Abstract

Creating integrated, comprehensive care practices requires access to data and informatics expertise. Information technology (IT) resources are not readily available to individual practices. One model of shared IT resources and learning is a “patient-centered medical village.” We describe the OCHIN Community Health Information Network as an example of this model where community practices have come together collectively to form an organization which leverages shared IT expertise, resources, and data, providing members with the means to fully capitalize on new technologies that support improved care. This collaborative facilitates the identification of “problem-sheds” through surveillance of network-wide data, enables shared learning regarding best practices, and provides a “community laboratory” for practice-based research. As an example of a Community of Solution, OCHIN utilizes health IT and data-sharing innovations to enhance partnerships between public health leaders, community health center clinicians, informatics experts, and policy makers. OCHIN community partners benefit from the shared IT resource (e.g. a linked electronic health record (EHR), centralized data warehouse, informatics and improvement expertise). This patient-centered medical village provides (1) the collective mechanism to build community tailored IT solutions, (2) “neighbors” to share data and improvement strategies, and (3) infrastructure to support EHR-based innovations across communities, using experimental approaches.

Keywords: community health, electronic health records, health information technology, practice-based research, community learning collaborative, quality improvement

The 1967 Folsom report entitled, “Health as a Community Affair,” called for the provision of high-quality comprehensive personal health services to all people in each community.(1) Over fifty years later, patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) are being created as a way to achieve this aim. The joint set of principles defining the PCMH laid out a framework to guide the coordination and integration of care as well as continual measurement of quality and improved outcomes.(2)To be successful in efforts to create an integrated, comprehensive care practice, PCMHs need to harness data. This requires information technology (IT), data resources, and sophisticated informatics expertise not readily available in most primary care practices, especially community health centers (CHCs) and other safety net organizations. Thus, there is concern that requirements to meaningfully use electronic health records (EHRs) and electronic data could widen disparities and leave safety net populations behind.(3-5)

One model to ensure IT support, data, and shared learning among community providers aiming to become PCMHs and to reach EHR meaningful use goals is that of an IT collaborative that serves as the hub for a “patient-centered medical village.” We describe the OCHIN Community Health Information Network as an example of this model where community health centers, advocacy organizations, and patients from multiple communities have come together collectively to form an organization that leverages shared IT expertise, resources, and data, providing them with the means to fully capitalize on new technologies that support improved care. OCHIN embodies a Community of Solution (COS) that supports the provision of high-quality comprehensive personal health services to individual patients while also utilizing its collective health IT and data resources to share knowledge and information across multiple PCMHs and public health organizations. This dual function highlights two of the grand challenges (#2 and #13) outlined by the Folsom Group in 2012.(6) The OCHIN patient-centered medical village demonstrates a model of partnerships between patients, community advocacy organizations, public health leaders, CHC clinicians, informatics experts, and policy makers. These partners worked together to create shared IT infrastructure (e.g., a linked EHR, centralized data warehouse and analytics, coupled with informatics and improvement expertise). OCHIN's centralized IT resource facilitates the identification of “problem-sheds” through surveillance of network-wide data, enables shared learning regarding best practices, and provides a “community laboratory” for practice-based research. This COS model of a patient-centered medical village provides (1) the collective mechanism to build community tailored IT solutions, (2) “neighbors” to share data and improvement strategies, and (3) infrastructure to support EHR-based quality improvement innovations across communities, using experimental approaches. In this model, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Phase 1: Creating OCHIN and Building the IT Foundation

In 2001, CHCs governed by patient boards, community advocates, and other safety net organizations from multiple communities formed a member-based, non-profit collaborative, originally called the Oregon Community Health Information Network (renamed “OCHIN, Inc.” as members from other states joined), to facilitate adopting health IT and a learning environment to improve care quality for vulnerable populations. This community collaborative enabled shared purchasing by multiple organizations, making it possible for the network to purchase an EHR that would have been unaffordable for individual members on their own. OCHIN is a non-profit 501(c)(3), governed by a community board of directors, the majority of whom are community members of the collaborative. OCHIN provides and maintains a comprehensive electronic health information infrastructure for patient data through an Organized Health Care Arrangement, which is recognized in the HIPAA privacy rules and allows two or more covered entities participating in joint activities to share protected health information about their patients in order to manage and benefit their joint operations. This arrangement gives patients receiving care from any OCHIN clinic a single medical record number, allowing clinical and utilization data to “follow the patient” to any OCHIN clinic. Member clinics share OCHIN's fully integrated EHR, which is built on software from EpicCare© Systems and includes a practice management data system (claims, billing, appointments) and an EpicCare© electronic medical record.

Among the first major challenges in building OCHIN was choosing an EHR vendor and negotiating the initial EHR purchase. The centralized, integrated, technical model of EpicCare© was a good fit for the OCHIN centrally-hosted business model. It was also important to find a vendor who was willing to be a partner amenable to making system modifications and enhancements for the organization. In addition, OCHIN wanted to maintain full access to all of the network's EHR data, preferably through a library of reports accompanied by an easy-to-use query tool for non-technical users. EpicCare© did not have this function, so OCHIN helped members to fill this gap by identifying supplemental products.

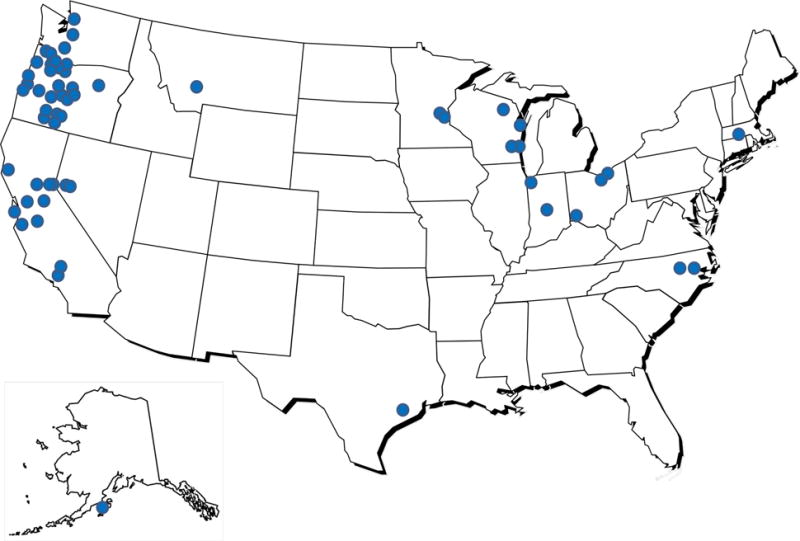

The OCHIN collaborative now includes over 60 members with more than 200 clinic sites providing a broad spectrum of primary health care services (e.g. preventive care, public health, maternal and child health, behavioral/mental health, school-based services, dental services, and care based in corrections facilities); see Figure 1 for a map of current OCHIN members' locations. Most OCHIN members are federally-qualified health centers, rural health centers, and school-based health centers. OCHIN member clinics care for more than one million patients annually with over three million visits. Some of the vulnerable populations served by these clinics include: uninsured and underinsured patients, racial and ethnic minorities, migrant and seasonal farm workers, and patients living in poverty.

Figure 1. Map showing the location of OCHIN member clinics.

Because the EHR is centrally hosted at OCHIN and linked across all member clinics, each patient has a single medical record that is accessible to providers across the collaborative via an enterprise-wide master patient index. There are many advantages to the shared EHR including the seamless exchange of information between all OCHIN member clinics, which improves communication, integration, and coordination of care for complex patients and migrant populations. Data can also be centrally collected for quality improvement, public health surveillance (e.g., tracking community influenza outbreaks), population health initiatives, research, and reporting purposes. The EHR data are standardized across sites, and regularly checked for accuracy as part of OCHIN's member support.

While the diverse collaborative was an asset, it also posed some challenges such as the need to harmonize different clinical, billing, and reporting structures across the network, and achieving information sharing agreements that complied with HIPAA and other privacy regulations. There are economies of scale to be gained by pooling and sharing resources, yet each member organization has its own needs and wants. OCHIN has learned that the tenets of the Pareto principle hold true when bringing new members into the collaborative and serving their needs: in most cases, approximately 80% of a new member's needs can be met by the collective resources; however, individualized and customized products are required to meet the additional 20%. Managing these collective and individual needs is required both during “go-live” EHR installations but also on an ongoing basis, through continued support, training, and enhanced IT tools. This requires constant attention to needs, prioritization of projects, and a skilled workforce. OCHIN has learned to offer products and services that are flexible to changing clinic needs and adaptable to the changing health care policy environment. This requires sophisticated change management approaches and peer interventions to help members achieve the best outcomes. OCHIN has developed internship and apprenticeship programs necessary to train and maintain the personnel with the highly technical skills required to support this patient-centered medical village. It takes several years to build the interdisciplinary skills necessary to coach and mentor practices in the adoption of new IT tools and associated workflow changes. These important partnerships and training opportunities have strengthened the community of solution.

In this first phase of OCHIN's development, we built community IT infrastructure, data resources, and a skilled IT workforce, that provided a solid foundation for moving together collaboratively to enhance tools, data extraction, and shared learning across the patient-centered medical village.

Phase 2: Enhanced Data Systems, Governance, Shared Learning, and Practice-based Research

Enhanced Data Systems

The centralized OCHIN infrastructure enabled the customization of a shared EHR platform and the development of EHR-enhancing tools. OCHIN optimizations to meet the needs of unique populations within the larger community included tailored systems for revenue management and billing (e.g. charity programs, Medicaid), federal and state reporting (e.g. Uniform Data System [UDS] measures collected by the Health Resources and Services Administration [HRSA]), interoperability development, and integrated services (e.g. OCHIN's Behavioral Health navigator to support the integration of primary care and mental health services). The OCHIN collaborative also facilitated member supports such as: interfaces to supplement the EHR with external information (e.g., labs, images), and secure data interchange with federal and state agencies (e.g., federal Social Security Administration, state Medicaid, state immunization registry). These efforts were largely focused on building interfaces that best supported integrated and coordinated care by facilitating the movement of data from primary care, mental health, and public health providers on behalf of the patient. These external connections were vital for PCMHs serving populations who were also receiving services at other sites (e.g., migrant farm workers, patients receiving immunizations and screening for sexually transmitted diseases at the public health department).

As OCHIN evolved, we recognized the need to maintain a network-wide electronic data warehouse that captured, stored and maintained all data from the EHR. To optimize the use of this data in providing high-quality, integrated, comprehensive personal health services to patients, there was a need for supplemental software to aggregate data elements from the EHR warehouse and present the results in a user-friendly format. OCHIN helped to develop an open-source reporting tool that aggregates data from multiple locations in the EHR and presents the results in a common format, enabling providers to manage quality improvement. This data aggregator is implemented in standard SQL and contains a library of user-expandable metrics. A harvesting engine gathers necessary fields from electronic data sources including practice management, billing, medical records, laboratory, claims, disease management systems, public health reporting, and pharmacy data. It includes custom extractors to retrieve data from these systems, but data can also be entered directly. The harvesting engine includes tools to clean the data and assist with merging records. A calculation engine uses tables from the harvesting engine to produce metrics and build unique tables for creating registries and identifying patients in need of services. With the shared resources at OCHIN, it was possible to tailor this software for use in community settings, enhance its data warehouse and calculating functions, add a business intelligence interface, and train clinicians and staff across the collaborative to use it for clinical decision support, reporting, and other panel management activities.

Having the ability to extract and aggregate EHR data across a network of PCMHs also supports public health surveillance and population health planning. It enables the identification of “problem-sheds,” whether these be geographic locations, racial/ethnic groups, certain chronic diseases, or other populations in need of more intense assistance and intervention. This information can be shared with multiple partners in the collaborative, including public health agencies and other state and federal offices responsible for monitoring the health of special populations and targeting resources to where they are needed most.

Governance and Advisory Groups

OCHIN has a board of directors from communities across the country that makes major business decisions. However, a unique feature of the collaborative is the process through which members have input on the shared EHR, the further development of clinical decision support tools, and the ways that data are used. OCHIN hosts regular meetings of the Clinical Operations Group (COG) comprised of clinical leaders from all member organizations. Members of this group, some of whom have been working together for over eight years, review proposed changes to the shared EHR and guide quality improvement activities and population health initiatives across the collaborative. Executive leaders from the membership meet together twice years, as the Executive Strategic Oversight Council (ESOC), to provide strategic direction regarding issues that affect clinic operations. The COG and ESOC are chaired by members and have traditionally made decisions by consensus. As the collaborative has expanded to its current size, making decisions by consensus has become more challenging, and there is movement towards the election of a representative advisory council which would be smaller in size, meet more frequently, and have the ability to assist staff with efficient and nimble prioritization and optimization. The organization is moving cautiously in this direction so as not to marginalize some of the smaller member clinics.

Shared Learning about Best Practices

Not only do members share a common EHR hosted by OCHIN, but these practices are all transforming into PCMHs and striving to meet EHR meaningful use goals. Within the OCHIN collaborative, individual clinics are already engaged in cutting-edge innovations to meet local, state, and national goals. The regular COG and ESOC meetings have enabled members to come together and share best practices and lessons learned regarding workflow changes needed to realize PCMH goals. The collaborative and its member groups also provide a structured environment with peer mentors and a shared EHR to enable practices to come together, share their individual innovations, and spread them across the network. In other words, this patient-centered medical village provides the platform to support, facilitate, scale up and spread what many clinics are already doing. It also creates the energy and buoyancy to lift members to the next level of improvement work and practice transformation. Further, by utilizing health IT and data-sharing across the network, relevant knowledge can flow more widely and efficiently to support action planning for community health services, as recommended in the original Folsom report in 1967 and highlighted as grand challenge #13 by the Folsom Group in 2012(1, 6).

Practice-based Research

In this phase of OCHIN's development, there was also recognition from key leaders and stakeholders that this organization was uniquely positioned as a “community laboratory” for practice-based research that could inform practice and policy change. With funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, OCHIN has developed a robust practice-based research infrastructure, partnering with academic researchers interested in studying innovations across the network. The OCHIN SafetyNetWest Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) is registered with the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.(7, 8) Clinicians and researchers affiliated with the PBRN meet monthly to review and provide feedback on proposed research projects that would take place in member clinic sites, utilize OCHIN data, and/or require other network resources.

The OCHIN research team is engaged in a variety of research projects including the analyses of large datasets to study the impact of practice and policy changes, the development of natural language processing software, and testing the feasibility of translating clinical and system interventions proven effective in integrated care settings into safety net clinics. The OCHIN collaborative also provides a unique “community laboratory” for conducting dissemination and implementation research because it can support cluster randomized trials that test system and/or IT interventions, such as the introduction of new electronic clinical decision support tools or new quality improvement strategies.

Measuring the Progress of the OCHIN Community of Solution

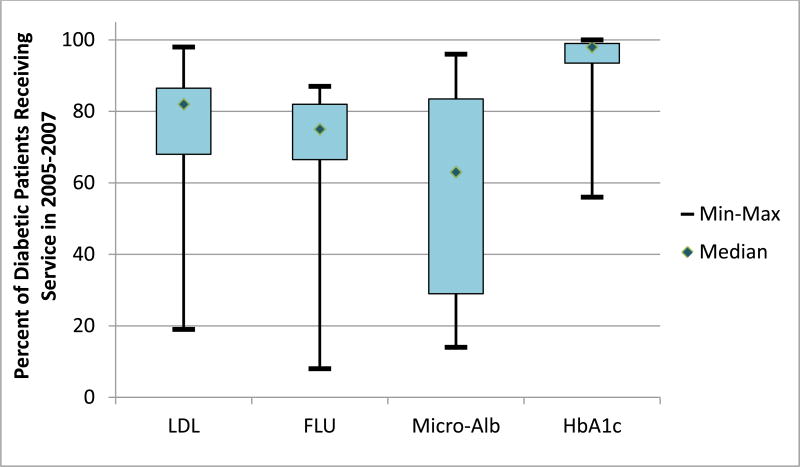

There are a couple of ways in which the progress of this unique COS can be measured. First, the OCHIN collaborative is committed to helping members achieve stage one EHR meaningful use goals by building and installing IT systems, helping practices stabilize and optimize those systems, and training clinic staff to utilize these systems to their fullest capabilities. OCHIN plans to continue supporting members in their goals to reach EHR meaningful use stage two and three benchmarks as early as possible; these achievements can be measured. Similarly, we can measure the success of member practices in meeting PCMH standards, especially those most relevant to EHR and data use. Second, the OCHIN data repository allows for longitudinal measurement of numerous quality metrics as a means to follow trends over time and to scan across member clinics to identify those who are most in need of assistance (and others who can offer assistance). This approach to identifying problem-sheds and measuring success enables OCHIN to use its data warehouse to conduct surveillance across the network. For example, in one analyses of network-wide data from 2005-2007, we found wide variation among diabetics receiving preventive care services across our network (Figure 2).(9) This surveillance capability allows us to identify which sites are doing well, study their approach and processes, and then spread those lessons to sites that are struggling. It also enables us to better understand how the demographics of patient panels differ between sites and which characteristics are most predictive of variations in performance. This information is highly relevant to shape policies that continue to incentivize clinics to care for these vulnerable populations rather than penalize clinics for doing so.

Figure 2. Variability in diabetes preventive care quality across the network, in % of patients receiving diabetes preventive services.

LDL: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol screening

FLU: influenza vaccination

Micro-Alb: urine microalbumin (nephropathy screen)

HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin screening

A measurement approach that targets meeting both individual and collective improvement goals is important to assess the impact of our patient-centered medical village on improving the health of vulnerable populations and eliminating health care disparities. It also pushes the paradigm shift one step further, from treating individual patients to managing a community health center patient panel to improving the care of populations across a network of community health centers.(6)

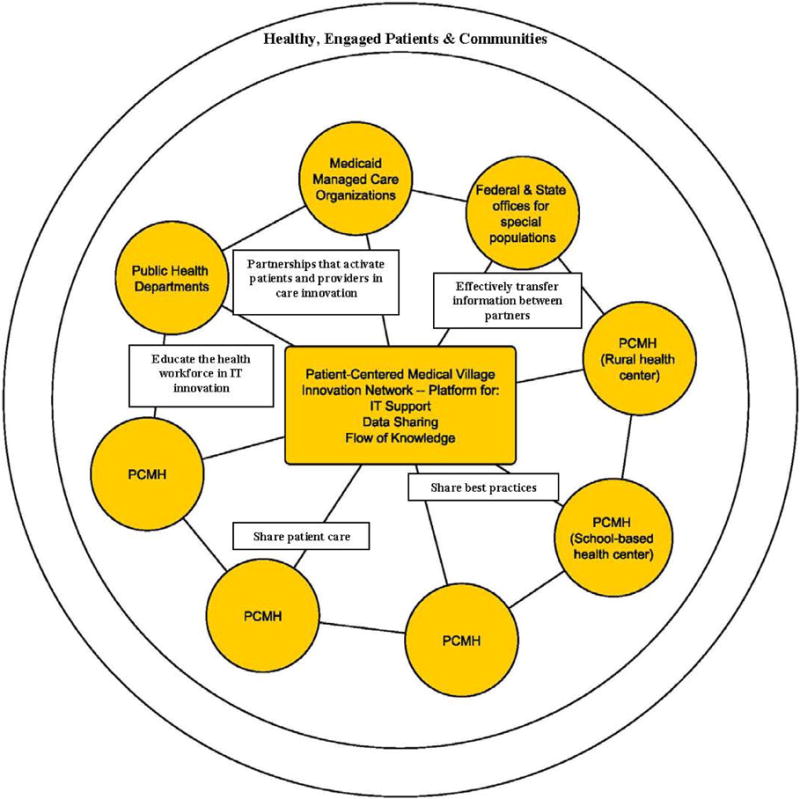

The OCHIN model of a centralized data warehouse coupled with a team of highly skilled informatics and analytics experts provides resources for member practices beyond what each could do individually. It does not, however, require the individual entities to merge or be subsumed into a larger integrated system. This collaborative model between independent organizations allows each to maintain autonomy to innovate in ways that address the diverse communities and cultures they serve. Individual members also play a central role in the governance of the organization and common ownership in the health IT tools, processes, and relationships that bind members together with a mission to serve the underserved (Figure 3). If PCMHs are to be truly successful, clinics cannot go it alone; they must have shared IT and data resources coupled with meaningful opportunities to share best practices and get support from colleagues.

Figure 3. The OCHIN Patient-Centered Medical Village model enables a linked electronic health record, shared health IT infrastructure, and collaborative learning across Patient-Centered Medical Homes and other healthcare entities.

PCMH: patient-centered medical home

IT: information technology

Phase 3: Future Vision

As the OCHIN collaborative continues to grow, we hope to add the following enhancements in the near future: (a) patient engagement in setting priorities and (b) a longitudinal fellowship training opportunity for member clinicians.

(a) Engaging Patients Through a Virtual Network

As OCHIN continues building the infrastructure for a patient-centered medical village, the new IT tools supporting this collaborative will also enable more meaningful engagement of patients in efforts to improve care quality. Modeled after the Public Insight Networks in the media industry, we plan to create the OCHIN Patient Engagement Network (OPEN), designed as a virtual network of patients across the country who will regularly contribute their important perspectives to the collective “bank of insights” guiding the development of patient-centered improvements, measurement, evaluations. This will be accomplished by recruiting a national cohort of patients for remote engagement in research and priority-setting via the personal health record/patient portal in the OCHIN EHR. Patient participants in OPEN will have the opportunity to participate in ongoing communication via a private blog and will be invited to complete brief (3-4 questions) electronic surveys on a regular basis to solicit their ongoing input and feedback regarding their perspectives on topics and issues important to research and quality improvement. The virtual network will be designed and facilitated in close collaboration and partnership with our PBRN patient engagement panel. This vision aligns with the Folsom report recommendation to organize and deliver community health services outside of traditional boundaries or political jurisdictions and addresses grand challenge #1 put forth by the Folsom group by utilizing IT resources to create a national platform for engagement and activation of patients.(1, 6)

(b) Longitudinal Fellowship Training for Physicians and Community Health Teams

A patient-centered medical village, such as the one we are building at OCHIN, needs “village champions.” Similar to “clinician champions” who are key to the success of practice-based research and quality improvement projects, we plan to expand upon our internship programs to create specialized training for individuals willing to lead and facilitate the collaborative sharing and spread of ideas across the village. Rather than remove leaders from their communities to participate in a full-time fellowship, we envision creating longitudinal part-time opportunities for clinicians to stay grounded in their community health centers while simultaneously participating in a cohort of fellows to work in an apprenticeship-type arrangement. In this model, fellows would routinely travel to the “hub,” helping to build the village while expanding their toolkit of IT and quality improvement skills for village leadership in the future. Many of these skills are what the Folsom Report described as necessary for the “ideal primary care physician” who is “the central point for integration and continuity of all medical and related services.”(1, 6) This training opportunity would include some of the traditional training in public health, improvement science, and informatics degree programs, but it would also capitalize on “hands-on” learning sitting elbow-to-elbow with information architects, workflow engineers, systems scientists, research analysts, and improvement experts. Learners would bring new ideas and infuse enthusiasm into activities happening at the hub; thus, the flow of information, knowledge, and energy would be bidirectional. By contributing to the future health care workforce and also enhancing the ability of a team of health professionals to utilize integrated community health services, this addresses the Folsom Group's grand challenge #3 and #9.(6)

Conclusion

The patient-centered medical village model creates an IT hub to support the development of integrated, comprehensive care practices and action planning for community health services. If organized well, a patient-centered medical village can meet many clinical and organizational goals while shifting the focus to improving population health collectively. Capitalizing on a linked EHR, shared IT infrastructure, and collaborative governance structure, the OCHIN patient-centered medical village was created to have meaningful impact on reducing health care disparities. This model is also designed to engage clinicians and patients in collaborative efforts to improve population health. As this model evolves and community members learn to harness the power of the collective data resources and learning collaborative, it is hoped that shared IT resources and data will be used more fully and effectively to support the provision of high-quality comprehensive personal health services, improved community health and action planning for community health services, and policy advocacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Sonja Likumahuwa, Jon Puro, Jill Arkind, Rachel Gold, Vance Bauer, Christine Nelson, Steffani Bailey, and Jean O'Malley.

Funding: The development of research infrastructure at OCHIN was supported by grant number 1RC4LM010852 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Library of Medicine and grant number UB2HA20235 from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The data analyses that informed examples of measurement in this paper were supported by grant R01 HL107647 from the NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. These funding organizations had no involvement in the design, preparation, review, or approval of this commentary.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Abigail Sears is the Chief Executive Officer of OCHIN. Jennifer DeVoe is the Executive Director of OCHIN's Practice-based Research Network.

Human Subjects: The data included in this manuscript was from an ongoing study at OCHIN approved by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board (OHSU #IRB 5536).

Contributor Information

Jennifer E. DeVoe, Email: devoej@ohsu.edu, Executive Director, Practice-based Research Network, OCHIN, Inc., 1881 SW Naito Parkway, Portland, OR 97201; Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University.

Abigail Sears, Email: searsa@ochin.org, Chief Executive Officer, OCHIN, Inc., 1881 SW Naito Parkway, Portland, OR 97201.

References

- 1.National Commission on Community Health Services (NCCHS) Health is a Community Affair-Report of the National Commission on Community Health Services (NCCHS) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. 2007 Mar; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Services HaH. Federal Health Information Technology Strategic Plan 2011-2015. Washington D.C.; 2011. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xierali IM, Rinaldo JC, Green LA, Petterson SM, Phillips RL, Jr, Bazemore AW, et al. Family physician participation in maintenance of certification. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(3):203–10. doi: 10.1370/afm.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meaningful Use Workgroup, Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, US Department of Health and Human Services. Using HIT to Eliminate Disparities: A Focus on Solutions. Washington, D.C.: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folsom Group. Communities of solution: the Folsom Report revisited. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(3):250–60. doi: 10.1370/afm.1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devoe JE, Gold R, Spofford M, Chauvie S, Muench J, Turner A, et al. Developing a network of community health centers with a common electronic health record: description of the Safety Net West Practice-based Research Network (SNW-PBRN) J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(5):597–604. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeVoe JE, Likumahuwa S, Eiff MP, Nelson C, Carroll JE, Hill CN, et al. Commentary: Developing a New PBRN: Lessons Learned and Challenges Ahead. J Am Board Fam Med. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.120141. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVoe J, Gold R, O'Malley J, Bailey S, Puro J, McIntire P. Variability in Care Quality: Do Federally-Qualified Health Center Patient Demographics Correlate with Quality of Diabetic Care?. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting; Orlando, FL. 2012. [Google Scholar]