Abstract

Objectives

We examined whether scores on a motion sensitivity questionnaire (MSQ) could distinguish between vestibular migraine (VM) and Meniere's disease (MD). As a secondary goal, we examined whether scores on the MSQ correlated with results from caloric testing.

Study Design

This study administered a telephone questionnaire to subjects who met clinical criteria for vestibular migraine, Meniere's disease, and controls.

Methods

A MSQ was administered to 20 subjects meeting American Academy of Otolaryngology (AAO) criteria for MD, 30 subjects meeting Neuhauser criteria for both probable vestibular migraine (pVM) and definite vestibular migraine (dVM), and 22 controls.

Results

The average score on the MSQ was 5.9 for VM, 4.25 for MD, and 0.4 for controls. Both VM and MD scored significantly higher than controls (p= 0.0001), but results were not statistically different from each other (p= 0.17). However, average score for subjects with dVM was 7.1, which was significantly higher than subjects with pVM, whose average score was 4.2 (p= 0.045), and higher than subjects with MD (p=0.048). When each question of the MSQ was analyzed, motion sensitivity to riding in a car was found to be significantly different between VM (average score 1.1) and MD (average score 0.5), with p value of 0.048. Scores of MSQ did not correlate with total eye speed on caloric testing.

Conclusions

Subjects with VM and MD had elevated levels of motion sensitivity compared to controls. Subjects with VM had more motion sensitivity to riding in a car than those with MD, but their TES were not different.

Keywords: vestibular migraine, motion sickness, motion sensitivity, Meniere's disease, vestibular testing, caloric testing, total eye speed, motion sensitivity questionnaire

Introduction

Vestibular migraine (VM) is responsible for a large proportion of people complaining of dizziness.1-3 Unfortunately, diagnosis can be difficult because many symptoms of vestibular migraine can overlap with other vestibular disorders. This is a particular concern with Meniere's disease (MD), because both diseases can share a history of episodic dizziness, hearing loss, sensitivity to food triggers, and headache.1,4-6 Distinction between the two conditions is important because treatment algorithms are generally quite different.1,7-10 This diagnostic dilemma has motivated a search for findings on either clinical history and exam or vestibular testing that can reliably distinguish the two conditions.11-14

Despite past efforts at identifying factors specific to each condition, the diagnosis often remains challenging. Here, we examined two possible measures for separating VM from MD. First, based on the observation that subjects with both migraine and VM have been noted to have higher motion sensitivity than normal subjects,15 we examined if results on a motion sensitivity questionnaire would be different between VM and MD. Second, based on reports that subjects with migraine have changes in the vestibulo-ocular reflex relative to normals,16,17 we compared responses to caloric stimulation between VM and MD.

Materials and Methods

After obtaining approval from the Washington University Institutional Review Board, we searched a database of all subjects who had completed caloric vestibular testing in the last ten years. We included only subjects strictly meeting the 1995 AAO criteria for Meniere's disease, and those who met criteria for “probable” and “definite” vestibular migraine according to criteria proposed by Neuhauser.18,19 According to these widely accepted criteria, a diagnosis of probable vestibular migraine (pVM) requires a history of episodic vertigo as well at least one of the following: migraine (satisfying the criteria of the International Classification of Headache Disorders20) or migrainous symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, migrainous headaches, or auras during vertigo attacks. A diagnosis of definite vestibular migraine (dVM) requires episodic vertigo, a history of migraine, and migrainous symptoms during two or more attacks of vertigo. A telephone interview was used to clarify symptoms to determine diagnosis when necessary after review of the clinical record; if a potential subject's diagnosis remained uncertain, he or she was excluded from further analysis. We collected a convenience sample of control subjects through word-of-mouth.

Exclusion criteria included a second diagnosed cause of dizziness, middle or inner ear surgery, pharmacologic ablation of the vestibular system, age younger than 18 years, inability to locate patient records, and subjects who met criteria for both VM and MD. Control subjects had no history of migraine, otologic or neurologic problems, or dizziness.

Participants were contacted by telephone and administered a motion sensitivity questionnaire (MSQ)based on a visual analogue scale developed by Dannenbaum querying motion sensitivity in several situations (Table 1).21 Questions were asked in the following way: “Do you get motion sick from (specific situation)?” Scores were defined as 0 being “no”, 1 was “somewhat”, 2 was “a lot”, and 3 was “so much so that the activity is avoided.” For the last question, “Are you a motion sensitive person?” a score of 3 was defined as “so much so that it interferes with daily life.” Motion sensitivity was defined as any of the following symptoms: feeling ill, vomiting, feeling hot or sweaty, headaches, change in skin color, mouth watering, drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, or avoiding the situation.

Table 1.

Scores on the Motion Sensitivity Questionnaire. P-value refers to significance of difference between subjects with vestibular migraine and those with Meniere's.

| Vestibular migraine | Meniere's | Control | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking in a supermarket | 0.47 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.97 |

| Being a passenger in a car | 1.07 | 0.5 | 0.18 | 0.048 |

| Being under fluorescent lights | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.5 |

| Being at a busy intersection | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.13 |

| Being in a shopping center | 0.23 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.61 |

| Going on escalators | 0.57 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.26 |

| Movies in a theater | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 0.39 |

| Seeing patterned floors | 0.67 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Watching television | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0 | 0.98 |

| Are you a motion sensitive person? | 1.2 | 1.15 | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| Overall Score | 5.88 | 4.25 | 0.37 | 0.17 |

All subjects had previously undergone caloric testing using a Brookler-Grams (DA-200, Cosa Mesa, CA) closed loop system with standard bithermal irrigations. Responses were recorded using an infrared video oculographic system (Micromedical Technologies, Chatham, IL, USA). During all testing, mental tasking was employed. Total eye speed (TES) was measured as the sum of peak slow-phase velocity in both ears in both warm and cool conditions. Caloric testing was performed in an identical way on normal subjects. Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism software. Given relatively small sample sizes, nonparametric statistical tests were used, and a p-value of 0.05 was chosen to indicate significance.

Results

Participants included 30 subjects (24 female) with vestibular migraine, 20 subjects (11 female) with Meniere's disease, and 22 controls (14 female). Of the subjects with vestibular migraine, 17 had dVM and 13 had pVM. The average age of the combined VM group was 49 (SD=12), the Meniere's group was 57 (SD=13), and the control group was 49 (SD=22). 3 subjects met criteria for both VM and MD and were therefore excluded from participation.

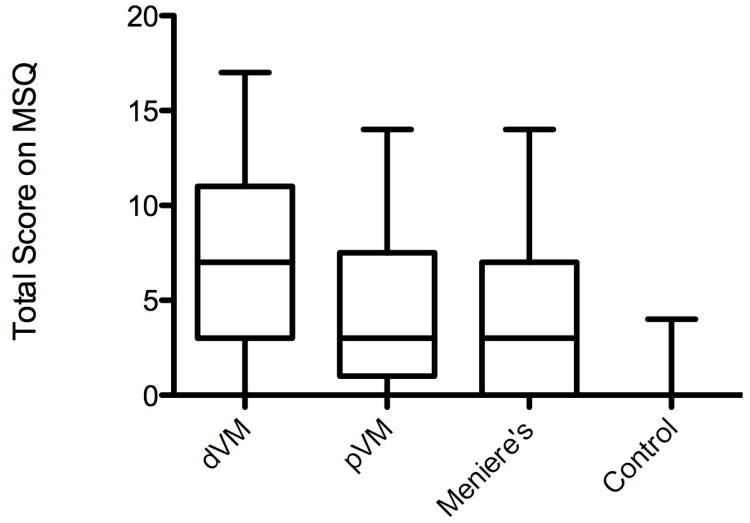

Mean total scores on the motion sensitivity questionnaire were 5.87 for VM, with 7.12 for dVM and 4.23 for pVM, 4.25 for MD, and 0.37 for controls. Median total score was 4.5 for VM (range 0.0 to 17.0), with 7.0 for dVM (range 0.0 to 17.0) and 3.0 for pVM (range 0.0 to 14.0), 3.0 for MD (range 0.0 to 14.0) and 0.0 for controls (range 0.0 to 4.0).The difference among these groups was statistically significant (Kruskal-Wallis test, p<0.0001) (Figure 1). Planned pairwise comparisons showed that MSQ scores were higher among subjects with dVM than those with pVM (p=0.045) or MD (p=0.048). Scores for VM (combining subjects with pVM and those with dVM) and MD were not significantly different from each other (p=0.172) but both were higher than controls (p<0.0001 for both).Analysis of the individual questions of the MSQ with multiple planned pairwise comparisons between VM and MD showed that only motion sensitivity to riding in a car had a statistically significant difference, with mean VM score 1.07 and mean MD score 0.50 (p =0.048) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Total score on the motion sensitivity questionnaire. From left to right: definite vestibular migraine, probable vestibular migraine, Meniere's disease, and normal controls. Middle quartiles represented by box, with line representing mean. Maximum and minimum values represented by lines above and below box.

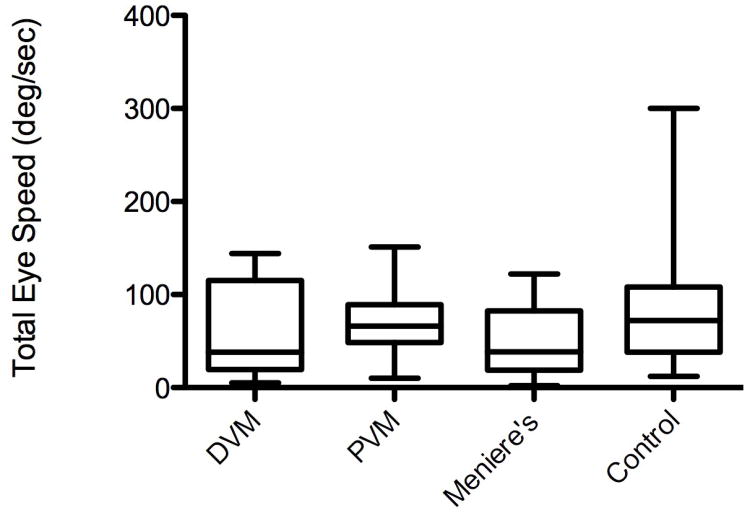

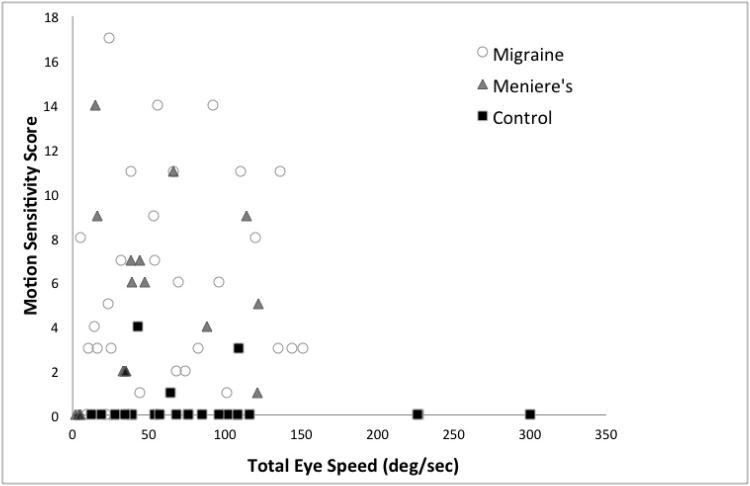

Caloric testing demonstrated a mean TES of 64.1 deg/sec in VM, 49.9 deg/sec in MD, and 90.0 deg/sec in controls. TES values were similar for dVM (mean TES 61.5 deg/sec) and pVM (mean TES 67.5 deg/sec).Median values for TES were 55.5 deg/sec for VM (range 5 to 151), with dVM 138 deg/sec (range 5 to 144) and pVM 66 deg/sec (range 10 to 151), MD 38.5 deg/sec (range 2 to 122) and controls 72 deg/sec (range 12 to 300).There was no significant difference among the three groups (Kruskal-Wallis, p=0.122) (Figure 2). Total score on the MSQ, taken across all groups, did not correlate with TES (Spearman r =0.018, p=0.88) (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Total eye speed on caloric testing. From left to right: definite vestibular migraine, probable vestibular migraine, Meniere's disease, and normal controls. Middle quartiles represented by box, with line representing mean. Maximum and minimum values represented by lines above and below box.

Figure 3.

Motion sensitivity score versus total eye speed. Migraine, open circles; Meniere's, gray triangles; normal controls, black squares.

Mean caloric asymmetry, defined by Jongkees formula, was 23.7% for VM, 40.1% for MD, and 17.0% for control subjects. Asymmetry varied significantly among groups (Kruskal- Wallis, p=0.0007), with Dunn's multiple comparison test showing significance for MD versus VM and MD versus control, but not for VM versus control. The percentage of subjects in each group with asymmetry as defined by a cutoff value of 30%, and excluding subjects with bilaterally reduced responses (TES less than 20 degree/second), was 23% for VM, 88% for MD, and 14% for controls. There was no significant correlation between scores on the MSQ and caloric asymmetry (Spearman r= 0.094, p=0.73).

Discussion

Motion Sensitivity

We found that subjects meeting a strict definition for vestibular migraine have increased motion sensitivity. This is consistent with several previous studies. Jeong et al. used the Motion Sensitivity Susceptibility Questionnaire (MSSQ) and found that patients with vestibular migraine had higher scores on the questionnaire than subjects with migraine alone, who in turn had higher scores than normal controls.15 Drummond administered a motion sensitivity susceptibility questionnaire to migraineurs and control subjects, and also found significant differences.22 In that case, further analysis of the data by specific activity demonstrated significant differences in certain challenging situations, such as travelling in cars and buses and watching wide screen movies, but not in others, such as traveling in trains, aircraft, or boats.

We built on this previous work by subdividing patients with vestibular migraine into those that met criteria for dVM and pVM. We found that those with dVM did have more motion sensitivity than those with pVM. This result helps provide independent validation of the Neuhauser criteria for separating these groups.19 Further work is necessary to delineate if quantitative evaluation of motion sensitivity could assist clinicians to make diagnostic, therapeutic, or prognostic decisions.

A novel and important finding of our study was the observation that subjects with Meniere's disease have greater motion sensitivity than control subjects. This was demonstrated not only by increased sensitivity to the various scenarios in the questionnaire, but also with increased self perception of being a motion sensitive person. Specifically, there was no significant difference between VM and MD for the question “Do you think you are a motion sensitive person?”

The reason for elevated motion sensitivity in Meniere's disease is not clear. We specifically excluded three subjects who fulfilled the criteria for both VM and MD, suggesting that carrying a mutual diagnosis is an unlikely explanation. Another possibility is that the elevated levels of peripheral asymmetry characteristic of Meniere's patients might in turn predispose to motion sensitivity. Our data do not strongly support this explanation, however, as we found that the amount of asymmetry was not related to the score on the motion sensitivity questionnaire. The finding that motion sickness, which may be primarily a central phenomenon, is an important feature of Meniere's disease raises that possibility that some of the symptoms of Meniere's (for instance, imbalance between acute episodes of vertigo) might not be fully explained by peripheral causes. This could provide important new insights into its pathogenesis and treatment.

Although the motion sensitivity questionnaire was unable to distinguish between MD and VM, there were small but statistically significant differences between dVM and pVM, and between dVM and MD. However, the small size of these differences would question the ability of the questionnaire to make clinical distinctions between those groups. Analysis of the individual questions showed that only motion sensitivity to riding is a car separated VM from MD. This raises the possibility that a more refined questionnaire might be more successful at distinguishing the two conditions. For example, questions regarding motion sensitivity as a child have anecdotally been suggested as good markers of vestibular migraine.

Caloric Responses

Various authors have investigated the results of vestibular tests for subjects with vestibular migraine and Meniere's disease to see if unique results can be used to diagnose them and distinguish amongst them.12,23-31 For vestibular migraine, one large study evaluated 523 patients with dVM, pVM, vestibular disorder coexisting with migraine, and control subjects. That study did not find any parameters on testing that separated VM from controls.25 In contrast, Arriaga et al. found abnormal high gain on visually-enhanced vestibulo-ocular reflex testing in 71% of VM subjects versus 5% of controls.32 For Meniere's disease, the most consistently reported abnormality on testing is caloric asymmetry, which is found 50-66% of the time.29 Dimitri et al. investigated whether an algorithm derived from a multivariate statistical analysis could distinguish between VM and MD. He found reduced responses to caloric stimulation in patients with Meniere's disease compared with vestibular migraine.12 They used this test, along with gain, time constant, and asymmetry on sinusoidal harmonic acceleration, to achieve a 91% joint classification rate in patients with Meniere's and vestibular migraine. We did not find any significant differences between our test groups based on TES. We did, however, find that our subjects with MD had high levels of caloric asymmetry, which is a helpful diagnostic clue in separating them from VM.

Some anecdotal observations have suggested that subjects with vestibular migraine have elevated TES. However, we found that the overall caloric responses of subjects with vestibular migraine were in fact not significantly higher than controls or subjects with Meniere's disease. One way to reconcile our findings with previous anecdotal observations of increased TES is that some of our subjects with VM were particularly sensitive to caloric stimulation, generating both very fast eye movements and significant discomfort leading to premature termination of the test. Other investigators have reported results that suggest this as a plausible explanation. Vitkovic et al. compared patients with VM to those with other causes for dizziness, finding that the indicator best able to distinguish between the groups an emetic response to testing.25 Mallison and Longridge found higher caloric scores in subjects who were bothered by caloric testing, arguing that there may be some correlation between symptomatology and TES.17 We cannot specifically evaluate that possibility, as subjects who did not complete vestibular testing were not included in our study population.

Recent psychophysical work has investigated the relationship between the subjective detection threshold for head movement and reflexive eye speed in response to that movement.33,34 Our data offered the opportunity to determine if an analogous relationship could be demonstrated between scores on a subjective motion sensitivity questionnaire and measurement of reflexive eye movements to caloric stimulation. Some previous studies have found increased caloric response and prolonged time constants on step velocity testing in subjects with motion sensitivity.15,16 However, we did not find any correlation between them, consistent with later studies showing no relationship between eye speed and motion sensitivity.17

Conclusion

We made the novel observation that subjects with Meniere's disease have more motion sensitivity than controls. Overall a motion sensitivity questionnaire was unable to distinguish between subjects with vestibular migraine and those with Meniere's disease, but motion sensitivity to riding in a car was different between the groups. Total eye speed was not elevated among subjects with vestibular migraine compared to those with Meniere's disease or normal subjects.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH NIDCD K08 006869 (TEH). Belinda Sinks, AuD and Nicholas N-Y Chang assisted with data collection.

Source of financial support: NIH NIDCD K08 006869

This work was funded through NIH grant NIH NIDCD K08 006869.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none (for both authors)

Financial Disclosure: There are no other financial disclosures or other financial interests to report for either author.

Poster presented at Combined Otolaryngology Section Meeting Triological Section in Orlando, Florida, April 10-14th, 2013

References

- 1.Eggers SD. Migraine-related vertigo: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci. 2006;6:106–15. doi: 10.1007/s11910-996-0032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuhauser H, Leopold M, von Brevern M, Arnold G, Lempert T. The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology. 2001;56:436–41. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neuhauser HK, von Brevern M, Radtke A, et al. Epidemiology of vestibular vertigo: a neurotologic survey of the general population. Neurology. 2005;65:898–904. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000175987.59991.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radtke A, Lempert T, Gresty MA, Brookes GB, Bronstein AM, Neuhauser H. Migraine and Meniere's disease: is there a link? Neurology. 2002;59:1700–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036903.22461.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rassekh CH, Harker LA. The prevalence of migraine in Meniere's disease. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:135–8. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brantberg K, Baloh RW. Similarity of vertigo attacks due to Meniere's disease and benign recurrent vertigo, both with and without migraine. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:722–7. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.556661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson GD. Medical management of migraine-related dizziness and vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:1–28. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199801001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reploeg MD, Goebel JA. Migraine-associated dizziness: patient characteristics and management options. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:364–71. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200205000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sajjadi H, Paparella MM. Meniere's disease. Lancet. 2008;372:406–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honaker J, Samy RN. Migraine-associated vestibulopathy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol. 2008;16:412–5. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32830a4a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neff BA, Staab JP, Eggers SD, et al. Auditory and vestibular symptoms and chronic subjective dizziness in patients with Meniere's disease, vestibular migraine, and Meniere's disease with concomitant vestibular migraine. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:1235–44. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31825d644a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitri PS, Wall C, 3rd, Oas JG, Rauch SD. Application of multivariate statistics to vestibular testing: discriminating between Meniere's disease and migraine associated dizziness. J Vest Res. 2001;11:53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shepard NT. Differentiation of Meniere's disease and migraine-associated dizziness: a review. J Am Acad Audiol. 2006:69–80. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.17.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cha YH, Brodsky J, Ishiyama G, Sabatti C, Baloh RW. The relevance of migraine in patients with Meniere's disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:1241–5. doi: 10.1080/00016480701242469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong SH, Oh SY, Kim HJ, Koo JW, Kim JS. Vestibular dysfunction in migraine: effects of associated vertigo and motion sickness. J Neurol. 2010;257:905–12. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lidvall HF. Mechanisms of motion sickness as reflected in the vertigo and nystagmus responses to repeated caloric stimuli. Acta Otolaryngol. 1962;55:527–36. doi: 10.3109/00016486209127388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mallinson AI, Longridge NS. Motion sickness and vestibular hypersensitivity. J Otolaryngol. 2002;31:381–5. doi: 10.2310/7070.2002.34575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the diagnosis and evaluation of therapy in Meniere's disease. Otolaryng Head Neck. 1995;113:181–5. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radtke A, Neuhauser H, von Brevern M, Hottenrott T, Lempert T. Vestibular migraine--validity of clinical diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:906–13. doi: 10.1177/0333102411405228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dannenbaum E, Chilingaryan G, Fung J. Visual vertigo analogue scale: an assessment questionnaire for visual vertigo. J Vest Res. 2011;21:153–9. doi: 10.3233/VES-2011-0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drummond PD. Triggers of motion sickness in migraine sufferers. Headache. 2005;45:653–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celebisoy N, Gokcay F, Sirin H, Bicak N. Migrainous vertigo: clinical, oculographic and posturographic findings. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:72–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teggi R, Colombo B, Bernasconi L, Bellini C, Comi G, Bussi M. Migrainous vertigo: results of caloric testing and stabilometric findings. Headache. 2009;49:435–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vitkovic J, Paine M, Rance G. Neuro-otological findings in patients with migraine- and nonmigraine-related dizziness. Audiol Neuro-Otol. 2008;13:113–22. doi: 10.1159/000111783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Furman JM, Marcus DA, Balaban CD. Migrainous vertigo: development of a pathogenetic model and structured diagnostic interview. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:5–13. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000053582.70044.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boldingh MI, Ljostad U, Mygland A, Monstad P. Vestibular sensitivity in vestibular migraine: VEMPs and motion sickness susceptibility. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:1211–9. doi: 10.1177/0333102411409074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Brevern M, Zeise D, Neuhauser H, Clarke AH, Lempert T. Acute migrainous vertigo: clinical and oculographic findings. Brain. 2005;128:365–74. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams ME, Heidenreich KD, Kileny PR. Audiovestibular testing in patients with Meniere's disease. Otolaryng Clin N Am. 2010;43:995–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Black FO, Kitch R. A review of vestibular test results in Meniere's disease. Otolaryng Clin N Am. 1980;13:631–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palomar-Asenjo V, Boleas-Aguirre MS, Sanchez-Ferrandiz N, Perez Fernandez N. Caloric and rotatory chair test results in patients with Meniere's disease. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:945–50. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000231593.03090.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arriaga MA, Chen DA, Hillman TA, Kunschner L, Arriaga RY. Visually enhanced vestibulo-ocular reflex: a diagnostic tool for migraine vestibulopathy. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1577–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000231308.48145.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seemungal BM, Gunaratne IA, Fleming IO, Gresty MA, Bronstein AM. Perceptual and nystagmic thresholds of vestibular function in yaw. J Vest Res. 2004;14:461–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haburcakova C, Lewis RF, Merfeld DM. Frequency dependence of vestibuloocular reflex thresholds. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:973–83. doi: 10.1152/jn.00451.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]