Abstract

Background

Recent studies have shown that the presence of systemic inflammation correlates with poor survival in various types of cancers. This study investigated the usefulness of a novel inflammation-based prognostic system, using the combination of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR), collectively named the CNP, for predicting survival in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).

Materials and methods

The CNP was calculated on the basis of data obtained on the day of admission: patients with both elevated NLR (>3.45) and PLR (>166.5) were allocated a score of 2, and patients showing one or neither were allocated a score of 1 or 0, respectively.

Results

The CNP was associated with tumor length (P<0.001), differentiation (P=0.021), depth of invasion (P<0.001), and nodal metastasis (P<0.001). No significant differences were found between the CNP and morbidity. However, significant differences were found between the CNP and mortality (P,0.001). The overall survival in the CNP 0, CNP 1, and CNP 2 groups were 63.4%, 50.0%, and 20.2%, respectively (CNP 0 versus CNP 1, P=0.014; CNP 1 versus CNP 2, P<0.001). Multivariate analyses showed that CNP was a significant predictor of overall survival. CNP 1–2 had a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.964 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.371–2.814, P<0.001) for overall survival. CNP (HR =1.964, P<0.001) is superior to NLR (HR =1.310, P=0.053) or PLR (HR =1.751, P<0.001) as a predictive factor.

Conclusion

The CNP is considered a useful predictor of postoperative survival in patients with ESCC. The CNP is superior to NLR or PLR as a predictive factor in patients with ESCC.

Keywords: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), neutrophil lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet lymphocyte ratio (PLR), overall survival

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is the eighth most common type of cancer worldwide.1 In the People’s Republic of China, EC is the fourth most common cause of mortality and is frequently located in the thorax, while 95% of EC is pathologically diagnosed as esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).2 Although advances have occurred in multidisciplinary treatment, surgical resection remains the modality of choice. The postoperative overall survival is poor, the reason for which is the relatively late stage of diagnosis and rapid clinical progression.3,4 Therefore, assessing prognostic factors in patients with EC will become more and more important.

Recently, there is increasing evidence that a systemic inflammatory response (SIR) is associated with postoperative survival in patients with various cancers.5,6 C-reactive protein (CRP) is one index of systemic inflammation. The significance of pretreatment serum levels of CRP as a parameter of the perioperative course and long-term prognosis in EC has been investigated.7–9 The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) are other markers, and their prognostic values have been shown in several types of cancer, including EC.10–13 In the present study, therefore, we initially evaluated the usefulness of a novel inflammation-based prognostic system, named the CNP (the combination of NLR and PLR), for predicting the survival of patients with ESCC.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 1048 patients who underwent esophagectomy for EC at the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China) from January 2005 to December 2008 were eligible for this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) ESCC confirmed by histopathology; 2) surgery with curative esophagectomy; 3) at least six lymph nodes were examined for pathological diagnosis; 4) surgery was neither preceded nor followed by chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy; and 5) preoperative NLR and PLR were obtained before esophagectomy within 1-week. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) non-ESCC or gastroesophageal junction carcinoma; 2) previous or concomitant other cancer; 3) previous or concomitant esophagectomy for benign disease; 4) incomplete resection with microscopic or macroscopic residual tumors; 5) previous chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy; 6) previous anti-inflammatory medicines within 1-week; or 7) distant metastatic disease. Ultimately, 483 patients were included in this study. All subjects gave written informed consent to the study protocol, which was approved by the Ethical Committees of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, Hangzhou, People’s Republic of China.

Surgery

All patients were treated with radical resection. Four surgeons were involved in our study. The standard surgical approach consisted of a limited thoracotomy on the right side and intrathoracic gastric reconstruction for lesions at the middle/lower third of the esophagus. Upper third lesions were treated by cervical anastomosis.2 In our institute, the majority of patients underwent two-field lymphadenectomy. In this cohort of patients, thoracoabdominal lymphadenectomy was performed, including the subcarinal, paraesophageal, pulmonary ligament, diaphragmatic, and paracardial lymph nodes, as well as those located along the lesser gastric curvature, the origin of the left gastric artery, the celiac trunk, the common hepatic artery, and the splenic artery. Three-field lymphadenectomy was performed only if the cervical lymph nodes were thought to be abnormal upon preoperative evaluation.

Pathological analysis

Fresh specimens were routinely dissected and measured by surgeons immediately after resection of the tumor. The length of each tumor was measured with a handheld ruler and was recorded in the operation notes. Then the specimens were sent for pathology examination after preservation in 10% formalin. The differentiation, vessel involvement, perineural invasion, depth of invasion, and nodal metastasis were recorded according to the results of pathologic reports. All patients were staged according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual.14

Follow-up

In our institute, patients were followed up at our outpatient department every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years after resection, then annually. Recording of medical history, physical examination, and computed tomography of the chest were performed during the follow-up. Endoscopy was obtained in cases of clinically indicated recurrence or metastasis. The last follow-up was 30 November 2011.

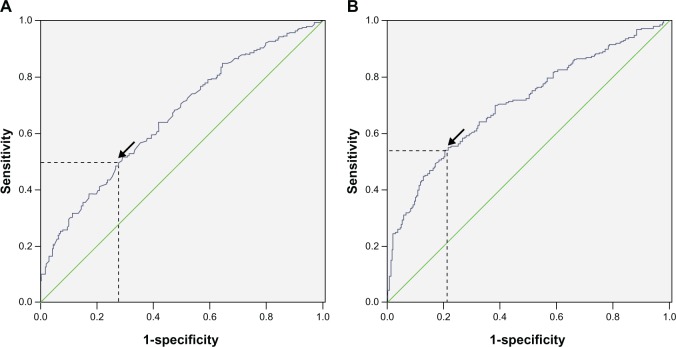

CNP evaluation

Data on preoperative blood cell counts were extracted in a retrospective fashion from the medical records. All white blood cell and differential counts were taken within 1-week prior to surgery. The NLR was defined as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count and PLR was defined as the absolute platelet count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for overall survival prediction were plotted to verify the optimum cut-off point for NLR and PLR. The recommended cut-off values for NLR and PLR were 3.45 and 166.5, respectively (Figure 1). The CNP was calculated on the basis of data obtained on the day of admission: patients with both an elevated NLR (>3.45) and PLR (>166.5) were allocated a score of 2, and patients showing one or neither were allocated a score of 1 or 0, respectively.

Figure 1.

ROC for NLR (A) and PLR (B).

Notes: A ROC curve plots the sensitivity on the y-axis against 1-specificity on the x-axis. A diagonal line at 45 degrees, known as the line of chance, would result from a test which allocated subjects randomly. Each point on the ROC curve corresponds to a value of platelet count. In general, a good cut-off point is one that produces both a large sensitivity and a large specificity. This can be interpreted as choosing the point on the ROC curve with the largest vertical distance from the line of chance. ROC curves for overall survival prediction were plotted to verify the optimum cut-off point for NLR and PLR, which was 3.45 and 166.5, respectively (arrows). (A) The area under the ROC curve for NLR was 65.8% with a sensitivity of 49.6% and a specificity of 72.8%. (B) The area under the ROC curve for PLR was 70.8% with a sensitivity of 54.1% and a specificity of 79.5%.

Abbreviations: NIR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet lymphocyte ratio; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The overall cumulative probability of survival was calculated using the Kaplan– Meier method, and the difference was assessed by the log-rank test. A univariate analysis was used to examine the association between various prognostic predictors and survival. Possible prognostic factors associated with overall survival were considered in a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to quantify the strength of the association between predictors and survival. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

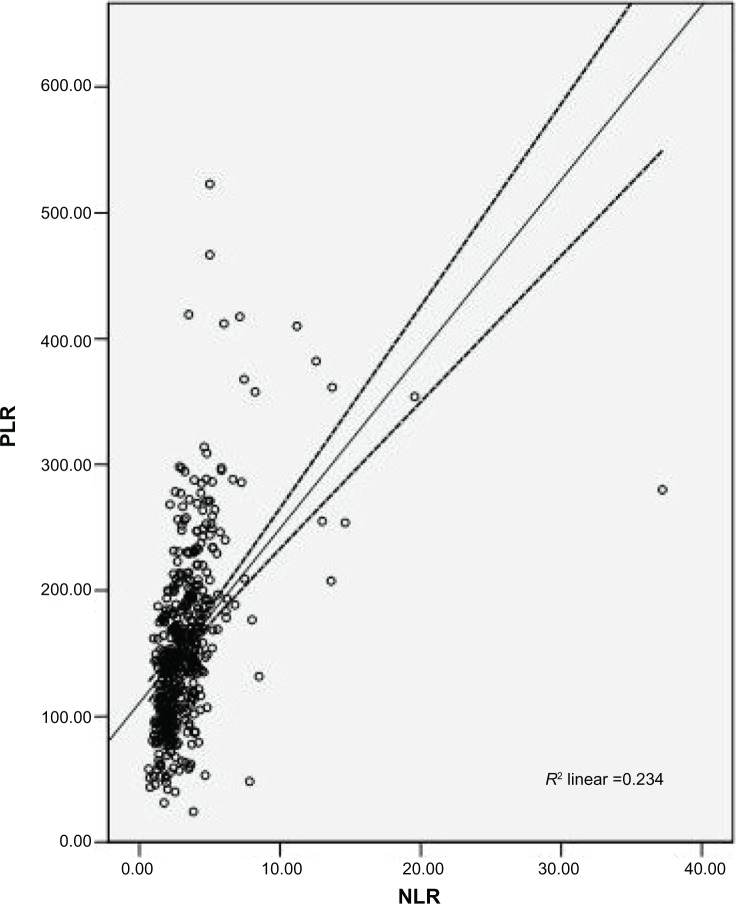

Among the 483 patients with ESCC, 72 (14.9%) were women and 411 (85.1%) were men. The mean age was 59.1±8.0 years, with an age range of 34–80 years. The relationships between CNP and clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Table 1. Our study showed that CNP was associated with tumor length (P<0.001), differentiation (P=0.021), depth of invasion (P<0.001), and nodal metastasis (P<0.001). No significant differences were found between the CNP and morbidity. However, significant differences were found between the CNP and mortality (P<0.001). In addition, there was a positive correlation between NLR and PLR (r=0.483, P<0.001; Figure 2).

Table 1.

The relationships between CNP and clinicopathological characteristics

| Cases (n, %) | CNP 0 (n, %) | CNP 1 (n, %) | CNP 2 (n, %) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.563 | ||||

| ≤60 | 273 (56.5) | 128 (54.5) | 76 (56.7) | 69 (60.5) | |

| >60 | 210 (43.5) | 107 (45.5) | 58 (43.3) | 45 (39.5) | |

| Gender | 0.167 | ||||

| Female | 72 (14.9) | 42 (17.9) | 18 (13.4) | 12 (10.5) | |

| Male | 411 (85.1) | 193 (82.1) | 116 (86.6) | 102 (89.5) | |

| Tumor length (cm) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤3 | 138 (28.6) | 99 (42.1) | 24 (17.9) | 15 (13.2) | |

| >3 | 345 (71.4) | 136 (57.9) | 110 (82.1) | 99 (86.8) | |

| Tumor location | 0.981 | ||||

| Upper | 27 (5.6) | 12 (5.1) | 8 (6.0) | 7 (6.1) | |

| Middle | 247 (51.1) | 120 (51.1) | 67 (50.0) | 60 (52.6) | |

| Lower | 209 (43.3) | 103 (43.8) | 59 (44.0) | 47 (41.3) | |

| Vessel involvement | 0.380 | ||||

| Negative | 407 (84.3) | 203 (86.4) | 112 (83.6) | 92 (80.7) | |

| Positive | 76 (15.7) | 32 (13.6) | 22 (16.4) | 22 (19.3) | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.060 | ||||

| Negative | 390 (80.7) | 196 (83.4) | 99 (73.9) | 95 (83.3) | |

| Positive | 93 (19.3) | 39 (16.6) | 35 (26.1) | 19 (16.7) | |

| Differentiation | 0.021 | ||||

| Well | 71 (14.7) | 32 (13.6) | 21 (15.7) | 18 (15.8) | |

| Moderate | 323 (66.9) | 170 (72.3) | 89 (66.4) | 64 (56.1) | |

| Poor | 89 (18.4) | 33 (14.1) | 24 (17.9) | 32 (28.1) | |

| Depth of invasion | <0.001 | ||||

| T1 | 87 (18.0) | 69 (29.4) | 13 (9.7) | 5 (4.4) | |

| T2 | 80 (16.6) | 41 (17.4) | 21 (15.7) | 18 (15.8) | |

| T3 | 265 (54.9) | 111 (47.2) | 83 (61.9) | 71 (62.3) | |

| T4 | 51 (10.5) | 14 (6.0) | 17 (12.7) | 20 (17.5) | |

| Nodal metastasis | <0.001 | ||||

| Negative | 274 (56.7) | 162 (68.9) | 65 (48.5) | 47 (41.2) | |

| Positive | 209 (43.3) | 73 (31.1) | 69 (51.5) | 67 (58.8) | |

| Morbidity | |||||

| Pneumonia | 53 (11.0) | 31 (13.2) | 11 (8.2) | 11 (9.6) | 0.296 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 65 (13.5) | 36 (15.3) | 15 (11.1) | 14 (12.3) | 0.491 |

| Mortality | 244 (50.5) | 86 (36.6) | 67 (50.0) | 91 (79.8) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CNP, the combination of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio; T, tumor.

Figure 2.

Correlation between NLR and PLR.

Note: There was a positive correlation between NLR and PLR (r=0.483, P<0.001).

Abbreviations: NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet lymphocyte ratio.

Prognostic factors

Univariate analyses showed that tumor length, vessel involvement, perineural invasion, differentiation, depth of invasion, nodal metastasis, NLR, PLR, and CNP were predictive of survival (Table 2). Multivariate analyses were performed with the Cox proportional hazards model. In that model, we demonstrated that differentiation (P=0.010), depth of invasion (P=0.039), nodal metastasis (P<0.001), PLR (P<0.001), and CNP (P<0.001) were independent prognostic factors (Table 3). However, the results of our study showed that CNP (HR =1.964, P<0.001) is superior to NLR (HR =1.310, P=0.053) or PLR (HR =1.751, P<0.001) as a predictive factor in patients with ESCC.

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of overall survival in ESCC patients

| OS (%) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.780 | ||

| ≤60 | 49.5 | 1.000 | |

| >60 | 49.5 | 1.075 (0.647–1.785) | |

| Sex | 0.071 | ||

| Female | 61.1 | 1.000 | |

| Male | 47.4 | 1.437 (0.969–2.131) | |

| Tumor location | 0.069 | ||

| Upper/middle | 53.6 | 1.000 | |

| Lower | 44.0 | 1.262 (0.982–1.623) | |

| Tumor length (cm) | <0.001 | ||

| ≤3 | 66.7 | 1.000 | |

| >3 | 42.6 | 2.158 (1.564–2.977) | |

| Vessel involvement | 0.001 | ||

| Negative | 52.6 | 1.000 | |

| Positive | 32.9 | 1.673 (1.228–2.279) | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.028 | ||

| Negative | 51.8 | 1.000 | |

| Positive | 39.8 | 1.397 (1.036–1.884) | |

| Differentiation | 0.008 | ||

| Well/moderate | 51.9 | 1.000 | |

| Poor | 38.6 | 1.507 (1.114–2.040) | |

| Depth of invasion | <0.001 | ||

| T1–2 | 68.0 | 1.000 | |

| T3–4 | 39.5 | 2.363 (1.746–3.199) | |

| Nodal metastasis | <0.001 | ||

| Negative | 65.0 | 1.000 | |

| Positive | 29.2 | 2.795 (2.158–3.621) | |

| NLR | <0.001 | ||

| ≤3.45 | 57.9 | 1.000 | |

| >3.45 | 35.4 | 1.950 (1.516–2.508) | |

| PLR | ,0.001 | ||

| ≤166.5 | 61.1 | 1.000 | |

| >166.5 | 30.2 | 2.195 (1.706–2.824) | |

| CNP | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 63.4 | 1.000 | |

| 1 | 50.0 | 1.483 (1.077–2.041) | |

| 2 | 20.2 | 3.186 (2.369–4.286) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CNP, the combination of NLR and PLR; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet lymphocyte ratio; OS, overall survival; T, tumor.

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of overall survival in ESCC patients

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor length (>3 cm versus ≤3 cm) | 1.170 (0.806–1.699) | 0.409 |

| Vessel involvement (positive versus negative) | 1.064 (0.771–1.469) | 0.706 |

| Perineural invasion (positive versus negative) | 1.127 (0.827–1.537) | 0.449 |

| Differentiation (poor versus well/moderate) | 1.528 (1.119–2.085) | 0.008 |

| Depth of invasion (T3–4 versus T1–2) | 1.502 (1.046–2.156) | 0.028 |

| Nodal metastasis (positive versus negative) | 2.127 (1.605–2.819) | <0.001 |

| NLR (>3.45 versus ≤3.45) | 1.310 (0.997–1.722) | 0.053 |

| PLR (>166.5 versus ≤166.5) | 1.751 (1.345–2.280) | <0.001 |

| CNP (1–2 versus 0) | 1.964 (1.371–2.814) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CNP, the combination of NLR and PLR; ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; NLR, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet lymphocyte ratio; T, tumor.

Overall survival

The overall survival of CNP 0, CNP 1, and CNP 2 patients were 63.4%, 50.0%, and 20.2%, respectively (CNP 0 versus CNP 1, P=0.014; CNP 1 versus CNP 2, P<0.001; Figure 3). Thus, CNP was able to clearly classify patients into three independent groups.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves stratified by CNP.

Notes: The overall survival of CNP 0, CNP 1, and CNP 2 patients were 63.4%, 50.0%, and 20.2%, respectively (CNP 0 versus CNP 1, P=0.014; CNP 1 versus CNP 2, P<0.001). Thus, CNP was able to clearly classify such patients into three independent groups.

Abbreviations: Cum, cumulative; CNP, the combination of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio; m, minutes.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the prognostic value of CNP (the combination of NLR and PLR) for predicting prognosis for patients with ESCC. Our study showed that CNP is associated with tumor progression and can be considered as an independent marker of poor prognosis in patients who underwent esophagectomy for ESCC without neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment.

There is strong linkage between inflammation and cancer. Systemic chemotherapy or radiation will inevitably have an impact on the systemic inflammation. Thus, evaluation of CNP in neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemoradio therapy does not reflect the baseline impact of systemic inflammation on clinical outcome in EC patients. Thus, in our study, we evaluated the potential prognostic role of preoperative CNP in patients undergoing esophagectomy for ESCC without neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment.

With the increasing evidence that host or immune responses are important prognostic indicators, a variety of prognostic scores based on the presence of an SIR have been described.15 Cancer-related inflammation causes suppression of antitumor immunity by recruiting regulatory T cells and activating chemokines, which results in tumor growth and metastasis.16 The mechanism between cancer and neutrophilia and leukocytosis remains unclear; however, cancer has been shown to produce granulocyte colony stimulating factor, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6, which may influence tumor-related leukocytosis and neutrophilia.17,18

Preoperative NLR is inversely related to prognosis in many cancers, however, its role in EC is still controversial. Sato et al11 and Sharaiha et al12 demonstrated that a high NLR is associated with tumor progression and poor survival in patients with EC. However, Dutta et al19 and Rashid et al13 showed that NLR does not correlate with prognostic factors in EC. PLR is an additional index of systemic inflammation elicited by the tumor. However, there have been few studies regarding PLR in patients with EC. Dutta et al19 showed that PLR does not correlate with prognostic factor in patients with EC. In the present study, therefore, we initially evaluated the usefulness of CNP for predicting the postoperative survival in patients with ESCC. Furthermore, controversy exists concerning the optimal cut-off points for NLR and PLR to predict overall survival. In our study, therefore, ROC curves for overall survival prediction were plotted to verify the optimum cut-off point for NLR and PLR, which were 3.45 and 166.5, respectively. In our study, Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that the CNP was able to divide such patients into three independent groups (P<0.001). Multivariate analyses showed that CNP was a significant predictor of overall survival. CNP 1–2 had an HR of 1.964 (95% CI: 1.371–2.814, P<0.001) for overall survival.

The tumor-associated inflammatory cell infiltrate is recognized to have prognostic value in various common solid tumors, including breast, colorectal, and ovarian cancers.20–22 Klintrup et al23 simplified the subjective measurement of the tumor inflammatory infiltrate for routine pathology reporting by including all white blood cell types and classifying the inflammatory cell infiltrate as either lowgrade or highgrade, which is known as the Klintrup–Makinen criteria. They reported that a high-grade tumor inflammatory cell infiltrate was associated with improved survival in patients undergoing curative resection of node-negative colorectal cancer. However, whether inflammatory cell infiltration around the tumor was associated with inflammatory cells has not been established. Jamieson et al24 showed that a highgrade inflammatory cell infiltrate was inversely associated with the magnitude of the Glasgow prognostic score (GPS). Ohashi et al25 showed that patients without nodal metastasis had more frequent tumor-associated eosinophil and neutrophil infiltration than those with nodal metastasis.

There are now a number of well-established systemic inflammation-based prognostic scores for patients with EC. In particular, the GPS has been well validated. Several previous studies have demonstrated that GPS (the combination of an elevated CRP and hypoalbuminemia) is associated with poor survival in various cancers, including EC.26,27 However, determining which of CNP or GPS is more useful to predict prognosis was impossible in this study as preoperative CRP was not always examined in our institute. Thus, we have added NLR and PLR in univariate and multivariate analyses. The results of our study showed that CNP (HR =1.964, P<0.001) was superior to NLR (HR =1.310, P=0.053) or PLR (HR =1.751, P<0.001) as a predictive factor in patients with ESCC. Furthermore, CNP is easy to measure routinely because of its low cost and convenience. Thus, CNP should be considered as an alternative to GPS.

The potential limitations of the present study include the use of a retrospective analysis and the short duration of the mean follow-up duration, and the fact that the study was conducted by a single institution. In addition, because the study used data from a single institution but with different pathologists and different surgeons, there may have been a lack of uniformity in the data. Furthermore, we excluded patients who had adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, which may have influenced our analysis. Thus, larger prospective studies will need to be performed to confirm these preliminary results.

In conclusion, our study showed that CNP is associated with tumor progression and can be considered as an independent marker of prognosis in patients who underwent esophagectomy for ESCC without neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment. Therefore, CNP not only appears capable of classifying patients with ESCC into three independent groups before surgery but also has potential as a novel predictor of postoperative survival in such patients. However, larger prospective studies will need to be performed to confirm these preliminary results.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feng JF, Huang Y, Zhao Q. Tumor length in elderly patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: is it a prognostic factor? Ups J Med Sci. 2013;118(3):145–152. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2013.792887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tachibana M, Kinugasa S, Hirahara N, Yoshimura H. Lymph node classification of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(2):427–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng JF, Zhao Q, Chen QX. Prognostic value of subcarinal lymph node metastasis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(5):3183–3186. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.5.3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454(7203):436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357(9255):539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zingg U, Forberger J, Rajcic B, Langton C, Jamieson GG. Association of C-reactive protein levels and long-term survival after neoadjuvant therapy and esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(3):462–469. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nozoe T, Saeki H, Sugimachi K. Significance of preoperative elevation of serum C-reactive protein as an indicator of prognosis in esophageal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;182(2):197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada H, Nabeya Y, Okazumi S, et al. Elevation of preoperative serum C-reactive protein level is related to poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83(4):248–252. doi: 10.1002/jso.10275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang D, Yang JX, Cao DY, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as independent predictors of cervical stromal involvement in surgically treated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:211–216. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S41711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato H, Tsubosa Y, Kawano T. Correlation between the pretherapeutic neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and the pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36(3):617–622. doi: 10.1007/s00268-011-1411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharaiha RZ, Halazun KJ, Mirza F, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of postoperative disease recurrence in esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(12):3362–3369. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1754-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rashid F, Waraich N, Bhatti I, et al. A pre-operative elevated neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio does not predict survival from oesophageal cancer resection. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice TW, Rusch VW, Ishwaran H, Blackstone EH, Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration Cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: data-driven staging for the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union Against Cancer Cancer Staging Manuals. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3763–3773. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Fiore F, Lecleire S, Pop D, et al. Baseline nutritional status is predictive of response to treatment and survival in patients treated by definitive chemoradiotherapy for a locally advanced esophageal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2557–2563. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatti I, Peacock O, Lloyd G, Larvin M, Hall RI. Preoperative hematologic markers as independent predictors of prognosis in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet-lymphocyte ratio. Am J Surg. 2010;200(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusumanto YH, Dam WA, Hospers GA, Meijer C, Mulder NH. Platelets and granulocytes, in particular the neutrophils, form important compartments for circulating vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis. 2003;6(4):283–287. doi: 10.1023/B:AGEN.0000029415.62384.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klinger MH, Jelkmann W. Role of blood platelets in infection and inflammation. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22(9):913–922. doi: 10.1089/10799900260286623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutta S, Crumley AB, Fullarton GM, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of the prognostic value of tumour and patient related factors in patients undergoing potentially curative resection of gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2012;204(3):294–299. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marrogi AJ, Munshi A, Merogi AJ, et al. Study of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and transforming growth factor-beta as prognostic factors in breast carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;74(5):492–501. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971021)74:5<492::aid-ijc3>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ropponen KM, Eskelinen MJ, Lipponen PK, Alhava E, Kosma VM. Prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 1997;182(3):318–324. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199707)182:3<318::AID-PATH862>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(3):203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klintrup K, Mäkinen JM, Kauppila S, et al. Inflammation and prognosis in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(17):2645–2654. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamieson NB, Mohamed M, Oien KA, et al. The relationship between tumor inflammatory cell infiltrate and outcome in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(11):3581–3590. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohashi Y, Ishibashi S, Suzuki T, et al. Significance of tumor associated tissue eosinophilia and other inflammatory cell infiltrate in early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(5A):3025–3030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi T, Teruya M, Kishiki T, et al. Inflammation-based prognostic score and number of lymph node metastases are independent prognostic factors in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2010;27(3):232–237. doi: 10.1159/000276910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vashist YK, Loos J, Dedow J, et al. Glasgow Prognostic Score is a predictor of perioperative and long-term outcome in patients with only surgically treated esophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(4):1130–1138. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]