Abstract

Our scientific knowledge of bullous pemphigoid (BP) has dramatically progressed in recent years. However, despite the availability of various therapeutic options for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, only a few multicenter controlled trials have helped to define effective therapies in BP. A major obstacle in sharing multicenter-based evidences for therapeutic efforts is the lack of generally accepted definitions for the clinical evaluation of patients with BP. Common terms and end points of BP are needed so that experts in the field can accurately measure and assess disease extent, activity, severity, and therapeutic response, and thus facilitate and advance clinical trials. These recommendations from the International Pemphigoid Committee represent 2 years of collaborative efforts to attain mutually acceptable common definitions for BP and proposes a disease extent score, the BP Disease Area Index. These items should assist in the development of consistent reporting of outcomes in future BP reports and studies.

Keywords: bullous pemphigoid, consensus, definitions, outcome measures, severity score

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is a common autoimmune bullous disease typically affecting the elderly. There have been only a handful of well-designed randomized controlled trials assessing the effectiveness of therapies for BP.1 In relatively rare diseases where it is difficult to include enough patients to have sufficient power to compare different treatments, meta-analysis is a powerful tool that is used to pool data across trials. However, it is impossible to compare the therapeutic outcomes from the majority of these BP studies using meta-analysis, as they have varying definitions and outcome measures.

PURPOSE

The purpose of this statement is to provide appropriate definitions for the various stages of disease activity, define therapeutic end points in BP, and to propose an objective disease extent measure that can be used in clinical trials. The use of the same definitions and outcome measures makes the results of trials more comparable. Since definitions and outcome measures for pemphigus2–4 have been published, most trials in pemphigus and reports have begun adopting these systems or referring to them when their existing trials using other measures were unable to show a difference.5

METHODS

An international BP definitions committee was organized in 2008, at the point when the international pemphigus definitions committee completed its similar work on pemphigus.2 The committee was an expansion of the first committee and convened 7 times over 2 years to discuss the appropriate definitions. These meetings were held at the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) annual meeting in San Antonio, TX, in 2009 (D. F. M. and V. P. W.); European Society for Dermatologic Research in Budapest, Hungary, in 2009 (D. F. M. and P. J.); the European Academy of Dermatovenereology in Berlin, Germany, in 2009 (D. F. M. and L. B.); the AAD in Miami, FL, in 2010 (D.F.M. and V. P. W.); the Pemphigus 2010 Meeting in Bern, Switzerland (V. P.W. and D. F. M.); and the International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Meeting at the National Institutes of Health in November 2010 (V. P. W. and D. F. M.), in Bethesda, MD. The final meeting was held at the AAD in 2011 in NewOrleans, LA (D. F. M. and V. P. W.). Meetings were supported in part by local dermatology societies. The draft definitions and end points were electronically mailed to the larger group, allowing for comments between meetings.

THE RECOMMENDATIONS

Observation points

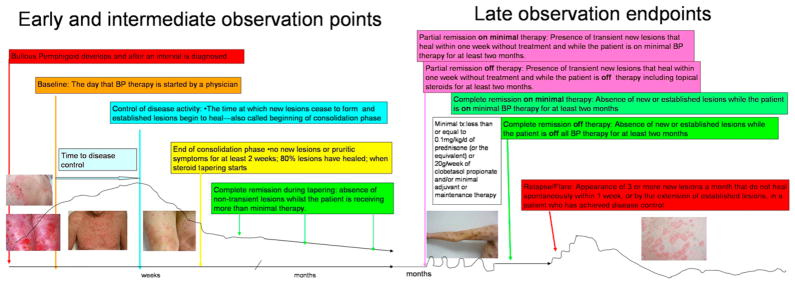

The end points are illustrated and summarized (Fig 1 and Table I).

Fig 1.

Pictorial depiction of end points in bullous pemphigoid.

Table I.

Definitions for bullous pemphigoid

| Early observation points | |

| Baseline | Day that BP therapy is started by physician |

| Control of disease activity | Time at which new lesions cease to form and established lesions begin to heal or pruritic symptoms start to abate |

| Time to control of disease activity (disease control; beginning of consolidation phase) | Time interval from baseline to control of disease activity |

| End of consolidation phase | Time at which no new lesions have developed for minimum of 2 wk and approximately 80% of lesions have healed and pruritic symptoms are minimal |

| Intermediate observation end points | |

| Transient lesions | New lesions that heal within 1 wk or pruritus lasting <1 wk and clearing without treatment |

| Nontransient lesions | New lesions that do not heal within 1 wk or pruritus continuing >1 wk with or without treatment |

| Complete remission during tapering | Absence of nontransient lesions while patient is receiving more than minimal therapy |

| Late observation end points | |

| Minimal therapy | ≤ 0.1 mg/kg/d Of prednisone (or equivalent) or 20 g/wk of clobetasol propionate and/or minimal adjuvant or maintenance therapy |

| Minimal adjuvant therapy and/or maintenance therapy | Following doses or less: methotrexate 5 mg/wk; azathioprine 0.7 mg/kg/d (with normal thiopurine s-methyltransferase level); mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg/d; mycophenolic acid 360 mg/d; or dapsone 50 mg/d |

| Partial remission on minimal therapy | Presence of transient new lesions that heal within 1 wk while patient is receiving minimal therapy for at least 2 mo |

| Complete remission on minimal therapy | Absence of new or established lesions or pruritus while patient is receiving minimal therapy for at least 2 mo |

| Partial remission off therapy | Presence of transient new lesions that heal within 1 wk without treatment while patient is off all BP therapy for at least 2 mo |

| Complete remission off therapy | Absence of new or established lesions or pruritus while patient is off all BP therapy for at least 2 mo |

| Mild new activity | <3 Lesions/mo (blisters, eczematous lesions, or urticarial plaques) that do not heal within 1 wk, or extension of established lesions or pruritus once/wk but less than daily in patient who has achieved disease control; these lesions have to heal within 2 wk |

| Relapse/flare | Appearance of ≥3 new lesions/mo (blisters, eczematous lesions, or urticarial plaques) or at least one large (>10 cm diameter) eczematous lesion or urticarial plaques that do not heal within 1 wk, or extension of established lesions or daily pruritus in patient who has achieved disease control |

| Failure of therapy for initial control | Development of new nontransient lesions or continued extension of old lesions, or failure of established lesions to begin to heal or continued pruritus despite: |

| Clobetasol propionate 40 g/d for 4 wk; or | |

| Prednisone 0.75 mg/kg/d equivalent for minimum of 3 wk with or without drugs used for maintenance therapy; or | |

| A tetracycline on full dosing for 4 wk; or | |

| Dapsone 1.5 mg/kg/d for 4 wk; or | |

| Methotrexate 15 mg/wk (if >60 kg and no major renal impairment) for 4 wk; or | |

| Azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg/d for 4 wk (if thiopurine s-methyltransferase level is normal); or | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil 40 mg/kg/d (if normal renal function, otherwise according to age/creatinine clearance) for 4 wk | |

BP, Bullous pemphigoid.

Early end points

“Baseline” is the point at which a physician starts treatment for BP.

“Control of disease activity” (disease control; beginning of consolidation phase) is defined as the point at which new lesions or pruritic symptoms cease to form and established lesions begin to heal. The time to disease control is the time between baseline and this control point.

“End of the consolidation phase” is defined as the time at which no new lesions or pruritic symptoms have developed for a minimum of 2 weeks and the majority (approximately 80%) of established lesions has healed. At this point tapering of corticosteroids often occurs. The length of the consolidation phase is the time between disease control and the end of consolidation phase.

“Transient lesions” are new lesions that heal within 1 week or pruritus lasting less than a week and clearing without treatment.

“Nontransient lesions” are new lesions that do not heal within 1 week or pruritus continuing more than a week with or without treatment.

Intermediate end points

During this period, the corticosteroids and other treatments are usually being tapered, but for some patients medication doses do not change because of flaring with attempts to taper treatment. “Complete remission during tapering” is the absence of nontransient lesions while the patient is receiving more than minimal therapy. There is no minimum time point here as the patient is under control but has not yet reached the desired outcome of disease remission on minimal or no therapy.

Late observation end points

Late observation end points of disease activity are identified as: (1) complete remission off therapy; and (2) complete remission on therapy, both of which only apply to patients who have had no new or established lesions for at least 2 months. “Complete remission off therapy” is defined as an absence of new or established lesions or pruritic symptoms while the patient is off all BP therapy for at least 2 months.

“Complete remission on therapy” is defined as the absence of new or established lesions or pruritus while the patient is receiving minimal therapy for at least 2 months. “Minimal therapy” is defined as less than or equal to 0.1 mg/kg/d of prednisone (or the equivalent) or 20 g/wk of clobetasol propionate and/or minimal adjuvant or maintenance therapy for at least 2 months, as shown in Fig 1 and discussed further below.

Minimal adjuvant therapy in BP corresponds to the following doses or less: methotrexate 5 mg/wk; azathioprine 0.7 mg/kg/d (with normal thiopurine s-methyltransferase level); mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg/d; mycophenolic acid 360 mg/d; or dapsone 50 mg/d. There has only been one small randomized controlled trial on tetracycline and niacinamide,6 which was underpowered because of low numbers and was unable to demonstrate a difference. Nevertheless, the committee’s expert opinion is that full therapeutic doses of the tetracyclines may work in localized forms of BP. As the tetracycline class of drugs is relatively nontoxic, the full therapeutic dose was listed among minimal therapies for BP.

“Partial remission off therapy” is defined as the presence of transient new lesions that heal within 1 week without treatment and while the patient is off all BP therapy for at least 2 months.

“Partial remission on minimal therapy” is defined as the presence of transient new lesions that heal within 1 week while the patient is receiving minimal therapy.

A newer term, “mild new activity,” refers to fewer than 3 lesions a month (blisters, eczematous lesions, or urticarial plaques) that do not heal within 1 week, or the extension of established lesions or pruritus once per week but less than daily, in a patient who has achieved disease control. This term was not included in the pemphigus definitions but the committee thought that it might be important to capture this phase during studies to determine if some patients with BP and certain characteristics or treatments experienced new mild activity not significant enough to constitute a flare. In this way, it could be determined in the future if these patients with BP might benefit from a change of treatment plan or not.

Relapse/flare

The terms “relapse” and “flare” are used interchangeably and are defined as the appearance of 3 or more new lesions a month (blisters, eczematous lesions, or urticarial plaques) or at least one large (>10 cm diameter) eczematous lesion or urticarial plaque that does not heal within 1 week, or the extension of established lesions or daily pruritus in a patient who has achieved disease control.

Treatment failure

“Failure of therapy for initial control” is defined as the development of new nontransient lesions or continued extension of old lesions, or failure of established lesions to begin to heal or daily pruritus despite certain strengths of corticosteroids with or without higher doses of adjuvants. The dose of prednisone defined as treatment failure is 0.75 mg/kg/d equivalent for minimum of 3 weeks. This dose was selected because the Cochrane review of interventions for BP1,7 determined that in acute BP there was no purpose in using prednisone at a higher dose than this. Topical clobetasol propionate at 40 g/d for 4 weeks was selected on the basis of the randomized controlled trials conducted by the French group.8,9 Other therapies include tetracycline at full doses for 4 weeks; dapsone 1.5 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks; methotrexate 15 mg/wk (if >60 kg and no major renal impairment) for 4 weeks; azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks (if thiopurine s-methyltransferase level is normal); or mycophenolate mofetil 40 mg/kg/d (if normal renal function, otherwise according to age/creatinine clearance) for 4 weeks. The definition does not imply these drugs and their respective doses are equivalent in therapeutic efficacy. Rather it provides a standardized agreement as to what can be defined as a failure of therapy.

BP disease activity index

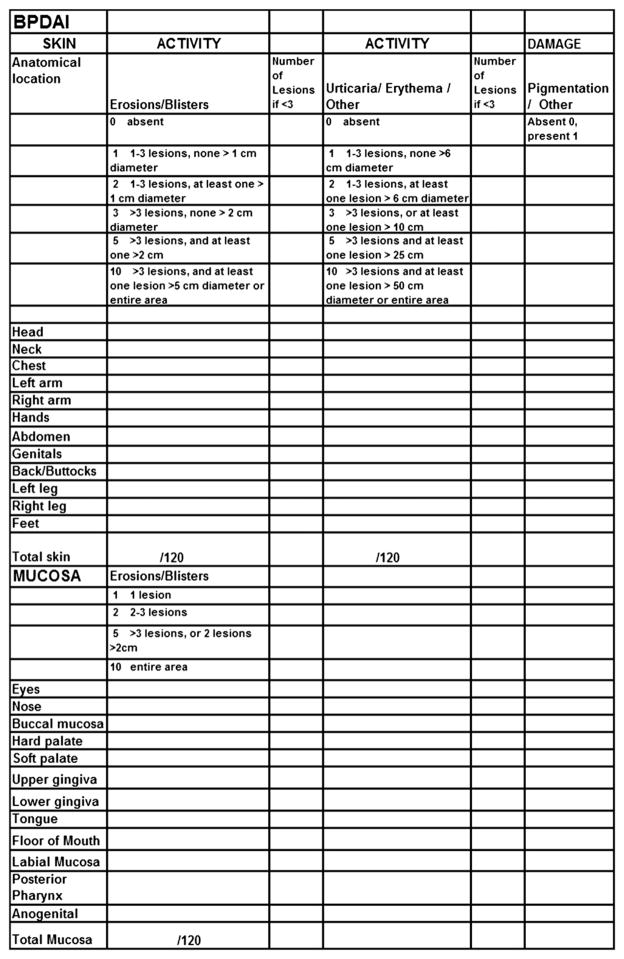

Like the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI),3 the BP Disease Area Index (BPDAI) measure has separate scores for skin and mucous membrane activity. Damage scores are separate as well and are included to remind physicians that not all visible lesions in BP represent active disease. Areas of the skin predominantly affected in BP10 were taken into account when selecting the skin sites so that trials would better differentiate clinical response in BP. Hence, additional weighting was given to the arms and legs and less emphasis to the face and scalp, slightly different from the PDAI. The mucous membrane areas were retained from the PDAI even though it is relatively rare to see mucous membrane involvement in BP, so that the activity could be compared with extent of mucous membrane involvement in different autoimmune bullous diseases. There are separate columns for the extent of blistering and for the urticarial/eczematous lesions that may be more extensive in BP.

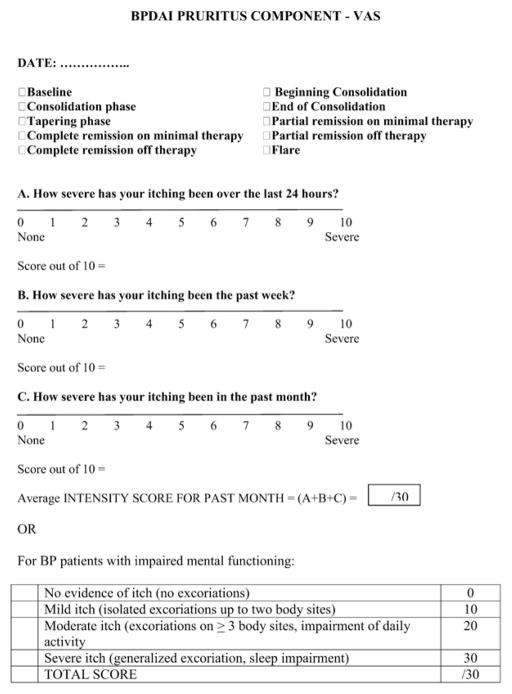

As a major symptom that may herald the onset and recurrence of BP is pruritus, a separate subjective component of the BPDAI is proposed to measure the severity of this (Fig 2). Naturally, other causes of pruritus in the elderly must be excluded, such as xerosis, dermatitis, renal impairment, liver impairment, and scabies. Providing that only pruritus related to BP is considered in the definitions and scored, this system can be used to subjectively grade the intensity of pruritus using a visual analog scale to answer the question, “How severe is your itching today?” and the patient marks an “x” on the 0- to 10-cm line where 0 is no itch and 10 is maximal itching. The degree of itching is measured as the distance in centimeters from 0, out of 10. This is repeated for the severity overall of itching in the past week and month. A total score is calculated from this out of 30. If the patient with BP is incapable of completing a reliable visual analog scale rating, for example, as a result of dementia, then the degree of pruritus is inferred, based on the extent of excoriations alone, also scored out of 30 (Fig 2). This subjective itch score will not be combined with the objective part of the BPDAI (Fig 3). Eventually, a quality-of-life tool for BP will be necessary as well. The BPDAI will be undergoing validation studies, similar to the partial validation done thus far with the PDAI.3

Fig 2.

Subjective Bullous Pemphigoid (BP) Disease Area Index (BPDAI ) pruritus score. VAS, Visual analog scale.

Fig 3.

Objective bullous pemphigoid disease area index

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Despite many trials evaluating therapeutic options for BP, it has been difficult to compare the results from these trials because of the large number of end points and definitions of disease. The formation of an international committee of bullous disease experts able to meet face to face on a regular basis has provided a mechanism for developing agreement on these issues for BP. This statement with agreed-upon common definitions, and the ongoing discussion and refinement of proposed common measurements for patients with BP, are the initial and necessary steps toward progress in the clinical evaluation and therapy of BP. Further progress and advancement will require a continued unified effort.

Acknowledgments

The International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Foundation generously supported renting rooms at the American Academy of Dermatology and audiovisual equipment; the European Society for Dermatological Research and European Academy of Dermatology provided meeting rooms. This report was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K24-AR 02207) to Dr Werth.

Abbreviations used

- AAD

American Academy of Dermatology

- BP

bullous pemphigoid

- BPDAI

Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index

- DAI

Disease Area Index

- PDAI

Pemphigus Disease Area Index

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

The following individuals who were unable to attend the meetings contributed by e-mail to the discussions: Cheyda Chams-Davatchi, Karen Harman, Pilar Iranzo, and Gudula Kirtschig. Molly Stuart and Will Zmchik at the International Pemphigus and Pemphigoid Foundation assisted with meeting setup.

References

- 1.Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, Murrell DF, Wojnarowska F, Khumalo NP. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD002292. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002292.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murrell DF, Dick S, Ahmed AR, Amagai M, Barnadas MA, Borradori L, et al. Consensus statement on definitions of disease, end points, and therapeutic response for pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:1043–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbach M, Murrell DF, Bystryn JC, Dulay S, Dick S, Fakharzadeh S, et al. Reliability and convergent validity of two outcome instruments for pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2404–10. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfutze M, Niedermeier A, Hertl M, Eming R. Introducing a novel Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score (ABSIS) in pemphigus. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:4–11. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorentino DF, Garcia MS, Rehmus W, Kimball AB. A pilot study of etanercept treatment for pemphigus vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:117–8. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fivenson DP, Breneman DL, Rosen GB, Hersh CS, Cardone S, Mutasim D. Nicotinamide and tetracycline therapy of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:753–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morel P, Guillaume JC. Treatment of bullous pemphigoid with prednisolone only: 0.75 mg/kg/day versus 1. 25 mg/kg/day; a multicenter randomized study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:925–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, Picard C, Dreno B, Delaporte E, et al. A comparison of oral and topical corticosteroids in patients with bullous pemphigoid. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:321–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joly P, Roujeau JC, Benichou J, Delaporte E, D’Incan M, Dreno B, et al. A comparison of two regimens of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with bullous pemphigoid: a multicenter randomized study. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1681–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard P, Vaillant L, Labeille B, Bedane C, Arbeille B, Denoeux JP, et al. Incidence and distribution of subepidermal autoimmune bullous skin diseases in three French regions; Bullous Diseases French Study Group. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]