Abstract

Response habituation is a fundamental form of nonassociative learning, yet there are substantial individual differences in its electrodermal manifestation. We employed a latent class analysis to identify discrete groups of electrodermal responders to a series of loud tones. We also evaluated whether heterogeneity in responsiveness was associated with lifetime prevalence of externalizing psychopathology and major depression. Participants were community-recruited men (N = 1141) who underwent a standard habituation paradigm. A latent class analysis resulted in the identification of four electrodermal populations: rapid habituators, habituators, and two classes that showed weak response habituation, but differed markedly in their amplitude profiles. Relative to rapid habituators, members of slower habituating classes were less likely to receive lifetime diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder and substance dependence. Further research using this analytical strategy could help identify the functional significance of individual differences in habituation.

Keywords: electrodermal, habituation, psychopathology, substance dependence, depression

A chain of neurological responses, including orienting reflexes, occur when the central nervous system attends to novel or meaningful stimuli in its environment. The corollary of orienting reactivity is habituation, in which the orienting response diminishes with repeated exposure to an innocuous stimulus. In electrodermal habituation paradigms, participants typically respond to the leading tone(s) in a stimulus series, eventually showing extinction of the skin conductance orienting response. However, there are substantial individual differences in the rate of habituation as well as various qualitative patterns of responding. Some participants may fail to respond altogether, while others may never cease responding to the stimulus series (nonhabituation).

The psychiatric significance of individual differences in habituation is ambiguous (Bernstein et al., 1988). Although the psychophysiological literature is replete with descriptions of “abnormalities” in electrodermal habituation, there are few benchmarks for determining whether certain patterns of habituation are more or less adaptive. For example, electrodermal non-responding is often cited as indicative of abnormalities in schizophrenia (Bernstein et al., 1982; Dawson, Nuechterlein, & Schell, 1992), but its opposite manifestation – electrodermal nonhabituation – is also reported at elevated rates in some groups of schizophrenics (Bernstein, 1987; Gruzelier & Venables, 1972). While these findings may be useful for understanding specific subtypes within a particular disorder such as schizophrenia, they do not contribute to a general theory about the nature of individual differences in the elicitation and extinction of the orienting response.

Personality correlates of habituation in normal samples have typically been elusive (Koriat, Averill, & Malmstrom, 1973). According to a review by O’Gorman (1977), there is mixed support for the idea that extraversion may be associated with faster habituation, but the theoretical premise for such a relationship is questionable. The relationship between personality variables and electrodermal habituation has received scant attention over the past quarter-century. More recently, Crider (2008) has argued that electrodermal response lability – a phenomenon encompassing resistance to habituation - is a marker for individual differences in effortful self-control. As such, resistance to habituation should correlate (inversely) with levels of antisocial behavior and other externalizing problems.

The lack of clear-cut associations between response habituation and personality variables may stem from difficulties in operationalizing the construct of habituation. O’Gorman (1977) outlined five different methods that investigators have used to measure habituation: trials-to-criterion indices, regression indices, frequency indices, mean response amplitude, and amplitude difference scores. At present, the two prevailing measures are trials-to-criterion (i.e., number of trials elapsing until response failure) and the linear regression of response magnitude on log trial number (Dawson, Schell, & Filion, 2007). However, their validities are questionable given that these two measures are not highly correlated, and have often led to different results within the same study (Graham, 1973; Smith & Wigglesworth, 1978; Smith, Concannon, Campbell, Bozman, & Kline, 1990).

Improvements in methods that can be used to measure habituation are necessary to better illuminate the significance of individual differences in this fundamental process. In particular, there may be limits to how well we can understand response habituation if the only methods used to investigate it assume it is best considered a dimensional phenomenon in which individuals differ by degree. Electrodermal responsiveness may also be profitably viewed as qualitatively differing across individuals, where participants can be grouped into discrete classes based on their pattern of responsivity to repeated sensory presentation.

Present Study

Given the lack of consensus on quantifying habituation, we adopted an innovative categorical approach to characterize this process in a large sample of community-recruited participants. We also examined the construct validity of this approach using external clinical criteria. In a previous report (Isen, Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2012), we found that electrodermal responsiveness to nonsignal stimuli was inversely associated with externalizing psychopathology in adolescent twins. However, we did not focus on any particular psychiatric diagnosis, as the sample had not passed through the age of risk for many externalizing disorders (e.g., antisocial personality disorder and alcohol dependence). Moreover, we were unable to determine whether reduced responsiveness is specific to the externalizing spectrum, as we did not assess any forms of internalizing psychopathology. Major depression would have been particularly relevant to examine due to its moderate incidence and the fact that previous studies indicate that individuals with affective disorders show a general retardation in electrodermal responsivity (Iacono et al., 1984; Iacono, Ficken, & Beiser, 1999; Thorell, Kjellman, & d’Elia, 1987).

In the present study, a latent class analysis was performed on participants’ responses in order to empirically differentiate groups with respect to their pattern of responding. This permitted us to evaluate whether there are groups of hyper-responders and nonresponders in a general population sample, as well as whether other groups characterized by varying rates of habituation may be present. This analytical strategy is based on mixture modeling, where the data effectively “speak for themselves” in order to capture unobserved heterogeneity in electrodermal responding. Finally, we examined the degree to which any emerging classes had clinical significance by determining how they differed in terms of lifetime prevalence for major depressive disorder and various externalizing disorders.

Method

Participants

All participants were fathers of twins from the Minnesota Twin Family Study (see Iacono & McGue, 2002). There were two age groups of twins: a “younger” cohort recruited at age 11 and an “older” cohort recruited at age 17. Fathers underwent a comprehensive psychophysiological assessment during the family’s intake visit. They were tested in the years 1990–1998. A total of 1196 participants underwent a standard habituation paradigm, including 530 “older cohort” fathers and 666 “younger cohort” fathers. Most individuals were in middle adulthood (M = 43.7 years, SD = 5.9) and of European-American extraction. Full demographic details of this sample are reported by Holdcraft and Iacono (2002).

Procedure

Participants listened to a series of 17 tones through headphones while comfortably seated in front of a screen. They were asked to focus their attention on a closed-captioned movie clip and to ignore the meaningless tones. The first 15 tones, as well as the 17th tone, were presented at a frequency of 1000 Hz. However, the tone on the 16th trial was presented at a lower pitch (600 Hz). The purpose of this tone was to measure the extent of re-orienting and to trigger dishabituation (as reflected by the SCR to the 17th tone). All stimuli had rise and fall times of 20 ms, and durations of 500 ms. Due to a change in laboratory equipment that took place on May 5, 1995, early participants were tested at 101.5 dB, and those seen after this date were assessed at 105 dB. Interstimulus intervals varied in length from 45 to 75 s (mean = 60 s).

Skin conductance was recorded on both hands using pairs of Ag-AgCl electrodes. A solution of 0.5 molar NaCl electrolyte and Unibase cream served as the conducting medium. Each pair of bipolar electrodes was attached to the distal phalanges of the second and fourth digits. [For 21 participants (1.8%), the intended finger sites were missing or otherwise damaged. In such instances, we used alternate digit pairs, typically involving the third digit.] A constant voltage of 0.5 V was passed between electrodes, and the output signal was recorded through DC amps on a Grass Model 12A Neurodata acquisition system. The data were sampled at 256 Hz, and filtered with a 3 Hz low-pass filter.

SCR Scoring Criteria

The digitized skin conductance signal was scored by a computer algorithm in order to obtain two parameters for each trial: response peak and latency. According to our algorithm, a response peak was detected when the slope of the signal changed from positive to negative. If a peak was detected, then a preceding latency was marked at the inflection point where the slope became positive. These markings were visually inspected on the raw waveforms to ensure the absence of atypical responses or non-physiological artifacts, and were adjusted accordingly. Skin conductance response (SCR) magnitude was defined as the difference in microsiemens (µS) between response peak and latency point, and was averaged across both hands.

The presence or absence of a response on each trial was used to characterize each participant’s habituation response profile. In order for a response to be valid, the magnitude needed to exceed .01 µS and the latency needed to occur within 1–4 seconds of stimulus onset. Trials that did not fulfill these criteria were judged non-responses, and scored as zero. Conditional on the presence of a non-zero response, we also utilized the SCR amplitude.

Fifty-five individuals (4.6%) had invalid data because they fell asleep during the task, had severe hearing loss, or took anticholinergic medication. This reduced the sample size to 1141 individuals. A small minority of remaining participants (n = 20) lacked some data points due to recording and task administration errors. However, since information was not missing for all trials, these individuals could be retained in the latent class analysis.

Psychopathology Assessment

Clinical disorders were assessed using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-III-Revised (American Psychiatric Association, 1987). Two or more graduate students in clinical psychology reviewed diagnostic interview data during case conferences, and assigned symptoms by consensus. We were interested in lifetime prevalence for five types of disorders: antisocial personality, nicotine dependence, alcohol dependence, drug dependence, and major depression. Since the diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is dependent on meeting criteria for childhood conduct disorder, we also relaxed the latter requirement in order to assess the presence of adult antisocial behavior (i.e., four adult onset Criterion C ASPD symptoms were required). Only one-half (49.6%) of individuals who exhibited clinical features of adult antisocial behavior also showed a history of conduct disorder.

Substance-related information was assessed through the Substance Abuse Module of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Robins, Baber, & Cottler, 1987). A diagnosis of drug dependence was determined with respect to eight substances: amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, phencyclidine, and sedatives. The vast majority (79.3%) of individuals who received lifetime diagnoses of drug dependence were dependent on cannabis. For each diagnosis, data were available for at least 98.5% of participants. Inter-rater reliability (kappa) coefficients exceeded 0.89 for all diagnoses (Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999).

Analytic Plan

A unique challenge in conceptualizing habituation is that the SCR magnitudes associated with each trial are effectively censored-inflated variables. That is, a strong floor effect renders SCR magnitudes semi-continuously rather than continuously distributed. Values are censored from below due to the practice of recoding SCR magnitudes to zero if falling below a certain threshold. More importantly, there is an inflation of zero values stemming from the fact that many participants will inevitably fail to respond to a given stimulus.

This implies a need to differentiate between the presence/absence of responding and the size (amplitude) of a response. Reliance on crude SCR magnitude in habituation paradigms has usually been a matter of necessity arising from the fact that conventional statistical tests (e.g., repeated measures ANOVA) cannot handle the “missingness” associated with amplitude data (Venables & Mitchell, 1996). That is, exclusion of non-responses is precluded by the issue of missing data and the consequent listwise deletion of participants. Recent developments in full-information maximum likelihood techniques afford us the opportunity to disentangle the continuous amplitude information from the binary response component of SCR magnitudes.

We conducted a “two-part” latent class analysis of electrodermal responses, in which SCR magnitudes were modeled separately as binary response information and amplitude data (Olsen & Schafer, 2001). First, the SCR magnitude for each trial was used to construct a binary response variable. Contingent on a response, the SCR magnitude was square-root transformed to create a continuous (amplitude) variable. In the event of non-responses, values for the continuous variable were treated as missing. In sum, the original set of 17 magnitudes was used to construct 34 new outcome measures.

Latent class analyses with 17 binary indicators and 17 continuous indicators were conducted in Mplus Version 6 (Muthen & Muthen, 2010) using maximum likelihood estimation. By default, Mplus uses a sandwich estimator to allow for the computation of nonnormal (robust) standard errors. We allowed amplitude variances to differ across class. As a result, we estimated a total of 51 parameters in each class. When exploring various class solutions (i.e., selecting the optimal number of latent classes), we did not jointly include clinical covariates in our analyses, as this would have been too computationally intensive. Rather, we first established a stable solution for each class model by replicating the best log-likelihood, and then incorporated diagnostic variables into our final model. The latent classes were regressed on each diagnostic variable using a multinomial logistic regression procedure. In Mplus, the outcome variable (class membership) is weighted by the posterior probabilities of belonging to each class. The resultant regression coefficient represents the log odds ratio that individuals with a clinical diagnosis belong to a given class versus a reference class (weighted by their posterior probabilities). For ease of interpretation, we converted log odds ratios into odds ratios.

The optimal number of classes was selected on the basis of the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001). The p-value yielded by this test determines whether one can reject the null hypothesis that a neighboring class model (with one fewer class) is viable. We first examined whether a model with two latent classes is superior to one where no classes are present. We then progressively tested the fit of less reduced models (i.e., where one more class was added). This process was continued until the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood test for a given model was nonsignificant (p > .05). We also reported the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), in which lower values indicate a better fitting model.

Due to the large sample size, we sought to validate our latent class solution by replicating it in random split halves of our sample. We assigned participants to two groups in SPSS Version 20 (Armonk, NY) by randomly selecting exactly half of the 1196 cases in our dataset. Unselected cases were used to create the 2nd half. Ultimately, the two halves represented 571 and 570 participants, respectively, with valid electrodermal data.

Results

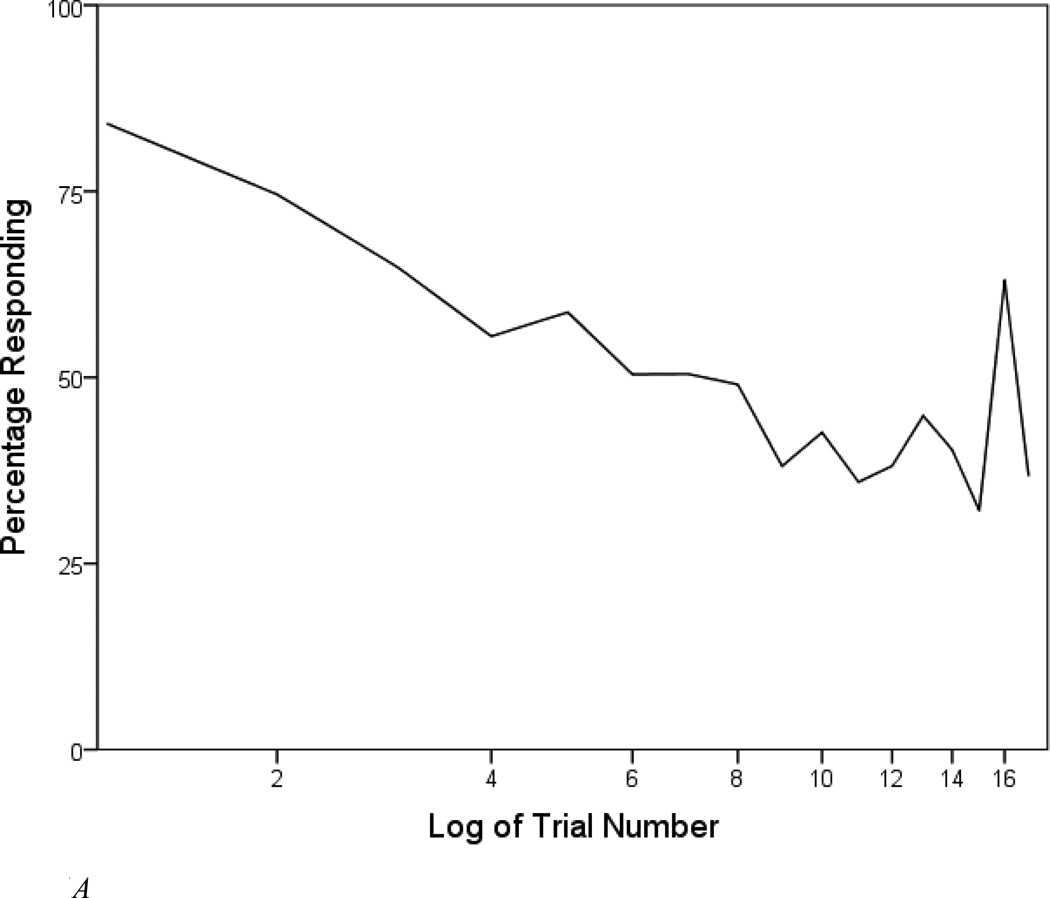

The rate of responding across the 17 tones is plotted in Figure 1A. Over 80% of participants responded to the first tone. Responsiveness steadily decreased over the course of trials 1–4, after which responding hovered around the 50% rate. It is apparent that re-orienting took place on trial 16 (novel pitch), as the rate of responding increased to 63%. However, habituation was not interrupted on trial 17, as the proportion of responders (36.7%) was only modestly higher than for the 15th tone (32.1%). That is, there was little evidence for dishabituation.

Figure 1.

A. Percentage of participants responding to each tone in the habituation series. Tones were presented at 1000 Hz for all trials except Trial 16 (600 Hz).

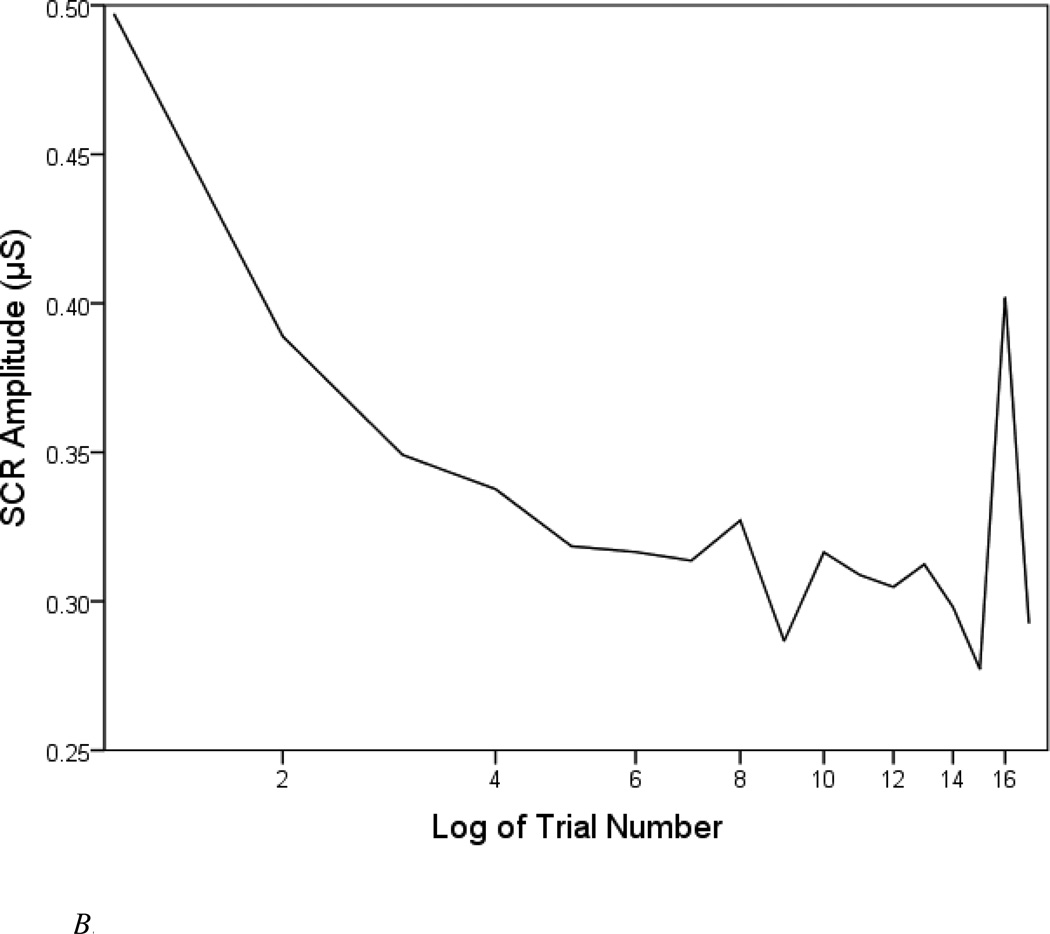

B. Square-root of mean SCR amplitude.

The pattern of SCR amplitudes mirrored that of the binary response rate, as can be seen in Figure 1B. Most participants are represented in this graph, as all but 83 individuals (92.7%) responded to one or more tones. Amplitudes decreased most dramatically between Trial 1 and Trial 2. Again, reactivity strongly increased on Trial 16, and dishabituation was not apparent.

We next investigated the optimal number of classes. Relative fit of the various models are reported in Table 1 for the random split halves. Due to the sheer number of continuous parameters, the BIC never reached a minimum, but rather progressively decreased as the number of classes increased. We thus relied on the outcome of the Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) likelihood ratio test to inform our model selection.

Table 1.

Model Selection Criteria

| 1st Random Split Half | 2nd Random Split Half | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | BIC | LRT p-value |

Model | BIC | LRT p-value |

| 1-class | 10657 | 1-class | 10542 | ||

| 2-class | 6255 | < .01 | 2-class | 6424 | <.01 |

| 3-class | 4938 | < .01 | 3-class | 4952 | <.01 |

| 4-class | 4293 | .01 | 4-class | 4477 | .04 |

| 5-class | 4179 | .52 | 5-class | 4334 | .32 |

Notes. BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion. LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; p-values represent the viability of a neighboring (null) model with one fewer class.

A model with two latent classes was superior to a null model in which there was no heterogeneity in the patterning of responses. This was demonstrated by the fact that the LMR likelihood ratio test was significant (p < .01), indicating that a one-class solution is untenable. Similar results were obtained when comparing the three-class and four-class models to neighboring models (ps < .05). However, a five-class model was not preferred over a four-class model, as demonstrated by a non-significant outcome of the LMR test (p > .32).

The four-class structure that emerged in the split halves was similar to that in the full sample. A breakdown of the different classes, based on most likely class membership, is listed in Table 2. We report relevant summary statistics - namely, the total number of responses and mean SCR amplitude across the stimulus series. A small minority of participants (Class 1 “nonhabituators”) responded across most trials and exhibited very large SCR amplitudes. The remaining three classes contained an approximately equal proportion (30%) of participants. The second class responded nearly as frequently as nonhabituators, but showed much smaller SCR amplitudes. Members of the third and fourth classes followed a trend of progressively diminishing response frequency and mean SCR amplitude.

Table 2.

Sample Sizes and Mean Profile of the Four Latent Classes

| Class | N (proportion) | Number of Responses |

Mean SCR Amplitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Split Half | |||

| 1 | 79 (13.8%) | 14.1 ± 3.1 | 0.59 ± 0.11 |

| 2 | 154 (27.0%) | 13.2 ± 2.5 | 0.37 ± 0.06 |

| 3 | 168 (29.4%) | 8.7 ± 2.9 | 0.26 ± 0.07 |

| 4 | 170 (29.8%) | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 0.23 ± 0.10 |

| 2nd Split Half | |||

| 1 | 45 (7.9%) | 14.9 ± 2.0 | 0.64 ± 0.13 |

| 2 | 159 (27.9%) | 13.1 ± 2.7 | 0.40 ± 0.06 |

| 3 | 188 (33.0%) | 9.3 ± 3.2 | 0.29 ± 0.08 |

| 4 | 178 (31.2%) | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 0.21 ± 0.08 |

| Full Sample | |||

| 1 | 138 (12.1%) | 14.3 ± 2.8 | 0.60 ± 0.12 |

| 2 | 328 (28.7%) | 13.0 ± 2.7 | 0.37 ± 0.06 |

| 3 | 343 (30.1%) | 8.6 ± 3.0 | 0.27 ± 0.08 |

| 4 | 332 (29.1%) | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.21 ± 0.08 |

Notes. Values placed after the plus-minus signs are standard deviations. Mean SCR amplitude is measured in microsiemens (µS), and is square-root transformed.

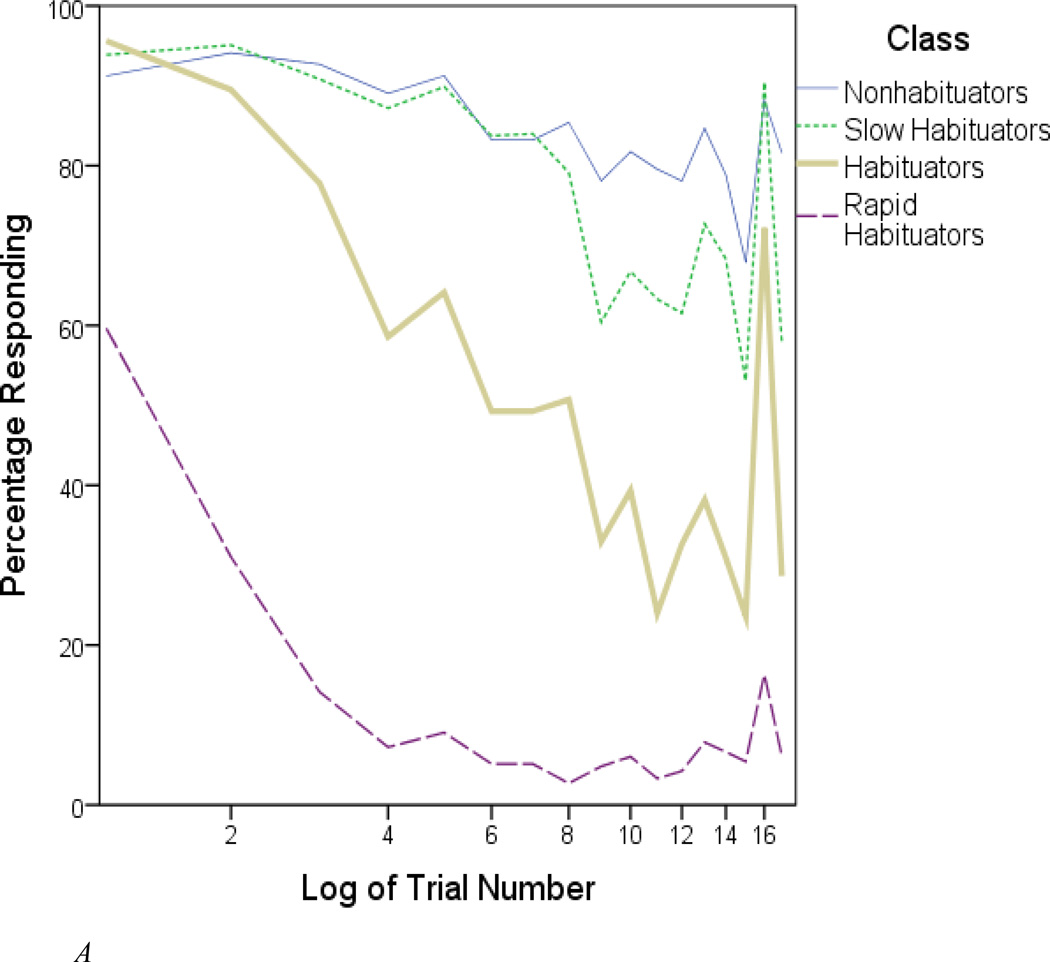

The probability of responding to a given trial is plotted in Figure 2A for each of the four classes. (Data are only shown for the full sample, as response patterns closely mirrored those of the split halves.) Two of these classes seemed easy to interpret on the basis of their binary response information. One class could be described as comprising “habituators”. Members of this class universally responded to the first tone, and showed a gradual decrease in responsiveness over subsequent trials. Most members re-oriented to the 16th (novel pitch) tone. Another class showed even faster habituation. Its members (whom we label “rapid habituators”) exhibited few responses after reacting to the initial tone. Less than 20% responded to the re-orienting tone. This class included a minority of non-responders, but it should be emphasized that the frequency of non-responding was low in our sample (7.3%). In fact, we did not identify a distinct group of non-responders even when peering into the five-class solution.

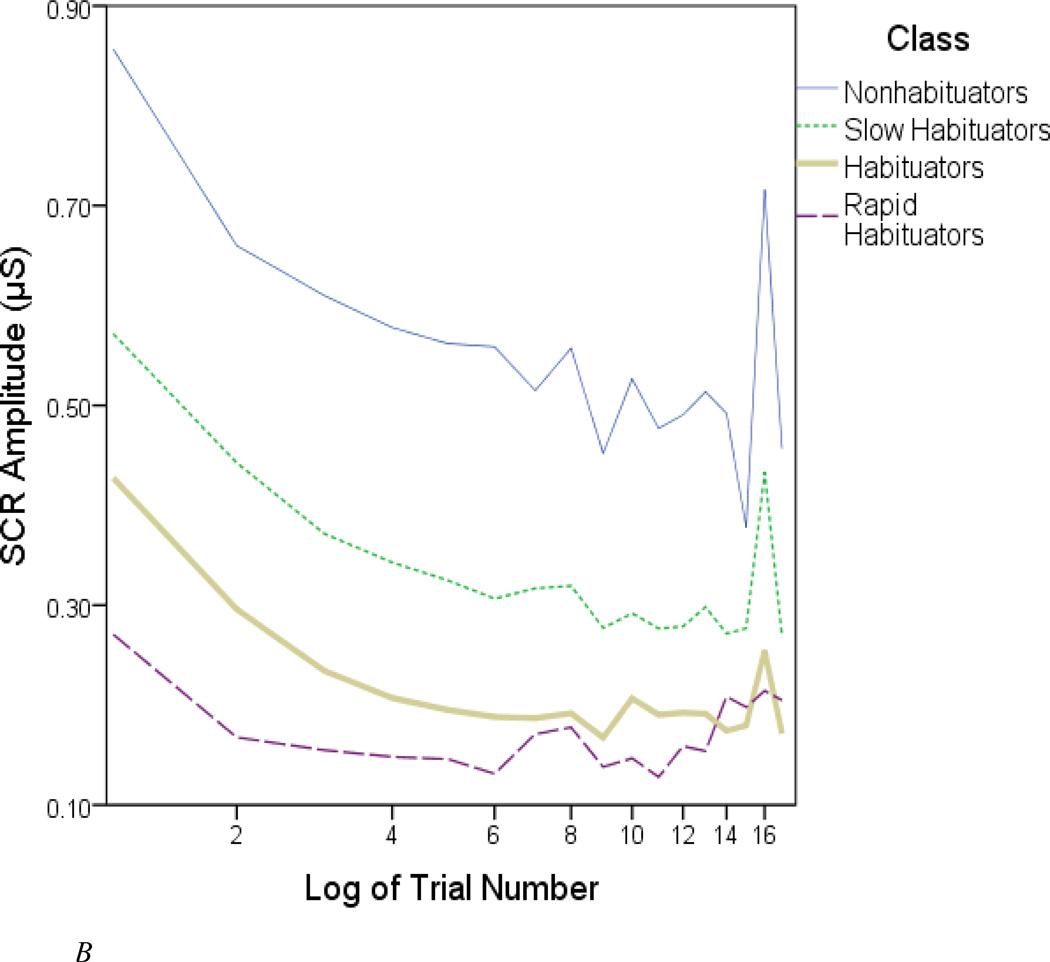

Figure 2.

A. Percentage responding within each latent class. Participants were classified on the basis of most likely class membership.

B. Square-root of mean SCR amplitude.

Nonhabituators tended to respond to all trials; the probability of responding to a given trial never dipped below two-thirds. The remaining class (“slow habituators”) showed a similarly high rate of responsiveness during the 1st half of the paradigm, but slackened somewhat after Trial 8. It was necessary to examine their amplitude information in order to clearly distinguish these two groups (see Figure 2B). In general, classes that habituated faster had lower amplitudes. For example, nonhabituators produced pervasively high SCR amplitudes, while rapid habituators produced weak amplitudes on the few trials to which they responded.1

Clinical Significance

Next, we compared how the four latent classes differed with respect to lifetime prevalence of various externalizing disorders and major depressive disorder. The percentage of class members who received a given diagnosis is listed in Table 3. There was a clear pattern for rapid habituators to exhibit the most psychopathology. As a result, we reported the multinomial logistic regression results using rapid habituators as our reference group. Odds ratios represent the odds of belonging to each comparison class, given that one has a diagnosis. Since individuals can be fractionally assigned to different classes, the regression of class membership on diagnosis is weighted by each individual’s posterior probability.

Table 3.

Lifetime Prevalence of Externalizing Disorders and Major Depressive Disorder

| Disorder | Nonhabituators | Slow Habituators |

Habituators | Rapid Habituators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASPD | 4.2% 0.45 [0.18, 1.15] |

2.8% 0.30 [0.14, 0.66] |

3.7% 0.39 [0.19, 0.81] |

8.9% |

| Adult ASB | 8.4% 0.51 [0.26, 1.01] |

5.0%a 0.29 [0.16, 0.54] |

9.7% 0.59 [0.34, 1.04] |

15.3% |

| Nicotine Dependence |

32.7%a 0.37 [0.24, 0.58] |

35.9% 0.43 [0.31, 0.61] |

43.8% 0.60 [0.42, 0.85] |

56.5% |

| Alcohol Dependence |

30.9% 0.60 [0.35, 1.04] |

28.8% 0.54 [0.38, 0.78] |

34.9% 0.72 [0.50, 1.03] |

42.6% |

| Drug Dependence | 12.2% 0.81 [0.45, 1.47] |

8.9% 0.57 [0.35, 0.92] |

9.2% 0.59 [0.37, 0.96] |

14.6% |

| Any Drug/Alcohol Dependence |

33.7% 0.60 [0.39, 0.92] |

32.4% 0.56 [0.40, 0.79] |

37.4% 0.70 [0.50, 0.98] |

46.0% |

| Major Depression | 9.5% 0.53 [0.28, 1.04] |

12.2% 0.71 [0.44, 1.14] |

16.1% 0.98 [0.63, 1.54] |

16.4% |

Notes. Odds ratios are listed below the prevalence rates, and correspond to the odds of receiving a diagnosis as compared to rapid habituators; 95% confidence intervals are enclosed in brackets. Adult ASB refers to meeting the adult criteria for ASPD.

Prevalence is significantly lower relative to habituators, p < .05

For most externalizing disorders, there was a trend for slow habituators to possess lower prevalence rates than habituators, who in turn manifested lower prevalence relative to rapid habituators. Habituators and slow habituators were significantly less likely than rapid habituators to receive lifetime diagnoses of ASPD, nicotine dependence, and drug dependence. Nonhabituators evinced a similar pattern of lower externalizing psychopathology, although they significantly differed from rapid habituators only with respect to nicotine dependence. When we combined all intoxicating substances (i.e., drugs and alcohol) into a single dependence category, significant differences emerged between rapid habituators and all other groups. There were no instances in which nonhabituators and slow habituators differed from one another. When compared to habituators, however, nonhabituators had lower lifetime prevalence of nicotine dependence (p < .05), and slow habituators had lower prevalence of adult ASB (p < .05).

One could argue that our drug-related diagnoses are overly broad, given that diverse drugs (e.g., amphetamines and sedatives) exert very different effects on the sympathetic nervous system. In practice, cannabis was the only drug category for which a nontrivial number of participants received positive diagnoses. We did not detect any significant differences across class with respect to cannabis dependence (data not shown). Finally, classes could not be differentiated with respect to major depressive disorder.2

We also examined whether electrodermal non-responders differed clinically-wise from their fellow “responders” within the rapid habituation class. Although a distinct class of non-responders did not emerge, previous research has often emphasized non-responders as fundamentally different from responders (Dawson et al., 2007). It is possible that the higher externalizing psychopathology observed in rapid habituators was driven disproportionately by the presence of electrodermal non-responders. Eighty-three individuals failed to respond to a single stimulus during the 17-trial habituation paradigm. After excluding these individuals, the lifetime prevalence of ASPD, nicotine dependence, and alcohol dependence was 9.7%, 56.6%, and 43.9%, respectively. As can be seen in Table 3, these proportions are slightly higher than those found among the overall population of rapid habituators. Thus, electrodermal non-responders do not present a more clinically deviant picture as compared to rapidly habituating responders.

A final concern is that the various classes might not represent different patterns of habituation per se, but rather reflect differences in level (e.g., intercept) as much as change with repeated stimulation. For example, it is apparent that rapid habituators exhibited smaller amplitudes to the initial stimulus relative to members of other classes. As a result, it is unclear if the elevated psychopathology observed in this group stems from their unique pattern of habituation or is a by-product of initial differences in response rate/amplitude. To shed light on this question, we added the Trial 1 SCR magnitude (square-root transformed) as a covariate when performing the multinomial logistic regression of class on each clinical diagnosis. We conducted this regression analysis in a post-hoc manner by using individuals’ most likely class membership as the dependent variable. Diagnoses of nicotine dependence continued to predict class membership (i.e., successfully distinguished rapid habituators from each of the three other classes) after controlling for initial SCR magnitude, ps < .02. Moreover, rapid habituators continued to exhibit higher rates of alcohol dependence and adult ASB (but not ASPD) relative to slow habituators. This instills confidence in our interpretation that rates of psychopathology can be tied to differences in how responses unfold (i.e., habituation) rather than simply stemming from differences in intercept.

Discussion

Individual differences in habituation of the skin conductance orienting response have typically been examined in clinical populations that already manifest severe psychopathology. In particular, abnormal patterns of habituation have been observed in schizophrenia and severely depressed patients (Bernstein et al., 1982; Iacono et al., 1999). The present study, by contrast, sought to characterize individual differences in habituation in a community-recruited sample of men. These individuals were administered a standard habituation paradigm using loud tones (in excess of 100 dB), as employed in previous investigations (Isen et al., 2012; Lykken, Iacono, Haroian, McGue, & Bouchard, 1988).

Habituation is usually conceived as a quantitatively measureable phenomenon – a “rate” of how quickly one adapts to repeated sensory stimulation. One of the most common measures is the number of stimulus repetitions required for the SCR to disappear, known as trials-to-criterion. This approach relies on dichotomous response data, and ignores information pertaining to the size (amplitude) of responses. Another common measure is the linear regression of response magnitude on the logarithm of trial number. This method does not make any qualitative differentiation between the presence/absence of responding and its conditional amplitude; i.e., the binary and continuous elements are conflated.

We used a two-part approach to identify common patterns of electrodermal responding. That is, we modeled both the binary and continuous components of response magnitudes. Unlike other procedures, we made no explicit attempt to calculate rates of habituation. Using a latent class modeling approach, we inferred four qualitatively distinct groups of electrodermal responders: nonhabituators, slow habituators, habituators, and rapid habituators.

Two classes comprised individuals who demonstrated a clear pattern of habituation, i.e., only a minority of class members continued responding to trials after a certain point. This point was reached very early by rapid habituators. This class is similar to the “fast habituator” group identified by Patterson & Venables (1978), in which subjects produced one or two responses before habituation. In the case of habituators, the rate of responding decreased much more steadily. Most members responded to both the initial tone and a subsequent novel pitch. Additionally, we identified two classes where habituation was weak or inconspicuous. Response amplitude profiles best served to distinguish these groups. One class was labeled “nonhabituators”, as the rate of responding was persistently high and response amplitudes were exaggeratedly large.

The latent classes differed with respect to lifetime prevalence of several externalizing disorders. Rapid habituators were particularly deviant, as they consistently were more likely to receive lifetime diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder and substance dependence relative to slower habituating groups. Prevalence of major depression did not significantly differ across the various latent classes. This provides initial support for the idea that electrodermal responsiveness is more intimately linked to the externalizing than internalizing spectrum of psychopathology. A similar inference can be gleaned from Jandl, Steyer, and Kaschka (2010), who observed that violently suicidal patients with depression habituated faster to a tone sequence than did non-suicidal patients. In other words, it is the externalizing tendency to inflict physical harm rather than negative emotionality per se that is related to faster habituation.

The broader literature indicates that antisocial personality features (i.e., conduct disorder and psychopathy) are related to lower electrodermal activity on habituation tasks (Lorber, 2004). The present report extends these findings by demonstrating that less deviant externalizing characteristics such as (licit) substance misuse are also associated with an electrodermally hyporeactive profile. This suggests that rule-breaking and outwardly antagonistic aspects of externalizing behavior are not crucial components of this phenomenon. Rather, features as common as nicotine dependence appear to be prominently associated with individual differences in habituation. Further research should address whether electrodermal hyporeactivity is a consequence of the cumulative effects of nicotine and ethanol exposure on nervous system functioning, or is instead a risk factor for these negative health outcomes (vis-à-vis genetic vulnerability to low self-control). Prospective studies of children are especially well suited to ascertain the direction of causality.

A potentially interesting result is that slow habituation was weakly associated with illicit drug dependence and, more specifically, unrelated to cannabis dependence. This might reflect the downstream psychological consequences of cannabis misuse. For example, nicotine and cannabis exert contrasting effects on cognition, especially in the area of working memory (Viveros, Marco, & File, 2006). If a history of cannabis misuse interferes with short-term memory processes, then it might also lead to poorer neural efficiency in non-associative learning tasks (e.g., habituation). That is, individuals with memory deficits should exhibit less efficient attenuation of the orienting response, in line with Öhman’s (1979) perspective that an orienting response is generated when an incoming stimulus fails to match the stored neural representation of preceding stimuli. Indeed, an uncharacteristically large proportion (24%) of nonhabituators received lifetime diagnoses of cannabis abuse. This leads to the possibility that drug-induced impairments are perhaps masking the fast habituation profile inherent to the externalizing spectrum.

Slow habituators and nonhabituators varied considerably in their profile of amplitudes, but did not differ clinically. This implies that individual differences in response amplitude are not clinically informative, certainly not above and beyond frequency/rate of responding. Evidence suggests that the size of the skin conductance orienting response is less psychologically meaningful than frequency-based measures of responding (see Raine & Venables, 1984). Indeed, in a previous investigation focusing on the children of the present participants, we reported that externalizing liability was more strongly associated with response frequency than with mean SCR amplitude (Isen et al., 2012).

Naturally, members of the different classes differed sharply in the total number of responses they produced. The fact that habituators were intermediate between slow habituators and rapid habituators with respect to “number of responses” as well as prevalence of several externalizing disorders suggests that response frequency may be a suitable proxy for resistance to habituation. Similar to the latent class modeling approach, response frequency circumvents the problem of quantifying an explicit rate, and provides a more complete picture of participants’ responses than a trials-to-criterion index (Coles, Gale, & Klein, 1971).

Nearly one-half of participants failed to conspicuously habituate to the stimuli. Given that habituation to repetitive sensory stimulation is considered an adaptive process (Lykken et al., 1988), it may seem ironic that those who resisted habituation were less clinically deviant than those who habituated more efficiently. However, it is important to note that response habituation is dependent on the specific stimulus conditions. In the present paradigm, the stimuli were intense and the intertrial intervals were rather long (> 45 s). This could explain why a large proportion of participants were slow habituators.

We did not identify an electrodermal nonresponding class. Again, this may arise from the fact that our stimuli were intense. Other studies have reported a higher rate of nonresponding in non-clinical samples, but the tones have typically been presented at milder intensities (70–85 dB). For example, Venables and Mitchell (1996) observed a non-responding rate of 24.5% in a large, nationally representative sample of children and young adults. This proportion decreased to 9.1% when they used a series of six 90 dB tones instead of 75 dB tones.

Limitations and Future Directions

A major limitation is that the theoretical implications of individual differences in habituation are unclear. The stimulus properties and task conditions that shape orienting and response habituation have been thoroughly delineated (e.g., Siddle, 1991), but this level of analysis has generated few hypotheses regarding the nature of the underlying psychophysiological mechanisms governing these individual differences. Thus, it is difficult to offer a compelling theoretical rationale for why resistance to habituation should be associated with lower externalizing liability. We can only acknowledge that previous investigators have noted a robust association between externalizing problems and faster habituation to innocuous tones (e.g., Herpertz et al., 2001; Herpertz et al., 2003; Raine, Venables, & Williams, 1990).

Although admittedly speculative, it may be the case that faster habituation reflects greater boredom susceptibility or stimulation seeking. The salience of the tones may be lost on individuals who quickly adapt to novel stimulation in their environment. This could facilitate or reflect enhanced tolerance to alcohol and nicotine. Unfortunately, the association between sensation seeking and habituation rate is ambiguous, with some research suggesting that the two are unrelated (e.g., Neary & Zuckerman, 1976).

Another limitation is that we cannot ensure that the tones were considered innocuous by every participant. If individuals experienced the tones as aversive, this could have the effect of increasing their responsiveness to the stimuli. However, it would be difficult to explain why individuals with lower prevalence of externalizing disorders should find the tones more aversive. If anything, externalizing problems are related to greater negative emotionality, including enhanced stress reactivity (Krueger, 1999). Furthermore, our habituation findings may not generalize to samples that have experienced habituation paradigms at milder intensities. The particular latent classes that we identified may not necessarily emerge in other studies. For example, if less intense stimuli are employed, it would likely give rise to an identifiable group of non-responders.

It should also be recognized that the subgroups identified by latent class analysis should not be reified. That is, various classes of habituation may not exist in nature. Rather, the process of habituation may be adequately described by response frequency – a continuously (albeit non-normally) distributed variable in the population. Mixture modeling will tend to generate multiple categories even when the underlying input is continuous, i.e., only one group truly exists in the population (see Bauer & Curran, 2003). Nonetheless, we believe that latent class analysis is a convenient tool to classify individuals, especially as it avoids the arbitrariness of categorizing individuals on a rational basis (e.g., drawing a line between non-responders and habituators). Even if habituation is in fact a dimensional phenomenon, we maintain that latent class analysis is informative within the present field where the relevant psychophysiological literature has often emphasized the dichotomous and polychotomous nature of electrodermal responding.

A potentially fruitful endeavor may be to assimilate our knowledge of individual differences in habituation to electrodermal response lability theory. There is a large literature on the psychological correlates of two contrasting electrodermal populations: labiles and stabiles (Crider, 2008; Dawson et al., 2007). Research suggests that electrodermal stabiles - who show a reduced frequency of nonspecific responses - are characterized by inferior performance on tasks that require sustained vigilance. Frequency of nonspecific responses is strongly associated with a trials-to-criterion habituation measure (Crider et al., 2004), suggesting that electrodermal stabiles may largely coincide with rapid habituators. Thus, it is worthwhile to examine whether different habituation classes show different patterns of performance on laboratory tasks that require sustained cognitive effort. More importantly, the labile-stabile construct may be relevant to our understanding of externalizing psychopathology, as electrodermal lability is thought to index individual differences in the exercise of effortful self-control, including the regulation of antagonistic impulses (Crider, 2008).

We remain optimistic that understanding the nature of individual differences in habituation may help shed light on the nature of mental disorders. An important first step is to effectively characterize common response patterns. It may be advantageous to conceive habituation as a process that describes different populations, rather than quantifying it as a continuous rate. We conclude that a thorough examination of the psychological characteristics that discriminate between different classes of electrodermal responders is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse under award numbers R37DA005147 and R01DA024417. Additionally, the first author was supported by T32 grant MH017069 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

In a related vein, classes that showed greater resistance to habituation (according to Figure 2A) tended to show visibly steeper decrements in amplitude. This illustrates a chief limitation of the linear regression approach, in which a steeper (more negative) slope in SCR magnitude is supposedly indicative of faster habituation. This misrepresentation arises from the fact that the intercept and slope strongly covary, sometimes reaching correlation coefficients as great as r = −0.9 (Coles et al., 1971; Koriat et al., 1973; Lykken et al., 1988). Naturally, individuals with higher initial reactivity will typically have a steeper negative slope.

Given that the sound level of tones increased from 101.5 to 105 dB after May 5, 1995, we repeated our multinomial logistic procedure after including a dummy-coded epoch variable as a covariate. The effects for all diagnoses remained substantively similar.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: Implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychological Methods. 2003;8:338–363. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein AS. Orienting response research in schizophrenia: where we have come and where we might go. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13:623–641. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein AS, Frith CD, Gruzelier JH, Patterson T, Straube E, Venables PH, Zahn TP. An analysis of the skin conductance orienting response in samples of American, British, and German schizophrenics. Biological Psychology. 1982;14:155–211. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(82)90001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein AS, Riedel JA, Graae F, Seidman D, Steele H, Connolly J, Lubowsky J. Schizophrenia is associated with altered orienting activity; depression with electrodermal (cholinergic?) deficit and normal orienting response. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:3–12. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles MG, Gale A, Kline P. Personality and habituation of the orienting reaction: tonic and response measures of electrodermal activity. Psychophysiology. 1971;8:54–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1971.tb00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crider A. Personality and electrodermal response lability: An interpretation. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2008;33:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s10484-008-9057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crider A, Kremen WS, Xian H, Jacobson KC, Waterman B, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, Lyons MJ. Stability, consistency, and heritability of electrodermal response lability in middle-aged male twins. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:501–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson ME, Nuechterlein KH, Schell AM. Electrodermal anomalies in recent-onset schizophrenia: relationships to symptoms and prognosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1992;18:295–311. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson ME, Schell AM, Filion DL. The electrodermal system. In: Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, Berntson GG, editors. Handbook of Psychophysiology. 3rd edition. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- Graham FK. Habituation and dishabituation of responses innervated by the autonomic nervous system. In: Peeke HV, Herz MJ, editors. Habituation I: Behavioral Studies. New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 163–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gruzelier JH, Venables PH. Skin conductance orienting activity in a heterogeneous sample of schizophrenics. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1972;155:277–287. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz SC, Mueller B, Wenning B, Qunaibi M, Lichterfeld C, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Autonomic responses in boys with externalizing disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2003;110:1181–1195. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz SC, Wenning B, Mueller B, Qunaibi M, Sass H, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Psychophysiological responses in ADHD boys with and without conduct disorder: implications for adult antisocial behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1222–1230. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft LC, Iacono WG. Cohort effects on gender differences in alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2002;97:1025–1036. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Ficken JW, Beiser M. Electrodermal activation in first-episode psychotic patients and their first-degree relatives. Psychiatry Research. 1999;88:25–39. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Lykken DT, Haroian KP, Peloquin LJ, Valentine RH, Tuason VB. Electrodermal activity in euthymic patients with affective disorders: one-year retest stability and the effects of stimulus intensity and significance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1984;93:304–311. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, McGue M. Minnesota Twin Family Study. Twin Research. 2002;5:482–487. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isen JD, Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Examining electrodermal hyporeactivity as a marker of externalizing psychopathology: a twin study. Psychophysiology. 2012;49:1039–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandl M, Steyer J, Kaschka WP. Suicide risk markers in major depressive disorder: a study of electrodermal activity event-related potentials. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;123:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriat A, Averill JR, Malmstrom EJ. Individual differences in habituation: some methodological and conceptual issues. Journal of Research in Personality. 1973;7:88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. Personality traits in late adolescence predict mental disorders in early adulthood: a prospective-epidemiological study. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:39–65. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell N, Rubin D. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF. Psychophysiology of aggression, psychopathy, and conduct problems: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:531–552. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykken DT, Iacono WG, Haroian K, Mcgue M, Bouchard TJ. Habituation of the Skin-Conductance Response to Strong Stimuli - a Twin Study. Psychophysiology. 1988;25:4–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1988.tb00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus users guide. 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neary RS, Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking, trait, and state anxiety, and the electrodermal orienting response. Psychophysiology. 1976;13:205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1976.tb00098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gorman JG. Individual differences in habituation of human physiological responses: a review of theory, method, and findings in the study of personality correlates in non-clinical populations. Biological Psychology. 1977;5:257–318. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(77)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A. The orienting response, attention, and learning: An information-processing perspective. In: Kimmel HD, van EH, OlstOrlebeke JF, editors. The orienting reflex in humans. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1979. pp. 443–471. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen MK, Schafer JL. A Two-Part Random-Effects Model for Semicontinuous Longitudinal Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:730–745. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson T, Venables PH. Bilateral skin conductance and skin potential in schizophrenic and normal subjects: the identification of the fast habituator group of schizophrenics. Psychophysiology. 1978;15:556–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1978.tb03109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Venables PH. Electrodermal nonresponding, antisocial behavior, and schizoid tendencies in adolescents. Psychophysiology. 1984;21:424–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1984.tb00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Venables PH, Williams M. Autonomic orienting responses in 15-year-old male subjects and criminal behavior at age 24. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:933–937. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Baber T, Cottler LB. Composite International Diagnostic Interview: Expanded Substance Abuse Module. St. Louis, MO: Author [L.N.R.]; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Siddle DA. Orienting, habituation, and resource allocation: an associative analysis. Psychophysiology. 1991;28:245–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1991.tb02190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, Concannon M, Campbell S, Bozman A, Kline R. Regression and criterion measures of habituation - a comparative analysis in extroverts and introverts. Journal of Research in Personality. 1990;24:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, Wigglesworth MJ. Extraversion neuroticism in orienting reflex dishabituation. Journal of Research in Personality. 1978;12:284–296. [Google Scholar]

- Thorell LH, Kjellman BF, d'Elia G. Electrodermal activity in antidepressant medicated and unmedicated depressive patients and in matched healthy subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1987;76:684–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables PH, Mitchell DA. The effects of age, sex and time of testing on skin conductance activity. Biological Psychology. 1996;43:87–101. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(96)05183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viveros MP, Marco EM, File SE. Nicotine and cannabinoids: Parallels, contrasts and interactions. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30:1161–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]