1000 IU/L, raised PT and bilirubin concentrations. In 98% of cases involve neutrophilic leukocytosis. As the disease progresses there may thrombocytopenia (with or without DIC) and hypoalbuminemia. Rising uric acid levels and impaired renal function may also be seen. Ultrasonography and computed tomography might be inconsistent. Therefore; the diagnosis of AFLP is usually made on clinical and laboratory findings. Most definitive test is liver biopsy but contraindicated in coagulopathy. Histopathology findings reveal swollen, pale hepatocytes in the central zones with microvesicular fatty infiltration as minute cytoplasmic vacuoles or diffuse cytoplasmic ballooning. The Swansea diagnostic criteria are an alternative to liver biopsy [Table 3].

Table 3.

Swansea diagnostic criteria for diagnosis of acute fatty liver of pregnancy#

Management of acute fatty liver of pregnancy

As with most pregnancy-associated liver diseases, the treatment of Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP) involves delivery of the fetus. In rare cases, patients will progress to fulminant hepatic failure requiring liver transplantation. Due to the development of more rapid diagnosis tools and early termination of pregnancy, maternal mortality rate due to this disease has decreased from 80-85% to 7-18% and the fetal mortality rate from 50% to 9-23%.[23] Homozygous Infant suffers from failure to thrive, hepatic failure, cardiomyopathy, neuropathy, myopathy, non-ketotic hypoglycaemia, and death. Thus mother and children born to mother with AFLP should be screened for defects in fatty acid oxidation. AFLP can occur in subsequent pregnancies in mothers and children (25%) in bothif women are carrying these mutations. Treatment of infant is the administration of medium-chain triglycerides.

Pre-existing liver diseases and pregnancy

Cirrhosis with portal hypertension

Etiology of cirrhosis in pregnancy is similar to non-pregnant state and commonly includes alcohol and viral hepatitis C and B. Pregnancy in cirrhotic women is rare due to hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction leading to disturbed estrogen and endocrine metabolism. Cirrhosis is not a contraindication for pregnancy, if cirrhosis is well-compensated and without features of portal hypertension. In cirrhotic pregnant women the rate of spontaneous abortion, prematurity, and perinatal death are increased. Non cirrhotic portal hypertension worsens during pregnancy because of increased blood volume and increased vascular resistance due to inferior vena cava compression by the gravid uterus. Non cirrhotic portal hypertension may leads to variceal hemorrhage, hepatic failure, encephalopathy, jaundice, splenic artery aneurysm and premature deliveries. The 20-25% of pregnant women with cirrhosis may have variceal bleeding, especially during the second trimester, when portal pressures peak, and during delivery because of straining to expel the fetus.[24]

Management

The treatment of variceal bleeding consists of both endoscopic and pharmacologic treatment. Patients with known esophageal varices should be considered for endoscopic therapy, shunt surgery, or even liver transplantation before pregnancy. All pregnant patients with cirrhosis should undergo endoscopic assessment of varices in the second trimester. Even if no varices found by endoscopy before pregnancy and if varices are large, then beta blocker therapy is indicated. Propranolol has been used safely in pregnancy despite occasional fetal effects like fetal growth retardation, neonatal bradycardia, and hypoglycemia. Acute variceal bleeding is managed by endoscopically. Vasopressin and octreotide is contraindicated in pregnancy. In extreme cases of variceal bleeding transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt can be considered but has the risk of radiation exposure to the fetus. Ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial infections and coagulopathy treated in the standard way. Vaginal deliveries with assisted, short second stage are preferable, as abdominal surgery is avoided. But in patients with known large varices, caesarean section is recommended to avoid increases in portal pressure and risk of variceal bleeding.

Hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections

In many developed countries, all pregnant women are routinely screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) at the initial booking visit. HBV vaccine can be given safely during pregnancy with little risk to fetus, if needed.[25] Transmission can occur by two mechanism- in utero infection (transplacental) and direct inoculation during delivery (perinatal). Perinatal infection is the predominant mode of transmission. Approximately 10-20% of neonates born to hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), positive mothers and 90% of those born to both HBsAg and hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), positive mothers will become infected with HBV. HBV infection early in life usually results in chronic infection, and 25% of these infected persons will die prematurely from cirrhosis and liver cancer. Chronic HBV infection is more likely in the newborn, when the mother is positive to both HBsAg plus HBeAg and HBV DNA positive with high viral load, associated with 80-90% risk of transmission compared with 10-30% transmission rates in patients with HBsAg positive but HBeAg negative and undetectable viral load.[26]

Immunization with hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) andvaccine at birth can reduce HBV transmission to less than 10% among infants of mothers who are positive for both HBsAg and HBeAg or if the mother is HBeAg negative. All infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers should receive first dose hepatitis B vaccine and single dose HBIG (0.5 mL) within 12 h after birth. Second dose vaccinated at 1-2 months of age and third dose at 6 month of age. After complete vaccinations, testing for HBsAg and hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) should be performed at 9-18 month of age in infants. The hepatitis B vaccine alone is 70-95% effective in preventing HBV transmission. Administration of hepatitis B immunoglobulin and vaccine both within 12 h after birth is 85-95% effective.

In general up to 95% of adults will recover spontaneously and no antiviral treatment is indicated. But 0.5-1.5% of patients who progress to fulminant hepatitis and severe acute HBV infection, nucleoside analogs are recommended. In the last trimester of pregnancy use of lamivudine is safe in HBsAg-positive women may lead to decreased HBV transmission rates, despite its FDA designation as a category C drug.[27] The risk of transmission is similar with normal vaginal delivery and caesarean section. Breastfeeding is not contraindicated.

Pregnant patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) are having presentation similar to non-pregnant patients. The risk for vertical transmission of HCV is low, about 5-10% then perinatal,where the fetus is exposed to large volumes of mother's blood and vaginal fluid during delivery, so it is advised to cut short second stage of labor or if the mother is co-infected with HIV. There are no recommendations regarding mode of delivery. Breastfeeding is not contraindicated but HCV-infected women with cracked or bleeding nipples should abstain from breastfeeding. Antiviral treatment for HCV infection is contraindicated during pregnancy.

Autoimmune liver disease

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is characterized by progressive hepatic parenchymal destruction that may lead to cirrhosis. The natural history of AIH in pregnant women is not fully understood. Pregnancy is not contraindicated in women with autoimmune hepatitis if disease is well controlled and requires stable immuno-suppression throughout pregnancy. Some studies have shown that flares in disease activity are more likely to occur in the first 3 months after delivery, although autoimmune hepatitis might present for the first time during pregnancy.[28] Worsening of AIH in pregnancy is possibly due to changes in various pregnancy related hormones and presence of specific autoantibodies. These include antibodies to soluble liver antigen (SLA)/liver pancreas antibody (LP) and Ro/SSA as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome.[29] Pregnancy does not contraindicate immunosuppressive therapy. Treatment is prednisone and azathioprine (FDA category D at doses <100mg/day). Both are safe in pregnancy. If flares occur, administer steroids or increase in steroid dose. For immunosuppression, azathioprine remains the safest choice.

Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis are autoimmune disease that can overlap with autoimmune hepatitis, leads to destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts. Pregnancy is rare, if occurs carries high risk of prematurity, stillbirth and liver failure. In women with primary biliary cirrhosis, pregnancy can induce new onset pruritus or worsen a preexisting pruritus. Diagnosis is similar to non-pregnant women. UDCA can be used safely for treatment during pregnancy.[30]

Wilson's disease

Wilson disease (WD) is a multisystem rare disorder occurring in 1:30,000 to 1:50,000 persons. It is autosomal recessive disorder of copper transport in liver due to ATP7B gene mutation. Around more than 100 forms of this mutation can cause WD. Defective biliary copper excretion leads to copper deposition in the liver, brain, and kidneys. Hepatic disease may present as chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or fulminant hepatic failure. Patients usually present with high levels of bilirubin, aminotransferases, and Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia and low serum alkaline phosphatase. WD may affect fertility due to hormonal fluctuations. It can result in miscarriage and improper implantation of the embryo due to copper deposition in uterus. In women with known Wilson's disease without treatment, serum copper levels and caeruloplasmin can rise during pregnancy leading to a flare in patient symptoms.[31] The treatment of choice in pregnancy is zinc sulphate (FDA category C) due to efficacy and safety for the fetus. Zinc induces intestinal cell metallothionein that binds to copper and prevents transfer of copper into the blood. The women who are treated with D-Penicillamine (FDA category D) or trientine (FDA category C) before pregnancy require a dose reduction by 25% to 50%, that of pre-pregnancy state.

Liver diseases co-incident with pregnancy

Acute viral hepatitis

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in pregnancy has a clinical presentation and prognosis similar to non-pregnant population and usually self-limited. Mother to child transmission of HAV is very rare. In second half of pregnancy it was associated with premature contraction and premature rupture of membranes.[32] Anti-HAV IgM is test of choice to diagnosis. Treatment of mother is supportive and passive immunoprophylaxis to the new born.

Hepatitis E is prevalent in large areas of Asia, Africa, and Central America. Pregnant women are more vulnerable to hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection than to HAV, HBV and HCV. Hepatitis E usually follows a more severe course in pregnancy, especially in the Indian subcontinent. HEV remains the most prevalent viral cause of fulminant liver failure in pregnancy.[33] Pregnant women are more likely to acquire HEV in the second or third trimester, with a median gestational age of 28 weeks. Reported maternal mortality from fulminant hepatic failure secondary to HEV in pregnancy is 41-54%, with a fetal mortality rate of 69%. When HEV infection occurs in third trimester vertical transmission can result in neonatal massive hepatic necrosis and death in up to 33% of neonates. Vertical transmission to the new born occurs in 50% cases if mother is viremic at the time of delivery. Vertical transmission has been documented by specific HEV IgM in cord blood and virus isolation is done by PCR. In-utero transmission of HEV to the fetus might add further toxic metabolites to the maternal circulation, resulting in increased maternal morbidity and mortality.[35] Management is conservative supportive including intensive unit care. Remarkably, delivery does not affect maternal outcome.

Herpes simplex viral (HSV) hepatitis is a rare condition. During pregnancy 2% of women are infected with HSV infection. But can be very fatal when primary infection occurs in pregnancy because it is associated with 40% risk of fulminant hepatic failure and death. It usually occurs during third trimester presenting as severe or fulminant “anicteric” hepatitis. Recurrent HSV infections usually presents as genital mucocutaneous lesions. Infection near the time of delivery increases the infection transmission to the fetus. The common laboratory findings are normal serum bilirubin levels with raised aminotransferases, thrombocytopenia, leucopenia, and coagulopathy. Computed tomography shows multiple hypoechoic areas of necrosis within the liver. Liver biopsy provides the definitive evidence of HSV hepatitis. Mucocutaneous lesions associated with HSV infection might be present only in 50% of cases. Treatment with acyclovir is associated with improved survival rate. For severe primary HSV infection or if there is high clinical suspicion and there is delay in confirmatory results intravenous acyclovir is treatment of choice.

Gall stones and biliary disease

The prevalence of gallstones in pregnancy is 18.4-19.3% in multiparous women and 6.9-8.4% in nulliparous women.[36] The etiology is multifactorial. Increased estrogen levels, especially in second and third trimesters lead to increased cholesterol secretion and supersaturation of bile. The increased progesterone levels cause decrease in small intestinal motility. Also, fasting and postprandial gallbladder volumes are larger, and emptying time is reduced. The large residual volume of supersaturated bile in the pregnant woman leads to biliary sludge and the formation of gallstones.

Pregnant women with gallstones may present with right upper quadrant pain that may radiate to the flank, scapula or shoulder. There may nausea, vomiting, anorexia, fatty food intolerance, and low-grade fever. Conservative medical management is recommended especially during first and third trimesters, in which surgical intervention may increase risk of abortion or premature labor, respectively. Medical management involves intravenous fluids, correction of electrolytes, bowel rest, pain management, and broad spectrum antibiotics. Symptomatic patients in the first or second trimester should undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy because biliary colic will recur in 50% of pregnant patients before delivery and the pregnancy outcome is better compared with medical therapy.[37]

For patients presenting with intractable biliary colic, severe acute cholecystitisis not responding to conservative measures or acute gallstone pancreatitis, cholecystectomy is indicated despite the pregnant state. An impacted common bile duct stone and worsening gallstone pancreatitis are indications to proceed to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, sphincterotomy, and stone extraction under antibiotic coverage. Minimization of fluoroscopy and ionizing radiation to the fetus is essential.

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Budd-Chiari syndrome is a rare condition caused by outflow obstruction of the hepatic veins or the terminal portion of the inferior vena cava. Most cases occur during post partum period. The 25% of pregnant women with Budd-Chiari syndrome have ahypercoaguable state with predisposing condition, such as factor V Leiden, antithrombin III, protein C and S deficiency, or presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.[38] In patients with known Budd-Chiari syndrome there is risk of exacerbation during pregnancy due to increased concentrations of female sex hormones. Clinical features include right upper quadrant pain, ascites and jaundice (in approx.50%). Treatment is to investigate for thrombophilias and complete anticoagulation throughout pregnancy and puerperium. Porto-caval and mesocaval shunting, or liver transplantation is required in extreme cases.

CONCLUSION

Liver disease in pregnancy can present with subtle changes in liver biochemical profile or with fulminant hepatic failure. In pregnancy these causes serious adverse effects on both mother and fetus. Now days due to good research work and better understanding of the pathogenesis of these disorders, new treatment option and high standard clinical care, the maternal and fetal mortality has decreased.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ch’ng CL, Morgan M, Hainsworth I, Kingham JG. Prospective study of liver dysfunction in pregnancy in Southwest Wales. Gut. 2002;51:876–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamay AG, Kuşçu NK. Hyperemesis gravidarum: Current aspect. J ObstetGynaecol. 2011;31:708–12. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2011.611918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodwin TM. Hyperemesis gravidarum. ObstetGynecolClin North Am. 2008;35:401–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan PB, Gücer F, Sayin NC, Yüksel M, Yüce MA, Yardim T. Maternal serum cytokine levels in women withhyperemesis gravidarum in the first trimester of pregnancy. FertilSteril. 2003;79:498–502. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jewell D, Young G. Withdrawn: Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000145.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2004;40:467–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondrackiene J, Kupcinskas L. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy-current achievements and unsolved problems. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5781–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marciniak B, Kimber-Trojnar Z, Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B, Patro-Małysza J, Trojnar M, Oleszczuk J. [Treatmentof obstetriccholestasiswith polyunsaturated phosphatidylcholineandursodeoxycholic acid] Ginekol Pol. 2011;82:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ropponen A, Sund R, Riikonen S, Ylikorkala O, Aittomäki K. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy as an indicator of liver and biliary diease: Apopulation-based study. Hepatology. 2006;43:723–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steegers EA, von Dadelszen P, Duvekot JJ, Pijnenborg R. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2010;376:631–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton JR, Sibai BM. Prediction and prevention of recurrent preeclampsia. ObstetGynecol. 2008;112:359–72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181801d56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meads CA, Cnossen JS, Meher S, Juarez-Garcia A, ter Riet G, Duley L, et al. Methods of prediction and prevention of pre-eclampsia: Systematic reviews of accuracy and effectiveness literature with economic modelling. Health Technol Assess. 2008;12:1–270. doi: 10.3310/hta12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Meher S. Drugs for treatment of very high blood pressure during pregnancy (Cochrane Review) The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001449.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pryde PG, Mittendorf R. Contemporary usage of obstetric magnesium sulfate: Indication, contraindication, and relevance of dose. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:669–73. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b43b0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulikov AV, Spirin SV, Blauman SI. [Clinicopathologic characteristics of HELLP-syndrome].[Article in Russian] AnesteziolReanimatol. 2010;6:87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducarme G, Bernuau J, Luton D. [Liver and preeclampsia] Ann FrAnesthReanim. 2010;29:e97–e103. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salahuddin S, Lee Y, Vadnais M, Sachs BP, Karumanchi SA, Lim KH. Diagnostic utility of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and soluble endoglin in hypertensive diseases of pregnancy. Am J ObstetGynecol. 2007;197:28.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihu D, Costin N, Mihu CM, Seicean A, Ciortea R. HELLP syndrome–a multisystemic disorder. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onyangunga OA, Moodley J. Managing pregnancy with HIV, HELLP syndrome and low platelets. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26(1):133–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin JN, Jr, Rose CH, Briery CM. Understanding and managing HELLP syndrome: The integral role of aggressive glucocorticoids for mother and child. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:914–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woudstra DM, Chandra S, Hofmeyr GJ, Dowswell T. Corticosteroids for HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets) syndrome in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008148.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ibdah JA. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: An update on pathogenesis and clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7397–404. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i46.7397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams J, Mozurkewich E, Chilimigras J, Van De Ven C. Critical care in obstetrics: Pregnancy-specific conditions. Best Pract Res ClinObstetGynaecol. 2008;22:825–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hay JE. Liver disease in pregnancy. Hepatology. 2008;47:1067–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Devarbhavi H, Kremers WK, Dierkhising R, Padmanabhan L. Pregnancy-associated acute liver disease and acute viral hepatitis: Differentiation, course and outcome. J Hepatol. 2008;49:930–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.vanZonneveld M, van Nunen AB, Niesters HG, de Man RA, Schalm SW, Janssen HL. Lamivudine treatment during pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:294–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Food and Drug Administration, FDA. Available from: http://www.fda.gov.Drugs/DrugsSafety/Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patientsand Providers/ucm111085 .

- 28.Heneghan MA, Norris SM, O’Grady JG, Harrison PM, McFarlane IG. Management and outcome of pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:97–102. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schramm C, Herkel J, Beuers U, Kanzler S, Galle PR, Lohse AW. Pregnancy in autoimmune hepatitis: Outcome and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:556–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poupon R, Chrétien Y, Chazouillères O, Poupon RE. Pregnancy in women with ursodeoxycholic acid-treated primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:418–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sternlieb I. Wilson's disease and pregnancy. Hepatology. 2000;31:531–2. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elinav E, Ben-Dov IZ, Sharpia Y, Daudi N, Adler R, Shouval D, et al. Acute hepatitis A infection in pregnancy is associated with high rates of gestational complications and preterm labor. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(4):1129–34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banait VS, Sandur V, Parikh F, Murugesh M, Ranka P, Ramesh VS, et al. Outcome of acute liver failure due to acute hepatitis E in pregnant women. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhatia V, Singhal A, Panda SK, Acharya SK. A 20-year single-center experience with acute liver failure during pregnancy: Is the prognosis really worse? Hepatology. 2008;48:1577–85. doi: 10.1002/hep.22493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mushahwar IK. Hepatitis E virus: Molecular virology, clinical features, diagnosis, transmission, epidemiology, and prevention. J Med Virol. 2008;80:646–58. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilat T, Konikoff F. Pregnancy and the biliary tract. Can J Gastroenterol. 2000;14(Suppl D):55D–59D. doi: 10.1155/2000/932147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu EJ, Curet MJ, El-Sayed YY, Kirkwood KS. Medical versus surgical management of biliary tract disease in pregnancy. Am J Surg. 2004;188:755–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rautou PE, Plessier A, Bernuau J, Denninger MH, Moucari R, Valla D. Pregnancy: A risk factor for Budd-Chiari syndrome? Gut. 2009;58:606–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.167577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]