Abstract

Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) serves as a co-stimulatory receptor for human T cells by enhancing T cell receptor (TCR)-induced cytokine production and proliferation. However, it is unknown where signals from the TCR and TLR2 converge to enhance T cell activation. To address this gap, we examined changes in TCR-induced signaling following concurrent TLR2 activation in human T cells. Both proximal TCR-mediated signaling and early NFκB activation were not enhanced by TCR andTLR2 co-activation, potentially due to the association of TLR2 with TLR10. Instead, TLR2 co-induction did augment Akt and Erk1/Erk2 activation in human T cells. These findings demonstrate that TLR2 activates distinct signaling pathways in human T cells and suggest that alterations in expression of TLR2 co-receptors may contribute to aberrant T cell responses.

Keywords: T cell receptor signaling, TLR2 co-stimulation, human T cells, NFκB, Akt and Erk1/Erk2

1. Introduction

T cell activation is required for the formation of immune responses to pathogens. The association between the TCR expressed on T cells and its cognate peptide-MHC complex presented on antigen presenting cells (APCs) provides the primary activating signal for T cells. Upon TCR activation, the kinases Lck and Fyn phosphorylate immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) found in several chains of the TCR. The tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 is then recruited to these phosphorylated ITAMs, where it is activated by Lck and Fyn upon phosphorylation of tyrosine 319. The adapter proteins LAT and SLP-76 are two substrates for activated ZAP-70. Once phosphorylated, LAT and SLP-76 cooperate to form multi-protein signaling complexes that activate multiple effector proteins [1,2]. The kinases Akt and Erk1/Erk2 are activated downstream of the LAT complex and control T cell effector responses like survival, proliferation, and cytokine production [1,3,4]. Thus, the induction of these signaling pathways must be tightly regulated to prevent inappropriate T cell responses that are linked to multiple human diseases [5–9].

While TCR induction is required for T cell activation, the concurrent activation of co-stimulatory receptors is also needed for effective T cell responses to infection. Compared to naïve T cells, activated and memory T cells express distinct co-stimulatory receptors that control their function and differentiation [1,10]. One such receptor is TLR2, an immune sensor that recognizes conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns found in bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites, and some endogenous ligands [11–15]. Therefore, TLR2 induction by self-and non-self ligands may contribute to the development of human autoimmune and inflammatory diseases or cancer [15–17].

Several publications have demonstrated that TLR2 can directly potentiate TCR-induced effector functions. TLR2 activation in mouse CD8 T cells was shown to enhance their differentiation to effector and memory T cells in response to suboptimal TCR activation [18,19]. Moreover, the cytotoxic CD8 T cell response to tumor antigens was also enhanced by TLR2 induction [20,21]. Concurrent TLR2 stimulation also increased TCR-induced proliferation, survival, and cytokine production in purified mouse and human CD4 and CD8 T cells [19,21–29]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) repress effector T cell responses, and TLR2 ligation in these cells has been shown to transiently inhibit their suppressive function [26,30,31]. As such, TLR2 activation in multiple T cell subsets transiently potentiates effector T cell responses to pathogens.

Although it is clear that the direct stimulation of TLR2 on T cells enhances TCR-dependent functions, it is currently unknown where TCR and TLR2 signals merge to augment human T cell function. In other immune cells, TLR2 induction triggers Erk1/Erk2 and Akt activation [12,32]. TLR2 ligation also induces IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, a process that allows the canonical NFκB p50/p65 transcription factor to translocate to the nucleus and drive inflammatory responses [12,32]. TLR2 stimulation in mouse T cells promotes NFκB, Erk1/Erk2, and Akt activation [23,33]. Thus, TLR2 co-activation may enhance the function of these proteins to augment human T cell responses.

Using HuT78 T cells and human activated peripheral blood T cells (hAPBTs), we found that TCR and TLR2-induced signaling converged at the level of Erk1/Erk2 and Akt activation. Surprisingly, we did not observe changes in early NFκB activation after TLR2 ligation, and TLR2 activation did not augment TCR-mediated NFκB function in human T cells. This observation is likely because TLR2 associates with TLR10, which is expressed in humans but not mice. Together, our data demonstrate that TLR2 activates distinct signaling pathways to co-stimulate human T cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 HuT78 Growth and Stimulation

HuT78 T cells were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 in IMDM media (Gibco) supplemented with 20% FBS (Atlantic), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco), and 50 U/ml penicillin-50 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco). Cells were grown to a density of 2–5×105 cell/ml. For stimulations, cells were washed with RPMI 1640 media without supplements (Gibco) and resuspended at 5×107 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 without supplements. Cells were next treated with 2 μg/ml soluble anti-CD3 (clone OKT3, Biolegend) and 1μg/ml Pam3CSK4 (InvivoGen) alone or in combination for various times. Samples were lysed using a 4-fold excess of hot 2X lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM DDT, 2% SDS, and 20% glycerol), heated to 95°C for 4 minutes, and sonicated to reduce viscosity.

2.2 Human Peripheral blood T cell isolation and activation

Whole blood was collected from healthy donors between the ages of 18 and 55 by the DeGowin Blood Center staff in the University of Iowa’s Hospitals and Clinics. These donors provided written consent for their blood cells to be used in research studies conducted at the University of Iowa. This consent form has been approved and reviewed by the University of Iowa’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were removed from the blood products using leukocyte reduction system (LRS) cones [34]. These normally discarded LRS cones were used as the source of PBMCs in all experiments. Since the patients consented for their cells to be used in research and were completely de-identified, the studies described in this manuscript were exempt from a specific IRB approval. PBMCs were flushed from the LRS cones using PBS (Gibco) containing 2% FBS and 2 mM EDTA and were further purified by Ficoll density centrifugation. PBMCs were resuspended in complete RPMI media (RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin) and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were then removed and grown in complete RPMI containing 100 U/ml human recombinant IL-2 (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Human rIL-2 from Dr. Maurice Gately, Hoffman La Roche Inc [35]). hAPBTs were generated by culturing non-adherent PBMCs with magnetic Dynabeads (Invitrogen) coated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 (clone CD28.2, Biolegend) for 5–7 days.

2.3 hABPT stimulation and extraction of nuclear proteins

hAPBTs were generated as described above and were rested in complete RPMI without activating beads and IL-2 for 24 hours before use. Cells were then washed once in RPMI 1640 without supplements and resuspended at 1×108 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 without supplements. Cells were next treated on ice with 2 μg/ml anti-CD3 and 2 μg/ml anti-CD4 (clone RPT-A4, Biolegend) for 30 minutes. After warming cells to 37°C for 10 minutes, they were stimulated with 25 μg/ml anti-mouse IgG (Rockland International) in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4. hAPBTs were also stimulated with 200 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 1 μM ionomycin where indicated. To isolate nuclear proteins, hAPBTs were treated with cell lysis buffer (10mM HEPES pH 7.9, 10mM KCl, 0.2mM EDTA pH 8.0, 1mM DTT, and protease inhibitor (1X EDTA-free complete mini tablets dissolved in PBS, Roche)) on ice for 20 minutes. Triton X-100 (0.32% v/v) was then added to the cell suspension, and the samples were centrifuged for 2 minutes at 13,000 rpm to isolate the nuclear pellet. The nuclear fractions were next washed twice in cell lysis buffer and resuspended in ice-cold nuclear extraction buffer (20mM HEPES pH 7.9, 400mM NaCl, 2mM EDTA, 1mM DTT, and protease inhibitor). The samples were then incubated on ice for 40 minutes, centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. Protein concentrations in nuclear extracts were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific).

2.4 Immunoblotting

Samples (2×105 cell equivalents or 20 μg of protein from the nuclear extracts) were loaded onto 4–15% Criterion pre-cast polyacrylamide gels (Biorad) and separated by SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), and the membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in 5% milk-TBST (10 mM TRIS (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween20) or SEA Block (Thermo Scientific) diluted 1:1 in PBS. The membranes were then incubated for 1 hour with primary antibodies against Src pY416 (Cell Signaling #2101), LAT pY226 (clone J96-1238.58.93, BD Pharmigen), SLP-76 pY128 (clone J141-668.36.58, BD Pharmigen), ZAP-70 pY319 (Cell Signaling #2717), IκBα (Cell Signaling #9242), Akt pT308 (Cell Signaling #4056), Akt pS473 (clone 14-6, Invitrogen), Erk1&2 pY185/pT187 (Invitrogen), NFκB p50 (Millipore #06-886), NFκB p100/p52 (Cell Signaling #4882), or NFATc1 (clone 7A6, Santa Cruz). HRP- and IRDye 800CW- or IRDye 680-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch and Licor Biosciences, respectively) were diluted in the appropriate blocking buffer and incubated with the membranes for 30 minutes at room temperature. The immunoblots were visualized using a Fuji Imager or the Licor Odyssey Infrared Imager. We have found that some pan antibodies, such as those against LAT and SLP-76, do not fully cross-react with the phosphorylated forms of these proteins [36]. Therefore, membranes were stripped of their antibodies and reprobed using anti-actin (clone C4, Millipore) or anti-GAPDH (Millipore) to ensure equivalent protein loading. Membranes containing nuclear extracts were reprobed using anti-YY1 (clone H-10, Santa Cruz).

2.5 Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot exposures in the linear range were selected for quantification. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots was performed using the gel plotting macro of ImageJ or the Odyssey v3.0 software. The data were then normalized such that the timepoint with maximum anti-TCR phosphorylation was set to 100% and the TCR phosphorylation value at 0 minutes was equal to 0%. The data were normalized using the following formulas:

Normalized actin intensity = Raw actin intensity for the timepoint ÷ lowest actin intensity for all samples;

-

% of maximum anti-TCR phosphorylation = [{(Raw intensity for timepoint ÷ Normalized actin intensity for timepoint) − (Raw intensity of the 0 minute timepoint ÷ Normalized actin intensity for 0 minute timepoint)} ÷ {(Raw intensity for maximum anti-TCR timepoint ÷ Normalized actin intensity for maximum anti-TCR timepoint) − (Raw intensity of the 0 minute timepoint ÷ Normalized actin intensity for 0 minute timepoint)}] × 100%. The maximum anti-TCR phosphorylation timepoints are specified in the Figures.

The formula used to examine IκBα degradation was as follows, with the anti-TCR 0 minute timepoint set to 100%:

-

% IκBα expression = [(Raw intensity of the timepoint ÷ Normalized actin intensity the timepoint) ÷ (Raw intensity of the anti-TCR 0 minute timepoint ÷ Normalized actin intensity for the anti-TCR 0 minute timepoint)] × 100%.

For the nuclear extraction experiments, the data were normalized using the following formula with the unstimulated (US) sample set to 100%:

Normalized intensity = [(Intensity of the sample ÷ Intensity of YY1 for the sample) ÷ (Intensity of US ÷ Intensity of YY1 for US)] × 100%.

2.6 Cytokine and Chemokine Detection

HuT78 T cells or hAPBTs were washed with RPMI 1640 without supplements and resuspended at 1×106 cells/ml in complete RPMI. Cells (0.5×106 per sample) were then stimulated on 24-well plates coated with various doses of anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml Pam3CSK4 and/or 10 μg/ml P. gingivalis LPS (InvivoGen). After 24 hours, IL-2 protein concentration in the culture supernatants was measured by standard TMB ELISA. Absorbance at 450 nM was read by a spectrophotometric plate reader. HuT78 T cells were also stimulated with 1μg/ml anti-CD3 in the absence or presence of 1μg/ml Pam3CSK4. The presence of various cytokines and chemokines in the culture media was determined by a human 30-plex luminex assay as previously described [36].

2.7 Calcium influx

HuT78 T cells were washed twice with RPMI 1640 without phenol red (Gibco) and resuspended at 1×106 cells/ml. The cells were then treated with 5 μM Fluor4-AM (Invitrogen) and 1mM probenecid (Sigma) at 37°C for 45 minutes. After extensive washing with RPMI 1640 without phenol red, cells were resuspended at 1×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 without phenol red and treated with 1mM probenecid on ice for 15 minutes. Cells were then heated to 37°C for 5 minutes and stimulated with 10 μg/ml anti-CD3 and 1μg/ml Pam3CSK4 alone or in combination. The data were obtained using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. The live population of cells was gated using forward vs. side scatter and the kinetics of the increase in Fluor-4 fluorescence was calculated and plotted using Microsoft Excel.

2.8 Immunoprecipitations

30×106 HuT78 T cells or 80×106 hAPBTs were stimulated using 5μg/ml Pam3CSK4 for various times and lysed with IP lysis buffer (25 mM TRIS pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Brij 97, 0.5% n-Octyl-beta-D-glucopyranoside, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor) on ice for 20 minutes with occasional vortexing. The samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were removed and transferred to tubes containing 4 μg anti-TLR2 (clone TLR2.1, Biolegend) and 25 μl Protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz). The samples were rotated overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed several times with IP wash buffer (25 mM TRIS pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Brij 97, and 0.5% octyl glucoside) and then pelleted by centrifugation. Bound proteins were eluted using hot 2X lysis buffer, and samples were heated to 95°C for 4 minutes. Immunoblot analysis was performed as described above using anti-TLR1 (clone TLR1.136, Biolegend) and anti-TLR10 (clone 158C1114, Abcam). Blots were stripped and reprobed using anti-TLR2 to assess TLR2 pulldown.

2.9 Flow Cytometry

1×106 HuT78 T cells, Jurkat E6.1 cells, and hAPBTs were washed with FACS buffer (PBS with 10% FBS and 0.05% sodium azide) and resuspended to a concentration of 1×107 cells/ml in FACS buffer. The cells treated with an isotype control antibody or the indicated primary antibodies for 30 minutes on ice and then washed extensively with FACS buffer. The cells were resuspended at 1×107 cells/ml in FACS buffer prior to incubating on ice with PE-conjugated anti-mouse IgG for 30 minutes. The cells were again washed with FACS buffer and resuspended at 2×106 cells/ml in FACS buffer. Samples were collected using a Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer or an Accuri C6 flow cytometer. The data were analyzed using FlowJo or Cflow Plus software.

2.10 Luciferase Assays

The NFκB and NF-AT luciferase reporter plasmids were a kind gift from Dr. Gail Bishop (Department of Microbiology, University of Iowa). HuT78 T cells were grown as described above and 5×106 cells were transfected with 3 μg of the reporter plasmids using Nucleofector Kit R (Lonza) and the Amaxa eletroporation program V-001. Transfected cells were incubated in complete IMDM for 16 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The cells were then washed extensively with RPMI 1640 without supplements and resuspended in complete IMDM media at 4×105 cells/ml. 2×105 cells were then stimulated for 6–8 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 using 2 μg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3 with or without 1 μg/ml soluble Pam3CSK4 or for 6 hours with 200 nM PMA and 1 μM ionomyocin. Untreated cells served as a negative control. The cells were treated with 100 μl of 1X Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega) at room temperature and were placed at −80°C for 20 minutes to complete lysis. Samples were next thawed to room temperature followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 2 minutes at 4°C. The sample supernatants (50 μl) were then mixed with 50 μl of room temperature Reporter Assay Buffer (Promega) and vortexed for 30 seconds. Luciferase activity for each stimulation condition was measured in duplicate using a luminometer.

3. Results

3.1 TLR2 is expressed on human activated peripheral blood T cells and HuT78 T cells

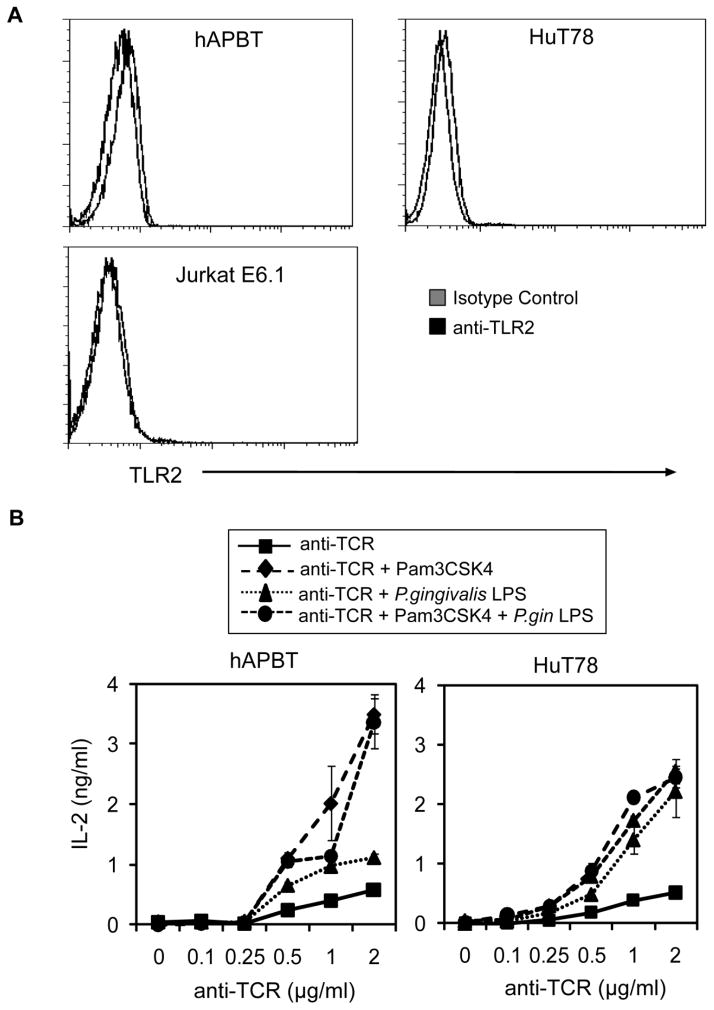

The goal of this study was to elucidate how TCR and TLR2-mediated signaling converge to synergistically enhance human T cell activation. Previous studies have shown that isolated human T cells express the mRNA for TLR2 [22,25,28,37], but only Komai-Koma et al. have examined the surface expression of the TLR2 protein on primary human T cells. No studies have characterized the surface expression of TLR2 on the widely-used human T cell lines, Jurkat E6.1 and HuT78. Therefore, TLR2 expression on these cells was examined by flow cytometry. We found that human activated peripheral blood T cells (hAPBTs) expressed low but detectable levels of TLR2 on their cell surfaces (Figure 1A), thus confirming that TLR2 is expressed in isolated human primary T cells [19,22,38]. We also found that TLR2 surface expression on HuT78 T cells was comparable to hAPBTs (Figure 1A: left and middle panels), while unstimulated Jurkat E6.1 cells did not express detectable levels of cell-surface TLR2 (Figure 1A: right panel). The weak surface expression of TLR2 on both APBTs and HuT78 T cells is consistent with previous studies that have shown that T cells express substantially lower levels of TLR2 mRNA than B cells, monocytes, and macrophages [37,39]. These results show that both hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells express relatively low levels of TLR2 protein on their cell surfaces and suggest that these cells are responsive to TLR2 ligands.

Figure 1. TLR2 is a co-stimulatory receptor for human APBTs and HuT78 cells.

(A) TLR2 surface expression in unstimulated Jurkat E6.1 cells (left panel), HuT78 T cells (middle panel), or hAPBTs (right panel) was examined by flow cytometry. (B) hAPBTs (left panel) or HuT78 cells (right panel) were stimulated for 24 hours with various doses of anti-CD3 in the absence or presence of the TLR2 ligands, PAM3CSK4 and/or P. gingivalis LPS. IL-2 in the culture supernatants was detected by ELISA.

3.2 TLR2 serves as co-stimulatory receptor for human T cells

Several reports have demonstrated that TLR2 acts as a co-stimulatory receptor for activated human T cells by enhancing TCR-mediated cytokine production [22,24–26,28,29,38]. Therefore, we stimulated HuT78 T cells and hAPBTs with two TLR2 ligands, Pam3CSK4 and P. gingivalis LPS, in the absence or presence of various doses of a stimulatory antibody specific for the TCR and then measured the production of IL-2 by ELISA. As expected, TCR activation alone promoted IL-2 production by hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells at concentrations greater than 0.5 μg/ml of anti-TCR (Figure 1B). When TCR activation was coupled with TLR2 stimulation, there was a marked 2–6 fold increase in IL-2 production by hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells over TCR induction alone (Figure 1B). For an unknown reason, P.gingivalis LPS was a less potent co-stimulatory agonist for hAPBTs than HuT78 T cells (Figure 1B). The effects of stimulating hAPBTs or HuT78 T cells with both Pam3CSK4 and P. gingivalis LPS in the presence of anti-TCR were not additive, likely because these ligands both promote cellular activation via TLR2 and TLR1 heterodimers [11]. Additionally, TLR2 co-stimulation enhanced the TCR-induced production of the cytokines IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-13, GM-CSF, and VEGF by 2–5 fold and augmented the TCR-mediated secretion of the chemokines CXCL10 and CCL5 by 2–3 fold (Table I). We found that TLR2 activation alone did not significantly induce the expression any cytokine or chemokine we examined except IL-10 (Table I). Together, these data reveal that TLR2 can modulate cytokine and chemokine production by hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells. They also demonstrate that HuT78 T cells are a useful model for studying TLR2 co-stimulatory function in human T cells.

Table I.

TLR2 activation alters cytokine and chemokine production by HuT78 T cells.

| Cytokine | No Treatment (pg/ml) | TCR (pg/ml) | TLR2 (pg/ml) | TCR & TLR2 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | N.D. | 990 ± 60 | N.D. | 4080 ± 40 |

| IL-7 | N.D. | 130 ± 30 | N.D. | 100 ± 40 |

| IL-10 | N.D. | 1370 ± 270 | 330 ± 0 | 3230 ± 300 |

| IL-13 | N.D. | 80 ± 5 | N.D. | 340 ± 10 |

| IFN-γ | N.D. | 30 ± 4 | N.D. | 90 ± 10 |

| VEGF | 120 ± 0 | 320 ± 60 | 150 ± 0 | 660 ± 20 |

| GM-CSF | N.D. | 350 ± 60 | N.D. | 1800 ± 260 |

| MIP-1α/CCL3 | N.D. | 90 ± 20 | N.D. | 130 ±10 |

| MIP-1β/CCL4 | N.D. | 120 ± 10 | N.D. | 160 ± 20 |

| IP-10/CXCL10 | 20 ± 0 | 70 ± 5 | 50 ± 0 | 220 ± 10 |

| MIG/CXCL9 | N.D. | 100 ± 20 | N.D. | 150 ± 0 |

| RANTES/CCL5 | 1120 ± 0 | 2860 ± 320 | 1080 ± 0 | 4550 ± 240 |

Cytokines and chemokines were detected by a human multiplex assay. Values are expressed as the average concentration ± SD of duplicate samples.

N.D. = not detected.

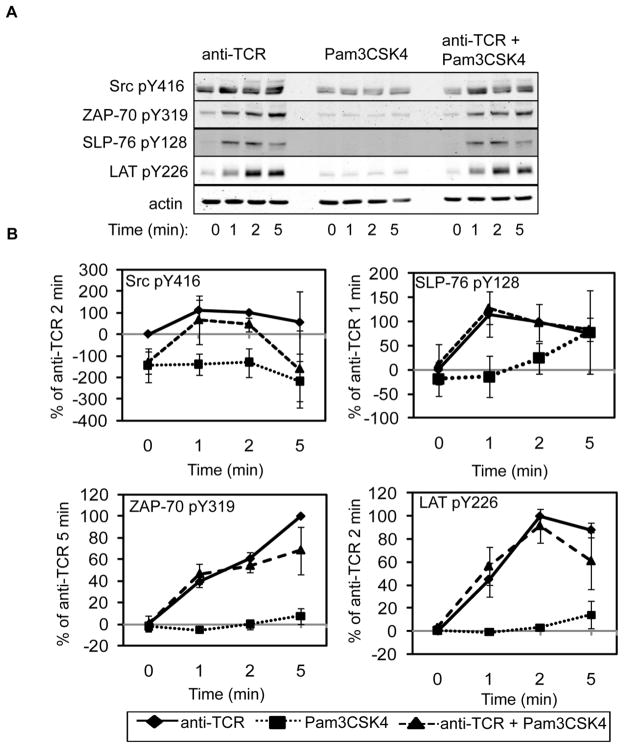

3.3 TLR2 co-activation does not affect early TCR-mediated signaling in HuT78 T cells

The data above demonstrate that TLR2 acts as a co-stimulatory receptor for both hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells. However, it is currently unknown what intracellular signaling pathways are enhanced following co-induction of the TCR and TLR2. To address these mechanisms, we stimulated human T cells with a soluble agonistic anti-TCR antibody and/or a TLR2 ligand and then performed quantitative immunoblotting to measure changes in the phosphorylation of TCR signaling proteins [36,40]. We have previously shown that proximal TCR-mediated signaling is comparable in hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells [36]. Since TLR2 activation also induced similar responses in hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells regardless of the TLR2 ligand used (Figure 1B), we elected to use HuT78 T cells and Pam3CSK4 as a TLR2 stimulus to examine the mechanisms for TLR2 co-stimulation.

It was possible that TLR2 co-induction increased the magnitude of early TCR signaling. We first examined whether TCR-induced Lck and Fyn activity were altered in response to TLR2 co-activation by immunoblotting for phosphorylated Src tyrosine 416, which cross-reacts with Lck and Fyn when they are phosphorylated on their activating residues. As shown in Figure 2, TCR stimulation alone induced a small increase in the phosphorylation of Src tyrosine 416, while TLR2 activation alone had no effect on the phosphorylation of Lck and Fyn. Co-activation of the TCR and TLR2 did not significantly alter the phosphorylation of Lck and Fyn when compared to TCR stimulation alone, suggesting that the activity of these kinases is not enhanced by TLR2 co-stimulation (Figure 2). Consistent with these data, the phosphorylation of ZAP-70 tyrosine 319, LAT tyrosine 226, and SLP-76 tyrosine 128 was also not enhanced by the concurrent stimulation of the TCR and TLR2 when compared to TCR activation alone (Figure 2). Collectively, these results demonstrate that TLR2 co-induction does not enhance early TCR-mediated signaling in human T cells.

Figure 2. TLR2 co-activation does not enhance early TCR-induced signaling in HuT78 cells.

(A) HuT78 T cells were stimulated for various times with soluble anti-CD3 and soluble PAM3CSK4 alone or in combination. Cellular lysates were resolved by PAGE and immunoblotting was used to examine the site specific phosphorylation of Lck/Fyn, ZAP-70, SLP-76, and LAT. Actin was used as a loading control. Data is representative of three independent experiments. (B) Average normalized results ± SEM for all three independent replicates are shown graphically.

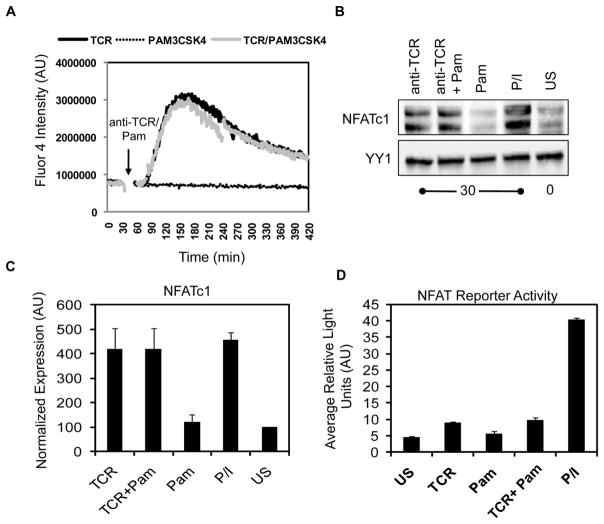

3.4 TLR2 co-stimulation does not alter TCR-induced Ca2+ influx or NFAT activation in human T cells

Previous studies have shown that the Tec family of tyrosine kinases are activated downstream of TLRs [41–43]. In T cells, the Tec kinases Itk and Rlk control TCR-induced calcium (Ca2+) influx and the subsequent activation the transcription factor NFAT [44–46]. Activated NFAT then translocates to the nucleus and promotes the release of cytokines [1,2]. Given these data, it was feasible that co-activation of TLR2 could potentiate TCR-mediated Ca2+ influx and NFAT activation, thereby enhancing T cell activation. To test this possibility, we treated HuT78 T cells with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluor4-AM and stimulated them with anti-TCR and/or Pam3CSK4. The influx of Ca2+ over time was then measured by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 3A, intracellular calcium concentrations rapidly increased after TCR activation, with levels peaking at 2–3 minutes and resolving by 8 minutes after stimulation. Interestingly, the magnitude and kinetics of Ca2+ influx were comparable in HuT78 T cells treated with both anti-TCR and Pam3CSK4. By contrast, TLR2 induction alone led to no detectable changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations (Figure 3A). We also found that the simultaneous activation of the TCR and TLR2 did not increase either NFATc1 nuclear translocation in hAPBTs (Figure 3B–C) or NFAT reporter activity in HuT78 T cells (Figure 3D) when compared to TCR activation alone. Together, these results demonstrate that TLR2 activation does not augment TCR-induced Ca2+ signaling in human T cells and further support the data showing that TLR2 co-stimulation does not enhance proximal TCR signaling that is driven by the activation of tyrosine kinases.

Figure 3. TCR-induced Ca2+ influx and NFAT activation are not increased by concurrent TLR2 stimulation in human T cells.

(A) HuT78 T cells were stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 and soluble PAM3CSK4 alone or in combination. Ca2+ influx over time was measured by flow cytometry. Data is representative of three independent experiments. (B) hAPBTs were stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 and anti-CD4, soluble PAM3CSK4, or all three stimuli for 30 minutes. Unstimulated APBTs and APBTs stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (P/I) for 30 minutes served as controls. Immunoblotting was used to detect NFATc1 and YY1 in nuclear extracts. Data is representative of three experiments. (C) Normalized nuclear NFATc1 expression was calculated and the mean ± SEM for all three independent replicates was graphed. (D) NFAT reporter activity was measured in HuT78 T cells stimulated for 8 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3, Pam3CSK4, or both stimuli. Cells stimulated with P/I for 6 hours served as a positive control. The graph shows the mean of duplicate samples ± SD, and the data are representative of three independent experiments.

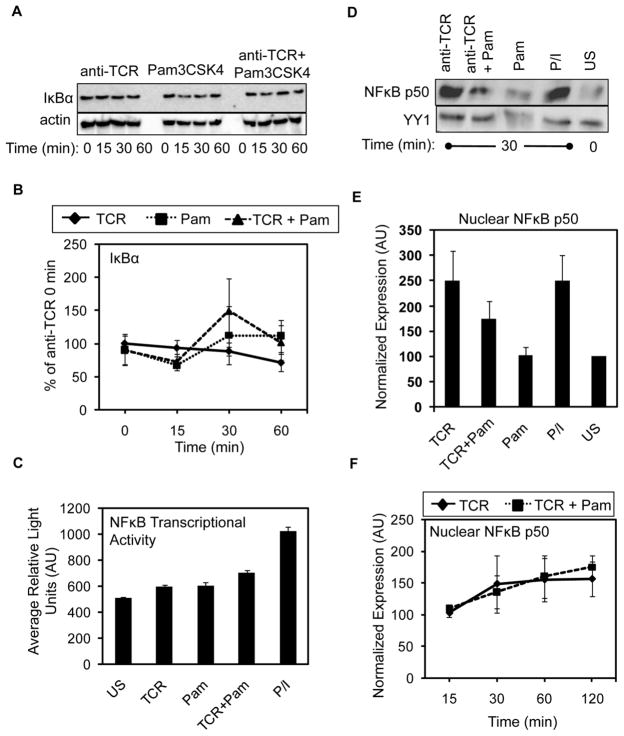

3.5 TLR2 signaling does not promote NFκB activation in human T cells

TCR stimulation weakly induces IκBα degradation, which promotes NFκB activity [1,2]. The induction of TLR2 in multiple immune cell types, including mouse T cells, also strongly activates NFκB [12,23,33]. These reports suggest that TLR2 co-stimulation may enhance TCR-mediated NFκB activity. To address this potential mechanism, we stimulated HuT78 T cells with anti-TCR and/or Pam3CSK4 for various times and quantified changes in IκBα expression. As expected, TCR induction alone led to a small but reproducible decrease in IκBα expression by 60 minutes after stimulation (Figure 4A–B). By contrast, IκBα protein levels were not significantly altered in HuT78 T cells after TLR2 stimulation. Surprisingly, the concurrent activation of the TCR and TLR2 also did not synergistically induce IκBα degradation in HuT78 T cells (Figure 4A–B). To verify that TLR2 signaling does not induce NFκB activity in HuT78 T cells, we used NFκB reporter assays. As shown in Figure 4C, NFκB-dependent luciferase activity was not strongly induced by anti-TCR or Pam3CSK4 stimulation, even when used in combination. As expected, PMA and ionomycin stimulation activated NFκB activity in these cells. These data suggest that TLR2 does not activate NFκB in HuT78 T cells, even when combined with TCR induction.

Figure 4. TCR-induced activation of the classical NFκB pathway is not increased upon simultaneousTLR2 engagement.

(A) HuT78 T cells were stimulated for various times as in Figure 2. The expression of IκBα and actin were analyzed by immunoblotting. Data is representative of three independent experiments. (B) Quantification of IκBα degradation is shown graphically as the average ± SEM for three independent replicates. (C) Luciferase activity in HuT78 cells stimulated with anti-CD3, Pam3CSK4, both, or PMA and ionomycin for 6 hours. Graph shows mean of duplicate samples ± SD and data are representative of three experiments. (D) APBTs were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD4, PAM3CSK4, or all three stimuli for 30 minutes. Control HuT78 T cells were not treated or were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (P/I). Nuclear extracts were probed for p50 and YY1 expression by immunoblotting. The data shown represents four independent experiments. (E) Average normalized nuclear p50 expression ± SEM for the four independent experiments was calculated and graphed. (F) APBTs were stimulated as in (D) for various times. NFκB p50 and YY1 expression in nuclear extracts were detected by immunoblotting. The mean nuclear p50 expression from three independent experiments ± SEM is shown.

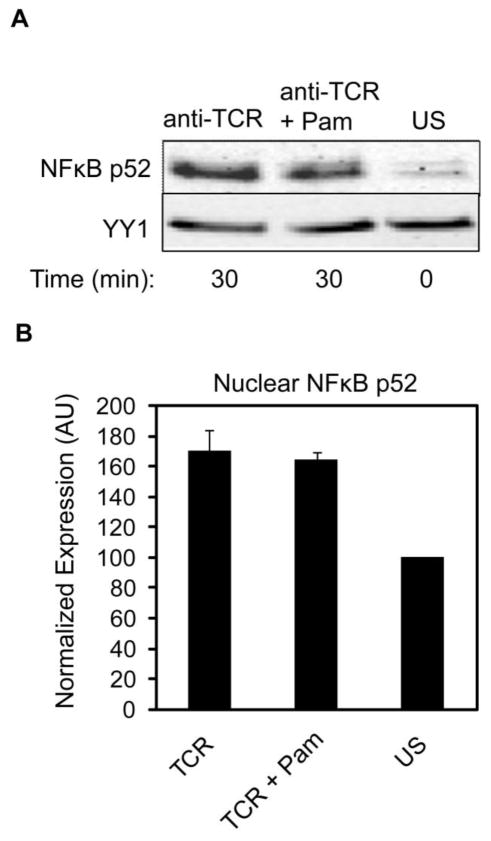

To confirm these results, we also quantified changes in NFκB activation in hAPBTs. We treated hAPBTs with anti-TCR or Pam3CSK4 alone or in combination for various times and then prepared nuclear extracts. The amount of NFκB p50 present in the nucleus was examined by immunoblotting, since activated NFκB translocates to the nucleus to bind to its target genes. The nuclear expression of NFκB p50 was significantly enhanced in cells stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (P/I) or anti-TCR for 30 minutes when compared to unstimulated hAPBTs (Figure 4D–E). In confirmation of our observations in HuT78 T cells, no changes in nuclear NFkB p50 levels were detected in cells stimulated with Pam3CSK4 alone. Additionally, TLR2 co-induction did not further increase the amount of NFκB p50 present in the nucleus at 30–120 minutes after stimulation when compared to TCR activation alone (Figure 4D–F). We also investigated if TLR2 could activate the alternative NFκB pathway in human T cells by examining the nuclear translocation of NFκB p52 in hAPBTs. As shown in Figure 5, the nuclear localization of NFκB p52 was slightly enhanced following TCR stimulation. However, the simultaneous activation of the TCR and TLR2 did not further increase the amount of NFκB p52 found in the nucleus. Collectively, these data suggest that TLR2 signaling does not activate either the classical or non-canonical NFκB pathways in human T cells. Furthermore, they demonstrate that TLR2 co-stimulation does not enhance TCR-induced NFκB activity in these cells.

Figure 5. TCR-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB p52 is not increased by TLR2 co-activation.

hAPBTs were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD4 and Pam3CSK4, alone or in combination, for 30 minutes. The expression of NFκB p52 and YY1 were detected in nuclear extracts by immunoblotting. Data is representative of three experiments. (B) Normalized average p52 translocation ± SEM from three independent replicates was calculated and graphed.

3.6 TLR2 associates with both TLR1 and TLR10 in human T cells

Our data suggest that TLR2 activation does not induce the transcriptional activity of NFκB, a result that was unexpected given that TLR2 induction has been reported to activate early NFκB signaling in primary mouse T cells [23,33]. Therefore, we next sought to elucidate why TLR2 stimulation does not activate NFκB in human T cells. Both mouse and human immune cells express the genes for TLRs 1, 2, and 6. However, only humans express a functional TLR10 protein, since TLR10 is a pseudogene in mice [11,47,48]. Recently, it was shown that triaceylated lipids like those found in Pam3CSK4 and P. gingivalis LPS bind to both human TLR1/TLR2 and TLR2/TLR10 heterodimers [11,49]. Interestingly, the signaling pathways activated downstream of the TLR2/TLR10 receptor differ from those induced by the TLR1/TLR2 pair, as the TLR2/TLR10 complex does not stimulate NFkB [11]. Therefore, we predicted that TLR2-induced signaling in human T cells may diverge from mouse T cells because TLR2 pairs with TLR10 in human T cells.

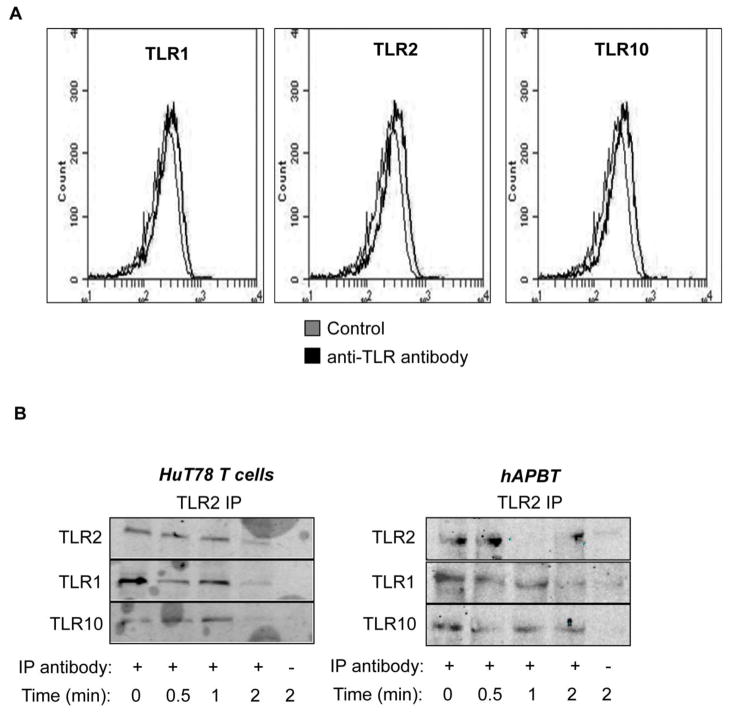

Human peripheral blood T cells have been reported to express low levels of TLR1 and TLR10 mRNA and protein [26, 28, 37, 39, 50, 51]; however, the surface expression of these TLRs has not been evaluated in HuT78 T cells. Therefore, HuT78 T cells were stained with saturating doses of antibodies against TLR1, TLR10, and TLR2 and their expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. Consistent with our earlier observations, TLR2 was expressed at low levels on HuT78 T cells (Figure 1A and Figure 6A). Further, we found that HuT78 T cells also weakly expressed both TLR1 and TLR10 (Figure 6A). These results suggest that TLR2 has the potential to dimerize with either TLR1 or TLR10 in hAPBTs and HuT78 T cells.

Figure 6. TLR2 complexes with both TLR1 and TLR10 in human T cells.

(A) Surface expression of LR1 (left panel), TLR2 (middle panel), and TLR10 (right panel) in HuT78 T cells was examined by flow cytometry. Data is representative of two independent experiments. (B) HuT78 T cells or hAPBTs were stimulated for various times with 5 μg/ml of Pam3CSK4. TLR2 was immunoprecipitated from HuT78 T cells (left) or from hAPBTs (right) with anti-TLR2. The amount of TLR1 and TLR10 associated with TLR2 was assessed by immunoblotting. Blots are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Next, HuT78 T cells or hAPBTs were stimulated with Pam3CSK4 for various times and TLR2 was immunoprecipitated from these cells. The amount of TLR1 and TLR10 complexed with TLR2 was examined by immunoblotting. Interestingly, we found that TLR2 interacts with both TLR1 and TLR10 in HuT78 T cells and hAPBTs (Figure 6B). Moreover, the formation of complexes containing TLR2, TLR10, and/or TLR1 appeared to occur independently of ligand binding, since these proteins associated in non-stimulated cells. Upon activation, TLR2 appeared to form a more stable interaction with TLR10 when compared to its association with TLR1 (Figure 6B). Our data show for the first time that HuT78 T cells express TLR1, TLR2, and TLR10 and that TLR2 and TLR10 associate in human T cells. When combined with our observation that NFκB activation is not altered (Figures 4–5), these results suggest that the TLR2/TLR10 heterodimer regulates TLR2 co-stimulatory signals that augment TCR-mediated cytokine and chemokine production in human T cells.

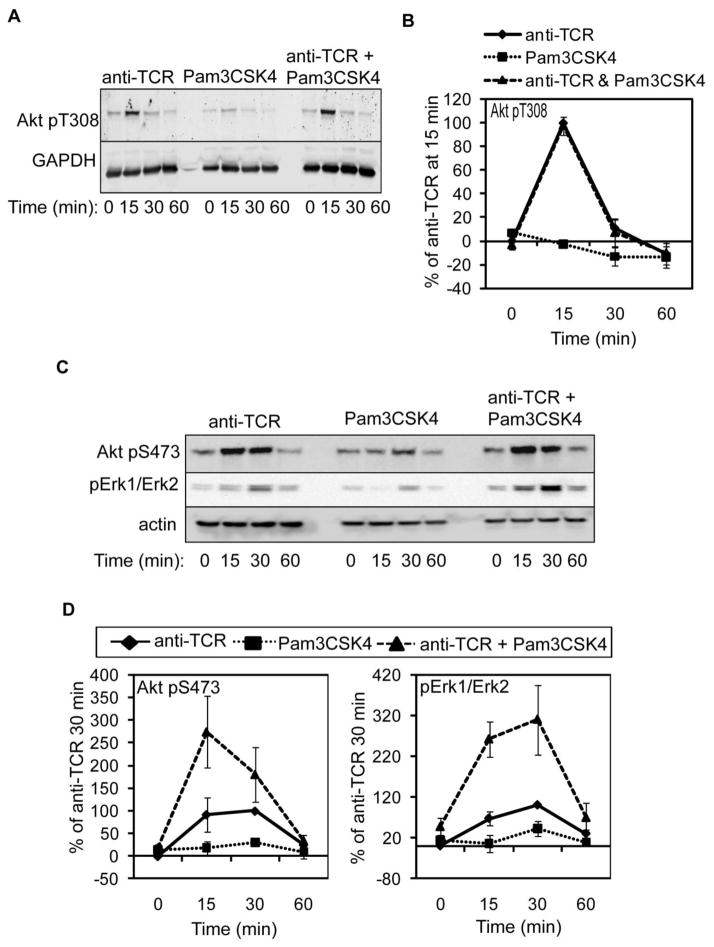

3.7 TCR-mediated Akt and Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation are enhanced by TLR2 co-engagement in HuT78 T cells

The serine/threonine kinases Akt and Erk1/Erk2 are phosphorylated upon TCR engagement [1,2]. TLR2 agonists independently activate Erk1/Erk2 in mouse T cells, and Pam3CSK4 treatment augments Akt phosphorylation in response to TCR engagement in these cells [18,23,33,52]. Therefore, we examined if TLR2 activation influences Akt and Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation both in the absence or presence of TCR engagement. To that end, HuT78 T cells were stimulated as above and Akt and Erk1/Erk2 activation were examined by immunoblotting. The phosphorylation of Akt on threonine 308 and serine 473 is required for maximum Akt function [53]. As shown in Figure 7A–7B, Akt threonine 308 phosphorylation was not induced by TLR2 stimulation alone nor was the TCR-mediated phosphorylation of this site enhanced by TLR2 co-stimulation. By contrast, stimulation of TLR2 alone was sufficient to modestly induce Akt serine 473 phosphorylation at 30 minutes post-stimulation (Figure 7C–7D). Further, co-induction of the TCR and TLR2 led to a 2-fold enhancement in Akt phosphorylation when compared to TCR stimulation alone at 15 minutes. We also found that Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation was detectable following Pam3CSK4 treatment alone. In the presence of the TLR2 agonist, the TCR-induced phosphorylation of Erk1/Erk2 was enhanced 3–4 fold over TCR activation alone (Figure 7C–7D). These results demonstrate that both Akt and Erk1/Erk2 activity are induced by TLR2. Furthermore, they show that TCR- and TLR2-induced signals converge to synergically enhance Akt and Erk1/Erk2 activation in human T cells.

Figure 7. TLR2 co-engagement augments TCR-mediated Akt and Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation in HuT78 cells.

HuT78 T cells were stimulated for various times as in Figure 2. (A) The phosphorylation of Akt threonine 308 and GAPDH expression or (C) Akt serine 473 and Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation and actin expression were detected by immunoblotting. A representative of three independent experiments is shown. (B and D) Results were normalized and the average of three independent replicates ± SEM was graphed.

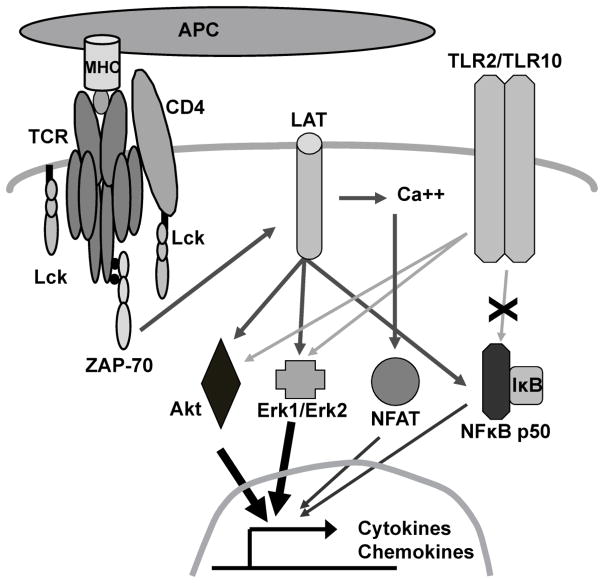

4. Discussion

In this study, we characterized the molecular events that control TLR2 co-stimulatory signals in human T cells. We found that the induction of proximal TCR signaling pathways and NFκB function were not enhanced by concurrent TLR2 activation. Instead, co-induction of the TCR and TLR2 significantly increased the site-specific phosphorylation of Akt and Erk1/Erk2 when compared to TCR activation alone (Figure 8). These findings are of therapeutic interest, since TLR2 not only plays a vital role in shaping T cell immunity to pathogens but also in the development of multiple human diseases [15,54–57].

Figure 8.

Proposed model for TLR2 co-stimulation in human T cells

TLR2 controls T cell activation by several mechanisms. First, TLR2 stimulation in APC leads to increased antigen presentation and enhanced co-stimulatory molecule expression [58]. When T cells make contact with these APC, the TCR and co-stimulatory receptors are activated. Thus, TLR2 can indirectly prime T cell responses by altering the function of APCs. In addition, TLR2 activation has been suggested to enhance T cell activation by directly suppressing Treg responses or altering their phenotype, although this function remains controversial [26,30,31]. Finally, we and others have demonstrated that TLR2 acts as a direct co-stimulatory receptor for human effector T cells. In agreement with previous data [22,24,25,28,29,38], we found that stimulating hAPBTs with TLR2 ligands synergically enhanced TCR-induced IL-2 and IFN-γ (Figure 1 and Tremblay and Houtman, manuscript submitted). We also showed for the first time that TLR2 acts as co-stimulatory receptor for HuT78 T cells, as the simultaneous activation of TLR2 enhanced multiple TCR-mediated cytokine and chemokines responses by these cells (Figure 1 and Table I). Together, these data suggest that TLR2 activation plays a multi-factorial role in priming T cell responses that control human disease.

We observed that TLR2 ligation alone promoted IL-10 secretion by HuT78 T cells (Table I), which has previously been observed in other immune cells [59,60]. IL-10 secretion by T cells is an important regulatory mechanism used to suppress their activation [61]. Therefore, when T cells are chronically exposed to TLR2 ligands, such as in mucosal sites or during sepsis, TLR2 activation may intrinsically inhibit their ability to produce highly inflammatory cytokines. In support of this idea, we recently found that TCR-induced IL-2 but not IFN-γ production was enhanced upon pre-treatment with Pam3CSK4 in human T cells (Tremblay and Houtman, manuscript submitted). These data may also explain, in part, why TLR2 is linked to inflammatory bowel disease and increased susceptibility to septic shock following infection with gram positive bacteria [62,63].

In contrast to observations made in mouse T cells [23,33], we found that TLR2 fails to activate the canonical NFκB pathway in human T cells (Figure 4). This was despite the fact that these studies all used TLR1/TLR2 ligands as a stimulus and both human and mouse T cells express TLR1 (Figure 6 and [23,26]). The distinct expression of the TLR2 co-receptor, TLR10, in these species may explain these differences, since humans express a functional TLR10 protein whereas mice express a non-functional psuedogene for TLR10 [11,47,48]. Our lab and others have shown that HuT78 T cells and human peripheral blood T cells express low levels TLR10 protein on their cell surfaces (Figure 6A and [26,51]). We also observed that TLR2 associated with both TLR1 and TLR10 in human T cells (Figure 6B). Interestingly, a recent study by Guan and co-workers [11] showed that the TLR1/TLR2 and TLR2/TLR10 receptors shared ligand specificity. Moreover, unlike the activated TLR1/TLR2 complex, stimulation of the TLR2/TLR10 receptor failed to induce NFκB reporter gene expression or to promote the release of NFκB-dependent cytokines [11]. These data strongly suggest that TLR2 co-stimulation in response to Pam3CSK4 or P. gingivalis LPS is controlled by the TLR2/TLR10 receptor in human T cells, even though these cells also express TLR1. We attempted to knock down TLR10 expression in HuT78 T cells to ascertain its role in TLR2 co-stimulation. However, we had difficulty verifying that its expression was decreased, since TLR10 is expressed at very low levels in human T cells. Therefore, we are still actively investigating the function of TLR10 in these cells.

The TCR-mediated phosphorylation Akt serine 473, but not Akt threonine 308, was enhanced following TLR2 co-activation (Figure 7). The phosphorylation of threonine 308 by PDK1 is required for Akt activation, while the phosphorylation on serine 473 induces maximum catalytic activity [53]. In T cells, Akt serine 473 phosphorylation is induced by mTORC2 or PKC-α [53,64]. Since mTORC2 and PKC-α are also activated downstream of TLRs [65,66], TCR and TLR2 signals may synergistically enhance the function of these kinases to augment Akt activation. DNA-PK also phosphorylates Akt serine 473 but not Akt threonine 308 in other cellular systems [67,68]. Increased c-AMP levels were shown to activate an EPAC/Rap2 signaling cascade that promoted DNA-PK translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Following this translocation, Akt serine 473 was phosphorylated [68]. Thus, a similar pathway may also induce the selective phosphorylation of Akt serine 473 downstream of TLR2, thereby potentiating the TCR-induced function of Akt.

In addition to increased Akt function, we found that TLR2 stimulation alone or in combination with TCR activation enhanced Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation (Figure 7). The induction of effector cytokines, increased survival, and proliferation have been linked to Erk1/Erk2 and Akt function in T cells [3,69], although a recent report suggests that Akt activation may be dispensable for mouse CD8 T cell proliferation and survival [70]. Accordingly, Biswas and co-workers concluded that the pro-survival protein Bcl-XL was induced in an Erk1/Erk2-dependent manner upon TLR2 co-stimulation in mouse CD4 T cells [23]. Furthermore, the activation of these pathways likely augments the function of transcription factors linked to cytokine and chemokine production in T cells, including the AP-1 family and the β-catenin/TCF-1 complex [2,69,71]. Several studies have also demonstrated that the induction of these kinases promotes IL-10 release downstream of TLRs [59,72,73]. Since we observed that TLR2 activation alone induced Akt and Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation as well as IL-10 production, these data suggest that these kinases also control IL-10 release downstream of TLR2 in human T cells. Thus, Akt and Erk1/Erk2 likely play a critical role in regulating TLR2 function in human T cells.

Collectively, our findings suggest that the TLR2 has an important regulatory function in activated human T cells. In the absence of cognate antigen, this receptor appears to program activated T cells to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines in an effort to dampen the adaptive immune response and prevent immunopathology. Following TCR activation, however, TLR2 stimulates effector or memory T cells to more efficiently fight infectious agents while intrinsically limiting the amount and extent of inflammatory mediators these cells can produce. Interestingly, TLR2 specifically signals via the Erk1/Erk2 and Akt, but not NF-κB pathways, in human T cells, demonstrating that TLR2 activates distinct signaling mechanisms compared to mouse T cells. In the end, these studies emphasize the need to better elucidate the signaling pathways driving TLR2 function in human immune cells.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that TLR2 induction enhances Akt and Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation and that this receptor synergizes with TCR-mediated signals that activate these proteins. In contrast to other reports using murine T cells, we also found that TLR2 signaling in human T cells does not activate NFκB. These studies demonstrate that TLR2 induces distinct intracellular signaling pathways to influence mouse and human T cell activation.

Highlights.

TLR2 enhances TCR activation that regulates downstream effector functions.

It is unknown where TCR and TLR2-induced signals converge to augment human T cell activation.

We have demonstrated that TLR2 specifically augments Akt and Erk1/Erk2 function, but not NFκB activity, in human T cells

This study reveals that TLR2 utilizes distinct signaling pathways in human T cells versus mouse T cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Rebekah Bartelt and Mikaela Tremblay for their thoughtful discussions and careful critique of this manuscript, and Dr. Gail Bishop for the gift of reagents. This work was supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship to NMC (11PRE7390070) and the Biological Sciences Funding Program from the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of Iowa, a Scientist Development Grant 0830244N from the American Heart Association, and R01 CA136729 from the National Institutes of Health to JCDH. NMC, MYB, and CK were supported by the NIH Predoctoral Training Grant in Immunology (T32 AI007485) and NCO was supported by the Dental Research NIH Training Grant (T32 DE014678).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:591–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nel AE. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2002;109:758–770. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kane LP, Weiss A. Immunol Rev. 2003;192:7–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruz-Orcutt N, Houtman JC. Molecular immunology. 2009;46:2274–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd CM, Hessel EM. Nature reviews Immunology. 2010;10:838–848. doi: 10.1038/nri2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jutel M, Akdis CA. Current allergy and asthma reports. 2011;11:139–145. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jager A, Kuchroo VK. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2010;72:173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atalar K, Afzali B, Lord G, Lombardi G. Current opinion in organ transplantation. 2009;14:23–29. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32831b70c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahoute C, Herbin O, Mallat Z, Tedgui A. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2011;8:348–358. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Croft M. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:609–620. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan Y, Ranoa DR, Jiang S, Mutha SK, Li X, Baudry J, Tapping RI. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:5094–5103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brikos C, O’Neill LA. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2008:21–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-72167-3_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanin-Zhorov A, Nussbaum G, Franitza S, Cohen IR, Lider O. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2003;17:1567–1569. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1139fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsan MF, Gao B. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2004;76:514–519. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0304127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills KH. Nature reviews Immunology. 2011;11:807–822. doi: 10.1038/nri3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Karin M. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1217:191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corr SC, O’Neill LA. Journal of innate immunity. 2009;1:350–357. doi: 10.1159/000200774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercier BC, Cottalorda A, Coupet CA, Marvel J, Bonnefoy-Berard N. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:1860–1867. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cottalorda A, Verschelde C, Marcais A, Tomkowiak M, Musette P, Uematsu S, Akira S, Marvel J, Bonnefoy-Berard N. European journal of immunology. 2006;36:1684–1693. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geng D, Zheng L, Srivastava R, Velasco-Gonzalez C, Riker A, Markovic SN, Davila E. Cancer research. 2010;70:7442–7454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asprodites N, Zheng L, Geng D, Velasco-Gonzalez C, Sanchez-Perez L, Davila E. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2008;22:3628–3637. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komai-Koma M, Jones L, Ogg GS, Xu D, Liew FY. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:3029–3034. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400171101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswas A, Banerjee P, Biswas T. Molecular immunology. 2009;46:3076–3085. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardt-Pargmann D, Wechsler M, Krieg AM, Vollmer J, Jurk M. Immunobiology. 2011;216:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarron M, Reen DJ. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:55–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyirenda MH, Sanvito L, Darlington PJ, O’Brien K, Zhang GX, Constantinescu CS, Bar-Or A, Gran B. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:2278–2290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SM, Joo YD, Seo SK. Immune Netw. 2009;9:127–132. doi: 10.4110/in.2009.9.4.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caron G, Duluc D, Fremaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H, Delneste Y. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:1551–1557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lancioni CL, Li Q, Thomas JJ, Ding X, Thiel B, Drage MG, Pecora ND, Ziady AG, Shank S, Harding CV, et al. Infection and immunity. 2011;79:663–673. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00806-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Maren WW, Jacobs JF, de Vries IJ, Nierkens S, Adema GJ. Immunology. 2008;124:445–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberg HH, Juricke M, Kabelitz D, Wesch D. European journal of cell biology. 2011;90:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cristofaro P, Opal SM. Drugs. 2006;66:15–29. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imanishi T, Hara H, Suzuki S, Suzuki N, Akira S, Saito T. Journal of immunology. 2007;178:6715–6719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietz AB, Bulur PA, Emery RL, Winters JL, Epps DE, Zubair AC, Vuk-Pavlovic S. Transfusion. 2006;46:2083–2089. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lahm HW, Stein S. Journal of chromatography. 1985;326:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)87461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartelt RR, Cruz-Orcutt N, Collins M, Houtman JC. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarember KA, Godowski PJ. J Immunol. 2002;168:554–561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu H, Komai-Koma M, Xu D, Liew FY. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:7048–7053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601554103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houtman JC, Houghtling RA, Barda-Saad M, Toda Y, Samelson LE. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:2449–2458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jefferies CA, Doyle S, Brunner C, Dunne A, Brint E, Wietek C, Walch E, Wirth T, O’Neill LA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:26258–26264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horwood NJ, Page TH, McDaid JP, Palmer CD, Campbell J, Mahon T, Brennan FM, Webster D, Foxwell BM. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:3635–3641. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semaan N, Alsaleh G, Gottenberg JE, Wachsmann D, Sibilia J. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:3485–3491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schaeffer EM, Debnath J, Yap G, McVicar D, Liao XC, Littman DR, Sher A, Varmus HE, Lenardo MJ, Schwartzberg PL. Science. 1999;284:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5414.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu KQ, Bunnell SC, Gurniak CB, Berg LJ. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;187:1721–1727. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas JA, Miller AT, Atherly LO, Berg LJ. Immunological reviews. 2003;191:119–138. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuang T, Ulevitch RJ. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2001;1518:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasan U, Chaffois C, Gaillard C, Saulnier V, Merck E, Tancredi S, Guiet C, Briere F, Vlach J, Lebecque S, et al. Journal of immunology. 2005;174:2942–2950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Govindaraj RG, Manavalan B, Lee G, Choi S. PloS one. 2010;5:e12713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wild CA, Brandau S, Lindemann M, Lotfi R, Hoffmann TK, Lang S, Bergmann C. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2010;136:1253–1259. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2010.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bell MP, Svingen PA, Rahman MK, Xiong Y, Faubion WA., Jr Journal of immunology. 2007;179:1893–1900. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quigley M, Martinez J, Huang X, Yang Y. Blood. 2009;113:2256–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gamper CJ, Powell JD. Front Immunol. 2012;3:312. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Texereau J, Chiche JD, Taylor W, Choukroun G, Comba B, Mira JP. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 7):S408–415. doi: 10.1086/431990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tapping RI, Omueti KO, Johnson CM. Biochemical Society transactions. 2007;35:1445–1448. doi: 10.1042/BST0351445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee EY, Yim JJ, Lee HS, Lee YJ, Lee EB, Song YW. International journal of immunogenetics. 2006;33:211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2006.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bjornvold M, Munthe-Kaas MC, Egeland T, Joner G, Dahl-Jorgensen K, Njolstad PR, Akselsen HE, Gervin K, Carlsen KC, Carlsen KH, et al. Genes and immunity. 2009;10:181–187. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaisho T, Akira S. Current molecular medicine. 2003;3:759–771. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin M, Schifferle RE, Cuesta N, Vogel SN, Katz J, Michalek SM. Journal of immunology. 2003;171:717–725. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barr TA, Brown S, Ryan G, Zhao J, Gray D. European journal of immunology. 2007;37:3040–3053. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jankovic D, Kugler DG, Sher A. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:239–246. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Testro AG, Visvanathan K. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:943–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frolova L, Drastich P, Rossmann P, Klimesova K, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56:267–274. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7303.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang L, Qiao G, Ying H, Zhang J, Yin F. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;400:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown J, Wang H, Suttles J, Graves DT, Martin M. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:44295–44305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loegering DJ, Lennartz MR. Enzyme Res. 2011;2011:537821. doi: 10.4061/2011/537821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Park J, Feng J, Li Y, Hammarsten O, Brazil DP, Hemmings BA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:6169–6174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huston E, Lynch MJ, Mohamed A, Collins DM, Hill EV, MacLeod R, Krause E, Baillie GS, Houslay MD. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:12791–12796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805167105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fruman DA. Current opinion in immunology. 2004;16:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Macintyre AN, Finlay D, Preston G, Sinclair LV, Waugh CM, Tamas P, Feijoo C, Okkenhaug K, Cantrell DA. Immunity. 2011;34:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu Q, Sharma A, Sen JM. Immunol Res. 2010;47:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s12026-009-8137-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hirata N, Yanagawa Y, Iwabuchi K, Onoe K. Cell Immunol. 2009;258:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chandra D, Naik S. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154:224–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]