Abstract

The first total synthesis of the C18-norditerpenoid aconitine alkaloid neofinaconitine and relay syntheses of neofinaconitine and 9-deoxylappaconitine from condelphine are reported. A modular, convergent synthetic approach involves initial Diels–Alder cycloaddition between two unstable components, cyclopropene 10 and cyclopentadiene 11. A second Diels–Alder reaction features the first use of an azepinone dienophile 8, with high diastereofacial selectivity achieved via rational design of the siloxydiene component 36 with a sterically-demanding bromine substituent. Subsequent Mannich-type N-acyliminium and radical cyclizations provide the complete hexacyclic skeleton 33 of the aconitine alkaloids. Key endgame transformations include installation of the C8-hydroxyl group via conjugate addition of water to a putative strained bridghead enone intermediate 45, and one-carbon oxidative truncation of the C4 sidechain to afford racemic neofinaconitine. Complete structural confirmation was provided by a concise relay synthesis of (+)-neofinaconitine and (+)-9-deoxylappaconitine from condelphine, with X-ray crystallographic analysis of the former clarifying the NMR spectral discrepancy between neofinaconitine and delphicrispuline, which were previously assigned identical structures.

INTRODUCTION

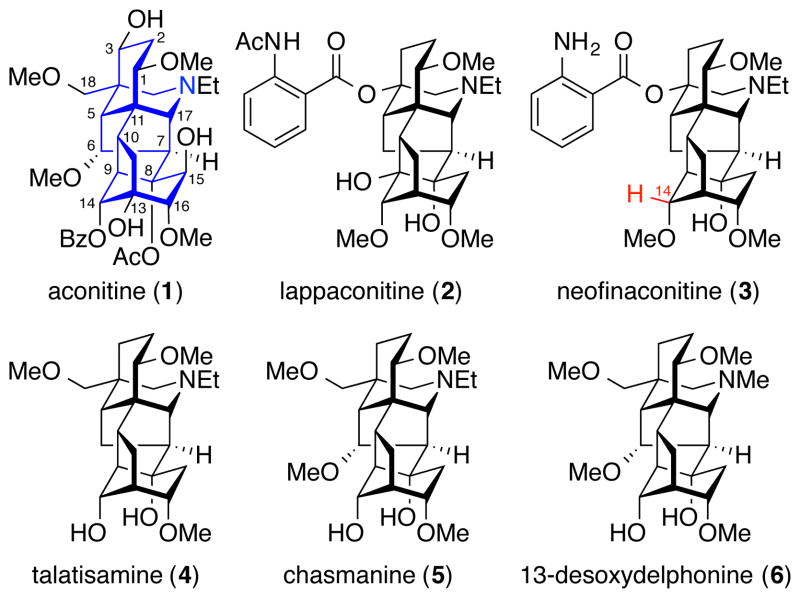

Plants from the genera Aconitum and Delphinium have been used for centuries in traditional Chinese and Japanese folk medicines as antiarrhythmics and analgesics.1 Although the raw leaves and roots are quite toxic, high-temperature preparations have been applied to reduce their toxicity and render them clinically useful. The long history of these plants as medicines has piqued the interest of natural product chemists, leading to the isolation and characterization of a number of aconitum and delphinium alkaloids.2 Some of the most biologically active isolates are in the norditerpenoid alkaloid class, which is further subdivided based on the presence [C19-norditerpenoid, e.g., aconitine (1)] or absence [C18-norditerpenoid, e.g., lappaconitine (2)] of the C18 carbon (Figure 1). The isolation3 and identification4 of these alkaloids enabled pharmacological studies that have revealed their roles as ion-channel modulators.5 Notably, one of these alkaloids, lappaconitine (Allapinin), has been commercialized as an antiarrhythmic drug.6 The structure of the C19-norditerpenoid alkaloids was first elucidated by Wiesner and coworkers, who also completed the first total synthesis of a member of this group, talatisamine (4).7 They subsequently also achieved the total syntheses of chasmanine (5)8 and 13-deoxydelphonine (6)8b,9 via an alternative strategy that provided improved chemoselectivity at key steps. Despite numerous synthetic attempts,10 these remain the only published total syntheses of norditerpenoid alkaloids to date. The potent biological activity and absence of a convergent approach to these alkaloids make them attractive targets for synthesis.

Figure 1.

Structures of selected C19- and C18-norditerpenoid alkaloids. Neofinaconitine and delphicrispuline have both been assigned the same structure (3), but have distinct chemical shifts reported for the C14 proton (neofinaconitine δ 3.68, delphicrispuline δ3.45 ppm, CDCl3).11

Neofinaconitine (1) was chosen as our initial target for total synthesis based on two considerations. First, two groups independently reported the isolation of natural products with the same proposed structure, neofinaconitine (Jiang) and delphicrispuline (Ulubelen).11 Examination of the reported spectral data revealed a discrepancy in the chemical shift of the C14 proton (neofinaconitine δ 3.68, delphicrispuline δ 3.45 ppm, CDCl3). Therefore, total synthesis of the proposed structure would help elucidate the identity of the natural product (referred to herein as neofinaconitine). Second, biological studies of neofinaconitine have not been reported, primarily due to its scarcity. However, due to its close structural similarity to the natural product lappaconitine, which exhibits intriguing biological activities, such studies are of considerable interest and would be enabled by efficient synthetic access.

Herein, we report the first total synthesis of neofinaconitine, featuring sequential, convergent cyclopropene/cyclopentadiene and azepinone/siloxydiene Diels–Alder cycloadditions to assemble a key cyclization substrate, followed by successive Mannich-type N-acyliminium (Speckamp) and radical cyclizations. Structural insights were used to reengineer the siloxydiene substrate in the azepinone Diels–Alder cyclo-addition to achieve improved diastereofacial selectivity. An expedient relay synthesis from commercially available condelphine was also developed to access (+)-neofinaconitine and (+)-9-deoxylappaconitine (2), confirming stereochemical assignments in the totally synthetic material. X-ray crystallographic analysis of the relay material unambiguously confirmed the structure of neofinaconitine, thus resolving the NMR spectral discrepancy and indicting that the structure of delphicrispuline requires reconsideration.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Synthetic Strategy

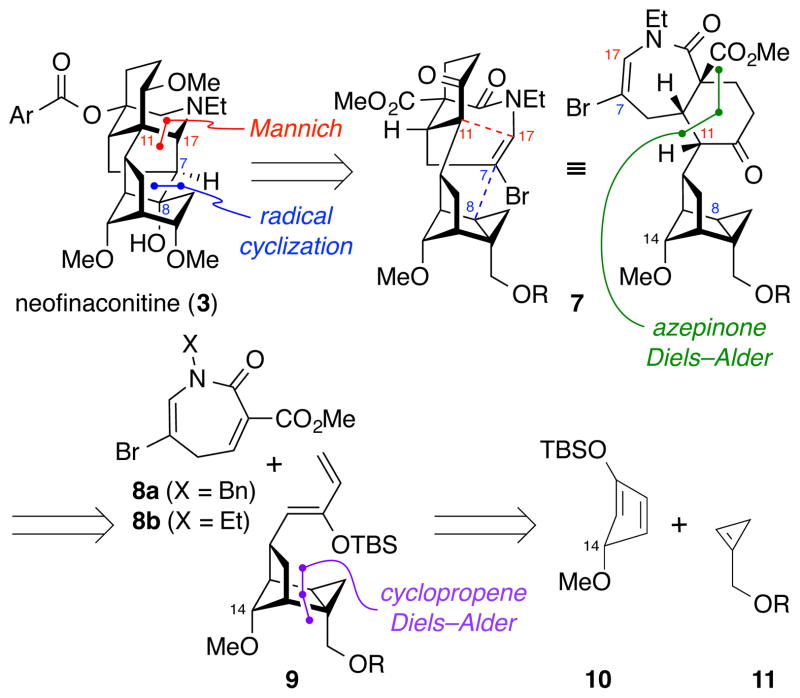

Our overall approach to the synthesis of neofinaconitine (3) is outlined in Figure 2. The hexacyclic scaffold of 3 is simplified retrosynthetically by late-stage formation of the C11–C17 and C7–C8 bonds. The [5.4.0]-bicycloazepine ring system in 7 arises from a Diels–Alder cycloaddition12 between dihydroazepinone 8 and siloxydiene 9. Although use of an azepinone such as 8 as a dienophile has not, to our knowledge, been reported in the literature, the convergence of this approach made it an attractive avenue for investigation. The fused cyclopropane 9 is prepared by another unusual Diels–Alder cycloaddition between cyclopentadiene 10 and cyclopropene 11.13 While this approach rapidly builds complexity, it is not without significant challenges. A contrasteric facial approach of dienophile 11 would be required to give the desired stereochemistry at C14. Furthermore, cyclopentadienes are known to dimerize readily and to undergo 1,5-hydrogen shifts,14 resulting in scrambled substitution patterns. However, a recent example by Gleason and coworkers15 demonstrated that the presence of a silyl ether significantly retards these hydrogen shifts. Although the dienophiles approach exclusively from the sterically more-accessible face of the diene in that report, contrasteric cycloadditions of heteroatom-substituted cyclopentadienes have been reported elsewhere,16 and selectivity has been shown to be substrate dependent.16c

Figure 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis of neofinaconitine (3) via late-stage formation of the C11–C17 and C7–C8 bonds and sequential Diels–Alder cycloadditions. Ar = 2-aminophenyl; R = TIPS, triisopropylsilyl.

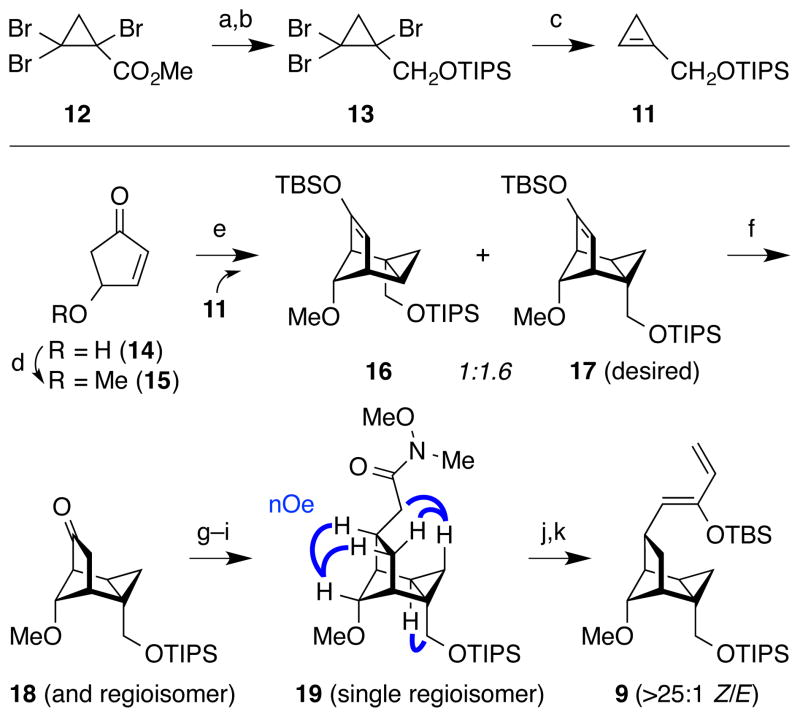

Cyclopropene/Cyclopentadiene Diels–Alder Cycloaddition

Synthesis of the cyclopropene component commenced with known tribromocyclopropane 12, available in 3 steps from methyl acrylate17 (Figure 3). Ester reduction with DIBAL followed by silyl protection provided cyclopropene precursor 13. Lithium–halogen exchange of 13 with 2 equiv MeLi followed by aqueous quench of the resulting vinyl anion gave cyclopropene 11, which could be isolated and was used immediately due to rapid Alder-ene dimerization. The cyclopentadiene component was prepared from the known cyclopentenone 14,18 available in one step from furfuryl alcohol. Methylation of the allylic alcohol19 (Ag2O, MeI) provided ether 15. Enolization–silylation19 (TBSOTf, Et3N) of 15 with aqueous workup provided an intractable mixture of cyclopentadiene dimers. However, when cyclopropene 11 was introduced directly into the cyclopentadiene reaction mixture prior to workup, the desired cycloadduct 17 was obtained as an inseparable 1.6:1 mixture with the undesired regioisomer 16, along with small amounts of other isomers.20,21 Notably, this reaction favored contrasteric approach of the cyclopropene dienophile to the cyclopentadiene (5.6:1).21,22 Attempts to improve the regioisomeric ratio through the use of a methyl enoate derived directly from ester 12 provided only a complex mixture of products with no indication of successful cycloaddition. Therefore, the mixture of 16 and 17 was taken on via a 4-step route involving NaOH hydrolysis of the silyl ether to form ketone 18, Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons olefination,23 Pd-catalyzed stereoselective hydrogenation, and AlMe3-mediated Weinreb amide formation.24 At this point, the desired Weinreb amide 19 could be separated from the regioisomeric mixture obtained from the cyclopropene/cyclopentadiene Diels–Alder reaction. Treatment with vinylmagnesium bromide25 then KHMDS, TBSOTf26 provided Z-siloxydiene 9, the 4π-component for the second key Diels–Alder cycloaddition below.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of fused tricyclic cyclopropane 9 via cyclopropene Diels–Alder cycloaddition. a) DIBAL, CH2Cl2, −78 °C to 20 °C; b) TIPSCl, imidazole, CH2Cl2, 72% over 2 steps; c) MeLi, THF, −78 °C; d) MeI, Ag2O, CH2Cl2, 75%; e) 11, TBSOTf, Et3N, 0 °C; f) NaOH, THF/H2O; g) methyl diethylphosphonoacetate, KHMDS 0 °C to 23 °C, reflux; h) H2, Pd/C, EtOAc; i) N,N-dimethylhydroxylamine hydrochloride, AlMe3, THF, 39% over 6 steps from 13 (single isomer); j) vinylmagnesium bromide, 0 °C; k) TBSOTf, KHMDS, THF, −78 °C, 77% over 2 steps. DIBAL = diisobutylaluminum hydride; KHMDS = potassium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide; TBS = tert-butyldimethylsilyl; Tf = trifluoromethanesulfonyl; TIPS = triisopropylsilyl.

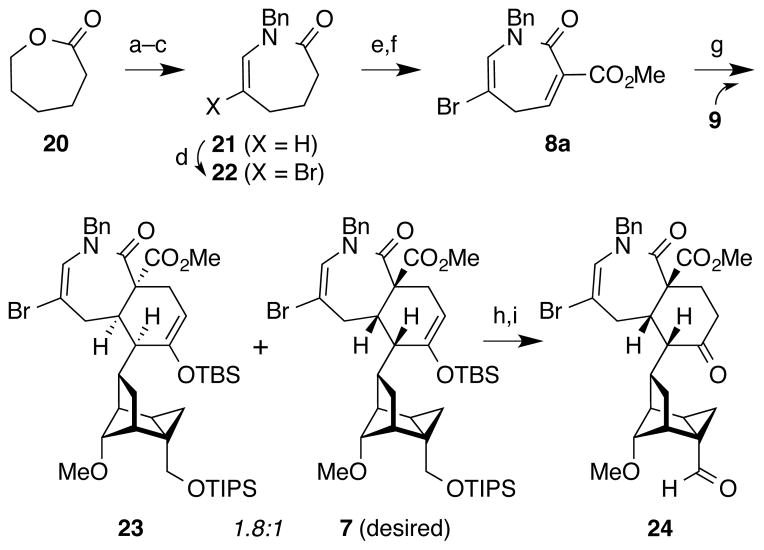

Azepinone/Siloxydiene Diels–Alder Cycloaddition

Synthesis of the azepinone 2π-component began with commercially available ε-caprolactone 20 (Figure 4). Lactone aminolysis27 (BnNH2, neat, 120 °C) was followed by Parikh–Doering oxidation28 of the resulting primary alcohol and acid-catalyzed intramolecular enamine formation to afford 21. Halogenation with bromine then provided vinyl bromide 22 (Br2, Et3N). Sequential treatment of the lithium enolate of 22 with ClCO2Me and PhSeCl, followed by selenide oxidation/elimination (H2O2)29 then furnished azepinone dienophile 8a.

Figure 4.

Synthesis of cyclopropane carboxaldehyde 24 via azepinone Diels–Alder cycloaddition. a) BnNH2, 120 °C, 78%; b) SO3·pyridine, Et3N, CH2Cl2/DMSO, 93%; c) TsOH, toluene, 110 °C, 77%; d) Br2, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 86%; e) LiHMDS, ClCO2Me, PhSeCl, −78 °C to 20 °C; f) H2O2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 99% over 2 steps; g) 10, Sc(OTf)3, PhMe, 69%; h) TBAF, THF, 77%; i) IBX, CH3CN, sonication, 87% combined yield from 23 and 7, 31% isolated yield of 24. LiHMDS = lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide; Ts = p-toluenesulfonyl.

At this juncture, both the 4π- and 2π-components (9 and 8a) were in hand for the convergent Diels–Alder cycloaddition to produce the [5.4.0]-bicycloazepine ring system. Notably, the use of a dihydroazepine as a dienophile was without literature precedent, and so the expected regio-, endo/exo-, and facial selectivity of this transformation was unclear, especially in the setting of a complex polycyclic diene such as 9. After extensive experimentation with thermal and Lewis-acid catalysis in a variety of solvents, we found that, when a solution of dienophile 8 and diene 9 in toluene was treated with Sc(OTf)3, the Diels–Alder cycloaddition provided complete regio- and endo-selectivity. However, the product was obtained as an inseparable 1.8:1 mixture of undesired stereofacial cycloadduct 23 and desired cycloadduct 7 in 69% combined yield.21 Silyl deprotection (TBAF, THF) followed by oxidation (IBX, CH3CN, sonication) and separation of the diastereomers provided aldehyde 24 in 31% yield, along with 56% of the undesired diastereomer (not shown). Although this sequence favored the undesired distereomer, the rapid increase in complexity provided by this approach enabled exploration of the installation of the remaining C11–C17 and C7–C8 bonds.

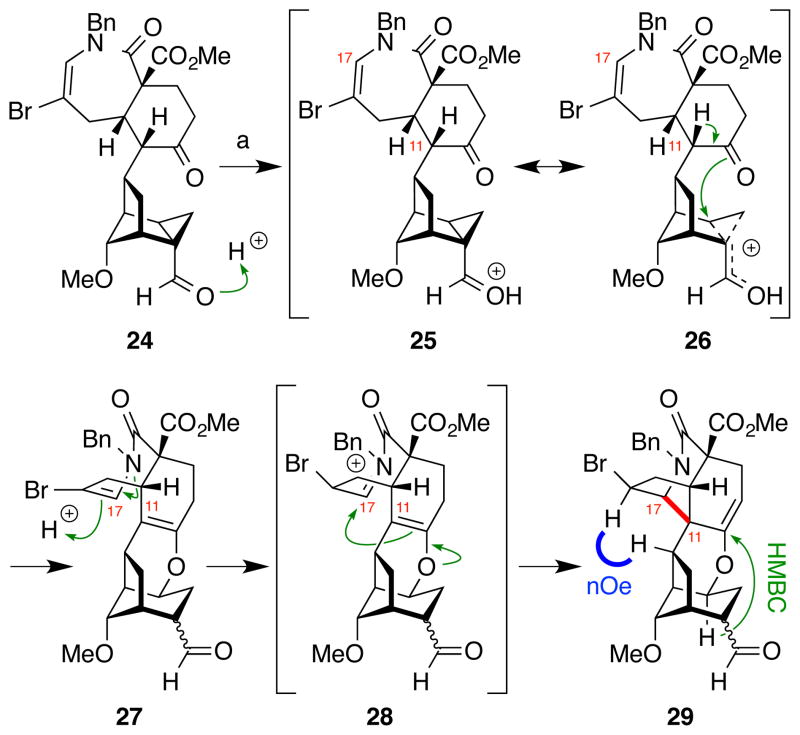

C11–C17 Bond Formation by Mannich-type N-Acyliminium Cyclization

Next, the C11–C17 bond was formed via Mannich-type acid-catalyzed nucleophilic attack of an enol at C11 onto an N-acyliminium at C17 (Figure 5). When cyclopropane carboxaldehyde 24 was treated with any of a number of Lewis or Brønsted acids, cyclic enol ether 27 formed quickly and could be recovered from the reaction mixture. Presumably, this product is formed via activation of the aldehyde as cyclopropylcarbinyl oxocarbenium 25 and its resonance form 26. Regioselective intramolecular attack by the ketone oxygen upon this cation then forms the observed cyclic enol ether 27.21 Ultimately, use of the much stronger acid Tf2NH not only effected this cyclopropane rupture, but also catalyzed formation of the key C11–C17 bond through protonation of the enamide in 27 to give putative N-acyliminium intermediate 28, which then underwent nucleophilic attack by the C11 enol to provide enol ether 29, whose structure was confirmed based on extensive 1D NOE and 2D NMR analyses.21

Figure 5.

Mannich-type N-acyliminium cyclization of 24 to form the key C11–C17 bond in 29. a) Tf2NH, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 71%.

C7–C8 Bond Formation by Radical Cyclization

To complete the synthesis of the hexacyclic skeleton of the norditerpenoid alkaloids, the cyclic enol ether in 29 needed to be cleaved. However, this enol ether proved to be quite robust, withstanding standard aqueous acidic conditions even at elevated temperature. More extreme conditions (12 N HCl, 60 °C) resulted in hydrolysis of both the methyl ester and methyl ether, but no products were detected in which the enol ether had been cleaved. Interestingly, the vinyl proton in 29 appeared at 5.4 ppm in the 1H-NMR spectrum. This unusually downfield vinyl ether signal could arise from poor orbital overlap of the oxygen lone pair and the π system of the alkene, and suggested that hydrolysis would continue to be a challenge.

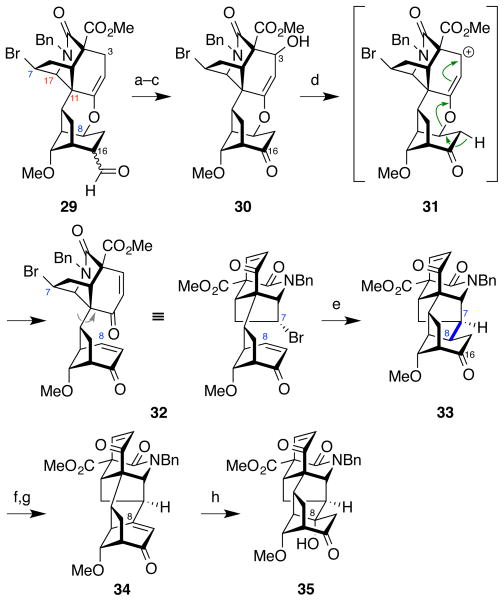

Thus, alternative methods to cleave the enol ether were investigated and oxidative elimination of the enol ether ultimately proved to be an effective route (Figure 6). The C16 aldehyde sidechain in 29 was subjected to a two-step, one-carbon truncation30 (TBSOTf, Et3N; then OsO4, PhI(OAc)2, 2,6-lutidine) followed by C3 allylic oxidation adjacent to the enol ether (CAN, CH3CN/H2O) to provide keto-alcohol 30. Activation of the allylic alcohol as a mesylate (MsCl, Et3N) then generated bis-enone 32, presumably by elimination of the enol-ether oxygen via allyl cation 31. Site-selective intramolecular radical conjugate addition of a bromide-derived radical at C7 into the enone at C8 (Bu3SnH, AIBN) provided the desired hexacycle 33.

Figure 6.

Intramolecular radical conjugate addition of 32 to form the key C7–C8 bond in 33 and completion of the carbon skeleton of the C19-norditerpenoid alkaloids 35. a) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 86%; b) OsO4, PhI(OAc)2, 2,6-lutidine, THF/H2O, 74%; c) Ce(NH4)2(NO3)6, CH3CN/CH2Cl2/H2O, 50 °C; d) MsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 57% over 2 steps; e) Bu3SnH, AIBN, PhH, 80 °C, 86%; f) LiHMDS, PhSeCl, THF, −78 °C, 75%; g) H2O2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 90%; h) AcOH, THF, H2O, 77%. AIBN = 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionitrile); Ms = methanesulfonyl.

Completion of the Hexacyclic Skeleton of the C19-Norditerpenoid Alkaloids

Finally, we sought to install the requisite C8-hydroxyl group found in the aconitine alkaloids. The paucity of precedents for this formal C–H oxidation led us to pursue an unconventional strategy that exploited the inherent reactivity embedded within the molecular framework. A 3-step sequence involving α-selenylation of the C16-ketone (LiHMDS, PhSeCl), selenoxide elimination (H2O2) to give the highly-strained bridghead enone 34, and immediate trapping with water (aq THF, AcOH) provided the tertiary alcohol 35, comprising the complete hexacyclic skeleton of the C19-norditerpenoid alkaloids. The structure was confirmed by extensive 2D NMR analysis.21

Completion of the hexacyclic skeleton of the norditerpenoid alkaloids was a welcome achievement. However, exploration of the installation of the remaining functional groups was hampered by low material throughput resulting primarily from the poor diastereoselectivity of the azepinone/siloxydiene Diels–Alder cycloaddition between 8 and 9 (Figure 4). Therefore we embarked upon a second-generation synthesis to enable the total synthesis of neofinaconitine.

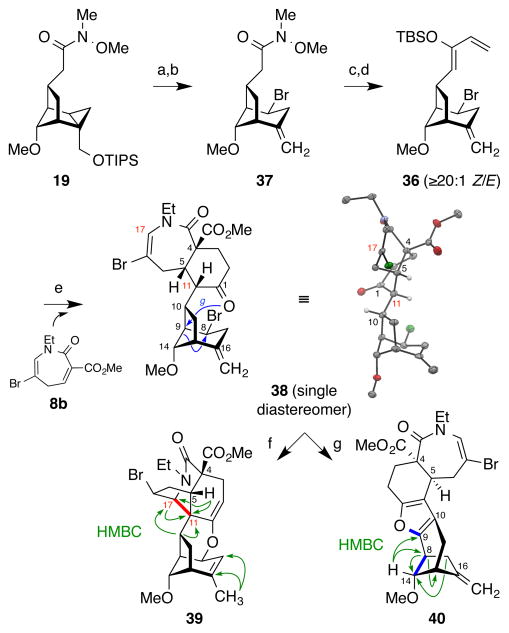

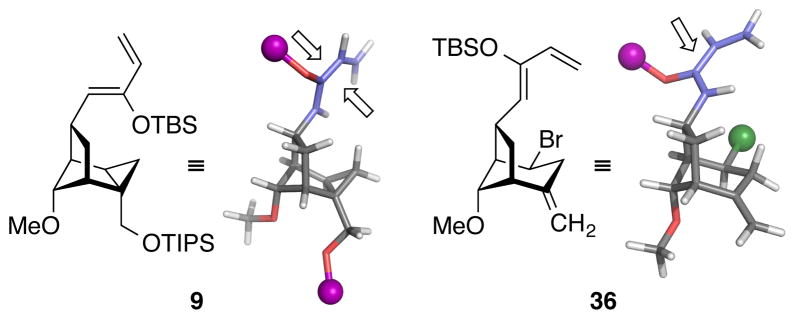

Enhanced Azepinone/Siloxydiene Diels–Alder Diastereo-selectivity through Rational Substrate Reengineering

To improve the diastereofacial selectivity of the azepinone/siloxydiene Diels–Alder cycloaddition, we envisioned the alternative siloxydiene 36 (Figure 7). Based on molecular modeling studies, we hypothesized that a sterically demanding bromine atom would restrict rotation and block the “back” face of the diene, thus favoring the desired facial approach of the dienophile from the “front” face. It was unclear, however, whether such reengineering of the diene would erode the excellent regio- and endo-selectivity observed previously.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional models of the original cyclopropane-containing siloxydiene 9 and bromine-containing siloxydiene 36 suggesting improved diastereofacial selectivity in Diels–Alder cycloaddition of 36. Dienes are shown in blue; bromine is shown as a green sphere; silyl groups are abbreviated as purple spheres for simplicity.

To test this hypothesis, siloxydiene 36 was prepared from Weinreb amide 19 (Figure 8). Silyl deprotection (TBAF) was followed by acid-catalyzed nucleophilic cyclopropane fragmentation of the resulting cyclopropyl carbinyl alcohol to provide bromide 37. This transformation proved to be nontrivial, as competing intramolecular trapping of the putative cyclopropylcarbinyl carbocation by the amide led to various side products. Ultimately, we found that treatment with HBr/AcOH in fluorobenzene promoted the desired fragmentation with mimimal side reactions and concomitant installation of the equatorial bromide. Siloxydiene 36 was then prepared through a two-step procedure (vinylmagnesium bromide, THF, then TBSOTf, KHMDS, −78 °C).26 The requisite N-ethyl azepinone dienophile 8b was synthesized from ε-caprolactone (cf. Figure 4).21 We were then in position to test whether the equatorial bromide in siloxydiene 36 would provide the desired facial control in the key Diels–Alder cycloaddition.

Figure 8.

Diastereoselective Diels–Alder cycloaddition of bromide-containing siloxydiene 36. a) TBAF, THF, 99%; b) HBr/AcOH, C6H5F, 0 °C, 63%; c) vinylmagnesium bromide, THF, 0 °C; d) TBSOTf, KHMDS, THF, −78 °C, 80% over 2 steps; e) 8b, SnCl4, 4 Å molecular sieves, CH3CN, 87%; f) Tf2NH, CH2Cl2, 46%; g) AgO2CCF3, CH2Cl2, 60%.

Extensive experimentation revealed that the Diels–Alder cycloaddition between siloxydiene 36 and dienophile 8b could be executed under SnCl4 catalysis to provide cycloadduct 38 as a single isomer with the desired stereochemical configuration, as confirmed by X-ray crystallography. All other Lewis acids tested gave lower yields or selectivities [e.g., Yb(OTf)3, Sc(OTf)3, ZnCl2]. The excellent stereoselectivity is thought to arise from effective blocking of the undesired “back” face by the bulky bromine atom, favoring dienophile approach from the desired “front” face (Figure 7). We then attempted Mannich-type N-acyliminium cyclization to install the C11–C17 bond as in Figure 5. However, while treatment of 38 with Tf2NH did effect the desired cyclization, isomerization of the exocyclic double bond also occurred (39). Attempted activation with Ag(TFA) resulted in skeletal rearrangement of the bicyclo[3.2.1] ring system (40), whose structure was assigned based on 2D NMR analysis.21

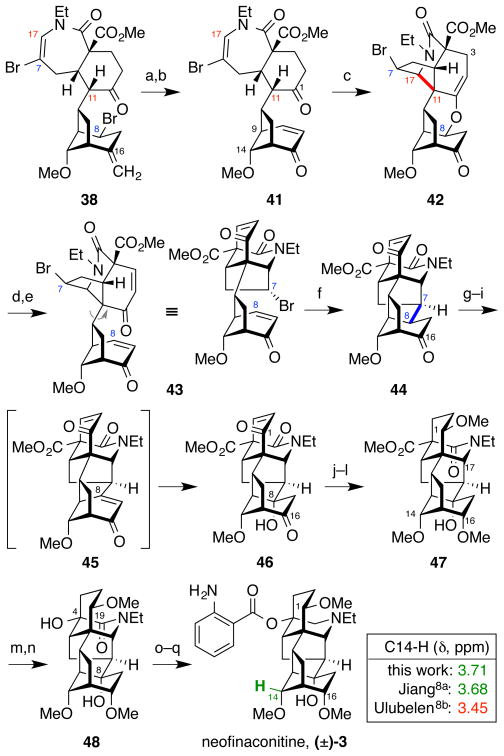

Completion of the Total Synthesis of Neofinaconitine

To overcome the above undesired reactions, we reasoned that an alternative enone substrate 41 (Figure 9) would allow the orchestration of the desired Mannich-type N-acyliminium cyclization by obviating the olefin migration in 39 and by precluding the skeletal rearrangement in 40 due to poor stereoelectronic overlap between the C9–C14 bond and the enone π-system. Thus, chemoselective oxidative cleavage of the C16 exocyclic olefin in 38 (OsO4, NMO then Pb(OAc)4) followed by bromine elimination with DBU provided enone 41. As predicted, treatment of 41 with Tf2NH then provided the desired cyclization product 42, presumably via acid-catalyzed conjugate addition of the C1 ketone oxygen into the enone, followed by Mannich-type N-acyliminium cyclization to furnish the C11–C17 bond.

Figure 9.

Completion of the total synthesis of neofinaconitine via C11–C17 Mannich-type N-acyliminium cyclization and C7–C8 radical cyclization; diagnostic 1H-NMR peaks for neofinaconitine11a and delphicrispuline11b (CDCl3). a) OsO4, NMO, THF, H2O, then Pb(OAc)4, 65%; b) DBU, toluene, 87%; c) Tf2NH, CH2Cl2, 75%; d) CAN, CH3CN, H2O, 60 °C; e) MsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 50 °C, 66% over 2 steps; f) Bu3SnH, AIBN, PhH, 80 °C, 99%; g) TMSOTf, Et3N, THF, 0 °C; h) PhSeCl, CH2Cl2, 0 °C 86% over 2 steps; i) NaIO4, THF, H2O, 59%; j) Pd/C, H2, EtOAc; k) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C, 89% over 2 steps; l) MeI, t-BuOK, THF, 0 °C, 34%; m) LiBH4, THF; n) CrO3, 0.5 N H2SO4, 40% over 2 steps; o) LiAlH4, THF, 85 °C; p) o-NO2BzCl, DMAP, Et3N, C6H6, 80 °C; q) Zn, HCl, MeOH, H2O, 13% over 3 steps.

Construction of the aconitine skeleton was then completed via a series of transformations similar to those in Figure 6. Allylic oxidation at C3 of enol ether 42 (CAN)31 followed by activation of the resulting allylic alcohol as the mesylate with ensuing elimination (MsCl, Et3N) provided bis-enone 43. Conjugate addition of the radical generated from the secondary C7 bromide (Bu3SnH, AIBN) into the enone at C8 then afforded the hexacyclic skeleton 44. Installation of the C8-hydroxyl was achieved by a 3-step sequence involving silylenolation of the C16 ketone (TMSOTf, Et3N), α-selenylation (PhSeCl), and selenoxide elimination with concomitant chemoselective conjugate addition of water at C8 of the putative highly strained bridgehead olefin intermediate 45 (NaIO4) to afford the tertiary alcohol 46.

The C1 enone in 46 was then transformed into a C1 methyl ether in 47 by enone hydrogenation (H2, Pd/C), NaBH4 reduction of both the C1 and C16 ketones, and selective methylation of the C1 and C16 secondary alcohols in the presence of the C8 tertiary alcohol (MeI, t-BuOK). The remainder of the material consisted of a mixture of C1-O and C16-O monomethylated products. An alternative, improved approach involving selective demethylation of a tris(methyl ether) was developed subsequently (vide infra). Notably, the NaBH4 reduction step gave a single diastereomer, with two newly generated stereocenters at C1 and C16. Although the stereochemical configurations at C1 and C16 remained formally unassigned at this stage, axial attack by borohydride was presumed and the material was carried forward for later verification of the configurations at these centers.

The endgame was then advanced by one-carbon oxidative truncation of the C4 methyl ester in 47 to the tertiary alcohol in 48 (LiBH4 then CrO3).32 Amide reduction at C19 in 48 (LiAlH4) then revealed the requisite tertiary amine. The remaining formidable task was selective acylation of the C4 tertiary alcohol in the presence of the C8 tertiary alcohol. The scarcity of literature precedents for such a hindered acylation with anthranilic acid33 prompted us to develop a 2-step procedure via the corresponding o-nitrobenzoate (o-NO2BzCl, then Zn, HCl) to provide racemic neofinaconitine, (±)-3. The observed site selectivity for C4 presumably arises from steric shielding of the C8 alcohol by the C14- and C16-methoxy groups.

The 1H-NMR spectrum of this synthetic material was consistent with the reported spectral data for neofinaconitine.11a,21 Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain an authentic sample for direct comparison, and efforts to prepare an X-ray quality crystal with this material were unsuccessful.

Relay Synthesis of Neofinaconitine and 9-Deoxy-lappaconitine from Condelphine and Structural Confirmation

Although the spectral agreement above confirmed that our synthetic material was identical to the natural product, the lack of stereochemical confirmation at C1 and C16 in our total synthesis and the spectral discrepancy between neofinaconitine and delphicrispuline11 at the C14 proton prompted us to develop a relay synthesis of neofinaconitine starting from a commercially available aconitine alkaloid that provided well-established stereochemistry and bond connectivity. Convergence of spectral data for the relay synthetic material, our fully synthetic material, and the natural product would then further corroborate the assigned structure of neofinaconitine.

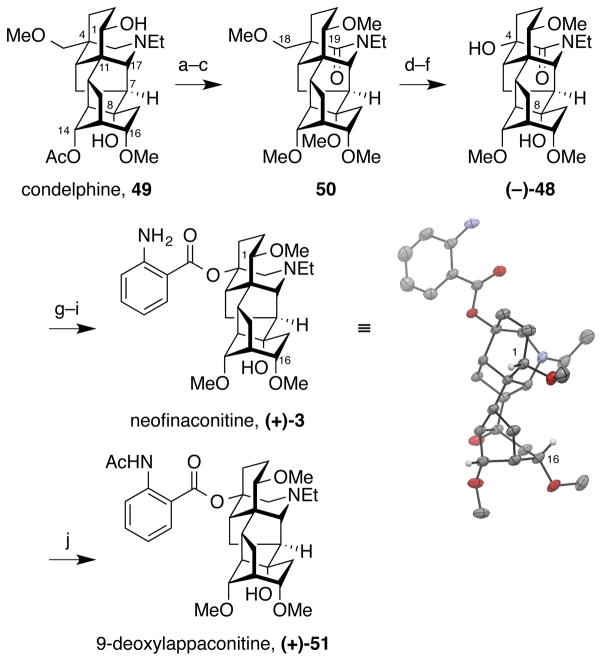

After careful evaluation of commercially available alkaloids from the aconitine family, condelphine (49) was chosen as the starting point for relay synthesis, since it possesses all the required substitutions and stereochemistry at C1, C8, C14 and C16 (Figure 10). However, a method needed to be developed for truncation of the C4-methoxymethyl group to the requisite C4-hydroxyl.

Figure 10.

Relay synthesis of neofinaconitine and 9-deoxylappaconitine from condelphine. a) NaOH, H2O, EtOH. b) NaH, MeI, THF, 100 °C; c) KMnO4, H2O, CH2Cl2, 54% over 3 steps; d) BBr3·SMe2, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; e) CrO3, 0.5 N H2SO4; f) 0.5 N H2SO4, 80 °C, 46% over 3 steps; g) LiAlH4, THF, 80 °C; h) o-NO2BzCl, DMAP, Et3N, C6H6, 80 °C; i) Zn, HCl, MeOH, H2O, 70% over 3 steps; j) Ac2O, pyridine, 91%.

The relay synthesis began with basic hydrolysis of the C14 acetate of condelphine, 49, (aq NaOH),34 followed by permethylation (NaH, MeI) to give a pentamethyl ether that was subjected directly to KMnO4 oxidation of the tertiary amine to afford C19 amide 50.32 This seemingly superfluous C19-oxidation served two vital purposes. First, it enabled selective demethylation of the C18-methoxy group (BBr3), presumably due to boron precoordination to the C19 carbonyl enabling selective activation of C18 oxygen. Second, it promoted oxidative cleavage of the C18 alcohol (CrO3) to deliver the requisite C4 tertiary alcohol (−)-48, in which the C8-methoxy group had also been cleaved (H2SO4, 80 °C). This formal C8-O-demethylation may proceed through the intermediacy of C8 tertiary carbocation, which is trapped with water. Finally, (−)-48 was advanced to enantiomerically pure neofinaconitine, (+)-3, as in the total synthesis route (cf. Figure 9).

The spectroscopic data of the relay synthetic neofinaconitine matched those of the total synthesis material, confirming the identity of the latter and the stereochemical configurations at C1 and C16. In addition, acetylation of neofinaconitine (Ac2O, pyridine) afforded 9-deoxylappaconitine, (+)-51, the spectral data of which was also consistent with literature data.11a,21 Further, X-ray crystallographic analysis of the relay synthetic neofinaconitine provided unambiguous confirmation of the structure of the relay synthetic material and, by extension, the structures of the fully synthetic and natural neofinaconitine. Variation of concentration did not modulate the 1H-NMR chemical shift of the C14 proton and addition of 1 equiv HCl resulted in precipitation from CDCl3. Accordingly, because of the significant discrepancy in the reported chemical shift of the C14 proton of delphicrispuline (Figure 9), its structural assignment as identical to neofinaconitine merits reevaluation.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a novel, modular, and convergent synthetic strategy toward the norditerpenoid alkaloids has been developed, culminating in the first total synthesis of neofinaconitine. An unusual Diels–Alder cycloaddition between the unstable cyclopentadiene 10 and cyclopropene 11 proved successful with no scrambling of cyclopentadiene substituents observed. Azepinones 8 were also established as a competent Diels–Alder dienophiles that allowed rapid construction of the [5.4.0]-bicycloazepine ring system in the key cyclization precursors 7 and 38. Although the Mannich-type N-acyliminium cyclization of 24 afforded a cyclic enol ether 29 that proved recalcitrant to hydrolysis, this obstacle was overcome using an oxidative elimination approach (30 → 32). The poor diastereoselectivity of the key azepinone/siloxydiene Diels–Alder cycloaddition was improved by substrate reengineering with a sterically demanding bromine substituent. Moreover, a concise, 10-step relay synthesis of neofinaconitine and 9-deoxylappaconitine from condelphine was developed, confirming the structure of the neofinaconitine natural product by x-ray crystallographic analysis. Determination of the true structure of delphicrispuline will require further studies. Synthetic access to neofinaconitine analogues will enable full biological evaluation and elucidation of mechanisms of ion channel modulation by the norditerpenoid alkaloids.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to the memory of our colleague and mentor, Prof. David Y. Gin (1967–2011). We thank Prof. Samuel Danishefsky (MSKCC) for critical reading of this manuscript, Dr. George Sukenick, Dr. Hui Liu, Hui Fang, and Dr. Sylvia Rusli (MSKCC Analytical Core Facility) for expert NMR and mass spectral support and Dr. Aaron Sattler and Prof. Gerard Parkin (Columbia University) and Dr. Louis Todaro (Hunter College) for X-ray crystallographic analyses. Financial support from the NIH (GM067659 to D.Y.G.) and The Carlsberg Foundation (postdoctoral fellowship to L.U.N.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Complete experimental procedures and analytical data for key new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.(a) Amiya T, Bando H. Aconitum Alkaloids. In: Brossi A, editor. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. Vol. 34. Academic Press; San Diego: 1988. pp. 95–179. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang F-P, Chen Q-H. The C19-Diterpenoid Alkaloids. In: Cordell GA, editor. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 69. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2010. p. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang F-P, Chen Q-H, Liang X-T. The C18-Diterpene Alkaloids. In: Cordell GA, editor. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology. Vol. 67. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2009. p. 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang TK. Handbook of Composition and Pharmacological Action of Commonly-used Traditional Chinese Medicine. Yi-Yao Science & Technology Press; Beijing: 1994. pp. 923–926.pp. 1367–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang FP, Chen QH, Liu XY. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:529–570. doi: 10.1039/b916679c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Schmidt E, Schulze H. Arch Pharm. 1906;244:136–159. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schulze H, Ulfert F. Arch Pharm. 1922;260:230–243. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Wiesner K, Götz M, Simmons DL, Fowler LR, Bachelor FW, Brown RFC, Büchi G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1959;1(2):15–24. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wiesner K, Bickelhaput F, Babin DR, Götz M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1959;1(3):11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ameri A. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:211–235. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadikov AZ, Shakirov TT. Khim Prir Soedin. 1988;24:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Synthesis: Wiesner K, Tsai TYR, Huber K, Bolton SE, Vlahov R. J Am Chem Soc. 1974;96:4990–4992.Structure determination: Khaimova MA, Palamereva MD, Mollov NM, Krestev VP. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:819–822.

- 8.(a) Tsai TYR, Tsai CSJ, Sy WW, Shanbhag MN, Liu WC, Lee SF, Wiesner K. Heterocycles. 1977;7:217–226. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wiesner K, Tsai TYR, Nambiar KP. Can J Chem. 1978;56:1451–1454. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee SF, Sathe GM, Wy WW, Ho PT, Wiesner K. Can J Chem. 1976;54:1039–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Wiesner K. Pure Appl Chem. 1979;51:689–703. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wiesner K. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:485–497. [Google Scholar]

- 10.For selected model studies: Shishido K, Hiroya K, Fukumoto K, Tetsuji K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:1167–1170.Taber DF, Liang JL, Chen B, Cai L. J Org Chem. 2005;70:8739–8742. doi: 10.1021/jo051155y.Conrad RM, Du Bois J. Org Lett. 2007;9:5465–5468. doi: 10.1021/ol702375r.Yang ZK, Chen QH, Wang FP. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:4192–4195.

- 11.Neofinaconitine: Jiang S, Hong S, Song B, Zhu Y, Zhou B. Acta Chimica Sinica. 1988;46:26–29.Delphicrispuline: Ulubelen A, Meriςli AH, Meriςli F, Kolak U, Ilarslan R, Voelter W. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:513–516.

- 12.Diels O, Alder K. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1928;460:98–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Wiberg KB, Bartley WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:6375–6380. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kagi RI, Johnson BL. Aust J Chem. 1975;28:2175–2187. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLean S, Haynes P. Tetrahedron. 1965;21:2329–2342. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudon J, Cernak TA, Ashenhurst JA, Gleason JL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8885–8888. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Jones DW. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1980:739–740. [Google Scholar]; (b) McClinton MA, Sic V. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1992:1891–1895. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wellman MA, Burry LC, Letourneau JE, Bridson JN, Miller DO, Burnell DJ. J Org Chem. 1997;62:939–946. doi: 10.1021/jo9707949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Dulayymi AR, Al Dulayymi JR, Baird MS, Gerrard ME, Koza G, Harkins SD, Roberts E. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:3409–3424. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran TT, Hay DA, Koegel CP, Evans JC. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:1983–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forsyth CJ, Clardy J. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:3497–3505. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regiochemistry in 17 was assigned by COSY analysis of the subsequent ketone 18, while stereochemical configurations were assigned based on 1D-NOE analysis of the subsequent Weinreb amide 19.

- 21.See Supporting Information for complete details.

- 22.Diels–Alder cycloaddition of 2,5-bis(t-butyldimethylsiloxy)-cyclopentadiene with cyclopropene 11 also favored contrasteric approach (≥10:1). In contrast, reaction with benzophenone as the dienophile proceeded almost exclusively from the sterically less-hindered face of this diene (1:15).

- 23.Wadsworth W, Emmons WD. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:1733–1738. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Levin JI, Turos E, Weinreb SM. Synth Commun. 1982;12:989–993. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nahm S, Weinreb SM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:3815–3818. [Google Scholar]; (c) Luke GP, Morris J. J Org Chem. 1995;60:3013–3019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiyamizu H, Ooi H, Inomoto Y, Esumi T, Iwabuchi Y, Hatakeyama S. Org Lett. 2001;3:473–475. doi: 10.1021/ol006982u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou G, Hu Q, Corey EJ. Org Lett. 2003;5:3979–3982. doi: 10.1021/ol035542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marzorati M, Hult K, Riva S, Danieli B. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:1963–1968. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh JR, Doering WVE. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:5505–5507. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grieco PA, Miyashita M. J Org Chem. 1974;39:120–122. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicolaou KC, Adsool VA, Hale CRH. Org Lett. 2010;12:1552–1555. doi: 10.1021/ol100290a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.For selected examples, see: Renzo R, Yuji N, Manfred S. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:4603–4610.Breytenbach JC, Zyl JJ, Merwe PJ, Rall GJH, Roux DG. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 1981:2684–2691.

- 32.Abdelrahman D, Benn M, Hellyer R, Parvez M, Edwards OE. Can J Chem. 2006;84:1167–1173. [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Schepartz A, Breslow R. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1814–1826. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barker D, Brimble MA, McLeod MD. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:5953–5963. [Google Scholar]; (c) DiBiase G. J Org Chem. 1978;43:447–452. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanuman JB, Katz A. Phytochemistry. 1994;35:1527–1543. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.