Abstract

Objective

4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) is one of the major aldehydes formed during lipid peroxidation, and is believed to play a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The objective of the present study is to investigate the effect of HNE on tissue factor (TF) procoagulant activity expressed on cell surfaces.

Approach and Results

TF activity and antigen levels on intact cells were measured in factor Xa generation and TF mAb binding assays, respectively. Exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) on the cell surface was analyzed in thrombin generation assay or by binding of a fluorescent dye-conjugated annexin V. 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate was used to detect the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Our data showed that HNE increased the procoagulant activity of unperturbed THP-1 cells that express traces of TF antigen, but had no effect on unperturbed endothelial cells that express no measurable TF antigen. HNE increased TF procoagulant activity but not TF antigen of both activated monocytic and endothelial cells. HNE treatment generated ROS, activated p38 MAPK, and increased the exposure of PS at the outer leaflet in THP-1 cells. Treatment of THP-1 cells with an antioxidant, N-acetyl cysteine, suppressed the above HNE-induced responses, and negated the HNE-mediated increase in TF activity. Blockade of p38 MAPK activation inhibited HNE-induced PS exposure and increased TF activity.

Conclusions

HNE increases TF coagulant activity in monocytic cells through a novel mechanism involving p38 MAPK activation that leads to enhanced PS exposure at the cell surface.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, HNE, microparticles, oxidative stress, p38 MAPK, tissue factor

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cellular oxidative stress mediated by lipid peroxidation (LPO), and its products are known major contributors to the initiation and propagation of atherosclerosis.1 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) is one of the most abundant reactive aldehydes generated from oxidation of ω6 fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid (AA) and linoleic acid (LA).2 The concentration of the free form of HNE in the human plasma ranges from 0.1 μM up to 1.4 μM, and can increase 10 times or more during oxidative stress in vivo.3 It has been shown that HNE can accumulate in the membrane at concentrations ranging from 10 μM to 5 mM in response to oxidative stress and inflammation.4, 5 HNE is a highly reactive and stable molecule.6 The amphipathic nature of HNE results in its association with the membranes where it is generated, but is also capable of moving within and between cellular compartments and thus can exert its effect on various cellular targets (proteins, lipids, and DNA) far away from its site of origin.7 HNE can interact covalently with proteins, mainly with the amino (-NH2) groups of lysine and histidine and thiol groups of cysteine, forming Michael adducts, which result in either gain or loss of protein function.8–10 Recent studies have demonstrated that HNE contributes to the progression of atherosclerosis through its cytotoxic effects and modulation of various signaling pathways.11–14 Several studies utilizing human and animal models have linked HNE with different stages of atherosclerosis.7 High levels of HNE were found in the atherosclerotic lesions of human subjects and in animal models.15, 16 HNE can covalently bind to low density lipoproteins (LDL) and facilitate their uptake by macrophages.17, 18 HNE was shown to activate early steps of inflammation and monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells in atherosclerosis.19

Tissue factor (TF), a plasma membrane glycoprotein, plays a crucial role in maintaining hemostasis by acting as a cofactor for plasma clotting factor VII (FVII) and activated factor FVII (FVIIa).20 TF is expressed constitutively on cell surfaces of many extravascular cells including fibroblasts and pericytes in and surrounding blood vessel walls but is absent in cells that come in direct contact with blood such as monocytes and endothelial cells under normal physiological conditions.21, 22 TF expression can be induced in these cells in response to various pathological stimuli,23, 24 and the resultant aberrant expression of TF could lead to intravascular thrombus formation, the precipitating event in acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and ischemic stroke.25, 26 Although a number of studies have examined the effects of modified LDLs and LPO products on TF expression,27–35 we are not aware of any study that specifically examined the effect of HNE on TF activity.

TF expressed on cells within the atherosclerotic plaque such as vascular smooth muscle cells, foam cells, monocytes, and endothelial cells overlying atherosclerotic plaques36–38 is responsible for the thrombogenicity associated with plaque rupture.39, 40 Since HNE is a major aldehyde of LPO,9, 41 and presence of both HNE and TF has been associated with various stages of atherosclerosis, in the present study, we investigated the effect of HNE on TF expression and its procoagulant function. The data presented in this manuscript show that HNE increases procoagulant activity of the pre-existing TF on cell surfaces through decryption as well as via generation of TF-positive microparticles (MP). Our studies show that HNE-mediated activation of p38 MAPK induces exposure of phosphatidylserine (PS) in monocytic cells without altering LPS-induced TF protein levels.

Materials and Methods

Material and Methods are available in the online-only Data Supplement.

Results

Effect of HNE on TF activity on cell surfaces of monocytic and endothelial cells

Unstimulated THP-1 cells and HCAEC were treated with HNE, 20 and 40 μM, respectively, for varying time periods (5 min to 24 h), and TF activity on intact cells was analyzed in FX activation assay. Unperturbed THP-1 cells exhibited low levels of TF activity, and prolonged exposure to HNE (4 h or more) increased the TF activity by 4-fold or higher (data not shown). Treatment of unperturbed THP-1 cells with varying concentrations of HNE revealed that 10 μM HNE was sufficient to significantly increase TF activity. TF activity reached peak with 20 to 40 μM HNE treatment, and thereafter declined (Fig. 1A). Analysis of TF antigen by immunoblot analysis revealed a faint band (barely visible), corresponding to TF mol. wt. (~50 kDa), in unstimulated THP-1 cells, which did not change in HNE-treated cells (data not shown), indicating that HNE treatment did not induce TF protein expression. Unperturbed HCAEC expressed no measurable TF activity, and HNE treatment (40 μM for 4 h) did not induce TF activity. Similarly, no TF antigen was found in unperturbed HCAEC, either untreated or treated with HNE (data not shown).

Figure 1.

HNE-mediated increase in TF procoagulant activity in THP-1 cells and HCAEC, and its comparison with other reactive aldehydes. THP-1 cells or HCAEC were treated with HNE and other compounds as described below, and at the end of treatment, cell surface TF activity was determined in FX activation assay. (A) Unperturbed THP-1 cells were treated with varying concentrations of HNE for 4 h. (B) THP-1 cells were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 4 h in RPMI medium containing 2% serum, and then treated with varying concentrations of HNE for 4 h. (C) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with 20 μM HNE for varying time periods. (D and E) HCAEC monolayers cultured in 48-well plate were perturbed with 20 ng/ml of each TNF-α and IL1-β for 4 h in 2% serum containing EBM-2 medium, and then treated with varying concentrations of HNE for 4 h (D) or with 40 μM HNE for varying time periods (E). (F and G) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells (F) or cytokine-activated HCAEC (G) were treated with HNE and other reactive aldehydes for 4 h (20 μM concentration for THP-1 cells and 40 μM concentration for HCAEC). UN, unperturbed cells. In panel A, * denotes that the value is statistically significantly higher compared to cells not treated with HNE (p <0.05). In other panels, # denotes statistically significantly different from unperturbed cells (p <0.01); * denotes statistically significant difference compared to LPS- or TNF-α/IL1-β-stiumlated cells that were not subjected to HNE or other treatments (p <0.01).

Since the above data suggest that HNE does not induce TF protein but enhances the activity of TF that is already present at the cell surface, we next examined the effect of HNE on monocytic and endothelial cells that are perturbed to induce TF protein. Before using perturbed THP-1 cells as a model system to investigate the effect of HNE, we first examined whether HNE influences TF activity of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs). LPS-perturbed MDMs were exposed to HNE (40 or 80 μM) for varying times (15 min to 6 h), and TF coagulant activity on intact cells was determined in FX activation assay. Both concentrations of HNE enhanced TF activity by 4 to 5-fold at 3 or 6 h of HNE treatment (data not shown). Next, LPS-perturbed MDMs were treated with varying concentrations of HNE for 4 h. HNE treatment significantly increased TF activity in LPS-perturbed macrophages in a dose-dependent manner, reaching optimum at 40 μM of HNE (3.5-fold increase over LPS alone treated macrophages; Supplement Fig. I). Next, we examined whether this effect of HNE could be mimicked in THP-1 cells. As observed with MDMs, HNE treatment markedly increased cell surface TF activity of LPS-perturbed THP-1 cells in a dose-dependent (Fig. 1B) and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). A concentration of 20 to 40 μM HNE exerted the maximal effect, a 4 to 5-fold increase in TF activity over LPS alone treated cells.

HNE treatment also increased TF activity in cytokine-perturbed HCAEC (Fig. 1D and 1E) and HUVEC (data not shown). A 2-fold increase in TF activity was observed at 20 μM HNE, and increasing the HNE concentration to 40 to 80 μM further enhanced TF activity (3-fold) in HCAEC (Fig. 1D). Treatment of HNE-treated THP-1 cells or HCAEC with inhibitory TF mAb (5G9) completely inhibited factor X activation indicating that HNE-mediated increase in cell surface coagulant activity was TF specific (data not shown). Additional studies revealed that the concentrations of HNE and treatment durations used in above experiments had no significant effect on cell viability as measured in trypan blue dye exclusion method or MTT assay (Supplement Fig. II).

Effect of other LPO products on TF activity

We next performed a comparative evaluation of various fatty acids and aldehydes generated in the process of LPO for their potential to induce TF activity in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells and TNF-α + IL1-β-perturbed HCAEC. THP-1 cells and HCAEC were treated with 20 and 40 μM, respectively, of HNE, 4-hydroxy hexenal, 2,4-decadional (DDE), acrolein, malondialdehyde, AA, LA, and methylglyoxal, and cell surface TF activity was measured. As shown in Fig. 1F, apart from HNE, only DDE treatment significantly increased TF activity in THP-1 cells. In case of HCAEC, 4-hydroxy hexenal, acrolein and DDE induced TF activity to a similar or slightly lower extent to that of HNE (Fig. 1G). Here, it may be pertinent to note that HNE being the most abundant and reactive molecule formed during LPO as compared to others,9, 41 it may be a more physiologically relevant molecule to affect TF procoagulant activity. Therefore, we used only HNE in further studies.

HNE increases TF procoagulant activity without increasing TF protein levels

To determine whether HNE-mediated increase in TF activity in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells is due to further increase in TF antigen, we quantitatively measured both surface and total TF antigen levels in THP-1 cells treated with a control vehicle or HNE. As shown in Fig. 2A, cell surface binding analysis performed using radiolabeled TF mAb (TF 9C3) showed no differences in cell surface TF antigen levels between control vehicle- and HNE-treated THP-1 cells. Similarly, no differences were found in total TF antigen levels between control and HNE-treated THP-1 cells as determined by ELISA (Fig. 2B). These data show, as observed with unperturbed cells, that HNE treatment does not increase TF antigen levels in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells. This indicates that HNE-mediated increase in TF activity did not stem from increased TF protein levels at the cell surface.

Figure 2.

HNE increases TF activity in monocytic cells without increasing TF protein levels but increasing phosphatidylserine at the cell surface. (A) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with HNE (20 μM) for 4 h in RPMI medium containing 2% serum. At the end of the treatment period, cells were washed, chilled on ice for 10 min, and then 125I-TF mAb 9C3 (10 nM) was added to the cells. After 2 h incubation at 4°C, 125I-TF mAb bound to the cells was determined. ns, not statistically significant difference. (B) THP-1 cells were treated same as in panel A except that cells were lysed at the end of HNE treatment in TBS containing 2% Triton X-100 and 5 mM EDTA and total cell TF antigen levels were determined in TF-specific ELISA. (C) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with HNE as described in (A). At the end of HNE treatment, cells were incubated with ± 200 nM annexin V for 30 min at 37°C and then cell surface TF activity was measured. * denotes statistically significant inhibition in the presence of annexin V (p < 0.01). (D) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with HNE as described in (A), and prothrombinase activity was measured by incubating cells with buffer B containing FVa (10 nM) and FXa (1 nM), and subsequent addition of prothrombin (5 μM). (E) NBD-PS uptake. Unperturbed and LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with a control vehicle or HNE (20 μM for 1 h) and then loaded with NBD-PS at 4°C. After removing the free NBD-PS, cells were incubated for 10 min at 37°C and then fluorescence intensity was measured in the presence or absence of cell impermeant quencher dithionite. The percent NBD-PS internalized was calculated as described in methods. * denotes statistically significant difference compared to cells not treated with HNE (p <0.05). UN, unperturbed cells.

HNE does not modify TF protein, but increases exposure of phosphatidylserine on cell surfaces

HNE is known to form adducts with several proteins by binding to lysine, histidine, and cysteine amino acid residues and thus modulating their function and activity.8–10 Therefore, we evaluated the effect of HNE on TF activity in a buffer system containing relipidated purified TF. Since HNE is known to bind to PE,42 we analyzed the effect of HNE on TF relipidated in either PC/PS or PC/PS/PE vesicles. HNE treatment (20 μM for 4h) had no effect on the activity of TF relipidated in either PC/PS or PC/PS/PE vesicles (data not shown). Further, western blot analysis with HNE antibodies failed to detect TF-HNE complex. Similarly, HNE antibodies failed to detect TF-HNE complex in TF immunoprecipitate of cell lysates of LPS-perturbed THP-1 cells treated with HNE (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates of LPS-perturbed THP-1 cells treated with HNE showed several HNE-protein adducts, mostly at higher mol. wt. (>60 KDa), which ran as a smear on the gel. Overall, these data indicate that it is unlikely that potential modification of amino acids on TF by HNE is responsible for the increased TF activity observed in cell systems.

It has been reported that on cell surfaces only small amounts of TF is coagulant active (capable of activating factor X) whereas majority of the TF is inactive (cryptic). Several mechanisms have been proposed regarding transformation of cryptic TF into procoagulant active TF, but the exposure of PS on the cell surface in response to various stimuli has been widely accepted.43 To test whether HNE-mediated increase in TF activity at the cell surface is due to increased PS at the cell surface in HNE treated cells, we investigated the effect of annexin V, a protein known to bind PS, on HNE-mediated increased TF activity. As shown in Fig. 2C, blocking anionic phospholipids on the cell surface with annexin V abrogated HNE-mediated increased TF activity. Consistent with the possibility that HNE treatment enhances PS exposure to the outer leaflet, treatment of THP-1 cells, either unperturbed or LPS-perturbed, with HNE significantly enhanced the prothrombinase activity at the cell surface (Fig. 2D). As observed with TF activity, annexin V completely inhibited HNE-mediated increase in prothrombinase activity (data not shown). In additional studies, we analyzed the effect of HNE on transmembrane transport of PS in THP-1 cells using NBD-PS. As shown in Fig. 2E, approximately 70 to 90% of NBD-PS associated with the cell surface was internalized in unperturbed or LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells over 10 min, and HNE treatment significantly decreased the uptake of NBD-PS. These data indicate that HNE inhibits the PS influx. Overall, these data suggest that HNE treatment increases the exposure of anionic phospholipids at the outer leaflet, and that increased anionic phospholipids at the cell surface is primarily responsible for the increased TF activity upon HNE treatment.

HNE-induced ROS generation and its potential role in increasing the activity of TF

HNE was shown to stimulate ROS generation in different cell types.9 Therefore, we investigated whether HNE leads to generation of ROS in THP-1 cells and HCAEC, and whether generation of ROS is responsible for HNE-mediated increase in TF activity. To determine this, both unperturbed and perturbed THP-1 cells and HCAEC were treated with HNE for 1 h and ROS production was measured by H2DCFDA oxidation. As shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, HNE treatment significantly enhanced ROS production in both unperturbed and perturbed THP-1 cells and HCAEC. Next, to examine the possible source of HNE-mediated ROS generation, perturbed THP-1 cells and HCAEC were treated with inhibitors of mitochondrial electron transport chain (rotenone), xanthine oxidase (allopurinol) and NAPDH-oxidase (apocynin) prior to HNE treatment. Rotenone inhibited HNE-induced ROS generation significantly, but not completely, in THP-1 cells (Fig. 3A) but had no effect in HCAEC. Other inhibitors had no noticeable effect on the HNE-induced ROS generation, either in THP-1 cells or HCAEC (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3C, of all the inhibitors tested, only rotenone showed significant (~50% inhibition) of HNE-mediated increase in TF activity in THP-1 cells. These results suggest that HNE-induced mitochondrial ROS production contributes partially but significantly to HNE-mediated activation of TF activity in THP-1 cells. In contrast to THP-1 cells, none of the inhibitors were effective in attenuating HNE-mediated increase in TF activity in HCAEC (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

HNE-induced ROS generation and its effect on HNE-mediated increase in TF activity. Unperturbed or LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells (A), unperturbed or TNF-α/IL1-β-stimulated HCAEC (B) were loaded with H2DCFDA (for THP-1 cells, 5 μM for 10 min; HCAEC, 10 μM for 30 min) in serum-free medium. After removing the supernatant, cells were washed once with serum-free medium and treated with HNE (20 μM for THP-1 cells; 40 μM for HCAEC) for 45 min. At the end of HNE treatment, cells were washed twice with HBS and fluorescence images were obtained by confocal microscopy, and the fluorescence intensity associated with the cells was quantified. Where cells were treated with rotenone (2 μM), it was added to the cells after 3 h of LPS or cytokine stimulation. (C) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells or (D) TNF-α/IL1-β-stimulated HCAEC were incubated with various ROS inhibitors - rotenone (Rot, 2 μM), allopurinol (Al, 100 μM), or apocynin (AP, 30 μM) for 1 h followed by a 4 h treatment with 20 or 40 μM HNE, respectively. At the end of treatment, TF activity was determined in FX activation assay. UN, unperturbed cells; # denotes statistically significant difference compared to unperturbed cells (p <0.01); * denotes statistically significant difference compared to HNE-treated cells in the absence of inhibitors (p < 0.01).

Involvement of p38 MAPK activation in HNE-mediated increase of TF activity through regulation of PS exposure

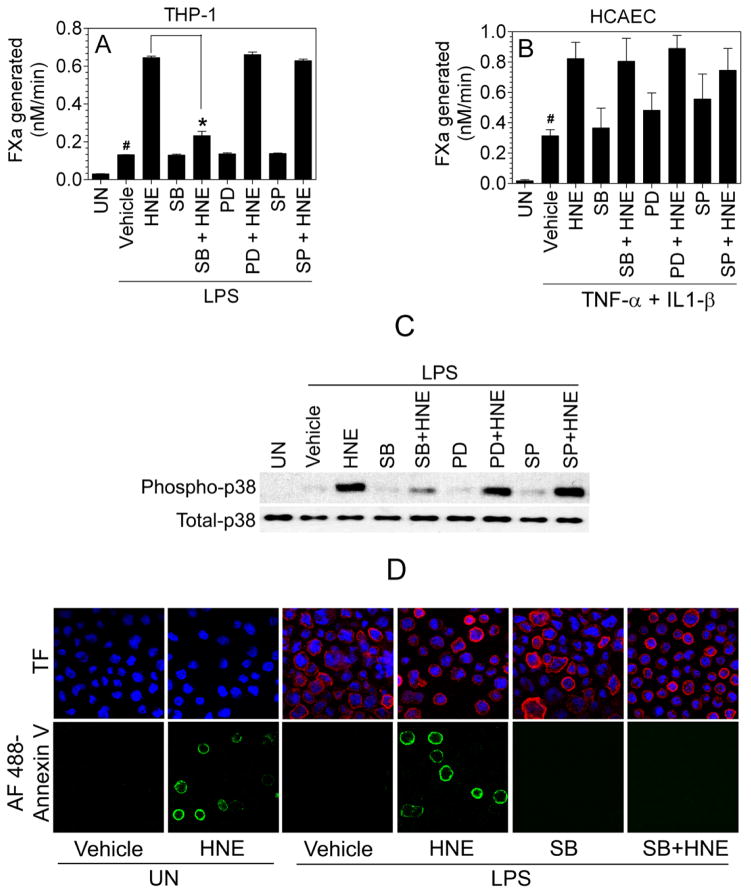

HNE is known to activate MAPK signaling pathways.9 Recent studies indicate that p38 MAPK activation may play a role in PS exposure in erythrocytes and platelets.44, 45 Therefore, to elucidate the putative signal transduction mechanism responsible for activation of TF by HNE, we examined the effect of specific MAPK inhibitors on HNE-mediated increase in TF activity (Fig. 4A and 4B). As shown in Fig. 4A, pre-incubation of cells with p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580), prior to addition of HNE, completely attenuated HNE-mediated activation of TF whereas inhibitors of JNK (SP600125) and ERK (PD98059) were without any effect. We further confirmed the involvement of p38 MAPK signaling in HNE-mediated effect by immunoblot analysis of p38 MAPK activation. As shown in Fig. 4C, HNE treatment increased phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, which was attenuated by the p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580) whereas JNK and ERK inhibitors had no effect on p38 MAPK activation. Here, it may be pertinent to note that although LPS treatment, in itself, activates p38 MAPK to some extent, phospho p38 MAPK levels declined to basal levels by the time cells were subjected to HNE treatment (Supplement Fig. III). HNE activation of p38 MAPK does not dependent on LPS as HNE was found to activate p38 MAPK in unperturbed THP-1 cells (Supplement Fig. III). HNE-induced phospho p38 MAPK levels were sustained for 4 h or more in THP-1 cells (Supplement Fig. III).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of p38 MAPK pathway blocks HNE-mediated increased TF activity in THP-1 cells. LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells (A) or TNF-α/IL1-β-stimulated HCAEC (B) were incubated with various MAPK inhibitors (20 μM) - SB203580 (SB), SP600125 (SP), and PD98059 (PD) - for 1 h followed by a 4 h treatment with 20 or 40 μM HNE, respectively. At the end of the treatment, TF activity was determined in FX activation assay. (C) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with inhibitors, same as in panel A, and at the end of the treatment, cells were lysed and subjected to a non-reducing SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho p38 MAPK and total p38 MAPK antibodies. (D) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells treated with inhibitors and HNE as described in panel A were stained for cell surface PS using AF488-annexin V and immunostained with TF mAb. DAPI was used for nucleus staining. The fluorescence images were obtained by confocal microscopy. UN, unperturbed cells; # denotes statistical significant difference compared to unperturbed cells (p <0.01); * denotes statistically significant difference compared to HNE-treated cells in the absence of inhibitors (p < 0.01).

To demonstrate that HNE-induced p38 MAPK activation is responsible for exposure of PS in THP-1 cells, we performed fluorescence staining of THP-1 cells treated with HNE ± SB203580 with AF488-annexin V to evaluate PS exposure at the cell surface. As shown in Fig. 4D, HNE treatment increased the number of cells brightly stained with AF488-annexin V and pretreatment of cells with p38 MAPK inhibitor markedly reduced AF488-annexin V staining. This data provides strong evidence that HNE-led activation of p38 MAPK signaling is responsible for PS exposure at the cell surface. Interestingly, in contrast to THP-1 cells, p38 MAPK inhibitor had only a negligible effect on HNE-dependent TF activation in HCAEC (Fig. 4B), indicating that an alternate signaling pathway may exist for HNE-mediated TF activation in endothelial cells.

Thiol protective agents attenuate HNE-mediated ROS generation, p38 MAPK activation and increase in TF activity

The GSH/GST system is the most dominant system involved in the rapid detoxification and disposal of HNE from cells.46 N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and N-2 mercaptopropionyl glycine (MPG) are known antioxidants and thiol-protectants that exert protective effects by replenishing cellular GSH. This prompted us to examine whether NAC can attenuate HNE-mediated cellular ROS generation, p38 MAPK activation, and increase in TF activity. As shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, pretreatment of perturbed THP-1 cells or HCAEC with NAC completely abrogated HNE-induced ROS generation. NAC and MPG also inhibited the HNE-induced p38 MAPK activation in THP-1 cells (Fig. 5C) and increase in TF activity at the cell surface in both perturbed THP-1 cells (Fig. 5D) and HCAEC (Fig. 5E). In additional studies, we examined the effect of NAC on HNE-induced PS exposure at the cell surface in THP-1 cells. Analysis of PS exposure at the cell surface by AF488-annexin V binding to intact THP-1 cells showed that NAC completely attenuated HNE-induced PS exposure at the cell surface without affecting TF antigen levels (Fig. 5F). Taken together, these results suggest that thiol protective agents can attenuate HNE-induced increased TF activity by inhibiting HNE-induced upstream signaling events, such as ROS generation, p38 MAPK activation, and PS exposure to the outer leaflet.

Figure 5.

Thiol protecting agents attenuate HNE-induced ROS generation and increased TF activity. THP-1 cells (A) or HCAEC (B), stimulated with LPS or cytokines, respectively, were treated with NAC (3 mM) for 1 h and then loaded with H2DCFDA (experimental conditions were essentially same as in Fig. 3). Thereafter, the cells were treated with 20 or 40 μM HNE, respectively, for 45 min, and then analyzed for ROS generation. (C) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with NAC (3 mM) or MPG (100 μM) for 1 h, followed by addition of HNE (20 μM). At the end of 4 h HNE treatment, the cells were lysed and subjected to a non-reducing SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho p38 MAPK or total p38 MAPK antibodies. (D and E). LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells or cytokine-stimulated HCAEC were treated with NAC (3 mM) or MPG (100 μM) for 1 h followed by HNE (20 μM for THP-1 cells and 40 μM for HCAEC) for 4 h. At the end of HNE treatment, TF activity was determined in FX activation assay. (F) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells treated with NAC followed by HNE (as described in panel D) were stained for cell surface PS using AF488-annexin V, and immunostained with TF mAb. DAPI was used for nucleus staining. (G) LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were treated with a control vehicle or rotenone (2 μM for 1 h) followed by HNE for 4 h. The cells were stained with AF488-annexin V and immunostained with TF mAb (9C3). UN, unperturbed cells; # denotes statistically significant difference compared to unperturbed cells (p <0.01); * denotes statistically significant difference compared to cells treated with HNE in the absence of thiol protectants (p < 0.01).

Rotenone, an inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transport chain, which partly but significantly inhibited HNE-induced ROS generation and TF activity (see Fig. 3), had no effect on HNE-induced p38 MAPK activation (data not shown). However, rotenone partly suppressed HNE-induced PS exposure at the cell surface (Fig. 5G; % annexin V positive cells in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells treated with HNE, 15.1± 1.2; in cells pretreated with rotenone before adding HNE, 8.9 ±1.2, p = 0.0026). These data indicate that HNE-induced p38 MAPK activation may be independent of HNE-induced ROS generation via mitochondrial respiratory complex I, but the later process could also contribute to externalization of PS to some extent.

HNE releases TF-bearing microparticles from endothelial cells and fibroblasts

TF decryption results in increased TF activity at the cell surface as well as generation of highly procoagulant TF-positive microparticles.47 Therefore, we investigated whether apart from activating cell surface TF, HNE can induce production of TF-bearing microparticles. HNE treatment of perturbed HCAEC (Fig. 6A) and WI-38 fibroblasts (Fig. 6B) significantly increased TF activity associated with microparticles in a time-dependent manner. Surprisingly, although activation of monocytes/macrophages by various agents was shown to generate procoagulant microparticles,48 HNE treatment of LPS-perturbed THP-1 cells did not lead to further enhancement of microparticle-associated TF activity compared to LPS alone treated cells (data not shown).

Figure 6.

HNE treatment releases TF bearing microparticles. TNF-α + IL1-β-stimulated HCAEC (A) or WI-38 fibroblasts (B) were treated with 40 μM HNE for varying time periods. At the end of the treatment, overlying medium was collected, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 1 h to isolate MP. TF activity associated with MP was measured in FX activation assay. UN, unperturbed cells; * denotes statistically significant difference compared to cells not treated with HNE (p < 0.01).

Discussion

Although various lipid peroxidation products were shown to induce tissue factor (TF) protein expression and activity in monocytes and endothelial cells,28, 49, 50 the effect of HNE, one of the most abundant aldehydes formed during LPO of ω6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, on TF protein expression and coagulant function has not been investigated. Here, we show for the first time that (1) HNE increases the procoagulant activity of TF in perturbed monocytic and endothelial cells without increasing TF antigen levels; (2) HNE-induced mitochondrial ROS generation is partially responsible for increased TF activity in monocytic cells; (3) HNE-led activation of p38 MAPK pathway followed by PS exposure is responsible primarily for increased TF activity in monocytic cells; (4) treatment of monocytic and endothelial cells with thiol protectants attenuates HNE-mediated PS exposure and increased TF activity at the cell surface; (5) HNE increases the generation of TF bearing microparticles from perturbed endothelial cells and fibroblasts.

Although TF is essential for maintaining hemostasis, the aberrant expression of TF induced by various disease conditions results in intravascular thrombotic complications.51, 52 Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation contribute to various cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis.53–56 A number of studies have examined the effects of modified LDL on TF expression, which failed to provide conclusive data as they showed increase, no change or even inhibition of TF expression.27, 29–35 Aldehydes are the end products of polyunsaturated fatty acid oxidation and have been shown to play a key role in the progression of atherosclerotic process by modifying many important biological functions.57 The best known effect of HNE and other reactive aldehydes is their reaction with Lys residues of apolipoprotein B, which leads to the recognition of oxidized LDL by the scavenger receptors.17 This appears to be a predominant mechanism by which LPO end products contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis.1, 58 However, HNE can also modulate various cellular functions that contribute to atherosclerotic process by directly interacting with biomolecules (proteins, lipids and DNA), activation of stress signaling pathways, and inducing intracellular oxidative stress.57–59 Earlier studies showed that LPO and its end products can modulate TF expression and procoagulant activity in various cell systems, mostly inducing TF mRNA and protein synthesis.28, 49, 50, 60 Cabre et al.28 showed that hexenal and DDE, two other aldehydes produced in LPO, increased TF expression by transcriptional activation of TF gene in vascular smooth muscle cells. In the present study, we find that HNE increases TF procoagulant activity in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells and cytokine-stimulated HCAEC without increasing TF antigen. Out of all biologically relevant aldehydes we tested, HNE appears to be the most potent in increasing TF activity in both THP-1 cells and HCAEC. However, in addition to HNE, DDE was also found to effectively increase TF activity of both perturbed monocytic and endothelial cells. It may be pertinent to note here that although DDE may be most biologically active but it is least abundant in plasma.28, 61 In earlier studies, AA and LA, the precursors of HNE, were shown to either enhance TF protein and activity49 or to inhibit LPS-induced TF expression in macrophages.60 In the present study, we found that both AA and LA had no significant effect on TF activity in THP-1 cells as well as HCAEC. However, it may be pertinent to note here that our experimental design differs from the earlier studies in that we treated LPS- or cytokine-stimulated cells with AA and LA whereas in earlier studies monocytes were treated with AA alone49 or pretreated with LA before the addition of LPS.60

The data presented in the manuscript clearly show that HNE-mediated increased TF activity at the cell surface appears to stem from increased PS exposure on the cell surface as HNE treatment was found to increase prothrombinase activity and annexin V binding to the cell surface. Consistent with the notion that increased PS exposure following HNE treatment is responsible for increased TF activity, annexin V treatment inhibited HNE-mediated increase in TF coagulant activity. Since unperturbed THP-1 cells, but not unperturbed endothelial cells, contained traces of TF protein on their cell surface, HNE-induced PS exposure increased basal TF activity in unperturbed THP-1 cells but not in unperturbed endothelial cells.

It may be pertinent to note here that a number of studies showed that various chemotherapy drugs, such as anthracyclines, increased the procoagulant activity in endothelial cells and monocytes through exposure of PS.62–66 Although the increased procoagulant activity observed in endothelial cells was related to PS, it was independent of TF activity.62, 64 However, increased procoagulant activity seen in THP-1 cells following anthracycline treatment was the result of increased TF activity associated with increased PS exposure on the cell surface.66 These data are consistent with our present observation, i.e., increased PS exposure could enhance TF activity in THP-1 cells as they constitutively express low levels of TF antigen. In above studies, the increased TF activity and PS exposure in cells treated with cytotoxic chemotherapeutics appeared to be associated with apoptosis. Although HNE also induces apoptosis, under our experimental conditions there was no significant decrease in the number of viable cells after treatment with HNE, indicating that HNE-induced PS externalization and increased TF activity observed in the present study may be specific and distinct from PS externalization that occurs during apoptosis.

HNE has been shown to generate ROS,9, 67 which is known to modulate many cellular functions by multiple signaling pathways.68 ROS can be generated through several sources viz. NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, mitochondrial respiratory complex I and III, and nitric oxide synthase.69 Earlier studies showed that ROS generated by xanthine:xanthine oxidase or copper metal complex increased TF activity by increasing synthesis of TF mRNA70, 71 whereas the oxidant H2O2 increased TF activity by activating the latent TF without increasing TF mRNA.72 The effect of HNE on TF appears to be similar to that of H2O2, i.e., activating the latent TF at the cell surface. It is pertinent to note here that HNE was shown to strongly induce peroxide production and the peroxide is thought to play a crucial role in HNE-induced stress signaling pathways.73 The observation that rotenone, an inhibitor of mitochondrial respiratory complex I, and not the inhibitors of NADPH oxidase or xanthine oxidase, inhibited HNE-induced TF activity increase in THP-1 cells suggests that HNE-induced ROS generated via mitochondrial respiratory complex I may play a role in HNE-mediated TF activation in THP-1 cells. Since rotenone neither completely blocks the HNE-induced ROS generation nor TF activity increase, other cellular pathways may also contribute towards HNE-mediated ROS generation and TF activation in THP-1 cells. Rotenone was shown to completely inhibit HNE-induced ROS generation in bovine lung microvascular endothelial cells.5 However, in the present study, rotenone as well as other inhibitors tested failed to attenuate HNE-mediated ROS production and TF activation in HCAEC. This discrepancy in results could be due to potential differences in the cell models used.

Recently, Canault et al.45 showed that inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling prevented PS exposure and microparticle formation in the stored platelets. Since HNE is known to activate p38 MAPK, JNK, and ERK pathways,5, 9 we investigated the involvement of these pathways in HNE-mediated increased TF activity. Our data reveal that HNE-mediated p38 MAPK pathway activation is responsible for the PS exposure since p38 MAPK inhibitor and not JNK and ERK pathway inhibitors markedly attenuated PS exposure in THP-1 cells. Consistent with the hypothesis that HNE-induced PS exposure via p38 MAPK pathway is responsible for increased TF activity in HNE-treated cells, treatment of monocytic cells with the p38 MAPK inhibitor markedly reduced the HNE-induced TF activity increase in THP-1 cells. At present, it is unclear whether HNE-induced ROS generation plays a role in p38 MAPK activation since rotenone, which inhibited the HNE-induced ROS generation significantly, but not completely, failed to suppress HNE-induced p38 MAPK activation. In contrast to that observed in THP-1 cells, p38 MAPK inhibitor had no effect on HNE-mediated increased TF activity in HCAEC, indicating that the mechanism by which HNE increases TF activity in endothelial cells may differ from that of monocytes.

In addition to the above described mechanisms, HNE can also modulate various cellular functions by depleting the cellular glutathione (GSH).57 GSH is an important intracellular antioxidant and its depletion is associated with cardiovascular diseases.74 HNE generated in cells can be detoxified by glutathione S-transferases (GSTs)75 or by thiol protectants like NAC and MPG.5 Complete abolishment of HNE-mediated increase in TF activity by NAC and MPG suggests that cellular glutathione levels regulate TF activity indirectly. NAC was also shown to inhibit functional and antigenic expression of TF in human monocytes.76 Since cells were treated with NAC after 3 h of stimulation with LPS and NAC treatment had no effect on LPS-induced TF expression per se, our data suggest that NAC inhibited HNE-mediated effects through its thiol protectant ability to detoxify HNE by forming GS-HNE.

Microparticles shed by activated and apoptotic cells play a major role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases.77 MPs derived from vascular cells, blood peripheral cells, as well as apoptotic cells sequestered within the atherosclerotic plaque are known to be reservoirs of TF activity, which can promote coagulation after plaque rupture.78 TF MPs are detected in patients with atherosclerosis.79 Similarly, increased concentrations of HNE were found in atherosclerotic lesions.80 These findings coupled with our present observation that HNE increases the generation of TF bearing microparticles, suggest that HNE can play a crucial role in the development of thrombotic disorders associated with atherosclerosis by release of TF-positive MP from endothelial cells that are activated by pathologic stimuli or SMC and fibroblasts that constitutively express TF. HNE is also known to impair endothelial barrier function by down regulating cell adhesion proteins.5 Under such compromised conditions, MPs released from underlying fibroblasts can come into the circulation and activate systemic thrombosis.

In summary, the results presented herein show that HNE, one of the most abundant reactive aldehydes generated from oxidation of ω6 fatty acids, is capable of increasing the activity of TF in both monocytic cells and endothelial cells. HNE induces PS externalization, which is responsible for increased TF activity at the cell surface, in monocytic cells through a novel mechanism involving the activation of p38 MAPK pathway. Further studies are needed to elucidate intracellular signaling pathways that lead HNE-induced p38 MAPK activation to PS externalization and to determine the relevance of the HNE-induced TF activation in thrombotic complications associated with atherosclerosis and other diseases where HNE can be produced and to elucidate mechanistic details.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

This study identifies a novel mechanism by which a lipid peroxidation product, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, enhances the activity of a procoagulant factor, tissue factor, on cell surfaces of monocytic and endothelial cells. These findings may have relevance in understanding how reactive products generated in atherosclerosis could cause thrombotic disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to James H. Morrissey, University of Illinois College of Medicine, Urbana, IL for providing TF hybridomas, and Walter Kisiel, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM for providing FVIIa. We thank Galina Florova for her assistance in using fluorescence spectrophotometer.

Source of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL1074830 and HL58869 (to LVMR).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Uchida K. Role of reactive aldehyde in cardiovascular diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1685–1696. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yin H, Xu L, Porter NA. Free radical lipid peroxidation: mechanisms and analysis. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5944–5972. doi: 10.1021/cr200084z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strohmaier H, Hinghofer-Szalkay H, Schaur RJ. Detection of 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) as a physiological component in human plasma. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1995;11:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(94)00027-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esterbauer H, Gebicki J, Puhl H, Jurgens G. The role of lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in oxidative modification of LDL. Free Radic Biol Med. 1992;13:341–390. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(92)90181-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Usatyuk PV, Parinandi NL, Natarajan V. Redox regulation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-mediated endothelial barrier dysfunction by focal adhesion, adherens, and tight junction proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35554–35566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catala A. Lipid peroxidation of membrane phospholipids generates hydroxy-alkenals and oxidized phospholipids active in physiological and/or pathological conditions. Chem Phys Lipids. 2009;157:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattson MP. Roles of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal in obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and associated vascular and neurodegenerative disorders. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadkarni DV, Sayre LM. Structural definition of early lysine and histidine adduction chemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:284–291. doi: 10.1021/tx00044a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchida K. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal: a product and mediator of oxidative stress. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:318–343. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen DR, Doorn JA. Reactions of 4-hydroxynonenal with proteins and cellular targets. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:937–945. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poli G, Schaur RJ, Siems WG, Leonarduzzi G. 4-hydroxynonenal: a membrane lipid oxidation product of medicinal interest. Med Res Rev. 2008;28:569–631. doi: 10.1002/med.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poli G, Schaur RJ. 4-Hydroxynonenal in the pathomechanisms of oxidative stress. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:315–321. doi: 10.1080/713803726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dianzani MU. 4-hydroxynonenal from pathology to physiology. Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leonarduzzi G, Robbesyn F, Poli G. Signaling kinases modulated by 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1694–1702. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yla-herttuala S, Palinski W, Rosenfeld ME, Parthasarathy S, Carew TE, Butler S, Witztum JL, Steinberg D. Evidence for the presence of oxidatively modified low density lipoprotein in atherosclerotic lesions of rabbit and man. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1086–1095. doi: 10.1172/JCI114271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurgens G, Chen Q, Esterbauer H, Mair S, Ledinski G, Dinges HP. Immunostaining of human autopsy aortas with antibodies to modified apolipoprotein B and apoprotein(a) Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1689–1699. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.11.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbrecher UP, Lougheed M, Kwan WC, Dirks M. Recognition of oxidized low density lipoprotein by the scavenger receptor of macrophages results from derivatization of apolipoprotein B by products of fatty acid peroxidation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:15216–15223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoff HF, O’Neil J, Chisolm GM, III, Cole TB, Quehenberger O, Esterbauer H, Jurgens G. Modification of low density lipoprotein with 4-hydroxynonenal induces uptake by macrophages. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:538–549. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Go YM, Halvey PJ, Hansen JM, Reed M, Pohl J, Jones DP. Reactive aldehyde modification of thioredoxin-1 activates early steps of inflammation and cell adhesion. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1670–1681. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapaport SI, Rao LVM. The tissue factor pathway: How it has become a “prima ballerina”. Thromb Haemost. 1995;74:7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleck RA, Rao LV, Rapaport SI, Varki N. Localization of human tissue factor antigen by immunostaining with monospecific, polyclonal anti-human tissue factor antibody. Thromb Res. 1990;59:421–437. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drake TA, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Selective cellular expression of tissue factor in human tissues. Implications for disorders of hemostasis and thrombosis. Am J Pathol. 1989;134:1087–1097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contrino J, Hair G, Kreutzer DL, Rickles FR. In situ detection of tissue factor in vascular endothelial cells: correlation with the malignant phenotype of human breast disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osterud B, Flaegstad T. Increased tissue thromboplastin activity in monocytes of patients with meningococcal infection: related to an unfavourable prognosis. Thromb Haemost. 1983;49:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suefuji H, Ogawa H, Yasue H, Kaikita K, Soejima H, Motoyama T, Mizuno Y, Oshima S, Saito T, Tsuji I, Kumeda K, Kamikubo Y, Nakamura S. Increased plasma tissue factor levels in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1997;134:253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreno PR, Bernardi VH, Lopez-Cuellar J, Murcia AM, Palacios IF, Gold HK, Mehran R, Sharma SK, Nemerson Y, Fuster V, Fallon JT. Macrophages, smooth muscle cells, and tissue factor in unstable angina. Implications for cell-mediated thrombogenicity in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 1996;94:3090–3097. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drake TA, Hannani K, Fei H, Lavi S, Berliner JA. Minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces tissue factor expression in cultured human endothelial cells. Am J Path. 1991;138:601–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cabre A, Girona J, Vallve JC, Masana L. Aldehydes mediate tissue factor induction: a possible mechanism linking lipid peroxidation to thrombotic events. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198:230–236. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weis JR, Pitas RE, Wilson BD, Rodgers GM. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein increases cultured human endothelial cell tissue factor activity and reduces protein C activation. FASEB J. 1991;5:2459–2465. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.5.10.2065893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brand K, Banka CL, Mackman N, Terkeltaub RA, Fan S-T, Curtiss LK. Oxidized LDL enhances lipopolysaccharide induced tissue factor expression in human adherent monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:790–797. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneko T, Wada H, Wakita Y, Minamikawa K, Nakase T, Mori Y, Deguchi K, Shirakawa S. Enhanced tissue factor activity and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 antigen in human umbilical vein endothelial cells incubated with lipoproteins. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1994;5:385–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlichting E, Henriksen T, Lyberg T. Lipoproteins do not modulate tissue factor activity, plasminogen activator or tumor necrosis factor production induced by lipopolysaccharide stimulation of human monocytes. Scan J Clin Lab Invest. 1994;54:465–473. doi: 10.3109/00365519409085471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JC, Bennet-Cain AL, DeMars CS, Doellgast GJ, Grant KW, Jones NL, Gupta M. Procoagulant activity after exposure of monocyte-derived macrophages to minimally oxidized low density lipoprotein. Co-localization of tissue factor antigen and nascent fibrin fibers at the cell surface. Am J Path. 1995;147:1029–1040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Eijnden MMED, van Noort JT, Hollaar L, van der Laarse A, Bertina RM. Cholesterol or triglyceride loading of human monocyte-derived macrophages by incubation with modified lipoproteins does not induce tissue factor expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:384–392. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penn MS, Cui MZ, winokur AL, Bethea J, Hamilton TA, Dicorleto PE, Chisolm GM. Smooth muscle cell surface tissue factor pathway activation by oxidized low-density lipoprotein requires cellular lipid peroxidation. Blood. 2000;96:3056–3063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox JN, Smith KM, Schwartz SM, Gordon D. Localization of tissue factor in the normal vessel wall and in the atherosclerotic plaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2839–2843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiruvikraman SV, Guha A, Roboz J, Taubman MB, Nemerson Y, Fallon JT. In situ localization of tissue factor in human atherosclerotic plaques by binding of digoxigenin-labeled factors VIIa and X. Lab Invest. 1996;75:451–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tremoli E, Camera M, Toschi V, Colli S. Tissue factor in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1999;144:273–283. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuster V, Fallon JT, Badimon JJ, Nemerson Y. The unstable atherosclerotic plaque: clinical significance and therapeutic intervention. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:247–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toschi V, Gallo R, Lettino M, Fallon JT, Gertz SD, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Chesebro JH, Badimon L, Nemerson Y, Fuster V, Badimon JJ. Tissue factor modulates the thrombogenicity of human atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 1997;95:594–599. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guichardant M, Taibi-Tronche P, Fay LB, Lagarde M. Covalent modifications of aminophospholipids by 4-hydroxynonenal. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;25:1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao LVM, Kothari H, Pendurthi UR. Tissue factor: Mechanisms of decryption. Front Biosci. 2012;E4:1513–1527. doi: 10.2741/477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gatidis S, Zelenak C, Fajol A, Lang E, Jilani K, Michael D, Qadri SM, Lang F. p38 MAPK activation and function following osmotic shock of erythrocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011;28:1279–1286. doi: 10.1159/000335859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canault M, Duerschmied D, Brill A, Stefanini L, Schatzberg D, Cifuni SM, Bergmeier W, Wagner DD. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation during platelet storage: consequences for platelet recovery and hemostatic function in vivo. Blood. 2010;115:1835–1842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yadav UC, Ramana KV, Awasthi YC, Srivastava SK. Glutathione level regulates HNE-induced genotoxicity in human erythroleukemia cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;227:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owens AP, III, Mackman N. Microparticles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Circ Res. 2011;108:1284–1297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morel O, Toti F, Hugel B, Bakouboula B, Camoin-Jau L, Dignat-George F, Freyssinet JM. Procoagulant microparticles: disrupting the vascular homeostasis equation? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2594–2604. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000246775.14471.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cadroy Y, Dupouy D, Boneu B. Arachidonic acid enhances the tissue factor expression of mononuclear cells by the cyclo-oxygenase-1 pathway: beneficial effect of n-3 fatty acids. J Immunol. 1998;160:6145–6150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swystun LL, Mukherjee S, Levine M, Liaw PC. The chemotherapy metabolite acrolein upregulates thrombin generation and impairs the protein C anticoagulant pathway in animal-based and cell-based models. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:767–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mackman N. Role of tissue factor in hemostasis, thrombosis, and vascular development. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1015–1022. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130465.23430.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Semeraro N, Colucci M. Tissue factor in health and disease. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:759–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shao B, Heinecke JW. HDL, lipid peroxidation, and atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:599–601. doi: 10.1194/jlr.E900001-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Esterbauer H, Wag G, Puhl H. Lipid peroxidation and its role in atherosclerosis. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:566–576. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van KF, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C, Dippel DW, Koudstaal PJ. Platelet activation and lipid peroxidation in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1997;28:1557–1563. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.8.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Halliwell B. Lipid peroxidation, antioxidants and cardiovascular disease: how should we move forward? Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:410–418. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gueraud F, Atalay M, Bresgen N, Cipak A, Eckl PM, Huc L, Jouanin I, Siems W, Uchida K. Chemistry and biochemistry of lipid peroxidation products. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:1098–1124. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2010.498477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leonarduzzi G, Chiarpotto E, Biasi F, Poli G. 4-Hydroxynonenal and cholesterol oxidation products in atherosclerosis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49:1044–1049. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Negre-Salvayre A, Coatrieux C, Ingueneau C, Salvayre R. Advanced lipid peroxidation end products in oxidative damage to proteins. Potential role in diseases and therapeutic prospects for the inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:6–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lale A, Herbert JM. Polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce pyrogen-induced tissue factor expression in human monocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48:429–431. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riahi Y, Cohen G, Shamni O, Sasson S. Signaling and cytotoxic functions of 4-hydroxyalkenals. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E879–E886. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00508.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fu Y, Zhou J, Li H, Cao F, Su Y, Fan S, Li Y, Wang S, Li L, Gilbert GE, Shi J. Daunorubicin induces procoagulant activity of cultured endothelial cells through phosphatidylserine exposure and microparticles release. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:1235–1241. doi: 10.1160/TH10-02-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swystun LL, Shin LY, Beaudin S, Liaw PC. Chemotherapeutic agents doxorubicin and epirubicin induce a procoagulant phenotype on endothelial cells and blood monocytes. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:619–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lechner D, Kollars M, Gleiss A, Kyrle PA, Weltermann A. Chemotherapy-induced thrombin generation via procoagulant endothelial microparticles is independent of tissue factor activity. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2445–2452. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma L, Francia G, Viloria-Petit A, Hicklin DJ, du MJ, Rak J, Kerbel RS. In vitro procoagulant activity induced in endothelial cells by chemotherapy and antiangiogenic drug combinations: modulation by lower-dose chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5365–5373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boles JC, Williams JC, Hollingsworth RM, Wang JG, Glover SL, Owens AP, III, Barcel DA, Kasthuri RS, Key NS, Mackman N. Anthracycline treatment of the human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 increases phosphatidylserine exposure and tissue factor activity. Thromb Res. 2012;129:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yun MR, Park HM, Seo KW, Lee SJ, Im DS, Kim CD. 5-Lipoxygenase plays an essential role in 4-HNE-enhanced ROS production in murine macrophages via activation of NADPH oxidase. Free Radic Res. 2010;44:742–750. doi: 10.3109/10715761003758122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Forman HJ, Fukuto JM, Miller T, Zhang H, Rinna A, Levy S. The chemistry of cell signaling by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and 4-hydroxynonenal. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;477:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bae YS, Oh H, Rhee SG, Yoo YD. Regulation of reactive oxygen species generation in cell signaling. Mol Cells. 2011;32:491–509. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0276-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golino P, Ragni M, Cirillo P, Avvedimento VE, Feliciello A, Esposito N, Scognamiglio A, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G, Condorelli M, Chiariello M, Ambrosio G. Effects of tissue factor induced by oxygen free radicals on coronary flow during reperfusion. Nat Med. 1996;2:35–40. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crutchley DJ, Que BG. Copper-induced tissue factor expression in human monocytic THP-1 cells and its inhibition by antioxidants. Circulation. 1995;92:238–243. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Penn MS, Patel C, Cui MZ, Dicorleto PE, Chisolm GM. LDL increases inactive tissue factor on vascular smooth muscle cell surfaces. Hydrogen peroxide activates latent cell surface tissue factor. Circulation. 1999;99:1753–1759. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uchida K, Shiraishi M, Naito Y, Torii Y, Nakamura Y, Osawa T. Activation of stress signaling pathways by the end product of lipid peroxidation. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is a potential inducer of intracellular peroxide production. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2234–2242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mills BJ, Weiss MM, Lang CA, Liu MC, Ziegler C. Blood glutathione and cysteine changes in cardiovascular disease. J Lab Clin Med. 2000;135:396–401. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2000.105976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Awasthi YC, Yang Y, Tiwari NK, Patrick B, Sharma A, Li J, Awasthi S. Regulation of 4-hydroxynonenal-mediated signaling by glutathione S-transferases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brisseau GF, Dackiw AP, Cheung PY, Christie N, Rotstein OD. Posttranscriptional regulation of macrophage tissue factor expression by antioxidants. Blood. 1995;85:1025–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.VanWijk MJ, VanBavel E, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Microparticles in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;59:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00367-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leroyer AS, Isobe H, Leseche G, Castier Y, Wassef M, Mallat Z, Binder BR, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Cellular origins and thrombogenic activity of microparticles isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:772–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mallat Z, Benamer H, Hugel B, Benessiano J, Steg PG, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Elevated levels of shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in the peripheral circulating blood of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2000;101:841–843. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Napoli C, D’Armiento FP, Mancini FP, Postiglione A, Witztum JL, Palumbo G, Palinski W. Fatty streak formation occurs in human fetal aortas and is greatly enhanced by maternal hypercholesterolemia. Intimal accumulation of low density lipoprotein and its oxidation precede monocyte recruitment into early atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2680–2690. doi: 10.1172/JCI119813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.