Abstract

Purpose

Studies have linked low pH and loss of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) in the intervertebral discs (IVDs) of patients with discogenic back pain. The purpose of the present study is to determine whether the chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) effect of GAG (gagCEST) is pH-dependent and whether it can be used to detect pH changes in IVD specimens. Iopromide, a FDA approved agent for CT/X-Ray, was also evaluated as a pH-sensitive CEST probe to explore the agents’ potential to measure IVD pH.

Methods

The pH dependency of the CEST effect of chondroitin sulfate (containing GAG) and Iopromide phantoms was investigated at 7 T. Z-spectra from porcine IVD specimens were acquired before and after manipulating the pH with sodium lactate. Iopromide was injected into the specimens and the calibration curve was used to determine the pH status.

Results

Chondroitin sulfate showed a non-linear dependence of gagCEST effect with pH and gagCEST signal differences were detected in the specimens. The CEST effect of Iopromide resulted in a sigmoidal relation with pH and was used to measure pH.

Conclusion

gagCEST is sensitive to pH and enables investigation of the IVD pH status. Iopromide CEST is independent of the local GAG concentration and has the potential for measuring pH in the IVD.

Keywords: CEST, gagCEST, pH, chondroitin sulfate, Iopromide, intervertebral disc

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain is an expensive, widespread healthcare concern with an increasing financial impact on the society (1). Different studies have demonstrated a relationship between intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration and low back pain (2, 3). While the mechanisms of back pain progression and its association with intervertebral disc degeneration are not fully understood, recent studies suggest that lactate (Lac) accumulation and the subsequent drop in pH may be initiating events (4).

The IVD consists of distinct tissue components including the annulus fibrosis (AF), the outer cartilaginous ring that maintains the flexibility of the spinal column, and the nucleus pulposus (NP), a gelatinous core that prevents the AF from buckling under pressure an thus provides the resistive properties of the IVD. The NP is comprised largely of proteoglycans (PG), molecules with a protein core with multiple chains of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) covalently attached. The disc is highly avascular and thus nutrients must diffuse significant distances (up to 5 mm) from nearby, peripheral capillaries. The IVD cells rely on anaerobic glycolysis to generate energy and lactic acid is produced at high rates (3). When the IVD cells are metabolically taxed, Lac is accumulating and the pH of the disc drops. This has been shown to cause a number of metabolic changes to the cell of the IVD (5). Previous studies have linked low pH and loss of GAG in patients IVDs with discogenic back pain (6).

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) of GAG (gagCEST) (7) has emerged as way to quantify GAG concentrations in the intervertebral disc (8, 9). However no studies have examined the gagCEST dependency on pH. It has been shown that other CEST effects can be pH-dependent and can be used to calibrate microenvironment pH (10, 11, 12). For example, amide proton transfer imaging (APT), which is a CEST imaging technique focused on the detection of the amide protons, is capable of detecting pH and is therefore a noninvasive endogenous pH imaging technique (13, 14, 15). It was also previously found that glutamate, which is a major neurotransmitter in the brain, shows not only a concentration dependent, but also a pH-dependent CEST effect (GluCEST) (16). Based on the results of these studies, the gagCEST effect may be also sensitive to pH.

Various exogenous CEST contrast agents are also known to be sensitive to pH (17). One of these, Iopromide (known as Ultravist from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Berlin, Germany), is of special interest, because it is already FDA-approved for X-Ray/CT imaging. Chen and coworkers have shown that Iopromide has two amides that generate different pH-dependent CEST effects (18). The ratio of the CEST effect correlates with pH between 6.0 and 7.2 and is independent of the local agent concentration and T1 relaxation time. The feasibility of using Iopromide as an extracellular pH maker detectable through CEST imaging was successfully tested on phantoms and in vivo on mouse model of MDA-MB-231 mammary carcinoma (18).

The accumulation of Lac and a decrease in pH may be the initiating factor in disc degeneration and discogenic back pain (19). MRI methods to measure pH in IVD would therefore be valuable in research and clinical settings. In this study, we explored two different strategies to assess the pH value in porcine discs ex vivo. The first investigates the pH-dependence of gagCEST effect on chondroitin sulfate phantoms and evaluates if the gagCEST signal is changing when Na-Lac is injected into the porcine IVD for pH manipulation. In the second approach we investigated the use of Iopromide as an exogenous pH probe for IVD specimens. Phantoms at different pH containing Iopromide are used to calibrate the pH dependent CEST effect of Iopromide. The potential to measure pH of the IVD before and after Na-Lac injection using Iopromide and CEST imaging is then explored.

METHODS

Sample preparation

Chondroitin sulfate - and Iopromide phantoms

Chondroitin sulfate is a sulfated GAG and a component part of diarthrodial joints and IVDs. The substance was used in phantom experiments to study different aspects of the gagCEST effect (7, 8). Chondroitin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was diluted with H2O to a concentration of 200 mM and separated into twelve 5 mm diameter glass tubes. Samples were titrated with NaOH or HCl to obtain a range of pH values: 5.70, 6.00, 6.09, 6.34, 6.52, 6.91, 7.12, 7.20, 7.36, 7.55, 7.90 and 8.25. Iopromide (Ultravist® 370, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Berlin, Germany (1 mL contains 0.769 g of Iopromide)) was also diluted in H2O to a concentration of 200 mM, separated into seven 5 mm diameter glass tubes and titrated to a range of pH values: 5.96, 6.18, 6.40, 6.70, 6.88, 7.12, and 7.48. The pH of each individual sample was measured using a pH meter (Oakton ION 510 series, Vernon Hills, IL, USA).

Porcine IVD samples

Porcine lumbar spine samples of 2- to 5- month-old piglets were obtained from a U.S. Department of Agriculture-approved slaughterhouse (Baigio Artisan Meats, Oakland, CA, USA) 5-6 h after slaughter and were frozen at −80°C until used. After thawing, the soft tissue was removed. The samples were cut such that the discs were completely separated from the vertebral bone with all other anatomical regions of the disc in tact. Five IVDs underwent the baseline MR imaging protocol, then samples were taken out of the MRI scanner and injected with a 1 M Na-Lac solution (Sodium L-lactate, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and imaged again using the same MR acquisition parameters. IVDs were then dissected in order to estimate the pH of the NP. The pH of the IVD was measured using a tissue pH meter (Oakton ION 510 Series, Vernon Hills, IL, USA) as well as pH indicator paper (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

MRI measurements

All MRI experiments were performed on a 7 T (310 mm bore size) superconducting magnet equipped with actively shielded imaging gradients (400 mT/m maximum gradient strength, 120 mm inner bore size) (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). A 38 mm inner diameter quadrature 1H birdcage resonator (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used for RF pulse transmission and signal reception. The positions of the phantoms (and porcine IVD specimens) were checked with a localizer sequence (gradient echo acquisition, repetition time (TR) = 10 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.4 ms, field of view (FOV) = 80×80 mm2, matrix = 128×128, slice thickness = 1 mm, three orthogonal slices). Shimming was performed with a 3D field-mapping sequence provided by the manufactures’ VnmrJ 3.1 scanner software (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The following shimming method was used to optimize the B0-field homogeneity: Global shimming for the phantoms experiments and slice selective shimming in a 3 mm slice covering the complete NP of the IVD for the specimens scans. The chondroitin sulfate pH experiments were carried out with a heat pad wrapped around the phantoms and the temperature was adjusted to 37°C.

CEST imaging

CEST z-spectra were acquired using a pulsed CEST-preparation module with a single slice turbo spin echo (TSE) imaging scheme (for parameters see Table 1). Imaging was performed through the center of the IVD. Additionally one dataset was obtained where the RF-pulse power for the CEST preparation module was turned off (CESToff). This dataset set was acquired for normalization of the CEST signal (see Equation [1] in “Data Analysis”). Water saturation shift reference (WASSR) data was acquired with the similar imaging module (shorter TR) to correct the z-spectra for B0-inhomogeneities (for parameters see Table 1) (20).

Table 1.

Parameters for CEST and WASSR imaging.

| Phantom Chondroitin |

Phantom Iopromide |

Disc specimens gagCEST |

Disc specimens Iopromide |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEST | Pulse type | Gauss | Gauss | Gauss | Gauss |

| Number of pulses | 30 | 50 | 30 | 50 | |

| Inter-pulse delay [ms] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Saturation power [μT] | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| Pulse bandwidth [Hz] | 25 | 50 | 25 | 50 | |

| Pulse length [ms] | 108 | 54 | 108 | 54 | |

| Spectral bandwidth [kHz] | −3 to 3 | −3 to +3 | −1 to 1 | −3 to +3 | |

| Spectral resolution [Hz] | 25 | 50 | 25 | 50 | |

|

TSE

Imaging Module |

TR [ms] | 3500 | 3000 | 3500 | 3000 |

| TEeff [ms] | 49.0 | 35.5 | 50.3 | 50.3 | |

| TSE-Factor | 32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | |

| FOV [mm × mm] | 32 × 32 | 40 × 40 | 40 × 40 | 40 × 40 | |

| Matrix | 64 × 64 | 128 × 128 | 64 × 64 | 64 × 64 | |

| Resolution [mm × mm] | 0.5 × 0.5 | 0.31 × 0.31 | 0.63 × 0.63 | 0.63 × 0.63 | |

| Slice thickness [mm] | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Number of averages | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total time | 28min 14s | 48min 30s | 9min 27s | 12min 6s | |

| WASSR | Pulse type | Gauss | Gauss | Gauss | Gauss |

| Number of pulses | 10 | 16 | 10 | 10 | |

| Inter-pulse delay [ms] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Saturation power [μT] | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| Pulse bandwidth [Hz] | 25 | 50 | 25 | 50 | |

| Pulse length [ms] | 108 | 54 | 108 | 54 | |

| Spectral bandwidth [kHz] | −1 to 1 | −1 to +1 | −0.5 to 0.5 | −1 to 1 | |

| Spectral resolution [Hz] | 25 | 50 | 25 | 50 | |

|

TSE

Imaging Module |

TR [ms] | 3000 | 3000 | 1200 | 1200 |

| TEeff [ms] | 49.0 | 35.5 | 50.3 | 50.3 | |

| TSE-Factor | 32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | |

| FOV [mm × mm] | 32 × 32 | 40 × 40 | 40 × 40 | 40 × 40 | |

| Matrix | 64 × 64 | 128 × 128 | 64 × 64 | 64 × 63 | |

| Resolution [mm × mm] | 0.5 × 0.5 | 0.31 × 0.31 | 0.63 × 0.63 | 0.63 × 0.63 | |

| Slice thickness [mm] | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Number of averages | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Total time | 8min 12s | 16min 30s | 1min 38s | 1min 38s |

Lac imaging

Lac imaging was performed as a check to ensure that Lac was successfully incorporated into the IVD in order to manipulate the pH. The selective multiple quantum coherence editing sequence (Sel-MQC) filter combined with 2D chemical shift imaging scheme was used to detect the Lac signal amplitude in the IVD specimens before and after administration of the Na-Lac solution in the IVDs (21, 22). The Sel-MQC filter enables the suppression of co-resonant lipid signals and Lac signal detection in a single scan. The following parameters were used for the sequence: TR = 1 s, TE = 1/JLac = 144 ms, FOV = 40 × 40 mm2, matrix = 16 × 16, slice thickness = 3.8 mm, spectral bandwidth = 6 kHz, spectral points = 256, number of averages = 2, total time = 8 min 32 s.

Data analysis

CEST z-spectra analysis

The raw MR data was processed using Matlab (Matlab 2007a, Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). CEST processing was accomplished similar to the study by Kim et al. (20). The raw data was zero filled by a factor of two in the two spatial dimensions (image space), before Fast Fourier transformation. A mask was generated based on the background noise in the CEST images with the largest preparation offset in order to exclude noise data from the further analysis. On a pixel-by-pixel basis, the z-spectra and the WASSR-spectra were interpolated to 1 Hz spectral resolution using a spline filter. The WASSR-spectra were fitted to estimate the absolute water frequency offset in every pixel to correct the CEST z-spectra for B0-inhomogeneities (20). The CEST z-spectra were corrected for B0-inhomogeneities and the CEST asymmetry (MTRasym) plots were calculated by subtraction of the magnitude z-spectra signal at positive frequency offset from that at the negative frequency offset, divided by the signal from the non-saturated acquisition:

| [1] |

Chondroitin sulfate phantoms

The pH dependence of gagCEST was determined by analyzing the z-spectra of the chondroitin sulfate phantoms prepared with different pH. Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually drawn in each phantom and the mean ROI signal was calculated. MTRasym plots were created for each of the phantoms. The integral of the asymmetry curves from 50 Hz to 450 Hz (the frequency offset of the OH-groups in gagCEST (7)) and the percentage of MTRasym at 0.75 ppm (225 Hz) were calculated. The data was plotted against the known pH of the samples to obtain the gagCEST pH-dependency curves.

Iopromide phantoms

For calibration of the pH-dependence of the Iopromide, the amide group peaks at 4.2 ppm and 5.6 ppm were analyzed (see also (18)): The logarithmic ratio of the amplitude at 4.2 ppm (S(Δω)4.2ppm) divided by the peak amplitude at 5.6 ppm (S(Δω)5.6ppm) (normalized on CESToff) was plotted against the known pH of the different samples:

| [2] |

Porcine IVD measurements (Na-Lac application)

Five IVDs were imaged at baseline (Lac, CEST and WASSR imaging – parameters Table 1), then removed from the scanner, injected with a 1M Na-Lac solution and returned to the MRI machine for the follow-up MR experiments (with the same MR protocol as for the baseline scan). The Lac imaging was done pre- and post- Na-Lac injection to ensure that the solution was successfully incorporated into the IVDs. Special care was taken to ensure that the IVDs were positioned within the coil in the same configuration as at baseline.

Iopromide porcine IVD measurements

Iopromide (200 mM Iopromide solution) was injected into IVD to test the ability to report pH using the calibration data created from the Iopromide pH phantom measurements. Lac, CEST and WASSR imaging was performed (parameters see Table 1). After baseline scans the IVD was removed from the scanner, Na-Lac was injected into the NP and a follow up scan with the same MR-protocol was performed.

RESULTS

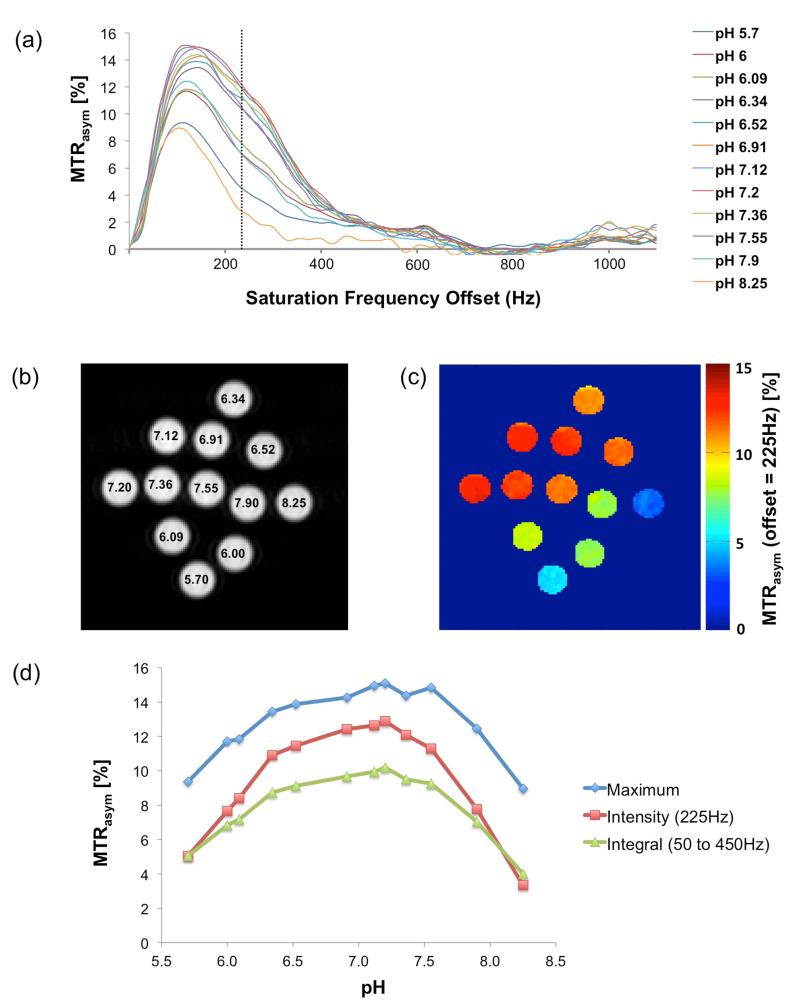

Fig. 1a shows the MTRasym plots of the twelve 200 mM chondroitin sulfate phantoms with varying pH. It can be observed that the intensity and the shape of the MTRasym of the hydroxyl group are pH dependent, suggesting that the CEST effect of the OH-groups from 50 Hz to 450 Hz from the bulk water resonance varies with pH. The vertical dashed line at 225 Hz indicates the center frequency of the OH-group. In general, the asymmetry curves of low pH phantoms show a sharp peak centered at 100 Hz to 120 Hz, which becomes broader and flatter with a center around 150 Hz to 180 Hz in the mid-range pH values of 6.52 to 7.36 and then returns to its initial shape at pH greater than 7.5. Additionally the CEST effect of the amide protons of the GAG molecules is visible in the z-spectra at 960 Hz (= 3.2 ppm). The CEST effect of the GAG NH-groups is typically much smaller than the one of the hydroxyl protons (up to two orders in magnitude) (7). Fig. 1b shows the T2-weighted reference image of the phantom, where the numbers indicate the phantom pH values. The MTRasym map at the frequency offset of 225 Hz (= 0.75 ppm) from the water resonance is displayed in Fig. 1c. The MTRasym map demonstrates the pH-dependence of the gagCEST signal. gagCEST pH-dependence curves were created by plotting the results from the CEST asymmetry analysis against pH: Fig. 1d displays the MTRasym maximum signal, the intensity at an offset of 225 Hz and the integral (from 50 Hz to 450 Hz offset) as a function of pH. The hydroxyl groups of the chondroitin sulfate show non-linear pH dependence. The gagCEST MTRasym signal of all three curves (maximum, signal intensity at 225 Hz offset and integral from 50 Hz to 450 Hz) increases until pH = 7.0 to 7.2, where they reach a maximum, before it decreases at pH values greater than 7.55.

Figure 1.

Chondroitin sulfate phantom measurements. (a) MTRasym curves at different pH. (b) T2-weighted reference image of the twelve chondroitin sulfate phantoms. The numbers in the tubes indicate the pH value. (c) The MTRasym map of the phantoms (at a frequency offset of 225 Hz) shows the pH dependency of the gagCEST signal. (d) The gagCEST pH-dependency curves shown as the maximum intensity, the signal intensity at on offset of 225 Hz and as an integral from 50 Hz to 450 Hz of the MTRasym.

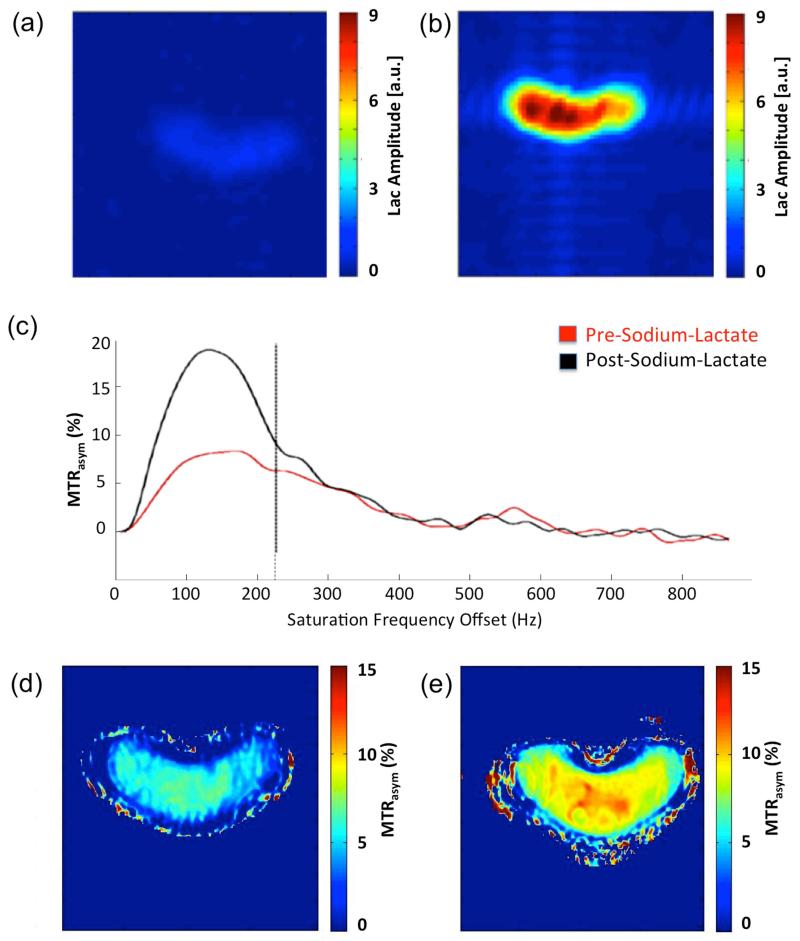

Figs. 2a and 2b show the Lac distribution in an IVD before and after Na-Lac injection, respectively. The Lac imaging analysis indicates a 10-fold increase in the Lac signal post injection, demonstrating that Lac was successfully incorporated into the IVD. Fig. 2c shows the MTRasym plot from a porcine IVD before and after Na-Lac injection. After Na-Lac application, the MTRasym of the hydroxyl groups increases, which can also be seen in the MTRasym maps at the offset of 0.75 ppm before (Fig. 2d) and after (Fig. 2e) the injection of Na-Lac in the IVD.

Figure 2.

IVD experiments before and after Na-Lac injection. (a) Sel-MQC spectral edited Lac signal amplitude before and (b) after injection Na-Lac into the IVD. After Na-Lac application the Lac amplitude increased by a factor 10. (c) MTRasym plots before and after Na-Lac injection. MTRasym maps at a saturation frequency offset of 0.75 ppm (d) before and (e) after Na-Lac application into IVD.

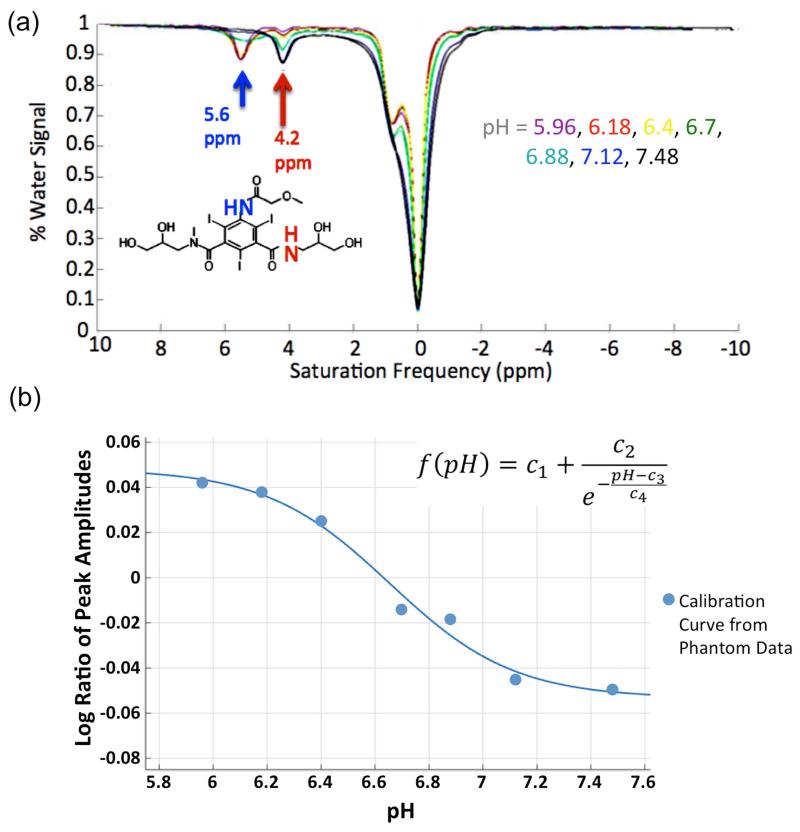

Z-spectra of the 200 mM Iopromide phantoms with different pH are shown in Fig. 3a. The CEST effect of NH-groups at 4.2 ppm and 5.6 ppm from the water resonance is pH-dependent. At low pH the peak centered at 5.6 ppm is sharp and has a greater CEST effect than the peak at 4.2 ppm. With increasing pH, the peak at 5.6 ppm flattens and then nearly disappears at pH greater than 7.12, while the peak at 4.2 ppm consistently increases in amplitude. The logarithm of the ratio of peak amplitudes was calculated (Equation [2]) and plotted against the pH (Fig. 3b). Sigmoidal fitting of the data resulted in R2 = 0.98. The OH-groups of Iopromide (in the frequency range between 50 Hz to 500 Hz from the bulk water resonance) also show a pH-dependency (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Results of the Iopromide phantom measurements. (a) z-spectra of Iopromide at different pH. The amide groups at the saturation frequency offset 4.6 ppm and 5.4 ppm from the bulk water show a pH dependent signal amplitude. The chemical structure of Iopromide with the two pH depended amide groups is shown in the lower left corner. (b) The logarithmic ratio of the amplitude of the two amide groups correlate sigmoidal with the pH (R2 = 0.98). The applied sigmoidal fit equation is shown in the right upper corner of the plot (c1-c4 = fit constants).

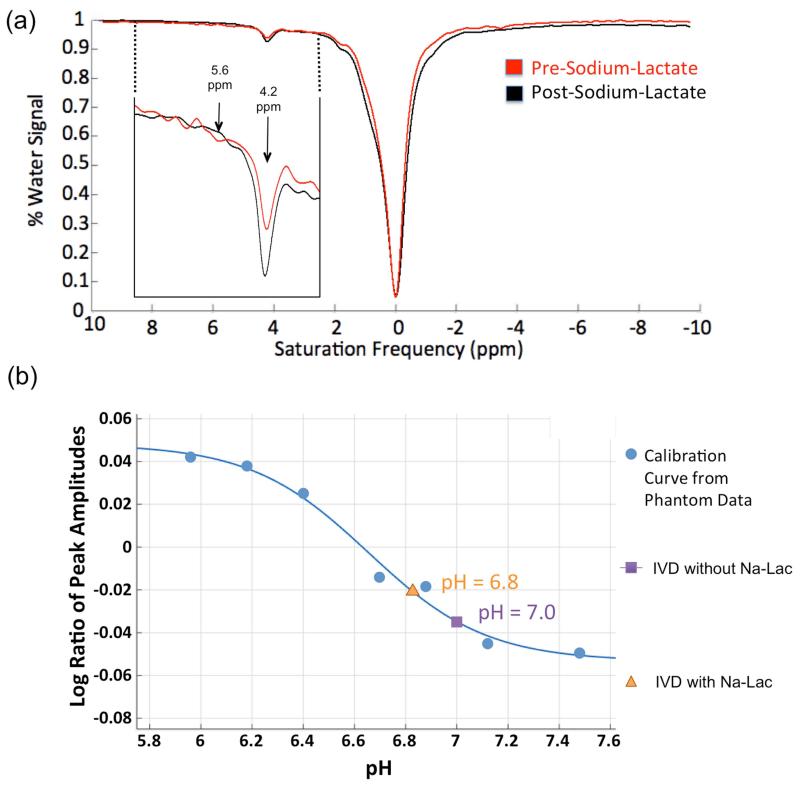

Z-spectra of an IVD with Iopromide pre- and post Na-Lac injection can be seen in Fig. 4a. The peaks of the Iopromide amide groups are visible in the z-spectra. The amplitude of the peak at 4.2 ppm decreases while the broader peak at 5.6 ppm increases after Na-Lac was injected into the IVD. This result is consistent with the trends from the Iopromide phantom studies. The pH drops from pH = 7.0 ± 0.2 before to pH = 6.8 ± 0.2 after Na-Lac is injected in the IVD (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

IVD experiments using Iopromide before and after Na-Lac injection. (a) z-spectrum of IVD containing Iopromide pre- and post- Na-Lac application. The smaller image in the left corner shows the zoomed detail of the z-spectrum where the amide protons of the Iopromide are detectable. (b) pH estimation of the IVD pre- and post- Na-Lac injection as determined using the Iopromide phantom calibration curve.

After the completion of the MR measurements, a tissue pH meter and Litmus paper were used to measure the pH of the IVDs whose pH had been manipulated with Na-Lac (pH = 6.5 ± 0.1) as well as the pH of three IVDs whose pH had not been manipulated with Na-Lac (controls). The pH of the control IVDs was 8.0 ± 0.2 and the pH of the IVDs injected with Na-Lac ranged from 7.0 to 7.5 (mean 7.3 ± 0.3). The results of the pH measurements are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the pH measurements

| Type | pH |

|---|---|

| Lac solution (1M) | 6.5 ± 0.1 |

| IVD pH ((24)) | 7.2-7.7 |

| IVD control (no Lac) | 8.0 ± 0.2 |

| IVD (with Lac) | 7.3 ± 0.3 |

| IVD Iopromide (no Lac) | 7.0 ± 0.3 |

| IVD Iopromide (with Lac) | 6.8 ± 0.3 |

DISCUSSION

The pH-dependence of the gagCEST signal and the use of Iopromide as a pH-sensitive agent were studied using phantoms and IVD specimens. The results report on, what is to our knowledge, the first description of the pH-dependence of gagCEST imaging and the first use of the Iopromide contrast agent for CEST MR-based pH estimation of the IVD specimens.

Studies have shown that the production of proteoglycan is correlated to the pH and lower pH values (<6.8) in the IVD results in a decreased proteoglycan synthesis (23, 24). The low pH in the disc may be the first step in IVD degeneration. The synthesis of proteoglycans is inhibited and leads to a decreased total GAG content in the IVD over time. This can then be detected with non-invasive MRI techniques sensitive to the GAG content: T1ρ, gagCEST or 23Na MR imaging. It has also been shown that decreased pH values in IVDs lead to deregulated activity of metallometaproteinases, which can result to a faster degeneration of collagen in the discs (23).

The exact relationship between low pH and lower back pain still remains unclear. In a recent systematic review focusing on the relationship between low IVD pH and low back pain in which seven publications focusing on this topic were analyzed, the authors came to the hypothesis that low pH does indeed result in lower back pain (25). The cause of pain by low pH is explained by three different mechanisms: 1. Low pH caused by higher Lac levels stimulates the muscle tension, which leads to pain. 2. The low pH directly affects the nerves roots, which results also in pain. 3. The lower pH changes the metabolism, resulting to neuronal death and pain. To support the above hypotheses more studies are necessary for which non-invasive imaging techniques to detect pH in the IVD would be advantageous. In this study, we successfully demonstrated on an ex vivo porcine model that IVD pH can be detected using gagCEST and the CEST effect of Iopromide.

The MTRasym curves from the chondroitin phantom measurements resulted in considerable differences in the gagCEST effect at varying pH. The gagCEST pH-dependency is non-linear and thus differences in pH could be detected using gagCEST. The gagCEST amplitude is also dependent on the amount of the PG (7, 8, 9) and therefore additional measurements, based on T1ρ or 23Na MRI, are necessary to measure the GAG content (26, 27, 28, 29, 30). A robust GAG content correction method to measure pH using gagCEST needs to be developed in the future.

The Iopromide phantom studies demonstrated a sigmoidal change of CEST effect (by analyzing the logarithmic ratio of the amplitudes) with pH from 6 to 7.5, which makes the probe interesting for pH measurement in the physiological range.

When diluted Iopromide (200mM) was injected directly into the IVD specimens, the CEST effect of the two measurable amide groups and a pH change could be detected after Na-Lac injection. While the reported pH using Iopromide CEST imaging was not consistent with the pH of the IVD reported by Litmus paper/tissue pH meter, it was reasonably close to the average pH of a IVD in vivo as reported in literature (24). Iopromide is a FDA approved X-Ray/CT contrast agent, which gives the substance interesting potential to be used as a pH-marker in combination with CEST MRI for clinical studies.

The GAG NH-groups show a CEST effect 3.2 ppm from the main bulk water, which is much smaller than that of the OH-groups (Fig. 1a). The Iopromide amide proton resonances are at 4.2 ppm and 5.6 ppm and therefore 1 ppm separated from the CEST effect of the GAG NH-groups. At higher magnetic field strength (3T and above) we expect a large enough spectral separation to distinguish between GAG and Iopromide. The hydroxyl groups of Iopromide show also a pH dependent CEST effect (Fig. 3a). Therefore care must be taken in evaluation of the gagCEST effect in experiments, where Iopromide is already applied. Due the overlapping resonances of the OH-groups in the z-spectrum, a spectral discrimination between GAG and Iopromide might not be possible, especially in specimens or in in vivo studies.

A potential limitation of the technique is the low signal to noise ratio of the 5.6 ppm CEST peak, which decreases with increasing pH (see Fig. 3a). Especially for in vivo applications, high signal-to-noise ratio z-spectra are required to analyze the two amide CEST peaks. This study shows the proof of principle of detecting Iopromide in IVD specimens after injection. For in vivo experiments, the sensitivity of the technique needs to be further addressed.

The pH-values of the IVDs were measured after MR imaging was completed. The methods used to report pH had some drawbacks: The tissue pH meter used was designed for larger tissue samples and therefore a pH error of ±0.2 is assumed for the measurement and the pH Litmus paper only measured pH qualitatively and in increments of 0.5 pH units. The pH of the control IVDs was slightly higher than the average pH of the IVD in vivo reported in the literature (24), but the pH measurements are consistent with a decrease in pH that we expected to find after injecting an acid directly into the IVDs.

The injection of 1 M Na-Lac into the IVD specimens simulates the in vivo condition only to a limited extent and differs from an in vivo scenario where anaerobic glycolysis produces increased Lac levels with an associated pH drop. The Na-Lac solution injected had a pH value of 6.5 (see Tab. 1) and was used to decrease the overall pH value in the IVD in order to investigate if general changes in the gagCEST signal or the CEST effect of Iopromide can be detected. To mimic a better in vivo situation, gagCEST experiments could be carried out on disc tissue from patients with discogenic pain, similar to the study by Keshari et al., who investigated Lac and other metabolite levels using NMR (4).

Recent research suggests that certain biochemical changes within the IVD, such as a drop in pH as a result of increased Lac accumulation, not only catalyze IVD degeneration, but can also serve as markers of pain. The gagCEST signal amplitude varies with pH, and could therefore be one way to detected pH changes in IVD non-invasively when combined with correction methods for measuring GAG content. Iopromide CEST imaging is independent of the local concentration of macromolecules and showed potential in reporting pH in IVD specimen studies. In vivo experiments will face the challenge of incorporating the Iopromide solution into the IVD and may require localized injection, as the substance is not taken up in the IVDs after intravenous application. However the ability to measure the pH of the IVD using the FDA approved probe Iopromide combined with CEST imaging could have clinical value in the early prediction of pain and IVD degeneration and could therefore help in treatment planning and preventative care.

CONCLUSION

In this study, two approaches were investigated to detect pH changes in the IVD using CEST MRI: The pH-dependence of the gagCEST signal and the use of Iopromide as an exogenous pH-sensitive agent. The gagCEST signal showed a non-linear signal amplitude change with varying pH. gagCEST is sensitive to detect pH changes in IVD and could therefore be a technique to measure IVD pH in vivo, when the signal is corrected for the GAG content potentially using Sodium or T1ρ MR imaging. The CEST effect of Iopromide, which has two pH-dependent amino groups, was studied in phantoms and the probe seems to be a promising molecule to measure pH in IVDs. CEST MRI can measure the pH and the estimation is independent of the probes local concentration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dean Sherry, Ph.D. at UT Southwestern, Dallas, for the initial discussion about this project. This publication was supported by NIH R01 AG017762 (SM).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354:581–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peterson CK, Bolton JE, Wood AR. A cross-sectional study correlating lumbar spine degeneration with disability and pain. Spine. 2000;25:218–223. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200001150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luoma K, Riihimäki H, Luukkonen R, Raininko R, Viikari-Juntura E, Lamminen A. Low back pain in relation to lumbar disc degeneration. Spine. 2000;25:487–492. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keshari KR, Lotz JC, Link TM, Hu S, Majumdar S, Kurhanewicz J. Lactic acid and proteoglycans as metabolic markers for discogenic back pain. Spine. 2008;33:312–317. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816201c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams MA, Roughley PJ. What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it? Spine. 2006;31:2151–2161. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000231761.73859.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung KM. The relationship between disc degeneration, low back pain, and human pain genetics. Spine J. 2010;10:958–960. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration in vivo by chemical exchange-dependent saturation transfer (gagCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2266–2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707666105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M, Chan Q, Anthony MP, Cheung KM, Samartzis D, Khong L. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan distribution in human lumbar intervertebral discs using chemical exchange saturation transfer at 3 T: feasibility and initial experience. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:1137–1144. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saar G, Zhang B, Ling W, Regatte RR, Navon G, Jerschow A. Assessment of glycosaminoglycan concentration changes in the intervertebral disc via chemical exchange saturation transfer. NMR Biomed. 2012;25:255–261. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward KM, Balaban RS. Determination of pH using water protons and chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:799–802. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200011)44:5<799::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aime S, Barge A, Delli Castelli D, Fedeli F, Mortillaro A, Nielsen FU, Terreno E. Paramagnetic lanthanide(III) complexes as pH-sensitive chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) contrast agents for MRI applications. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:639–648. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun PZ, Sorensen AG. Imaging pH using the chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI: Correction of concomitant RF irradiation effects to quantify CEST MRI for chemical exchange rate and pH. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:390–397. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou J, Payen JF, Wilson DA, Traystman RJ, van Zijl PCM. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat Med. 2003;9:1085–1090. doi: 10.1038/nm907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun PZ, Zhou J, Huang J, Van Zijl P. Simplified quantitative description of amide proton transfer (APT) imaging during acute ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:405–410. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jokivarsi KT, Gröhn HI, Gröhn OH, Kauppinen RA. Proton transfer ratio, lactate, and intracellular pH in acute cerebral ischemia. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:647–653. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai K, Haris M, Singh A, Kogan F, Greenberg JH, Hariharan H, Detre JA, Reddy R. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat Med. 2012;18:302–306. doi: 10.1038/nm.2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheth VR, Liu G, Li Y, Pagel MD. Improved pH measurements with a single PARACEST MRI contrast agent. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2012;7:26–34. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen LQ, Sheth VR, Howison CM, Kuo PH, Pagel MD. Measuring in vivo tumor pHe with a DIACEST MRI contrast agent; Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. 2011.p. 7315. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sivan SS, Merkher Y, Wachtel E, Urban JP, Lazary A, Maroudas A. A needle micro-osmometer for determination of glycosaminoglycan concentration in excised nucleus pulposus tissue. Eur Spine J. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2714-8. DOI 10.1007/s00586-013-2714-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, Van Zijl PCM. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Q, Shungu DC, Van Zijl PC, Bhujwalla ZM, Glickson JD. Single-scan in vivo lactate editing with complete lipid and water suppression by selective multiple-quantum-coherence transfer (Sel-MQC) with application to tumors. J Magn Reson B. 1995;106:203–211. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melkus G, Mörchel P, Behr VC, Kotas M, Flentje M, Jakob PM. Sensitive J-coupled metabolite mapping using Sel-MQC with selective multi-spin-echo readout. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:880–887. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urban JPG. The role of the physicochemical environment in determining disc cell behaviour. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:858–864. doi: 10.1042/bst0300858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urban JPG, Smith S. Fairbank JCT. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc. Spine. 2004;29:2700–2709. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146499.97948.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang CZ, Li H, Tao YQ, Zhou XP, Yang ZR, Li FC, Chen QX. The relationship between low pH in intervertebral discs and low back pain: a systematic review. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:952–956. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.32401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johannessen W, Auerbach JD, Wheaton AJ, Kurji A, Borthakur A, Reddy R, Elliott DM. Assessment of human disc degeneration and proteoglycan content using T1rho-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2006;31:1253–1257. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000217708.54880.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blumenkrantz G, Li X, Han ET, Newitt DC, Crane JC, Link TM, Majumdar S. A feasibility study of in vivo T1rho imaging of the intervertebral disc. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majumdar S. Magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy of the intervertebral disc. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:894–903. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borthakur A, Mellon E, Niyogi S, Witschey W, Kneeland JB, Reddy R. Sodium and T1rho MRI for molecular and diagnostic imaging of articular cartilage. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:781–821. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noebauer-Huhmann IM, Juras V, Pfirrmann CW, Szomolanyi P, Zbyn S, Messner A, Wimmer J, Weber M, Friedrich KM, Stelzeneder D, Trattnig S. Sodium MR imaging of the lumbar intervertebral disk at 7 T: correlation with T2 mapping and modified Pfirrmann score at 3 T--preliminary results. Radiology. 2012;265:555–564. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]