Abstract

Introduction

Chronic ethanol consumption is associated with persistent hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection. This study explores the role of the host cellular immune response to HCV core protein in a murine model and how chronic ethanol consumption alters T-cell regulatory (Tregs) populations.

Methods

Balb/c mice were fed an isocaloric control or ethanol liquid diet. Dendritic cells (DCs) were isolated after expansion with a hFl3tL-expression plasmid and subsequently transfected with HCV core protein. Core-containing DCs (1 × 106) were subcutaneously injected (X3) in mice every 2 weeks. Splenocytes from immunized mice were isolated and stimulated with HCV core protein to measure generation of viral antigen specific Tregs, as well as secretion of IL-2, TNF-α, and IL-4. Cytotoxicity was measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from HCV core-expressing syngeneic SP2/19 myeloma cells.

Results

Splenoctyes from mice immunized with ethanol-derived and HCV core-loaded DCs exhibited significantly lower in vitro cytotoxicity compared to mice immunized with HCV core-loaded DCs derived from isocaloric pair fed controls. Stimulation with HCV core protein triggered higher IL-2 TNF-α and IL-4 release in splenocytes following immunization with core-loaded DCs derived from controls as compared to chronic ethanol fed mice. Splenocytes derived from mice immunized with core-loaded DCs isolated from ethanol-fed mice exhibited a significantly higher CD25+FOXP3+ and CD4+FOXP3+ Treg population.

Conclusions

These results suggest that immunization with HCV core-containing DCs from ethanol-fed mice induces an increase in the CD25+FOXP3+ and CD4+FOXP3+ Treg population and may suppress HCV core-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immune responses.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, immune responses, T-regulatory cells, chronic ethanol

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a single-stranded RNA virus of the Falviviridae family (1) that affects 2-3% of the world's population, causing more than 350,000 deaths per year (2). Since the discovery of this virus in 1989 (3), vaccine development has been difficult and its mechanism of action with respect to producing hepatocyte injury remains to be clarified. Ribavirin and pegylated IFN-α as well as Telaprevir and Boceprevirare currently used as therapy for this disease (4-7). Of the HCVgenotype-1-infected patients treated, however, about 20-40% will continue to exhibit viral persistence, aggravating liver injury and accelerating progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (8, 9). Further studies regarding the biology of host-viral interactions are needed in order to better understand the pathogenesis of persistent viral infection.

Hepatitis C virus has a genome size of 9.6 Kb that codes for structural (core and envelope) and nonstructural (NS2, NS3, NS4 and NS5)proteins (10). Of interest, HCV core protein plays a pathogenic role in hepatocyte apoptosis, alters lipid metabolism and activates cellular immune responses (11, 12). Its association with the ER and the mitochondria is known to increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, oxidation of glutathione pools in the mitochondria, ER stress, and to inhibit the JAK/STAT signal transduction pathway that is crucial in generating immunity (13, 14). The combination of HCV infection with chronic ethanol abuse, however, has a more deleterious and even synergistic adverse effect. Alcoholics with HCV infection are more likely to evolve viral persistence following exposure, and this interaction accelerates fibrosis development compared to abstainers with chronic HCV infection (15, 16). Liver biopsies derived from alcoholic and persistently infected HCV patients have demonstrated accelerated micro- and macrosteatosis, cell dropout, fibrosis and lymphocyte infiltration (17). Biochemical studies have revealed high level proteasome activity, lipid peroxidation, and cell injury as a consequence of oxidative stress and glutathione pool depletion; all of which appear to be enhanced by the combination of ethanol abuse and HCV infection (18-22). Other investigations have shown that generation of helper T cell(Th1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity to structural and non-structural proteins are reduced in mice consuming a chronic ethanol-containing diet (23), which can be rescued by immunizing with interleukin-2 or granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) expression plasmids. These studies have suggested that ethanol's adverse effects on HCV infection are due, in part, to alteration of immune regulation that may particularly affect the function of antigen presenting cells (APCs).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are professional APCs that take up, process and present peptides to T cells via major histocompatibility complexes (MHC)(24). Their robust function, with respect to activation of T cell mediated immune responses, makes them ideal for delivery of HCV viral proteins (25, 26). In this context, Aloman et al, utilizing a DC based immunization approach in chronically ethanol-fed mice observed a reduced cellular immune response against HCV NS5 protein compared to animals fed a control diet (18). In the present study, we have extended this approach to investigate the possible mechanism(s) for inhibition by using DC-based immunization against HCV core derived from ethanol-fed mice, to explore T cell mediated cytotoxicity, cytokine release and regulatory cell activation.

Materials and Methods

Media and Reagents

Dendritic cells were cultured under conditions composed of HEPES-buffered RPMI-1640 medium, supplemented with 2 mM L-Glutamine, 100 micro (μ)g/ml streptomycin, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, 10mM non-essential amino acids, 10 mM essential amino acids, 50 mg/mlgentamicin, and 5×10−5 M β-2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich St Louis, MO). HCV core was purchased from Austral Biologicals(San Ramon, CA). Ovalbumin protein and the Lactate Dehydrogenase kit were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Chariot (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) was used to deliver HCV core protein into DCs. Anti-mouse-FITC, anti-cd11c-PE, anti-CD4- Cy5.5, anti-CD25-CD25, anti-FITC-iso, anti-PE-iso, anti-PercyP Cy5.5-iso were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Monoclonal HCV core antibody (mAb) was prepared as described (27). rIL-2 was purchased from eBioscience(San Diego, CA). Neuronal thread protein (NTP) was produced and used as a control (28).

Animals and Diet Regimen

Six-week old female Balb/c mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratory. They were placed on a control or ethanol liquid diet regimen for 8 weeks (Bioserv-Liquid Diet; Bioserv, Frenchtown, NJ) prepared according to manufacturer's instructions as previously described (18). During the first week, mice received 1.25 % ethanol (wt/vol) in their diet, which was gradually increased to 2.5% in the second week, and to 3.75% in the third week, and maintained at this concentration for the duration of the feeding regimen. A separate group of six-week old femaleBalb/c mice that received DC-based immunization were maintained on a standard chow diet. The spleen was collected upon sacrifice for isolation of DCs in all experiments. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Lifespan Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of DCs

Twelve and seven days before sacrifice, mice receiving their respective liquid diets were hydrodynamically injected with 10 micro (μ) gof a Flt3L expressing plasmid in 2mlsaline via their tail vein to expand the splenic DCspopulation as previously described (29). Spleens were collected upon sacrifice and DCs separated magnetically using CD11c+microbeads (Myltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA).

Immunizations

DCs were isolated from chronic ethanol fed and isocaloric pair fed controlled mice following in vivo expansion, and subsequently transfected with HCV core protein for 2 hours via the Chariot system in culture media as described (25). The DCs were collected (1 × 106), resuspended in 200 micro (μ) lof Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS), and injected subcutaneously in the flank of mice receiving chow diet to generate T cell responses. Vaccination was performed 3 times at two weeks interval, and mice receiving immunization generated from control-fed mice were kept separate from ethanol-fed mice. As controls, a separate group of mice fed a chow dietary regimen were immunized in the same manner with either HCV soluble core or non-relevant neuronal thread protein(NTP) (2μg)proteins dissolved in HBSS.

HCV Core and Regulatory T cell Staining

Intracellular and cell surface staining was performed to detect HCV core transfection efficiency and the generation of Tregs respectively. After HCV core transfection using the Chariot system, 1 × 106 DCs were stained for CD11c+ using anti-cd11c-PE. Intracellular staining of HCV core was then performed with an anti-HCV core mAb and detected with anti-mouse-FITC using the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA). For Tregcell identification, 1 × 106 splenocytes isolated from the spleen of immunized mice were stained for CD4+ or CD25+ with anti-CD4-PercP Cy5.5 and anti-CD25-Alexa Fluor 488. Anti-FOXP3-PE was then used for intracellular identification of FOXP3 expression. Isotype staining was performed correspondingly as controls. All experiments were evaluated using FACS Calibur(BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and analyzed with Flowjo software.

Cytokine Measurement

Splenocytes isolated from core-loaded DC-immunized mice were incubated with 1 μg/ml of HCV core protein for 24 hours in culture media. Splenocytes were then collected, spun down, and the supernatant collected for quantification of IL-2, TNF-α and IL-4 cytokine secretion via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISAs were purchased from eBioscience(San Diego, CA) and the protocol was followed according to manufacturer's instructions

Cytotoxicity Assay

DCs isolated from control- and ethanol-fed mice, were transfected with HCV core protein, and co-incubated with splenocytes derived from mice that received the core loaded DC immunization at 1:100 ratio in a re-stimulation step, followed by incubation with rIL-2 for 3 days. The co-incubation was matched so that core loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice were incubated with the splenocytes from the mice immunized by the core loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice, for example. Likewise, for the negative controls, DCs derived from control-fed mice were used for the co-incubation step prior for the performance of the CTL assay. Splenocytes were then collected, counted and incubated with stable transfected HCV core-expressing SP2/19 cells (1×104) at 1:10, 1:50 and 1:100ratio (target cell:splenocyte) for 4 hours in a 96-well plate. After this procedure, cells were spun down, and the supernatants used to measure LDH release from SP2/19 cells (30).

Statistical Analysis

All results were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism program, where individual categories were compared using a non-paired Student t test. Statistically significant results were considered if the p<0.05.

Results

HCV coretransfection of DCs

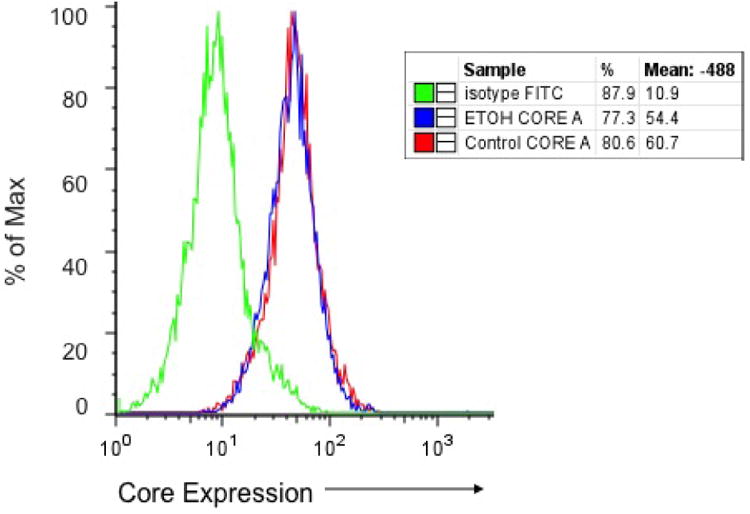

DCs were isolated from control and ethanol-fed mice, and cultured with HCV core protein for 4 hours using the HCV core-Chariot delivery system (25). Intracellular staining of HCV core was performed and analyzed by flow cytometry to determine if HCV core was being transfected efficiently into DCs for subsequent immunization. Both control and ethanol derived DCs were successfully transfected with and exhibited comparable levels of HCV coreexpression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. HCV core transfection into DCs.

The DCs were isolated from ethanol and pair fed control Balb/c mice using the anti-cd11c+ magnetic microbeads, and transfected with HCV core protein using the Chariot system for two hours. Intracellular staining, as analyzed by flow cytometry, revealed that DCs from both diet groups have similar transfection efficiencies with an average fluorescence emission of 58%.

Mice immunized with HCV core loaded DCs derived from ethanol fed mice exhibit reduced CTL activity

Previous studies performed by Kuzushita et al. demonstrated a specific CTL response in chow-fed mice immunized with HCV core when compared to mice that were immunized with DCs alone or with medium as controls (25). Similarly, Aloman et al. demonstrated a reduced CTL response to HCV NS5 after genetic immunization with a HCV NS5 expression plasmid to mice fed with ethanol for 8 weeks compared to animals consuming an isocaloric control diet (18). Therefore, we hypothesized that HCV core-loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice might also produce a reduced CTL immune response following immunization as compared to mice immunized with HCV core-transduced DCs derived from control liquid diet fed animals.

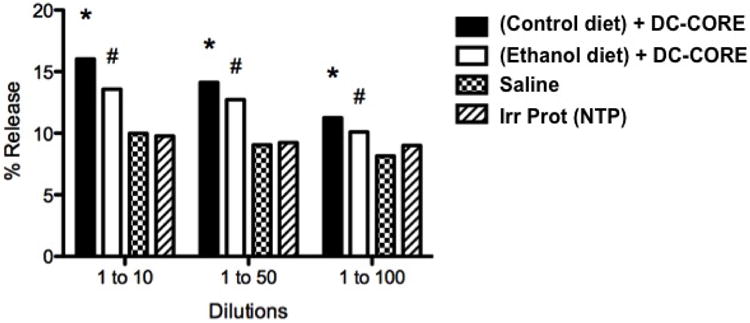

To evaluate this possibility, Balb/c mice were pair-fed control and ethanol containing liquid diet for 8 weeks. DCs were then isolated, transfected with HCV core protein using the Chariot system, and used for immunization of chow-fed mice. Mice that received the HCV core immunization delivered by DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice exhibited a significantly lower HCV core-specific CTL activity compared to mice that received the DC-core immunization prepared from isocaloric liquid diet fed control mice. (Figure 2) This observation was consistent at different SP2/19 target cell:splenocyteratios. Immunizing mice with core-loaded DCs prepared from either control or ethanol-fed mice demonstrated the efficacy and immunogenicity of this HCV viral structural protein as well as the vaccine delivery method, and subsequent generation of an antigen-specific immune response.

Figure 2. Immunization with DC-core from mice fed control diet exhibit higher in vitro cytotoxicity against HCV core-expressing SP2/19 cells compared to DCs derived from ethanol fed animals.

Balb/c mice were immunized (X3 at 2 week interval) with DC-core from control and ethanol pair-fed mice. Splenocytes were isolated from the immunized mice, and incubated with rIL-2 and HCV core transfected DCs from control and ethanol-fed mice, (restimulation step) at a 1 to 100 ratio (DC to splenocytes) for 3 days. Splenocytes from HBSS- and control-immunized mice were incubated with HCV core DCs derived from control-fed mice. Splenocytes were subsequently harvested and incubated with HCV core expressing SP2/19 cells (1×104 cells/well) at 1:10, 1:50 and 1:100 ratio (SP2/10 target cell:splenocyte) for 4 hours; Lactate Dehydrogenase release was measured as an index of CTL activity and was comprised of measurements on 8 wells for each experiment which was repeated three times. Significantly higher in vitro cytotoxicity was observed in mice fed the control diet and immunized with HCV core transfected DCs compared to mice immunized with DCs derived from ethanol fed mice (*P<0.05). Immunization with HCV core from either control-fed or ethanol-fed mice, however, exhibited higher cytotoxicity against SP2/19 cells compared to mice immunized with HBSS or irrelevant protein (#P<0.001). Experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

T cell activation is impaired when receiving core loaded DC immunization derived from ethanol-fed mice

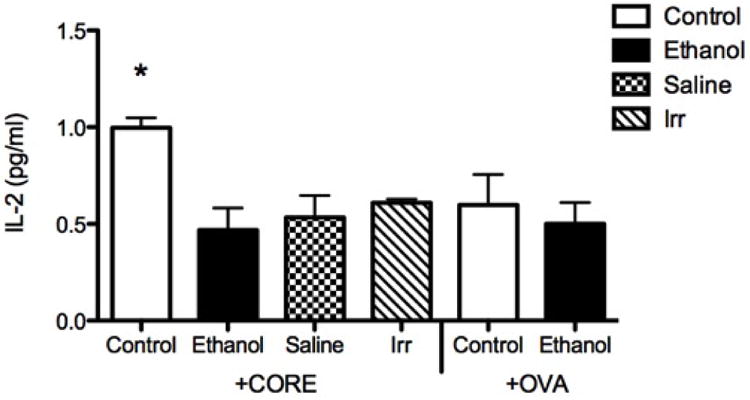

Previous studies have shown that chronic ethanol consumption is associated with reduced IL-2 expression and secretion in mice due to abnormalities in the DC antigen presentation pathway, thereby decreasing T cell activation(31). To determine whether CD4+ and CD8+T cells function was altered by chronic ethanol in mice receiving HCV-core loaded DCs, splenocytes from immunized mice were stimulated with 1 micro (μ) g/ml HCV-core in vitro for 24 hours, and supernatants harvested and analyzed for IL-2 levels. Immunizing mice with core loaded DCs from control-diet fed mice produced higher amounts of IL-2 levels compared to mice receiving core loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed animals, which had similar levels to mice immunized with saline or irrelevant NTP protein, indicating that ethanol impairspriming of T cells against this HCV structural protein(Figure 3). Moreover, T cell activation was antigen specific because incubating splenocytes derived from both ethanol and control derived DC-core-immunized mice with 1 micro (μ) g/ml OVA protein did not influence levels in culture supernatants.

Figure 3. Mice immunized with HCV core loaded DCs from ethanol-fed mice exhibit low IL-2 secretion.

Splenocytes from mice immunized with HBSS, irrelevant protein, and core loaded DCs derived from control and ethanol fed mice were isolated and incubated with 1micro g/ml soluble HCV core protein for 24 hours. Splenocytes were harvested and centrifuged; the supernatant was collected for measuring IL-2 via ELISA. IL-2 concentrations were higher in splenocyte culture derived from mice immunized with core loaded DCs from controls compared to splenocytes from mice immunized with core loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice, HBSS, or irrelevant protein (*P<0.001). Each assay was run in triplicate and the experiments were repeated three times. These observations suggest that immunizing mice with ethanol-derived, core-transfected DCs alters CD4+ T cell activation (18, 25) against HCV core.

Mice receiving HCVcore loaded DC immunization from ethanol fed mice exhibit reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels

TNF-α and IL-4 are cytokines have been associated with induction of a TH1 and TH2immune response, which activate macrophages and induce B and T cell proliferation(32, 33). Expression of both of these cytokines has been proposed to play a role in both ethanol-induced as well as HCV-induced liver injury(34, 35). We determined if the DC-based immunization approach would also produce inhibitory effects in mice immunized with core loaded DCs derived from ethanol or isocaloric pair fed (control) mice. The secretion of both of these cytokines was impaired in mice immunized with ethanol-derived and HCV core loaded DCs following stimulation of splenocytes in vitro with core protein; however, there was no difference in TGFβ and IL-10 secretion (data not shown)(Figure 4). In addition, there was no significant difference in secretion of both TNF-α and IL-4 between control and ethanol-derived core loaded DCs when stimulated in vitro with OVA, indicating that the antigen specific immune sensitization was provided by the HCV core-loaded DCs in vivo. These results suggest that chronic ethanol consumption inhibits the host's inflammatory response following core loaded DC immunization.

Figure 4. Immunizing mice with HCV core loaded DCs from ethanol-fed mice produces an altered cytokine response.

Splenocytes from mice immunized with core loaded DCs from control-fed and ethanol fed mice were incubated with soluble HCV core or OVA protein for 24 hours. The cell supernatant was collected and used for measuring TNF-α and IL-4 levels via ELISA. Mice who received immunizations with core loaded DCs from pair-fed control mice had higher levels of TNF-α and IL-4 compared to mice that received immunizations with core loaded DCs derived from ethanol fed mice (*P<0.05). Splenocytes pulsed with OVA for 24 hours confirmed the HCV core-specific response. Each assay was run in triplicate and the experiments were repeated three times.

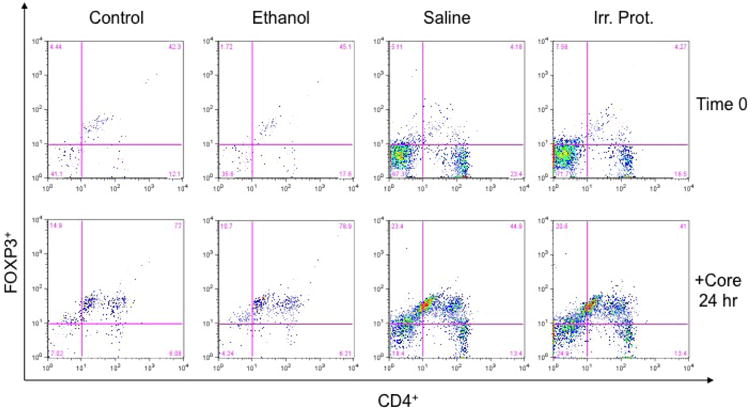

Increased levels of CD25+FOXP3+ and CD4+FOXP3+ T regulatory cells are observed following core loaded DC immunization derived from chronic ethanol fed mice

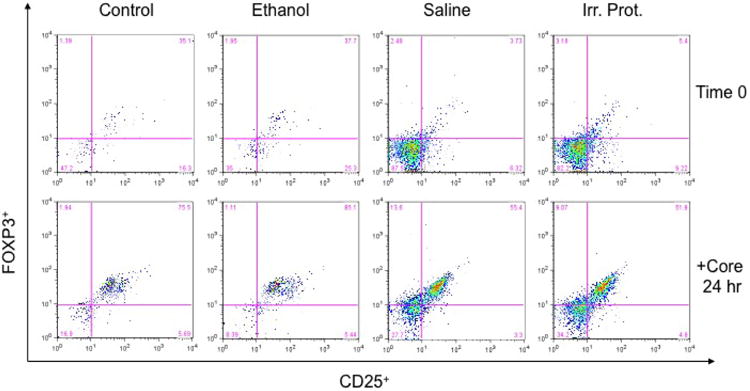

The reduced CD4+ and CD8+ activity in mice immunized with HCV core loaded DCs derived from ethanol fed mice may be due to induction of Tregs. To examine this possibility, the Treg levels were evaluated in the total splenocyte population isolated from mice immunized with core- loaded DCs derived from control and ethanol-fed mice as well as groups receiving saline and irrelevant NTPantigen. Analysis was performed following after a24 hour incubation restimulation with HCV core protein (1 μg/ml). Mice that received the core loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice exhibited an expanded population of both CD25+FOXP3+ (Figure 5) and CD4+FOXP3+ Tregs (Figure 6) by FACS analysis compared to mice receiving core loaded DC immunization derived from control-diet fed animals, or those injected with saline or irrelevant NTPprotein. This finding suggests a potential mechanism(s) for the observed reduced CD4+ and CD8+ immuneresponses following core loaded DC immunization and may suggest an additional effect produced by ethanol on DC function other than reduced cytokine secretion(18, 31).

Figure 5. CD25+FOXP3+ Tregsare increased in mice immunized with HCV core loaded DCs derived from ethanol-fed mice.

Splenocytes from immunized mice with core loaded DCs derived from control and ethanol-fed mice were isolated and stained for CD25+FOXP3+ expression before and 24 hours after incubation with 1 micro (μ) g/ml HCV core protein. Incubation with HCV core increased the levels of CD25+FOXP3+ Treg cells in core-DC-immunized mice from both ethanol and control diet pair fed groups. However, core-DC-immunized mice, derived from chronic ethanol fed mice, had a higher CD25+FOXP3+ population than mice immunized with HCV core loaded DCs derived from controls; both of which were found to be higher than in mice immunized with saline or irrelevant protein (NTP). Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. At 24 hours, the values were control 75.5, ethanol 85.5, saline 55.4 and irr protein 51.9.

Figure 6. CD4+FOXP3+ T cells are increased in mice immunized with HCV core loaded DCs derived from chronic ethanol fed mice.

Splenocytes from immunized mice with HCV core loaded DCs derived from control and ethanol-fed mice were isolated and stained for CD4+FOXP3+ expression before (time 0) and 24 hours after incubation with HCV protein (1μg/ml). Incubation with HCV core increased CD4+FOXP3+ expressing cells in core loaded DC immunized mice derived from both diet groups. However, HCV core loaded DC immunized mice, obtained from chronic ethanol fed mice had a higher CD4+FOXP3+ expressing population than either core-DC-immunized mice derived from controls or mice immunized with saline or irrelevant protein. Experiments were repeated three times with similar results. At 24 hours, the values were control 73, ethanol 81.5, saline 44.9 and irr protein 43.0.

Discussion

The mechanism(s) of HCV-mediated liver injury and potential synergistic adverse effects in combination with ethanolabuse on the host immune response have not been well elucidated. Previous studies have proposed a role of HCV core protein in combination with chronic ethanol consumption to produceoxidative stress, lipid oxidation, increased apoptosis, altered regulation of the MAPK signaling pathway(36), and subsequent inhibition of anti-viral host immune response(36, 37)(37, 38). The latter is of particular interest because alcoholics'appear to be predisposed to persistent viral infection, a finding believed to be linked to a blunted host immune response initiated by DCs through reduced viral peptide presentation(31). This action by ethanol is amplified during HCV infection since it interferes with DC mediated TH1 (12) and TH17 activation by upregulating anti-inflammatory molecules such as TGF-β and IL-10 (39), while reducing IFN-α levels (34, 40). Therefore, understanding the possible mechanisms of ethanol effects on host immune responses to HCV core could help define immunologic factors important in viral clearance from the liver.

Past investigations have revealed potent inhibitory effects of ethanol on viral-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses against HCV nonstructural proteins that were capable of being partially reversed by ethanol abstinence (41) as well as by genetic immunizations through amplifiedsecretion of GM-CSF and IL-2, at the site of vaccination; such cytokines may improve activation of APCs(23) to induce viral specific immune responses. Further studies have confirmed the importance of DCs inpromoting anti-viral immune responses by utilizing them as vehicles for delivering viral structural and non-structural proteins to activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. This DC based vaccine approach takes advantage of their phagocytic and antigen presenting properties to sensitize host CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against HCV structural and non-structural proteins. Indeed, such methods have been shown to increase viral-specific CTL response against HCV NS5 and core proteins(25, 26, 42). In this context, Aloman et al. demonstrated that the transfer of DCs from ethanol-fed mice immunized with an NS5-expressing plasmid to other ethanol-fed mice did not improve the NS5-specific response whereas immunizedmice receiving the DCs derived from control-fed mice did. Such findings illustrate ethanol's inhibitory effects on DC function and the subsequent ability to generate appropriate anti-viral activity to HCV core protein; however, the mechanisms involved in this altered immune response are largely unknown.

In this study, we suggest apotential role for Tregs in ethanol-fed mice that may contribute to depressed cellular immune responses to HCV core protein. Utilizing the DC-based immunization approach, we evaluated the immune response in chow-fed mice to HCV core protein after being immunized with DCs loaded with HCV core that were derived from either control or ethanol fed mice. Ethanol-derived core loaded DCs produced lower IL-2 levels after in vitro stimulation compared to core loaded DCs derived from control diet fed animals. In addition, there was impaired release of IL-4 and TNF-α. Furthermore, ethanol derived DC-core induced significantly less CTL activity at various lymphocyte target cell ratios. These experiments evaluated the evolution of host immune response by using the entire splenocyte T cell populations for all in vitro stimulation experiments, as well as employing HCV core loaded DC immunizations when activating a CTL response in the presence or absence of prior chronic ethanol consumption. These results were HCV-core specific since in vitro stimulation with non-relevant NTP did not elicit a CTL response or IL-2 release. Similarly, in vitro stimulation with OVA albumin did not induce IL-2 and TNF-α release in either control or ethanol derived HCV core loaded DCs immunized groups confirming antigenicspecificity.

These observations suggest that DCs isolated from ethanol-fed mice are unable to fully support generation of T cell responses compared to core loaded DCs immunization derived from isocaloric pair fed control animals. The possible mechanism(s) of this effect was further explored. Regulatory T cells include natural Tregs developed in the thymus, or adaptive Tregs which develop in the periphery as a result of IL-2 trapping, cytokine production such as IL-10 and TGF-β, and cell-cell based interactions. Their activation attenuates effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activity by direct targeting or by inhibiting APCs, inducing cell cycle arrest, altering pro-inflammatory cytokine release or inducing apoptosis (43). Because of their role in suppressinganti-viral immune response(s), we hypothesized that Tregs may be involved in the poor CD4+ and CD8+ sensitization to HCV coreprotein in the ethanol derived core loaded DC immunized group. Mice vaccinated with core loaded DCs from ethanol fed mice exhibited a higher CD25+FOXP3+ and CD4+FOXP3 Treg population compared to mice immunized with DC-core derived from isocaloric pair fed controls. These results suggest a potential interaction between chronicethanol consumption and T-reg generation, thereby suppressing DC-mediated T-cell sensitization against HCV core protein; further studies will be required to determine if it is due to a direct interaction of Tregs with HCV core sensitive CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells or to redcued cytokine secretion and altered antigen presentation by DCs as previously described (18, 31, 35) It is also important to note that the levels of CD4+ T cells (Figure 6) are higher in mice immunized with core loaded DCs derived from control than with core loaded DCs obtained from chronic ethanol fed mice. Indeed, there is a higher number of effector CD4+ T cells and reduced levels of CD4+FOXP3+ T cells when comparing mice immunized with core loaded DCs derived from control compared to ethanol that may explain, in part, the reduced in vitro and in vivo generation of CD4+ and CD8+ anti-viral immune responses.

We hypothesize that immunosuppression may be mediated by a direct DC-Treg interaction, whereby Inducible Costimulatory Molecule (ICOS) on the Treg surface may interact with Inducible Costimulatory Molecule Ligand (ICOS-L) on DCs. Previous studies have shown that ICOS-L on DCs is upregulatedas a consequence of chronic ethanol consumption and this phenomenon may contribute to their inability to trigger an effective T cell response (31). Moreover, other investigations have demonstrated that ICOS expression isassociated with CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ T cell accumulation in the peripheryas well(44, 45).

Taken together, these studies demonstrate that the poor sensitization against HCV core protein induced by ethanol-impaired DCs compared to that from control-fed mice resides mainly in their inability to activate CD4+ T cells, trigger a CTL response and induce TNF-α and IL-4 cytokine release. This immunosuppression may be due, in part, to an upregulation of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Treg population in the context of dysfunctional DCs with alteredcostimulatory ICOS molecule expression. These observations suggestpotential new mechanisms to consider with respect to ethanol immunosuppressive effects on the host CD4+ and CD8+ anti-viral immune response, and establish aputative role for interactions between ethanol altered DCs and the generation of Tregs that may contribute to persistent HCV infection in alcoholics.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by: N.I.H. Grant(s) RO1 AA08196 and NTH AA0819Administrative Supplement

Jack R. Wands outlined the studies, provided the research support and was involved in manuscript preparation.

Vivian Ortiz designed and performed the experiments, participated in data analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen presenting cells

- CD8+

cytotoxic cells

- CTL

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

- DCs

dendritic cells

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- GM-CSF

granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HBSS

Hank's balanced salt solution

- Th1

helper T cell

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- LD

lactate dehydrogenase

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- mAb

monoclonal antibodies

- NTP

neuronal thread protein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Tregs

T regulatory cells

- CD4+

viral specific helper cells

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report

References

- 1.Bartenschlager R, Cosset FL, Lohmann V. Hepatitis C virus replication cycle. J Hepatol. 2010 Sep;53(3):583–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.015. Epub 2010/06/29. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Averhoff FM, Glass N, Holtzman D. Global burden of hepatitis C: considerations for healthcare providers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Jul;55(1):S10–5. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis361. Epub 2012/06/22. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989 Apr 21;244(4902):359–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. Epub 1989/04/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001 Sep 22;358(9286):958–65. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. Epub 2001/10/05. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ascione A, De Luca M, Tartaglione MT, Lampasi F, Di Costanzo GG, Lanza AG, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin is more effective than peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for treating chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jan;138(1):116–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.005. Epub 2009/10/27. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Jun 23;364(25):2417–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Mar 31;364(13):1195–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asselah T, Benhamou Y, Marcellin P. Protease and polymerase inhibitors for the treatment of hepatitis C. Liver Int. 2009 Jan;29(1):57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01928.x. Epub 2009/02/12. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006 Oct;45(4):529–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.013. Epub 2006/08/02. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DM, McLauchlan J. Hepatitis C virus: assembly and release of virus particles. J Biol Chem. 2010 Jul 23;285(30):22733–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.133017. Epub 2010/05/12. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szabo G, Dolganiuc A. Hepatitis C core protein - the “core” of immune deception? J Hepatol. 2008 Jan;48(1):8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.005. Epub 2007/11/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmermann M, Flechsig C, La Monica N, Tripodi M, Adler G, Dikopoulos N. Hepatitis C virus core protein impairs in vitro priming of specific T cell responses by dendritic cells and hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2008 Jan;48(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.08.008. Epub 2007/11/14. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang T, Weinman SA. Causes and consequences of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation in hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Oct;21(3):S34–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04591.x. Epub 2006/09/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Bona D, Cippitelli M, Fionda C, Camma C, Licata A, Santoni A, et al. Oxidative stress inhibits IFN-alpha-induced antiviral gene expression by blocking the JAK-STAT pathway. J Hepatol. 2006 Aug;45(2):271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.01.037. Epub 2006/04/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, Goldberg DJ. Influence of alcohol on the progression of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005 Nov;3(11):1150–9. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00407-6. Epub 2005/11/08. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiff ER, Ozden N. Hepatitis C and alcohol. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(3):232–9. Epub 2004/11/13. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siu L, Foont J, Wands JR. Hepatitis C virus and alcohol. Semin Liver Dis. 2009 May;29(2):188–99. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214374. Epub 2009/04/24. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aloman C, Gehring S, Wintermeyer P, Kuzushita N, Wands JR. Chronic ethanol consumption impairs cellular immune responses against HCV NS5 protein due to dendritic cell dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 2007 Feb;132(2):698–708. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.016. Epub 2007/01/30. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osna NA, White RL, Krutik VM, Wang T, Weinman SA, Donohue TM., Jr Proteasome activation by hepatitis C core protein is reversed by ethanol-induced oxidative stress. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jun;134(7):2144–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.063. Epub 2008/06/14. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otani K, Korenaga M, Beard MR, Li K, Qian T, Showalter LA, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein, cytochrome P450 2E1, and alcohol produce combined mitochondrial injury and cytotoxicity in hepatoma cells. Gastroenterology. 2005 Jan;128(1):96–107. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.045. Epub 2005/01/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pianko S, Patella S, Sievert W. Alcohol consumption induces hepatocyte apoptosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000 Jul;15(7):798–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02083.x. Epub 2000/08/11. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castellano-Higuera A, Gonzalez-Reimers E, Aleman-Valls MR, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Santolaria-Fernandez F, De La Vega-Prieto MJ, et al. Cytokines and lipid peroxidation in alcoholics with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008 Mar-Apr;43(2):137–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm171. Epub 2008/01/25. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geissler M, Gesien A, Wands JR. Inhibitory effects of chronic ethanol consumption on cellular immune responses to hepatitis C virus core protein are reversed by genetic immunizations augmented with cytokine-expressing plasmids. J Immunol. 1997 Nov 15;159(10):5107–13. Epub 1997/11/20. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. Epub 1991/01/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzushita N, Gregory SH, Monti NA, Carlson R, Gehring S, Wands JR. Vaccination with protein-transduced dendritic cells elicits a sustained response to hepatitis C viral antigens. Gastroenterology. 2006 Feb;130(2):453–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.048. Epub 2006/02/14. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wintermeyer P, Gehring S, Eken A, Wands JR. Generation of cellular immune responses to HCV NS5 protein through in vivo activation of dendritic cells. J Viral Hepat. 2010 Oct;17(10):705–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01228.x. Epub 2009/12/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moradpour D, Englert C, Wakita T, Wands JR. Characterization of cell lines allowing tightly regulated expression of hepatitis C virus core protein. Virology. 1996 Aug 1;222(1):51–63. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0397. Epub 1996/08/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monte SM, Ghanbari K, Frey WH, Beheshti I, Averback P, Hauser SL, et al. Characterization of the AD7C-NTP cDNA expression in Alzheimer's disease and measurement of a 41-kD protein in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Invest. 1997 Dec 15;100(12):3093–104. doi: 10.1172/JCI119864. Epub 1998/01/31. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu F, Song Y, Liu D. Hydrodynamics-based transfection in animals by systemic administration of plasmid DNA. Gene Ther. 1999 Jul;6(7):1258–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300947. Epub 1999/08/24. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimoda M, Tomimaru Y, Charpentier KP, Safran H, Carlson RI, Wands J. Tumor progression-related transmembrane protein aspartate-beta-hydroxylase is a target for immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012 Jan 13; doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.016. Epub 2012/01/17. Eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eken A, Ortiz V, Wands JR. Ethanol inhibits antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011 Jul;18(7):1157–66. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05029-11. Epub 2011/05/13. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernandez-Pando R, Rook GA. The role of TNF-alpha in T-cell-mediated inflammation depends on the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance. Immunology. 1994 Aug;82(4):591–5. Epub 1994/08/01. eng. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romagnani S. Biology of human TH1 and TH2 cells. J Clin Immunol. 1995 May;15(3):121–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01543103. Epub 1995/05/01. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan EJ, Stevenson NJ, Hegarty JE, O'Farrelly C. Chronic hepatitis C infection blocks the ability of dendritic cells to secrete IFN-alpha and stimulate T-cell proliferation. J Viral Hepat. 2011 Dec;18(12):840–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01384.x. Epub 2011/11/19. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feng D, Eken A, Ortiz V, Wands JR. Chronic alcohol-induced liver disease inhibits dendritic cell function. Liver Int. 2011 Aug;31(7):950–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02514.x. Epub 2011/07/08. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsutsumi T, Suzuki T, Moriya K, Shintani Y, Fujie H, Miyoshi H, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein activates ERK and p38 MAPK in cooperation with ethanol in transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2003 Oct;38(4):820–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50399. Epub 2003/09/27. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hochrein H, Shortman K, Vremec D, Scott B, Hertzog P, O'Keeffe M. Differential production of IL-12, IFN-alpha, and IFN-gamma by mouse dendritic cell subsets. J Immunol. 2001 May 1;166(9):5448–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5448. Epub 2001/04/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisen-Vandervelde AL, Yao ZQ, Hahn YS. The molecular basis of HCV-mediated immune dysregulation. Clin Immunol. 2004 Apr;111(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.12.003. Epub 2004/04/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowan AG, Fletcher JM, Ryan EJ, Moran B, Hegarty JE, O'Farrelly C, et al. Hepatitis C virus-specific Th17 cells are suppressed by virus-induced TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2008 Oct 1;181(7):4485–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4485. Epub 2008/09/20. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dolganiuc A, Chang S, Kodys K, Mandrekar P, Bakis G, Cormier M, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein-induced, monocyte-mediated mechanisms of reduced IFN-alpha and plasmacytoid dendritic cell loss in chronic HCV infection. J Immunol. 2006 Nov 15;177(10):6758–68. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6758. Epub 2006/11/04. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Encke J, Wands JR. Ethanol inhibition: the humoral and cellular immune response to hepatitis C virus NS5 protein after genetic immunization. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000 Jul;24(7):1063–9. Epub 2000/08/03. eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gehring S, Gregory SH, Wintermeyer P, Aloman C, Wands JR. Generation of immune responses against hepatitis C virus by dendritic cells containing NS5 protein-coated microparticles. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009 Feb;16(2):163–71. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00287-08. Epub 2008/12/19. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009 May;30(5):636–45. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. Epub 2009/05/26. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busse M, Krech M, Meyer-Bahlburg A, Hennig C, Hansen G. ICOS mediates the generation and function of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells conveying respiratory tolerance. J Immunol. 2012 Aug 15;189(4):1975–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103581. Epub 2012/07/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi N, Matsumoto K, Saito H, Nanki T, Miyasaka N, Kobata T, et al. Impaired CD4 and CD8 effector function and decreased memory T cell populations in ICOS-deficient patients. J Immunol. 2009 May 1;182(9):5515–27. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803256. Epub 2009/04/22. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]