The first time Laura Shaver injected naloxone into a fellow drug user to save his life, she was crouched in a tent in the mountains outside Nelson, British Columbia. Friends in a nearby tent had awoken her with news that one of their companions had overdosed on methadone. Grabbing her flashlight, a bottle of naloxone and a clean syringe, Shaver raced to help.

The man had been smoking cocaine and drinking alcohol and methadone. His lips were blue and he wasn’t breathing. Although she has no formal medical education, Shaver was fresh from training by the BC Centre for Disease Control on how to intervene in opioid drug overdoses. Since 2012, the BC Take Home Naloxone program has trained more than 575 opioid drug users, family and friends and service providers and distributed more than 440 kits to prevent overdose deaths.

Holding the flashlight under her chin, Shaver jabbed the syringe into the man’s leg. She began breathing into his mouth and pumping his chest. Within seconds, he came around, but then lapsed into unconsciousness again. Shaver and another friend with medical training took turns readministering the naloxone and performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation until an ambulance finally made it to their remote location.

Once in hospital, after further administrations of naloxone, the man survived. For Shaver, who is on the board of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), the intervention was the first of 10 times she has administered naloxone. The medication, which works in two to five minutes, forces opioids such as heroin, methadone, oxycodone and fentanyl off the receptors in the brain and restores breathing. The drug works for 30–90 minutes, so overdoses may continue if people don’t get additional medical treatment.

BC’s Take Home Naloxone program is one of just four in Canada, the first of which began in Edmonton, Alberta, in 2005. In 2011, Toronto Public Health in Ontario launched its POINT (Preventing Overdose in Toronto) program. POINT has so far distributed 900 kits and collected reports of 115 people administering naloxone successfully, says Chantel Marshall, a health promotion consultant with Toronto Public Health.

The BC Centre for Disease Control’s harm reduction office has documented 45 overdose reversals since they began distributing naloxone kits

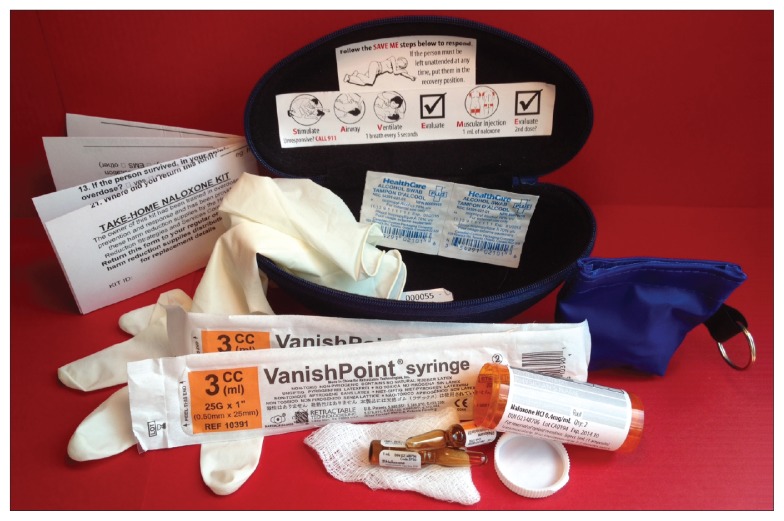

Image courtesy of Harm Reduction Program, BC Centre for Disease Control

Ottawa Public Health in Ontario created the Peer Overdose Prevention Program (POPP) that launched the same day as BC began its province-wide program, on Aug. 31, 2012. All the programs train active users of opioids (prescription or nonprescription) and their family and friends. Program administrators can provide naloxone only to users, via a prescription, but they train anyone who might witness an overdose on how to use the drug’s accompanying kit.

“Eighty-five percent of overdoses happen in the company of others, so when we are training people in the use of naloxone, it’s not just for them, it’s for other people as well,” says Dr. Jane Buxton, head of the BC Centre for Disease Control’s harm reduction office.

The program is saving lives, says Buxton, who has documented 45 overdose reversals since they began distributing naloxone kits. She views the program as a harm reduction tool and a cost-effective approach to opioid safety. In 2009, there were 70 deaths in BC involving prescription opioid medication, and 259 people died in 2012 from using illicit drugs. Take Home Naloxone has now distributed kits to 30 clinics, pharmacies and doctors’ offices across BC, as well as to Vancouver’s Insite supervised injection site. “Not only does it not increase the amount of drugs used, but people who have been trained are more safety conscious and are at less risk of an overdose,” says Buxton.

Despite the evidence that distributing the kits work, naloxone is not available on all provincial formularies. In Ontario, it is not listed on the formulary or available through the province’s Exceptional Access Program. That means organizations that want to distribute naloxone kits have to buy the medication from provinces or manufacturers and pass it out themselves, says POINT’s Marshall. She describes that as a barrier and would like to see naloxone kits available for every doctor to dispense.