Abstract

Background:

Greater awareness of sleep-disordered breathing and rising obesity rates have fueled demand for sleep studies. Sleep testing using level 3 portable devices may expedite diagnosis and reduce the costs associated with level 1 in-laboratory polysomnography. We sought to assess the diagnostic accuracy of level 3 testing compared with level 1 testing and to identify the appropriate patient population for each test.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies of level 3 versus level 1 sleep tests in adults with suspected sleep-disordered breathing. We searched 3 research databases and grey literature sources for studies that reported on diagnostic accuracy parameters or disease management after diagnosis. Two reviewers screened the search results, selected potentially relevant studies and extracted data. We used a bivariate mixed-effects binary regression model to estimate summary diagnostic accuracy parameters.

Results:

We included 59 studies involving a total of 5026 evaluable patients (mostly patients suspected of having obstructive sleep apnea). Of these, 19 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The estimated area under the receiver operating characteristics curve was high, ranging between 0.85 and 0.99 across different levels of disease severity. Summary sensitivity ranged between 0.79 and 0.97, and summary specificity ranged between 0.60 and 0.93 across different apnea–hypopnea cut-offs. We saw no significant difference in the clinical management parameters between patients who underwent either test to receive their diagnosis.

Interpretation:

Level 3 portable devices showed good diagnostic performance compared with level 1 sleep tests in adult patients with a high pretest probability of moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea and no unstable comorbidities. For patients suspected of having other types of sleep-disordered breathing or sleep disorders not related to breathing, level 1 testing remains the reference standard.

Undiagnosed sleep-disordered breathing places a substantial burden on patients, families, health care systems and society.1 Sleep fragmentation and recurrent hypoxemia cause daytime sleepiness and impaired concentration, which increase the risk of motor vehicle collisions and occupational accidents.2–7 In addition, sleep-disordered breathing is associated with hypertension, stroke, cardiovascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes,8–12 all of which involve greater use of health care resources.13–17

Obstructive sleep apnea is the most common type of sleep-disordered breathing. Narrowing of the upper airway during inspiration results in episodes of apnea (breathing cessation for at least 10 seconds), hypopnea (reduced airflow), oxygen desaturation and arousal from sleep due to respiratory effort.18 Clinical signs and symptoms include snoring, reports of nocturnal apnea, gasping or choking witnessed by a partner, daytime sleepiness, morning headaches and inability to concentrate. Patients with obesity or cardiovascular disease are at increased risk.19

The severity of obstructive sleep apnea is usually graded using the apnea–hypopnea index (the mean number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep) as follows: mild (5–14), moderate (15–29) and severe (≥ 30).18,20

Other, less common types of sleep-disordered breathing include upper airway resistance syndrome, obesity hyperventilation syndrome, central sleep apnea, and nocturnal hypoventilation/hypoxemia secondary to cardiopulmonary or neuromuscular disease. It is not uncommon for patients to have more than 1 type of sleep-disordered breathing.

Estimates of the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing vary depending on the population (e.g., by sex, age and comorbidities).21 According to the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study, values in American adults (aged 30–60 yr) are 24% for men and 9% for women.1 A Canadian survey found a self-reported prevalence of sleep apnea of 3% among adults more than 18 years of age, and 5% among those more than 45 years of age.22 As the population ages and rates of obesity increase, the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing is climbing.1,19,23,24 Given its clinical implications, accurate diagnosis and treatment of the condition are critical.

Level 1 sleep testing, or polysomnography, requires an overnight stay in a sleep laboratory with a technician in attendance. It captures a minimum of 7 channels of data (but typically ≥ 16), including respiratory, cardiovascular and neurologic parameters, to produce a comprehensive picture of sleep architecture. Level 1 is considered the reference standard for diagnosing all types of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep disorders.19,25–27 However, limited facilities and the growing demand for sleep studies have resulted in long wait times.28 Level 2 sleep testing uses level 1 equipment, but is performed without a technician in attendance.

Level 3 testing uses portable monitors that allow sleep studies to be done at the patient’s home or elsewhere. This option was introduced as a more accessible and less expensive alternative to in-laboratory polysomnography. Level 3 devices record at least 3 channels of data (e.g., oximetry, airflow, respiratory effort). Unlike level 1, level 3 testing cannot measure the duration of sleep, the number of arousals or sleep stages, nor can it detect nonrespiratory sleep disorders.27,29 Level 4 devices are also portable, but they capture less data — usually only 1 or 2 channels.27,30

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of the widely used level 3 portable monitors to in-laboratory polysomnography, and to determine the subpopulations of patients whose conditions might be most appropriately diagnosed with each test.

Methods

Literature search

We performed a comprehensive literature search of PubMed (MEDLINE and non-MEDLINE sources), the Cochrane Library and Embase for studies that compared level 3 to level 1 tests for the diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing in adults (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130952/-/DC1). We limited our search to English-language studies from 2007 to March 2012, with monthly updates from PubMed until March 2013. We also included studies from a previous systematic review prepared by our research unit, which covered the literature from 2004 to 2009. Consequently, this review covers the literature from 2004 to March 2013. We determined our date limit based on several previous Canadian and American assessments that examined the earlier literature.31–40

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts to identify possible studies for inclusion. All studies comparing level 3 with level 1 sleep tests involving adults were included if they reported on either diagnostic accuracy parameters or management after testing (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130952/-/DC1). We followed PICOS (Patients, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes and Study design) criteria to include or exclude studies. We assessed reviewer agreement using the κ statistic.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data from included studies using a standard form. Our diagnostic accuracy parameters were sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and positive and negative likelihood ratios. We extracted safety data and technical failures from all of the studies that reported these parameters. Our clinical management parameters were acceptance of continuous positive airway pressure treatment, treatment adherence, mechanical estimates of residual apnea–hypopnea index, mean machine pressure difference between patients whose diagnoses were made with the 2 different tests, quality of life and functional status as measured by clinical sleepiness questionnaires (usually the Epworth Sleepiness Scale).

Disagreements were discussed and resolved between the reviewers. No third-party adjudication was needed.

Quality assessment

We used the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool, which assesses bias (internal validity) and applicability (external validity) in multiple domains: flow and timing, reference-standard test, index test and patient selection.41,42

Statistical analysis

We pooled patient characteristics (age, body mass index [BMI] and score on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale) to obtain weighted averages. We extracted and grouped comorbidities. We presented technical failures and safety data as frequencies and proportions.

Because studies reported level 3 test performance at different apnea–hypopnea index severity levels, we examined diagnostic accuracy parameters in all studies to determine the overall ranges. We examined patterns at different severity levels in studies that reported multiple index cut-offs.

We performed a meta-analysis using a bivariate mixed-effects binary regression model. The model estimates the amount of between-study variation in sensitivity and specificity, as well as the degree of correlation between sensitivity and specificity through random effects, and uses the logit sensitivity and specificity to draw the summary ROC curves. This model requires the primary parameters of true-positive, false-positive, true-negative and false-negative. We included studies if they reported the parameters required for the model. If such parameters were not reported, we calculated them from the data provided, where possible. We estimated summary diagnostic accuracy parameters.43–45 We assessed overall heterogeneity using the Q statistic. When heterogeneity was significant, we quantified it using the I2 statistic. We estimated the summary ROC curves at different apnea–hypopnea severity levels. We performed all analyses using Stata SE version 12.

We conducted a subgroup sensitivity analysis to identify changes in diagnostic accuracy when studies that included only patients with comorbidities were removed from the analysis.

Results

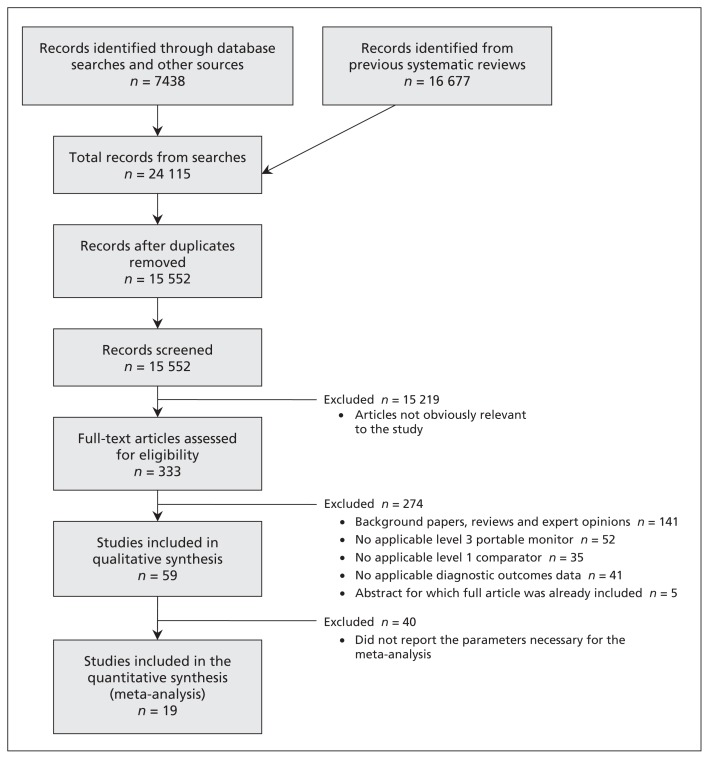

We included 59 comparative studies (15 abstracts, 44 full-text articles) involving 5044 patients (5026 of whom were evaluable) in our analysis (Figure 1). The κ statistic showed reviewer agreement (0.86).

Figure 1:

Selection of studies for inclusion in the review and meta-analysis.

We classified the included studies as “combination” studies (10 studies involving 572 evaluable patients, in which the patients underwent simultaneous in-laboratory level 3 and level 1 tests, followed by an at-home level 3 test), “simultaneous” studies (20 studies involving 1152 evaluable patients, in which the patients underwent simultaneous in-laboratory level 3 and level 1 tests) and “separate” studies (29 studies involving 3302 evaluable patients, in which an at-home level 3 test and an in-laboratory level 1 test were conducted, either with the same patients or on 2 different arms) (Table 1).46–104

Table 1:

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Study design and level 3 device used | Patient population | Outcome measures | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Eligibility criteria | ||||

| Inclusions | Exclusions | ||||

| Combination studies (simultaneous and separate) | |||||

| Abraham et al.46 | Design: cohort Location: USA/UK No. of sites: 4 Device: ClearPath Nx-301 Channels: 3 |

No. of patients: 50 Sex: 34 M, 16 F Mean age: 55.5 ± 12.8 (range 23–78) yr Mean BMI: 32.6 ± 6.5 (range 19–48) Mean ESS: 10.6 ± 4.4 (1–23) Comorbidities: heart failure (LVEF ≤ 35%) |

Stable New York Heart Association class III heart failure | Presence of cerebrovascular, neurovascular or terminal disease; severe COPD; known dermatologic condition or allergy to sensors or medical adhesives; documented MI within 6 wk of study | Diagnostic accuracy, adverse events, technical failures |

| Ayappa et al.47 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: ARES Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 102 (80 patients, 22 controls)* Sex: 69 M, 28 F Mean age: 44 (range 19–74) yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 28.7 (range 19–70) Mean ESS: 8.7 |

Suspected SDB, healthy volunteers for control | Inability to read English, inability to wear level 3 device on forehead | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, adverse events, technical failures |

| Garcia-Diaz et al.48 | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: Apnoescreen II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 65* Sex: 54 M, 8 F Mean age: 54 ± 10.4 yr Comorbidities: hypertension (27), cardiovascular comorbidity (9) Mean BMI: 30.1 ± 3.9 Mean ESS: 12 ± 3.7 |

NR | Physical or mental impairment | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, adverse events, technical failures |

| Kuna et al.49 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 39 Sex: M Mean age: 54.0 ± 9.6 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 35.8 ± 7.0 Mean ESS: NR |

Suspected sleep apnea | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Kushida et al.50 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: PMP-300E Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 11 Sex: 7 M, 4 F Mean age: 42.1 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 26.1 Mean ESS: 8.1 |

Age ≥ 18 yr, suspected OSA | NR | Diagnostic agreement |

| Polese et al.51 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Brazil No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 43 Sex: 19 M, 24 F Mean age: mean: 70 ± 5 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 30 ± 6 Mean ESS: 9 ± 7 |

Age ≥ 65 yr, suspected OSA | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Santos-Silva et al.52 | Design: cohort Location: Brazil No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 82* Sex: 46 M, 34 F Mean age: 47 ± 14 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 28 ± 5 Mean ESS: 10.4 ± 5.8 |

Age ≥ 21 yr, suspected OSA, ability to provide consent | Suspected other SDB, severe or unstable comorbid conditions, receiving oxygen or mechanical ventilation, neurologic disorders, sedative or hypnotic | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, adverse events, technical failures |

| Smith et al.53 | Design: cohort Location: UK No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 20 Sex: 14 M, 6 F Mean age: 61 ± 10 Comorbidities: congestive heart failure Mean BMI: 29 ± 6 Mean ESS: 8 ± 4 |

Informed consent, congestive heart failure, age 18–80 yr | None | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Tiihonen et al.54 | Design: cohort Location: Finland No. of sites: 1 Device: “novel device” Channels: 8 |

No. of patients: 19 Sex: 11 M, 8 F Mean age: 46.8 ± 12.7 yr Mean BMI: 31.4 ± 10.3 Comorbidities: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Suspected OSAS | NR | Diagnostic agreement |

| Tonelli de Oliveria et al.55 | Design: cohort Location: Brazil No. of sites: 1 Device: Somnocheck Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 157* Sex: 111 M, 38 F Mean age: 45 ± 12 yr Comorbidities: hypertension Mean BMI: 29.2± 5.5 Mean ESS: 11 ± 5 |

Age > 18 yr | Pregnancy, severe comorbidity (cancer, heart failure, etc.), difficulties that would interfere with examinations, residence outside hospital catchment area | Diagnostic accuracy, technical failures |

| Simultaneous studies | |||||

| Amir et al.56 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Morpheus Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 55* Sex: 36 M, 17 F Mean age: 47.8 ± 11.3 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 32.04 ± 7.9 (median 30.6) Mean ESS: NR |

Age 21–80 yr | Pacemaker, COPD, and inability to undergo the test | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Bajwa et al.57 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Alice PDx Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 7 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

NR | NR | Diagnostic agreement |

| Candela et al.58 | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: BITMED NGP140 Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 103* Sex: 72 M, 20 F Mean age: 52.4 ± 11.8 yr Comorbidities: hypertension (37), COPD (8), observed apnea (78), excessive daytime sleepiness (70) Mean BMI: 31.8 ± 6.6 Mean ESS: 11.2 ± 4.8 |

Suspected SDB | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Cheliout-Heraut et al.59 | Design: cohort Location: France/Belgium No. of sites: NR Device: Somnolter Channels: 5 |

No. of patients: 104* Sex: 60 M, 30 F Mean age: 55.4 ± 8.7 (47–70) yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 26.7 ± 7.3 (mild OSA), 28.9 ± 5.3 (moderate OSA), 29.7 ± 4.1 (severe OSA) Mean ESS: NR |

NR | Neurologic disorders, nocturnal parasomnias, restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement | Diagnostic accuracy, technical failures |

| Divo et al.60 | Design: cohort Location: Germany No. of sites: 1 Device: Apneagraph Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 14 Sex: 12 M, 2 F Mean age: 52.7 ± 14.3 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

NR | NR | Sleep indices |

| Driver et al.61 | Design: cohort Location: Canada No. of sites: 1 Device: MediByte Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 80* Sex: 30 M, 43 F Mean age: mean: 53 ± 12 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 32.2 ± 6.8 Mean ESS: NR |

Patients with high care needs, known hypercapnia and known hypoventillation | None | Diagnostic accuracy, technical failures |

| Ferre et al.62 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: Somté Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 37 Sex: 24 M, 13 F Mean age: 55.1 ± 11.5 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 27.3 ± 3.9 Mean ESS: 10 ± 8.0 |

Suspected SDB | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Goodrich et al.63 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites:1 Device: LifeShirt Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 50* Sex: 35 M, 13 F Mean age: 44 (22–69) yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Symptoms suggestive of OSA | COPD, neurologic and psychiatric disorders and significant medical conditions | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Grant et al.64 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 3 |

No. of patients: 95 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

NR | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Ng et al.65 | Design: cohort Location: Hong Kong No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 3 |

No. of patients: 90* Sex: 63 M, 17 F Mean age: 51.4 ±11.9 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 27.1 ± 4.2 Mean ESS: 9.7 ± 5.3 |

Suspected OSAS, self-reported daytime sleepiness interfering with function, and 2 of the following: choking during sleep, gasping during sleep, recurrent awakenings from sleep, unrefreshed after sleep | None | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Ng et al.66 | Design: cohort Location: Hong Kong No. of sites: 1 Device: ApneaLink Channels: 3 |

No. of patients: 50 Sex: 44 M, 6 F Mean age: 50 ± 11.8 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 27.9 ± 4.8 Mean ESS: 10.1 ± 5.5 |

Daytime sleepiness, choking, unrestful sleep, fatigue, recurrent awakening from sleep and impaired concentration | None | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Nigro et al.67 | Design: cohort Location: Argentina No. of sites: 1 Device: ApneaLink Channels: 3 |

No. of patients: 76* Sex: 47 M, 19 F Mean age: 51.5 ± 14.1 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 29.3 ± 5.4 Mean ESS: NR |

Suspicion of sleep apnea, signed informed consent, snoring with or without other symptoms, and age > 18 yr | Oxygen, CPAP | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Onder et al.68 | Design: cross-sectional Location: Turkey No. of sites: 1 Device: WatchPAT 200 Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 59* Sex: 36 M, 20 F Mean age (pooled): 42 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI (pooled): 30.5 Mean ESS: NR |

NR | Peripheral vasculopathy, pharyngeal deformity, diabetes mellitus, nephropathy, α-adrenergic receptor blockers or thoracic sympathectomy | Technical failures, sleep indices |

| Orr et al.69 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: LifeShirt Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 48 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

NR | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Su et al.70 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: SNAP Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 60 Sex: 25 M, 35 F Mean age: 45.2 ± 12.3 yr Comorbidities: hypertension Mean BMI: 35.6 ± 10.1 Mean ESS: NR |

Suspected OSAS, consecutive patient referrals | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, technical failure |

| Sullivan et al.71 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Canada No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 34 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

NR | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Takama et al.72 | Design: cohort Location: Japan No. of sites: 1 Device: Morpheus Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 99* Sex: 48 M, 35 F Mean age: 70 ± 10 yr Comorbidities: hypertension (75), dyslipidemia (66), diabetes mellitus (45), coronary artery disease (38), valvular disease (16), cardiomyopathy (16), other comorbid conditions (13) Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Patients with coronary artery disease admitted to the hospital because of anterior chest pain or heart failure who had symptoms consistent with class II or III New York Heart Association classification | NR | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Tiihonen et al.73 | Design: cohort Location: Finland No. of sites: 1 Device: APV2 remote analysis Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 10 Sex: 5 M, 5 F Mean age: 46.7 ± 12.6 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 37.3 ± 10.5 Mean ESS: NR |

Suspicion of OSA | NR | Diagnostic agreement |

| To et al.74 | Design: cohort Location: Hong Kong No. of sites: 1 Device: ARES Unicorder Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 175 Sex: 132 M, 43 F Mean age: 47.8 ± 9.8 yr (M), 52.3 ± 12.2 yr (F) Comorbidities: hypertension (85), diabetes mellitus (27), hyperlipidemia (25), fatty liver (18), cerebrovascular accident (11) Mean BMI: 28.5 ± 4.9 (M), 29.2 ± 6.0 (F) Mean ESS: 9.8 ± 5.3 (M), 12.2 ± 5.0 (F) |

Substantial sleepiness interfering with daily activities and 2 of the following symptoms: choking or gasping, recurrent awakenings, unrefreshed by sleep, daytime fatigue and impaired concentration | Pregnancy or patients who could not comply with the set-up of the device | Diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Yagi et al.75 | Design: cohort Location: Japan No. of sites: 1 Device: Apnomonitor 5 Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 22 Sex: 17 M, 5 F Mean age: 52.9 ± 13.3 (31–74) yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 25.7 ± 4.4 (18.8–39.3) Mean ESS: NR |

Suspected SAS | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Separate studies | |||||

| Alonso et al.76 | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: Edentrace II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 45 Sex: 39 M, 6 F Mean age: 52.3 ± 11 yr Comorbidities: hypertension (8), heart rhythm abnormalities (5), heart disease (3), cardiovascular accident (2), chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (1), asthma (1) Mean BMI: 28.7 ± 4 Mean ESS: 8.9 ± 3 (0–19) |

Suspected sleep apnea, residents of Burgos metropolitan area, and home suitable for study | Concomitant illness, symptoms of sleep disorders other than SAHS, occupation in which SAHS would increase occupational risk | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Andreu et al.77 | Design: RCT Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 66* Sex: 54 M, 11 F Mean age: 52 ± 10 yr Comorbidities: hypertension (32) Mean BMI: 34 ± 7 Mean ESS: ≥ 12 |

ESS > 12 | Impaired lung function, patients previously using CPAP, psychiatric diseases, neoplasm, restless leg syndrome, other dyssomnias and parasomnias | Adverse events, technical failures, clinical management |

| Askenov et al.78 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: NR Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 452 (317 level 3, 135 level 1) Sex: NR Comorbidities: NR Level 3 Mean age: 59.1 ± 0.7 yr Mean BMI: 34.7 ± 0.5 Mean ESS: 13.9 ± 0.3 Level 1 Mean age: 59.2 ± 0.9 yr Mean BMI: 34.7 ± 0.6 Mean ESS: 14.5 ± 0.5 |

Apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 5 | Patients using BPAP or PAP plus oxygen, or patients with no follow-up data | Clinical management outcomes, diagnostic agreement |

| Berry et al.79 | Design: RCT Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: WatchPAT 100 Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 106 (53 PM, 53 PSG) Comorbidities: NR PM arm Sex: 46 M, 7 F Mean age: 51.9 ± 1.7 yr Mean BMI: 34.0 ± 0.08 Mean ESS: 16.6 ± 0.47 PSG arm Sex: 47 M, 6 F Mean age: 55.1 ± 1.5 yr Mean BMI: 34.4 ± 0.9 Mean ESS: 16.2 ± 0.54 |

Excessive daytime sleepiness | Congestive heart failure, use of nocturnal oxygen, COPD, restless leg syndrome, use of narcotics, uncontrollable psychiatric disorders, night shift workers, previous treatment with CPAP, hypercapnia, neuromuscular diseases, cataplexy, use of α blockers | Clinical management outcomes |

| Bridevaux et al.80 | Design: cross-sectional Location: Switzerland No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 11 Sex: NR Mean age: 54 ± 14 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Suspected OSA | NR | Diagnostic agreement |

| Campbell et al.81 | Design: cohort Location: New Zealand No. of sites: 1 Device: Siesta Sleep System Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 31* Sex: 24 M, 6 F Mean age: 49.1 ± 13.8 (23–78) yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 31 ± 6.1 Mean ESS: 10.8 ± 4.9 (0–20) |

Age > 18 yr, residence within the hospital’s catchment area | Psychiatric disease, cardiovascular disease, limited mobility | Diagnostic accuracy, technical failures |

| Chung et al.82 | Design: cohort Location: Canada No. of sites: 2 Device: Embletta Channels: 3 |

No. of patients: 24* Sex: 11 M, 10 F Mean age: 54 ± 11 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 36 ± 9 Mean ESS: NR |

Age > 18 yr | Unwilling or unable to give informed consent, other breathing disorder | Diagnostic agreement |

| Churchward et al.83 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Australia No. of sites: 1 Device: Somté Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 20 Sex: 16 M, 4 F Mean age: 50 ± 13 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 34 ± 8.3 Mean ESS: NR |

Possible OSA | NR | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Cilli et al.84 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Turkey No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 55 Sex: 49 M, 6 F Mean age: 46 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

NR | NR | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Danzi-Soares et al.85 | Design: cohort Location: Brazil No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 79* Sex: 53 M, 17 F Mean age: 58 ± 7 yr Comorbidity: coronary artery disease Mean BMI: 27.6 Mean ESS: 7 |

Patients with coronary artery disease undergoing surgery | History of stroke and disability, clinical instability, use of supplemental oxygen | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Finkel et al.86 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: ARES Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 26 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Age > 18 yr, undergoing elective surgery | Previous diagnoses of OSA, use of home oxygen, allergy to synthetic material, inability to use sleep apnea detection device | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Fordyce et al.87 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Canada No. of sites: 1 Device: NR Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 9 Sex: 6 M, 3 F Mean age: 40.3 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 25.4 Mean ESS: NR |

History of snoring | BMI ≥ 30, adjusted neck circumference ≥ 42 cm, ESS < 10 | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Furokawa et al.88 | Design: cohort Location: Japan No. of sites: 1 Device: FM-500 Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 81 Sex: 51 M, 30 F Mean age: 64.9 ± 9.6 yr Comorbidity: hypertension Mean BMI: 25.9 ± 4.3 Mean ESS: 6.5 ± 4.1 (PSG) |

Primary hypertension | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Gjevre et al.89 | Design: cohort Location: Canada No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 47 Sex: F Mean age: 52 ± 11 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 34.9 ± 9.0 Mean ESS: 9.6 ± 4.4 (0–19) |

Age > 21 yr | Neuromuscular disease, renal failure, suspicion of SDB other than OSA, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular accidents | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement. technical failures |

| Grover et al.90 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Alice Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 5 Sex: NR Mean age: NR (range 29–59 yr) Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Polysomnography naive | NR | Diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Hernandez et al.91 | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 2 Device: respiratory polygraph Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 88 Sex: 71 M, 17 F Mean age: 50.3 ± 11.6 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 29.6 ± 4.2 Mean ESS: NR |

SAHS | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

| Kuna et al.92 | Design: RCT Location: USA No. of sites: 2 Device: Embletta Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 296* Comorbidities: NR Mean ESS: NR Level 3 Sex: 108 M, 5 F Mean age: 55.1± 10.3 yr Mean BMI: 35.0 ± 7.5 Level 1 Sex: 104 M, 6 F Mean age: 51.8 ± 10.4 yr Mean BMI: 34.2 ± 5.2 |

Suspected OSA | People with normal results on PSG or level 3 test with apnea–hypopnea index < 5, SDB other than OSA (such as central sleep apnea) | Clinical management outcomes |

| Lettieri et al.93 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust Channels: 5 |

No. of patients: 210 Comorbidities: NR Group 1 Sex: 45 M, 25 F Mean age: 50.4 ± 9.2 yr Mean BMI: 32.2 ± 4.8 Mean ESS: 14.8 ± 4.8 Group 2 Sex: 50 M, 20 F Mean age: 47.1 ± 8.0 yr Mean BMI: 30.0 ± 3.5 Mean ESS: 14.1 ± 4.2 Group 3 Sex: 48 M, 22 F Mean age: 45.5 ± 5.4 yr Mean BMI: 28.5 ± 3.0 Mean ESS: 13.9 ± 4.4 |

Meet criteria for OSA with no comorbidity | Ineligibility for home sleep testing, cardiopulmonary disorder, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, poorly controlled asthma, moderate to severe COPD or supplementary oxygen requirement | Clinical management outcomes |

| Levendowski et al.94 | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 3 Device: ARES Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 37 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Apnea–hypopnea index < 10 or > 40 based on in-home baseline study; BMI > 32; nonretropalatal airway obstruction; previous airway surgery other than nasal, adenoid or tonsil; and SDB other than OSA | None | Diagnostic agreement |

| Masa et al.95 | Design: RCT Location: Spain No. of sites: 8 Device: BreastSC20 Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 377* Sex: 263 M, 85 F Mean age: 48.7 ± 11.8 yr Comorbidities: smoking (23.9%), heart disease (37%), cerebrovascular disease (1.9%), hypertension (30.7%), depression or anxiety (23.3%) Mean BMI: 31 ± 6.6 Mean ESS: 11.6 ± 5.5 |

Age 18–70 yr, referral to sleep centre with snoring, witnessed apneas, and ESS > 10 or morning tiredness | Severe or unstable heart disease, suspected SDB other than SAHS, inability to set up portable monitor | Diagnostic accuracy, technical failures |

| Masdeu et al.96 | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: ARES Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 85 (66 patients, 19 controls) Sex: 61 M, 24 F Mean age: 42.4 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 29 Mean ESS: 7.8 |

High likelihood of OSA | Congestive heart failure, central sleep apnea | Diagnostic accuracy Diagnostic agreement |

| Nakayama et al.97 | Design: cross-sectional Location: Japan No. of sites: 1 Device: Morpheo Channels: 7 |

No. of patients: 322 Sex: M Mean age: 43.8 ± 8.4 yr Comorbidity: hypertension Mean BMI: 23.7 ± 3.1 Mean ESS: 8.1 ± 4.3 |

NR | NR | Diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Quintana-Gallego et al.98 | Design: cohort Location: Spain No. of sites: 1 Device: Apneoscreen II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 90* Sex: 65 M, 10 F Mean age: 56.1 ± 11.7 yr Comorbidities: CHF (stable heart failure due to systolic dysfunction [LVEF ≤ 45%], ischemic [42.3%], idiopathic [39.4%], other [18.3%]) Mean BMI: 28.6 ± 4.4 Mean ESS: NR |

LVEF ≤ 45% and no change in drug doses for 4 wk before the study | Instability of heart failure, acute MI in the previous 3 mo, unstable angina, or congenital heart disease | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failure |

| Rosen et al.99 | Design: RCT, Location: USA No. of sites: 7 Device: Embletta Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 373 (197 completed) Comorbidities: NR Level 3 No. of patients: 187 No. completed: 105 Sex: 107 M, 80 F Mean age: 45.6 ± 11.6 yr Mean BMI: 37 ± 8.7 Mean ESS: 14 ± 3.9 Level 1 No. of patients: 186 No. completed: 92 Sex: 118M, 68 F Mean age: 46.3 ± 12.3 yr Mean BMI: 37.5 ± 8.7 Mean ESS: 14.1 ± 3.6 |

High suspicion of OSA, ESS > 12 | Treatment with CPAP, substantial pulmonary disease, use of supplemental oxygen, awake hypercapnia or hypoventilation syndrome, respiratory or heart failure, neuromuscular disease, concerns about unsafe driving, chronic narcotic use, > 5 alcoholic drinks/d, uncontrolled psychiatric disturbance, or SDB other than OSA | Technical failures, clinical management outcomes |

| Shrivastava et al.100 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: USA No. of sites: 1 Device: Edentrace Channels: NR |

No. of patients: 99 Sex: NR Mean age: NR Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: NR |

Community-based primary care clinic population | NR | Diagnostic accuracy |

| Skomro et al.101 (Abstract) | Design: cohort Location: Canada No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 33 Sex: 27 M, 6 F Mean age: 48.3 ± 13.1 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: NR Mean ESS: 11.7 ± 4.2 |

Referral for suspected OSA, age > 18 yr | Respiratory/heart failure, presence of other sleep disorders, safety-sensitive occupation, use of hypnotics, upper airway surgery, CPAP, pregnancy | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement, technical failures |

| Skomro et al.102 | Design: prospective RCT prospective Location: Canada No. of sites: 1 Device: Embletta Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 102 (51 in each arm)* Level 3 Sex: 30 M, 14 F Mean age: 47.8 ± 11.3 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 31.4 ± 5.9 Mean ESS: 12.5 ± 3.6 Level 1 Sex: 30 M, 15 F Mean age: 49.8 ± 11.3 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 34.6 ± 6.7 Mean ESS: 12.8 ± 4.8 |

Suspicion of OSA, age > 18 yr, residence within a 1-h drive, ESS > 10 | Respiratory/heart failure, clinical features of another sleep disorder, CPAP or oxygen therapy, pregnancy and inability to provide informed consent | Clinical management outcomes |

| To et al.103 | Design: prospective RCT Location: China No. of sites: 1 Device: ARES Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 371 Comorbidities: NR Algorithm I No. of patients: 187 Sex: 138 M, 49 F Mean age: 50.87 ± 0.80 yr Mean BMI: 29.05 ± 0.32 Mean ESS: 14.5 Algorithm II (at home) No. of patients: 184 Sex: 136 M, 48 F Mean age: 49.76 ± 0.78 yr Mean BMI: 28.90 ± 0.30 Mean ESS: 13.9 |

Self-reported daytime sleepiness | Pregnancy, unwillingness to participate | Diagnostic accuracy, clinical management outcomes |

| Yin et al.104 | Design: cohort Location: Japan No. of sites: 1 Device: Stardust II Channels: 4 |

No. of patients: 90 (44 PSG) PSG Sex: 40 M, 4 F Mean age: 52.3 ± 13.5 yr Comorbidities: NR Mean BMI: 26.7 ± 5.3 Mean ESS: NR |

Suspected OSA | NR | Diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic agreement |

Note: APAP = automatic positive airway pressure, BMI = body mass index, BPAP = bilevel positive airway pressure, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure, ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale, F = female, LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction, M = male, MI = myocardial infarction, NR = not reported, OSA = obstructive sleep apnea, OSAS = obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, PAP = positive airway pressure, PAT = peripheral arterial tonometry, PM = portable monitoring, PSG = polysomnography, RCT = randomized controlled trial, SAH = sleep apnea–hypopnea, SAHS = sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome, SAS = sleep apnea syndrome, SDB = sleep-disordered breathing.

Not all patients completed the study. Results reported only for evaluable patients (i.e., those who completed the tests, had their records analyzed or who started CPAP treatment).

Patient characteristics

The included studies recruited patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130952/-/DC1). Patients were referred for sleep testing after a pretest assessment that included sleep questionnaires, history and clinical examination.

When we pooled participant characteristics from all studies, patients had a mean age of 50.8 years, a mean score of 11.6 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale and a mean BMI of 30.4. The ratio of male to female patients was 2.9 to 1. A total of 1382 comorbidities were reported, with cardiovascular conditions the most common (1080 patients, 78.1% of total comorbidities). Hypertension was the most frequently reported cardiovascular condition (574 patients), followed by stable chronic heart disease (142 patients) and coronary artery disease (113 patients). Respiratory comorbidities were limited to a single patient with asthma and 9 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (0.7% of total comorbidities).

Study characteristics

The 4 channels measured in all of the studies were nasal airflow, thoracoabdominal movement, oxygen saturation and body position.

Two studies reported adverse events with in-laboratory level 3 tests (1 hypertensive crisis, 1 pacemaker interference).46,52 One study reported sensor irritation in 27 patients.46

Technical failures affected 0.44% of patients who underwent level 1 tests, 1.30% of patients who underwent in-laboratory level 3 tests and 10.25% of patients who underwent level 3 tests at home (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130952/-/DC1).

Diagnostic accuracy of sleep tests

Among all included studies, the area under the ROC curves for at-home (6 studies) and in-laboratory (7 studies) testing showed values of 0.90 or greater at all apnea–hypopnea index cutoffs, with the exception of 2 studies that reported values of 0.79 and 0.86 at an apnea–hypopnea index of moderate or severe (≥ 15 events/h) at home, and 2 studies that reported values ranging from 0.87 to 0.89 at moderate or severe cut-offs (≥ 15, ≥ 20 and ≥ 30 events/h) in laboratory (Appendix 5, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.130952/-/DC1).

In studies reporting multiple cut-offs, with increasing disease severity, 7 of 10 at-home studies showed a decline in sensitivity and an increase in specificity, and 2 of the studies showed an increase in area under the ROC curve.46–48,52,55,81,88,89,98,104 In addition, 7 of 14 in-laboratory studies showed a decline in sensitivity and an increase in specificity, and 2 studies showed an increase in area under the ROC curve.47,48,51,52,58,61–63,65–67,69–71

We found no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups of patients in all 8 studies that reported disease management after the diagnosis by either test. None of the studies found significant differences in disease management parameters.77–79,92,93,99,102,103

In most of the studies, patients underwent both level 1 and level 3 tests to avoid the risk of internal bias due to differences between study groups. In all of the simultaneous studies, level 3 tests were scored manually by the same technician who scored the level 1 test, which may have resulted in observer bias. In contrast, most of the studies reported blinding the interpreters of level 3 tests to the level 1 test results, mitigating the risk of observer bias.

Most of the studies adequately described the tests, number of patients, recruitment methods and dropouts. Fifteen studies (only available as abstracts) had incomplete reporting of 1 or more elements (Table 2).

Table 2:

Quality appraisal of the included studies using the QUADAS-2 tool

| Study | Bias (internal validity) | Applicability concerns (external validity) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Selection of patients | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Selection of patients | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Abraham et al.46 | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Alonso Alvarez et al.76 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Amir et al.56 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Andreu et al.77 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Askenov et al.78 | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Ayappa et al.47 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Bajwa et al.57 | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Berry et al.79 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Bridevaux et al.80 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Campbell et al.81 | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Candela et al.58 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Cheliout et al.59 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Chung et al.82 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Churchward et al.83 | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Cilli et al.84 | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Danzi-Soares et al.85 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Divo et al.60 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Driver et al.61 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Ferre et al.62 | High risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Finkel et al.86 | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Fordyce et al.87 | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Furokawa et al.88 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Garcia-Diaz et al.48 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Gjevre et al.89 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Goodrich et al.63 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Grant et al.64 | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Grover et al.90 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Hernandez et al.91 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Kuna et al.49 | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Kuna et al.92 | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Kushida et al.50 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Lettieri et al.93 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Levendowski et al.94 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Masa JF et al.95 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Masdue et al.96 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Nakayama et al.97 | High risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Ng et al.65 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Ng et al.66 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Nigro et al.67 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Onder et al.68 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Orr et al.69 | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Polese et al.51 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Quintana-Gallego et al.98 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Rosen et al.99 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Santos-silva et al.52 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Shrivastava et al.100 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Skomro et al.102 | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Skomro et al.101 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Smith et al.53 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Su et al.70 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Sullivan et al.71 | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Takama et al.72 | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

|

| |||||||

| Tiihonen et al.54 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Tiihonen et al.73 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| To et al.74 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| To et al.103 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Tonelli de Oliveira et al.55 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Yagi et al.75 | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

|

| |||||||

| Yin et al.104 | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk |

Note: QUADAS-2 = Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2.

Most studies recruited patients suspected of having simple obstructive sleep apnea without comorbidities or with stable cardiovascular comorbidities. None of the studies included patients with other forms of sleep-disordered breathing (Table 2).

Results of the meta-analysis

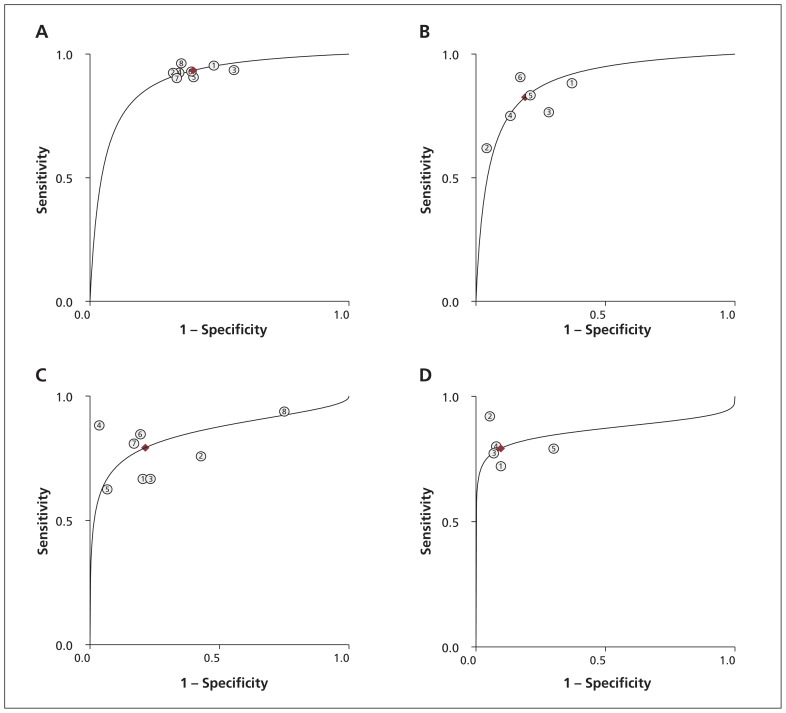

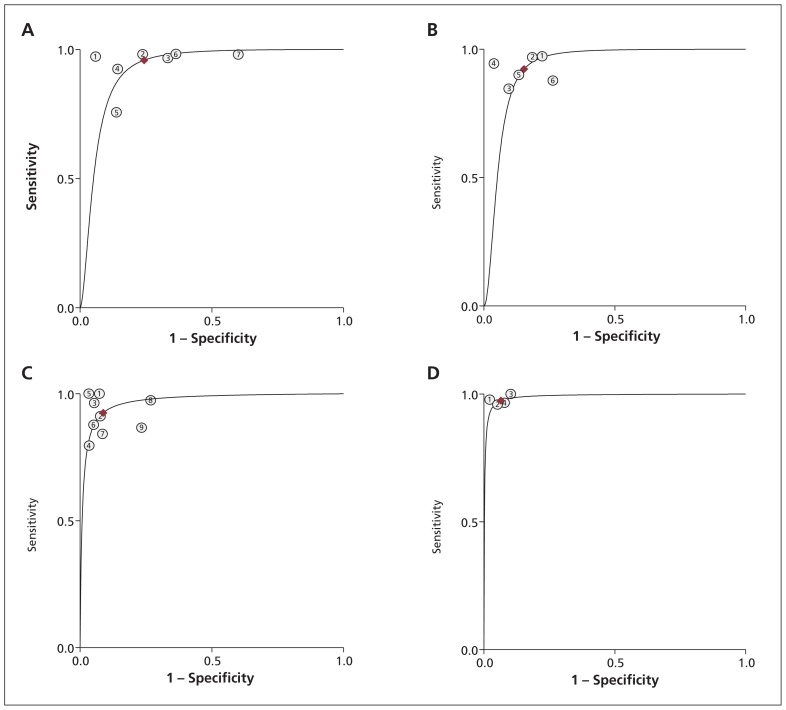

We identified 19 studies reporting the parameters needed for our meta-analysis (Table 3). Among these studies, we found moderate to high heterogeneity at a mild apnea–hypopnea index cut-off in laboratory (≥ 5 events/h) and at home (≥ 10 events/h), and at a moderate cut-off for both settings (≥ 15 events/h) (I2 53%–85%).105 Overall, diagnostic accuracy improved as disease severity increased (Figures 2 and 3).

Table 3:

Results of the meta-analysis of studies including the primary parameters of true-positive, false-positive, true-negative and false-negative

| Location, apnea–hypopnea cut-off | No. of studies | Overall heterogeneity | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Area under the ROC curve (95% CI) | Positive LR (95% CI) | Negative LR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 (95% CI) | p value for Q statistic | |||||||

| Home, ≥ 5 events/h | 846,47,52,55,84,85,89,102 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | 0.60 (0.51–0.68) | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 2.3 (1.9–2.9) | 0.11 (0.07–0.16) |

| Laboratory, ≥ 5 events/h | 747,52,61,65,67,70,118 | 85 (68–100) | 0.001 | 0.96 (0.90–0.98) | 0.76 (0.63–0.85) | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | 3.9 (2.6–6.1) | 0.05 (0.02–0.13) |

| Home, ≥ 10 events/h | 646,47,55,76,89,91 | 53 (0–100) | 0.06 | 0.83 (0.73–0.89) | 0.81 (0.70–0.89) | 0.89 (0.86–0.91) | 4.3 (2.7–7.0) | 0.22 (0.14–0.33) |

| Laboratory, ≥ 10 events/h | 647,48,58,61,65,70 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.92 (0.87–0.95) | 0.85 (0.77–0.90) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | 6.0 (4.0–8.9) | 0.09 (0.05–0.15) |

| Home, ≥ 15 events/h | 846–48,52,55,85,89,104 | 82 (62–100) | 0.002 | 0.79 (0.71–0.86) | 0.79 (0.63–0.89) | 0.85 (0.82–0.88) | 3.7 (2.1–6.7) | 0.26 (0.19–0.37) |

| Laborator, ≥15 events/h | 947,48,52,56,58,61,65,67,70 | 66 (23–100) | 0.03 | 0.92 (0.86–0.96) | 0.91 (0.85–0.95) | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) | 10.6 (6.1–18.2) | 0.08 (0.04–0.15) |

| Home, ≥ 30 events/h | 548,52,55,88,104 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.79 (0.72–0.85) | 0.90 (0.84–0.95) | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | 8.2 (4.7–14.6) | 0.23 (0.16–0.32) |

| Laboratory, ≥ 30 events/h | 448,52,58,67 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.97 (0.92–0.99) | 0.93 (0.89–0.96) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) | 14.9 (8.6–25.8) | 0.03 (0.01–0.08) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, LR = likelihood ratio, ROC = receiver operator characteristic.

Figure 2:

Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves comparing level 3 at-home sleep studies with level 1 in-laboratory studies. (A) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 5 events/h. (B) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 10 events/h. (C) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 15 events/h. (D) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 30 events/h.

Figure 3:

Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves comparing level 3 and level 1 in-laboratory sleep studies. (A) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 5 events/h. (B) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 10 events/h. (C) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 15 events/h. (D) ROC for apnea–hypopnea index ≥ 30 events/h.

Sensitivity analysis

When we removed the 3 studies that recruited only patients with comorbidities from the meta-analysis, the results of in-laboratory sleep testing remained unchanged, because the excluded studies had only been done at the patients’ homes. Sensitivity in the at-home setting showed a slight improvement, ranging from 1% to 3% at all apnea–hypopnea index cut-offs, with the exception of 10 or more events per hour (where sensitivity decreased from 83% to 81%). Specificity improved by 2% and 3% at cut-offs of 5 or more and 10 or more events per hour, respectively, but remained unchanged at cut-offs of 15 or more and 30 or more events per hour. The area under the ROC curve improved slightly (1%) at all cut-offs other than 10 or more events per hour.

Interpretation

Level 3 portable devices scored well for sensitivity (the ability of a test to correctly identify those who have the disease), and specificity (the ability of a test to correctly identify those who do not have the disease), with a trade-off of increasing specificity and decreasing sensitivity as disease severity increased. The areas under the ROC curves (a measure that combines sensitivity and specificity to show the overall discriminatory power of the test, with a value of 1 indicating perfect discrimination) confirmed the performance of level 3 devices. The performance of level 3 devices was better in the laboratory than at home — the devices had a high technical failure rate when testing was done at home. Bruyneel and colleagues reported similar rates in their study comparing level 1 in-laboratory to unattended level 1 at-home sleep studies (the latter is considered level 2 testing). The unattended level 1 studies had similar rates of technical failures, despite using full polysomnography equipment, suggesting the failures were because a sleep technician was not in attendance.106

Despite the heterogeneity we saw at some apnea–hypopnea index cut-offs in our meta-analysis, the pooled estimates of diagnostic accuracy parameters appear reliable. We used a model that accounts for this heterogeneity107–110 despite the use of different level 3 devices, which each measured the same core parameters.

The studies included in this review were designed to evaluate diagnostic accuracy rather than identify subpopulations of patients who might benefit from each test. Most patients in these studies had uncomplicated obstructive sleep apnea without unstable comorbidities. The patients were typically referred from sleep or respiratory clinics where a comprehensive pre-test evaluation had been completed, suggesting a high pretest probability of obstructive sleep apnea (e.g., symptoms such as snoring and daytime sleepiness). Family physicians play a key role in the diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing. Reuveni and colleagues discussed the need for educational programs to increase awareness among family physicians of the signs of obstructive sleep apnea.111 Such programs will likely increase testing, optimize the use of diagnostic resources and expedite treatment.112–114

Our findings confirm those of previous reviews, health technology assessments and clinical practice guidelines based on earlier evidence of portable monitor use in the diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing.25–27,31–39,115 These reviews concluded that level 3 devices are useful in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with a high pretest likelihood of having moderate to severe forms of the condition. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Canadian Sleep Society/Canadian Thoracic Society guidelines recommend that portable sleep studies be provided under the direction of health professionals with accreditation in sleep medicine and as part of a comprehensive assessment.25–27 The US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has determined that portable devices (with a minimum of 3 channels) are acceptable for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea in patients with clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of the condition.116

Limitations

We included only English-language studies in this review, therefore it is possible that relevant studies in other languages were excluded. In addition, none of the studies included patients with forms of sleep-disordered breathing other than obstructive sleep apnea, limiting the generalizability of the results to patients with other forms of sleep-disordered breathing.

Conclusion

Level 3 sleep studies are safe and convenient for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea in patients with a high pretest probability of moderate to severe forms of the condition without substantial comorbidities. Level 1 polysomnography remains the cornerstone for the diagnosis in patients suspected of having comorbid sleep disorders, unstable medical conditions or complex sleep-disordered breathing. Further studies assessing the use of portable sleep studies in patients with conditions other than obstructive sleep apnea, and in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and comorbidities, are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Babak Bohlouli, University of Alberta, Department of Medicine, for his help with screening, reviewing and abstracting the data; Ms. Sarah Ndegwa for her help with reviewing and abstracting data; and Dr. Dominic Carney for his clinical advice throughout the project.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Mohamed El Shayeb selected the studies, extracted the data, conducted the meta-analysis, analyzed the results and drafted the manuscript. Leigh-Ann Topfer conducted the literature search, and edited and revised the manuscript. Tania Stafinski helped conceive the design of the review, extracted the data, and edited and revised the manuscript. Lawrence Pawluk edited and revised the manuscript. Devidas Menon helped conceive the design of the review, extracted the data, and edited and reviewed the manuscript. All of the authors approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: Production of this work has been made possible by a financial contribution from Alberta Health and under the auspices of the Alberta Health Technologies Decision Process: the Alberta Model for Health Technology Assessment and Policy Analysis. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official policy of Alberta Health. The study sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. Burden of sleep apnea: rationale, design, and major findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study. WMJ 2009;108:246–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tregear S, Reston J, Schoelles K, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and risk of motor vehicle crash: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5:573–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellen RL, Marshall SC, Palayew M, et al. Systematic review of motor vehicle crash risk in persons with sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2006;2:193–200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurubhagavatula I, Nkwuo JE, Maislin G, et al. Estimated cost of crashes in commercial drivers supports screening and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Accid Anal Prev 2008;40:104–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulgrew AT, Nasvadi G, Butt A, et al. Risk and severity of motor vehicle crashes in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea. Thorax 2008;63:536–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AlGhanim N, Comondore VR, Fleetham J, et al. The economic impact of obstructive sleep apnea. Lung 2008;186:7–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gander P, Scott G, Mihaere K, et al. Societal costs of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. N Z Med J 2010;123:13–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:686–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronksley PE, Tsai WH, Quan H, et al. Data enhancement for co-morbidity measurement among patients referred for sleep diagnostic testing: an observational study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009;9:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hensley M, Ray C. Sleep apnoea. Clin Evid (Online) 2007. July 1;2007. pii: 2301. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young T. Rationale, design and findings from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study: toward understanding the total societal burden of sleep disordered breathing. Sleep Med Clin 2009;4:37–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seicean S, Strohl KP, Seicean A, et al. Sleep disordered breathing as a risk of cardiac events in subjects with diabetes mellitus and normal exercise echocardiographic findings. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:1214–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarasiuk A, Greenberg-Dotan S, Simon-Tuval T, et al. The effect of obstructive sleep apnea on morbidity and health care utilization of middle-aged and older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:247–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennum P, Kjellberg J. Health, social and economical consequences of sleep-disordered breathing: a controlled national study. Thorax 2011;66:560–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapur V, Blough DK, Sandblom RE, et al. The medical cost of undiagnosed sleep apnea. Sleep 1999;22:749–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahammam A, Delaive K, Ronald J, et al. Health care utilization in males with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome two years after diagnosis and treatment. Sleep 1999;22:740–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banno K, Ramsey C, Walld R, et al. Expenditure on health care in obese women with and without sleep apnea. Sleep 2009;32: 247–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strohl KP. Overview of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Jr, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2009;5:263–76 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep 1999;22:667–89 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akinnusi M, Saliba R, El-Solh AA. Emerging therapies for obstructive sleep apnea. Lung 2012;190:365–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.What is the impact of sleep apnea on Canadians? Fast facts from the 2009 Canadian Community Health Survey — sleep apnea rapid response. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennum P, Riha RL. Epidemiology of sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J 2009;33: 907–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2012;379:1341–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fleetham J, Ayas N, Bradley D, et al. Canadian Thoracic Society 2011 guideline update: diagnosis and treatment of sleep disordered breathing. Can Respir J 2011;18:25–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3:737–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blackman A, McGregor C, Dales R, et al. Canadian Sleep Society/Canadian Thoracic Society position paper on the use of portable monitoring for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea in adults. Can Respir J 2010;17:229–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flemons WW, Douglas NJ, Kuna ST, et al. Access to diagnosis and treatment of patients with suspected sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;169:668–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohsenin V. Portable monitoring for obstructive sleep apnea: the horse is out of the barn: avoiding pitfalls. Am J Med 2013; 126:e1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collop N. Portable monitoring in obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Waltham (MA): UpToDate; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 31.An assessment of sleep disordered breathing diagnosis using level I versus level III sleep studies. Final report. Edmonton (AB): Prepared for Alberta Health and Wellness by the Health Technology & Policy Unit, School of Public Health, University of Alberta; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ndegwa S, Clark M, Argaez C. Portable monitoring devices for diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea at home: review of accuracy, cost effectiveness, guidelines, and coverage in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH); 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trikalinos TA, Lau J. Home diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ); 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trikalinos TA, Lau J. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: modeling different diagnostic strategies. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea [Health Care Guideline]. 6th ed Bloomington (MN): Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balk EM, Moorthy D, Obadan NO, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults [AHRQ comparative effectiveness reviews]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ghegan MD, Angelos PC, Stonebraker AC, et al. Laboratory versus portable sleep studies: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2006; 116:859–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Polysomnography in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: an evidence-based analysis. Toronto (ON): Medical Advisory Secretariat, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2006 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gleitsmann K, Kriz H, Thielke A, et al. Sleep apnea diagnosis and treatment in adults. Final evidence report. Portland (OR): Center for Evidence-based Policy, Oregon Health and Science University for the Washington State Health Care Authority; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flemons WW, Littner MR, Rowley JA, et al. Home diagnosis of sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature. An evidence review cosponsored by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the American Thoracic Society. Chest 2003;124:1543–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:529–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huedo-Medina T, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Storrs (CT): Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention (CHIP); 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JP. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1158–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fletcher J. What is heterogeneity and is it important? BMJ 2007; 334:94–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abraham WT, Trupp RJ, Phillilps B, et al. Validation and clinical utility of a simple in-home testing tool for sleep-disordered breathing and arrhythmias in heart failure: results of the Sleep Events, Arrhythmias, and Respiratory Analysis in Congestive Heart Failure (SEARCH) study. Congest Heart Fail 2006;12:241–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayappa I, Norman RG, Seelall V, et al. Validation of a self-applied unattended monitor for sleep disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4:26–37 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.García-Díaz E, Quintana-Gallego E, Ruiz A, et al. Respiratory polygraphy with actigraphy in the diagnosis of sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome. Chest 2007;131:725–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuna ST, Seeger T, Brendel M. Intra-subject comparison of polysomnography and a type 3 portable monitor [abstract]. Sleep 2005;28(Suppl):A324 (abstract no. 0956). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kushida CA, Cardell C, Black S, et al. Comparison of a new type 3 portable monitor for OSA detection vs. in-lab polysomnography [abstract]. Sleep 2009;32(Suppl):A385 (abstract no. 1178). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polese JF, Santos SR, Sartori DE, et al. Validation of a portable monitoring systemfor the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in elderly patients [abstract]. Sleep Medicine 2009;10(Suppl 2):S22 (abstract no. 078).19647482 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Santos-Silva R, Sartori DE, Truksinas V, et al. Validation of a portable monitoring system for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 2009;32:629–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith LA, Chong DW, Vennelle M, et al. Diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing in patients with chronic heart failure: evaluation of a portable limited sleep study system. J Sleep Res 2007; 16:428–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tiihonen P, Paakkonen A, Mervaala E, et al. Design, construction and evaluation of an ambulatory device for screening of sleep apnea. Med Biol Eng Comput 2009;47:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tonelli de Oliveira AC, Martinez D, Vasconcelos LF, et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and its outcomes with home portable monitoring. Chest 2009;135:330–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amir O, Barak-Shinar D, Amos Y, et al. An automated sleep-analysis system operated through a standard hospital monitor. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6:59–63 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bajwa I, Grover S, Clawson T, Cady M. Validity of respiratory events collected from a portable monitoring device [abstract]. Sleep 2009;32(Suppl):A376 (abstract no. 1150). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Candela A, Hernandez L, Asensio S, et al. Validation of a respiratory polygraphy system in the diagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome. Arch Bronconeumol 2005;41:71–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheliout-Heraut F, Senny F, Djouadi F, et al. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: comparison between polysomnography and portable sleep monitoring based on jaw recordings. Neurophysiol Clin 2011;41:191–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morales Divo C, Selivanova O, Mewes T, et al. Polysomnography and ApneaGraph in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2009;71:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Driver HS, Pereira EJ, Bjerring K, et al. Validation of the MediByte(R) type 3 portable monitor compared with polysomnography for screening of obstructive sleep apnea. Can Respir J 2011; 18:137–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferre A, Grau M, Jurado M, et al. Evaluation of a new simplified polysomnography system for the diagnosis of sleep disordered breathing [abstract]. J Sleep Res 2008;17(Suppl 1):234 (abstract no. P441). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodrich S, Orr WC. An investigation of the validity of the Lifeshirt in comparison to standard polysomnography in the detection of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2009;10:118–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grant B. Diagnostic accuracy of home sleep studies for sleep apnea [abstract]. Sleep 2009;32(Suppl):A232 (abstract no. 713). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ng SS, Chan TO, To KW, et al. Validation of Embletta portable diagnostic system for identifying patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS). Respirology 2010;15:336–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ng SS, Chan TO, To KW, et al. Validation of a portable recording device (ApneaLink) for identifying patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Intern Med J 2009;39:757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nigro CA, Serrano F, Aimaretti S, et al. Utility of ApneaLink for the diagnosis of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Medicina (B Aires) 2010;70:53–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Onder NS, Akpinar ME, Yigit O, et al. Watch peripheral arterial tonometry in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea: influence of aging. Laryngoscope 2012;122:1409–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orr WC, Goodrich S. An investigation of the accuracy of the Lifeshirt in comparison to standard polysomnography [abstract]. Sleep 2006;29(Suppl):A348 (abstract no. 1020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Su S, Baroody FM, Kohrman M, et al. A comparison of polysomnography and a portable home sleep study in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;131:844–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sullivan GE, Morehouse R, Savoy A. Comparison of synchronized level 1 and level 3 sleep studies [abstract]. Vigilance 2009; 19(Suppl) (abstract no. P074). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takama N, Kurabayashi M. Effectiveness of a portable device and the need for treatment of mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep-disordered breathing in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Cardiol 2010;56:73–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tiihonen P, Hukkanen T, Tuomilehto H, et al. Evaluation of a novel ambulatory device for screening of sleep apnea. Telemed J E Health 2009;15:283–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.To KW, Chan WC, Chan TO, et al. Validation study of a portable monitoring device for identifying OSA in a symptomatic patient population. Respirology 2009;14:270–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yagi H, Nakata S, Tsuge H, et al. Significance of a screening device (Apnomonitor 5) for sleep apnea syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx 2009;36:176–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alonso Alvarez ML, Santos JT, Guevara JC, et al. Reliability of home respiratory polygraphy for the diagnosis of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: analysis of costs. Arch Bronconeumol 2008; 44:22–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andreu AL, Chiner E, Sancho-Chust JN, et al. Effect of an ambulatory diagnostic and treatment programme in patients with sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J 2012;39:305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Aksenov IV, Foster C, Berry RB. Management of obstructive sleep apnea: portable monitoring for diagnosis followed by treatment with auto-adjusting positive airway pressure [abstract]. Sleep 2009;32(Suppl):A183 (abstract no. 0557). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berry RB, Hill G, Thompson L, et al. Portable monitoring and autotitration versus polysomnography for the diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea. Sleep 2008;31:1423–31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bridevaux PO, Fitting JW, Fellrath JM, et al. Inter-observer agreement on apnoea hypopnoea index using portable monitoring of respiratory parameters. Swiss Med Wkly 2007;137:602–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Campbell AJ, Neill AM. Home set-up polysomnography in the assessment of suspected obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res 2011; 20:207–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chung F, Liao P, Sun Y, et al. Perioperative practical experiences in using a level 2 portable polysomnography. Sleep Breath 2011; 15:367–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Churchward TJ, O’Donoghue F, Rochford P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and cost effectiveness of home-based PSG in OSA [abstract]. Sleep Biol Rhythms 2006;4(Suppl):A11 (abstract no. 0–11). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cilli A, Erogullari I, Turhan M, et al. Comparison of Embletta portable device versus Embla for diagnosing the obstructive sleep apnea [abstract]. J Sleep Res 2006;15(Suppl 1):152 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Danzi-Soares NJ, Genta PR, Nerbass FB, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is common among patients referred for coronary artery bypass grafting and can be diagnosed by portable monitoring. Coron Artery Dis 2012;23:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Finkel KJ, Searleman AC, Tymkew H, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea among adult surgical patients in an academic medical center. Sleep Med 2009;10:753–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fordyce L, Samuels CH, Oram C, et al. A retrospective, observational study showing patients with a normal level III sleep study and normal OSA pretest probability factors may still require additional investigations [abstract]. Vigilance 2009; 19(Suppl) (abstract no. P075). [Google Scholar]

- 88.Furukawa T, Suzuki M, Funatogawa I, et al. Screening method for severe sleep-disordered breathing in hypertensive patients without daytime sleepiness. J Cardiol 2009;53:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gjevre JA, Taylor-Gjevre RM, Skomro R, et al. Comparison of polysomnographic and portable home monitoring assessments of obstructive sleep apnea in Saskatchewan women. Can Respir J 2011;18:271–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grover S, Cady M. A user-friendly device for home monitoring of sleep disorders [abstract]. Sleep 2009;32(Suppl):A371 (abstract no. 1136). [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hernández L, Torrella M, Roger N, et al. Management of sleep apnea: concordance between nonreference and reference centers. Chest 2007;132:1853–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuna ST, Gurubhagavatula I, Maislin G, et al. Noninferiority of functional outcome in ambulatory management of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:1238–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lettieri CF, Lettieri CJ, Carter K. Does home sleep testing impair continuous positive airway pressure adherence in patients with obstructive sleep apnea? Chest 2011;139:849–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Levendowski D, Steward D, Woodson BT, et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea variability measured in-lab versus in-home on sample size calculations. Int Arch Med 2009;2:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Masa JF, Corral J, Pereira R, et al. Therapeutic decision-making for sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome using home respiratory polygraphy: a large multicentric study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;184:964–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Masdeu MJ, Ayappa I, Hwang D, et al. Impact of clinical assessment on use of data from unattended limited monitoring as opposed to full-in lab PSG in sleep disordered breathing. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6:51–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]