Abstract

Objective

To examine the patterns of consumption of foods high in solid fats and added sugars (SoFAS) in Brazil.

Design

Cross-sectional study; individual dietary intake survey. Food intake was assessed by means of two non-consecutive food records. Foods providing >9·1 % of energy from saturated fat, or >1·3 % of energy from trans fat, or >13 % of energy from added sugars per 100 g were classified as high in SoFAS.

Setting

Brazilian nationwide survey, 2008–2009.

Subjects

Individuals aged ≥10 years old.

Results

Mean daily energy intake was 8037 kJ (1921 kcal), 52 % of energy came from SoFAS foods. Contribution of SoFAS foods to total energy intake was higher among women (52 %) and adolescents (54 %). Participants in rural areas (43 %) and in the lowest quartile of per capita family income (43 %) reported the smallest contribution of SoFAS foods to total energy intake. SoFAS foods were large contributors to total saturated fat (87 %), trans fat (89 %), added sugar (98 %) and total sugar (96 %) consumption. The SoFAS food groups that contributed most to total energy intake were meats and beverages. Top SoFAS foods contributing to saturated fat and trans fat intakes were meats and fats and oils. Most of the added and total sugar in the diet was supplied by SoFAS beverages and sweets and desserts.

Conclusions

SoFAS foods play an important role in the Brazilian diet. The study identifies options for improving the Brazilian diet and reducing nutrition-related non-communicable chronic diseases, but also points out some limitations of the nutrient-based criteria.

Keywords: Food consumption, Nutrient profiling, Added sugar, Brazil, Dietary survey

Overweight and other nutrition-related non-communicable diseases represent major health problems in Brazil( 1 ). In parallel with deep social and economic changes, this country has experienced a transition from the traditional dietary pattern to diets high in saturated fat and sugar( 2 ). Major efforts focused on improving diet are being made( 3 ), specifically the issuing of the Brazilian Dietary Guidelines in 2006( 4 ) and other regulations aimed at reducing trans fats and sodium in selected processed foods( 5 ).

In recent decades, Brazil has experienced rapid growth in income, increased urbanization and major changes in the overall food system. These changes are linked with rapid increases in the use of modern supermarkets and increased mass media promotion of food and beverage products( 6 – 8 ). Consequently, countless sources of commercial foods with high energy content and low nutrient density are broadly available in different social environments. Also, income growth has brought increased access to these foods and beverages, even among very poor families assisted by cash transfer programmes( 9 ).

A large part of the newly available processed food items are foods that provide energy from solid fats and added sugars (hereafter SoFAS)( 10 , 11 ) and the purchase of these food items is increasingly found in Brazil's household food expenditure surveys. Monteiro et al.( 12 ) found that between 1987–1988 and 2002–2003 the contribution of ultra-processed foods to total household energy availability increased by 46 %, going from 19·2 % to 28·0 %, replacing the intake of unprocessed and minimally processed foods. Furthermore, in Brazil, sugar and soft drinks consumption was responsible for 13·4 % of household energy availability and was correlated with obesity prevalence (r = 0·60; P = 0·0 0 1)( 13 ). According to analysis carried out by Levy et al.( 14 ), high household availability of sugar was associated with household total energy availability 40 to 60 % over the recommended value.

The goal of the present work is to examine the patterns of consumption of foods high in SoFAS in the first Brazilian nationally representative Individual Dietary Survey (IDS). This analysis represents the first attempt to define a food- and nutrient-based measure of dietary intake in Brazil.

Methods

The present study analyses data from the first IDS carried out by the IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica; Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) along with the 2008–2009 Brazilian Household Budget Survey (HBS), which investigated a probabilistic sample of 55 970 households selected by a two-stage complex cluster sampling design( 15 ). Because of the specific requirements for implementation of the IDS, a sub-sample corresponding to 25 % of the households included in the 2008–2009 HBS was randomly selected for the dietary survey, which was answered by individuals aged ≥10 years. Also, it was ensured that all sectors selected for the HBS were represented in the IDS 2008–2009 sample and that the census tracts, the primary sampling units, were equally allocated among the four quarters of the survey to guarantee that all strata were represented at all quarters to reproduce seasonal variations food consumption. Therefore, a representative sample of the Brazilian population totalling 34 003 individuals from 13 569 households composed the sample examined in the IDS 2008–2009( 15 ).

The IDS protocol was approved by the Ethics Research Committee from the Institute of Social Medicine (Rio de Janeiro State University).

Assessment of food intake

Individuals aged ≥10 years residing in the households selected for the survey completed two non-consecutive food diaries on pre-determined days spanning one week. They were asked to report all foods and beverages consumed and to include information on time, amount and place of intake (inside or outside home). Details on the preparation mode were required for specific foods, mainly meats and vegetables. Additionally, information on the consumption of sugar and/or artificial sweetener was collected using a separate question (‘What do you use more frequently: sugar, artificial sweetener, both, or none?’). Information on water drinking and use of nutritional supplements was not collected.

During in-person interviews, trained interviewers reviewed the food records and probed the participants on usually forgotten foods. When the dietary record presented periods longer than 3 h without any reported food intake, the respondents were asked either to confirm that no foods/beverages were consumed during that period or to provide the necessary information. The data storage was done on specific software with a database containing approximately 1500 food and beverages, 106 measurements units and fifteen modes of preparation. However, the interviewers were able to include new food items that were not found on the database( 16 ). Partial analyses were performed during data collection to check data quality. Details of the pre-test, the interviewer training process and the validation study of the data collection protocol are presented in an IBGE publication( 15 ).

Food composition estimates were based on the Nutrition Coordination Center Nutrient Databank( 17 ) and on the Brazilian Food Composition Table( 18 ). Portion size measures came from various Brazilian publications and/or direct weighing of some foods and dishes( 19 , 20 ). For each food a ‘standard unit’ was also defined, which was imputed to atypical units of measurement (e.g. a unit of rice). A series of decisions on dilutions of common beverages (fruit for fruit juice, powered cocoa for chocolate drinks, etc.) were standardized based on Brazilian research; for example, to prepare a glass of milk (240 ml), two tablespoons of powdered milk were added to 200 ml of water( 15 ). Nutritional composition for dishes based on meat, fish and poultry, and cooked or braised vegetables were estimated with the addition of soyabean oil( 17 ).

Characterizing foods with regard to saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar content

The criteria used to identify foods high in saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar were adapted from the standards proposed by the International Choices Programme( 21 ), which evaluates foods according to the nutritional profile of specific food groups (Table 1). In this analysis, the estimations excluded the naturally occurring trans fat from milk and meat. From the 2070 unique foods, dishes and beverages reported in the IDS, alcoholic beverages (n 23) and no sugar- or fat-added fresh fruits, vegetables, roots and tubers (n 254) were excluded, resulting in 1793 individual food/beverage items for profiling.

Table 1.

Cut-off limits applied to classify excessive saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar content in foods*,†

| Criteria | Energy | Saturated fat | Trans fat | Added sugar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/100 g) | (g/100 g) | (g/100 g) | ||

| Generic | ||||

| NA | 9·1 % of total energy | 1·3 % of total energy | 13 % of total energy | |

| Specific | ||||

| Beverages | 84 kJ (20 kcal) | 0·78 | 0·1 | NA |

| Cheeses | NA | 15 | 0·1 | NA |

| Fats, oils and fat-containing spreads | NA | 30 % of total fat | 1·3 % of total energy | NA |

| Fried potatoes and savoury snacks | NA | 0·78 | 0·1 | NA |

| Milk and milk/soya/yoghurt-based beverages | NA | 1·4 | 0·1 | 5 |

| Ready-to-eat cereals | NA | 0·78 | 0·1 | 20 |

NA, not applicable.

The criteria were not applied to alcoholic beverages, fresh fruits, legumes and unprocessed potatoes, roots and tubers.

Based on Roodenburg et al.( 21 ).

The International Choices Programme applies threshold criteria based on the proportion of energy provided by the targeted nutrients in 100 g of food. The criteria for added sugar and trans fat were based on the WHO recommendations for healthy eating promotion( 22 ). Additionally, the most recent (2010) recommendation on saturated fat by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)( 11 ), which is slightly more stringent than that proposed in the International Choices Programme, was considered. Therefore, the classification of SoFAS foods was completed using the following two-step process.

First step: Generic energy-based criteria

The WHO recommends that the consumption of trans fat should be less than 1 % and of added sugar under 10 % of total daily energy intake( 22 ). The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend saturated fat intake of no more than 7 % of total energy intake( 11 ). To account for the fact that these are whole diet recommendations, rather than recommendations for any single food item, an additional 30 % over these limits was allowed to classify foods as excessive or allowable with respect to the energy provided by saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar( 21 ). Therefore, foods were considered as source of excessive saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar (SoFAS) if they provided more than 9·1 % of energy from saturated fat, or more than 1·3 % of energy from trans fat, or more than 13 % of energy from added sugar per 100 g of food (Table 1).

Second step: Criteria for specific food groups

Specific food groups were classified according to alternative criteria. Some of these criteria were based on the ‘level of insignificance’ as a means of ensuring that low energy- or nutrient-dense products would not be (mistakenly) excluded( 21 ). The cut-off point for the ‘level of insignificance’ was 5 % of the daily recommendation in grams per 100 g of food considering the WHO/FAO recommendation of 8368 kJ/d (2000 kcal/d)( 22 ). For example, the ‘level of insignificance’ for trans fat is 0·1 g/100 g of food (5 % of recommended daily allowance of 2 g)( 22 ). Correspondingly, the cut-off points for the ‘level of insignificance’ of added sugar and saturated fat are 2·5 g and 0·78 g/100 g of food, respectively. Specific criteria were defined for specific food groups: beverages, cheeses, fats and oils, fried potatoes and savoury snacks, milk/soya/yoghurt-based beverages and ready-to-eat cereals( 21 ) (Table 1).

-

1.

Beverages (except milk/soya/yoghurt-based beverages): classified according to the ‘level of insignificance’ for saturated fat and trans fat. Additionally, beverages providing more than 84 kJ (20 kcal) per 100 ml (equivalent to 5 g of sugars) were classified as SoFAS beverages.

-

2.

Cheeses: saturated fat cut-off point was 15 g/100 g and trans fat cut-off point was the ‘level of insignificance’ of 0·1 g/100 g. No criteria for added sugar were applied.

-

3.

Fats and oils: considered as source of excessive saturated fat or trans fat if their content of saturated fat was over 30 % of total fat or the energy provided by trans fat was over 1·3 % of total energy.

-

4.

Fried potatoes and other fried starchy vegetables and savoury snacks: considered as source of excessive saturated fat and trans fat if the content of saturated fat was over 0·78 g/100 g or the content of trans fat was above 0·1 g/100 g.

-

5.

Milk and dairy (including milk/soya/yoghurt-based beverages and excluding cheeses): saturated fat cut-off limit was 1·4 g/100 g, while the trans fat cut-off point was the ‘level of insignificance’ of 0·1 g/100 g and added sugar must be less than 5 g/100 g.

-

6.

Ready-to-eat cereals: considered as SoFAS foods if they provided more than 0·78 g of saturated fat, more than 0·1 g of trans fat or more than 20 g of added sugar in 100 g of food.

Food grouping

Food grouping was based on the groups adopted by the Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina, USA. This system of grouping foods and beverages was based on the nine major USDA food groups, which were disaggregated into food groups according to nutritional features and usual dietary habits (MM Slining and BM Popkin, unpublished results). For this analysis, foods and beverages were aggregated into twenty-eight groups (see Supplementary Materials, Table 1 for a detailed description of groups and foods included in each group).

Statistical analysis

The present analysis considered the first day of food records for 34 003 individuals and took into account sex and three age groups (adolescents, age 10–19 years; adults, age 20–64 years; and elders, age ≥65 years). The prevalence of intake of allowable and SoFAS food groups, the average percentage contribution to total energy intake and the energy provided by saturated fat, trans fat, added sugar and total sugar were estimated for each food group for the total population and across age groups. Additionally, mean estimates of total energy intake (kJ/kcal) and proportion of energy from SoFAS foods ( %) were calculated for area of residence (urban v. rural), geographic region (North, Northeast, Southeast, South and Central-West), level of education (less than eight v. eight or more years of education), quartile of per capita family income (which was estimated by summing income earned by all family members and dividing by the number of persons in the family), and according to the place of food consumption (in the household only v. eating away from home at least once in the first day of recorded intake). The differences in mean energy intake and total energy intake from SoFAS foods across the categories of age, sex, income, education, geographic region and area of residence (urban or rural) were tested by univariate linear regression models, having energy intake and proportion of total energy intake from SoFAS foods as dependent variables and the explanation variables as independent variables. All statistical analyses considered the sample weights and design effect and were performed using survey procedures in the statistical software package SAS release 9·3.

Results

Sixty-six per cent of the foods cited in the IDS were classified as SoFAS (see Supplementary Materials, Table 1). Mean daily energy intake was 8037 kJ (1921 kcal) and, on average, 52 % of energy came from SoFAS foods. Individuals living in rural areas (43 %), in the lowest quartile of per capita family income (43 %) and from the Northern region (45 %) reported the smallest contribution of SoFAS foods to total energy intake. The highest intakes of SoFAS foods were observed among individuals in the highest quartile of per capita family income (57 %), in the country's Southern region (56 %), and among adolescents (54 %) and women (52 %). Contribution of SoFAS foods to total energy intake was lower for individuals who ate only at home compared with those who reported consuming away-from-home food (55 % v. 48 %; P < 0·01; Table 2).

Table 2.

Population sociodemographic characterization and means for total energy intake, energy provided by and contribution to total energy intake from SoFAS foods; Brazil, 2008–2009

| Mean total energy intake*,† | Mean energy from SoFAS*,‡ foods | Mean contribution of SoFAS foods to | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | kJ | kcal | KJ | kcal | total energy intake*,§,∥ (%) | |

| Brazil (total) | 8037 | 1921 | 4188 | 1001 | 52 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 48 | 8912 | 2130 | 4481 | 1071 | 49 |

| Female | 52 | 7222 | 1726 | 3916 | 936 | 52 |

| Age group | ||||||

| Adolescent (10–19 years) | 21 | 8611 | 2058 | 4862 | 1162 | 54 |

| Adult (20–64 years) | 69 | 8029 | 1919 | 4096 | 979 | 50 |

| Elder (≥65 years) | 9 | 6770 | 1618 | 3301 | 789 | 48 |

| Area of residence | ||||||

| Urban | 83 | 8025 | 1918 | 4305 | 1029 | 52 |

| Rural | 17 | 8113 | 1939 | 3590 | 858 | 43 |

| Geographic region¶ | ||||||

| North | 8 | 8891 | 2125 | 4033 | 964 | 45 |

| Northeast | 28 | 7920 | 1893 | 3761 | 899 | 46 |

| Southeast | 43 | 8012 | 1915 | 4347 | 1039 | 53 |

| South | 15 | 7962 | 1903 | 4611 | 1102 | 56 |

| Central-West | 7 | 7891 | 1886 | 4167 | 996 | 50 |

| Years of education | ||||||

| <8 years | 51 | 7740 | 1850 | 3728 | 891 | 47 |

| ≥8 years | 49 | 8355 | 1997 | 4674 | 1117 | 55 |

| Per capita family income** | ||||||

| Quartile 1 | 25 | 7627 | 1823 | 3397 | 812 | 43 |

| Quartile 2 | 25 | 8104 | 1937 | 4058 | 970 | 49 |

| Quartile 3 | 25 | 8134 | 1944 | 4418 | 1056 | 53 |

| Quartile 4 | 25 | 8284 | 1980 | 4883 | 1167 | 57 |

| Location of consumption | ||||||

| Household only | 40 | 7594 | 1815 | 3728 | 891 | 48 |

| Household + away from home | 60 | 8699 | 2079 | 4870 | 1164 | 55 |

*Differences tested by univariate linear regression models: dependent variables were energy intake and proportion of total energy intake from SoFAS; independent variables were age group, sex, urbanicity, geographic region, education, income and location of consumption.

†P < 0·01 for comparisons between categories of gender, age groups, urban v. rural, education and location of consumption.

‡SoFAS: high in saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar (see Table 1).

§Contribution of SoFAS foods to total energy intake = (energy from SoFAS foods/total energy intake) × 100.

∥P < 0·01 for all comparisons, except Central-West region v. Southeast region.

¶Mean energy intake in the Northern region higher than all other regions (P < 0·01).

**Mean energy intake in quartile 1 < quartile 2, quartile 3 and quartile 4 with P < 0·01; quartile 2 = quartile 3 = quartile 4 (P > 0·05).

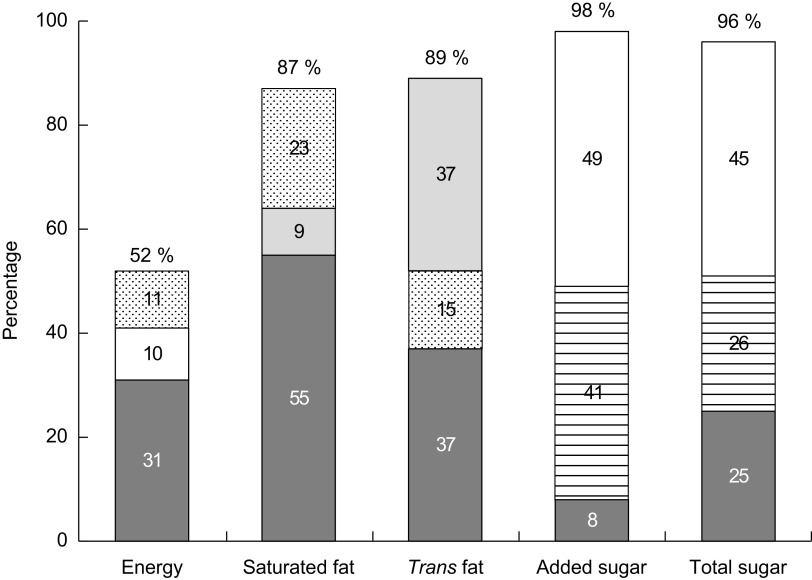

On average, 9·5 % of total energy intake came from saturated fat, 1·4 % from trans fat and 7·2 % from added sugar, and SoFAS foods provided the majority of the energy coming from saturated fat (87 %), trans fat (89 %), added sugar (98 %) and total sugar (96 %).

Considering all foods, the groups that contributed most to total energy intake were rice, corn and other cereal dishes, beverages, meats, legumes and breads. The main food groups in saturated fat intake were meats, sweets and desserts, fats and oils, milk and dairy, and processed meat. The top food groups in the intake of trans fat were fats and oils, meats, sweets and desserts, breads, savoury snacks and poultry. Sweets and desserts, beverages, milk and dairy, sugar, syrups and preserves, and savoury snacks were the food groups that contributed most to the consumption of added sugar. Finally, the major food groups in the consumption of total sugar were beverages, sweets and desserts, and milk and dairy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Top food groups* according to the contribution (%) to total intake of energy and to energy provided by saturated fat, trans fat, added sugar and total sugar; Brazil, 2008–2009

| Energy | Saturated fat | Trans fat | Added sugar | Total sugar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food group | % | Ranking | % | Ranking | % | Ranking | % | Ranking | % | Ranking | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rice, corn, and other cereal dishes | 15 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Beverages | 13 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 10 | 37 | 2 | 46 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Meats | 11 | 3 | 23 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legumes | 10 | 4 | 3 | 10 | NA | NA | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breads | 9 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sweets and desserts | 7 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 13 | 3 | 41 | 1 | 27 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Poultry | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Milk and dairy | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 14 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fresh fruits and vegetables | 4 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pasta and noodles | 3 | 10 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starchy vegetables | 3 | 10 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fats and oils | NA | 9 | 3 | 36 | 1 | NA | NA | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Processed meat | NA | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 6 | NA | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cheeses | NA | 5 | 8 | 2 | 10 | NA | 1 | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burgers and sandwiches | NA | 3 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Savory snacks | NA | NA | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugar, syrups, preserves | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| All other foods (%) | 15 | 18 | 7 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

NA, not applicable.

Includes allowable and SoFAS foods (high saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar; see Table 1).

Considering only the SoFAS food groups, the major contribution to total energy intake was provided by SoFAS beverages and meats; the SoFAS food groups that contributed most to saturated fat and trans fat intakes were the meats and fats and oils; finally, the SoFAS food groups that contributed most to added and total sugar intakes were sweets and desserts and beverages (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Contribution (%) of top SoFAS food groups ( , meats;

, meats;  , beverages;

, beverages;  , sweets and desserts;

, sweets and desserts;  , fats and oils;

, fats and oils;  , all other SoFAS foods) to total intake of energy and to energy provided by saturated fat, trans fat, added sugar and total sugar; Brazil, 2008–2009 (SoFAS, high in saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar)

, all other SoFAS foods) to total intake of energy and to energy provided by saturated fat, trans fat, added sugar and total sugar; Brazil, 2008–2009 (SoFAS, high in saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar)

Adolescents presented higher proportional contribution of SoFAS foods to energy intake and added sugars than adults and elders (P < 0·01). On the other hand, SoFAS foods provided roughly equal proportions of energy to total saturated fat and trans fat across the age groups. Considering the contribution of foods groups to the intake of the analysed components, the main difference across the age groups was observed for SoFAS beverages and sweets and desserts. Combined, these groups provided 20 % of adolescents’ total energy intake, but just 15 % and 14 % of total energy intake among adults and elders, respectively (see Supplementary Materials, Table 2).

The most commonly consumed allowable food groups were rice and cereal dishes, legumes, breads and beverages. The most reported SoFAS foods were from the groups of beverages, meats, fats and oils, and sweets and desserts. The prevalence of consumption of SoFAS sweets and desserts among adolescents was 50 % higher than that observed for adults and elders. Additionally, the processed meat prevalence of consumption among elders was 50 % lower than the prevalence estimated for adolescents and adults (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prevalence of intake of allowable and SoFAS foods for total sample and adolescents, adults and elders; Brazil, 2008–2009

| Total sample | Adolescents* | Adults† | Elders‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food group§ | Allowable∥ | SoFAS¶ | Allowable | SoFAS | Allowable | SoFAS | Allowable | SoFAS |

| Beverages | 59 | 71 | 46 | 73 | 63 | 72 | 64 | 65 |

| Breads | 61 | 8 | 60 | 6 | 61 | 8 | 58 | 10 |

| Burgers and sandwiches | – | 9 | – | 11 | – | 9 | – | 4 |

| Cereal bars | <0·1 | 1 | 0 | <1 | <0·1 | 1 | 0 | <0·1 |

| Cheeses | <0·1 | 14 | 0 | 9 | <0·1 | 15 | <1 | 18 |

| Eggs | – | 17 | – | 19 | – | 16 | – | 12 |

| Fat- or sugar-added and processed fruits | 2 | <0·1 | 2 | <0·1 | 2 | <0·1 | 2 | 0 |

| Fat- or sugar-added and processed vegetables | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| Fats and oils | 1 | 38 | 1 | 36 | 2 | 39 | 1 | 38 |

| Fish and seafood | 8 | <1 | 7 | <0·1 | 8 | <0·1 | 8 | 0 |

| Fried potatoes | <0·1 | 6 | <0·1 | 6 | <0·1 | 6 | 0 | 4 |

| Legumes | 77 | <1 | 76 | <1 | 78 | <1 | 76 | <0·1 |

| Meat substitutes | <1 | – | <1 | – | <1 | – | <1 | – |

| Meats | 2 | 55 | 1 | 52 | 2 | 56 | 2 | 50 |

| Milk and dairy | 2 | 28 | 1 | 37 | 2 | 26 | 5 | 26 |

| Nuts, seeds, coconut | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1 | <1 | <1 | 1 | <1 |

| Pasta and noodles | 18 | 4 | 19 | 4 | 18 | 3 | 14 | 2 |

| Pizzas | – | 2 | – | 3 | – | 2 | – | 1 |

| Poultry | 7 | 22 | 5 | 23 | 7 | 22 | 6 | 21 |

| Processed meat | <1 | 20 | <0·1 | 21 | <1 | 21 | 0 | 14 |

| Ready-to-eat cereals | 1 | 1 | <1 | 1 | 1 | <1 | 2 | 1 |

| Rice, corn and other cereal dishes | 91 | 10 | 91 | 13 | 91 | 9 | 91 | 10 |

| Sauces, condiments and seasonings | 1 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 1 | 1 | <1 | <0·1 |

| Savoury snacks | 0 | 19 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 18 | <0·1 | 19 |

| Soups | 2 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 15 |

| Starchy vegetables | 16 | 4 | 16 | 3 | 16 | 5 | 16 | 4 |

| Sugar and syrups | <0·1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | <0·1 | 4 | <1 | 6 |

| Sweets and desserts | 1 | 38 | 1 | 51 | 1 | 34 | 1 | 34 |

*Adolescents = 10 to 19 years old.

†Adults = 20 to 64 years old.

‡Elders = 65 years old and older.

§A detailed description of the foods included in each group is presented in Supplementary Materials, Table 1.

∥Allowable foods: providing less than 9·1 % of energy from saturated fat, 1·3 % of energy from trans fat and 13 % of energy from added sugar.

¶SoFAS, high in saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar (see Table 1).

Discussion

Internationally accepted nutrient-based criteria were applied to analyse data obtained in the first nationwide Brazilian IDS, showing that a small number of SoFAS food groups account for a large proportion of the intake of total energy, saturated fat, trans fat, added sugar and total sugar: beverages, sweets and desserts, meats, milk and dairy, and fats and oils. In general, SoFAS foods have an important contribution to food consumption in Brazil, accounting for a large proportion of the intake of total energy, saturated fat and sugar.

SoFAS foods are mostly processed foods and mixed dishes cooked with the addition of fats and/or sugar. For example, filled rolls were classified as SoFAS breads while allowable breads included light white and whole-wheat loaves and rolls. Also, SoFAS milk and dairy included sugar-added flavoured milk/soya/yoghurt/whey-based beverages while allowable milk and dairy included low-fat and skimmed milk.

Adolescents presented greater proportionate intake of SoFAS foods and greater consumption of SoFAS beverages and sweets and desserts than was observed for adults and elders. Andrade et al. ( 23 ) analysed data from a population-based cross-sectional study developed in Rio de Janeiro in the mid-1990s and observed that about a quarter of total energy intake was provided by sodas and highly energy-dense foods, including French fries, chocolate-flavoured milk, cake, cookies, and sweets and desserts. Food habits of Brazilian and US adolescents are comparable, with desserts and sodas contributing most to total energy intake, desserts and pizzas to solid fat intake, and sodas to added sugar intake in US adolescents( 10 ).

The results for the most commonly consumed allowable foods (rice and corn dishes, beverages and legumes) confirm findings of studies that have previously analysed food consumption patterns in Brazil. Using principal components analysis of data from the 2002–2003 Brazilian Household Expenditures Survey, a common dietary pattern based on rice and beans, caffeinated beverages (coffee and tea) and vegetable oils was observed across all regions of Brazil( 24 ). This traditional Brazilian dietary pattern, also identified in other studies( 25 – 27 ), is recognized as healthy and has been associated with favourable weight outcomes in an 18-month randomized trial( 28 ) and with reduced BMI and waist circumference in low-income women living on the periphery of Rio de Janeiro( 29 ).

The high contribution of red meat to energy intake indicates a deleterious aspect of the Brazilian diet; this finding is consistent with recent observations on high consumption of red and processed meat in Brazil( 30 ). Consumption of red meat has been associated with an increased risk of total, CVD and cancer mortality in two US prospective studies( 31 ), with colorectal cancer and with higher levels of oxidative stress biomarkers in European prospective studies( 32 , 33 ). Additionally, the increased consumption of red meat negatively impacts the environment as a result of deforestation for cattle grazing, emission of greenhouse gases, increased water pollution and biodiversity loss( 34 , 35 ).

The results in the present study suggest that the intake of SoFAS in Brazil is excessive and much higher than the range proposed by Maillot and Drewnowski( 36 ), who suggested that a healthy diet can have between 17 and 33 % of energy from SoFAS foods( 37 ). According to the USDA, 35 % of energy intake in the USA is provided by SoFAS foods( 38 ), which is lower than the estimated participation of SoFAS foods in Brazil. However, the criteria to classify SoFAS were more conservative in the present analysis, as the cut-off limit for saturated fat intake was based on 7 % of total energy intake instead of the 10 % used by the USDA; additionally, the ‘level of insignificance’ criteria were applied to specific food groups.

The importance of processed foods in the Brazilian diet has been evidenced. Monteiro et al.( 12 ) showed that ultra-processed foods, including breads, crackers, cookies, sweets, soft drinks, sausages, cheeses, preserved meat, ready-to-eat meals, mayonnaise and sauces, provided 28 % of the energy available in Brazilian households in 2002–2003. Additionally, between 2002–2003 and 2008–2009, possibly as a consequence of the increase in away-from-home food consumption, there has been a reduction in the overall household food availability, except for certain food groups like beverages, bakery products and ready-to-eat meals, which include ultra-processed items( 39 ).

The current study represents the first examination at the individual level with the use of in-depth dietary intake data of the impact of foods with low nutritional quality in the Brazilian diet. The use of individual dietary intake data provides greater ability to create a more detailed analysis of each food and hence a more detailed food categorization system. While the purpose of the broad classification suggested by Monteiro et al.( 40 ) is different and innovative, the criteria proposed in the present study are based on internationally accepted and scientifically defined dietary recommendations, which are linked with a large diet and disease literature( 11 , 22 ). At the same time, it is highly likely that all the ultra-processed high-sugar and fatty foods classified by Monteiro are included as SoFAS. The food classification system used in the present paper provides guidance on foods that must have a limited consumption or must be included in the diet with caution.

Recommended limits of saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar intake are defined for the whole diet and not for single foods( 11 , 22 ). Given the fact that the diet encompasses a variety of foods, and that a considerable proportion of those foods do not contain the restricted components, we elected to allow values which were 30 % over the cut-off points. As pointed out by Roodenburg et al. ( 21 ), this value (30 %) is a starting point and future studies should test its consistency and adequacy to the Brazilian dietary pattern. We did not go a step further as was done in the original study( 21 ) and categorize foods into basic and discretionary as that did not change the categorization in excessive content of saturated fat, trans fat and added sugar.

In order to be properly translated into food and nutrition policies and public health messages, the proposed criteria could be improved; for example, by incorporating favourable aspects of foods like the fibre content, noting that fresh vegetables and fruits are not included in this classification because their consumption should be encouraged. The criteria applied to classify foods in the present work are easily understood and can be universally applied as long as the cultural context and the particular public health scenario are considered.

There is another complexity when it comes to nutrient-related cut-offs. Selected foods such as nuts and seeds would be classified as SoFAS if consumed in excessive amounts; however, they represent important sources of beneficial fats, vitamins, minerals and bioactive components( 41 – 43 ). Such foods are not extensively consumed in Brazil, yet their consumption could favour individuals adopting diets aiming to reduce weight or to improve health. In Brazil the deficiency of vitamin A is still a significant public health problem( 44 ); thus foods like eggs and whole milk, which are important sources of vitamin A, deserve special consideration. Choices of reduced-fat milk and cheeses, lean cuts of meats and cooking methods that require less fat/oil (e.g. steaming, boiling, baking, grilling) could help to reduce the amount of SoFAS in the Brazilian diet. Therefore, food selection must consider the helpful combination of nutrients and other components of the foods, and should be guided by principles involving the amount and frequency of consumption. By clearly defining the foods that should have limited consumption (and those that should be encouraged) in each food group, the proposed food profiling criteria provide helpful guidance on healthy food and nutrition and offer directions for a health-oriented food processing industry.

The current study is not without limitations. First, table sugar consumption was not directly obtained. The amount of sugar in coffee, tea and fruit-based drinks was standardized to 10 % for sugar only and 5 % for sugar plus artificial sweetener consumption. Levy et al.( 45 ) analysed household sugar availability data obtained in the Brazilian 2002–2003 HBS and concluded that 75 % of the energy from sugars came from ‘refined sugars and other caloric sweeteners’ while 25 % came from the sugars added to processed foods. Thus, sugar intake might be based on biased estimates, which is very important given the rising rates of obesity, diabetes and other metabolic disorders in Brazil.

Second, despite intense efforts to obtain reliable data on food composition, for some foods the nutritional composition was estimated based on similar foreign foods or preparations. The latest version of the Brazilian Food Composition Table (TACO) contains information on the nutritional composition of about 600 food items( 18 ), while approximately 2000 foods and preparations were cited in the Brazilian IDS. Finally, although the present analysis is based on only the first day of food records, it is recognized that single 24 h recalls and food records provide decent estimates for population means in extent studies( 46 ).

There are several strengths of the current study as well. The Brazilian IDS food record was evaluated and provides an accurate estimation of energy intake( 47 ). Additionally, the estimates for the intakes of energy and nutrients were comparable with data obtained in similar studies( 37 , 48 , 49 ).

The present study found very high levels of SoFAS foods consumption in Brazil. Interventions aimed at improving overall diet quality are necessary and should take in consideration foods containing excessive saturated fat, trans fat and added sugars, making the consumption of SoFAS foods a major target for Brazilian food and nutrition policies.

Acknowledgements

Source of funding: The Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) supported this work (# 200686/2011-9 – PDEE). Conflicts of interest: All authors declare no conflicts of interest. Authors’ contributions: R.A.P. participated in the study design and conception, data analysis, manuscript conception and writing, and final revision. K.J.D. participated in the data analysis, manuscript conception and writing, and final revision. R.S. participated in the study design and conception, and manuscript critical revision. B.M.P. participated in the data analysis, manuscript conception and writing, and final revision. All authors provided approval for the publication of this paper.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012004892.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Azevedo e Silva G et al. (2011) Chronic non-communicable diseases in Brazil: burden and current challenges. Lancet 377, 1949–1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levy-Costa RB, Sichieri R, Pontes NS et al. (2005) Household food availability in Brazil: distribution and trends (1974–2003). Rev Saude Publica 39, 530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coitinho D, Monteiro CA & Popkin BM (2002) What Brazil is doing to promote healthy diets and active lifestyles. Public Health Nutr 5, 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brasil Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção a Saúde, Coordenação Geral da Política de Alimentação e Nutrição (2006) Guia Alimentar para a População Brasileira: Promovendo a Alimentação Saudável. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; available at http://nutricao.saude.gov.br/guia_conheca.php [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brasil Ministério da Saúde (2011) Consea acompanha programa de redução de sal e gordura em alimentos pela indústria. http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/aplicacoes/noticias/default.cfm?pg=dspDetalheNoticia&id_area=124&CO_NOTICIA=12690 (accessed March 2012).

- 6. Kearney J (2010) Food consumption trends and drivers. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365, 2793–2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reardon T & Berdegué J (2002) The rapid rise of supermarkets in Latin America: challenges and opportunities for development. Dev Policy Rev 20, 371–388. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawkes C (2006) Uneven dietary development: linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Global Health 2, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lignani JB, Sichieri R, Burlandy L et al. (2011) Changes in food consumption among the Programa Bolsa Familia participant families in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 14, 785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reedy J & Krebs-Smith SM (2010) Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 110, 1477–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. US Department of Agriculture (2010) Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: USDA and US DHHS. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM et al. (2010) Increasing consumption of ultra-processed foods and likely impact on human health: evidence from Brazil. Public Health Nutr 14, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lobato JC, Costa AJ & Sichieri R (2009) Food intake and prevalence of obesity in Brazil: an ecological analysis. Public Health Nutr 12, 2209–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levy RB, Claro RM & Monteiro CA (2009) Sugar and total energy content of household food purchases in Brazil. Public Health Nutr 12, 2084–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2011) Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares, 2008–2009: Análise do Consumo Alimentar Pessoal no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sichieri R, Pereira RA, Martins A et al. (2008) Rationale, design, and analysis of combined Brazilian household budget survey and food intake individual data. BMC Public Health 8, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nutrition Coordination Center (2008) Nutrition Data System for Research – NDSR. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Núcleo de Estudos e Pesquisas em Alimentação /Universidade de Campinas (2011) TACO – Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos, 4th ed. Campinas: NEPA/UNICAMP. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2011) Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares, 2008–2009: Tabela de Medidas Referidas para os Alimentos Consumidos no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bezerra IN, Monteiro LS, Araujo MC et al. (2012) Procedures applied to estimate weight and volume measures of selected foods reported in the National Dietary Survey (NDS) 2008–2009. Rev Nutr 25, 645–655. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roodenburg AJ, Popkin BM & Seidell JC (2011) Development of international criteria for a front of package food labelling system: the International Choices Programme. Eur J Clin Nutr 65, 1190–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization (2003) Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series no. 916. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrade RG, Pereira RA & Sichieri R (2003) Food intake in overweight and normal-weight adolescents in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica 19, 1485–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nascimento S, Barbosa FS, Sichieri R et al. (2011) Dietary availability patterns of the Brazilian macro-regions. Nutr J 10, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cunha DB, Sichieri R, de Almeida RM et al. (2011) Factors associated with dietary patterns among low-income adults. Public Health Nutr 14, 1579–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marchioni DM, Latorre MR, Eluf-Neto J et al. (2005) Identification of dietary patterns using factor analysis in an epidemiological study in Sao Paulo. Sao Paulo Med J 123, 124–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sichieri R, Castro JF & Moura AS (2003) Factors associated with dietary patterns in the urban Brazilian population. Cad Saude Publica 19, Suppl. 1, S47–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sichieri R, Moura AS, Genelhu V et al. (2007) An 18-mo randomized trial of a low-glycemic-index diet and weight change in Brazilian women. Am J Clin Nutr 86, 707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cunha DB, de Almeida RM, Sichieri R et al. (2010) Association of dietary patterns with BMI and waist circumference in a low-income neighbourhood in Brazil. Br J Nutr 104, 908–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carvalho AM, Cesar CLG, Fisberg RM et al. (2012) Excessive meat consumption in Brazil: diet quality and environmental impacts. Public Health Nutr (Epublication ahead of print version). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM et al. (2012) Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch Intern Med 172, 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Norat T, Bingham S, Ferrari P et al. (2005) Meat, fish, and colorectal cancer risk: the European Prospective Investigation into cancer and nutrition. J Natl Cancer Inst 97, 906–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Montonen J, Boeing H, Fritsche A et al. (2012) Consumption of red meat and whole-grain bread in relation to biomarkers of obesity, inflammation, glucose metabolism and oxidative stress. Eur J Nutr (Epublication ahead of print version). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Friel S, Dangour AD, Garnett T et al. (2009) Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: food and agriculture. Lancet 374, 2016–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD et al. (2007) Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet 370, 1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maillot M & Drewnowski A (2011) Energy allowances for solid fats and added sugars in nutritionally adequate US diets estimated at 17–33 % by a linear programming model. J Nutr 141, 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Institute of Medicine (2005) Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. US Department of Agriculture (2010) Nutrient Intakes from Food: Mean Amounts Consumed per Individual, by Gender and Age. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2007–2008. Beltsville, MD: USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group; available at http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg [Google Scholar]

- 39. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (2010) Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2008–2009: Avaliação Nutricional da Disponibilidade Domiciliar de Alimentos no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM et al. (2010) A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad Saude Publica 26, 2039–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Falasca M & Casari I (2012) Cancer chemoprevention by nuts: evidence and promises. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 4, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kris-Etherton PM, Hu FB, Ros E et al. (2008) The role of tree nuts and peanuts in the prevention of coronary heart disease: multiple potential mechanisms. J Nutr 138, issue 9, 1746S–1751S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sabate J & Wien M (2010) Nuts, blood lipids and cardiovascular disease. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 19, 131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brasil Ministério da Saúde (2009) Pesquisa Nacional de Demografia e Saúde da Criança e da Mulher – PNDS 2006: Dimensões do Processo Reprodutivo e da Saúde da Criança (National Survey on Demography and Health of Women and Children – PNDS 2006: Dimensions of Reproduction and Child Health). Brasília: Ministério da Saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Levy RB, Claro RM, Bandoni DH et al. (2012) Availability of added sugars in Brazil: distribution, food sources and time trends. Rev Bras Epidemiol 15, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dodd KW, Guenther PM, Freedman LS et al. (2006) Statistical methods for estimating usual intake of nutrients and foods: a review of the theory. J Am Diet Assoc 106, 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lopes TS, Ferrioli E, Pfrimer K et al. (2010) Validation of energy intake estimated by the food record applied in a Brazilian National Individual Dietary Survey by the doubly labeled water method. Presented at II World Congress of Public Health Nutrition, Porto, Portugal, 23–25 September 2010.

- 48. Barquera S, Hernandez-Barrera L, Campos-Nonato I et al. (2009) Energy and nutrient consumption in adults: analysis of the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. Salud Publica Mex 51, Suppl. 4, S562–S573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Whitton C, Nicholson SK, Roberts C et al. (2011) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: UK food consumption and nutrient intakes from the first year of the rolling programme and comparisons with previous surveys. Br J Nutr 106, 1899–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980012004892.

click here to view supplementary material