Abstract

Background:

Evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white blood cell (WBC) count and glucose and protein concentrations is used to assess the probability of the presence of central nervous system (CNS) infection. Although normal values are well established for CSF cell counts and protein and glucose contents in children and adults, this is not the case for neonates.

Aims:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the composition of noninfected CSF obtained by nontraumatic lumbar puncture in neonates (age<28 days), specifically distinguishing CSF profiles of those term babies compared with those premature infants.

Materials and Methods:

The CSF samples obtained by lumbar puncture from 120 neonates were examined by routine procedures.

Results:

By comparing CSF parameters between term gestation neonate group with premature neonate one, nontraumatic puncture, there was no statistically significant difference (P<0.05) in the mean WBC (P=0.6). The mean protein concentration was significantly greater in those premature neonates (P<0.04). The mean glucose concentration was also analogous in both groups (P=0.5).

Conclusion:

The CSF profile, like any other laboratory determination, should be evaluated within the clinical context of the individual case.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid parameters, preterm neonates, term neonates

INTRODUCTION

The cumulative incidence of meningitis is highest in the 1st month of life and is higher in preterm neonates than term neonates.[1] It is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in neonatal age group. Evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white blood cell (WBC) count, and glucose and protein concentrations is used to assess the probability of the presence of central nervous system (CNS) infection. Although normal values are well-established for CSF cell counts and protein and glucose contents in children and adults, this is not the case for neonates.[2,3] There is very scanty information regarding the range of CSF values in high-risk term and preterm neonates with noninfected CSF obtained by nontraumatic puncture, with no red blood cells (RBC/mm3 = 0). When faced with the need to make therapeutic decisions on the interpretation of CSF parameters, the clinicians often use the normal “cutoff” values for CSF parameters in preterm neonates are ≤25 WBC/mm3, ≥24 mg glucose/dL, and ≤170 mg protein/dL.[4]

AIMS AND OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the composition of noninfected CSF obtained by nontraumatic lumbar puncture (RBC = 0/mm3) in neonates (age < 28 days), specifically distinguishing CSF profiles of those term babies compared with those premature infants, and to compare CSF values between nontraumatic and traumatic puncture up to 500 RBC/mm3 in term neonates with the preterm ones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ours is a retrospective study done by reviewing the CSF chart of the newborn babies who underwent lumbar puncture between January 2012 and September 2012.

The CSF samples obtained by lumbar puncture from 120 neonates were examined by routine procedures. The CSF WBC count was performed in improved Neubauer hemocytometer, the CSF protein and glucose were measured by enzymatic method in semiautomated biochemical analyzer.

Inclusion criteria

(1) Age up to 28 days, 2(a) nontraumatic puncture (RBC = 0/mm3), or ii 2(b) traumatic puncture up to 500 RBC/mm3, and (3) accessible clinical data.

Informed consent was taken from each and every patient party before including the patients in our study.

Exclusion criteria

(1) Nontraumatic hemorrhagic CSF, (2) neonates having clinical evidence of infection (clinical information was obtained retrospectively from chart review).

RESULTS

Among the 120 CSF samples obtained by lumbar puncture, 25 (term 10, preterm 15) were excluded according to excluding criteria. Therefore the cytological parameters, protein and glucose values were studied in 50 term babies and 45 preterm babies. Ten CSF samples from the term and five samples from the preterm neonates were found to be traumatic (RBC < 500/mm3).

Standard statistical methods (Student t-test) were used in evaluation and P < 0.05 was considered as statistical significant difference.

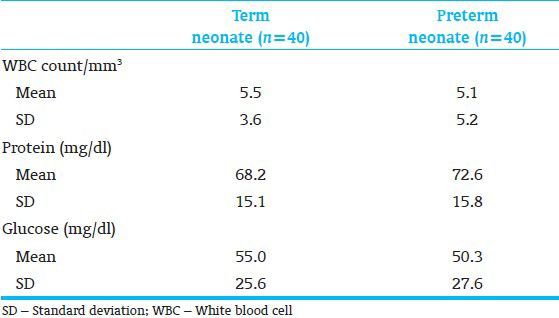

By comparing CSF parameters between term gestation neonate group with premature neonate one, nontraumatic puncture, there was no statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in the mean WBC (P = 0.6). The mean protein concentration was significantly greater in those premature neonates (P < 0.04). The mean glucose concentration was also analogous in both groups (P = 0.5) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Cerebrospinal fluid parameters in term vs preterm neonates

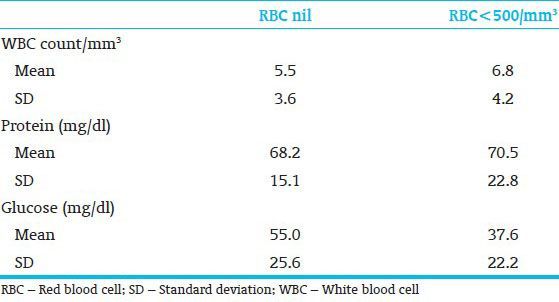

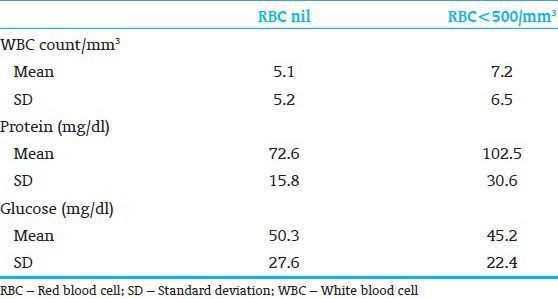

By comparing CSF parameters in traumatic puncture with nontraumatic puncture performed on full-term gestation neonates, the mean glucose concentration was significantly lesser in the traumatic puncture group (P < 0.02) [Table 2]. Regarding premature neonates, the mean protein concentration was significantly greater in the traumatic puncture group (P < 0.05). The glucose concentration was also lesser in these children but the difference was not significant [Table 3].

Table 2.

Cerebrospinal fluid parameters in term neonates; nontraumatic vs traumatic

Table 3.

Cerebrospinal fluid parameters in preterm neonates; nontraumatic vs traumatic

DISCUSSION

The proper interpretation of CSF results depends on knowledge of normal values in the group of patients being evaluated. Several authors have pointed out that there is an acceptable variability in the CSF profile, especially CSF WBC count in neonates. Furthermore, early detection of neonatal meningitis is a continuing concern in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Several studies showed that the average CSF WBC count is 6-7 cell/mm3 in neonates, but these studies evaluated healthy neonates;[5] this is very close to the results we found (5.5/mm3 and 5.1/mm3). However, greater number of cells may be normal (28 WBC/mm3). Luz,[6] studying a full-term gestation and normal neonate group, found that the CSF WBC count can be up to 12 WBC/mm3 and the protein concentration can be up to 120 mg/dl; although this author studied CSF samples with up to 600 RBC/mm3, these values are close to ours [Tables 1 and 2].

The mean protein concentration was significantly greater in the premature group and this is probably due to the more immature blood-brain barrier in these children when compared with term babies (P < 0.04).[7] This parameter in both groups was slightly lesser than those previously reported in the literature.[8] The mean glucose concentration was just the same in both groups.

When we compared traumatic puncture with nontraumatic puncture, we found that the mean glucose concentration was significantly lesser when the puncture was traumatic (P < 0.02) in term neonates; in premature neonates the mean glucose concentration was also lesser in the traumatic puncture group, but the difference was not significant (P < 0.20); it is possible that some of the patients included in the group of traumatic puncture were in fact patients with CNS hemorrhage what could explain the lower glucose concentrations[2]; the mean protein concentration was greater in children who underwent traumatic puncture in the premature neonate group (P < 0.05). These data show how traumatic puncture, even with RBC up to 500/mm3, interferes on CSF analysis and changes its parameters.

CONCLUSION

The CSF profile, like any other laboratory determination, should be evaluated within the clinical context of the individual case. The mean CSF protein concentration is significantly greater in those premature neonates compared with those full-term gestation neonates. Traumatic puncture, even up to 500 RBC/mm3, interferes on CSF parameters. But there are certain limitations in our study like small number of samples(n=95), short duration, single centre study applied on healthy individuals. A prospective study using mortality and neurodevelopmental follow up will better define the utility of CSF parameters in the premature neonate.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Overall JC., Jr Neonatal bacterial meningitis. Analysis of predisposing factors and outcome compared with matched control subjects. J Pediatr. 1970;76:499–511. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishman RA. CSF findings in diseases of the nervous system. In: Fishman RA, editor. Cerebrospinal Fluid in Diseases of the Nervous System. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1992. pp. 253–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarff LD, Platt LH, McCracken GH., Jr Cerebrospinal fluid evaluation in neonates: Comparison of high-risk infants with and without meningitis. J Pediatr. 1976;88:473–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson J, Shilkofski N. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2005. The Harriet Lane Handbook; p. 557. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyers HJ, Bakker JC. The cerebrospinal fluid of a at term borne neonate. Maandschr Kindergenceeskd. 1954;22:253–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luz BR. Tese. São Paulo: Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo; 1972. Contribuiçãopara o estudo da xantocromia do líquidocefalorraqueano de recém-nascidosnormais. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Albuquerque Diniz EM, Spina-França Netto A, Livramento JA, Machado LR, Ayres Castilho E, Bahía Corradini H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid of premature newborn infants during the neonatal period. II. Protein study. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 1982;39:473–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaz FA, Livramento JA, Spina-França A. Cerebrospinal fluid in the healthy preterm newborn infant. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1977;35:183–8. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x1977000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]