Abstract

Rationale

A functional polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) has previously been related to upper airway pathology, but its contribution to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a highly prevalent sleep disorder in older adults, remains unclear.

Objectives

We aimed to investigate the relationship between Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) and genetic variations in the promoter region of the 5-HTTLPR in older adults.

Methods and Measurements

DNA samples from 94 community-dwelling older adults (57% female, mean age 72±8) were genotyped for the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism. All participants were assessed in their homes with full ambulatory polysomnography, in order to determine AHI and related parameters such as hypoxia, sleep fragmentation, and self-reported daytime sleepiness.

Main Results

The 5-HTT l allele was significantly associated with AHI (p=0.019), with l allele carriers displaying a higher Apnea-Hypopnea Index than s allele homozygotes. A single allele change in 5-HTTLPR genotype from s to l resulted in an increase of AHI by 4.46 per hour of sleep (95% CI, 0.75-8.17). The l allele was also associated with increased time during sleep spent at oxygen saturation levels below 90% (p=0.014).

Conclusions

The observed significant association between the 5-HTTLPR l allele and severity of OSA in older adults suggests that the l allele may be important to consider when assessing for OSA in this age group. This association may also explain some of the observed variability among serotonergic pharmacological treatment studies for OSA, and 5-HTT genotype status may have to be taken into account in future therapeutic trials involving serotonergic agents.

Keywords: 5-HTTLPR, sleep apnea, OSA, aging, sleep

Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a highly prevalent sleep disorder in the elderly (1), and prevalence increases with advancing age (2). It is an independent risk factor for numerous disorders associated with substantial morbidity, including cardiovascular disease and diabetes (3-5), as well as neurobehavioral impairment, including cognitive dysfunction (6). Several epidemiological studies demonstrate familial aggregation of OSA (7-10), explaining up to 40% of the variance in the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) of OSA patients. Identifying genetic factors associated with OSA represents an important step towards identification of those at increased risk for OSA and its complications. A recent review and meta-analysis of the state of the science of the genetics of OSA revealed few candidate genes with replicated gene association studies (11), further highlighting the need for more work in this area.

Genes related to the serotonergic system are among the prime candidates for involvement in OSA. Apart from its well-defined involvement in sleep regulatory processes, serotonin is implicated in the control of respiration during sleep (12-14). A role for serotonin in the control of upper airway activity during sleep has been demonstrated in animal and human studies. Serotonergic facilitation of motoneuronal activity in the ventilatory and upper airway dilator muscles (15, 16) is exerted through an excitatory influence on hypoglossal and trigeminal motoneurons, among others. During sleep, this serotonergic drive is reduced which in turn is suggested to contribute to the observed state-dependent upper airway collapse in OSA (17, 18).

This upper airway collapsibility due to decreased availability of serotonin may be exacerbated with age. Behan et al. (19) found older rats displayed significantly fewer serotonin immunoreactive axons and boutons in the hypoglossal nucleus than younger rats, suggesting an age-related decrease of serotonin availability, potentially increasing upper airway instability during sleep and underlying the observed increase in OSA prevalence in older adults.

The serotonin transporter (5-HTT) controls the re-uptake of serotonin from the extra-cellular space, thus regulating the duration and strength of the interactions between 5-HT and its receptors. Genetic variations in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) consist of a 44-base pair (bp) allelic insertion (long or l allele) or deletion (short or s allele), regulating the transcription of the serotonin transporter and the efficacy of 5-HT uptake among the three genotypes, ll, ls and ss (20). The s allele is associated with lower levels of serotonin uptake and lower transcriptional efficiency of the serotonin transporter (21). While it is unclear whether the differential impact of the 5-HTT on 5-HT availability translates into the in vivo brain (22-26), some imaging studies have demonstrated that ll carriers have an increased availability of raphe 5-HT transporters compared to s allele carriers (27).

Some initial studies have been conducted to examine a possible association between 5-HTTLPR and OSA. Yue et al. (28) did not observe any differences in 5-HTTLPR genotype and allele frequencies between 254 middle-aged OSA patients and 338 healthy controls in a Chinese Han population, of similar age, sex, BMI and education. However, when stratified by gender, male patients did have higher frequency of the l allele, and those who were carriers of the s allele had a significantly lower apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). However, the 5-HTT promoter allele distribution varies widely by ethnicity, complicating comparisons between studies (29). In a Turkish sample, no differences in 5-HTTLPR genotypes or allele frequencies were observed between 27 middle-aged OSA patients and 162 healthy controls; however, when patients were separated by sex, males were again found to have a significantly greater frequency of the l allele than the controls (30). Neither study, however, investigated the association between 5-HTT genotype and AHI as a continuum, and thus did not assess a full spectrum of apnea levels. Given the role of 5-HT in the functional integrity of respiration during sleep and its suggested decreased availability in aging, it is reasonable to consider that the 5-HTTLPR gentoype may impact the severity of sleep-disordered breathing in a geriatric population. In this study, we aimed to investigate of the relationship of genetic variations in the promoter region of the 5-HTTLPR genotype and allele frequency with level of AHI and related sleep parameters, in a community-dwelling older adult sample.

Methods

Study population

Subjects were 94 community-dwelling older adults, recruited through advertisements, the Stanford Aging Research and Clinical Center, and local senior centers to this investigation of sleep and behavioral outcomes. All provided informed consent in accordance with Stanford University IRB regulations. The 54 females and 40 males were all Caucasian, between 60 and 90 years of age (M=71.51; SD = 7.8). They had a mean 16.42 years of education (SD = 2.6). Initial evaluation included demographics, self-reported current and past medical status, the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR. Individuals with a previously diagnosed OSA treated by CPAP or BiPAP were excluded, as were those presenting with uncontrolled medical conditions. Patients were considered to have controlled medical conditions if they were not acutely symptomatic and were on stable treatment regimens e.g. disorder such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension. Medications were recorded at initial assessment. All subjects taking any sleep medication, prescription or non-prescription, were excluded from participation. All other medications were recorded, included dose and duration. Both past and current alcohol usage and smoking were documented. Individuals were furthermore excluded if they had a MMSE<26, a diagnosis of possible or probable dementia or any Axis I disorders currently, or within the past 2 years, including major depression. Upon entry into the study, whole blood was drawn and transported to the genetics laboratory where DNA was extracted upon arrival. All participants subsequently underwent the following sleep assessment.

Assessment of AHI and other sleep parameters

Ambulatory polysomnography was recorded using the Compumedics Safiro® ambulatory polysomnography (PSG) monitoring system. Recordings had to produce at least 4 hours of acceptable data. An experienced board certified sleep technician who was blind to any information pertaining to the study scored sleep stages by manual, visual analysis of the polysomnograph records according to the standard conventions (31). Respiratory events and periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS) were hand-scored using standard definitions, and related sleep parameters derived as recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (32, 33). Subjective self-report was employed to assess daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale, ESS (34)) and overall sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, PSQI (35)).

Genotyping

We extracted DNA from 200μl of frozen blood using the Qiagen DNeasy Kit (Cat.#69506) and processed as described previously (36). Oligonucleotide primers flanking the 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region, corresponding to the nucleotide positions -1416 to -1397 (stpr5, 5’-GGC GTT GCC GCT CTG AAT GC) and -910 to -888 (stpr3, 5’-GAG GGA CTG AGC TGG ACA ACC AC) of the 5-HTT gene 5’-flanking regulatory region were utilized to generate 484bp or 528bp fragments. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification was conducted in a final volume of 30μl consisting of 50ng of genomic DNA, 50ng each of sense and antisense primers, 15μl of Taq PCR Master mix (Qiagen, Cat.#201445), 10% DMSO and 1M Betaine. Annealing was conducted at 61°C for 30s, extension at 72°C for 1 minute, and denaturation at 95°C for 30s for a total of 35 cycles. PCR products were electrophoresed through 5% Polyacrylamide gel (Acrylamide/bis-Acrylamide ratio 19:1) at 120 V for 60 min. A 100bp marker was utilized for measuring the PCR product size for the l allele and the s allele. Two independent observers assigned the alleles and genotypes. They were blind to any information pertaining to the study volunteers.

Statistical analysis

Regression analysis was employed to examine the relation between 5-HTT and AHI. To control for age as a potential confounding factor, we included age in addition to the number of l alleles as the independent variables into the model, with AHI as the primary outcome variable. In secondary analyses, linear regression was conducted for additional OSA and sleep related outcomes, including time asleep spent at oxygen saturations below 90% (SaO2<90%, in minutes), sleep fragmentation (Wake-After-Sleep-Onset, WASO, in minutes), sleep architecture (Rapid Eye Movement Sleep (REM), light slow wave sleep (Stage 1 and Stage 2), deep slow wave sleep (Stage 3 and Stage 4), all expressed in % total sleep time (TST), and self-report daytime sleepiness (ESS) and sleep quality (PSQI). We also employed regression to test for impact of all potential covariates, including BMI, gender, and number of medications. Since 5HTTLPR genotype has been associated with both smoking and drinking, we recorded both (37). Only four subjects smoked and analyses revealed no difference between our findings with and without these four subjects included. We utilized the lifetime drinking questionnaire to assess for current and past alcohol use (number of drinks per week number). When past and current drinking were included as covariates, no differences in our findings were observed.

All statistical tests were conducted at the two-tailed 5% level. The statistical package StatView 5.0 (Stat Soft Inc., 2000) was used.

Results

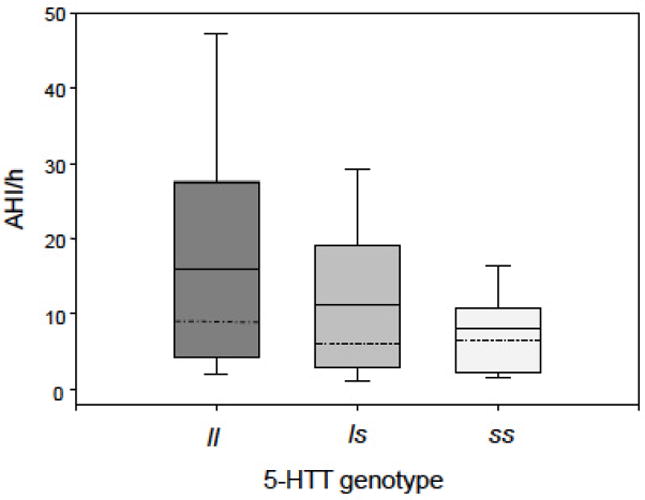

Table 1 displays the effect of 5-HTTLPR on the demographics of our study population. We did not observe any differences with respect to 5-HTTLPR genotype for gender and education. However, the l allele was found to be associated with increased age (p=0.043; Table 1). Observed 5-HTT s and l allele frequencies were 0.473 and 0.527, respectively, which is concordant with frequencies observed in other Caucasian samples (38). Genotypes did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (Chi-square = 0.64, p= 0.42). Regression analysis revealed a significant association of 5-HTTLPR with AHI (p=0.019) (Table 2, Figure 1). A single allele change in 5-HTTLPR genotype from s to l (i.e. from ss to ls or from ls to ll) resulted in an age-adjusted increase of AHI by 4.46 per hour of sleep (95%CI, 0.75-8.17). The l allele was also associated with longer time during sleep spent at oxygen saturation levels below 90% (p=0.014) with a single allele change corresponding to an increase of 11.26 minutes (95% CI, 2.35-20.18). Regression analysis displayed significant results independent of the inclusion or exclusion of age as a potential confounding factor in the analyses.

Table 1.

5-HTTLPR genotype distribution and mean values (standard deviations) for demographics by 5-HTTLPR allele group.

| 5-HTT ll n=28 |

5-HTT ls n=43 |

5-HTT ss n=23 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 73.25 (8.0) | 71.91 (7.9) | 68.74 (6.7) | .04 |

| Gender | 16w (57.1%) | 25w (58.1%) | 13w (56.5%) | .99 |

| Education | 16.92 (3.3) | 16.44 (2.2) | 15.83 (2.6) | .15 |

Abbreviations: 5-HTT, serotonin transporter; l, long allele; s, short allele; w, women

Table 2.

5-HTTLPR genotype distribution and mean values (standard deviations) for Obstructive Sleep Apnea, other sleep parameters and general characteristics by 5-HTTLPR allele group; Regression analysis controlling for age

| 5-HTT ll n=28 |

5-HTT ls n=43 |

5-HTT ss n=23 |

p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSG derived variables | |||||

| AHI | 16.11 (16.3) | 11.21 (12.2) | 8.09 (10.2) | .019 | .75 -8.17 |

| SaO2<90% (min) | 24.39 (42.6) | 15.16 (30.8) | 3.57 (6.5) | .014 | 2.35 - 20.18 |

| TST | 331.29 (82.6) | 335.44 (67.9) | 355. 11 (70.7) | .17 | -35.1 - 6.26 |

| REMS % TST | 13.9 (6.7) | 13.62 (6.2) | 15.12 (5.2) | .95 | -1.58 - 1.69 |

| Stage 1% TST | 16.65 (10.5) | 19.83 (9.8) | 16.75 (5.9) | .61 | -3.31 – 1.96 |

| Stage 2 %TST | 68.45 (10.9) | 64.37 (10.8) | 66.9 (5.4) | .69 | -2.26 - 3.36 |

| Stage 3 %TST | 1.25 (2.5) | 1.34 (2.9) | 0.78 (1.8) | .36 | - .39 - 1.07 |

| Stage 4% TST | 0.13 (0.5) | 0.85 (2.8) | 0.46 (1.5) | .73 | -.69 - .49 |

| WASO | 92.54 (69.3) | 110.06 (62.8) | 86.26 (55.3) | .97 | -18.37 - 17.76 |

| PLMS | 15.51 (17.9) | 14.34 (18.2) | 9.94 (14.5) | .46 | -3.05 - 6.69 |

| Self-report sleep variables | |||||

| ESS | 7.29 (4.3) | 7.30 (3.1) | 6.13 (4.2) | .37 | -.59 -1.56 |

| PSQI | 6.18 (3.4) | 7.12 (3.7) | 7.39 (4.2) | .31 | -1.62 -.52 |

| Body Mass Index | |||||

| BMI | 27.16 (3.8) | 27.63 (6.2) | 26.48 (3.5) | .37 | -.77 -2.02 |

Abbreviations: 5-HTT, serotonin transporter; l, long allele; s, short allele; PSG, Polysomnography; AHI, Apnea-Hypopnea Index; SaO2, Oxygen Saturation; TST, Total Sleep Time; REMS, Rapid Eye Movement Sleep; WASO, Wake After Sleep Onset; PLMS, Periodic Limb Movements During Sleep; ESS, Epworth Sleepiness Scale; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; BMI, Body Mass Index

Figure 1.

Main effect of 5-HTTLPR genotype on Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI). The l allele is significantly associated with AHI (p=0.019). A single allele change in 5-HTTLPR genotype from s to l results in an increase of AHI by 4.46 per hour of sleep (95% CI, 0.75-8.17). Boxes: 25th and 75th percentiles; bars: 10th and 90th percentiles; dashed line: median; continuous line: mean. Abbreviations: 5-HTT, serotonin transporter gene; s, short allele; l, long allele.

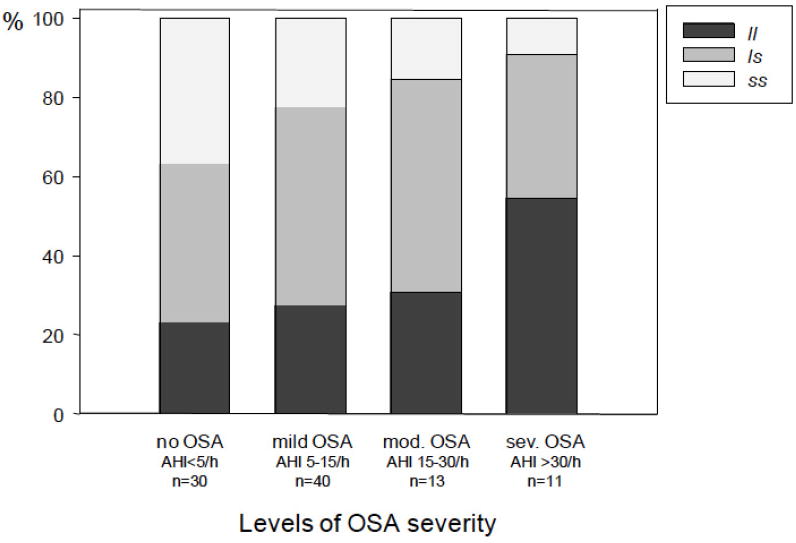

We did not observe any associations of genotype with total sleep time (TST), sleep architecture, wake-after-sleep-onset (WASO), or PLMS (see Table 2). Neither the self-report measure of daytime sleepiness (ESS) nor the level of self-report sleep quality as assessed with PSQI differed according to 5-HTT genotype. The Body Mass Index (BMI) in our sample was within the non-obese weight range and similar for the three genotypes (Table 2). No subject fulfilled the criteria for DSM IV-TR diagnosis of depression: the mean score on the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was 5.2±4.7, and GDS scores did not differ among the genotypes (data not shown). In order to gain a sense of clinical significance we also compared the genotype and allele frequency groups with respect to clinically relevant levels of OSA severity, employing the most commonly used cut-offs points for defining sleep related breathing disorders (32): AHI of <5 per hour of sleep indicates no OSA, AHI between 5-15 per hour of sleep indicates mild OSA, AHI between 15-30 per hour of sleep indicates moderate OSA and AHI >30/h indicates severe OSA. Significant differences were found in allele frequency distribution between participants who did not have OSA (AHI <5/h, l frequency 43.3%) compared to those with moderate (AHI 15-30/h, l frequency 57.7%; Chi-square = 4.83, p=0.027) and severe OSA (AHI >30/h, l frequency 72.7%; Chi-square = 5.57, p=0.018; see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

5-HTTLPR genotype distribution for different levels of OSA severity.

Older adults without OSA demonstrate significantly lower l allele frequenciescompared to those with moderate (Chi-square= 4.83, p=0.027) and severe OSA (Chisquare=5.5.7, p= 0.018). Abbreviations: 5-HTT, serotonin transporter gene; s, short allele; l, long allele; AHI, Apnea-Hypopnea Index.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates a significant association between the 5-HTTLPR l allele and AHI in community-dwelling older adults, and suggests an important relationship between the l allele of the 5-HTT gene and OSA severity in older Caucasian adults. Indeed, older l allele carriers displayed higher AHI and spent more time at oxygen saturation levels below 90% compared to s allele carriers. We found that the mere presence of a single l allele resulted in an age-adjusted increase of AHI by 4.46 per hour of sleep, which is striking, considering that the convention is to classify OSA as present when the AHI is >5. Also, l allele carriers exhibited dangerous ranges of respiratory events; of those participants with severe OSA (defined by AHI levels >30 events per hour of sleep), all but one were l allele carriers. In contrast, out of 23 s homozygote participants, 20 displayed either no OSA (AHI <5/hour) or OSA within the mild range (AHI 5-15/h) (see Figure 2). Similarly, the ranges for time spent below 90% of oxygen saturation, are significantly increased in l carriers (0-197 minutes in l carriers compared to 0-28 minutes in ss). If confirmed in future studies, these results may provide an important tool for identifying individuals at increased risk for developing OSA with age, especially for those prone to severe OSA.

Additionally, given that the percentage of ss subjects decreases at a similar rate from one severity category to the next, while the most marked increase in the percentage of lls occurs for the most severe range of OSA, it may not simply be that the l allele is associated with increased levels of OSA, but that the s allele may serve to protect against severe levels of OSA.

The current findings stand in contrast to the two previous studies that have investigated the association between 5-HTT genotype and OSA, albeit on different ethnicities. Ylmaz et al. (30) did not observe significant overall differences between 5-HTT genotype and allele frequencies in 27 OSA patients compared to 162 controls in a Turkish study population. However, the authors demonstrated a significantly increased l allele frequency in their male OSA patients (n=20) compared to female patients (n=7), as well as in male patients compared to male controls. Although this latter observation is in accordance with our own finding of an association of the l allele with OSA, we did not observe any gender effects. As a consequence of a restricted sample size in their patient group, the Ylmaz study may have been underpowered to detect any genotype or allele frequency differences between patients and controls. Or, it may be that age mediates the relationship of the l allele to AHI. Our population of older adults had a mean age of 72 (+- 8), in comparison, the cohort in Yue et al. had a mean age of 45.2 yrs for the patients, and in the Ylmaz cohort, the age of the patients were not stated, making comparisons difficult (28, 30).

Further, the 5-HTT promoter allele distribution varies widely by ethnicity (for review see (29)) which may limit the extent to which this investigation is comparable with our study. For example, it is interesting to note that African-Americans who are documented to have an increased prevalence of the l allele (39, 40), also have a significantly increased risk for severe OSA (41, 42). This issue must also to be kept in mind when comparing our results with those of Yue et al. (28) and Yilmaz et al (30), whose work on the serotonin transporter was performed on Chinese and Turkish participants, respectively. Other candidate genes may be involved in the development of OSA; a recent meta-analysis did not include an evaluation of the serotonin transporter, but did find one gene (TNFA rs1800629) that had a significant association with OSA. Finally, neither investigation considered the relationship of 5-HTT to AHI assessing the full spectrum of apnea levels (28, 30). We emphasize that our findings do not suggest an increased prevalence of OSA in individuals with the 5HTTLPR l allele, but rather that the l allele is associated with greater severity of OSA in older adults.

Previous studies demonstrated that the 5-HTT s allele interacts with stress to negatively impact depression (43-45), though not all studies supported this perspective (46). Additionally, the s allele has recently been suggested to moderate subjective sleep quality, as assessed by PSQI, in response to chronic stress (47). In the present investigation, we excluded ongoing major depression from participation in this study (as per structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR during the screening visit), and our older adult population displayed only very mild levels of depressive symptomatology (GDS 5.2±4.7). Similarly, the majority of participants did not express significant sleep complaints as assessed by PSQI (see Table 2). Finally, we did not observe any main effect of 5-HTTLPR on either depressive symptomatology (GDS) or subjective sleep quality (PSQI; see Table 2), even after controlling for AHI. Thus it is unlikely that either depression or associated sleep disturbances represented a significant source of bias for our main findings. Lack of any significant difference across the three genotype groups with respect to performance on the PSQI may have reflected the fact that we did not measure stress nor include it in our model.

Additionally, there was no difference across the three genotype groups with respect to the ESS which is typically elevated in individuals with OSA. Previous investigations of the 5HTTLPR have observed better cognitive performance in individuals with the l allele (36), suggesting that l allele carriers may have higher levels of AHI but are perhaps protected from, or can more easily compensate for the cognitive and fatigue symptoms that commonly accompany this disorder. As such l carriers may be less likely to experience the symptoms of OSA and thus are less likely to present for treatment of sleep problems, despite a higher severity of OSA.

Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with OSA, the search for effective treatments for OSA is of significance. Currently available treatments include mainly continuous or bilevel positive airway pressure (CPAP/BiPAP) as the gold standard treatment, weight loss, as well as mandibular advancement devices and upper airway surgical procedures, but there is still no readily available pharmacotherapy for OSA. Because of its implication in respiratory stability of the upper airways, the serotonergic system has been identified as one of the prime targets for pharmacological interventions for OSA. Further, studies suggest that presence of the s allele is associated with increased serotonin in the synapse. However, it cannot be concluded that SSRIs mimic presence of an s allele. The animal and human literature on the mechanism of the s allele suggests that it results in impaired transcriptional efficiency and more dysregulation of the serotonergic system rather than simply increased serotonin in the synapse (48, 49). However, some initial studies suggest SSRIs be an effective treatment for OSA. Prior to CPAP, tricyclic antidepressants were standardly utilized for the treatment of OSA, though limited by their side effect profile (50, 51). With the availability of SSRIs, the concept was revisited. One study compared protriptiline (a TCA) to fluoxetine (an SSRI), and found both medications caused a similar decrease in AHI NREM sleep, but could not compare reduction in REM due to significant decrease in REM time with fluoxetine (51). Subsequent investigations found similar results (52), which led investigators to add a 5HT3 antagonist which in combination reduced AHI about 40%, but did not improve subjective symptoms (53). Thus, findings to date on the impact of SSRIs on OSA are mixed (54). Indeed, the incomplete improvement in this investigation, as well as the mixed findings overall in studies of SSRIs for OSA, may in fact be attributable to the genetic effect that we describe in the current work.

Our results suggest that 5-HTT genotype may explain some of the observed variability among serotonergic pharmacological treatment studies for OSA. In other 5-HT related pathologies, 5-HTT genotype has been found to impact treatment response to SSRIs, e.g. in depression (55, 56) and generalized anxiety disorder (57) though studies have yielded mixed findings (58). Future studies employing serotonergic agents for OSA should consider assessment of 5-HTT genotype in order to identify patient subgroups that are responsive to serotonergic pharmacological treatment.

It is unclear how the 5-HTT l allele may affect OSA. Recent studies have contributed evidence that 5-HTT genotype has a functional impact on 5-HT availability also in the in vivo brain, although findings are mixed. Oquendo et al. did not observe any association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and brain 5-HT binding potential (23). In contrast, David et al. observed differential postsynaptic 5-HT receptor availability depending on 5-HTT genotype (26). Hu et al recently demonstrated a functional single nucleotide variant within l, (59) designated l(a) and l(g), which further influences 5-HTT expression, with l(a) being associated with high levels of in vitro 5-HTT expression, whereas l(g) is low expressing similar to s. Based on these findings, Reimold et al. (60) demonstrated increased 5-HTT binding potential in midbrain structures (including the raphe area, the center of origin of cortical and subcortical serotonergic projections) in l(a)/l(a) allele carriers. These studies are compatible with the notion that the l allele is associated with increased transcriptional efficiency, higher serotonin reuptake and more 5-HTT binding in the in vivo brain, which may result in lower 5-HT concentrations in extracellular space in the respiratory center and upper airways. The diminished serotonergic availability during sleep, suggested to contribute to the observed state-dependent upper airway collapse in OSA (17, 18) may thus be further reduced in l allele carriers. Increased age itself may be another factor exacerbating any reduced serotonergic availability. (19)

There are several limitations that constrain the interpretations that can be drawn from our study. Participation may have been subject to differential self-selection, as this investigation was advertised as a study on sleep and behavioral outcomes and subjects with poor sleep may have been over-represented. However, prevalence and severity of OSA in our study is comparable to other sleep studies investigating community-dwelling older adults with similar methodology. (1) Similarly, presence of sleep disorders other than OSA could have potentially biased the study population. However, Periodic Limb Movements during Sleep (PLMS) were observed at expected levels in this elderly population (M 13.48 ± 17.2) (61), and did not differ significantly between the 5-HTTLPR genotypes (see Table 2). Also, participants did not express manifest insomnia complaints, and PSQI values were similar for the three genotypes (see Table 2). Factors such as medication, age and gender were controlled for, and no impact was observed on our findings. However, there are additional factors which can impact sleep where we did not have information, such as caffeine use, stress during the day or level of physical activity, which should be considered in future investigations as potential moderators of the relationship of 5HTTLPR genotype to AHI severity.

Exclusion of participants who were already treated for OSA may have resulted in a selection bias if the excluded subjects preferentially carried the s allele. However, the distribution of alleles in our investigation is not substantially different from that in other investigations of this issue, nor in our own previous investigations of 5-HTT and behavioral outcomes. (36) Participants on serotonergic medication could have biased our study results. However, as older adults with ongoing major depressive episode were excluded from our study, only 4 out of the 94 study participants were on stable doses of serotonergic medication, including sertraline, paroxetine, duloxetine, escitalopram. Two were ll homozygous and two ls heterozygous. Exclusion of these subjects from the analyses did not change our main findings.

Furthermore, presence of the lg variant among the l/s genotype group may also influence the association between the l allele and OSA. Although we did genotype for lg, numbers were insufficient for comparison purposes. Specifically, we had only 4 subjects with the la/lg variant, with a mean AHI of 15.00, compared to 15.44 for the 27 subjects with the la/la variant. We had only 5 subjects with the lg/sa variant with a mean AHI of 13.2, and 40 subjects with the la/sa with a mean AHI of 11.93. However, these sample sizes are too small to make any conclusions regarding the potential of the lg variant to impact OSA or our own findings. Also, we did not assess the 5-HTT-VNTR polymorphism of the 5-HTT allele, which has been previously observed to be associated with OSA. (28) Finally, all of our study participants were Caucasians, restricting generalizability of our results to a non-Caucasian population, and the cross-sectional study design limits the conclusions we can infer regarding a mechanistic relationship between 5-HTT and OSA.

In conclusion, the current study finds the 5-HTT l allele to be a marker of OSA severity in older Caucasian adults. The observed association between the l allele and AHI in this age group may assist in identifying individuals at increased risk for developing OSA. Larger longitudinal genetic studies are required to assess the mechanistic relationship between serotonin and OSA, in particular regarding the 5-HTT l allele and OSA in older adults of different ethnic origin. Finally, these findings may explain some of the observed variability among serotonergic pharmacological treatment studies for OSA; 5-HTT genotype status may be taken into account in future therapeutic trials involving serotonergic agents.

Key Points.

This work is the first report of a positive association of the long allele variant of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) with higher levels of AHI in older adults. We believe that these findings are of high scientific importance and interest to the clinical and research community as the observed association may not only point to an important tool for individuals at increased risk for developing Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA); our findings also emphasize serotonergic involvement in obstructive sleep apnea in the elderly, and may explain some of the observed variability among serotonergic pharmacological treatment studies for OSA that should be taken into account in future therapeutic trials involving serotonergic agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health grants MH 070886, AG 18784 and AG 17824; by the State of California Department of Health Services (06-55310); by the Stanford/VA Alzheimers Disease Research Center of California; and by the Department of Veteran Affairs Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC).

References

- 1.Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O. Sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14:486–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, Redline S, Newman AB, Gottlieb DJ, Walsleben JA, Finn L, Enright P, Samet JM. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Int Med. 2002;162:893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gami AS, Somers VK. Obstructive sleep apnoea, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:709–711. 3. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ip MS, Lam B, Ng MM, Lam WK, Tsang KW, Lam KS. Obstructive sleep apnea is independently associated with insulin resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:670–676. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.5.2103001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorajja D, Gami AS, Somers VK, Behrenbeck TR, Garcia-Touchard A, Lopez-Jimenez F. Independent association between obstructive sleep apnea and subclinical coronary artery disease. Chest. 2008;133:927–933. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Hara R, Schroder CM, Kraemer HC, Kryla N, Cao C, Miller E, Schatzberg AF, Yesavage JA, Murphy GM., Jr Nocturnal sleep apnea/hypopnea is associated with lower memory performance in APOE epsilon4 carriers. Neurology. 2005;65:642–644. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173055.75950.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guilleminault C, Partinen M, Hollman K, Powell N, Stoohs R. Familial aggregates in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest. 1995;107:1545–1551. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.6.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer LJ, Buxbaum SG, Larkin E, Patel SR, Elston RC, Tishler PV, Redline S. A whole-genome scan for obstructive sleep apnea and obesity. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:340–350. doi: 10.1086/346064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pillar G, Lavie P. Assessment of the role of inheritance in sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:688–691. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redline S, Tosteson T, Tishler PV, Carskadon MA, Millman RP. Studies in the genetics of obstructive sleep apnea. Familial aggregation of symptoms associated with sleep-related breathing disturbances. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:440–444. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varvarigou V, Dahabreh IJ, Malhotra A, Kales SN. A review of genetic association studies of obstructive sleep apnea: Field synopsis and meta-analysis. SLEEP. 2011;34(11):1461–68. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayliss DA, Viana F, Talley EM, Berger AJ. Neuromodulation of hypoglossal motoneurons: Cellular and developmental mechanisms. Respir Physiol. 1997;110:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(97)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kubin L, Tojima H, Davies RO, Pack AI. Serotonergic excitatory drive to hypoglossal motoneurons in the decerebrate cat. Neurosci Lett. 1992;139:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90563-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood S, Morrison JL, Liu H, Horner RL. Role of endogenous serotonin in modulating genioglossus muscle activity in awake and sleeping rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1338–1347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-258OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morin D, Monteau R, Hilaire G. Compared effects of serotonin on cervical and hypoglossal inspiratory activities: An in vitro study in the newborn rat. J Physiol. 1992;451:605–629. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose D, Khater-Boidin J, Toussaint P, Duron B. Central effects of 5-ht on respiratory and hypoglossal activities in the adult cat. Respir Physiol. 1995;101:59–69. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(95)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakano H, Magalang UJ, Lee SD, Krasney JA, Farkas GA. Serotonergic modulation of ventilation and upper airway stability in obese zucker rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1191–1197. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2004230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veasey SC, Panckeri KA, Hoffman EA, Pack AI, Hendricks JC. The effects of serotonin antagonists in an animal model of sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:776–786. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behan M, Brownfield MS. Age-related changes in serotonin in the hypoglossal nucleus of rat: Implications for sleep-disordered breathing. Neurosci Lett. 1999;267:133–136. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heils A, Teufel A, Petri S, Stober G, Riederer P, Bengel D, Lesch KP. Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996;66:2621–2624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesch KP, Gutknecht L. Pharmacogenetics of the serotonin transporter. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1062–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, Huang YY, Simpson N, Arcement J, Huang Y, Ogden RT, Van Heertum RL, Arango V, et al. Lower serotonin transporter binding potential in the human brain during major depressive episodes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:52–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oquendo MA, Hastings RS, Huang YY, Simpson N, Ogden RT, Hu XZ, Goldman D, Arango V, Van Heertum RL, Mann JJ, et al. Brain serotonin transporter binding in depressed patients with bipolar disorder using positron emission tomography. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shioe K, Ichimiya T, Suhara T, Takano A, Sudo Y, Yasuno F, Hirano M, Shinohara M, Kagami M, Okubo Y, et al. No association between genotype of the promoter region of serotonin transporter gene and serotonin transporter binding in human brain measured by PET. Synapse. 2003;48:184–188. doi: 10.1002/syn.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Dyck CH, Malison RT, Staley JK, Jacobsen LK, Seibyl JP, Laruelle M, Baldwin RM, Innis RB, Gelernter J. Central serotonin transporter availability measured with [123i]beta-cit SPECT in relation to serotonin transporter genotype. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:525–531. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David SP, Murthy NV, Rabiner EA, Munafo MR, Johnstone EC, Jacob R, Walton RT, Grasby PM. A functional genetic variation of the serotonin (5-HT) transporter affects 5-HT1a receptor binding in humans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2586–2590. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3769-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinz A, Jones DW, Mazzanti C, Goldman D, Ragan P, Hommer D, Linnoila M, Weinberger DR. A relationship between serotonin transporter genotype and in vivo protein expression and alcohol neurotoxicity. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:643–649. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yue W, Liu H, Zhang J, Zhang X, Wang X, Liu T, Liu P, Hao W. Association study of serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in Chinese Han population. SLEEP. 2008;31(11):1535–41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.11.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelernter J, Cubells JF, Kidd JR, Pakstis AJ, Kidd KK. Population studies of polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter protein gene. Am J Med Genet. 1999;88:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ylmaz M, Bayazit YA, Ciftci TU, Erdal ME, Urhan M, Kokturk O, Kemaloglu YK, Inal E. Association of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:832–836. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000157334.88700.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology: Techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles: UCLA Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: Recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine task force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman RM, Bliwise DL, Sajben N, Boomkamp A, de Bruyn LM, Dement WC. Daytime sleepiness in patients with periodic movements in sleep. Sleep. 1982;5(Suppl 2):S191–202. doi: 10.1093/sleep/5.s2.s191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Iindex: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Hara R, Schroder CM, Mahadevan R, Schatzberg AF, Lindley S, Fox S, Weiner M, Kraemer HC, Noda A, Lin X, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphism, memory and hippocampal volume in the elderly: Association and interaction with cortisol. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:544–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu S, Brody CL, Fisher C, Gunzerath L, Nelson ML, Sabol SZ, Sirota LA, Marcus SE, Greenberg BD, Murphy DL, Hamer DH. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene and neuroticism in cigarette smoking behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:181–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho HJ, Meira-Lima I, Cordeiro Q, Michelon L, Sham P, Vallada H, Collier DA. Population-based and family-based studies on the serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms and bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:771–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gelernter J, Kranzler H, Coccaro EF, Siever LJ, New AS. Serotonin transporter protein gene polymorphism and personality measures in African American and European American subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1332–1338. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.10.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weese-Mayer DE, Berry-Kravis EM, Maher BS, Silvestri JM, Curran ME, Marazita ML. Sudden infant death syndrome: Association with a promoter polymorphism of the serotonin transporter gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;117A:268–274. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Stepnowsky C, Estline E, Chinn A, Fell R. Sleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1946–1949. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, Tosteson TD, Strohl KP, Spry K. Racial differences in sleep-disordered breathing in African-Americans and Caucasians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:186–192. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-htt gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs N, Kenis G, Peeters F, Derom C, Vlietinck R, van Os J. Stress-related negative affectivity and genetically altered serotonin transporter function: Evidence of synergism in shaping risk of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:989–996. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Vittum J, Prescott CA, Riley B. The interaction of stressful life events and a serotonin transporter polymorphism in the prediction of episodes of major depression: A replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:529–535. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillespie NA, Whitfield JB, Williams B, Heath AC, Martin NG. The relationship between stressful life events, the serotonin transporter (5-httlpr) genotype and major depression. Psychol Med. 2005;35:101–111. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brummett BH, Krystal AD, Ashley-Koch A, Kuhn CM, Zuchner S, Siegler IC, Barefoot JC, Ballard EL, Gwyther LP, Williams RB. Sleep quality varies as a function of 5-HTTLPR genotype and stress. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:621–624. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31814b8de6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parsey RV, Hastings RS, Oquendo MA, Huang YY, Simpson N, Arcement J, et al. Lower serotonin transporter binding potential in the human brain during major depressive episodes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:52–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathews TA, Fedele DE, Coppelli FM, Avila AM, Murphy DL, Andrews AM. Gener dose-dependent alterations in extraneuronal serotonin but not dopamine in mice with reduced serotonin transporter expression. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;140:169–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guilleminault C, Eldridge FL, Tilkian A, Simons B, Dement WC. Sleep apnea syndrome due to upper airway obstruction. Arch Int Med. 1977;137:296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanzel DA, Proia NG, Hudgel DW. Response of obstructive sleep apnea to fluoxetine and protryptiline. Chest. 1991;100:416–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.2.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraiczi H, Hedner J, Dahloff P, Ejnell H, Carlson J. Effect of serotonin inhibition on breathing during sleep and daytime symptoms in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1999;22:61–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prasad B, Radulovacki M, Olopade C, Herdegen JJ, Logan T, Carley DW. Prospective trial of efficacy and safety of ondansetron and fluoxetine in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. SLEEP. 2010;33:982–989. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Veasey SC. Serotonin agonists and antagonists in obstructive sleep apnea: Therapeutic potential. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:21–29. doi: 10.1007/BF03256636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serretti A, Benedetti F, Zanardi R, Smeraldi E. The influence of serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism (sertpr) and other polymorphisms of the serotonin pathway on the efficacy of antidepressant treatments. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:1074–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lorenzi C, Pirovano A, Olgiati P, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Serotonin transporter gene influences the time course of improvement of “core” depressive and somatic anxiety symptoms during treatment with ssris for recurrent mood disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stein MB, Seedat S, Gelernter J. Serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism predicts ssri response in generalized social anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;187:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kraft JB, Peters EJ, Slager SL, Jenkins GD, Reinalda MS, McGrath PJ, Hamilton SP. Analysis of association between the serotonin transporter and antidepressant response in a large clinical sample. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:734–742. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, Xu K, Arnold PD, Richter MA, Kennedy JL, et al. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:815–826. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reimold M, Smolka MN, Schumann G, Zimmer A, Wrase J, Mann K, Hu XZ, Goldman D, Reischl G, Solbach C, et al. Midbrain serotonin transporter binding potential measured with [11c]dasb is affected by serotonin transporter genotype. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:635–639. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Mason WJ, Fell R, Kaplan O. Periodic limb movements in sleep in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14:496–500. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]