Abstract

Objective

Psychological well-being (PWB) has a significant relationship with physical and mental health. As part of the NIH Toolbox for the Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function, we developed self-report item banks and short forms to assess PWB.

Study Design and Setting

Expert feedback and literature review informed the selection of PWB concepts and the development of item pools for Positive Affect, Life Satisfaction, and Meaning and Purpose. Items were tested with a community-dwelling U.S. internet panel sample of adults aged 18 and above (N=552). Classical and item response theory (IRT) approaches were used to evaluate unidimensionality, fit of items to the overall measure, and calibrations of those items, including differential item function (DIF).

Results

IRT-calibrated item banks were produced for Positive Affect (34 items), Life Satisfaction (16 items), and Meaning and Purpose (18 items). Their psychometric properties were supported based on results of factor analysis, fit statistics, and DIF evaluation. All banks measured the concepts precisely (reliability ≥0.90) for more than 98% of participants.

Conclusion

These adult scales and item banks for PWB provide the flexibility, efficiency, and precision necessary to promote future epidemiological, observational, and intervention research on the relationship of PWB with physical and mental health.

Keywords: psychological assessment, well-being, positive affect, life satisfaction, meaning

Introduction

Research on psychological well-being (PWB) has received increasing attention over the past decade in part due to the growth of the positive psychology movement [1] and renewed interest on the relationship between positive psychology and health [2]. Research examining the relationship between PWB and health has primarily been focused on positive affect and health and has revealed links with physical, psychological, and social health. For physical health, PWB has been associated with increased longevity [3; 4], perceptions of good health in older adults [5], and decreased loss of functional status and mobility [6]. In a meta-analytic review, PWB was associated with reduced mortality in healthy population-based studies [7]. Links to better psychological health have been found between PWB and positive coping with life circumstances [8] and between PWB and resilience, endurance, and optimism [9]. PWB has also been associated with more and closer social contacts as evidenced by links between PWB and more diverse and closer social ties [10].

Consistent with theoretical conceptualizations of PWB, previous approaches to measuring PWB have emphasized both an experiential and an evaluative component [11]. The experiential component, known as hedonic well-being, includes positive emotions whereas the evaluative component, known as eudaimonic well-being, includes cognitive evaluations of life purpose and meaning [12; 13]. For the NIH Toolbox, we concentrated on both affective experiences (positive affect) and cognitive evaluations (life satisfaction, meaning and purpose) that are critical components of “living well” [14] and thus key aspects of emotional health throughout life. Positive affect has been characterized as happiness, contentment, positive energy, and interest in pleasurable or achievement-relevant activities [15]. Pressman and Cohen [16] defined positive affect as “feelings that reflect a level of pleasurable engagement with the environment such as happiness, joy, excitement, enthusiasm, and contentment.” Positive affect bears a strong relationship to overall feelings of life satisfaction but is conceptually distinct [17].

Life satisfaction is the cognitive evaluation of life experiences rather than reports of a pure affective state. Items assessing this concept are usually phrased in a general or global way, rather than having a momentary or recent recall period. Unlike measures of pure affect, life satisfaction measures are strongly influenced by expectations. Thus, individuals can report a high level of satisfaction if they genuinely experience their lives as going well, or if their expectations are low, regardless of how well their lives are going. For this and other reasons, it is helpful to assess both affect and satisfaction.

Assessments of meaning and purpose are cognitive evaluations of the extent to which people feel their life reflects goals and purposes beyond their current affect and satisfaction. These assessments contain elements of doing things viewed as “good” and being a person engaged in positive activities (cf. [14]). There is conceptual overlap with life satisfaction with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.41 [18] to as high as 0.71 [19]. However, life satisfaction focuses on whether or not people like their lives, and meaning is more specifically concerned with the extent to which people feel their life matters or makes sense [20].

The NIH Toolbox for Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function (www.nihtoolbox.org) is a project to identify, create and validate brief comprehensive assessment tools to measure outcomes in longitudinal, epidemiological and intervention studies across the lifespan in the areas of cognition, emotion, motor and sensory function. The project is one of the initiatives in the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research [21]. The NIH Toolbox objectives are to provide a standard set of measures across diverse study designs and populations and maximize yield from large, expensive studies with minimal increment in subject burden and cost. In order to accomplish these goals, core batteries for cognition, emotion, motor, and sensory function were developed and will be normed for ages 3–85 years old.

Within the emotion domain, the mandate for the NIH Toolbox was to develop assessments with a broad focus, incorporating healthy emotional functioning. This process was guided by a review of the literature, an NIH Toolbox Request for Information from experts in the area of emotional health, follow-up semi-structured interviews with a subset of these experts, and discussion within the emotion domain team and among the emotional health expert consultants [22]. We identified four sub-domains of particular relevance to health outcomes – Negative Affect, PWB, Stress and Self-Efficacy, and Social Relationships. An overview of this process is discussed elsewhere [23].

This report focuses on the development of self-report measures for the PWB subdomain of the NIH Toolbox for adults aged 18 years old and above. Our data collection and analytic approach relied heavily on item response theory (IRT), a modern approach to test construction and evaluation [24]. The development of item banks (i.e., a set of carefully calibrated questions that develop, define and quantify a construct) can inform the creation of robust short forms and the application of computerized adaptive testing (CAT). By enhancing measurement efficiency, precision, and flexibility, IRT applications are particularly useful analytic strategies for the goals of the NIH Toolbox in general, and measurement of PWB specifically.

Methods

Item Pool Development

We performed extensive literature searches and received recommendations for measures assessing positive affect, life satisfaction, and meaning from 20 Ph.D. consultants and experts in measurement science who were nominated and approved by the NIH Toolbox Steering Committee to serve as contract-funded consultants and co-investigators. We drew content ideas and coverage from existing, well-validated measures of PWB. This iterative process helped to generate and refine items that covered the breadth of content included in the concepts of PWB (cf. [25; 26]). Comprehensive literature searches adapted the general strategies described by Klem et al. [27] and were performed using the PubMed, PsycINFO, Buros Institute Test Reviews Online, Educational Testing Service, Patient-Reported Quality of Life Instrument Database, Tests and Measures in the Social Sciences, and Health and Psychosocial Instruments databases. Cited reference searches were completed for the primary reference for each measure in order to determine its acceptance and use by the scientific community. For the Toolbox emotion domain, 554 measures were identified; 77 of them assessed concepts associated with PWB. In addition, a careful review of intellectual property issues was done for all measures. Items from proprietary measures (n=5 adult measures) were excluded. We supplemented existing measures with items from other measures to maximize the breadth of content coverage. We standardized item context (recall periods), item stems (verb tense), and response options to minimize respondent burden. Table 1 shows the number of items included for PWB and the source instrument. Item selection results for each of the PWB concepts are described below and items and response options comprising each of the three calibrated banks are listed in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Item Pools, Source Instrument, and Calibrated Banks for Adults by Concept

| Psychological Well-Being Concept |

Initial Item Pool |

Calibrated Item Bank |

Item Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | 44 | 34 | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form (PANAS-X), Affectometer-2, Mental Health Inventory, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp), Brief Mood Introspection Scale, Benefit Finding Scale |

| Life Satisfaction | 50a | 16 | Satisfaction with Life Scale, Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale, Domain-Specific Life Satisfaction Items from the CDC |

| Meaning & Purpose | 18 | Life Engagement Test, Meaning in Life Questionnaire, European Social Survey, FACIT-Sp, Benefit Finding Scale, Mental Health Inventory |

The item pool for Life Satisfaction and Meaning & Purpose was initially combined and concepts were separated after reviewing factor analysis results.

Participants

Adult subjects (ages 18 or older) were drawn from the United States general population, by Toluna (http://www.toluna-group.com), an internet panel company. Internet panels are increasingly used as a viable means of data collection due to the widespread availability of the internet among diverse groups and the low cost and efficient means of data collection provided by the internet [28]. Moreover, Liu et al. [29] have shown the representativeness of internet data is comparable to data from probability-based general population samples. To recruit study participants, Toluna sent emails to invite potential participants from their databases to enroll in the current study following a screening process to ensure eligibility (based on age, current English-speaking). Following initial screening, 3,648 respondents completed a demographic survey and were assigned to one of three study arms. Of those participants, 2,551 provided complete data. Participants who completed the PWB items (n=1,111) were administered identical questionnaires and eligible for incentive-based compensation through Toluna. Procedures for data quality control are described at http://us.toluna-group.com/toluna-difference/quality/. After removing suspicious cases for “straightlining” (i.e., same response within blocks of 15 or more items), data from 522 adults (mean age=44.9; 61% female) were examined. Detailed demographic information is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participant Information

| Adult (n=552) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | Mean=44.9 SD=16.2 Range=18–90 |

|

| Gender | Male | 39.1% |

| Female | 60.9% | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 6.2% |

| Non-Hispanic | 93.8% | |

| Race | White | 86.1% |

| African-American | 9.6% | |

| Asian | 3.1% | |

| General Health | Excellent | 10.3% |

| Very Good | 34.4% | |

| Good | 33.5% | |

| Fair | 17.8% | |

| Poor | 4.0% | |

| Household Income | < $20,000 | 18.8% |

| $20,000-$39,000 | 27.5% | |

| $40,000-$74,999 | 30.6% | |

| $75,000-$99,000 | 8.0% | |

| $100,000 or more | 9.2% | |

| Highest grade completed | Less than high school | 4.9% |

| High school graduate | 16.3% | |

| Some college | 45.8% | |

| College graduate | 24.3% | |

| Advanced degree | 8.7% | |

| Employment Status | Full-Time Employed | 31.5% |

| Retired | 17.6% | |

| Unemployed | 14.5% | |

| Part-Time Employed | 11.8% | |

| Homemaker | 11.8% | |

| On Leave of Absence, including disability | 7.6% | |

| Full-Time Student | 5.3% | |

| Marital Status | Married | 43.8% |

| Never Married | 25.4% | |

| Divorced | 14.9% | |

| Living with partner | 10.0% | |

| Widowed | 4.2% | |

| Separated | 1.8% | |

Data Analysis

Analyses followed general guidelines used in the PROMIS item bank development [25; 26] and were grouped into two phases: (1) Testing assumptions for IRT modeling -unidimensionality and local independence of items; and (2) Estimating item parameters using IRT and creating fixed-length forms for norming. Item inclusion/exclusion was decided by group consensus after reviewing analysis results and item content.

As part of phase 1, we examined items for sparse data within any rating scale category (i.e., N<5). We also identified violations of monotonicity (average scores of people across the range of item response categories should increase monotonically) for their potential impact on subsequent IRT analyses. Corrected item-total correlations were used to identify non-contributing items within each domain. Data were randomly divided into two datasets, one for exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the other for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), using the SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Gary: North Carolina) and MPlus 6.1 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles: CA), respectively. EFA with PROMAX rotation was used to identify potential factors among items and CFA was used to confirm final factor structure. Because the data were ordinal in nature, we used polychoric correlations in the factor analyses. In the EFAs, eigenvalues >1.0 and scree plots were used as criteria to estimate meaningful factors. To enhance the unidimensional nature of factors, items with factor loadings < 0.4 were considered for exclusion. In the CFAs we used weighted least squares and fit statistics to evaluate dimensionality of the item pool. Fit indices are influenced by multiple factors such as sample size, distribution and numbers of items [30], and we selected the commonly used indices for item banking as adopted by the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Residual correlations were used to evaluate local dependency between item pairs to avoid potential secondary factors from locally dependent items.[31]

In phase 2, items that met unidimensionality assumptions were analyzed using Samejima’s Graded Response model (GRM)[32] as implemented in Multilog IRT software.[33] The GRM is one of the most commonly used IRT models in health-related quality of life research and yields difficulty and discrimination parameters. The difficulty parameter (i.e., threshold) of an item is reflected by the probability of a participant endorsing a particular response for an item depending upon his/her level of the construct relative to the location of that item on the construct continuum. The discrimination parameter (i.e., slope) describes how well an item discriminates among individuals at different points along the continuum. The IRT-based information function was used to estimate reliability and error functions at both scale and item levels, to allow examination of precision levels along the measurement continuum. The information function presents the degree of measurement precision, which varies along the continuum and can be converted into a reliability function (criterion: reliability > 0.7). In IRT models, reliability varies at different levels, as can the consequences of various precision levels. Items displaying poor IRT fit (criterion: significant S-X2 fit statistic, p<0.01 [34]) and poorly discriminating items (i.e., those with unacceptable IRT slopes; criterion: slope < 1) were candidates for exclusion at this stage. Final inclusion/exclusion decisions were determined by the research team after review of individual item properties and content vis-à-vis the entire item bank.

In this study, we conducted differential item functioning (DIF) analyses on the basis of age (“< 50 years” versus “ ≥ 50 years”), education (“<1 year in college” versus “>1 year”) and gender for groups with a minimum of 150–200 participants per subgroup.[35] An item has significant DIF if the item exhibited different measurement properties between subgroups, which is similar to “item bias” a common term used in educational settings. DIF exists when characteristics such as age, gender, or education, which may seem extraneous to the assessment of domains of interest, have an effect on measurement. Specifically, we tested for DIF using an ordinal logistic regression procedure [36] with criteria: p< 0.01 and R2 > 0.02. [37] Items that demonstrated DIF on more than one comparison were removed. Lastly, fixed-length forms, an intermediate measure between short forms and full item-banks, were determined in a consensus meeting where the research team (comprised of psychometricians, NIH representatives, content-expert consultants, and measurement scientists) reviewed item content across age groups, CAT simulations, and other psychometric properties. Due to constraints of responder burden, we limited PWB to 45 items across all concepts for norming testing. Fixed-length forms allowed us to obtain data on a maximum number of items from each of the three item banks in the norming data than if we administered short forms or CATs alone.

Results

Positive Affect

Testing assumptions for IRT

Item-total correlations among 44 items being tested ranged from 0.47 (I felt interested in other people) to 0.81 (I felt happy). In the initial EFA, five factors had eigenvalues >1.0 (values = 22.1, 2.6, 1.9, 1.8 and 1.3 for the first five factors, respectively) and only one factor before the elbow in the scree plot, which explained 79% of total variance. Inter-factor correlations of these five factors ranged from 0.36 (factors 3 & 4) to 0.57 (factors 1 & 2). After reviewing item content, the research team conducted a second run of EFA excluding items having factor loadings < 0.3 on all of the first three factors – happiness, serenity, cognitive engagement. Results from the second EFA identified one dominant factor among these 38 items: one factor before the elbow in the scree plot, all items had factor loadings > 0.4 and this factor explained 20.04% of variance. Acceptable fit indices (CFI=0.93, TLI=0.985, RMSEA=0.11) were found from CFA after four more items were removed due to local dependency (residual correlations > 0.15) and content evaluation. Thus, the proposed positive affect bank is free of locally dependent items and is essentially unidimensional for purposes of scaling with IRT models.[38; 39]

Estimating item parameters

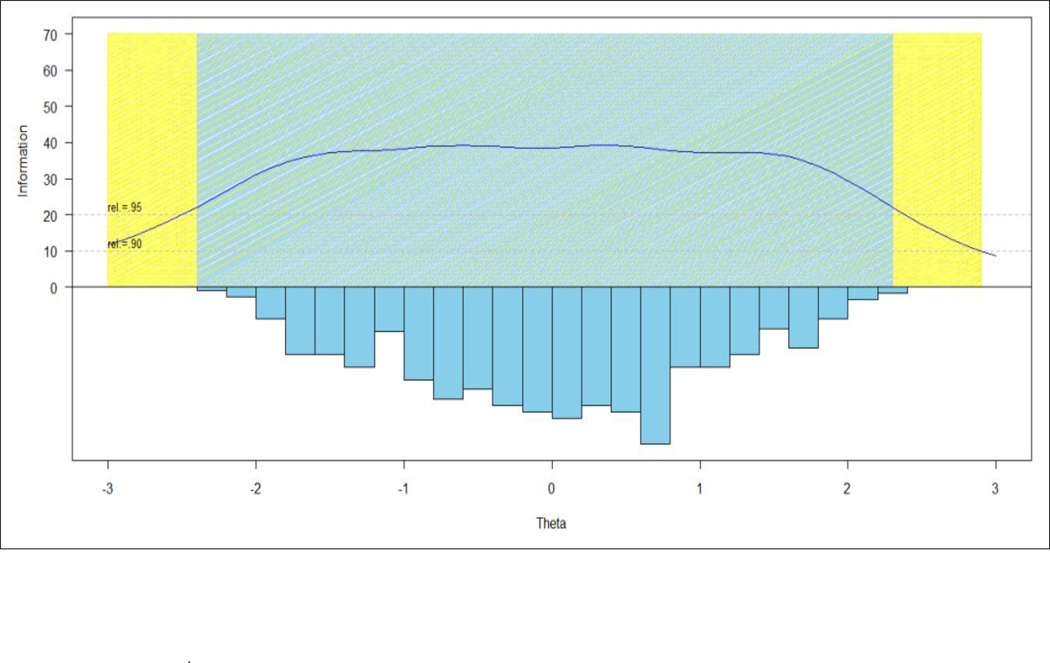

In IRT analysis, all 34 items had acceptable fit values (S-X2, p>0.01). Slope (discrimination) parameters of these items ranged from 1.0 (I was thinking creatively) to 3.3 (I felt happy) and threshold (difficulty) ranged from −3.6 (I felt determined) to 2.7 (I felt fearless). Scale information function was estimated based on these parameters. Figure 1 shows the precision of these 34 items in measuring this sample, with reliabilities all >0.95. These items measured positive affect with high precision across the continuum of the positive affect construct.

Figure 1.

Precision Levels across the Positive Affect Measurement Continuum

Note: In these figures, the Y-axis represents information function which was then converted to reliability function; X-axis is the IRT-scaled score (theta) where reliability of each score was estimated. The area plotted in blue is mean scores with a reliability ≥ 0.95. The area plotted in yellow represents mean scores with a reliability between 0.9(inclusive) and 0.95 (exclusive). The bottom half of the figure is the participants’ positive affect scores represented in histogram and the upper part of the figure is the information function curve of items, with the cut-off lines for a reliability of 0.95 and 0.90 plotted, respectively.

Analyzing DIF

Four items had significant DIF (p<.001; “I felt excited”, “I felt at ease”, “I felt able to concentrate”, and “I felt a sense of harmony within myself”) between age groups with one item at a meaningful magnitude (“I felt excited”, R2 =0.0231); one item showed statistically significant (p<.01) gender DIF but with a negligible magnitude (“I felt relaxed”, R2<.02); no items showed significant education DIF. Yet no items met the a priori exclusion criteria. Thus, all five items were retained following IRT-related analyses.

Identifying fixed forms for norming

Twenty-one items were identified for norming from among the 34 items in the positive affect bank. These items reflected both high (I felt happy) and low (I felt peaceful) activated positive affect, and they were correlated r=0.99 with the full bank and r=0.89 with the modified PANAS-positive subscale less item content overlap.

Life Satisfaction

Testing assumptions for IRT

Fifty items were included in this domain. Item-total correlations showed one item had correlation <0.3, three were between 0.3 and 0.4 and ranged from 0.43 to 0.82 for the rest of 46 items. In EFA, seven factors had eigenvalues > 1 with one factor before the elbow in the scree plot, explaining 45.6% of total variance. The second factor explained 7.7% of the total variance and the remaining factors explained < 5% of total variance. Factor loadings of items implied two potential factors among these items. The research team reviewed the results and decided to removed 10 items with low loadings on the first two factors from the item pool and group the remaining items into two factors: Life Satisfaction (item n=21) and Meaning and Purpose (item n=18). Five items were removed from life satisfaction due to content redundancy, resulting in a total of 16 items included in further analyses. CFA results confirmed the unidimensionality of these 16 items with CFI=0.99, TLI=0.98, RMSEA=0.081. No potential locally dependent item pairs were found with all residual correlations < 0.15. Thus, the proposed life satisfaction bank contains locally independent items and is essentially unidimensional for purposes of scaling with IRT models.

Estimating item parameters

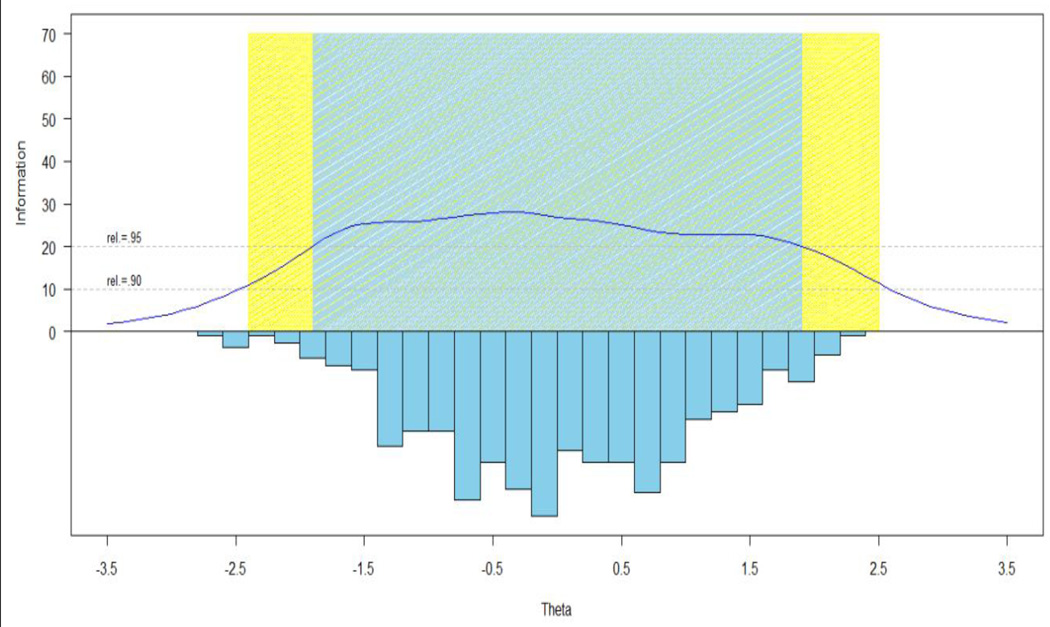

In IRT analyses, all items had acceptable fit (p>0.01). Slope parameters ranged from 0.9 (I am satisfied with my health) to 4.1 (I am satisfied with my life). Threshold parameters ranged from −3.0 (My life is better than most people) to 3.1 (I am satisfied with my health). Figure 2 shows 99% of participants were measured in a very precise manner (2% with reliability between 0.9 and 0.95; 97% with a reliability ≥ 0.95), indicating participants’ life satisfaction is reliably measured across the construct continuum.

Figure 2.

Precision Levels across the Life Satisfaction Measurement Continuum

Analyzing DIF

No items had significant DIF on “age”, “education”, or “gender”. Thus, we concluded the age, education, and gender of participants had no substantive impact on the measurement of life satisfaction with these items.

Identifying fixed forms for norming

The items selected for norming from among the 16 items in the life satisfaction bank included twelve-items comprised of the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale [40] and the seven-item Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale [41]. The correlations with the full-length item bank, excluding their own scale items, were r=0.83 and 0.87 for the Satisfaction with Life Scale and the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale, respectively. The two life satisfaction scales were correlated r=0.86 with each other.

Meaning

Testing assumptions for IRT

As stated above, an EFA identified a Meaning & Purpose factor comprised of 18 items. A subsequent CFA suggested acceptable fit indices (CFI=0.94 and TLI=0.98), yet RMSEA value (0.131) was higher than we expected. Borderline residual correlations were found in two item pairs: “I don't care very much about the things I do” versus “Most of what I do seems trivial and unimportant to me” (r=0.179) and versus “I value my activities a lot” (r=0.177). These items were provisionally retained for norming data collection, meaning their item-level properties would be examined in the norming sample to guide final decisions about whether to include or exclude them. The proposed meaning and purpose item bank is essentially free of locally dependent items and sufficiently unidimensional for purposes of scaling with IRT models.

Estimating item parameters

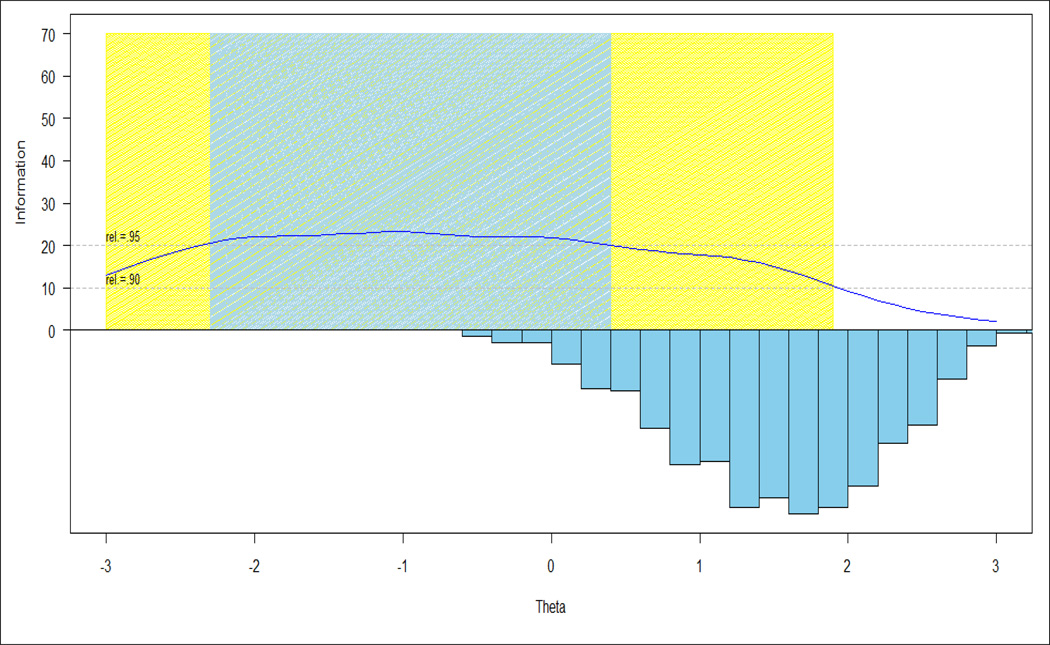

All items had acceptable fit (p >0.01) Slope parameters ranged from 1.2 (I value my activities a lot) to 2.8 (My life has no clear purpose). Threshold parameters ranged from −5.4 (I value my activities a lot) to 2.0 (My daily life is full of things that are interesting to me). Figure 3 shows about 29.5% of participants had reliability associated with their theta between 0.9 (included) and 0.95, and 69% ≥ 0.95. These items measured meaning and purpose with good precision across the continuum of the meaning and purpose construct.

Figure 3.

Precision Levels across the Meaning & Purpose Measurement Continuum

Analyzing DIF

One item had significant but negligible DIF on “age” (“My life has been productive”; R2 =0.0121). No items had significant DIF on either “education” or “gender”. Therefore, we concluded that participants’ age, education, and gender had no substantive impact on the measurement of meaning and purpose with these 18 items.

Identifying fixed forms for norming

Based on a review of the information function of the individual items, eight of the most informative items across the meaning and purpose continuum were selected from the 18-item meaning and purpose bank for further testing during norming. These items were correlated r=0.97 with the full bank and r=0.81 with the Presences of Meaning subscale of the modified Meaning in Life Questionnaire [18] less item content overlap.

Discussion

As a result of the NIH Toolbox process, we identified three measurable concepts of positive affect, life satisfaction, and meaning and purpose within the subdomain of PWB and developed and calibrated three item banks using IRT models. These banks showed equivalence of measurement properties across age, education, and gender and can be administered in the form of CATs or used to create static short forms to assess PWB concepts among adults to minimize response burden through more efficient assessments without compromising reliability

Most measures of positive affect assess activated emotion [10] yet the positive affect bank reflects high and low activated positive affect. The arousing nature of an emotion and not just its valence is potentially a very important distinction for improving our understanding about the relationship between PWB and health outcomes in general and between positive emotions and health outcomes more specifically. A review by Burgdorf and Panksepp [42] suggested that low and high activated positive affect are represented by separate but partially overlapping neuroanatomical substrates in the brain. Moreover, Christie and Friedman [43] found that low and high activated positive affect were associated with two different profiles of autonomic nervous system activation. In our sample, the first factor for positive affect was characterized by items describing high activation (I felt joyful, I felt delighted) and the second factor was characterized by items describing low activation (I felt peaceful, I felt at ease). A third factor was comprised of items reflecting cognitive engagement (I felt attentive, I felt interested). Despite the occurrence of three group factors, scores were sufficiently unidimensional to justify a single positive affect score.

The initial life satisfaction item pool was comprised of both general- and domain-specific life satisfaction items. Yet most domain-specific life satisfaction items were too specific (e.g., I am satisfied with my present job or work) and did not meet the measurement criteria to be included in the final item bank. This is not surprising since people can be satisfied with their life overall and yet simultaneously satisfied and dissatisfied with discrete parts of their life.[44];[45].

Meaning and purpose encompasses a range of related and somewhat distinct themes, including: a sense of comprehension, understanding, and coherence regarding life [46]; the feeling that life is worthwhile, significant, and matters [18]; and engagement in personally valued activities, a sense of purpose [47]. These themes are more abstract and somewhat esoteric terminology of meaning and purpose items relative to the more concrete and straightforward terminology of positive affect and life satisfaction items. We thus were not surprised with the less precise measurement of this item bank compared to other two. Additional work is needed to enhance the measurement precisions across the continuum.

This work had some limitations. An NIH Toolbox aim is to include concepts relevant to health and aging across the lifespan. We have not yet qualitatively tested how well these concepts resonate with community-dwelling adults. However, given the growing national and international interest in identifying and measuring well-being [45; 48–52] and our selection of items and measures that are among some of the more commonly used indices of PWB, we believe these items capture relevant dimensions of PWB among adults of diverse backgrounds. Additional data collection with a population-based sample will enhance the representativeness of this data. The NIH Toolbox normative data will allow us to more closely examine the generalizability of these results beyond this current sample. Despite these limitations, these measures provide a means to follow the evolution of emotional health concepts such as positive affect, life satisfaction, and meaning and purpose throughout adulthood. This would represent a significant advance in measurement and enhance the impact of future research on PWB and health outcomes.

In summary, the conceptualization of PWB and development of scales and item banks for positive affect, life satisfaction, and meaning and purpose has yielded robust self-report assessment tools. The scales and item banks for PWB provide the flexibility, efficiency, and precision necessary for the NIH Toolbox use in future health-related longitudinal epidemiological studies and prevention or intervention trials. It is anticipated the large general population survey already underway will provide more demographically specific normative data and permit across (Cognitive, Motor, Sensory) and within domain comparisons (Negative Affect, Stress & Self-Efficacy, and Social Relationships), yielding additional, informative data about the utility of these new measures and providing promise of greater standardization of measurement for these important, health-relevant concepts.

Acknowledgments

This project is funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the Blueprint for Neuroscience Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHS-N-260-2006-00007-C. Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIH grants KL2RR025740 from the National Center for Research Resources and 5K07CA158008-01A1 from the National Cancer Institute. The authors would like to thank the subdomain consultants, Felicia Huppert, PhD, Alice Carter, PhD, Marianne Brady, PhD, Dilip Jeste, MD, Colin Depp, PhD, Bruce Cuthbert, PhD, and members of the NIH project team, Gitanjali Taneja, Ph.D., and Sarah Knox, Ph.D., who provided critical and constructive expertise during the development of the NIH Toolbox Emotion measurement battery.

Study Funding: Supported by federal funds from the Blueprint for Neuroscience Research, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHS-N-260-2006-00007-C.

Appendix A: Toolbox Psychological Well-Being Adult Item Banks

| Positive Affect |

|---|

| 1 I felt cheerful. |

| 2 I felt attentive. |

| 3 I felt relaxed. |

| 4 I felt delighted. |

| 5 I felt inspired. |

| 6 I felt fearless. |

| 7 I felt happy. |

| 8 I felt joyful. |

| 9 I felt excited. |

| 10 I felt proud. |

| 11 I felt lively. |

| 12 I felt at ease. |

| 13 I felt enthusiastic. |

| 14 I felt determined. |

| 15 I felt interested. |

| 16 I felt confident. |

| 17 I felt able to concentrate. |

| 18 I was thinking creatively. |

| 19 I liked myself. |

| 20 My future looked good. |

| 21 I smiled and laughed a lot. |

| 22 I felt peaceful. |

| 23 I was able to reach down deep into myself for comfort. |

| 24 I felt a sense of harmony within myself. |

| 25 I generally enjoyed the things I did. |

| 26 I felt lighthearted. |

| 27 I felt satisfied. |

| 28 I felt good-natured. |

| 29 I felt useful. |

| 30 I felt optimistic. |

| 31 I felt interested in other people. |

| 32 I felt understood. |

| 33 I felt grateful. |

| 34 I felt content. |

Response options for the positive affect item bank were: “1 = Not at all, 2 = A little bit, 3 = Somewhat, 4 = Quite a bit, 5 = Very much”

| Life Satisfaction |

|---|

| 1 In most ways my life is close to my ideal. |

| 2 If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. |

| 3 I am satisfied with my life. |

| 4 So far I have gotten the important things I want in life. |

| 5 The conditions of my life are excellent. |

| 6 My life is going well. |

| 7 My life is just right. |

| 8 I would like to change many things in my life. |

| 9 I wish I had a different kind of life. |

| 10 I have a good life. |

| 11 I have what I want in life. |

| 12 My life is better than most people’s. |

| 13 I am satisfied with my family life. |

| 14 I am satisfied with my health. |

| 15 I am satisfied with my achievement of my goals. |

| 16 I am satisfied with my leisure. |

Response options for the life satisfaction item bank were: “1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Slightly disagree, 4 = Neither agree nor disagree, 5 = Slightly agree, 6 = Agree, 7 = Strongly agree” for items 1–5 and “1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree” for items 6–16.

| Meaning & Purpose |

|---|

| 1 I understand my life’s meaning. |

| 2 My life has a clear sense of purpose. |

| 3 I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful. |

| 4 I have discovered a satisfying life purpose. |

| 5 My life has no clear purpose. |

| 6 I generally feel that what I do in my life is valuable and worthwhile. |

| 7 I feel grateful for each day. |

| 8 My daily life is full of things that are interesting to me. |

| 9 There is not enough purpose in my life. |

| 10 To me, the things I do are all worthwhile. |

| 11 Most of what I do seems trivial and unimportant to me. |

| 12 I value my activities a lot. |

| 13 I don't care very much about the things I do. |

| 14 I have lots of reasons for living. |

| 15 I have a reason for living. |

| 16 My life has been productive. |

| 17 I feel a sense of purpose in my life. |

| 18 My life lacks meaning and purpose. |

Response options for the meaning and purpose item bank were: “1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly agree” for items 1–14, and “1 = Not at all, 2 = A little bit, 3 = Somewhat, 4 = Quite a bit, 5 = Very much” for items 15–18.

References

- 1.Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction. American psychologist. 2000;55(1):5. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aspinwall LG, Tedeschi RG. The Value of Positive Psychology for Health Psychology: Progress and Pitfalls in Examining the Relation of Positive Phenomena to Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;39(1):4–15. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danner DD, Snowdon DA, Friesen WV. Positive emotions in early life and longevity: findings from the nun study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80(5):804–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huppert F, Whittington J. Evidence for the independence of positive and negative well-being: Implications for quality of life assessment. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8(1):107–122. doi: 10.1348/135910703762879246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaillant GE. Aging well: surprising guideposts to a happier life from the landmark Harvard study of adult development. Boston: Little, Brown; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ostir GV, Markides KS, Black SA, Goodwin JS. Emotional well-being predicts subsequent functional independence and survival. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(5):473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Mortality: A Quantitative Review of Prospective Observational Studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(7):741–756. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818105ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(2):276–302. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salovey P, Rothman AJ, Detweiler JB, Steward WT. Emotional states and physical health. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):110–121. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S, Pressman SD. Positive Affect and Health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(3):122–125. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fava GA, Ruini C. Development and characteristics of a well-being enhancing psychotherapeutic strategy: well-being therapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2003;34(1):45–63. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(03)00019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keyes CLM, Haidt J. Flourishing : positive psychology and the life well-lived. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan RM, Huta V, Deci E. Living well: a self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9(1):139–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson D, Tellegen A. Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):219–235. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(6):925–971. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucas RE, Diener E, Suh E. Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71(3):616–628. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S, Kaler M. The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the Presence of and Search for Meaning in Life. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(1):80–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamberlain K, Zika S. Measuring meaning in life: An examination of three scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 1988;9(3):589–596. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steger M, Kashdan T. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2007;8(2):161–179. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershon RC, Cella D, Fox NA, Havlik RJ, Hendrie HC, Wagster MV. Assessment of neurological and behavioural function: the NIH Toolbox. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(2):138–139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowinski CJ, Victorson D, Debb SM, Gershon R. Surveying the End User Research Community: Input on NIH Toolbox criteria. Neurology. 2013;80(11 Supplement 3):S7–S12. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salsman JM, Butt Z, Pilkonis PA, Cyranowski JM, Zill N, Hendrie HC, Kupst MJ, Kelly M, Bode RK, Choi SW, Lai JS, Griffith JW, Stoney CM, Brouwers P, Knox SS, Cella D. Emotion assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80(11 Supplement 3):S76–S86. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai JS, Cella D, Choi SW, Junghaenel DU, Christodolou C, Gershon R, Stone A. How Item Banks and Their Application Can Influence Measurement Practice in Rehabilitation Medicine: A PROMIS Fatigue Item Bank Example. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92(10 Supplement):S20–S27. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D. Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS):depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klem M, Saghafi E, Abromitis R, Stover A, Dew M, Pilkonis P. Building PROMIS item banks: librarians as co-investigators. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(7):881–888. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9498-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roster CA, Rogers RD, Albaum G, Klein D. A comparison of response characteristics from web and telephone surveys. International Journal of Market Research. 2004;46(3):359–374. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Cella D, Gershon R, Shen J, Morales LS, Riley W, Hays RD. Representativeness of the PROMIS Internet Panel. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(11):1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D. Having a fit: impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT's unidimensionality assumption. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(4):447–460. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, Thissen D, Revicki DA, Weiss DJ, Hambleton RK, Liu H, Gershon R, Reise SP, Lai JS, Cella D. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–S31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement, No. 17. 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thissen D. MULTILOG (Version Windows 7.0) Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orlando M, Thissen D. Further examination of the performance of S-X2, an item fit index for dichotomous item response theory models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2003;27:289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bottomley A, de Graeff A, Groenvold M, Gundy C, Koller M, Petersen MA, Sprangers MA Group E. Q. o. L., & Quality of Life Cross-Cultural Meta-Analysis, G. A simulation study provided sample size guidance for differential item functioning (DIF) studies using short scales. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(3):288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zumbo BD. A handbook on the theory and methods of differential item functioning (DIF): Logistic regression modeling as a unitary framework for binary and Likert-type (ordinal) item scores. Ottawa, ON: Directorate of Human Resources Research and Evaluation, Department of National Defense; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi SW, Gibbons LE, Crane PK. lordif: An R Package for Detecting Differential Item Functioning Using Iterative Hybrid Ordinal Logistic Regression/Item Response Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;39(8):1–30. doi: 10.18637/jss.v039.i08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McDonald RP. Test Theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai JS, Crane PK, Cella D. Factor analysis techniques for assessing sufficient unidimensionality of cancer related fatigue. Quality of Life Research. 2006;15(7):1179–1190. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huebner ES. Initial Development of the Student's Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International. 1991;12(3):231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burgdorf J, Panksepp J. The neurobiology of positive emotions. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christie IC, Friedman BH. Autonomic specificity of discrete emotion and dimensions of affective space: a multivariate approach. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004;51(2):143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heller D, Watson D, Hies R. The role of person versus situation in life satisfaction: a critical examination. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(4):574–600. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kobau R, Zack MM, Sniezek J, Lucas RE, Burns A. Well-being assessment: An evaluation of well-being scales for public health and population estimates of well-being among US adults. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2010;2(3):272–297. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reker GT, Chamberlain K. Exploring existential meaning : optimizing human development across the life span. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheier M, Wrosch C, Baum A, Cohen S, Martire L, Matthews K, Schulz R, Zdaniuk B. The Life Engagement Test: Assessing Purpose in Life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(3):291–298. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diener E, Lucas R, Schimmack U, Helliwell J. Well-being for public policy. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallup Inc. Gallup World Poll: Wellbeing. 2011 Retrieved May 20, 2011, from http://www.gallup.com/poll/wellbeing.aspx.

- 50.OECD. Better Life Initiative: Measuring Well-being and Progress. 2011 Retrieved May 25, 2011, from http://www.oecd.org/document/0/0,3746,en_2649_201185_47837376_1_1_1_1,00.html.

- 51.Office for National Statistics. Working Paper: Measuring Societal Wellbeing in the UK. 2007 Retrieved December 15, 2011, from http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_social/Measuring-Societal-Wellbeing.pdf.

- 52.Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2009 Retrieved May 25, 2011, from http://www.stat.si/doc/drzstat/Stiglitz%20report.pdf.