Abstract

Poor and racial/ethnic minority women comprise the majority of women living with HIV (WLH) in the United States. Race, gender, class, and HIV-based stigmas and inequities limit women’s powers over their health and compromise their quality of life. To help WLH counter this powerlessness, we implemented a photovoice project called Picturing New Possibilities (PNP), and explored how women experienced empowerment through photovoice. PNP participants (N = 30) photographed their life experiences, attended 3 group discussions and a community exhibit of their photos, and completed a follow-up interview. We used strategies of Grounded Theory to identify key empowerment themes. Participants described empowerment through enhanced self-esteem, self-confidence, critical thinking skills, and control. Our findings suggest that photovoice is an important tool for WLH. It offers women a way to access internal strengths and use these resources to improve their quality of life and health.

Keywords: empowerment, photovoice, racial/ethnic minorities, women living with HIV

Photovoice is a participatory process in which underserved individuals identify, represent, and enhance their lives and communities through photography (Wang, 1999). It originated as a community-based participatory research and needs assessment tool. Wang and Burris (1994) first applied photovoice to public health in the early 1990s to give women in rural China an opportunity to define and share their reproductive health experiences and needs. Since then, the method has been used extensively to achieve a number of diverse public health goals. As a research methodology, the process aims to enable people to identify their personal and community health needs, promote critical dialogue about these experiences, and create a forum by which participants can inform health policy with their images and experiences (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). Photovoice is based on the assumption that marginalized community members and their ideas about their health are important and influential. Thus, the process also facilitates empowerment (Wang, 1999; Wang & Burris, 1994).

Photovoice empowers participants via a process called Empowerment Education (Freire, 1970). Developed by the Brazilian Educator Paulo Freire, Empowerment Education educates people in a group setting to identify their needs, defines the causes of their problems, shares similar experiences and solutions, and takes action to address concerns (Freire, 1970). Sharing and disseminating photos defines the Empowerment Education steps. The pictures form the curriculum from which participants can represent their experiences, analyze the meaning of their experiences, and share and act on solutions (Wang, 1999).

Despite the centrality of empowerment to photovoice, there have been few explanations of how the photovoice process leads to reports of empowerment (Carlson, Engebretson, & Chamberlain, 2006; Duffy, 2011; Foster-Fishman, Nowell, Deacon, Nievar, & McCann, 2005). Existing research begins an important and general dialogue about common empowerment components (such as enhanced control and problem-solving capabilities) described by participants (Carlson et al., 2006; Duffy, 2011; Foster-Fishman et al., 2005), yet unanswered questions remain about what these experiences mean to participants and how the photovoice experience supports empowerment. Moreover, none of the existing research has focused on the experiences of women living with HIV (WLH), who face unique challenges and needs as a result of their gender, socio-economic, and illness-based powerlessness. Thus, we draw on Picturing New Possibilities (PNP), a pilot photovoice project conducted with women living with HIV (WLH), to explore women’s experiences of empowerment through photovoice.

HIV is a significant and growing public health concern among women in the United States, especially marginalized and vulnerable women. For example, the vast majority of WLH are members of racial/ethnic minority communities. Although Black and Latina women comprise only 25% of the U.S. population of women, they account for 80% of new HIV infections among women (CDC, 2013). Newly released data from the The Women’s HIV SeroIncidence Study indicated that HIV incidence among Black women is comparable to HIV adult incidence rates in parts of sub-Saharan Africa (Hodder et al., 2012). In addition to these glaring racial/ethnic disparities, women with HIV contend daily with myriad other socioeconomic, gender, and health-based inequalities. These include poverty, few education and employment opportunities (CDC, 2013), homelessness or unstable housing (Kidder, Wolitski, Pals, & Campsmith, 2008), relationship violence (Gielen et al., 2007), trauma (Machtinger, Wilson, Haberer, & Weiss, 2012), HIV stigma (Carr & Gramling, 2004), and discrimination (Wingood et al., 2007). Together these inequalities limit women’s power and capacity to make healthy choices in their lives – increasing women’s vulnerability to HIV in the first place, and, once living with the virus, reducing their ability to engage in healthy behaviors to protect themselves and others (Adimora et al., 2006; Kalichman & Grebler, 2010; Riley, Gandhi, Hare, Cohen, & Hwang, 2007; Teti, Bowleg, & Lloyd, 2010).

To help WLH counter the helplessness and powerlessness they experience, we implemented Picturing New Possibilities (PNP). As a research methodology, photovoice has been implemented extensively with a number of vulnerable and underserved populations (Catalani & Minkler, 2010), but in our study, we extended photovoice beyond a research tool, as a way to help women understand their experiences and affect change in their lives amid their challenges. Our qualitative analysis adapted Grounded Theory strategies to explore women’s experiences of empowerment through photovoice.

Methods

Participants

PNP was approved by the primary author’s university institutional review board. PNP participants were recruited from AIDS service organizations (ASOs – clinics, case management organizations) in three U.S. cities in the Midwest and Northeast. Women were recruited by placing project flyers in ASOs serving WLH and by meeting with local HIV providers and support groups for WLH to describe the project and invite participants. Interested participants contacted the research team to complete an eligibility screening questionnaire. Eligibility included: (a) being female, (b) ages 18–65, (c) able to speak and understand English, (d) having HIV, and (e) agreeing to take and share photographs.

We recruited 32 women; two participants were lost to follow-up for illness and unknown reasons. The final sample included 30 women, a sufficient sample size for qualitative data analysis and saturation (Charmaz, 2006), particularly for photovoice projects in which data include rich details in text and images (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). The majority of the participants were African American (81%). Two women identified their race/ethnicity as Other and four women identified as White. Participants’ mean age was 45 (range 19–61), and, on average, they had been living with HIV for 11 years (range 6 months to 17 years). Reported income ranged from $0 to $30,000 per year. Participants did not differ demographically across study locations.

Project Procedures

The Principal Investigator (first author) facilitated PNP with assistance from a Research Assistant or a Nurse Practitioner from the key recruiting sites. The facilitators delivered the project to women in five separate groups, which ranged from 4–8 participants, from November 2009 to November 2011. Each group included 3 weekly 2-hour meetings. During the first session, the facilitator explained that the purpose of the project was for women to share and address their life experiences, strengths, and challenges through photos. Together, the participants brainstormed different potential ideas for photographs and discussed the ethics of picture taking. For example, participants discussed situations that they should not photograph and learned how to obtain consent (i.e., a written release) to take pictures of other people. Each woman received a camera to keep. The facilitators showed the women how to use the camera and the participants practiced taking pictures and performing basic camera functions.

During the second and third meetings, the participants reconvened to review and discuss their photographs. The facilitators led these discussions, using a laptop computer to download digital photos and display them via a projector. The session included individual presentations and group discussions of the photos. First, each participant presented 2–4 photos of her choice to the group and discussed what each photo meant to her. We facilitated these discussions using a variation of the SHOWeD technique, a well-established technique to guide photovoice discussions (Catalani & Minkler, 2010; Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001). The SHOWeD process includes a series of five questions designed to help photovoice participants talk about their photos: What do you See here? What is Happening? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this problem or strength exist? and What can we Do about it? We tailored the questions to focus on HIV by adding or substituting a few additional prompts: What does the photo capture about HIV? What story does the photo tell about your life with HIV? How does the photo capture [a particular challenge or strength] with HIV? The SHOWeD process facilitated a description of the photos and encouraged critical thinking to resolve or address challenges raised. After each participant presented and discussed her photos, the group discussed their reactions to the images.

Most of the women (83%) attended all of the sessions. In each city, during the final meeting, the group planned a public showing of the photos. Each woman signed a release and chose to present some of her photos at a public HIV community event. The exhibit was optional, but 70% of the women chose to participate in the exhibit. The women who did not attend had schedule conflicts or chose not to reveal themselves at an HIV-related event. Women who did not want their photos to be shown publically still showed and shared their pictures in group sessions.

Following the exhibit, the Principal Investigator conducted 1- to 2-hour individual-level interviews with each participant to explore her experience in the project and how the project facilitated empowerment and/or affected her. Specifically, the questions were designed to capture participants’ reflections about the process. Examples of questions from the interview guide included: “How would you describe the project to someone else?”, “What did you learn about yourself in the project?”, “What changed about you throughout the project?”, “Describe the experience of watching other people view your photos.” We offered the follow-up interviews to women in two of the three study sites (n = 20) and all 20 of the women participated in follow-up interviews. In addition to receiving the camera, all of the women were compensated monetarily for their time and received $15, $20, and $25 for attending the discussion groups and $50 for completing the follow-up interview. We digitally recorded each group and individual intervention session to capture project data. During the group sessions, one facilitator took notes to record the project processes and link discussions to specific photos being presented.

Data Analysis

Charmaz’(2006) guidelines for constructing grounded theory guided our analysis. Charmaz (2006) viewed grounded theory methods as a set of flexible practices and adapted necessary aspects of the process, without following a rigid prescription of all of the original theory components (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). For example, Charmaz (2006) noted that it was important to prioritize the experiences voiced by participants but that it was difficult to conduct analyses without a frame of reference. To that end, Wang and Burris’ (1994) classic description of the empowerment process intended to result from photovoice served as a general guide for our analysis. Wang and Burris (1994) defined individual-level empowerment as self-development, problem analysis, and change skills. We analyzed the data to understand how women experienced empowerment, as defined generally by these terms. Yet to remain fully committed to the participants’ experiences, we were open to understanding unique dimensions of empowerment from participants’ lived experiences as well as their perspective of the meaning of empowerment in their lives.

Project data were rich and included approximately 300 photographs, 15 group session transcripts (35 pages of data per group, on average), and 20 individual interview transcripts (14 pages of data per interview, on average). We transcribed all of the group sessions and interviews verbatim, and edited them for clarity only. We entered the transcripts into Atlas.ti (Scientific Software Development, 2011), a qualitative software analysis package to facilitate data coding. The first and second authors reviewed the transcripts and photos multiple times to become familiar with the data and key themes. Then we created a codebook describing the most salient empowerment themes, and conducted a content analysis of the data using two strategies: coding and analytical memos (Charmaz, 2006). Coding matched text to themes and progressed in two stages, open or more general coding, which was followed by selective or more specific coding (Charmaz, 2006). We wrote analytical notes throughout all phases of coding to highlight key questions about relationships in the data and to refine codes. After coding the data, we generated coding reports that collated the evidence for each theme and reviewed and discussed the reports and analysis notes to write the results section.

We assured the quality or trustworthiness of our analysis in several ways (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). First, by facilitating the sessions and reviewing the transcripts in detail, we gained sufficient knowledge about the data to perform the analysis. In addition, during data debriefing sessions, the first and second authors discussed coding differences until we reached a sufficient level of agreement about discrepancies. Third, planning the photo exhibit served as a form of “member checking,” in which participants could also review and discuss major analysis findings for dissemination and assure that these findings represented their experiences appropriately (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Participants read parts of the transcripts that correlated with their photo discussions and worked with the researchers to draft photo captions and clarify text if needed. Versions of these captions appear in this article.

Finally, we attended to trustworthiness via reflexivity or by describing the role of the researchers in multiple steps of this analysis including data collection and the choice of photos for publication. The facilitators of the group sessions differed in key ways from participants, such as race/ethnicity, socio-economic, and HIV statuses. These power differentials may have limited or affected participant willingness to share intimate details about their lives or illness experiences. One facilitator was a nurse practitioner at one of the sites. As a result, women at that site may have been reluctant to discuss or address issues of medical care. Participants worked collaboratively with the lead author to choose photos for publication – but only photos with sufficient signed photos releases could be used. This limited the photos available for publication.

Results

Participants described empowerment through four key concepts: (a) self-esteem, (b) self-confidence, (c) critical thinking skills, and (d) enhanced control. In sum, as a result of PNP, participants reported feeling better about their lives and more confident about their own power and abilities. They began to think about their circumstances in new ways – all of which enhanced their control over HIV and life challenges. We describe these four themes in detail with quotes and pictures from participants. Pseudonyms replace participants ‘names to protect their identities.

Building Self-Esteem and Recognizing Self-Worth

Many of the women in our study reported that participating in PNP enhanced their self-esteem and self-worth. The women commonly reported that the project helped them to realize that they mattered and to feel “proud,” “important,” “validated,” and “beautiful.” Specifically, in regard to self-esteem, the project facilitated opportunities for participants to (a) capture their health and vitality with self-portraits, (b) celebrate their accomplishments and achievements, and (c) focus on putting themselves first.

Portraits of self-esteem: “I am the face of HIV today, a normal person”

Many women shared self-portraits. Often, women did this to share pride in their appearance – particularly in the context of living with HIV, which often invites negative stereotypes and visions of illness or sickness. For example, Roshona countered negative societal images with a picture of herself in which she believed she looked – like “any other person walking down the street.” She said, “I’m a person that looks like they do not have the virus, right?” Rubi also used the camera to depict that she did not “look like she had HIV.” While describing her self-portraits, she said, “[I am] the face of HIV today, a normal person. I call myself the diva … Just because you [have] HIV does not mean you are a death sentence.”

Similarly, other women wanted to express pride in their appearances and health despite how HIV may have defined them in the past. For example, Adele, who focused many of her project discussions on the transition she made from being “weak” and fearful of dying of HIV to living healthily, said that the very first picture she took with the camera was of “… me, looking in the mirror to [show] how hard I work [to stay healthy] and how beautiful I [am].” Likewise, Darlene photographed her transition to health with two self-portraits – a photograph of herself surrounded by dying plants, and a picture of herself surrounded by plants and flowers that were vibrant and thriving. She explained that she felt “wilted” and “dying” when she learned about having HIV, but slowly brought herself back to life. She said that viewing this transition made her feel “great” and “proud of herself” and the change.

For other women, photographing themselves was a way to show that they felt good about living openly with HIV. For instance, Yasmine took a picture of a photograph of herself featured on the front page of a local newspaper. She explained proudly that the picture “means the struggle’s over and I don’t have a problem putting my name to nothing.” She described her transformation from hiding her status to living fearlessly with HIV as a journey from “a tight ball to a little flower”, and commented that her newspaper feature showed “How far I came…Wow…Look at me now. I’m still here… Full of life.” She also said that photographing herself remained an important part of her daily routine, beyond the project: “I still take pictures. It is a daily routine for me now. I get up every morning, get myself together, tell myself how much I love myself, take a picture of me – every morning.”

Awards and accomplishments: “Wall of fame”

For Adele, Ella, Tierra, and Bobbi, among others, capturing and sharing representations of their accomplishments or ways that they met their goals, built or reinforced their self-esteem. For instance, Adele explained that at one point in her illness with HIV, she did not leave her house for 3 consecutive years. Thus, a photograph of an award that she received for taking HIV education classes was an important representation of the pride that she felt in her ability to persevere, and continue to learn and grow. Ella shared a picture of her college, explaining that to receive her diploma she surpassed numerous challenges including illness, familial care-taking responsibilities, and limited transportation options – sometimes even arriving to class without a way home. She said, “Seeing that picture of my school, seeing that picture of [friend who died who motivated her to go to school]… You have to keep going toward the mark.”

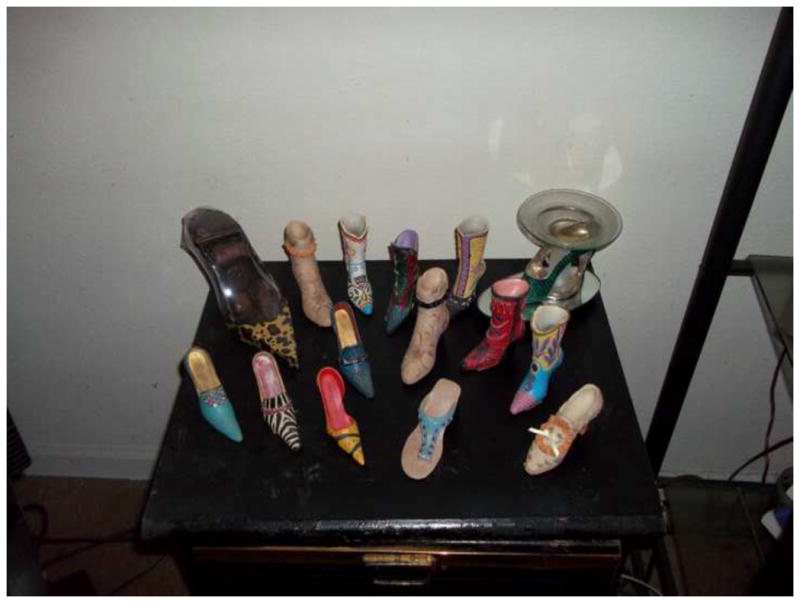

Tierra shared her “little shoe collection” to show her “step by step process” to achieving her goals. She elaborated, “every time I achieve an accomplishment or a goal, I buy me a shoe” (Figure 1). One of her most noteworthy achievements was improving her housing over time. She expressed this through pictures of the different houses that she lived in, each one an improvement over the last, and commented, “[This series of pictures] felt really good because of all of my accomplishments.” Similarly, Bobbi took a picture of every certificate or award that she ever received and hung them on a wall, calling the collection her “wall of fame.” She also described the photo as her defiant response to a television anti-drug campaign that alluded that drugs permanently destroyed users’ brains. She was a drug user and explained that these ads made her feel incompetent. She wanted her “wall” to show that she could still do something with her life despite that she had used drugs.

Figure 1.

Little shoe collection.

Putting themselves first: “It’s about me”

Taking and sharing pictures was also a way for the women to put themselves first, and by doing that, they felt better about themselves. When asked to describe how she chose what to photograph, Carlotta said that she aimed to make the project “about me.” Participants made the project about them by photographing special aspects of their lives including objects or activities that defined them. For example, Maureen took a picture of her Christmas tree, or “the chick tree,” and explained:

It’s a blue tree with purple and silver and green ornaments and it’s all mine - doesn’t have anything to do with anybody else or what anybody else wants. It’s all mine. That’s the first time I ever put up a Christmas tree for me… I always do things to please other people --make them happy, the colors they like. This is the first time that I got something for me. It is what I wanted.

Camille also said that the process helped her take time to put her own experiences before others, “All my life has consisted of is work and caring for my kids. I never did anything for myself. To take time and breathe, see something that I like and capture it [with the camera] – that meant a lot to me.” Debra described PNP as the first time that she told her story with HIV. She said that HIV had always made her feel different, but that she was beginning to come to terms with that feeling and said that the pictures helped her realize that it was okay and even “special” to be different.

Through pictures and stories about themselves, their achievements, or the ways that they prioritized themselves, the women developed or strengthened their self-esteem and sense of self-worth. This process was often an act of resistance to negative societal assumptions about women’s ability to thrive with HIV or despite unhealthy circumstances in their own pasts that jeopardized their well-being.

Confidence

In addition to enhancing self-esteem, the women also described how PNP improved their confidence. This included (a) facilitating the belief that they could do anything, and (b) helping participants realize their strengths.

Feeling capable: “There’s nothing that I can’t do”

When asked to identify the most important thing that they learned about themselves through the project, many women responded that they learned that they could do anything. For instance, Rubi’s pictures captured her commitment to living a healthy, long, and productive life. When reviewing pictures of her medicines, her support system, and a jar of condoms – Rubi said that her photos gave the message that, “[People living with HIV] can do anything they want to do and be what they want to be.” Adele said her pictures sent a similar message, although her images focused more on her own progress. She explained “There’s nothing that I can’t do … I don’t give up no matter what,” as she described a photo of a t-shirt that she carried around in a backpack with her all of the time that read, “We > AIDS” (We > AIDS, 2012):

They gave me 3 to 6 months…The doc gave up on me. [But] I’m still here. I weighed 35 pounds when I got out of hospice – 35 pounds. That’s why they probably counted me out. They carried me around like a baby, until I started getting up, trying to walk. [Then] they gave me a cane and from then on, I threw the cane away until I was running. And I’m still running.

Recognizing their strengths: “There is something about HIV that makes you a survivor”

The participants also reported that taking part in the project helped them realize their strengths. Maureen said that the process of taking pictures and recounting life experiences “reinforced that it doesn’t matter where you are at in this fight, that there is something about HIV that makes you a survivor.” The pictures helped the women identify different aspects of their lives that they might not have even noticed before. For example, Maureen recognized that she faced and managed multiple challenges effectively through her images, such as HIV-related depression, neuropathy, a sexual addiction that “brought her here [led to acquiring HIV],” and the importance of putting herself and her own needs first in relationships. Her pictures told a story about how she confronted and addressed these challenges over time. Similarly, Carlotta took a picture of a long and winding road – an analogy for her “journey to recovery” and good health. She discussed how “taking a picture and being able to write something on it” gave her strength because “It lets you know where you came from and where you are going.”

Other participants recognized their internal strengths in creative ways through the photos. Tara indicated that she had lived with HIV for 22 years but “never really patted myself on the back for going through the trials and tribulations. So this made me realize I’m a much stronger person all around.” She described her journey with HIV as one that moved from denial, to establishing a firm will to live. She took a picture of a sunflower to show that “I became a strong sunflower. And sunflowers don’t last forever. They die, but then new ones come to life.” Tasha took a picture of an electrical pole that looked like a tree. She described the pole as “prickly on the outside, but strong and firm on the inside.” She said that this was a metaphor for how she handled her problems. She explained that sometimes she felt defensive or depressed (prickly) but remained strong inside: “I know I’m a strong Black woman in the end … I fight [the depression] off in the end.” Debra described how she recognized her strength with two pictures of fountain statues. The first statue had crutches, which represented how she felt when she was first diagnosed. She said that she was infected unknowingly by her husband, which devastated and immobilized her. The second statue was dancing - without crutches. She indicated that this captured the way she regained strength to keep living: “I’m dancing and life is good…I don’t need the crutches. Crutches are gone” (Figure 2). In many of these examples –the sunflower, the pole, and the statues – women identified the ways that they were strong in concrete ways, often for the first time.

Figure 2.

Life is good.

Critical Thinking

Developing new or different critical perspectives on their experiences accompanied women’s enhanced self-esteem and increased confidence. Examples of such critical thinking skills centered around: (a) obtaining new perspectives on HIV, (b) gaining new insights on their challenges, and (c) envisioning new possibilities for their lives.

Seeing HIV in new ways: “A different vision on life”

Several women commented that the project helped them gain a new perspective on life with HIV. For example, Tina, who described herself as a very private person when the project began, said that PNP “helped me get a different vision of life [versus] just that tunnel and not expanding … it helped me spread out more.” As a result of the project, she began to see herself in a different light – as someone who could be more open with others about her experiences with HIV. Toni also focused most of her photographs on the struggle of hiding her HIV status and how to “come alive” despite the fear and stigma associated with living with HIV. She believed that the project “opens your eyes to what is really going on with yourself and HIV and looking closer at how it really affects you. It really puts a microscope on what’s really going on.” Her photographs helped her realize that she wanted to be more open about her HIV status with others and could work toward that. For several women, new perspectives included seeing the beauty or blessings in everyday life – something that they did not notice as much prior to PNP. For example, Paula said that the project revealed “the beauty of other worlds…Through everything that has happened to me, that’s what I’m trying to find – the beauty. Because I know there are some beautiful things.” Raquel described taking a picture of the sunset: The picture helped her to reflect on the importance of gratitude in her life:

The sun was up in the sky which was so pretty…And I just thought “What a blessing.” One thing people don’t understand about pictures is that you can never get rid of them. You’ll forget something and you’ll see a picture and “Wow, I’m back there again”… We really take the little things for granted. Like the sunset – you just think that you’re going to get up every morning. You’re going to see another sunset. Really, it’s not promised to you.

Gaining new insights on challenges: “I learned that I don’t delve deep enough into my HIV issues”

Participants also described gaining new insights about their challenges through taking and sharing their pictures. Melodie reflected on being infected unknowingly by her boyfriend while she showed the group a picture of court letters and documents, which summarized her efforts to hold him legally responsible. She noted that PNP helped her to “see what I was going through … because sometimes in life we don’t know what we are going through and we don’t see it, until we see it [literally – in pictures].” She described seeing her situation in a new way through the pictures:

[Taking pictures] helped me to see things that I didn’t want to see, or that I really didn’t pay attention to… [The pictures were] a constant reminder that you have to take care of yourself. You got to keep asking questions…With the letters, this person that I cared for so much put us in this situation. It hurt because I cared for this person. And I thought that [he] cared for me.

Raquel thought about a picture that she took of an ambulance, and said, “When I got the camera, I focused on everything more.” At one point, she had been riding in that ambulance regularly, an everyday event. Until she took the picture, she had not realized that she was healthier. It helped her to stop and take notice of what she had been doing and how it helped her to become healthier. Maureen also reflected on how the project helped her think differently about her health and living with her physical disability – HIV related neuropathy. She said that after living with HIV for so long, she got “complacent” and did not process her feelings about her health as much as she should or wanted to.

I learned that I don’t delve deep enough into my HIV issues…as like a way to protect myself more than anything. So, for me, the challenge [in the project] was to be honest… [For example through my pictures] I was able to really say, I’m disabled. As much as it bothers me, and as much as I try and fight it, the reality is that is the truth. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

I’m disabled.

By taking and discussing this picture, Maureen came to greater terms with being disabled, and also admitted that it hurt her when others did not understand the impact of her HIV and her disability on her life. The neuropathy caused her great pain, but because it was not a visible disability, others tended to dismiss her experiences.

Picturing new possibilities: “Reconstruction”

Thinking and reflecting critically about their lives helped several women to envision new possibilities for themselves and new solutions to their challenges. Alysha explained how taking pictures specifically helped women see different versions of themselves. She explained:

[The participants] can change their own selves by looking at their pictures and saying, “Okay, this picture is this way. This is how I used to be. Maybe next time I take a picture, it’ll be a little better picture, or it’ll be a little nicer, or something. Or – maybe I have to change this [issue photographed] for myself. I can do this.”

Many other women captured these new possibilities with photographs of transitions from illness or helplessness to vitality and hope. For example, Adele shared a picture of her church, under construction. She compared the church to herself and said that she could “also be rebuilt” into someone stronger and healthier. Similarly, Sharnelle photographed a restaurant that had burned down, and noted that like her and other WLH, it could be rebuilt.

Sometimes we feel like with HIV or any other chronic illness that we were burnt down. But in the end, this will be rebuilt into something. I’m at a place in my life where I want to be resurrected … I’m in a place where I want to release a lot of stuff, a lot of anger, a lot of hurt, a lot of pain - my daughter’s father, the stupid guys that I’ve even talked to, the hurt behind relationships, growing up in a single-parent household. I want to let that go, so I can move forward and become a better-looking [restaurant]. I will call this “Reconstruction.”

Taking Control

Beyond experiencing improved self-esteem, confidence, and critical thinking abilities, participants also expressed a greater sense of control over HIV. They also talked about getting control over specific challenges in their lives as a result of PNP.

Assuming control over HIV: “HIV doesn’t have me”

Through their photographs and discussions, the women expressed clearly that they were in control of their HIV. For example, Raquel reflected on what she learned about herself through the project and said, “Every morning I get up and look in the mirror and I’m looking at HIV…but it’s a part of me. It’s not me - it’s a part of me.” Similarly, Yasmine proudly shared a picture of herself in a newspaper article about HIV and clarified that, “HIV has been living with me for almost 18 years… I am not living with HIV.” When asked what she learned about herself through the project, Deedra also remarked, “[HIV] is not going to take control of me. I’m not going to let it control my life.” Maureen explained how taking pictures helped her to realize that she wanted to move beyond HIV to focus on other aspects of her life:

There are a lot of pictures that I didn’t take, but when I think about it – I want to go to school and take a picture. To me, that’s the beginning of the rest of my life. I’m there now. I’m not HIV anymore. It’s not my everything. It is part of me and it’s becoming kind of more in the background of my life.

As Tara shared pictures of her transition to accepting and “controlling” HIV, she explained that:

All those years of living in denial…As much as I was trying to deny HIV, it had total control over me. It controlled my every move, from the moment I woke up to the moment I went to sleep, it controlled me…It wasn’t until [I admitted] “this is what I am”… Now I’m controlling it.

Controlling and changing specific challenges: Action versus “running into a brick wall all the time”

Some women used their pictures to take control of and even address specific challenges in their lives. For example, Alysha gained control over a traumatic event in her life through the project. She told the group a devastating story about losing her 8-year-old daughter in a fire. She displayed a series of pictures of her family, including pictures of photographs of her deceased daughter. She said that participating in PNP helped her to process her daughter’s death and to manage her emotions about the event. When she shared the photo of her deceased daughter, Alysha said that she realized that she could “talk about things – I don’t have to hold [my feelings] in so long. I can talk about things and not be afraid.” She reflected on all of her pictures and how they helped her to feel in control of this tragedy:

[PNP] made me focus on what I can do instead of running into a brick wall all the time. It let me focus and gave me courage… It gives me a positive thought about things I can do in my life and not be down and out and stressed and depressed.

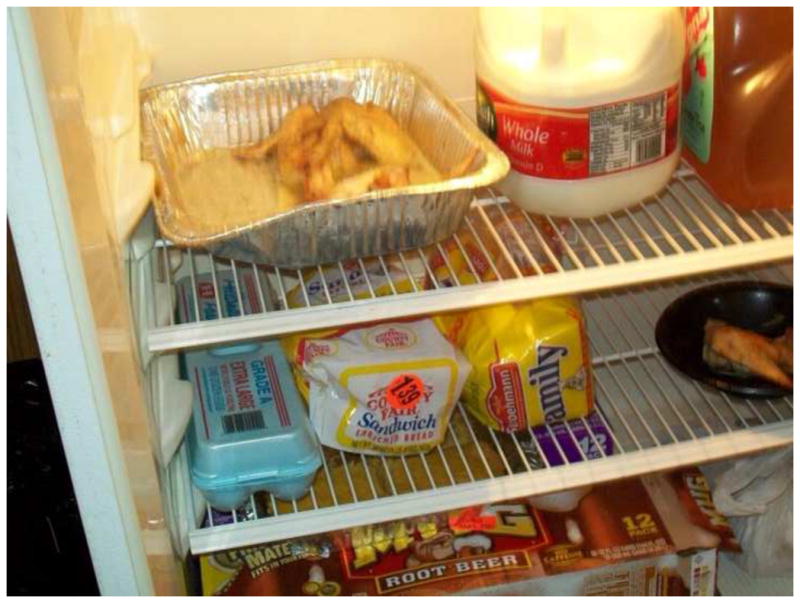

Bobbi took pictures to take control of her poor housing situation. Her apartment lacked basic features, like a refrigerator. She explained how she added one by dragging it to her house, by herself, from a dumpster (Figure 4), “I drug the refrigerator to the house by myself, ‘cause … I’m looking to see what I can use to make my house better.” In fact, she shared her pictures with church members, who helped her to secure a new refrigerator (Figure 5). Bobbi called the new refrigerator a “victory” and a “triumph,” but acknowledged that it did not resolve her larger housing issues. At the community photo exhibit (2 months after the project group sessions ended), Bobbi reported that members of her church also helped her move to better housing – showing that she could use the pictures to help take control of and resolve her housing challenges.

Figure 4.

From the dumpster.

Figure 5.

Triumph.

Many participants identified HIV stigma and discrimination as a major challenge in their lives. Several women described how PNP helped them to manage this stigma more effectively. For example, Sheila explained that her family did not accept her or her illness. She took pictures of two doors, one open and one closed, to explain how her approach on HIV stigma changed throughout the project.

The closed door – I was behind it for a long time before I told anybody. Then with the open door, you know, it brought out everything. I got to the point where I wanted everybody to know that needed to know…The [pictures] gave me a whole new experience because in the beginning I didn’t want to tell nobody…[the doors were] a new way to open up and let people know.

Like many other participants, Sheila focused on challenges using the camera, and drew strength from the group discussions to address the challenge directly.

Discussion

We explored the process of empowerment through photovoice with WLH who participated in the Picturing New Possibilities (PNP) project. The process included four key empowerment experiences: enhanced self-esteem – including recognition of one’s value and health, accomplishments, and the importance of self-prioritization; increased confidence and realization of one’s strengths; improved critical thinking skills such as new perspectives and insights; and more control over HIV and life challenges. Often, PNP facilitated a process that reinforced these experiences, or helped women to access internal resources that they already had, but did not realize were available to them.

Wang and Burris ‘(1994) classic description of photovoice and the individual empowerment process of self-development, problem analysis, and change skills, served as a general framework for our analysis. Our participants’ narratives provided details as to what those processes actually meant in their own lives. For instance, self-development was evident when women gained or refocused on a healthy vision of themselves, and their strengths and capabilities. Critical thinking skills – such as the ability to look at themselves or challenges in new ways, formed the basis of problem analysis. The women developed change skills as they identified strengths and abilities to solve problems, developed critical thinking skills to address problems in new ways, and asserted control over identified difficulties.

Our findings contribute to a small but growing understanding of the empowerment process that occurs as a result of photovoice. Duffy (2011) asked four single mothers who participated in a photovoice project what empowerment meant to them. Participants cited more control, confidence, life purpose, and ability to reach out to others, and rated their levels of empowerment as considerably higher than when they started the project. Foster-Fishman and colleagues (2005) explored the impact of participating in photovoice with 16 low-income youth and adults, who reported self-competence, critical awareness of their environments, and the cultivation of resources for social action. Carlson et al. (2006) explored how photovoice facilitated active participation in a community-academic partnership among low income, urban African Americans participating in two photovoice workshops. They described a process of critical consciousness-raising that progressed from passive adaptation or apathy and helplessness regarding life circumstances to emotional engagement, cognitive awakening, and intentions to solve problems. Our findings build on existing research by exploring empowerment concepts specifically, with a sizable group of women, and with in-depth qualitative methods.

PNP is also one of the few photovoice processes to be conducted exclusively with WLH (Gosselink & Myllykangas, 2007) and, to our knowledge, the only one that has explored the empowerment process in detail from the perspective of WLH’s experiences. Our participants’ empowerment was tied closely to their experiences of living with HIV. For example, the visual nature of the pictures created or reinforced the women’s pride in their health status and appearance – in spite of HIV. Self-portraits, in which the women looked healthy, beautiful, or like a “diva” became a way for, the women to resist the societal death sentence imposed on them by stereotypes of what the face of HIV looks like. The photos helped the women negotiate a sense of personhood that redefined them as resilient and awakened the power to resist negative images. Experiences of self-esteem also included pride about transformations from secrecy to living fearlessly with HIV – such as when Yasmine shared her picture in the newspaper.

The women’s experiences building or awakening their strengths also incorporated a transition from dying of, to living with, HIV. For example, Adele’s account of going from a 35-pound woman who needed to be carried around “like a baby” to “running” was closely tied to the challenges of living with HIV. In fact she shared the message about being “greater” than AIDS in her photograph that explored these issues. Capturing or reflecting on strengths in photos also helped women name their strengths and take on identities that they did not recognize prior to the project, such as being a survivor with HIV, or a person worthy of credit for enduring and thriving with HIV for many years.

Similarly, critical thinking included mental reorganization around priorities and a new appreciation for life amid HIV. For example, Raquel’s photo of the sunset was a reflection on “taking the little things for granted.” The women learned to appreciate beauty in their everyday lives in new ways. Critical thinking also included sharpened analytical skills, and helped the women to realize that their analyses were valuable. Images and discussions of images gave the women concrete evidence of daily difficulties, and helped them to better understand what was making them angry, upset, or depressed. In this way they gained more control over these challenges. For example, Melodie indicated that the process of self-awareness and discovery helped her to process her anger over being infected by her boyfriend, and prompted her to ask more questions to protect her health in future relationships. Another integral part of control for participants was taking control over HIV specifically and changing the internalized societal and medical dialogue to counter the notion that they were infected with HIV to “I have HIV but HIV does not have me.” Some participants even wanted to capture pictures of things important in their lives other than HIV – to show that HIV was moving to the “background” of their lives – like going to school.

These findings contribute to a growing body of literature that has defined photovoice as an effective tool to understand and address various health experiences and issues in underserved communities and to position community members as experts on the health issues that affect their lives (Catalani & Minkler, 2010). Beyond a needs assessment tool, our findings also support existing findings that have indicated that photovoice can enhance oppressed and vulnerable people’s recognition of their strengths and capabilities, thus facilitating empowerment and granting them more control over their lives and challenges. Identifying unique aspects of the photovoice empowerment process for WLH can enhance our understanding of how to improve the quality of life of WLH, through photovoice or other empowerment endeavors. The literature on the lack of definitional clarity of empowerment is extensive (Cattaneo & Chapman, 2010; Israel, Checkoway, Schulz, & Zimmerman, 1994; Rappaport, 1984; Wallerstein, 1992) and has explained diversity in the operationalization of the term, including empowerment as a process, an outcome, individual/psychological change, knowledge or skill acquisition, community change, organizational change, social or political action process, increased resources, and capacity to change macro-level inequities such as poverty or sexism. The importance of measuring empowerment notwithstanding, we do not aim to clarify the definitional debate here, but instead to clarify the process by which photovoice empowered one population - WLH – and build the information necessary to replicate the process for the benefit of women.

Our study was subject to several limitations. The aims of the study were to understand empowerment experiences of one group of women – the majority of whom identified as urban, low-income, African American, WLH. The findings cannot be generalized to all WLH. Moreover, to participate in PNP, WLH needed to be willing to share their experiences with other women and open to (i.e., it was not required) participating in a public exhibit. We did not include women who were not open about their HIV status or who may have feared participating in the project. Lastly, we conducted individual interviews with women at two project sites, but not at all sites. When we started the project we assumed that the group sessions would capture adequate information about women’s experiences, but we learned that the women wanted and needed more one-on-one opportunities to fully express themselves. Conducting interviews with all participants may have generated even more information about women’s individual empowerment experiences.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings make important contributions to the understanding of the empowerment experience of WLH who take part in photovoice projects and have key implications for research and practice. It is important for future qualitative and quantitative research to provide more information about the experiences of WLH who participate in photovoice, the meaning of empowerment to WLH, the association between empowerment and specific health outcomes, and if the empowerment framework that we found in our analysis – self-esteem, confidence, critical thinking, and control – will play out consistently in larger groups of WLH. Photovoice is a valuable tool. It is often applauded for its flexibility but most often used solely as a needs assessment research method (Catalani & Minkler, 2010).

Photovoice is a vitally important process for WLH, far beyond its research capabilities. Our findings indicated it was a potential way to address issues of self-esteem, confidence, control, and action among WLH. By giving women the opportunity to pose and answer questions about their lives, photovoice allowed the women in our study to awaken their powers of control over the issues and challenges raised. The women developed concrete and creative ways to build or access internal strengths and use these resources to motivate necessary change. Photovoice also offered sustainability by giving the women a tangible resource – a camera – that they could continue to use in their daily lives. As Yasmine explained, she still takes pictures, every morning, to capture her beauty and how much she values herself. That kind of consistent confirmation and power is essential for WLH, as their lives and experiences evolve, to reframe HIV, concentrate on how they can survive, address their challenges, improve the quality of their lives, and focus powerfully on the positive aspects of their journeys.

Key Considerations.

Many women living with HIV (WLH) are marginalized and face significant challenges to their well-being; tools to facilitate women’s empowerment, such as photovoice, are an essential part of holistic and quality health and nursing care for WLH.

Empowerment enhances women’s quality of life and helps them live healthier and longer with HIV.

It is valuable for nurses to understand empowerment among WLH and have tools to facilitate empowerment, given nurses’ meaningful and close relationships with patients.

Photovoice is a simple and sustainable tool to enhance empowerment and quality of life, and it can be implemented in various clinical settings under nurses’ directions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of NIH grants R25 DA028567, R25 HD045810, and R25 MH067127 to facilitate the completion of the work described in this manuscript; and wish to thank the participants for sharing their stories; Tabasha Holloman and Jenne Massie for helping to facilitate the project sessions; and Cathy Schneider for helping to perform the data analysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement. The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be constructed as a conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michelle Teti, Department of Health Sciences, The University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Latrice Pichon, School of Public Health, The University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, USA.

Allison Kabel, Department of Health Sciences, The University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri, USA.

Rose Farnan, Truman Medical Center, Kansas City, Missouri, USA.

Diane Binson, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Coyne-Beasley T, Doherty I, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(5):616–623. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a500126334-200604150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson ED, Engebretson J, Chamberlain RM. Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research. 2006;16(6):836–852. doi: 10.1177/1049732306287525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RL, Gramling LF. Stigma: A health barrier for women with HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15(5):30–39. doi: 10.1177/10553290032619811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education and Behavior. 2010;37(3):424–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. 1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo LB, Chapman AR. The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist. 2010;65(7):646–659. doi: 10.1037/a0018854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among women. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/pdf/women.pdf.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, England: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy LR. “Step by step we are stronger”: Women’s empowerment through photovoice. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2011;28:105–116. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster-Fishman P, Nowell B, Deacon Z, Nievar MA, McCann P. Using methods that matter: The impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;36(3–4):275–291. doi: 10.1007/s10464-005-8626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the opressed. New York, NY: Continuum; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2007;8(2):178–198. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswick, Canada: Aldine Transactions; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselink CA, Myllykangas SA. The leisure experiences of older US women living with HIV/AIDS. Health Care for Women International. 2007;28(1):3–20. doi: 10.1080/07399330601001402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodder S, Justman J, Hughes J, Wang J, Haley D, Adimora AA, El-Sadr W. The HPTN 064 (ISIS Study)—HIV Incidence in women at risk for HIV: US. Paper presented at the 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Seattle. 2012. Mar, Retrieved from http://www.retroconference.org/2012b/Abstracts/43702.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Checkoway B, Schulz A, Zimmerman M. Health education and community empowerment: Conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):149–170. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Grebler T. Stress and poverty predictors of treatment adherence among people with low-literacy living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2010;72(8):810–816. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f01be3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Pals SL, Campsmith ML. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors among homeless and housed persons with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49(4):451–455. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818a652c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic Inquiry. London, England: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, Weiss DS. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(8):2091–2100. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport J. Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prevention in Human Services. 1984;3:1–7. doi: 10.1300/J293v03n02_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riley ED, Gandhi M, Hare C, Cohen J, Hwang S. Poverty, unstable housing, and HIV infection among women living in the United States. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2007;4(4):181–186. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti M, Bowleg L, Lloyd L. ‘Pain on top of pain, hurtness on top of hurtness’: Social discrimination, psychological well-being, and sexual risk among women living with HIV/AIDS. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2010;22(4):205–218. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2010.482412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: Implications for health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1992;6(3):197–205. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-6.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Womens Health. 1999;8(2):185–192. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;2(2):171–186. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Redwood-Jones YA. Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from Flint Photovoice. Health Education and Behavior. 2001;28(5):560–572. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We > AIDS. Together we are greater than AIDS. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.greaterthan.org/

- Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ, Mikhail I, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Saag M. HIV discrimination and the health of women living with HIV. Women & Health. 2007;46(2–3):99–112. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]